Polymicrobial infection in cystic fibrosis and future perspectives for improving Mycobacterium abscessus drug discovery

Introduction

Reshaping the monomicrobial perspective

Throughout history, our understanding of medical microbiology has held a monomicrobial bias, influenced by the publication of ‘Koch’s postulate’ by Robert Koch in 18901. This postulate formed the criterion for establishing a causal relationship between a microbe and a disease, including the idea that a pathogen will only cause an infectious disease if it can be isolated from all diseased individuals. Despite setting the foundation for knowledge in microbiology, Koch’s postulate has been criticized for multiple reasons, including the monomicrobial perspective it infers by suggesting that only one microbe will be associated with one disease1. Numerous diseases instead demonstrate a polymicrobial aetiology, including cystic fibrosis (CF)2, whereby microbial ecosystems can develop and influence a therapeutic outcome3,4,5. It is therefore timely to explore infection from a polymicrobial perspective, as would be exhibited in vivo1. In this review, we highlight the importance of reshaping this monomicrobial perspective, including a summary of the current knowledge surrounding the polymicrobial nature of CF. A specific focus will be on how application of this polymicrobial environment could increase the physiological relevance of Mycobacterium abscessus drug screening and discovery, with this species being less studied compared to its CF-associated counterparts.

An introduction to M. abscessus—an emerging opportunistic pathogen

M. abscessus was first recognised in the 1950’s from a patient’s knee abscess, being described as an ‘unusual’ acid-fast bacterium that phenotypically differed to that of the pre-established tubercule bacilli. Being more rapidly growing and dissimilar in its biochemical properties compared to Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the isolate was proposed as the new species Mycobacterium abscessus, owing to the location of its initial isolation6. Such discrepancies therefore placed M. abscessus as a type of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), a group of pathogens consisting of around 200 genetically distinct species that are all outside of the tuberculous realm7.

Our understanding of M. abscessus has progressed significantly since its first isolation, now being accepted as part of a complex of three defined subspecies that are collectively referred to as the Mycobacterium abscessus complex (MABSC). Namely, M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. bolletii, and M. abscessus subsp. massiliense7,8,9 form MABSC, however the taxonomic position of these subspecies has followed assessment over recent years. Initially, M. abscessus was believed to be genomically homogeneous with M. chelonae, and thus it was denoted a subspecies of this pathogen10. In 1992, however, M. abscessus was promoted to species status, because of a degree of genomic and phenotypic diversity between M. chelonae subsp. abscessus and M. chelonae subsp. chelonae. For example, M. chelonae subsp. chelonae was shown to utilise citrate as a carbon source, whereas M. chelonae subsp. abscessus is unable to metabolise citrate11. Later identification of M. massiliense and M. bolletii in 2004 and 2006, respectively, suggested that there are three defined subspecies12,13, however their need to be placed as distinct entities remains under debate. Figure 1 diagrammatically represents the categorisation of these three subspecies, from 1953 through to present day.

Since its first isolation in 1953, the genomics of the species have been scrutinised until three distinct subspecies were later agreed upon6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,121. Figure created on Biorender.com, accessed on 13 April 2023.

Like many of the infectious agents associated with CF, MABSC are ubiquitous microbes, preferentially infecting susceptible patient populations including individuals with CF, bronchiectasis and immunosuppression14,15. It is now considered one of the most common rapidly growing mycobacteria isolated worldwide16, effecting both adult and paediatric patients across the globe17,18. Specifically, it is a common NTM isolated in Australia and Sweden, and is the second and third most common NTM in South Korea and Taiwan, respectively16. In addition, M. abscessus is on the rise in the United Kingdom, with 44% of NTMs isolated in London (England) being identified as rapidly growing mycobacteria in 200816. Despite this global threat, treatment of MABSC remains incredibly challenging, with only a 45.6% cure rate being identified in one study19. There is therefore a huge demand to uncover novel therapeutic agents that can successfully treat MABSC with minimal treatment burden. Despite this need, our current in vitro models are poor predictors of in vivo conditions, therefore significantly compromising drug discovery efforts20,21. The influence of the complex polymicrobial communities on MABSC remains one of the lesser studied interactions, however, this could offer significant potential to improve the physiological relevance of in vitro drug screening and discovery.

