Preclinical assessment of a ganglioside-targeted therapy for Parkinson’s disease with the first-in-class adaptive peptide AmyP53

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurological disorder which affects both the central and peripheral nervous systems. It is characterized by a progressive loss of nigrostriatal dopamine neurons and is associated with a broad spectrum of motor and non-motor symptoms1. PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease after Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and its prevalence will continue to grow exponentially as the population ages2. The burden of PD could exceed 17 million people worldwide by 20402,3.

Despite significant efforts, there are no disease-modifying treatments addressing the root causes of PD and its primary development4,5. The current therapeutic for PD patients is centered on the dopaminergic system, according to the typical loss of dopaminergic neurons in this disease6. However, dopamine-based drugs do not block nor even slow down disease progression7. Clearly, there is an urgent need for innovative therapies that tackle the root causes of PD. In this respect, α-synuclein induced neurotoxicity is the most promising target, based on a wide range of proofs that identify this protein as the principal culprit in PD and related diseases referred to as synucleopathies8,9,10. α-synuclein is a 14.5 kDa proteinwith lipid-binding properties11. It is expressed in the brain and chiefly located in synaptic terminals12. Its main physiological function is generally thought to mediate vesicular trafficking at the neuronal membrane13, control synaptic plasticity and regulate neurotransmitter release14. Extracellular α-synuclein15 can also bind to the plasma membrane of brain cells and then self-assemble into neurotoxic oligomers16,17,18. Correspondingly, the oligomerization of α-synuclein in the plasma membrane of brain cells is considered as a primary cause of PD18. Indeed, membrane-associated α-synuclein oligomers (amyloid pores)19,20 trigger a cascade of neurotoxicity events involving dysregulated Ca2+ influx and eventually the loss of dopaminergic neurons that are involved in motor process control, a hallmark of PD.

Conceptually, it seems easy to neutralize α-synuclein, but the task proved to be more challenging than anticipated. α-synuclein belongs to the category of proteins called intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) that can adopt myriads of distinct conformations in solution21,22,23,24. However, when bound to the membrane, the protein typically adopts an α-helical conformation25, which is the starting point of the oligomerization process into Ca2+ permeable amyloid pores18. Indeed, IDP’s toxicity has been associated with the ability of these proteins to bind to biological membranes26 and induce membrane damage27,28,29.

Membrane lipids, especially gangliosides and cholesterol, play a critical role in amyloid pore formation which occurs in lipid rafts30. In fact, gangliosides act as molecular chaperones able to convert a disordered extracellular α-synuclein into a structured protein31 displaying a functional ganglioside binding domain (amino acids 34–45)32 surrounded by two α-helix domains, one of which includes a cholesterol binding domain (amino acids 67–78)33. Then, the protein penetrates the membrane, interacts with cholesterol and oligomerizes into amyloid pores through a cholesterol-controlled mechanism34,35. Because they mediate a dysregulated entry of Ca2+ ions in target cells, amyloid pores can be considered as the root cause of PD and a privileged target for innovative therapies18. One possible approach is to block the initial binding of α-synuclein monomers to plasma membrane gangliosides. However, there are two pitfalls in this strategy. (i) As other amyloid proteins such as Alzheimer’s β-amyloid protein (Aβ), α-synuclein does not bind to a single ganglioside molecule but rather selects a cluster of gangliosides with a high dynamic at the edge of lipid rafts36. In other words, the target of α-synuclein is not stable but in motion. (ii) As a typical IDP, α-synuclein undergoes a gradual structuration upon binding to gangliosides, meaning that membranes act as a catalyst for the formation of neurotoxic oligomers37,38. This striking property must be considered for the development of a blocking therapeutic compound. This definitely excludes small organic compounds, usually polycyclic, which are far too rigid and locked in a stable conformation18,39. To overcome this problem, we designed a synthetic peptide derived from the common ganglioside binding domain of α-synuclein and Aβ40. This peptide, called AmyP53, displays striking structural adaptive properties. It is specific enough to ignore neutral glycolipids while sufficiently plastic to interact with the main ganglioside species expressed in human brain (GM1, GM3, GD1a, GD1b, GT1b) that are recognized (yet with distinct specificities) by Aβ41,42 and α-synuclein32,43,44,45,46. The therapeutic effect and mechanism of action of AmyP53 in AD models have been recently published by our group36,47,48. Here we present parallel data on the molecular mechanism of action and the therapeutic efficiency of AmyP53 in several PD models. These new data confirm the unique therapeutic potential of AmyP53 and further demonstrate that it is applicable to PD.

