Potent bivalent nanobody constructs that protect against the SARS-CoV-2 XBB variant

Introduction

Since the emergence of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Omicron variant in 2021, its high mutation rate and transmissibility have been a major clinical concern1,2. The SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein is an immunodominant surface glycoprotein that contains the receptor binding domain (RBD). The RBD binds to the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) upon infection and is a primary target of neutralizing antibodies isolated from sera of infected or vaccinated individuals3. Mutations in the RBD may therefore result in increased immune evasion4,5. For instance, the Omicron variants of the XBB and BA.2.86/JN.1 lineages possess amino acid substitutions in the RBD protein that enhance evasion of pre-Omicron neutralizing antibodies6.

Conventional monoclonal antibodies serve as an important class of therapeutics for various diseases and viral infections. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, antibody treatments have been studied and several were approved in the United States for emergency usage7,8,9. The newly emerging Omicron variants, however, have been found to be resistant to existing monoclonal antibodies6,10,11. Two antibody treatments approved in the United States, Evusheld (AstraZeneca) and bebtelovimab (Eli Lily) were ineffective against emerging variants such as BJ.1, XBB, CH.1.1, and BQ.1.112. The United States Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) rescinded their approval for bebtelovimab in November of 2022 and Evusheld in January of 202313,14. The emergency use authorization (EUA) by the U.S. FDA for another antibody, sotrovimab (GSK), was rescinded in April of 2022 due to increases in the proportion of cases caused by the BA.2 subvariant15. Pemivibart was newly approved in March of 2024 by the U.S. FDA but showed greatly reduced neutralization activity against JN.1 sublineage variants like KP.3.1.116,17,18. All other antibody therapeutic treatments given EUA showed limited activity against earlier Omicron variants such as BA.1, BA.5, or BA.2.75.2 and are no longer approved for use19.

In addition to conventional monoclonal antibodies, single-domain antibodies, or nanobodies, have also gained attention as alternative therapeutics targeting SARS-CoV-2. Nanobodies are heavy chain-only antibody fragments that are derived from the variable domain of camelid antibodies20. Nanobodies possess several desirable properties over traditional antibodies such as high thermal and chemical stability, modularity, and ease of production21,22,23.

Due to the immune evasive characteristics of the newly emerging SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants, nanobody-based therapeutics are being designed to combat recent Omicron variants. Modhiran et al. constructed a human Fc-fused nanobody, W25, derived from alpacas immunized with ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain and saw protection against the Beta and BA.1 variants as well as sub-nanomolar binding affinity to XBB.1.5 S24. High affinity nanobodies are more likely to outcompete the ACE2 receptor and remain bound to the S protein, inhibiting the interaction between the spike and ACE2. Yao et al. engineered a trivalent construct with nanobodies acquired from screening a phage display library against BA.1 and demonstrated protection against BA.1.1, BA.2.3, and BA.5 in mice as well as neutralization against XBB.1.525. A bispecific nanobody dimer constructed by Ma et al. protected hamsters from a challenge with BA.1 with no viral titers detected in the lungs and trachea, and a RBD-binding interface analysis suggested that a Y29G mutation could allow the nanobody dimer to potently neutralize BA.2.75, BA.2.3.20, and XBB variants26. An Fc-based tetravalent nanobody derived from an immunized alpaca by Yang et al. showed micromolar binding to XBB RBD27. Solodkov et al. conducted sequential screenings of llama-derived phage libraries against various strains of SARS-CoV-2 and constructed an Fc-fused nanobody that had neutralization activity against the XBB lineage28. Wang et al. engineered nanobodies that showed reduced lung viral titers against XBB.1.1629. Dong et al. 30 used alpaca immunization followed by iterative MACS-sorting and FACS-sorting to identify a potent nanobody which upon intranasal administration in Syrian hamsters, effectively prevented respiratory infection and transmission of the XBB.1.5 subvariant. Many of these identified nanobodies, however, were derived from immunized camelids24,31,32,33,34,35,36. Immunization of camelids is a low throughput and expensive approach, which sets a high barrier for developing nanobody-based therapeutics23. Using in vitro antibody discovery and a surface display method such as yeast surface display or phage display could help overcome these challenges.