Antibiotic resistance in M. abscessus

MABSC has phenomenal intrinsic resistance to antibiotics22. The most widely recognised resistance property within mycobacteria is it’s thick, waxy cell wall, that limits the permeability of antimicrobials into the cell23. This structure consists of a plasma membrane, a mycolic acid, arabinogalactan and peptidoglycan complex (MAPc) and a capsule-like polysaccharide material, forming a complex structure unique to the mycobacteria genus24. The α-alkyl and β-hydroxy mycolic acids form an outer lipid layer that confers its waxy and hydrophobic nature, thus limiting the permeability to hydrophilic compounds. In addition, MAPc acts to structurally support the robustness of the upper myco-membrane, where the capsule-like layer resides24,25. This strength and hydrophobicity contribute to the drug resistance exhibited by Mycobacterial species. Additionally, efflux pumps can reside within this membrane, that can remove antibiotics (such as clarithromycin) from the cell to confer resistance26.

Furthermore, inducible macrolide resistance is commonly observed within MABSC, which is one distinguishing factor that supports the subspeciation of MABSC isolates (Section “An introduction to M. abscessus—an emerging opportunistic pathogen”)7. This is attributed to the presence of erythromycin ribosome methyltransferase 41; a macrolide resistance gene that is typically deleted in M. abscessus subsp. massiliense despite being present within M. abscessus subsp. bolletii and M. abscessus subsp. abscessus27. This gene can be activated by the presence of macrolides (such as clarithromycin), thus categorising this as an inducible resistance mechanism28. The transcriptional regulator WhiB7 is similarly inducible, being induced in the presence of antibiotics such as tetracycline and amikacin29.

Another genetically-mediated macrolide mechanism is the presence of rrl gene mutations, that, in its functional state, encodes the macrolide target 23S rRNA30. Genetic polymorphisms can also induce resistance to a different antibiotic classes, including polymorphisms in the quinolone resistance determining region of Gyrase A that confer fluoroquinolone resistance31. Moreover, M. abscessus expresses the β-lactamase BlaMab; an enzyme capable of hydrolysing the β-lactam ring to induce β-lactam resistance32. Together, these resistance properties make for a very challenging and complex treatment regimen19. Figure 2 provides a schematic representation of these resistance properties in more detail.

Figure created on Biorender.com, accessed on 21 August 2024. ABC adenosine triphosphate-binding cassette, ADP adenosine diphosphate, Arr ADP-ribosylating rifampicin resistance gene, BlaMab Mycobacterium abscessus β-lactamase, eis2 enhanced intracellular survival 2, embB ethambutol resistance gene B, ERDR erythromycin resistance determining region, erm(41) erythromycin ribosome methyltransferase 41, MFS major facilitator superfamily, MmpL Mycobacterial membrane protein Large, RND resistance-nodulation-division, rRNA ribosomal ribonucleic acid, QRDR quinolone resistance determining region.

Polymicrobial infection in cystic fibrosis

The CF lung environment facilitates the colonisation of diverse polymicrobial communities

The pathophysiology of the CF airway creates an environment perfectly suited for M. abscessus colonisation, however NTMs are not the only pathogens associated with CF. Rather, CF infection is polymicrobial, varying between patients2.

CF is characterised by autosomal recessive mutations within the CF conductance regulator (CFTR) gene33,34, resulting in defects to the CFTR ion channel34. This protein functions as a chloride channel and is also a regulatory protein for the epithelial sodium channel, and as such, defective salt transport occurs across epithelial cells when this protein is defective34,35.This dysfunction results in highly viscous sputum, promoting improper mucociliary clearance36,37. In its functional state, this has been elucidated as the primary innate defence mechanism in the airways38, and thus absence of functional mucociliary clearance compromises pathogen defence to facilitate the habitation of microbes. Complex bacterial communities can develop within CF lung, with common species including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, NTMs, Stenotrophomonas maltophila, Aspergillus fumigatus and members of the Burkholderia cepacia complex39,40. These are not the only species to be associated with CF; one study isolated 1837 different taxa in a cohort of 63 CF patients, highlighting the polymicrobial nature of CF bacterial communities. The species comprising these bacterial communities typically vary depending upon the patient, thus highlighting the widespread diversity that is commonly observed within CF. This is particularly true for younger CF patients, with older subjects showing a progressive loss of bacterial diversity over time2.