Results

Interaction of AmyP53 and α-synuclein with GT1b ganglioside

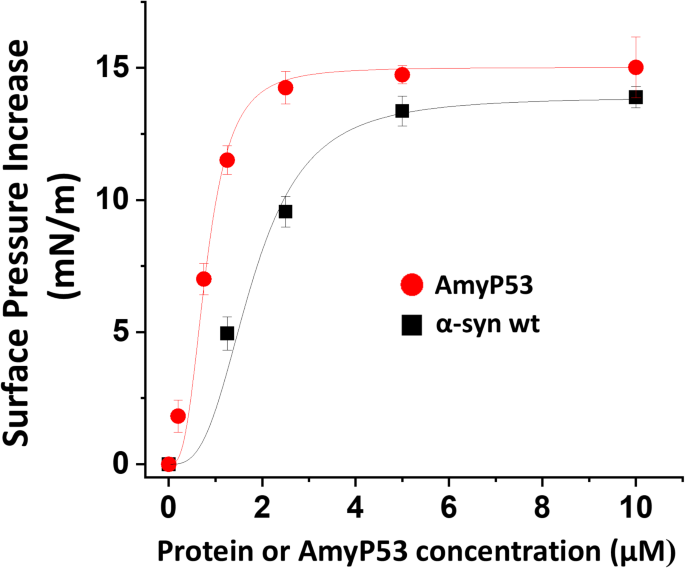

Previous studies have shown that α-synuclein interacts with brain gangliosides, including GM1, GM3 and GT1b32,43. In the present study, we selected GT1b because this ganglioside can form (i) stable monolayers that are compatible with microtensiometry measurements and (ii) micellar solutions that are compatible with circular dichroism analysis49. First, we studied the interaction of wild-type α-synuclein and AmyP53 with reconstituted monolayers of GT1b. In these experiments, the protein-ganglioside interaction is detected by an increase of the surface pressure measured by a microtensiometer at the air-water interface. The data indicated that AmyP53 interacts with the gangliosides at concentrations significantly lower than wild-type α-synuclein (Fig. 1). The logistic curve fitting allowed to estimate the EC50 (concentration that gives half-maximal response) for AmyP53 at 0.52 ± 0.08 µM compared with 1.78 µM ± 0.15 µM for wild-type α-synuclein. As shown in Table 1, mutant α-synucleins also recognized the ganglioside membrane, yet with distinct characteristics. The EC50values were statistically significant between AmyP53 and all α-synuclein proteins, and between wild-type and mutant α-synucleins. Overall, these experiments confirmed the higher avidity of AmyP53 for the ganglioside membrane compared with wild-type and mutant forms of α-synuclein.

Interaction of wild-type α-synuclein proteins and AmyP53 with GT1b ganglioside monolayers. Monolayers of ganglioside GT1b were prepared at the air-interface at an initial surface pressure of 17.5 mN/m. After equilibrium, wild-type (wt) or or AmyP53 was added in the aqueous subphase underneath the monolayer at the indicated concentrations. Surface pressure measurements were recorded in real-time until reaching a plateau value, typically after 1 h of incubation. The values correspond to the maximal surface pressure increase measured when the system has reached a state of equilibrium. The data are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments. A logistic fit was applied to each curve.

