Potential locations for non-invasive brain stimulation in treating ADHD: Results from a cross-dataset validation of functional connectivity analysis

Introduction

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity-Disorder (ADHD) is one of the most prevalent neurobehavioral problems. ADHD afflicts children between 6 to 17 years of age with a worldwide prevalence of around 7%. The effect of ADHD would persist into adulthood in a substantial proportion of children, which is characterized by hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity [1,2,3]. ADHD impacts many aspects of an individual’s wellbeing, including physical health, and academic, social, and occupational functioning [4]. However, pharmacologic treatment for ADHD is far from satisfactory [5, 6]. New therapies for ADHD are urgently needed.

Noninvasive brain stimulation (NIBS), such as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), and scalp electro-acupuncture, has recently been considered as a promising treatment for ADHD [7,8,9]. These techniques are safe with no serious adverse events reported [10, 11], which have also been found useful in facilitating the understanding of ADHD pathophysiology [12]. Although previous studies have supported the effectiveness of NIBS for ADHD, some have reported no significant effect compared to sham treatment [13]. The stimulation site might be a relevant factor that limit the efficacy of NIBS for ADHD. Heretofore, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) is the most commonly used site for the treatment of ADHD. A review and meta-analysis showed that rTMS and tDCS targeting dlPFC produced trend-level improvements in inhibition and processing speed on patients with ADHD, but not in attention. The results provided little evidence for clinical improvement of NIBS on dlPFC, calling for more optimal stimulation sites for ADHD [14]. Thus, the exploration of new stimulation targets may improve the efficacy of NIBS in treating ADHD.

Numerous studies have showed that modulating the functional connections between the target regions and the rest regions in the brain is one of the most important effect of NIBS [15,16,17,18]. FC analysis is the most commonly used method for exploring the functional connections between brain regions [19, 20]. FC calculates the statistical relationship between the time series of different brain regions, which shows how different brain regions interact with each other over time [21, 22]. AS NIBS can only directly stimulate brain surface regions, FC is intended to be used in this study to extend the coordinates of brain regions obtained by meta-analysis to the brain surface regions, in order to provide potential targets for NIBS.

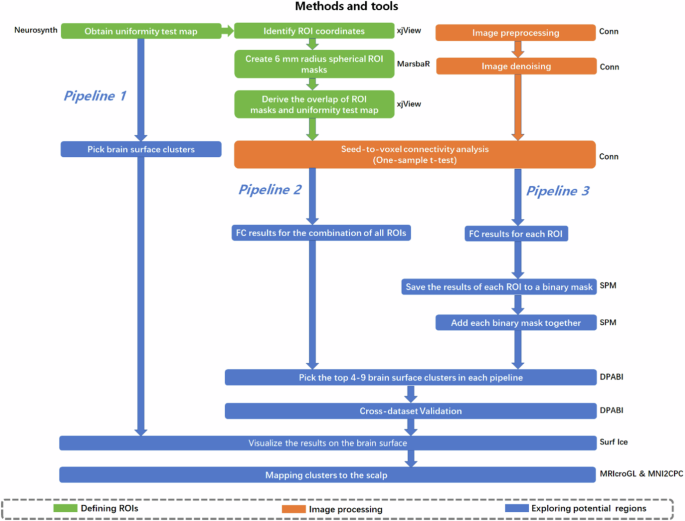

Recently, we developed a protocol to explore potential stimulation targets for brain disorders, which applied FC to extend the findings from meta-analysis [23]. Attempts have been made in depression, autism, schizophrenia, sleep disorders, and etc [23,24,25,26]. In this study, we improved the protocol by using two independent datasets to validate the results from FC, aiming to provide promising and generalizable NIBS targets for ADHD (Fig. 1).

First, identifying ADHD associated ROIs using Neurosynth. Second, conducting FC analysis to extend findings from Neurosynth. Third, exploring brain surface clusters and scalp locations through three pipelines. ROI: region of interest; FC: functional connectivity.

Methods

Identifying ADHD-associated brain regions from meta-analysis

To determine ADHD-associated regions of interests (ROIs), we used Neurosynth [27] (http://neurosynth.org/) as a metadata reference of the neuroimaging literature. Neurosynth is a platform for automatically synthesizing the results of neuroimaging studies, which included 14371 fMRI studies and 1334 term-based meta analyses results. Under the search term ‘disorder adhd’, 124 fMRI studies were identified, and a uniformity test map was generated to identify ADHD-associated brain regions. The complete list of the 124 fMRI studies extracted from Neurosynth can be found in Supplementary Material 4.