Interspecies interactions within CF polymicrobial communities

The complexity associated with polymicrobial communities relates to the diverse interspecies interactions that can take place between microorganisms, which can be categorised as either ‘cooperative’41 or ‘antagonistic/competitive’42. The most studied interaction is that between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, with these species being common CF microorganisms (isolated in 73% and 65% of samples, respectively)2. The co-existence of these two species results in changes to a variety of physiological, genetic and biochemical characteristics, including an induction of exploratory motility in P. aeruginosa43, a switch to the small colony variant phenotype in S. aureus44,45 and alterations in nutrient utilisation by the two microbes through nutrient exchange46.

P. aeruginosa has been reported to have a competitive advantage over S. aureus, influenced by the two-component system NtrBC—expression of which is induced in P. aeruginosa in the presence of S. aureus. To investigate this, the activity of the ntrBC promoter in P. aeruginosa was measured by luminescence detection in the presence and absence of S. aureus. At twelve hours post-inoculation, the activity of the ntrBC promoter was 5.1-fold greater in co-culture compared to P. aeruginosa monoculture. When ntrBC was knocked out of P. aeruginosa, S. aureus could outcompete P. aeruginosa—a finding opposite to the competitive advantage shown by the P. aeruginosa wildtype. This therefore indicates that the NtrBC system is capable of moderating the competition between these two species47.

Despite this finding, a mutual antagonism still exists between the two species, which is facilitated by the initial separation of these pathogens in the lung48. Throughout the life of a CF patient, the microbial ecosystem within the respiratory tract will undergo continuous changes, with colonisation of S. aureus and H. influenzae in childhood typically preceding P. aeruginosa colonisation later in life49. S. aureus is thought to establish a bacterial community prior to pseudomonal infection, that will begin secreting P. aeruginosa-inhibiting substances in the presence of glucose48. Glucose is typically elevated within CF sputum, with a mean concentration of 700 µmol/L50,51; therefore suggesting that the composition of CF sputum supports this co-colonisation process. The metabolism of glucose by S. aureus creates organic acid products (such as acetic acid), that have been shown to kill P. aeruginosa48,52. Such mechanism creates a barrier for P. aeruginosa infection surrounding S. aureus cells; a notion termed the ‘S. aureus head-start hypothesis’ owing to the earlier colonisation of S. aureus during childhood. When P. aeruginosa later colonises, it will inhabit an area outside of this inhibitory barrier and begin secreting S. aureus-inhibiting substances to maintain the distance from S. aureus cells48. This mutual antagonism allows co-existence of these species, which is one example of where the interaction could perhaps be described as both antagonistic and cooperative48. Figure 3 provides a diagrammatic representation of the inhibitory molecules associated within this mutually antagonistic interaction; however, it is important to consider the influence of other factors on the frequency of their production. For example, the degree of alginate produced by mucoid P. aeruginosa influences the release of S. aureus-inhibitory molecules (such as siderophores), with alginate overproduction contributing to their reduced release. The mucoid phenotype of P. aeruginosa is therefore thought to indirectly support co-colonisation with S. aureus, highlighting how this mutually antagonistic interaction can also be deemed cooperative53.

The pseudomonal ‘alkyl quinolones’ encompasses 2-heptyl-3-hydroxy-4(1H)-quinolone (or Pseudomonas quinolone signal); 4-hydroxy-2-heptylquinoline-N-oxide (HQNO) and 2-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline (HHQ)47,48,130,131,132,133,134,135,136. Figure created on Biorender.com, accessed on 21 August 2024. AHL N-acylhomoserine lactones, 3-oxo-C12-HSL N-(3-Oxododecanoyl)-L-homoserine lactone, SpA Staphylococcus aureus protein A, STP staphylopine.

