Prasinezumab slows motor progression in Parkinsons disease: beyond the clinical data

Introduction

Despite genetic and preclinical evidence supporting pathogenic role of α-synuclein, therapeutic approach targeting the protein has yet to translate into successful clinical outcomes. Prasinezumab, a humanized monoclonal anti-α-synuclein antibody, has been shown to have little effect on total MDS-UPDRS scores and dopamine transporter imaging compared to placebo1. However, a recent post hoc subgroup analysis suggested that it may have a meaningful therapeutic effect (as measured by MDS-UPDRS Part III) in a subset of patients with rapidly progressing disease2.

We need to approach these results with tempered optimism despite the encouraging outcome. First, the post hoc subgroup analyses were carried out in the original study that did not meet most of its endpoints. Post hoc subgroup analyses are known to be susceptible to inflated false positive rates due to multiple statistical tests3. In addition, concerns surrounding the original study, including issues regarding target engagement and outcome selection4, remain unaddressed. Moreover, there are potential underlying factors that could have enhanced the apparent treatment effects in the rapidly progressing subpopulation. There are also confounding factors that may contribute to inconsistency of the results from these clinical trials. Here we highlight some major concerns and provide our perspectives on some of the less explored scientific issues.

Preclinical

Target selection and animal model

There is substantial evidence supporting the pathophysiologic role of α-synuclein in PD pathogenesis, and thus making it the prime therapeutic target. Strategies focused on α-synuclein aggregation present a more compelling rationale than those that aim at entirely eliminating the protein, as endogenous α-synuclein plays crucial physiological roles in neuronal activities, including synaptic vesicle transmission5. The latter strategy is likely justified by the findings that α-synuclein gene knockout in mice did not produce major detrimental effects6. However, the repercussions of α-synuclein removal from the human brain remain unknown, as mice have varied susceptibility to α-synuclein dysregulation. This is evidenced by the fact that most mouse models expressing mutant α-synuclein at physiologically relevant levels only exhibit mild phenotypes. Additionally, abnormalities found in α-synuclein overexpression animal models do not necessarily prove its pathogenicity, as even overexpression of nontoxic green fluorescence protein has led to neurodegeneration in dopaminergic (DA) neurons7. The human and mouse homologs of the SNCA gene share 95% sequence identity. The A53T mutation, where alanine is replaced by threonine, is the first α-synuclein gene mutation identified to be associated with PD. Interestingly, mice naturally possess threonine at the 53rd amino acid position. Human α-synuclein seeds propagate aggregation slower in native mouse proteins, and vice versa, indicating inherent differences across species8. Therefore, mouse models represent a suboptimal system for therapeutic development, especially for the α-synuclein targeting therapies. Non-human primates (NHP) which share close similarities in genetic and physiological predisposition with humans may be a better experimental model. Ideally, this model could incorporate artificial aging9 which may induce molecular and organelle dysfunctions, and related inflammation and oxidative stress, laying the groundwork for neurodegeneration10. Amplified α-synuclein fibrils derived from postmortem brain tissue, which possess bona fide structural characteristics of pathogenic α-synuclein11 and able to induce Lewy pathologies similar to those in human patients12, could be a valuable tool for recapitulating physiologically relevant PD pathology in NHP models. Additionally, human neurons13 or brain organoids14 derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) obtained from PD patients represent complementary platforms, as they may be able to more accurately replicate the detrimental cascades and compensatory mechanisms in patients. However, the microenvironment in culture system may influence the phenotypes, and behavioral recovery cannot be assessed in these cellular/organoid models.