Neurosynth offers two types of statistical inference maps through the meta-analysis: uniformity test and association test maps. The association test maps provide information about the relative selectivity of regions that activate during a particular process, while the uniformity test maps provide information about the consistency of activation for a specific process. In this study, our focus was on identifying brain regions related to ADHD in general, rather than those specific to ADHD. Therefore, we utilized the uniformity test map. To produce the uniformity test map, a false discovery rate (FDR) adjusted p value of 0.01 was applied. To create ADHD–related ROIs, the coordinates with peak z-scores within all clusters larger than 30 voxels on the uniformity test map were identified using the xjView toolbox (www.alivelearn.net/xjview). Spherical masks with a radius of 6 mm, centered on the peak coordinates, were created using MarsBaR version 0.44 (http://marsbar.sourceforge.net/). In order to maintain regional specificity and include only voxels from the original uniformity test map, the ROIs were refined by overlapping the original uniformity test map with the MarsBaR masks.

Participants and MRI data acquisition

The structural and functional MRI data were acquired from the Peking University dataset and the New York University Child Study Center dataset of the ADHD-200 Sample. Concisely stated, the inclusion criteria encompass individuals who fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of ADHD, fell within the age range of 8 to 17 years, possessed an IQ score of 80 or above, were free from any other psychiatric disorders, were right-handed, were lacked of any phobias, and had abstained from psychotropic medications for at least 24 hours prior to the MRI scan. Details of the inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and MRI data acquisition are available at the website (https://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/indi/adhd200/) and in the Supplementary Material 2.

Only patients who have both resting-state fMRI (RS-fMRI) and three-dimensional structural T1-weighted MRI (3D-T1) were included. In order to match the baseline characteristics of the two databases, we deleted the subjects with ADHD in the New York database from the oldest to the youngest until there was no significant difference between the two datasets in age, gender, and ADHD types (as test by Chi-square test). Subsequently we calculated the head motion of the subjects with ADHD using Data Processing and Analysis for Brain Imaging (DPABI) version 7 (http://rfmri.org/dpabi) (Yan et al., 2016) and Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM) 12 (www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/) to eliminate the first ten volumes of the RS-fMRI data and assessed the head motion of each subject using the mean relative root mean square (RMS). Subjects whose mean relative RMS exceeded 0.2 mm or whose maximum head motion exceeded 3 mm were excluded. Totally, 31 subjects from the New York database and 7 subjects from the Peking database were excluded because of head motion. Finally, a total of 116 patients were included, with 41 patients in the Peking University dataset and 75 in the New York University Child Study Center dataset. The study used anonymized data from a publicly available database, which does not require additional ethical approval. All the original studies related to the databases had already obtained the necessary ethical approvals and participants’ consents before the investigations.

Image preprocessing

After removing the first 10 volumes, the RS-fMRI data of the 116 subjects with ADHD were preprocessed (using Conn’s default preprocessing pipeline) and analyzed in Conn version 22a (https://web.conn-toolbox.org/) (Whitfield-Gabrieli and Nieto-Castanon, 2012) and SPM 12.

During preprocessing, functional images underwent slice-timing correction, realignment, normalization to 3 × 3 × 3 mm3 Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space, and smoothing to 6 × 6 × 6 mm3. The Artifact Detection Tool (www.nitrc.org/projects/artifact_detect/) was utilized to detect outliers ( > 3 SD and >0.5 mm) for subsequent scrubbing regression. Structural images were segmented into gray matter, white matter (WM), and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), then normalized to MNI space. Linear regression using WM and CSF signals (CompCor; 10 components for WM and 5 for CSF), linear trend, subject motion (six rotation/translation motion parameters and their first-order temporal derivatives), and outliers (scrubbing) was performed to eliminate confounding effects. Subsequently, the residual blood oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) time series underwent band-pass filtering (0.01–0.1 Hz).

Functional connectivity analysis

Using the ROIs identified from the meta-analysis, a seed-to-voxel FC analysis was performed, with Peking and New York databases separately.