Strengthening the notion that S. aureus and P. aeruginosa are both antagonistic and cooperative is the idea that staphylococcal exoproducts (such as staphylopine (StP)) can modulate both types of interaction. StP was found to inhibit P. aeruginosa biofilm formation, thus outlining the competitive nature of this interaction. A cooperative angle was also found to be associated with staphylococcal exoproducts, though, with P. aeruginosa utilising the staphylococcal acetoin and citrate as carbon sources for its growth54. Furthermore, staphylococcal exoproduct S. aureus protein A has an anti-biofilm effect on P. aeruginosa clinical isolates, however the same molecule also prevents phagocytosis of P. aeruginosa by neutrophils55. This complexity emphasises the importance of interrogating the interspecies interactions within the CF lung, however the microbial diversity between each patient will compromise our ability to fully understand these intricacies clinically (Section “The CF lung environment facilitates the colonisation of diverse polymicrobial communities. ”).

Such patient-to-patient differences can be somewhat attributed to the duration of infection, with the inhibitory capacity of P. aeruginosa against S. aureus varying depending on the patient’s duration of infection56. The interactive ability of different species is also different depending on the bacterial load, with Bacillus subtilis effecting P. aeruginosa biofilms to varying degrees depending on inoculation density57. These additional variables demonstrate the diversity between each individual and ultimately emphasises the scale of what remains to be elucidated regarding the interspecies interplay in CF.

The interspecies interactions within CF extend far beyond what has been described between S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. Table 1 provides a more in-depth summary of the interspecies interactions taking place in the CF lung, for species aside from P. aeruginosa and S. aureus.

Intraspecies interactions within CF polymicrobial communities

Adding further complexity is the potential for intraspecies interactions, whereby, unlike those in Section “Interspecies interactions within CF polymicrobial communities.”, microorganisms of the same species can interact with one another. It is well known that genomically diverse isolates of the same species can be associated with CF, being evidenced for both S. aureus58 and P. aeruginosa59,60, thus raising opportunity for intraspecies interactions—although these are generally less studied compared to interspecies alternatives. Thus, little is known about how pathogens of the same species may influence one another, only gaining attention in more recent years. Of interest is the potential for secreted molecules to impact different strains of the same species; for example, R type pyocin-producing strains of P. aeruginosa appear to predominate over non-producers, perhaps due to the pyocins exerting an antimicrobial effect over the non-producing strains61. Similar work has demonstrated how co-culture of different Achromobacter xylosoxidans strains result in an overall increase in bacterial motility; a finding that was also observed for P. aeruginosa62. This work highlights the complexity of the interactions taking place CF microbial populations, raising a requirement for further studies into the intraspecies interactions occurring in vivo.

The relationship between polymicrobial communities and antimicrobials

Polymicrobial communities are thought to lead to the development of microbial ecosystems within the lung, whereby microbial interactions can influence a therapeutic outcome. It is therefore important to consider these populations during antimicrobial discovery, to enable better transferability of outcomes from the laboratory to the clinic.

The relationship between bacterial communities and antimicrobials takes two angles, where either: (1) the antimicrobials influence the polymicrobial community, or (2) the bacterial community impacts antibiotic activity63. There is therefore an extremely complex interplay between these two factors, with them impacting each other in tandem to result in diverse treatment outcomes. The unique microbial composition of each patient is therefore likely to influence antimicrobial activity, perhaps contributing to the persistence of infection despite antibiotic therapy. One example of the former angle relates to P. aeruginosa and Streptococcus constellatus colonisation; tobramycin has been shown to perpetuate antibiotic tolerance in a mixed species biofilm model of these species, with the addition of tobramycin enhancing S. constellatus biofilm formation. This was linked to a tobramycin-induced reduction in P. aeruginosa rhamnolipid production, which would otherwise reduce S. constellatus biofilm viability in the absence of tobramycin64. Considering that tobramycin is a frontline maintenance antibiotic used in CF infections49, this observation is extremely important and highlights how antimicrobial use may perpetuate the persistence of polymicrobial CF infections in vivo.