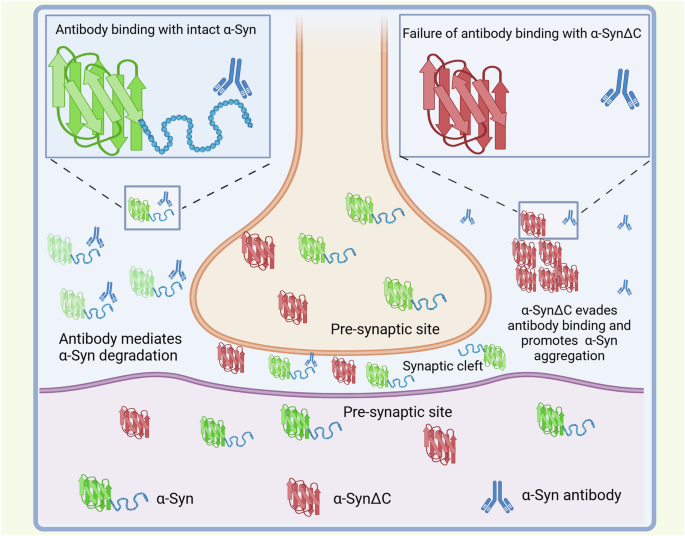

Prasinezumab is the humanized version of mouse monoclonal antibody 9E4 that recognizes amino acids 118–126 of human α-synuclein15. 9E4 has been shown to be able to alleviate α-synuclein-related neuronal pathology, and rescue cognitive and motor deficits by suppressing interneuron transmission of α-synuclein in mouse models15. However, the potential distinct cleavage or other post translational modifications (PTMs) of α-synuclein in human may possibly explain the discordance seen in clinical trial and experimental mouse studies. Accumulating evidence has shown that c-terminus truncated α-synuclein exhibits a much higher propensity for self-assembly of detrimental fibrils compared to full-length or familial PD-related mutant α-synuclein16. Several c-terminus truncated forms of α-synuclein, including 1–103, 1–110 and 1-11517,18, have been identified from the post-mortem brain tissue of PD, which prasinezumab is unable to recognize and mediate its degradation (Fig. 1). Upon antibody administration, the residual c-terminus truncated α-synuclein may not induce immediate detrimental consequences in the mouse model within a short timeframe. However, it may induce significant de novo α-synuclein fibrillation in PD patients during the intervals of antibody administration when the antibody is insufficient to remove the aggregates. Moreover, although human α-synuclein may still be cleaved at its c-terminus in mouse, the truncation is regulated by specific genetic background, such as the human APOE genotype19, indicating that the truncation may be differentially regulated in humans. In addition, α-synuclein undergoes a variety of PTMs which play distinct roles at different stages of pathology development in various neurodegenerative diseases. For instance, nitration of tyrosine 125 of α-synuclein, identified in PD Lewy bodies (LBs), has been demonstrated to significantly affect the dimerization of α-synuclein20. The same amino acid is also subject to dysregulated phosphorylation in PD, which has an impact on α-synuclein oligomerization21. Thus, PD influences the PTMs in α-synuclein, including the epitope region, potentially altering the protein conformation and affecting the efficacy of the antibody that performs well in mice when applied to humans.

C-terminus truncated α-synuclein (α-SynΔC) can evade the antibody binding and promote α-syn aggregation, resulting in neurodegeneration. Antibodies may find it difficult to enter the narrow synaptic cleft where there may be enriched spreading α-syn.

Clinical trials

Target engagement

Experience gained from therapeutic development in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) can provide useful insights. First, a prevailing hypothesis for the lack of success of current therapeutic exploration is that the initiation of treatment (when clinical manifestations are already present) is too late after the pathological cascades have been triggered. This discordance between pathological and clinical changes is supported by the fact that motor symptoms of PD are not clinically evident until 50–60% of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra have been lost22. In addition, α-synuclein pathological changes may begin years before the diagnosis of PD. α-synuclein seed amplification assay (SAA) can detect pathogenic α-synuclein in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of prodromal PD patients23,24,25 and also in blood samples26. These observations are similar in AD, where Aβ deposition occurs long before symptoms become apparent. For instance, Aβ-PET imaging has shown increases in uptake of the Pittsburgh compound B [PiB] tracer up to 10 years before symptom onset in mutation carriers27. The success of monoclonal anti-Aβ antibodies in clinical trials provides evidence that neurodegeneration may be mitigated even after years of Aβ accumulation, raising optimism that delayed initiation of α-synuclein-targeting therapies could similarly attenuate neurodegeneration in PD. Second, there is an argument that the failure of PD therapeutic trials may be due to the insufficiency of drug delivery to the central nervous system (CNS). Antibodies that are delivered intravenously need to pass through the blood–brain barrier (BBB) to reach the brain parenchyma. While the antibodies that bind α-synuclein in the CSF may not represent an accurate indicator of target engagement in the brain, antibody concentration in the CSF can still provide a clue of the drug delivery efficiency. CSF-to-serum ratio of prasinezumab was approximately 0.3%28, which is comparable to that of lecanemab29, a recently approved monoclonal antibody in AD. Lecanemab is capable of effectively removing the Aβ plaque in the brain, suggesting that the delivery across BBB might not be the most critical hurdle that compromises the efficacy of prasinezumab. However, monoclonal anti-Aβ antibody targets a more accessible substrate (extracellular Aβ plaques). In contrast, no other monoclonal antibody targeting intracellular aggregates in neurodegeneration has seen clinical success, including antibodies against Tau, or huntingtin protein. Thus, intracellular delivery of α-synuclein antibody may be the key challenge in pharmacokinetics.