In this study, we developed three Fc-fused nanobody constructs, XNb 4.13-Fc, XNb 4.14-Fc, and XNb 4.15-Fc, through the screening of a yeast surface display nanobody library against XBB RBD. We show that these nanobody constructs bind with sub-nanomolar affinity to the XBB S protein. Two of the nanobody constructs, XNb 4.13-Fc and XNb 4.14-Fc demonstrated neutralizing activity against XBB in vitro and reduced viral lung titers in mice challenged with XBB.

Results

Identification of nanobodies targeting the XBB spike protein

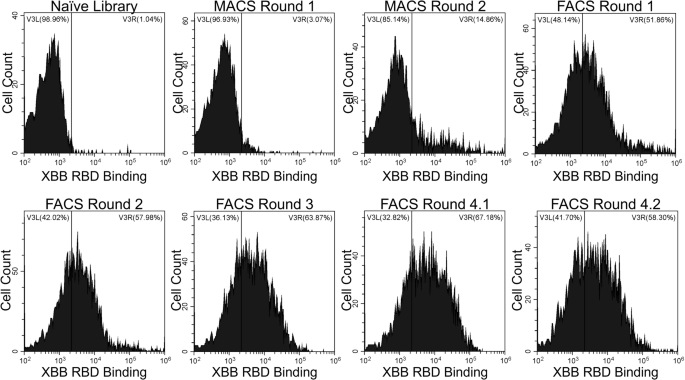

To identify nanobodies that target the spike protein of the XBB SARS-CoV-2 variant, we screened a synthetic yeast surface display nanobody library against recombinant XBB RBD37. These screens involved two rounds of MACS against XBB RBD immobilized on magnetic beads and then four rounds of FACS against decreasing concentrations of XBB RBD. During FACS Round 4, two populations of yeast expressing RBD-binding nanobodies were sorted (indicated as 4.1 and 4.2) to ensure selection of a variety of unique nanobody mutants. After each sort, yeast cells were labeled with XBB RBD (Fig. 1) to evaluate binding. Throughout our rounds of screening, we observed an enrichment of binding to XBB RBD.

Yeast cells from the naïve nanobody library or enriched libraries after magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS) or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) screens were labeled with 30 nM XBB, and the extent of binding was evaluated with flow cytometry. Fluorescence signal corresponding to XBB RBD binding to yeast-displayed nanobodies is shown on the X-axis. Binding to XBB RBD above the level of the nanobody library appears on the right side of the vertical gate.

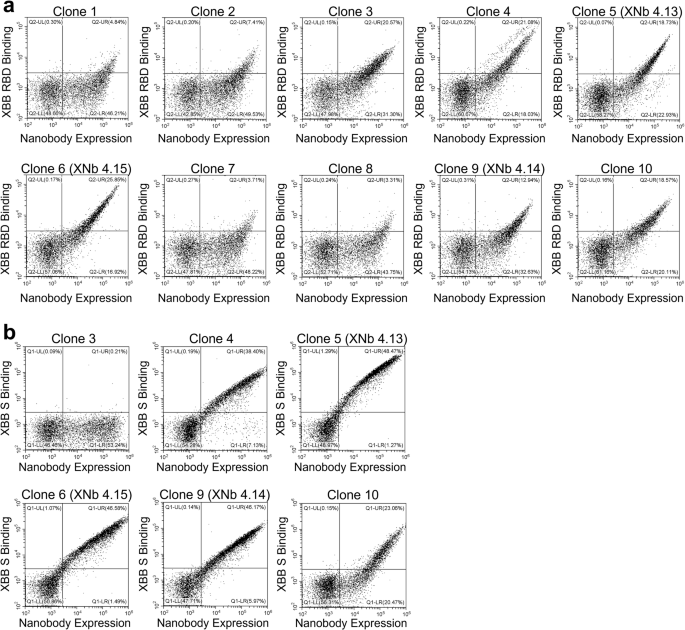

From the enriched libraries resulting from FACS Round 4.1 and 4.2 sorts, 12 nanobodies were randomly selected and sequenced. Of the 24 nanobodies selected, ten had unique sequences (Table 1). Flow cytometric binding analysis was performed to assess binding of these ten yeast-displayed nanobodies to XBB RBD (Fig. 2a). While all ten nanobodies showed binding to XBB RBD, nanobodies 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, and 10 demonstrated stronger binding than the others. Next, binding of these six nanobodies to XBB S protein was evaluated with flow cytometry (Fig. 2b). This evaluation was performed to test whether the observed binding to the RBD was retained in the context of the full S protein or if any of these nanobodies bound to epitopes on the RBD that were inaccessible on the S protein. Interestingly, we observed a wide range of binding of these nanobodies to the XBB S protein. Nanobody 3 demonstrated no binding to XBB S suggesting that its binding epitope was hidden in the full S protein. While nanobodies 4 and 10 showed good binding to XBB S, nanobodies 5, 6, and 9 showed the highest levels of binding to XBB S. These lead nanobodies, called XNb 4.13, XNb 4.15, and XNb 4.14, respectively, were chosen for further characterization.