The reverse can also occur, whereby the bacterial community can affect antibiotic susceptibility. This is similarly important for tobramycin, with P. aeruginosa becoming sensitised to this antibiotic in a mixed biofilm community of S. aureus, Streptococcus sanguinis and Prevotella melaninogenica versus monoculture65. Similarly, the response of M. abscessus biofilms to antibiotics is influenced by the presence of P. aeruginosa; in a dual-species biofilm of these species, ceftazidime showed more effective biofilm inhibition than the single-species alternative of M. abscessus alone66,67. Another example includes the upregulation of the S. aureus tet38, norA and norC genes in the presence of P. aeruginosa, which encode antibiotic pumps and thus confer increased tolerance to tetracycline and ciprofloxacin68.

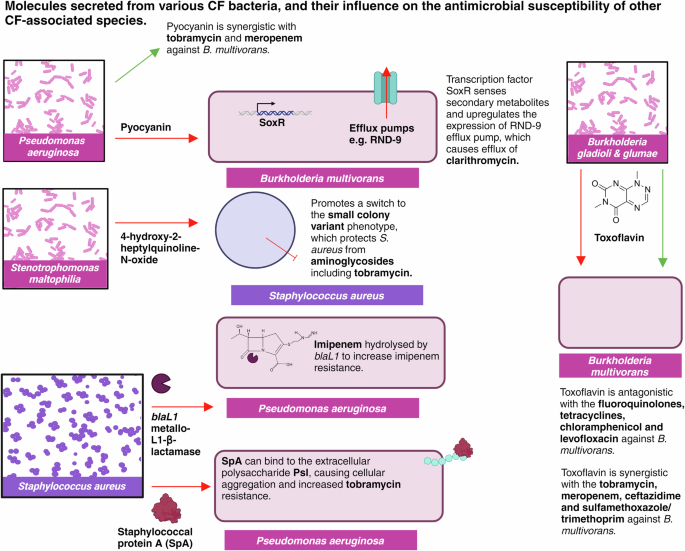

In addition to these interactions, bacterial pathogens can secrete secondary metabolites within the lung, such as the pyocyanin secreted from P. aeruginosa and the toxoflavin produced by Burkholderia gladioli69. These secondary metabolites have the potential to influence treatment outcomes, by inducing efflux systems, modulating oxidative stress responses or effecting redox homeostasis70. Thus, it is important to review the impact of various secondary metabolites on antimicrobial susceptibility, to gauge a better understanding of the influence of polymicrobial communities on treatment success. Considering this complexity during antibiotic screening and discovery may provide significant promise to improve the predictability of drug susceptibility assays, with the addition of pyocyanin and toxoflavin to B. multivorans drug screening increasing the MICs of multiple tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones and chloramphenicol69. Such influence of secondary metabolites may, therefore, be a driving force for the poor clinical success associated with antibiotic treatment; thus, raising the question of how we can tailor treatment approaches to consider these diverse microbial ecosystems. Identification and quantification of 2-heptyl-4(1H)-quinolone, 2-heptyl-3-hydroxy-4(1H)-quinolone and pyocyanin from P. aeruginosa has been achieved in cultures derived from CF sputum samples, for example, using dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction followed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. This advancement raises promise for the use of such systems in clinical settings, enabling a greater understanding of each patient’s unique microbial population and thus helping to inform more efficacious and personalised treatment71. Figure 4 provides a summary of the various molecules secreted from different CF bacteria, and their effects on antimicrobial susceptibility in different species.

Figure created on Biorender.com, accessed 21 August 2024. RND-9, resistance nodulation division 9.

Discussion

Unravelling the complex polymicrobial communities within CF is a major challenge, with the multifaceted nature of the topic posing endless research potential. However, such understanding raises the opportunity to massively improve antimicrobial discovery, with much research highlighting how influential these intricate bacterial communities are on compound susceptibility (Section “The relationship between polymicrobial communities and antimicrobials. ”). Consideration of polymicrobial interactions during drug discovery could offer significant promise to improve physiological relevance, and thus enhance the translation of outcomes from the laboratory to the clinic. However, standardisation of one universal assay is going to be challenging, with the microbial diversity between patients (Section “Polymicrobial infection in cystic fibrosis”) warranting a more personalised approach. We will discuss these challenges in this section, as well appraising the accuracy of the currently used antimicrobial sensitivity assays.

