Post construction infrastructural adaptation of social practices in Dhaka’s under flyover spaces

Introduction

Infrastructure is an expansive term and is used in various ways in academic literature based on applicability. Its conventional definition and usability refer to essential utilities and services like roads, water systems, telecommunications, electricity, and drainage systems, which, when interconnected, create an efficient and functional urban environment1. Physical infrastructure, such as power, irrigation, and transport, is essential for production sectors, while in contrast social infrastructure, including education and health, is crucial for human development and economic growth of a nation2. This research delves into the social and economic implications of flyover viaducts, examining how they impact urban social practices and how strategic management of these spaces can provide value for both the city and the infrastructure itself. When placed in a densely populated mega-city, flyovers can serve as a critical physical element that controls the natural dynamics of the context, potentially impacting the concurrent situation. Such transportation infrastructure, by its imposition, acts akin to a form of colonization—introducing new systems into preexisting urban fabrics. This phenomenon represents an adaptation of contextual social practices due to the presence of flyover infrastructure.

Transportation infrastructure has traditionally been designed with a singular purpose in mind, aimed at serving geopolitical and economic objectives. Often, this approach has led to adverse outcomes, including disrupted landscapes, the defacement of retrofitted constructions, and the loss of cultural and natural heritage3. In contemporary global policy, infrastructure projects have become central, recognized as the primary domain for public investment4, and pivotal for shaping privately financed urbanization5. The complexity of modern infrastructure blurs disciplinary boundaries among landscape architecture, urban design, civil engineering, and architecture, challenging conventional planning and design norms. The significance of strategic planning, efficient decision-making, and the availability of data are underscored as essential for mitigating traffic congestion and facilitating sustainable infrastructure development. It effectively touches many areas of our modern lives6,7.

Throughout history, infrastructural developments such as Roman aqueducts, castle walls, and medieval bridges have not only served their primary functions but have also been integral to social, commercial, and residential life. Examples like the Berlin Hochbahn, Água de Prata Aqueduct, Ponte Di Rialto, Ponte Vecchio, Pont Notre Dame, Viaduct des arts, etc. illustrate this multifaceted utility. In the Global South, similar adaptability is observed with the Flyover Pelangi in Antapani, Indonesia, the Matunga flyover in Mumbai, India, and many more. Prasetyo8 highlights the reclamation of under-flyover spaces in Bandung, Indonesia, for community activities, paralleled by Wang’s9 account of vegetable markets under flyovers in Changchun, China. Urban infrastructure management is a multifaceted challenge influenced by social, economic, and environmental factors. The complexity of managing interlinked systems such as water, energy, transportation, and land use demands a holistic and sustainable approach10,11. The integration of green infrastructure is essential for enhancing urban quality of life12 (12), while community management in developing nations addresses service provision gaps for the urban poor13. These instances of “infrastructural adaptation” of social practice signal a recurring theme of spatial re-purposing, yet the systematic management of such spaces in informal mega-cities remains relatively under-explored.

Historically urban planners, architects, sociologists, and urban thinkers have tried to explain the post-construction infrastructural usage phenomenon and its after-effects in many different forms and illustrations. Rem Koolhaas, in his famous 2002 article entitled “Junk space” stated the aforementioned phenomenon in one of the most useful metaphoric ways possible. To quote him “The product of modernization is not modern architecture but junk space. Junk space is what remains after modernism has run its course. If space junk is the human debris that litters the universe, Junk-space is the residue that humans leave on the planet”. Koolhaas further elaborates by asserting that modern architects and engineers have created more architecture than all the history together. Hence the junk space or such post-construction infrastructural residue spaces are the total of our current tangible infrastructural mass.

The development of highways and roads has been a key driver of economic and social change, with a focus on the benefits to users and the community14. However, this perspective has been criticized for its limited view, with calls for a more holistic approach that considers local innovations and negotiations15 This is particularly relevant in the context of modern urbanism, where the integration of road infrastructure with the city is crucial16. The construction of roads and highways also provides valuable insights into the formation of urban fabric and state17. The famous 1968 Lower Manhattan Expressway conflict between Jane Jacobs and Robert Moses highlighted contrasting visions for urban development: top-down, large-scale infrastructure projects versus preserving existing communities and prioritizing public needs. Jacobs believed that existing buildings and the organic layout of streets were valuable assets to a city, fostering a sense of community and social interaction.18. Koolhaas, in the 1990s, provides an alternative perspective which states that this phenomenon is neither negative nor positive, it is just an inevitable byproduct of urbanization that necessitates coexistence19. In modern times, an infrastructural future is inevitable, especially with the massive scale construction of transportation infrastructures in the current urban conjuncture. Therefore, the need to accommodate the values of local communities in the post-construction infrastructural context demands an understanding of Jacobs’ concepts now more than ever to ensure a human-centered approach to infrastructural planning and adaptation. This research examines one similar case in Dhaka, Bangladesh, where two major infrastructure projects are currently underway: the Dhaka Elevated Expressway and the Dhaka Mass Rapid Transit Lines. Construction is expected to be completed by 2030. Elevated expressway, a total of five MRT Lines, along with the 7 existing flyovers in Dhaka, will total around 68 kilometers in length, with the potential to exceed that figure in the future20.