Firstly, the residual BOLD time course from the ADHD ROIs of each subject were extracted to generate subject-level correlation maps. Then the pearson’s correlation coefficients between these ROIs and all other brain voxels were calculated. Subsequently these correlation coefficients were transformed into z-scores to enhance normality and meet the assumptions of generalized linear models.

Then, a one-sample t-test was conducted using all subject-level seed maps of seed-to-voxel connectivity, which allows us to obtain a group-level correlation map that represents the overall connectivity patterns. As used in a previous study, we applied a brain surface mask to ensure that only regions on the brain surface were included in the analysis [23].

Exploring potential brain surface targets for ADHD

To explore potential brain surface regions for NIBS, three distinct pipelines were conducted (Fig. 1). Due to the reduction in electrical field generated by NIBS as the cortex-scalp distance increases, we applied a brain surface mask to ensure only voxels within 25 mm from the scalp were included in the exploration [28]. The 25 mm brain surface mask is visible in the Fig. S3 of the Supplementary Material. In pipelines 2 and 3, a voxel-wise level threshold of p < 0.001 and a cluster level family-wise error (FWE) of p < 0.05 were applied to obtain group-level correlation maps of ROIs. During the step of picking brain surface clusters, a cluster size threshold of 30–800 voxels was applied to avoid false discovery and ensure the clinical significance of the clusters.

Pipeline1. Potential regions were directly selected on the brain surface from the original uniformity test map obtained by Neurosynth. Specifically, the T value of the uniformity test map was increased 0.5 per step until 4–10 clusters were identified on the brain surface mask. These clusters represent brain regions that could be directly involved in the pathophysiology of ADHD disorders.

Pipeline2. An ADHD network, created by combining the ROIs identified from the meta-analysis, was used as a seed in the seed-to-voxel connectivity analysis. From this analysis, we identified the top 4–10 surface clusters with the largest peak z-scores on the group-level correlation map. The positive and negative correlation maps were evaluated separately. The results from this pipeline may identify the brain surface regions with the strongest correlation with the ADHD network.

Pipeline3. In this pipeline, group-level correlation maps of each ADHD-ROI were saved as binary masks. These masks were then combined by adding them together, resulting in a third-level map that included positive or negative correlation maps separately. The intensity of each voxel in the third-level map reflected the number of ADHD-ROIs that were correlated with that particular voxel. From this map, we identified 4–10 surface clusters with the highest peak z-scores among all clusters. These clusters may represent brain surface regions correlated with the largest number of ADHD-ROIs.

To explore whether different types of ADHD influence the targeted brain regions, we further conducted a subgroup analysis in pipeline 2 by dividing patients based on different ADHD types. Due to the insufficient sample size of the ADHD-Hyperactive/Impulsive (ADHD-H) type in our subjects, we only conduct analyses on ADHD-Inattentive (ADHD-I) and ADHD-Combined (ADHD-C) types.

Cross-dataset validation

To increase the generalizability of the results, cross-dataset validation was conducted in pipeline 2 and pipeline 3. During the step of exploring brain surface clusters, pipeline 2 and pipeline 3 were conducted using Peking and New York databases separately. Then, the results were cross-dataset validated by taking the overlap of the clusters identified from the two datasets.

Mapping clusters and coordinates to the scalp

In pipeline 1, the MNI coordinate with the peak T-value in a cluster was extracted. In pipeline 2 and pipeline 3, the average of all voxel MNI coordinates in an overlapping cluster was calculated using xjView toolbox (www.alivelearn.net/xjview). Then, the clusters with coordinates were visualized on the brain surface using Surf Ice (www.nitrc.org/projects/surfice/) and mapped to the scalp using MRIcroGL (https://www.nitrc.org/projects/mricrogl/). The scalp location of the clusters and coordinates were referenced by 10–20 system [29].

To enable rapid and accurate manual localization in clinical practice, the MNI coordinates were further transferred to Pnz and Pal parameters in continuous proportional coordinates (CPC) using MNI2CPC (https://transcranial-brain-atlas.org/mni2cpc/). MNI2CPC offers a neuro-navigation-system-free approach for localizing any MNI cortical target on the scalp in a clinical-friendly way, whose performance has been validated cross individuals, races, and diseases [28, 30].