Antimicrobial screening and discovery is typically planktonic and monomicrobial

The standardised guidelines for antimicrobial screening and discovery involve broth microdilution, whereby serial dilutions of a compound are incubated in the presence of a planktonic monoculture in microtiter plates. This setup is monitored using either colony counting72 or optical density readings73, to ascertain how the species responds to different concentrations of compound over time. Resazurin is typically added to each well at endpoint, acting as a viability indicator to determine the minimum antibiotic concentration required to cause bacterial inhibition (minimum inhibitory concentration, MIC). In the presence of viable bacterial cells, reduction of resazurin to resorufin is indicated by a purple-to-pink colour change—thus, the lowest antibiotic concentration to show a purple coloration is identified as the MIC74. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing provides a series of MIC breakpoints, indicative of whether a species is resistant or sensitive to a particular antibiotic following this methodology (https://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints).

Although this process provides a relatively simple indication of how a species may respond to a compound, the lack of physiological relevance associated with this technique poses major challenges when compounds are translated in vivo. As such, the MIC identified in this basic setup is not predictive of the concentrations required in vivo20—especially considering that these assays are typically monomicrobial. Polymicrobial interactions have been shown to have a profound impact on antimicrobial susceptibility, thus raising a demand to develop more sophisticated polymicrobial drug screening models that consider these more resistant phenotypes (Section “The relationship between polymicrobial communities and antimicrobials”)66,67,75. It is undoubtedly a challenge to estimate how a standardised MIC assay will predict treatment success or failure patients on the whole, since each patient’s response to an antibiotic will differ depending on many variable parameters76. However, it is reasonable to suggest that small improvements in physiological relevance, such as those proposed here, will bring these assays one step closer to better representing clinical outcomes.

Challenges to the development of polymicrobial M. abscesses drug screening models

Despite this need to develop polymicrobial drug screening assays, there are major challenges that will compromise the ability to develop one standardised approach. One overwhelming obstacle is the widespread diversity seen between each patient, as described in Section “Polymicrobial infection in cystic fibrosis”. This diversity means that no model will be perfectly representative of each unique case, and so it is perhaps unreasonable to imagine an in vitro assay that is predicative of all in vivo outcomes. Furthermore, each patient is likely to be infected with different MABSC strain(s), and each strain will undoubtedly respond to antibiotics differently. This limitation raises the need for a more personalised approach, whereby each patient is assessed in extensive detail before informing treatment plans; a requirement that so far remains unachievable within medicine. Recent advancements in the field of artificial intelligence raise promise for its application to antimicrobial susceptibility testing77, however, these systems raise inequity challenges as they’re generally only achievable within wealthy countries. Although incredibly promising, the development of such a system would be costly and would perhaps not be attainable on a global scale78.

Another obstacle surrounds the variable growth rates and competition profiles of each species, which is especially important for NTMs that tend to grow slowly compared to other non-mycobacterial bacteria. To determine the efficacy of a compound, bacterial cells must be monitored before and after treatment to ascertain viability—a process that is achieved in monocultures using basic colony counting72 or optical density readings73 (Section “Antimicrobial screening and discovery is typically planktonic and monomicrobial”). However, the variable growth rates of each species will raise challenges regarding the standardisation of bacterial number throughout a polymicrobial assay, meaning that controlled enumeration of cells following treatment may become problematic. It is possible to control the inoculum introduced at the start of an experiment (such as via the use of a standardised number of colony forming units per millimetre (CFU/mL))67, however the different growth rates and competition profiles of each species will compromise the ability to compare the CFU/mL output following treatment. To overcome this, continuous flow models have been developed to enable maintenance of cell number in polymicrobial communities over time, such as between S. aureus, C. albicans and P. aeruginosa. These systems can allow for the maintenance stable communities despite each species outcompeting on another in batch culture79, and are robust and considerably cheaper than existing in vivo infection models. This level of sophistication, however, is yet to be applied to M. abscessus. Application of similar systems to M. abscessus drug screening could allow greater understanding of how antimicrobials behave in a polymicrobial context, as typically exhibited in vivo.