AmyP53 is a competitive inhibitor of α-synuclein binding to ganglioside GT1b

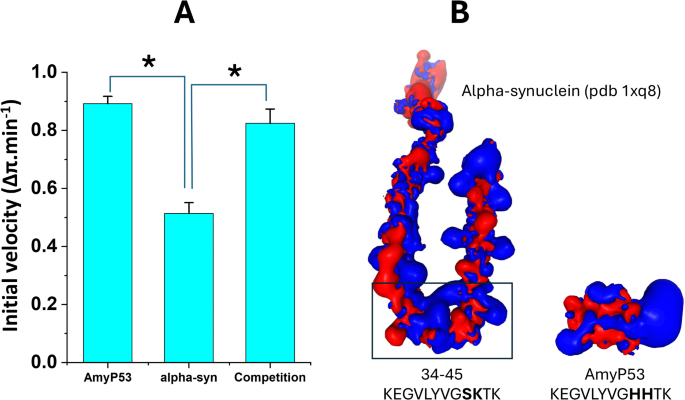

In addition to being able to recognize GT1b monolayers at a lower concentration than α-synucleins, AmyP53 also interacts with these monolayers faster than these proteins. The initial velocity of AmyP53 for GT1b binding is 0.89 ± 0.03 Δπ.min−1, compared with 0.51 ± 0.04 Δπ.min−1 for wild-type α-synuclein (Fig. 2A). When both AmyP53 and α-synuclein were added simultaneously to the GT1b monolayer, the kinetics of interaction was similar to that of AmyP53, with an initial velocity of 0.82 ± 0.05 Δπ.min−1. These data indicate that AmyP53 wins the race for the occupation of a GT1b raft-like membrane when present in competition with α-synuclein. Figure 2B shows the electrostatic surface potential of α-synuclein, especially the 34–45 fragment which shares 10 on 12 amino acids with AmyP5340. It can be observed that AmyP53 is globally more electropositive than the 34–45 motif of α-syn. This unique feature gives a kinetic advantage allowing AmyP53 to reach the electronegative surface of raft gangliosides faster than α-synuclein. Its short size may also help speed up the diffusion rate of AmyP53. Both effects may explain why AmyP53 wins the binding competition for lipid rafts.

AmyP53 is a competitive inhibitor of α-synuclein binding to ganglioside GT1b. (A) The values of the histograms are indicated as the mean ± SD (p < 0.05 between AmyP53 and α-synuclein, no statistically significant difference between AmyP53 and AmyP53/α-synuclein competition in the Student’s t-test). (B) Electrostatic surface potential of α-synuclein (from pdb 1qx8), and AmyP53 (blue, electropositive; red, electronegative). The position of amino acid residues 34–45 in full length α-synuclein is indicated by a rectangle. The amino acid sequences of AmyP53 and α-synuclein fragment 34–45 are indicated.