Yeast cells expressing multiple copies of one of the selected nanobodies were labeled with (a) 10 nM XBB RBD or (b) 1 nM XBB spike (S) protein, and the extent of binding was assessed with flow cytometry. Plots display fluorescence signal corresponding to binding on the Y-axis and fluorescence signal corresponding to the expression level of the nanobodies on the X-axis.

Characterization of the binding of the nanobodies to the XBB spike protein

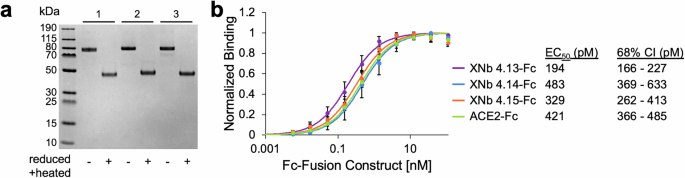

We next designed, expressed, and characterized bivalent versions of XNb 4.13, XNb 4.14, and XNb 4.15 fused to a mouse IgG Fc (Fig. 3a). We note that these constructs were not bispecific; they were bivalent because each Fc-fusion protein contained two identical copies of the same nanobody. To characterize the binding of the nanobodies to the XBB S protein, we performed titration ELISAs using a wide range of concentrations of our nanobodies (Fig. 3b). This analysis revealed that XNb 4.13-Fc, XNb 4.14-Fc, and XNb 4.15-Fc were high-affinity binders with sub-nanomolar EC50s (194, 483, and 329 pM, respectively). Our bivalent nanobodies bound to the XBB S with similar affinities or more strongly than an ACE2-Fc fusion protein (ACE2-Fc).

a A sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gel with bivalent Fc fusion constructs containing nanobodies (1) XNb 4.13, (2) XNb 4.14, and (3) XNb 4.15. b Binding of XNb 4.13-Fc, XNb 4.14-Fc, XNb 4.15-Fc, and ACE2-Fc to XBB S was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Data points are averages of six repeats from two independent assays and error bars indicate standard deviation. EC50s were calculated using global nonlinear least squares fit of the ELISA data.

Nanobodies neutralize XBB

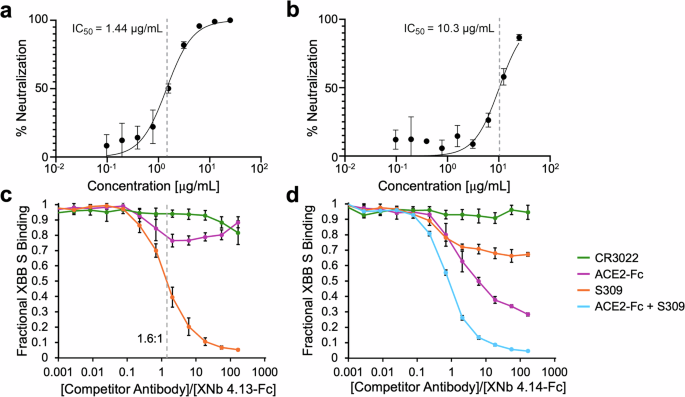

To evaluate the ability of XNb 4.13-Fc, XNb 4.14-Fc, and XNb 4.15-Fc to neutralize XBB we performed a live virus focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT). XNb 4.13-Fc and XNb 4.14-Fc, but not XNb 4.15-Fc, neutralized the XBB virus with IC50 values 1.44 µg/mL (18 nM) and 10.3 µg/mL (129 nM) for XNb 4.13-Fc and XNb 4.14-Fc, respectively (Fig. 4a, b).