Arefin21 argues that flyover projects in Dhaka City mainly serve the interests of the capitalist class under neoliberal schemes. Another way of looking at flyover-induced land uses can be found according to Graham’s22article “Elite Avenues”. He discusses the fetishization of elevated highways or flyovers by development and planning elites in megacities of the Global South. The article also notes that flyovers have been sold as transformative icons offering the allure of free and uninterrupted circulation, but they are often more electorally persuasive than cost-effective traffic management schemes for the cities. This is further emphasized by Orski23, who highlights the need for a methodology that is sensitive to social and economic goals, and the importance of new institutions to aid in goal formulation. Cascetta24 proposes a decision-making model for transportation systems that integrates cognitive rationality, stakeholder engagement, and quantitative methods. Wachs25 suggests broadening research programs to include alternative perspectives, such as organizational and personal perspectives, to enhance our understanding of transportation systems. To sum up, an adaptive co-existence of infrastructure and urban life is inevitable as we enter the age of infrastructural transformations. The research narrative emphasizes the process of adaptive approaches to co-existence that balances infrastructure’s economic, and socio-cultural contributions, community life, and local environments.

Infrastructure management is in many cases seen as exclusively a management of the physical body of infrastructure. However, traffic infrastructure or flyovers, elevated walkways, and elevated railway viaducts create additional usable spaces that are part of the infrastructural configuration. Formal management methods of infrastructure are discussed at large as in MCDM or multi-criteria decision-making methods for infrastructure management26. Including under infrastructure land use types in infrastructure management is important, especially in the Global South. Here, due to the absence of formal policies for managing spaces under viaducts, self-management by the communities often becomes the primary approach. Additionally, such places are often under the threat of constant eviction for development works. There is a gap in understanding how these under-viaduct spaces are utilized as an asset rather than a matter of eviction, particularly when it involves unclear ownership of the residual spaces.

Rudneva and Kudryavtsev27 argue that transportation infrastructure constitutes a form of regional capital that imbues areas with both economic and socio-cultural benefits, fostering a synergistic effect upon its implementation. Infrastructural residual spaces are also an asset for the infrastructure. This perspective is crucial, as many countries continue to reorient urban spaces to accommodate the automobile, affecting both formal and informal contexts beneath viaducts of flyovers. Viaducts, defined as a series of arches or columns supporting elevated railways or roads, serve as vital links within the urban fabric, enabling passage over geographical impediments. These infrastructural residual spaces, pivotal to this research, offer the potential for enhancing urban connectivity and economic development but also risk exacerbating the displacement of marginalized communities28. Kabir29 in her Rethinking Overpasses thesis mentions the informality issue as a dominant factor of the everyday life of the under-flyover squatter situated in the same research site (Tejgaon – Nabisco Flyover) as this article.

To achieve such purposes, a range of participatory approaches and adaptive reuse strategies have been explored in the Global South. Brown30 emphasizes the need for transformative shifts in understanding and the use of participatory scenario planning to stimulate forward-looking social learning for adaptive management. Ogu31 underscores the importance of a bottom-up participatory stakeholder partnership approach in urban environmental infrastructure improvement. Mouton32 discusses the material dimensions of ‘smart city’ initiatives in the Philippines, while González33 highlights the potential of participatory design in improving urban spaces in the slums of Caracas, Venezuela. These studies collectively underscore the value of participatory approaches in addressing the unique challenges of infrastructure development and management in the Global South.

Prasetyo highlights how communities promote self-governance, self-regulation, and independence, playing a key role in informal discussions and practices while preserving their self-organized nature. This approach has transformed areas into attractive public spaces, inspiring others to similarly utilize such spaces effectively. Kelbaugh34) refers to this phenomenon as “Everyday Urbanism,” celebrating how indigenous and migrant groups creatively use public spaces, especially in developing countries with growing informal settlements. According to Kelbaugh, this reflects a desire among underserved populations to participate in the city’s economic life. Furthermore, Simone35 emphasizes the need for a detailed examination of how urban life on the fringes adapts through evolving relationships with infrastructure and social dynamics, underscoring its significance for critical urban studies.

Dhaka, the capital city of Bangladesh, is in the process of significantly expanding its physical infrastructure domain with the construction of over 68 kilometers of elevated transportation networks. This development introduces a new layer of complexity to the already dense urban mobility system of a city that accommodates 400,000 migrants annually36, adding to its existing population of 21 million. The emergence of slums, squatter settlements, and an informal economy thrives in the underutilized urban spaces created by such infrastructural projects. As these spaces evolve, they serve as vital areas for the homeless population, merging infrastructure with the daily lives and activities of the city’s inhabitants.

This study concentrates on the post-construction phase of the “Tejgaon-Nabisco Flyover,” also referred to as the Tejgaon Link Road, a key element within Dhaka’s extensive network of seven flyovers. Spanning approximately 1 kilometer, this flyover is notable for housing a squatter settlement beneath its viaduct. This settlement is a hub of socio-economic activities, presenting a unique microcosm between infrastructure and urban life. The Tejgaon-Nabisco Flyover exemplifies the adaptive use of infrastructural spaces, hosting a diverse range of practices that are emblematic of the broader socio-economic dynamics at play within the context of Dhaka’s urban environment. Communities living under flyovers face the burden of paying high service bills for their unique living conditions. Additionally, they live under the constant threat of eviction and are exposed to serious environmental health risks. Although the flyover is owned by the City Corporation, unclear ownership of the residual spaces beneath it allows exploitation by various local authorities with significant power. This research aims to understand the operation and integration of these spaces into the broader urban fabric, focusing on two main questions.

Question 01:

How do communities participate in the production of places by utilizing infrastructural residual spaces?