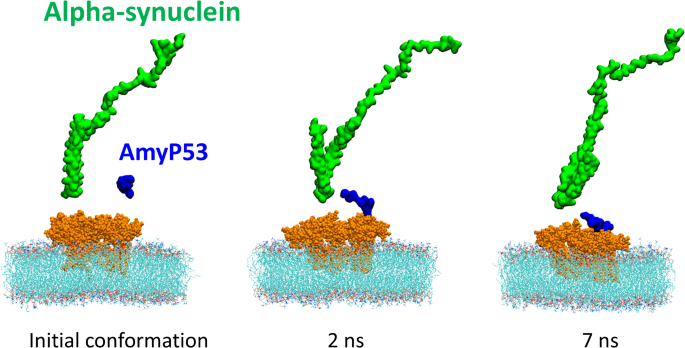

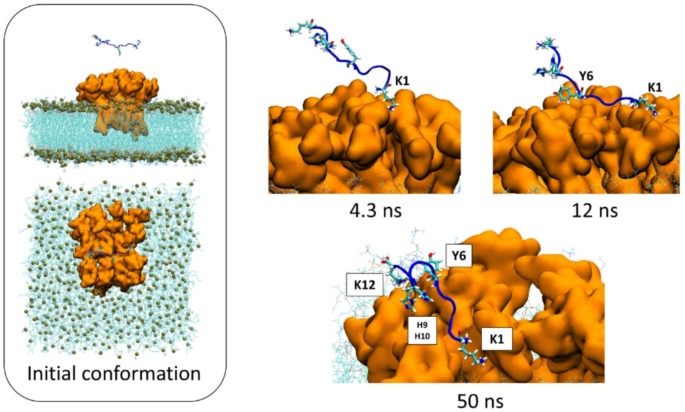

Then we used molecular dynamics simulations to evaluate how fast AmyP53 interacts on the surface of a lipid raft compared to α-synuclein. The initial conformation presented in Fig. 3 shows that α-synuclein and AmyP53 are placed at a similar height above the polar part of GT1b molecules. Only 2 ns of simulation were sufficient to observe the first contact between AmyP53 and the sugar moiety of GT1b molecules while α-synuclein barely moved along the z axis. Then, AmyP53 extensively interacts with the lipid raft after 7 ns of simulation.

Competition between α-synuclein and AmyP53 to interact with the polar surface of the lipid raft. α-synuclein is depicted as green surface, AmyP53 is depicted as blue surface, gangliosides are depicted as orange spheres and POPC are depicted as thin lines colored by atom names (carbon in cyan, hydrogen in white, oxygen in red, nitrogen in blue and phosphorus in brown).