Even though the antibody may target extracellular α-synuclein to impede its spreading, the proportion of extracellular α- synuclein accessible to the antibody is unknown. α- synuclein may be transmitted between the neurons primarily through synaptic contacts, given the enrichment of α- synuclein in the presynaptic region, and its critical roles in presynaptic and postsynaptic sites30. To ensure efficient neurotransmitter reuptake, synaptic contacts are in close proximity (synaptic cleft distance is 20–30 nm) and it’s unknown how much antibody that passes through BBB is able to enter synaptic clefts to bind the spreading α-synuclein. Exosomes have been demonstrated to encapsulate α- synuclein to mediate its spreading, and it is unclear how this affects the target binding of the antibody. Interestingly, it has also been reported that CSF α-synuclein decreased in the early stage of PD, and its level did not correlate with the disease progression31. Therefore, it is still unknown if further removal of the already decreased extracellular α-synuclein would be beneficial. In addition, α-synuclein filaments extracted from the PD and MSA brains exhibit different conformation and biochemical features32, which potentially affect the recognition and binding of the antibody to the distinct pathogenic α-synuclein in these two diseases.

Patient stratification (heterogeneity) and biomarker

The rate of disease progression is determined by various underlying mechanisms, which could respond differently to monoclonal anti-α-synuclein antibodies. Individuals experiencing rapid progression may harbor more severe α-synuclein pathology, the propagation of which is widely recognized as the primary driver of PD advancement33, and thus more responsive to monoclonal anti-α-synuclein antibodies. In contrast, slower progression in PD may be attributable to other factors, such as LRRK2 G2019S mutation, which has been linked to a slower decline in motor UPDRS scores34. A greater progression may enhance the likelihood of identifying a potential effect, but the positive outcomes in those who progressed rapidly may be because this group is more pathophysiologically homogeneous. With the establishment of seed amplification assay (SAA) as a reliable method to detect pathogenic α-synuclein in patients23,25,35,36, it will be useful to stratify randomized trial subjects based on their SAA status. Importantly, SAA using CSF samples potentially reflects the Lewy pathology in the brains of PD patients. In the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI) cohort, the overall sensitivity of CSF α-synuclein SAA for detecting PD was 87·7% (95% CI 84·9–90·5), and the assay was positive in 67.5% (95% CI 59.2–75.8) of LRRK2 PD cases and 95.9% (95% CI 90.4–100) in GBA PD cases. Interestingly, previous neuropathological studies have reported similar prevalence of LBs in patients. Among the clinically diagnosed PD cases over a 3-year period in the United Kingdom Parkinson’s Disease Society (UKPDS) brain bank, 76 out of 100 (76%) patients were found to have Lewy pathology37. In another independent study, Lewy pathology was identified in 28 out of 43 cases (65%) of idiopathic PD38. LRRK2 and GBA appear to have differing impact on the Lewy pathology in postmortem studies. In a large neuropathological study, widespread alpha-synuclein pathology were observed in all GBA mutation carriers with PD39. Another study involving 943 Lewy body disease cases found that GBA variants were associated with more extensive Lewy pathology compared to controls40. In contrast, only 17 out of 37 (45.9%) LRRK2-related PD cases were found to have Lewy pathology in postmortem studies41. Future trials could include SAA status as an outcome if we are able to standardize SAA to provide quantified levels of pathogenic α-synuclein. However, there are limitations of SAA to reflect the disease severity, as even LBs (containing pathogenic α-synuclein) are not present in all PD cases38, with no correlations of LBs with the motor symptoms. LB counts have been shown to be significantly higher among the PD patients with dementia compared with the PD subjects without dementia in the brain42. In LRRK2-related PD, nonmotor symptoms are more correlated to the LB pathology than motor symptoms, with tremor symptom surprisingly being associated with the absence of LBs. In addition to LRRK2 and other genetic factors, including APOE status43, GBA40 and PRKN44 gene mutations, LB pathology may be influenced by many factors, including individual variability. Widespread LBs can be detected even in the brains of healthy aged subjects45, although the significance is unknown. In addition, SAA measurement does not adequately differentiate pathogenic α-synuclein isolated from different synucleinopathies. It is also unclear how α-synuclein crosses the BBB to reach CSF, where it could be collected and used for SAA. The integrity of BBB is compromised in PD46 and the extent of such disruption, which may not be consistent with the disease severity, would undoubtedly affect the presence of pathogenic α-synuclein in CSF.