Percent neutralization as a function of concentration of (a) XNb 4.13-Fc and (b) XNb 4.14-Fc with IC50 values (mean with SD and n = 3 biological replicates). c, d Competition ELISAs with XBB S (immobilized antigen) and ACE2-Fc, CR3022, S309, and mixture of ACE2-Fc and S309 antibodies (soluble competitor) were conducted to investigate the binding epitopes of (c) XNb 4.13 and (d) XNb 4.14 on XBB S. XNb nanobody binding in the presence of the competitor antibodies is shown. Data points are averages of six repeats and error bars indicate standard deviation.

To further investigate how the two neutralizing nanobodies interact with XBB S, we performed competition ELISAs with ACE2-Fc and RBD-binding antibodies CR3022 and S309 (Fig. 4c, d). CR3022 is a conformation-depending antibody isolated from a SARS-CoV-1 patient that also binds to the SARS-CoV-2 S protein38. S309 (the parent mAb of sotrovimab) was also isolated from a SARS-CoV-1 patient and neutralizes SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 viruses39. The binding sites of both antibodies on the RBD are distinct from the ACE2 binding site or the receptor-binding motif (RBM)38,39. For these experiments, immobilized XBB S proteins were pre-incubated with a range of concentrations of the competitor (ACE2-Fc, CR3022, or S309). Then, a constant amount of our nanobody constructs (6 nM final concentration) was added to assess the nanobody’s ability to bind to XBB S.

The binding of XNb 4.13-Fc was completely blocked by a 100-fold higher concentration of S309 (Fig. 4c). This result suggests that XNb 4.13 and S309 have significantly overlapping binding epitopes. As seen in Fig. 4c, a slight molar excess of S309 ( ~ 1.6:1) was needed for 50% inhibition of the binding of XNb 4.13-Fc to XBB S. The binding of XNb 4.13-Fc to XBB S was not as significantly impacted by CR3022 or ACE2-Fc suggesting that its binding epitope is distinct from that of CR3022 or the RBM. Competition experiments with XNb 4.14-Fc revealed that both ACE2-Fc and S309 slightly inhibited the binding of the nanobody suggesting that its binding epitope is at least partially within the RBM. XNb 4.14-Fc retained 28% binding to XBB S in the presence of 100-fold higher concentration of ACE2-Fc and 67% binding to XBB S in the presence of 100-fold higher concentration of S309. The binding of XNb 4.14-Fc was completely inhibited when both ACE2-Fc and S309 were present in 100-fold higher concentrations suggesting that the binding epitope of XNb 4.14 overlapped partially with those of S309 and RBM. Binding of XNb 4.14-Fc was not impacted by CR3022.

Protective efficacy of nanobodies in K18-hACE2 mice

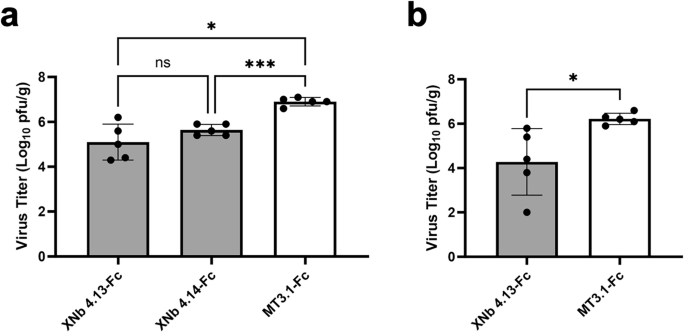

Based on these results, we proceeded to characterize the ability of XNb 4.13 and XNb 4.14 nanobodies with XBB challenge experiments in mice. First, K18-hACE2 mice (females, 4 weeks old, n = 5/group) were treated by intraperitoneal injection with 100 µg (5 mg/kg) of XNb 4.13-Fc, XNb 4.14-Fc, or a control bivalent nanobody Fc fusion protein, bivalent MT3.1-Fc40 24 h prior to XBB infection. Three days after infection, viral lung titers were determined by plaque assay. Treatment with XNb 4.13-Fc or XNb 4.14-Fc significantly reduced viral titers in the lungs of challenged mice compared to the control antibody (Fig. 5a). The mean viral titers in the lungs of mice treated with XNb 4.13-Fc or XNb 4.14-Fc were 65- or 19-fold lower than that of mice treated with the control Fc fusion protein, respectively.

K18-hACE2 mice were treated with XNb 4.13-Fc, XNb 4.14-Fc, or control construct bivalent MT3.1-Fc through (a) intraperitoneal or (b) intranasal route and infected with XBB virus 24 h later. Three days after infection, viral lung titers were determined by plaque assay. Each dot represents an individual animal in each group. Data represent means and standard deviations from 5 mice per group. ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, ns: not significant, determined by (a) Brown-Forsythe and Welch ANOVA tests or (b) Welch’s t-test.