Question 02:

How do infrastructural residual spaces and their governance adapt to the context of informality in the Global South?

Results & discussion

Finding 01: Infra-element induced microcosm of social practice

Infrastructural elements (flyover column, terminal wall, under-viaduct road, etc.) influence a microcosm of socio-economic practice endemic and adaptive to the local informality, thereby making its nurturing a potential asset for the city.

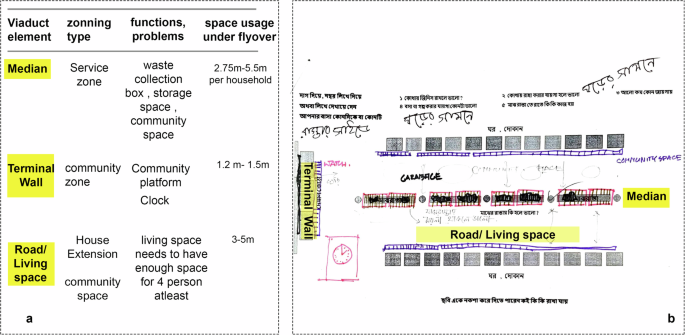

Coming from research question 01, the PAR workshop data analysis reveals how the community utilizes flyover elements—such as the median, median columns, road, and terminal walls—for mixed commercial-residential place-making purposes. Based on an examination of 27 samples, the following key insights emerge:

Median utilization

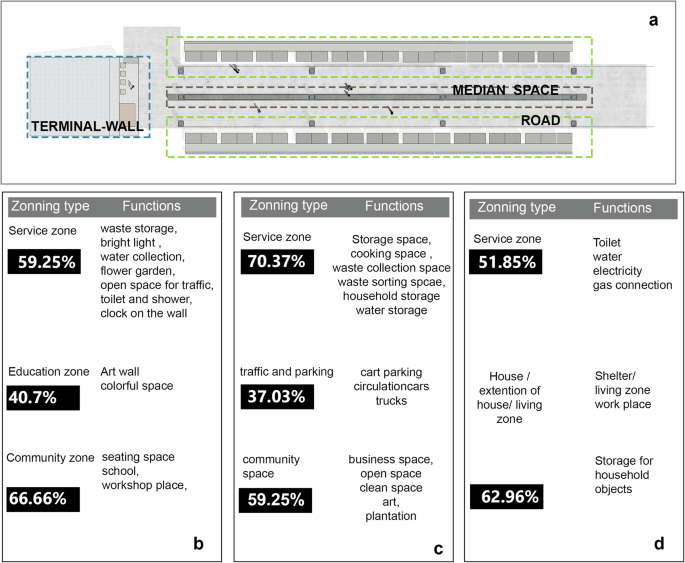

The majority (70%) of inhabitants prefer maintaining the current use of the median for sorting, reselling, and storing waste and household objects, predominantly as a service zone and, secondarily, as a community gathering space as shown in Fig. 1.

This diagram summarizes the usage and zoning ratios of the median, terminal wall, and road based on 27 samples collected during the Participatory Action Research (PAR) workshop. All samples represent residents of the under-flyover squatter community. Panel a shows the site layout having 3 dashed zoning. The dashed lines on the site layout denote the areas: Blue: Terminal wall spaces, Gray: Flyover median spaces, Green: Under-flyover Road spaces converted to habitation and socio-economic activities. Participants can suggest multiple usages for a given under viaduct zone and percentages are provided in the figure according to dashed zoning layout of the site. All the percentage shows a ratio out of 27 samples. Panel b is the information associated with terminal wall, c is the information associated with median of the flyover and panel d is the information associated with the road under the flyover zone.

Road usage

The road beneath the flyover serves dual purposes; one lane facilitates vehicle movement, while the other is adapted for cooking, socializing, and other household activities. Approximately 51.8% express a need for housing services, and 63% indicate a demand for housing extensions, highlighting a significant need for shelter facilities as seen in Fig. 1.

Terminal wall function

Previously hosting an informal school managed by the NGO (Non-Profit Organization) Light of Hope, the terminal wall is favored by 66% of participants as a community space, with 59% advocating for the integration of service facilities alongside educational activities in Fig. 1.

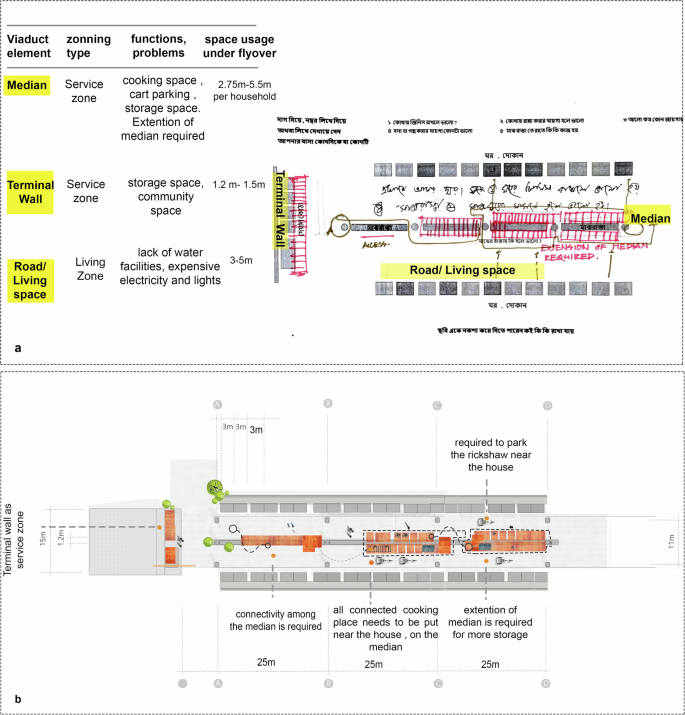

Layout patterns suggested by the participants

27 sets of Participatory Action Research workshop drawings, marked by the direct inhabitants of the under-flyover squatter, not only highlights the current use and problems of the adaptive process, but they are also reflective of the needs and potential image of the under-flyover setup. A comprehensive view of the suggested patterns is presented in the Supplementary Figs. 1–10 with scaled drawings besides the above-mentioned summary of the findings 01.