Results

Meta-analysis results

Eighteen clusters were identified from the meta-analysis. These clusters included the bilateral insula, the right caudate, the right dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), the left anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), bilateral dlPFC, ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), bilateral putamen, anterior medial prefrontal cortex (amPFC), bilateral temporo-parietal junction (TPJ), the left inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), the left inferior parietal lobule (IPL) and the right precuneus. The peak coordinates of these ROIs are provided in Table 1.

Demographics of the participants

Totally 116 patients were included in the resting-state FC analysis, with 41 in the Peking University dataset (12 females and 29 males; aged 10.71 ± 2.16 years) and 75 in the New York University Child Study Center dataset (23 females and 52 males; aged 10.36 ± 2.42 years). There was no significant difference between patients of the two datasets in age, gender, and ADHD types. Details of the demographics were presented in the Supplementary Material 3.

Potential locations for NIBS in ADHD

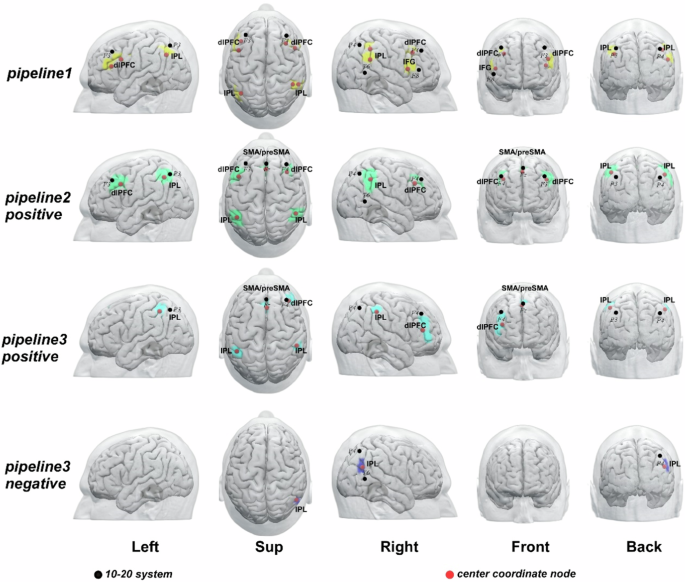

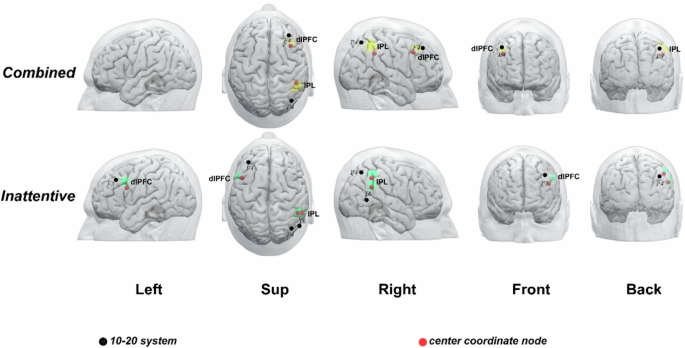

After cross-dataset validation, potential brain surface clusters and their scalp locations were identified from the three pipelines (Table 2 and Fig. 2) and subgroup analysis (Table 3 and Fig. 3).

Pipeline 1, meta-analysis; Pipeline 2, FC analysis based on the ADHD network; Pipeline 3, FC analysis based on each ADHD-ROI. The ‘positive’ represents brain regions positively correlated with ADHD network or ROI; ‘negative’ represents brain regions negatively correlated with ADHD network or ROI. Abbreviations: L, left; R, right; dlPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; IFG: inferior frontal gyrus; IPL: inferior parietal lobule; SMA: supplementary motor area.

Note: ADHD is classified into three types: ADHD-inattentive type, ADHD-hyperactivity and impulsivity type, and ADHD-Combined type. However, due to the limited sample size of individuals with the ADHD-hyperactivity and impulsivity type, it has not been analyzed in detail. Abbreviations: L, left; R, right; dlPFC: dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; IPL: inferior parietal lobule.

In pipeline1, bilateral dlPFC, right IFG, and bilateral IPL were identified as brain surface regions that may be directly involved in the pathophysiology of ADHD. The 10–20 system coordinates corresponding to the centers of these regions were located approximately at inferior and posterior to F3, inferior to F3, inferior and anterior to P3, posterior to F4, anterior and inferior to P4, superior and anterior to T6, posterior to F8.