Another mode of delivery, i.n. administration was explored in comparison with the i.p. administration. We proceeded with XNb 4.13-Fc for this study because XNb 4.13-Fc showed more potent neutralization than XNb 4.14-Fc in vitro and comparable reduction in lung viral titers from the previous challenge study. K18-hACE2 mice (females, 4 weeks old, n = 5/group) were treated intranasally with 100 µg (5 mg/kg) of XNb 4.13-Fc or the Fc-fused bivalent control nanobody, MT3.1-Fc40. Twenty-four hours after treatment, mice were infected intranasally with 105 pfu of the XBB virus, and viral titers in the lungs were determined three days after infection by plaque assay. The mean viral lung titer in mice treated with XNb 4.13-Fc was 82-fold lower than that of mice administered with the control Fc fusion protein (Fig. 5b).

Discussion

In this work, we have identified three XBB S protein-binding nanobodies, two of which neutralize the XBB variant in vitro and significantly reduce viral load in the lungs of mice challenged with XBB. When XNb 4.13-Fc was given intranasally, the lung viral titers were also significantly reduced compared to the control mice group. This indicates that our nanobody construct maintains efficacy in reducing viral lung titers through both i.p. and i.n. administration routes. In future studies, the efficacy of XNb 4.13-Fc and XNb 4.14-Fc in vivo could be compared to those of other antibodies such as S309. While this study demonstrated the efficacy of pre-infection treatment with the nanobody constructs, in future work, it would also be useful to evaluate the efficacy of post-infection treatment. Such a study could use separate groups of K18-hACE2 mice in which the nanobodies are administered at different times post-infection (e.g., 1, 6, 12, and 24 h post-infection with XBB virus).

XNb 4.13, XNb 4.14, and XNb 4.15 were developed through the in vitro screening of a synthetic nanobody library37 and demonstrated sub-nanomolar levels of binding towards the XBB S protein. This work demonstrates the utility of using a completely in vitro method for the development of high-affinity XBB-targeting nanobodies that neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 XBB variant. Compared to conventional camelid immunization, sorting a synthetic nanobody library through rounds of MACS and FACS is a high-throughput method that can be adapted to various antigenic targets. These results will guide future work to rapidly and easily develop nanobodies that target the newest SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern.

While the focus of this study was on targeting the SARS-CoV-2 XBB variant, future work could explore the breadth of protection offered by XNb 4.13 and XNb 4.14. Conducting neutralization experiments with EG.5.1, an XBB subvariant41, KP.3.1.1, a recent Omicron variant from the JN.1 lineage that is the most widely circulating variant in the United States as of November 202442, and other variants that will undoubtedly emerge in the future, would allow us to gauge the breadth of protection of our nanobody constructs. Since EG.5.1 and KP.3.1.1 have an F465L mutation in the receptor-binding site43, and since the epitope for XNb 4.14 lies partially within the RBM, it is possible that the neutralization potency of XNb 4.14 against these variants will be lower than that against XBB. We further hypothesize that XNb 4.13 will maintain its neutralization potency against EG.5.1, which has no additional mutations relative to XBB in the S309 binding site, whereas the potency may be reduced against KP.3.1.1, which does have additional mutations in this region39,43. Since the binding of nanobodies can also be affected by mutations outside the epitope, these hypotheses will have to be tested experimentally. If needed, mutagenesis of these nanobodies and additional screening against SARS-CoV-2 RBDs can be conducted to further improve their affinity and enhance the breadth of protection against circulating variants.

The avidity and breadth of protection could be further enhanced by designing bi-specific or multi-specific nanobody constructs that combine two or more nanobodies targeting different epitopes on the S protein. This approach could not be used in the current study because of the partial overlap between the epitopes of XNb 4.13 and XNb 4.14. The design of multivalent multi-specific constructs44 presenting multiple nanobodies identified by in vitro selection represents a powerful approach to designing potent binders that neutralize a broad range of viral variants and delay the emergence of resistant escape mutants.