The squatter community provides an environmental service by cleaning up waste discarded in the area by local industries, markets, and households. They collect and resell the waste and byproducts, creating an informal economy rooted in the local urban context. However, since the polluters do not take responsibility for waste management, the squatter collectors essentially perform the task of cleaning the vicinity and transforming it into an informally operated economic system. This microcosm of informality is crucial to the people, place, and infrastructure, and it relies heavily on the waste management of the Tejgaon industrial area. The colonization of the flyover entity has acted as a catalyst, fueling newer forms of socio-economic practices. This leads us to consider the fact that the squatter community and the under-flyover setup should not be seen as entities to be evicted but rather as assets to be nurtured with specific frameworks.

Finding 02: Autonomous self-governance of infra-residual spaces

In the absence of state-sanctioned or privatized management frameworks, communities autonomously develop self-governed processes to manage infrastructural residual spaces.

The participatory action research data reveals that the current management of these under-viaduct spaces predominantly rests within the realm of self-governance by the inhabitants themselves. This grassroots-led approach entails the inhabitants assuming responsibility for the maintenance, upkeep, and adaptive evolution of the space. Periodically, this self-driven management is complemented by the intermittent support of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs). However, it is noteworthy that the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic witnessed a significant reduction in external aid, rendering the inhabitants more reliant on their self-initiated management strategies.

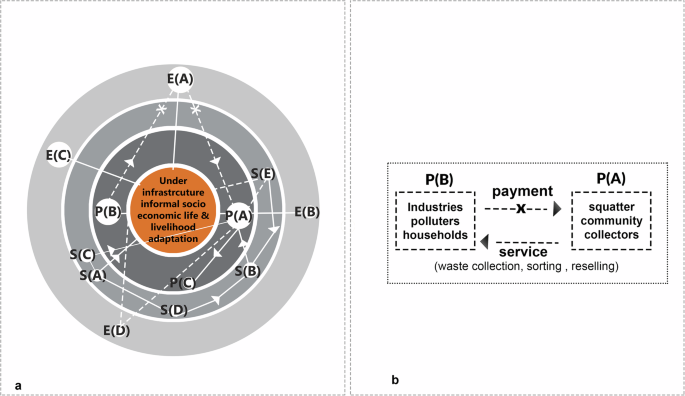

The Stakeholder Onion Diagram is a strategic tool designed to visualize the importance and roles of stakeholders in relation to a system. It typically consists of three or four concentric layers, each representing different groups of stakeholders based on their proximity and relationship to the central issue. As Alexander37 noted, primary stakeholders are those who will operate the system and thus remain close to it. Secondary stakeholders are users who will not operate the system but will consume its output. They are managers who rarely consume the system’s output directly but utilize the information for planning and strategic control. Table 1 illustrates the role and category of the stakeholders.

Examining the onion diagram in Fig. 2a, we observe that organizations of policymakers (S(A)), categorized at the secondary onion level or as secondary stakeholders, are largely disconnected from the systems operating within the under-flyover squatter community and its closest actors, P(A) the squatter community, and P(B) the local industries. Services such as electricity are provided at a higher cost by local area-based political organizations (S(C)), yet the locals (P(A)) are far from being the primary beneficiaries. A significant connection impacting the economic dimensions of the system exists between P(A) and P(B). The reciprocal nature of this system highlights that community squatters offer a rudimentary waste management service to local polluters free of charge (illustrated on Fig. 2b). This system, autonomously developed among the squatter inhabitants, ensures the continuity of sustainable management, environmental cleanup and survival of the locals. This cycle has persisted for several years, predating even the construction of the flyover. The presence of flyover infrastructure enhances the setup, intertwining people and places, and offers a foundation with its infrastructural elements to host multitude of socio-economic practice. This evidences that, in the absence of formal policies governing spaces under flyovers or infrastructural residual areas, contextual socio-economic systems emerge, adapted by the communities themselves.

Panel a depicts a stakeholder “onion diagram” in current context with the under-flyover squatter community at the core, showing the level of connection among primary, secondary and external stakeholders. Stakeholders closer to the center are more involved in environmental management, while those towards the outer layers are less involved. Orange color at the center depicts core site context and living within infrastructure/infrastructural adaptation as the main issue of the research. The second layer of darker gray band shows the Primary stakeholders. The third layer with lighter gray bands depicts secondary stakeholders and outer band gray depicts external stakeholders on the fourth layer. Dashed line shows an indirect/weak connection among stakeholders while unbroken lines show direct/strong connection among stakeholders in the system. In both panels the direction of exchange is shown with triangular arrows while cross shapes denote no exchange of information or resource. Panel b illustrates the symbiotic relationship between the flyover infrastructure, local industries and the squatter community. The community transforms the space for habitation and commerce, potentially managing wastes from the polluters (collection, sorting, resale) while generating income from under-flyover activities. This relationship of Infrastructural elements and self-management by the occupying community is identified as an asset for the environment. Table 1 refers to the list of stakeholders associated with the current system.