PD is heterogeneous, not only in its clinical manifestations, but also in its underlying pathophysiology. Patients with PD caused by pathophysiological mechanisms unrelated to or less influenced by the α-synuclein cascade may not respond well to α-synuclein-targeting therapies, potentially affecting the clinical outcomes in the trials. A similar phenomenon was seen in the donanemab clinical trial for AD. In this study, participants in the low/medium tau group demonstrated significant clinical benefits, with stable cognitive (CDR-SB) scores observed at the 1-year mark. Conversely, this effect was not observed in the high tau group47. Hence, pathogenic heterogeneity may represent a primary factor accounting for the potential type 2 errors in the clinical trials of therapeutic options in neurodegenerative diseases. To better stratify the patients according to its pathophysiologic features in clinical trials for PD, biomarkers reflecting common pathological causal factors other than α-synuclein should be included. Some forms of PD may be free of or with less involvement of α-synuclein pathology, such as PRKN- or LRRK2-related PD. Recently, LRRK2 kinase-mediated centrosomal alterations were shown to be present in lymphoblastoid cell lines from LRRK2 PD patients and non-manifesting LRRK2 mutation carriers, as well as a subset (around 30%) of idiopathic PD patients48, suggesting that LRRK2-related biomarker may identify a common pathological abnormality in general PD, though LRRK2 variants were only identified in around 3% PD population49. The centrosomal alterations could be rescued by LRRK2 inhibitors, suggesting that this subset of idiopathic PD patients may benefit more from LRRK2-targeting therapeutics comparing with the one targeting α-synuclein. GBA gene mutation is another primary risk factor in idiopathic PD. Although PD patients carrying GBA mutations have a more diffused LB pathology, it is unknown how GBA mutations affect the biochemical features of pathogenic α-synuclein and its recognition and binding by the antibody. Therefore, targeting α-synuclein without dealing with GBA abnormality may not achieve optimal therapeutic outcome in GBA-related PD. It is advisable to pre-stratify this group of patients for potential post hoc study in the future. If the clinical trial of anti-α-synuclein antibody is carried out to include subjects from Asia or other underrepresented geographical regions, PRKN genetic screening should be conducted, as its mutations/variants are frequent among Asians, and it will be interesting to determine if the antibody will work in the subsets of PD without or with less LB pathology. Surprisingly, a recent study shows positive SAA results in over half of the PD patients with PRKN variants using neuron-derived extracellular vesicles from blood50. Thus, a positive SAA result may not rule out the involvement of PRKN in the pathogenesis of PD. In addition, the number of biomarkers to be included in clinical trial to stratify patients should be limited to avoid reduced statistical power due to small sample size in the subgroups and increased risk of type 2 errors. Excessive stratification by biomarkers may also lead to lack of generalizability for the clinical trial results.

Adverse effects

Adverse events of prasinezumab have been less discussed since the trial results were released, probably owing to comparable incidence rates between the placebo group and the treatment groups. However, it is worth noting that one death (by suicide) occurred 26 days after the first dose of 1500 mg prasinezumab in part 2 of the clinical trial, although it was not deemed as adverse event that resulted from the immunotherapy. Additionally, there was a suicide attempt in the group of 4500 mg in part 11. Given the small sample size, the suicidal events are likely to be outliers, or they are coincidental. A meta-analysis in 500,000 patients with PD found that 1.25% of them had suicidal behavior51. While it is speculative to associate suicide behavior with the use of prasinezumab, closer monitoring will be needed given that these events occurred within two years of the trial, or within one year of the treatment being started. Clinical trial participants are usually more curious and less anxious and socially distressed52. Also of note is that another two patients receiving the prasinezumab experienced worsening of PD symptoms. This worsening and other problems in the treatment groups were not present in the placebo group, suggesting that the monoclonal antibody may have unknown potential adverse effects on the nervous system. The mechanism may involve the immune response, as the elimination of the α-synuclein aggregates is achieved through the host immune system, which also contributes to PD pathogenesis if aberrantly activated. Although anti-drug antibody against the therapeutic monoclonal antibody was not detected in the previous clinical trial28, there could be other forms of immune response, including pro-inflammatory cytokine production. Immunoglobulin G isolated from PD patients could trigger inflammation and selective DA neuronal death in rat substantia nigra53. Alternatively, moderate immune response that may be tolerated in healthy subjects could induce pathological effects on the susceptible PD subjects with compromised BBB, impaired neurons and activated microglial cells. If the spectrum of the adverse events overlaps with the existing PD clinical symptoms, it will be harder to establish the association of the adverse events with the antibody. Previous studies found increased inflammatory cytokines and microgliosis in those who attempted suicide or committed suicide, suggesting that neuroinflammation is associated with suicide54. In AD, anti-amyloid antibodies engage perivascular Aβ deposits, inducing inflammation and amyloid related imaging abnormalities (ARIAs) which could sometimes be fatal55. An important question that should be addressed is the extent to which the neural inflammation induced by the monoclonal antibody may counteract the benefit of eliminating pathogenic α-synuclein. MRI techniques, including diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences can help detect inflammation and changes in tissue integrity. PET imaging with radiotracers targeting specific immune markers, such as translocator protein (TSPO), can assess microglial activation and neuroinflammation in the brain. These methods have been utilized to monitor microglial activation and neuroinflammation for other therapeutic studies in PD56.