In pipeline2, bilateral dlPFC, bilateral IPL, and SMA/preSMA were identified as brain surface regions positively correlated with the ADHD network. The 10–20 system coordinates corresponding to the centers of these regions were located approximately posterior and inferior to F3, anterior to P3, approximately at F4, anterior and inferior to P4, approximately at Fz. No cluster was found to be negatively correlated with the ADHD network.

In Pipeline3, right dlPFC, bilateral IPL, and SMA/preSMA were identified as brain surface regions positively correlated with ADHD ROIs. The 10–20 system coordinates corresponding to the centers of these regions were located approximately at anterior to P3, inferior to F4, anterior to P4, approximately at Fz respectively. The right IPL were found to be brain surface regions negatively correlated with ADHD ROIs. The 10–20 system coordinates corresponding to the centers of these regions were located approximately at Midpoint of P4-T6.

The results of subgroup analysis identified the right dlPFC and the right IPL as brain surface regions positively correlated with ADHD-C type. The right IPL and left dlPFC were identified as brain surface regions positively correlated with ADHD-I type. The 10–20 system coordinates for the centers of ADHD-C type regions were located inferior and anterior to P4, and posterior to F4, while those for ADHD-I type regions were located inferior and posterior to F3, inferior and anterior to P4, and superior to T6, respectively (Table 3 and Fig. 3).

The CPC coordinates and depth from the scalp of each brain surface cluster in all pipelines were presented in Tables 2 and 3. The results of pipeline 2 and pipeline 3 of Peking and New York databases before cross-dataset validation were presented in the Figs. S1 and S2 of the Supplementary Material.

Discussion

In this study, we conducted a cross-dataset validation based on the results of meta-analysis and resting-state FC analysis to identify potential targets for NIBS in treating ADHD. By comparing the results from three different pipelines, we found several brain regions that showed their importance in most of the pipelines, which indicated they could be potential targets for NIBS. These regions include bilateral dlPFC, right IFG, bilateral IPL, and SMA/preSMA. Furthermore, we found that different types of ADHD patients exhibited abnormalities in distinct brain functional areas, with ADHD-C type corresponding to the right dlPFC and the right IPL, and ADHD-I type corresponding to the left dlPFC and right IPL. Additionally, the scalp locations corresponding to these brain targets were provided based on 10–20 system and CPC coordinates.

Location plays a crucial role in the treatment of ADHD using NIBS. The precise targeting of specific brain regions is of utmost importance to maximize the effectiveness of the treatment [31, 32]. In this study, we identified the dlPFC as a potential target of NIBS for ADHD in all three pipelines. The dlPFC is a commonly used targets for treating ADHD. Previous research has indicated that tDCS on the dlPFC can improve symptoms of inattention in individuals with ADHD, but it does not improve symptoms of impulsivity and hyperactivity [9, 33]. This result may be related to the imprecision of targeting the stimulation site. The optimal position of the dlPFC for ADHD remains unclear currently. In this study, we applied cross-dataset validation based on the results of meta-analysis and FC analysis. Ultimately, we obtained target locations as posterior to F3 and F4, and we further computed the coordinates of these targets in the CPC, which is advantageous for enhancing the precision of clinical localization.

The subgroup analysis further suggested right dlPFC for patients with ADHD-C and left dlPFC for patients with ADHD-I. The dlPFC, particularly the left dlPFC, is often used as a target for NIBS treatment of ADHD because this region plays a very important role in executive function and working memory [34,35,36]. However, in tDCS studies, the right dlPFC has not been studied in depth. Right dlPFC are well documented in response inhibition [37, 38]. A previous study showed that the right dlPFC has a crucial role in inhibitory control in children with ADHD and the tDCS effect in children with ADHD in prepotent inhibition is symptom severity- dependent [39]. Thus, this result provides a basis for subsequent NIBS study to accurately select targets according to ADHD types.

In pipeline1 we identified the right IFG as a potential region. The IFG is a critical region in the fronto-striatal pathway of ADHD [40,41,42,43,44,45]. In ADHD children, researchers have reported reduced FC relative to healthy controls between the right IFG and basal ganglia, parietal lobes, and cerebellum during motor response inhibition and WM tasks, as well as between IFG and cerebellum, parietal, and striatal brain regions during sustained attention, interference inhibition, and time estimation [46, 47]. Thus, consistent with our findings, IFG may be one of the most consistently implicated regions in the pathophysiology of ADHD.