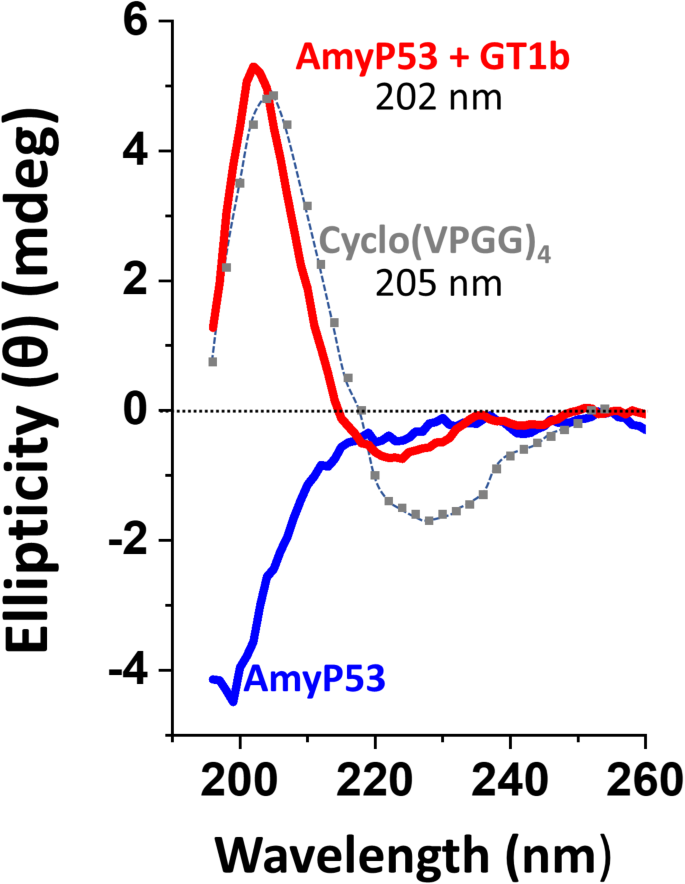

AmyP53 structuration upon GT1b binding

AmyP53 is 12-mer peptide designed by combining the ganglioside-binding domains of α-synuclein and Aβ. This peptide is highly soluble in water (up to 150 mM)47. We performed a circular dichroism (CD) analysis to determine whether AmyP53 adopts a stable conformation in solution. The CD spectrum of AmyP53 in water solution does not reveal any specific structure; no α-helix, no β-turn (Fig. 4, blue spectrum). Thus, AmyP53 can be considered as a disordered peptide. However, in presence of GT1b micelles, the peptide undergoes a typical β-turn conformation demonstrated by the presence of a positive band at 202 nm and a negative band at 224 nm, (Fig. 4, red spectrum). For comparison we showed the circular dichroism spectrum of the Cyclo(VPGG)4 peptide, which is a reference for β-turn identification by circular dichroism50. These data, which confirmed that AmyP53 physically interacts with GT1b, showed that AmyP53 adopts a turn conformation in presence of GT1b. Molecular dynamics simulations fully confirmed this conformational adaptation (Fig. 5). Under initial conditions, a disordered conformer of AmyP53 is placed above the central area of the raft. Very rapidly, the N-terminal amino acid K1 dives into the raft, initiating the interaction. In subsequent steps, the peptide first adopts a broken conformation (at 12 ns), then migrates to the periphery of the raft and adopts a typical turn conformation (at 50 ns). Our in-silico data also allowed to identify the key amino acid residues involved in AmyP53 binding to GT1b, i.e. K1, Y6, H9 and K12.

Circular dichroism analysis of AmyP53 structuration upon GT1b binding. AmyP53 was tested in absence (blue curve) or in presence (red curve) of GT1b micelles. The spectrum of Cyclo(VPGG)4, a β-turn reference, is colored in grey. Note that AmyP53 (in presence of GT1b) and the reference have a similar peak at 202 and 205 nm, respectively.

Conformational flexibility of AmyP53 during its interaction with a GT1b raft. The initial conditions of the system are shown in the left panel. A disordered conformer of AmyP53 is placed above the central area of the raft. The snapshots illustrate how AmyP53 changes its conformation to dive into to the raft at its N-terminal amino acid K1 (4.3 ns). At 12 ns, it adopts a kinked conformation allowing the amino acids K1 to Y6 to spread on the raft surface. At 50 ns AmyP53 migrated to the periphery of the raft while adopting a typical turn conformation.

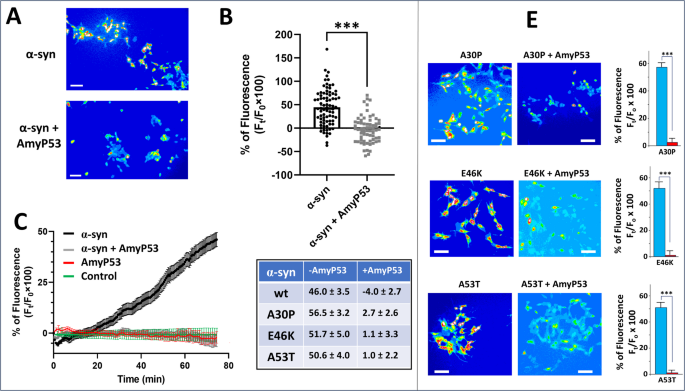

AmyP53 blocks the formation of Ca2+ permeable amyloid pores formed by α-synuclein oligomers in aged brain cells

Then we evaluated the protective effect of AmyP53 in late passage SH-SY5Y cells which mimic aged brain cells36. The cells were loaded with the permeant fluorescent dye Fluo-4AM which labelled the intracellular calcium, then incubated with α-synuclein with or without AmyP53. Amyloid pores formed by the oligomerization of α-synuclein are functionally detected by measuring the intracellular concentration of Ca2+ ions visualized by increased intensity of the Fluo-4AM labelling. As shown in Fig. 6A, a massive entry of calcium was detected in the cells incubated with α-synuclein. In contrast, the cells incubated with the α-synuclein/AmyP53 mixture have a stable and low calcium level. The statistical analysis of these data confirmed the protective effect of AmyP53 in this cellular model of PD (Fig. 6B). The kinetics of Ca2+ entry in cells incubated with α-synuclein alone or with the α-synuclein/AmyP53 mixture showed that the protective effects of AmyP53 against formation of amyloid pores were observed at any time during the 75-min of the assay (Fig. 6C). A control experiment without any treatment confirmed that the baseline is stable during the recordings. Most importantly, AmyP53 by itself did not affect intracellular Ca2+ levels (Fig. 6C). Thus, its efficacy to prevent the increase of intracellular Ca2+ induced by α-synuclein can be attributed to its capacity to block the formation of Ca2+-permeable α-synuclein oligomers in the plasma membrane of aged brain cells. Finally, we tested the capacity of AmyP53 to prevent the formation of such oligomeric pores by mutant forms of α-synuclein (A30P, E46K, A53T) in the same model of aged brain cells (Fig. 6D). All three α-synuclein mutant proteins readily induced an increase of intracellular Ca2+ that could be detected by Ca2+ imaging with Fluo-4AM labelling. Interestingly, A30P was the most effective compared with the wild-type and the two other mutant forms of α-synuclein (Fig. 6, inset). In all cases, AmyP53, used in competition at equimolar concentrations, abrogated the effect for all mutants. Taken together, these data demonstrate that AmyP53 has broad anti-oligomer properties that affect amyloid pore formation induced by both wild-type and mutant α-synuclein proteins.