Discussions

This study provides a few key issues regarding the management and utilization of infrastructural residual spaces, emphasizing their inevitable role in urban development in the future of global south cities.

First, eventually, spaces generated by physical infrastructure (having social, commercial, and political value) cannot be overlooked for development and it is an organic phenomenon. The research explored a specific context. Further studies could analyze under-viaduct spaces in different geographic locations, climates, and socio-economic settings. How do these factors influence spatial utilization, management strategies, and community needs? Comparative case studies of successful under-viaduct projects across the globe could provide valuable insights.

Secondly, effective management of these spaces, be it privatized, state-controlled, or self-managed —necessitates collaboration with local councils, communities, and area-based organizations. This partnership is essential for providing sustainable land use guidance that transforms these people and places into valuable assets rather than liabilities subject to eviction. When organizational support is missing, communities depend on autonomous self-organization. Future research could delve deeper into effective collaboration models. What are the best practices for engaging local councils, communities, and area-based organizations? Could digital platforms facilitate communication and co-creation processes? Evaluating existing collaborative models can inform the development of successful partnerships for future projects.

Thirdly, establishing a transparent facilities and service rent structure based on a cost-to-income ratio, rather than market willingness to pay, is essential for equitable access to both public and commercial spaces beneath viaducts, including provisions for monitored public use. The research highlights the need for equitable access to under-viaduct spaces. Further research could explore innovative rent structures that consider affordability and social impact alongside cost recovery. Can a blended approach that combines market rents and subsidized spaces promote social inclusion and diverse uses?

Are existing policies flexible enough to accommodate the diverse and evolving needs of urban negative spaces? Are infrastructural residual spaces a product or a feature? If a feature, how do we appropriate the value of it? As urban centers continue to evolve around efficient mobility systems, it becomes crucial to consider the socio-economic and cultural phenomena arising in conjunction with such infrastructure. This research underscores the need for development proposals to consider the multifaceted values of users and communities, ensuring integration with the urban fabric. Moving forward, exploring under-viaduct spatial design, community self-management, and resource utilization will provide valuable insights for formal and informal urban growth strategies, enhancing post-infrastructure adaptation efforts. Future research could analyze existing planning regulations and legal frameworks governing under-viaduct spaces. This research can inform the development of policies that promote sustainable and adaptive use of under-viaduct or infra-residual spaces.

Methods

Urban context analysis: site forces and stakeholders

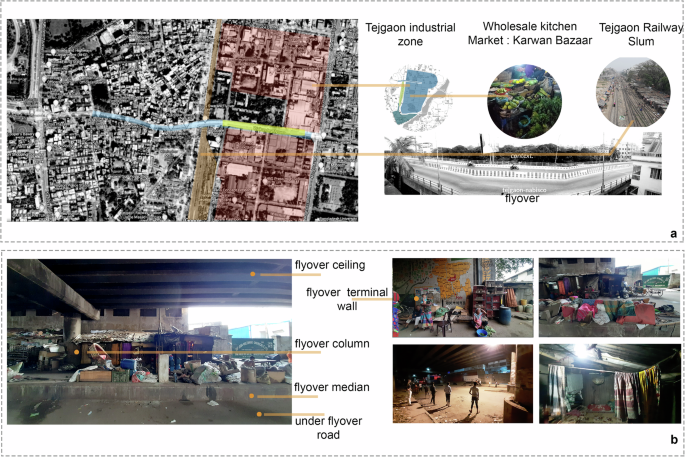

The Tejgaon-Nabisco Flyover, also known as the Tejgaon Link Road, is a 1.114 km structure inaugurated in 2010 to connect The Tejgaon Industrial Zone with Dhaka’s main Mirpur arterial road, crossing over the Tejgaon railway lines. This area is home to a significant population of urban poor and lower-middle-income communities. Initially approved at a cost of Taka 114 crore (approximately 11 million USD) by the National Economic Council in 2007, the flyover surrounds an industrial and commercial landscape, juxtaposed with railway slums and Karwan Bazaar kitchen market atop the Tejgaon industrial zone (As shown in the Fig. 3). Historically, since the 1970s and well before the flyover’s construction, slums have occupied this area. These communities have adapted to the under-viaduct spaces since 2010. Industrial activities dominate the Tejgaon area, significantly impacting the environment through non-organic waste production and contributing to health hazards due to inadequate waste management. Despite daily road and drain cleaning efforts by Dhaka city corporation, policy implementation gaps, insufficient waste disposal infrastructure, and limited recycling capabilities exacerbate the challenge of managing industrial byproduct waste. Dhaka faces a growing waste management crisis, with daily waste generation projected to reach 47,064 tons by 202538. Dhaka recovers only 37% of its waste, leading to widespread environmental degradation. The Tejgaon industrial area is a major contributor to this issue, underscoring the urgent need for enhanced waste collection and recycling efforts.

Panel a at the top depicts the site’s condition and three major surrounding contextual forces. The flyover is strategically located near Tejgaon industrial zone, Karwan Bazaar, the largest kitchen market in Dhaka, and Tejgaon railway lines. Pink is shown as an Industrial zone, Yellow as research site, blue as the full span of the flyover while gray marks the railway slum. Panel b at the bottom showcases the living conditions within the squatter settlement situated under the flyover and highlights the flyover’s structural elements (ceiling, terminal wall, column, median, roads) supporting the livelihood activities of the squatter community. The aerial map was collected from Wikimapia and edited to color code the adjacent zones by the authors.