Factors to consider in the development of polymicrobial infection models

Despite being incredibly important when considering physiological relevance, polymicrobial infection isn’t the only factor that must be studied in the development of translational drug discovery models. The CF lung environment extends far beyond this, with another influential host factor including anaerobiosis—induced by the thick mucus plugging in the CF80. Outlining the importance of this is the interplay between S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, with the hypoxic lung environment being thought to facilitate cohabitation of these two species in both mixed species biofilms and planktonic co-culture81. Since drug screening assays typically employ aerobic cultures, the influence of hypoxia is underrepresented and may contribute to inaccuracies during in vitro screening and drug discovery. The impact of hypoxia must therefore inform future studies, adding yet another variable to consider in the development of polymicrobial infection models.

It is also important to consider host cells and bacterial physiology during the development of translational drug screening models. Within the lung, M. abscessus has been shown to adopt a biofilm phenotype, with extracellular matrix-surrounded M. abscessus microcolonies being detected in the intra-alveolar walls of a patient with CF82. Biofilms have been shown to increase the inhibitory concentration of antibiotics by 100-1000x in some species83, and thus a failure to consider this phenotype in vitro would falsely predict antimicrobial tolerance within the body. Furthermore, lung epithelial cells are thought to influence a bacterium’s response to antibiotics, adding an additional layer of complexity. When culturing a dual-species biofilm of M. abscessus and P. aeruginosa on the human epithelial cell line A549, the activity of clarithromycin decreased; likely since this antibiotic can accumulate intracellularly and therefore reduce clarithromycin bioavailability66. It is therefore vital to consider the impact of both host cells and biofilm phenotypes in the development of a translational, polymicrobial drug screening model.

Furthermore, many studies have shown how media choice affects microbial interactions, further highlighting the need to recapitulate the lung environment84,85,86. Since 1997, two lineages of sputum mimetic media have been developed, namely artificial sputum media87,88 and synthetic cystic fibrosis sputum media89—with many compositional adaptations taking place to each recipe over the last few decades90,91,92,93,94,95. Both media types are formulated based on the average concentrations of different nutrients found within sputum, thus offering potential to better represent the metabolism of host infection. An array of bacterial species can grow in this optimised media90,94,96, albeit slightly slower compared to the standard media 7H9 in the case of M. abscessus in artificial CF sputum94. This provides opportunity for researchers to apply such media types to drug discovery, beneficial since this media is based on the average concentrations of sputum metabolites found within a cohort of CF subjects. As such, these media types are theoretically representative of the CF population on average, and therefore they can provide better representation of the clinical situation89. Aside from more recent work65, polymicrobial assays typically make use of standard laboratory media such as tryptone nutrient broth97, and thus we cannot fully estimate the relevance of their results. Future CF polymicrobial studies should consider the application of sputum mimetic media to better represent such communities in vivo, and thus help better predict clinical outcomes.

Conclusions and future directions

Although much is known about interspecies interactions within CF, most of this research surrounds the ‘core’ CF pathogen P. aeruginosa. By considering the interplay between antimicrobials and polymicrobial communities in conjunction with our need for improved M. abscessus treatment, we imply a requirement for further research into the polymicrobial nature of M. abscessus. We demonstrate how application of polymicrobial communities to M. abscessus drug screening offers significant promise to improve the predictability of in vitro assays. Consideration of physiologically relevant media and conditions (such as sputum media, hypoxia, and host cells) would optimise the accuracy of polymicrobial assays even further, by helping raise a phenotype closer to that exhibited in vivo. This change in approach is likely to inform more efficacious antibiotic regimens; a strategy that is beneficial for both antibiotic stewardship and patient outcome. The success of future antibiotic discovery for M. abscessus infection is dependent on the consideration of factors here discussed.

Responses