Materials and methods

XBB RBD and S expression and purification

DNA sequences encoding XBB strain SARS-CoV-2/human/USA/CA-CDC-STMMV7TMMQMB/2022 RBD and S proteins with C-terminal His-tags were synthesized and cloned into the pcDNA3.1(-) expression vector by Gene Universal Inc. (Newark, DE). These plasmids were transfected into Expi293F cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the ExpiFectamine 293 Transfection Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Proteins were expressed over 6 days and then the cell culture was centrifuged at 6000 × g for 10 min to harvest the cell supernatant. The RBD and S proteins were purified by Ni-NTA chromatography using HisPur Ni-NTA resin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). First, the cell supernatant was mixed with 1 mL of resin overnight at 4 °C. The next day, the resin slurry was loaded into a gravity flow column (G-Biosciences) and then washed with 90 mL immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) equilibration buffer (100 mM tris HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). RBD and S proteins were eluted in 9 mL of elution buffer (100 mM tris HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 400 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) and the eluate was then concentrated with a 10 kDa molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) centrifugal filter (Millipore Sigma). RBD and S proteins were further purified via size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column (Cytiva) in PBS. Protein concentration and purity were determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Scientific) and Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), respectively.

XBB RBD and S biotinylation

XBB RBD and S proteins were biotinylated using the EZ-Link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin reagent (Thermo Scientific) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Excess reagent was removed by buffer exchanging with a 10 kDa MWCO centrifugal filter (Millipore Sigma) into TBS (20 mM tris HCl, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). The extent of biotinylation was determined by mixing the biotinylated protein with streptavidin45 (Addgene plasmid #46367; http://n2t.net/addgene:46367; RRID:Addgene_46367; was a gift from Mark Howarth) and running an SDS-PAGE gel at 4 °C. Briefly, 1 µg of biotinylated protein was mixed with 3 times molar excess of streptavidin for 20 min at room temperature. The mixture sample was run on SDS-PAGE gel; standards consisting of 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, and 0.2 µg of the same protein were run in separate lanes on the same gel. The amount of unbound biotinylated protein in the mixture sample lane was quantified by comparison to the standards to determine the percentage of biotinylated protein.

SDS-PAGE

Proteins were diluted in Nu-PAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen). Protein samples and PageRuler Plus Prestained Protein Ladder (Thermo Scientific) were loaded into wells of a 4–12% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and the gel was run for 50 min at 120 V. The gel was stained with Imperial Protein Stain (Thermo Scientific), destained, and then imaged using the ChemiDoc MP imaging system (Bio-Rad).

Yeast cell culture

Yeast cells expressing the nanobody library37 (a gift from the Kruse lab at Harvard University) were cultured at a density of 107 cells/mL in tryptophan deficient SD-Trp media (3.8 g/L yeast synthetic drop-out medium supplements without tryptophan, 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base, 20 g/L glucose, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, pH 6.0) at 250 rpm and 30 °C. Expression of nanobodies on the yeast cell surface was induced by incubation of the yeast in SG-Trp media (3.8 g/L yeast synthetic drop-out medium supplements without tryptophan, 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base, 20 g/L galactose, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, pH 6.0) at 107 cells/mL and by incubating overnight at 250 rpm and 25 °C.

Magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS)

Two rounds of MACS were conducted to identify XBB RBD-binding nanobodies. For both MACS screens, two negative selections against magnetic Dynabeads Biotin Binder beads (Invitrogen) followed by one positive selection against XBB RBD-coated beads were performed. For the MACS Round 1 positive sort, 107 Dynabeads coated with 12.5 µg biotinylated XBB RBD were prepared, and for the MACS Round 2 positive sort, 106 Dynabeads coated with 1.25 µg biotinylated XBB RBD were prepared. The manufacturer’s protocol was used to prepare the Dynabeads. In brief, the beads were washed twice with PBS containing 0.1% BSA using a magnet and were incubated with the appropriate amount of biotinylated XBB RBD in 500 µL (MACS Round 1) or 50 µL (MACS Round 2) 0.1% BSA in PBS overnight at 4 °C with rotation. Dynabeads were washed and incubated in just 0.1% BSA in PBS for negative sorts against unlabeled beads. The next day, the Dynabeads were washed with 0.1% BSA in PBS and resuspended in 100 μL 0.1% BSA in PBS. Unlabeled Dynabeads for the first negative selection were added to 1010 induced library cells (for MACS Round 1) or 109 induced MACS Round 1 cells (for MACS Round 2) and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with rotation. Next, unbound yeast cells were collected with a magnet and bound yeast cells and the Dynabeads were discarded. This negative selection was repeated once more with unlabeled beads. To perform the positive selection, the yeast cells were incubated with XBB RBD-coated beads for 1 h at room temperature with rotation. Unbound cells were collected and discarded, and the beads were washed 5 times with 0.1% BSA in PBS and a magnetic tube rack to completely remove unbound yeast cells. The yeast immobilized on the beads were transferred to 5 mL of SD-Trp media and were cultured at 30 °C and 250 rpm for 48 h.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