According to the results of the aforementioned studies, it appears that both the right and left prefrontal cortices play a significant role in improving inhibitory control and reducing impulsivity in individuals with ADHD. Based on these findings, it is possible that a more robust enhancement of inhibitory control could be achieved by employing double anodal tDCS. This involves placing one electrode over the left DLPFC (F3 on the 10–20 EEG system) and another electrode on the right IFG (F8), while positioning the reference electrode in a cephalic position, such as the vertex.

The scalp location corresponding to the SMA/pre-SMA was identified as a potential target for ADHD. Previous meta-analysis studies have shown that ADHD patients have reduced brain activation in SMA and pre-SMA [48,49,50,51]. The SMA and pre-SMA is frequently engaged during inhibition tasks like the go/no-go task [51,52,53,54,55] and the stop-signal task [56], indicating their significance within the response inhibition system [57]. The dysfunction of the SMA is an important mechanism underlying the excessive involuntary movements observed in patients with ADHD [48]. Thus, targeting the SMA/pre-SMA may produce therapeutic effect in ADHD through modulating the inhibitory control system.

IPL is an important component of the default mode network (DMN), a network that is highly associated with ADHD. The IPL is divided into angular gyrus and supramarginal gyrus. In the first three pipelines, we observe that IPL is located anterior to P3 or P4, and we classify it as the angular region. However, in the negative part of pipeline3, IPL is situated below P4 and positioned more posteriorly, leading us to classify it as the supramarginal region. Both angular gyrus and supramarginal gyrus play crucial roles in cognitive and emotional processing. Therefore, stimulating IPL may modulate the activity of the DMN and have therapeutic effects on ADHD. Previous systematic reviews have identified the right IPL as a key region for visuospatial attention [58], which is similar to the results of our current subgroup analysis. Additionally, it has been reported that transient virtual lesions of the right, but not the left IPL in the intact human brain can lead to performance declines during attentional reorienting [59, 60]. Our subgroup analysis demonstrated abnormal functional connectivity in the right IPL in both the ADHD-C and ADHD-I types. This result further confirms the role of right IPL in attention, and also provides stronger evidence for its potential use as a NIBS target.

The literature presented offers evidence supporting the utilization of these brain regions in NIBS for ADHD. By stimulating these regions, it is possible to observe varied effects due to the different roles these regions may play in ADHD. These distinct roles can subsequently guide the application of these regions in addressing different symptoms associated with ADHD.

There are several limitations to our study. While we offer numerous possible stimulation sites for NIBS treatment, we cannot accurately predict the specific effects of such stimulation. For example, we are unable to determine whether the stimulation will have an excitatory or inhibitory effect. Another limitation of the present study is that the connectivity analysis only focused on FC. Future studies that combine both anatomical and functional analyses may provide more robust evidence for identifying optimal stimulation sites. Third, The meta-analysis conducted by Neurosynth is not without its limitations. Automatic extraction and synthesis of fMRI activation coordinates may introduce potential errors. However, various supporting analyses have been carried out to validate and assess the sensitivity of Neurosynth-based meta-analysis, which provide evidence for the feasibility of this method [27]. Fourthly, due to the small sample size of ADHD-H type in the databases used, further analysis on patients of this type is not feasible. More patients with this type will be included in subsequent studies for further exploration to increase the generalizability of the results. Finally, we do not currently know which pipeline is optimal for identifying potential NIBS targets for treating ADHD. Each pipeline has its own strengths: pipeline 1 identifies regions directly associated with ADHD pathophysiology, pipeline 2 identifies regions with the strongest correlation to the ADHD network, and pipeline 3 identifies regions that correlate with the largest number of ADHD ROIs. Gaining a comprehensive understanding of these distinct areas may help researchers in selecting target regions during clinical practice.

Conclusion

Conclusively, combining neurosynth-based meta-analysis, RS-FC analysis, and cross-dataset validation, we identified dlPFC, IFG, IPL, and SMA/preSMA and their corresponding scalp location as potential NIBS targets for ADHD. These findings provide new insights for the future application of NIBS in treating ADHD patients.

Responses