Statistical analysis

In the post hoc study, the subjects with more rapid progression PD were selected to compare the drug effects2. However, the subjects had more similar UPDRS Part III scores compared with the original cohort in which heterogeneity in progression led to larger variety of UPDRS Part III scores. Thus, the data variability of motor symptoms decreased and the power of detecting the differences between the groups increased. We eagerly await the findings of PADOVA, a comparable phase 2 clinical trial of prasinezumab, which features nearly double the sample size and study duration, and utilizes time to a confirmed motor progression event (4.63 points in Movement Disorders Society Sponsored Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) Motor Examination57) as its primary outcome measure. To detect the true effect of prasinezumab, the ongoing clinical trial extended the duration of the study to allow for more significant changes in UPDRS Part III (effect sizes). The extended duration, however, may also allow increased differences of UPDRS Part III within the same group (variability of the data) due to heterogeneity in progression. Since both effect sizes and variability of the data contribute to statistic power, it is unknown which factor, caused by extended trial duration, will have a greater impact on the statistical power. The confirmed motor progression event does represent a clinically meaningful change. However, from the practical perspective, it is not clear what p-value should be set to enable the detection of a difference that can have a socioeconomic impact so as to justify its potential clinical application.

Combination therapy

Combination therapies have been widely used for common conditions such as hypertension and diabetes. Trials using compounds that act on different targets may be an attractive proposition in PD, but unless we are able to characterize and measure the individual drug effects, it will be difficult to draw definitive conclusions on the efficacy of combination therapy. Selection of patients based on homogeneous pathophysiologic features will increase the chance of success, especially if the effect size is relatively small. For α-synuclein targeted therapy, clinical trials should include patients who have clearly defined profiles with measurable synuclein abnormalities and exclude those whose pathophysiologic mechanisms are complicated by other pathogenic factors. Once we have developed individual therapeutic options, we can tailor the combination therapy to achieve personal medicine with the guidance of biomarkers that are reflective of the underlying pathophysiologic signatures in PD. However, combination therapy for PD remains a future prospect. A deeper understanding of the primary causal target(s) and their specific interactions within pathophysiological pathways is essential to identify and develop the optimal combination therapies.

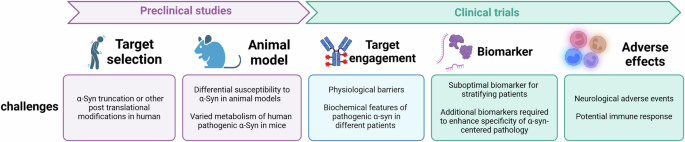

In summary, antibody-based immunotherapy in PD certainly holds promise, even though it is important to recognize that we are still in exploratory phases. Mismatched expectations sometimes can lead to hasty decisions from both the funders and clinical community, which may derail future efforts. As we get to learn more from present and past experiences (Fig. 2), we will be able to better optimize preclinical research to address specific challenges and to improve clinical trial methodology involving carefully selected patients. This will facilitate the detection of clinically meaningful outcomes while at the same time keeping close vigilance on its safety profile.

Critical challenges exist throughout the therapeutic development process, from preclinical studies to clinical trials, including target selection, appropriate animal models, target engagement validation, biomarker identification, and the assessment of adverse effects. A flaw at any stage can undermine the entire development process, highlighting the need for meticulous consideration to ensure the safety and efficacy of the therapeutic candidate, as well as the complexity and risks inherent in drug development.

Responses