Our research focuses on the squatter zone under the flyover, which houses 33 housing units and serves as an active living area. In analyzing this residential zone, we’ve identified various stakeholders based on their roles and proximity to the site. Primary stakeholders, designated as P(A), include the squatter community living and operating within close vicinity of the area. Industries, householders, and polluters in the area are categorized as P(B). Additionally, businessmen who profit from purchasing waste and byproducts from the squatters are classified as P(C) in Table 1. The stakeholders’ chart is essential to understand Research Question 01. It shows how primary stakeholders create economic activities using infrastructure. We will visually represent these relationships in the Findings 02 section with an “onion diagram” of stakeholders, highlighting how place making, economy, and infrastructure are interconnected.

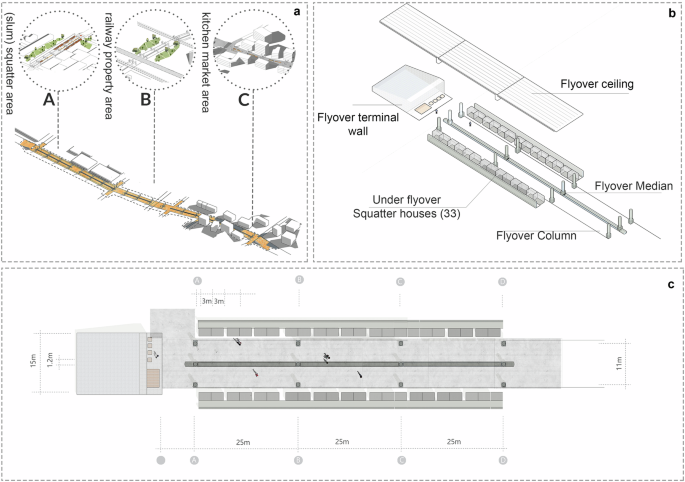

Participatory action research (PAR) workshop

Our study focuses on the Tejgaon Nabisco under-flyover squatter community. To effectively understand the interaction between community and physical infrastructure, we employed participatory action research as our methodology. This approach facilitated the collection of comprehensive data, encompassing both visual representations (drawings) and demographic information, through the conduct of two workshops. These efforts provided insights into the spatial and social relationships forged between the community and the infrastructural elements, revealing the operational dynamics of these urban spaces. As seen from the Fig. 4, participants were selected from among the occupants of 33 houses situated beneath the Tejgaon Nabisco Flyover. This focused sampling aimed to capture insights from individuals directly engaging with and adapting to the unique conditions presented by living under the flyover, alongside the prevailing site dynamics. A total of 27 sample datasets were collected out of these 33 household inhabitants. Participatory Action Research (PAR) was chosen for this study to enable a longer and more meaningful interaction with participants than other methods. PAR methodologies also engage residents in revealing the three-dimensional place making qualities associated with infrastructural adaptation on a 2D perspective through mapping respective zoning patterns. Participants actively considered their surroundings and the flyover’s infrastructure elements, transforming them into place making tools and incorporating existing forms of infra-residual land use. This method of drawing and providing information involved the squatter dwellers in a broader and deeper scope. Photographs contain no identifiable faces of individuals, and all images are of public spaces on a thoroughfare road under the Tejgaon Nabisco Flyover. Necessary permissions were obtained while photographing visible public spaces and adapted livelihood patterns associated to it.

The Tejgaon-Nabisco flyover is divided into three distinct zones, with our research specifically focusing on Site A, identified as the squatter community zone. This area is actively occupied and utilized for housing beneath the flyover. Panel a shows the full layout of the 1.14 km long under flyover land-uses. Figure panel b highlights the setup under the flyover site A, squatter zone (flyover terminal wall, flyover ceiling, flyover median, squatter houses, flyover column, under viaduct roads etc) and the composition of the squatter community in an axonometric diagram. Panel c presents a scaled layout of site A, intended to serve as the basis for the participatory action research diagram.

Aim and objectives

The workshops aim to engage the under-flyover community, equipping them with tools to articulate their experiences and interactions with under-flyover spaces. Aim of the workshops are as follows-

As part of this study, a detailed map of Site A, (Fig. 4b) was created using dimensional surveys and AutoCAD. This map serves as the foundation for participatory action research workshops, enabling squatter inhabitants to engage in the usage identification of their living spaces. The data analysis is done by collecting land use patterns through scaled drawings, highlighting the community’s integration with the flyover’s infrastructure. Table 2 highlights the aim and objective of the setup clarifying the questions asked in the process.

The questionnaire design for our participatory action research (PAR) workshops was crafted to engage the community living under the Tejgaon Nabisco Flyover, consisting of 33 households. Figure 5 panels reflect the under-flyover squatter setup that has been presented in the 4b site layout. A total of 27 samples were collected from these 33 households through participatory action research workshops (see Fig. 5e–g). The objective was to gather detailed demographic information, understand living conditions, and map out the spatial utilization under the flyover. The questionnaire was divided into two main sections:

a Provides a view of the under-flyover squatter: Median use as storages, squatter house composition under the flyover. b Shows Terminal wall used as community platform and art wall as an under-flyover school “The wall attic”. c Gives a look at the waste and by product collection at median by the community waste collector and sellers. d Shows Participatory Action Research Workshop organized on the road and median of the under-flyover space by the authors.