Four rounds of FACS were conducted with XBB RBD. 107 Nanobody-expressing yeast cells were labeled with 100 nM, 50 nM, 50 nM, or 5 nM biotinylated XBB RBD for FACS Rounds 1, 2, 3, or 4, respectively. Cells were also labeled with an anti-HA tag rabbit antibody (Invitrogen, 1:200) and incubated at room temperature with rotation for 20 min. The cells were washed with 0.1% BSA in PBS and then labeled with streptavidin R-phycoerythrin conjugate (Invitrogen, 1:250) and donkey anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, 1:500) for 10 min on ice. Cells were washed with 0.1% BSA in PBS and sorted on a BD FACSAria Fusion cytometer. The selected yeast were cultured for 48 h in 5 mL SD-Trp media at 30 °C and 250 rpm.

Individual nanobody selection

Yeast cells from FACS Rounds 4.1 and 4.2 were plated on SD-Trp plates (3.8 g/L yeast synthetic drop-out medium supplements without tryptophan, 6.7 g/L yeast nitrogen base, 20 g/L glucose, 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin, 15 g/L agar) and incubated for 48 h at 30 °C. 12 colonies from each culture were used to inoculate 5 mL SD-Trp media and cultured for 48–36 h at 30 °C and 250 rpm. From each culture, plasmid DNA was extracted using the Zymoprep Yeast Plasmid Miniprep II kit (Zymo Research) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The extracted DNA was used to transform NEB 5-alpha Competent E. coli cells (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The E. coli was cultured in 5 mL LB media with 100 µg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C with rotation. Plasmid DNA was extracted from each culture using the E.Z.N.A. Plasmid Mini Kit I (Omega Biotek) and sequenced by MCLAB (San Francisco, CA).

Flow cytometry

Induced yeast cells were labeled with a range of concentrations of biotinylated XBB RBD or S protein, anti-HA tag rabbit antibody, streptavidin R-phycoerythrin conjugate, and donkey anti-rabbit IgG Alexa Fluor 488 as described above. Binding was quantified on a CytoFLEX S flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter).

Expression and purification of bivalent Fc fusion XNb nanobodies

Genes encoding XNb 4.13, XNb 4.14, and XNb 4.15 fused to a mouse IgG Fc were synthesized and cloned into the TGEX-HC plasmid (Antibody Design Labs) by Gene Universal (Newark, DE). Plasmids were transfected into Expi293F cells, expressed, and harvested as described above. Fc fusion proteins were purified using a 1 mL HiTrap MabSelect SuRe column (GE) and the manufacturer’s protocol. The cell supernatant was loaded into the HiTrap MabSelect SuRe column, washed with 10 column volumes of binding buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.2) and eluted with a linear gradient with a constant slope over 20 column volumes between the original phosphate buffer and a citrate buffer (0.1 M sodium citrate, pH 3.5). Fc fusion proteins were then dialyzed into PBS and their concentration and purity were determined by BCA assay (Thermo Scientific) and SDS-PAGE, respectively.

XNb enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) binding analysis

0.2 µg of XBB S protein in 100 µL of PBS was coated onto each well of a Nunc MaxiSorp 96-well flat-bottom plate (Invitrogen). After an incubation overnight at 4 °C, the wells were blocked for 1 h with 200 µL of PBST (PBS with 0.05% Tween-20) containing 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (BSA). Following three washes with PBST, a 1 in 3 serial dilution was performed across each row of the plate with a 1000 nM starting concentration of XNb 4.13-Fc, XNb 4.14-Fc, or XNb 4.15-Fc in 1% BSA in PBST. One hour later, the wells were washed three times with PBST and goat anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated antibody (Rockland; 1:5000 dilution) in 1% BSA in PBST was added to each well for another 1 h incubation at room temperature. Following the incubation, the plate was washed three times with PBST. Then, the plate was developed with 100 µL of TMB substrate solution (Thermo Scientific) for 2.5 min and the reaction was quenched with 100 µL of 160 mM sulfuric acid. The absorbance of each well at 450 nm was measured.