Demographic and Living Conditions Survey: This section aimed to collect basic demographic data such as gender, age, family size, the occupation of the primary earner, monthly household income, and the extent of public space utilization for livelihood activities. It also sought insights into the types of waste products collected in the area, aiming to understand the environmental impact of the squatter settlements.

Spatial Utilization and Zoning Mapping: Participants were asked to identify and illustrate the current patterns of usages under the viaduct and how the infrastructure elements (terminal wall, median, road, ceiling) support or hinder their livelihoods. This part of the questionnaire facilitated a hands-on approach, allowing participants to draw their living and working zones directly on-site layouts provided by the researchers (datasets 02). These drawings were later digitized and scaled using AutoCAD for a precise analysis of land use patterns (datasets 03).All the graphical data sets (data set 02, 03) try to depict the conditions seen in Fig. 5 photographs.

The workshops produced three types of datasets: demographic information, hand-drawn maps of land use (Datasets 02), and AutoCAD representations of these maps (Datasets 03), offering a comprehensive view of the community’s adaptation to under-viaduct spaces following the Table 3 conventions. This approach was tailored to the community’s ability to express their spatial experiences and aspirations, blending quantitative data with qualitative insights into their daily lives and challenges.

Workshop data analysis

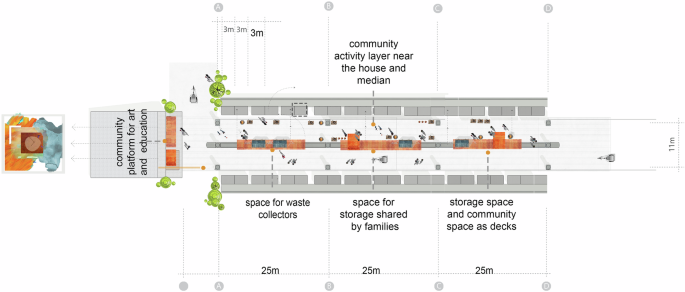

Sample 01

Within the scope of Workshop 02, which collected output from 27 participants, the accounts of Zahid—a 25-year-old male cart puller—provides insightful observations on the adaptive use of under flyover spaces in urban settings. His contributions, documented through drawings, reveal the median platform’s dual function as both a communal gathering space and a site for waste collection and storage, illustrating the community’s innovative re-purposing of infrastructural elements for essential services.

Zahid states that the terminal wall also serves multiple purposes: continuing its role as a canvas for community art while incorporating a new design feature, including a wall clock to assist in synchronizing communal activities. This observation not only retains the wall’s cultural significance but also enhances its utility for the community’s daily routines. Median serves primarily as a service zone while the terminal wall is community space.

Despite these adaptive strategies, Zahid and his fellow residents express concerns over the spatial constraints for family residences and the lack of adequate service facilities and housing extensions on the road under flyover. He identifies the exterior porches of houses on the road as potential areas for expansion, suggesting their use as extended communal spaces to mitigate the shortage of living space. Zahid’s feedback on the current usage of the flyover Median, column, road is illustrated in Fig. 6. His perspectives highlight the necessity for urban designs that accommodate and enhance the lived experiences of marginalized communities, advocating for a more inclusive approach to infrastructural development.

Panel a of the figure displays the usage and zoning of three infrastructure elements as identified by Participant 01, Zahid (Sample 01). Panel b features a drawing by Zahid, illustrating the zoning and usage patterns around the median, terminal wall, and road beneath the flyover. This is labeled as data set 02, sample 01. The right side follows the codes and instructions as per Table 3 above. Participants were requested to draw or identify the current use of median, terminal wall and road under the flyover. Yellow highlights in both panels depict the location of the infrastructural elements on the participant drawing.

It can be noted that all 27 samples in Dataset 02 adhere to the same format and workshop instructions as outlined in Table 3. Each sample in Dataset 02 (see Figs. 6, 8a, and 9a) showcases the existing zoning types of flyover elements (terminal wall, column, road). After collecting information from Dataset 02, each sample was redrawn in AutoCAD to create a scaled version that reflects the informal setups as per each participant’s view (labeled as dataset 3). For instance, Fig. 7 presents the scaled drawing based on Fig. 6.

This scaled AutoCAD drawing is based on the layout created by Participant 01, Zahid (Sample 01), in Fig. 6. It represents Zahid’s interpretation of how the squatter community currently adapts to the infrastructure, highlighting the zoning and active use of infrastructural elements. The drawing, labeled as Dataset 03, Sample 01, denotes the locations of the storage zone with orange-colored outlines, the cooking zone with a gray outline, and household objects in the median with blue-colored outlines. The community platform area within the under-flyover space is also outlined in orange. Dashed lines mark the connectivity inside the layout zones.

In Fig. 7, the suggestions from Zahid (sample 01) regarding the use of the under-flyover area are depicted with specific symbols and legends, as provided in Fig. 6. The zoning layout in Fig. 7 emphasizes the prevalent use of the median in platform symbols, indicating medians primary use for storing collected wastes, byproducts, and household objects. Photographic evidence of this drawing can also be seen in Fig. 5.

Like Dataset 02, Dataset 03 includes 27 scaled drawings gathered from participants across 33 squatter households under the flyover. These drawings were analyzed to produce the findings presented in the results chapter (see Fig. 1). Two more samples (Sample 02, 03) are discussed as an example.