Binding data were fit to a binding isotherm using global nonlinear least squares regression46. Maximum absorbance values for each repeat were used to normalize the data. A single EC50 value for each nanobody was determined as a fitted parameter across all six repeats.

Competition ELISAs

Each well of a Nunc MaxiSorp 96-well flat-bottom plate (Invitrogen) was coated with 0.2 µg of XBB S protein in 100 µl of PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After the incubation, the plate was washed three times with PBST. Samples (100 μL per well) of 1% BSA in PBST containing 1 in 3 serial dilutions (initial concentration of 1000 nM) of S309, CR3022 (two RBD-binding mAbs), or ACE2-Fc were added to the wells and were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Then, 6 nM of Fc fused XNb 4.13 or XNb 4.14 were added to the wells and were incubated for another hour. Following three washes with PBST, HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (Rockland, 1:5000) in 1% BSA in PBST was added to each well. After 1 h incubation, the plate was washed three times with PBST before adding 100 µL of TMB substrate solution (Thermo Scientific). After 2.5 min, the reactions were stopped with 100 µL of 160 mM sulfuric acid and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured.

Biosafety and approvals

All research with SARS-CoV-2 was performed under biosafety level 3 agriculture (BSL-3 AG) containment at the Influenza Research Institute with an approved protocol (B00000263) reviewed by the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Institutional Biosafety Committee. The laboratory is designed to meet and exceed the standards outlined in Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (6th edition).

Animal studies at the University of Wisconsin-Madison were performed under an approved protocol (Protocol Number: V006426) reviewed by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. To minimize pain, virus infections were performed under isoflurane anesthesia. Animal groups were not blinded to the researchers.

Virus and cells

The XBB isolate, hCoV-19/Japan/TY41-795/2022 (Accession ID: EPI_ISL_16355653), used in these studies was propagated on Vero E6 TMRSS2 cells (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan) which were maintained in high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotic/antimycotic solution along with G418 (1 mg/mL). For consistency, virus titrations were performed on Vero E6 TMPRSS2-T2A-ACE2 cells (NIAID Vaccine Research Center; Dr. Barney Graham). This cell line was maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.3) and antibiotic/antimycotic solution along with puromycin (10 µg/mL). Both cells are tested monthly for mycoplasma contamination by PCR and are confirmed to be mycoplasma-free.

Focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT)

A 2-fold dilution series of Fc-fused nanobodies starting at a concentration of 50 µg/mL was mixed with approximately 800 focus-forming units of the XBB virus and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The antibody-virus mixture was inoculated onto Vero E6/TMPRSS2 cells in 96-well plates and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. An equal volume of methylcellulose solution was added to each well. The cells were incubated for 16 h at 37 °C and then fixed with formalin. After the formalin was removed, the cells were immunostained with a mouse monoclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-1/2 nucleoprotein (clone 1C7C7, Sigma-Aldrich, catalog #MA5-29982, 1:10,000 dilution), followed by a horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (ThermoFisher, catalog #31430, 1:2000 dilution). The infected cells were stained with TrueBlue Substrate (SeraCare Life Sciences) and then washed with distilled water. After cell drying, the focus numbers were quantified by using an ImmunoSpot S6 Analyzer, ImmunoCapture software, and BioSpot software (Cellular Technology). The IC50 value was then calculated from the normalized percent neutralization using a four-parameter nonlinear regression in Graphpad Prism. Percent neutralization was calculated as (N=100 % ,times ,(1-frac{{F}_{N}}{{F}_{c}})), where N is the percent neutralization, ({F}_{N}) is the number of foci in the presence of the Fc-fused nanobody construct, and ({F}_{c}) is the number of foci in the presence of PBS control.

Challenge experiments

K18-hACE2 mice (females, 4-weeks old, n = 5/group) were treated intraperitoneal (i.p.) or intranasally (i.n.) with 100 µg (5 mg/kg) of XNb 4.13-Fc, XNb 4.14-Fc, or a bivalent control MT3.1-Fc, 24 h prior to their infection with 105 plaque-forming units (pfu) of the XBB virus. Three days after infection, lung tissue was collected to measure viral loads by standard plaque assay.

Responses