Sample 02

Anguri, a 30-year-old female and a factory worker, highlights the dual use of the median and road under the flyover; she describes these spaces as serving both as living areas and rickshaw and vehicle routes, as shown in Fig. 8. The median is also utilized for parking rickshaws owned by some residents of the squatter community beneath the flyover. Anguri suggests extending the houses and increasing their height as development strategies for the squatter area. Similar to Zahid (Sample 01), Anguri identifies the median as a service zone and the flyover’s terminal wall as both a community platform and an art wall.

Panel a represents Anguri’s view on the squatter community’s current adaptation to infrastructure and its problems. These sets illustrate the zoning and active utilization of infrastructural elements by the community, focusing mainly on vehicular connections and waste collection zones. Yellow highlight depicts the location of the infrastructural elements on the participant drawing. Panel b shows a scaled AutoCAD plot of the layout from Panel a. Dashed lines mark the connectivity inside the layout zones. The following legends are used in the diagram: the storage zone is outlined in orange, the cooking zone is outlined in gray, and household objects in the median are outlined in blue. Additionally, a truck outline indicates the location of the industrial area vehicle movement route.

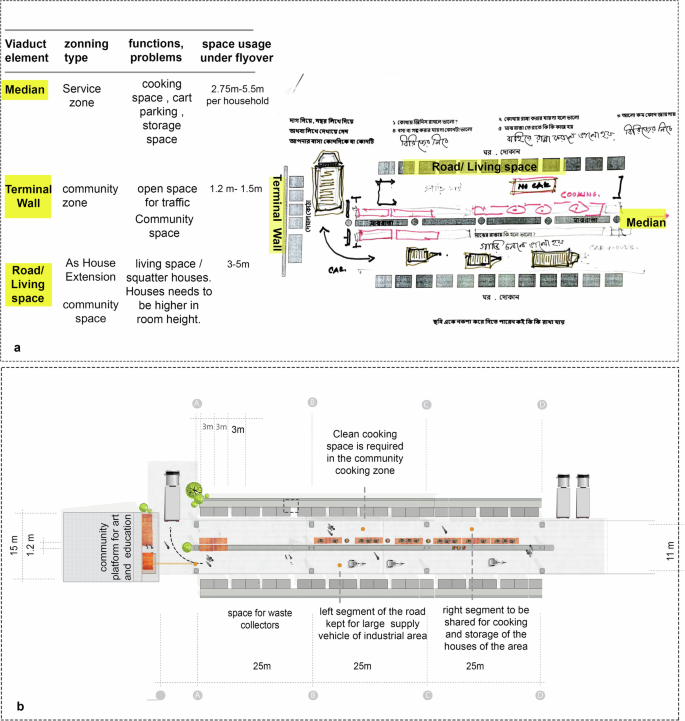

Sample 03

Sample 03 features Bacchu Miah, a 60-year-old rickshaw puller, who views the terminal wall primarily as a service zone rather than a community platform. Contrary to Zahid (Sample 01), Bacchu Miah envisions the median more as a communal cooking area than a storage space. He adds that both the median and terminal wall are fully utilized as service zones. Bacchu Miah sees the road beneath the flyover as a potential living space and advocates for its expansion to accommodate additional housing facilities (see Fig. 9). He also points out that the service costs, such as electricity, are significantly higher than in formal households, and highlights a critical shortage of potable water and sanitation services under the flyover. As depicted in Fig. 9, Bacchu Miah shows his suggestions through drawings and written observations. A similar methodology as sample 01, was applied to translate Dataset 02 Sample 03 into a scaled AutoCAD drawing for Dataset 03 Sample 03.

Panel a depicts Bacchu Miah’s perspective on the squatter community’s current adaptation to infrastructure and its problems. These sets illustrate the zoning and active utilization of infrastructural elements by the community as he emphasizes the under-flyover land use for storage facilities. Yellow highlight depicts the location of the infrastructural elements on the participant drawing. Panel b reflects the scaled AutoCAD plot of the above a layout. The following legends are used in the diagram: the storage zone is outlined in orange, the cooking zone is outlined in gray, and household objects in the median are outlined in blue. Additionally, a rickshaw outline indicates the parking zone and movement route of the rickshaw owners of the squatter.

Our first research question focused on how communities engage in place-making by utilizing spaces left over by infrastructure. The analysis of 27 pairs of Datasets 02 and 03 reveals the layout patterns, usage typologies as observed and drawn by 27 out of 33 households in the squatter community under the flyover. (see the Supplementary Figs. 1–10) The primary insight from these datasets pertains to the predominant zoning types as perceived by the inhabitants. While each participant proposed their unique development strategies, the scope of this research prioritizes the current usage of flyover elements and their role in fostering connections among people, places, and social practices. A summarized finding is presented in the discussion chapter. Consequently, future research should investigate the role of urban planning authorities and the integration of infrastructural spaces into the broader urban ecosystem, addressing critical questions of governance, access, and sustainability.

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before participating in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The participatory action research data from Dataset 02 provided in the manuscript were produced by the participants themselves, with informed consent and full knowledge of the research methodology. “All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before participating in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The participatory action research data from Dataset 02 provided in the manuscript were produced by the participants themselves, with informed consent and full knowledge of the research methodology. The research, ‘Post Construction Infrastructural Adaptation of Social Practices in Dhaka’s Under Flyover Spaces,’ was approved by the ethics committee and thesis review board of the Global Environmental Architecture Lab, Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies, Kyoto University, Japan.

Responses