AmyP53 prevents the formation of Ca2+ permeable amyloid pores by wild-type and mutant forms of α-synuclein. (A) Aged SH-SY5Y cells (> 10 passages in culture) were loaded with the Ca2 + indicator Fluo-4 AM and then incubated with 220 nM of α-synuclein with or without 220 nM AmyP53 as indicated. The micrographs taken after 75 min of incubation showed that the increase in intracellular Ca2+ induced by α-synuclein (warm colors, yellow/red) was strongly inhibited by AmyP53 (cold colors, blue). Scale bars: 100 µm. (B) Student’s t-test was used to compare the statistical significance on calcium dependent fluorescence after α-synuclein treatment between control and AmyP53 conditions (p < 0.001). (C) Kinetics of Ca2+ fluxes induced by α-synuclein (220 nM) in absence (black curve) or presence of AmyP53 (220 nM) (grey curve). Control experiments with AmyP53 (220 nM) alone (red curve) or without any treatment (green curve) are shown for comparison (± SEM, n = 110 cells). (D) Cells incubated with mutant proteins alone, respectively A30P, E46K, and A53T (220 nM), or incubated with both mutant proteins and chimeric peptide (both 220 nM), respectively A30P + AmyP53, E46K + AmyP53, and A53T + AmyP53). The micrographs taken after 75 min of incubation showed that the increase in intracellular Ca2+ induced by mutant forms of α-synuclein (warm colors, yellow/red) was strongly inhibited by AmyP53 (cold colors, blue). Scale bars: 100 μm. Student’s t-test was used to compare the statistical significance on calcium dependent fluorescence after each mutant α-synuclein treatment between control and AmyP53 conditions (p < 0.001). A table summarizing the inhibitory effect of AmyP53 on Ca2+ fluxes induced by wild-type and mutant forms of α-synuclein (expressed as mean ± SEM, all experiments performed in triplicate) is shown in inset.

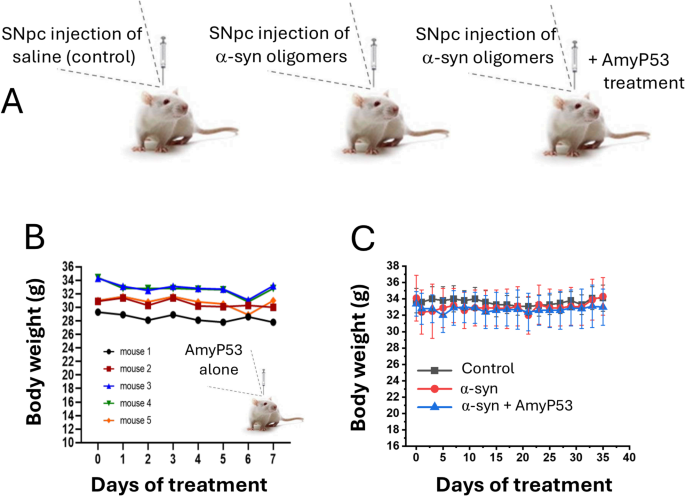

Therapeutic efficiency of AmyP53 in an animal α-synuclein injection model of PD

Finally, a study (Fig. 7A) was designed to investigate the therapeutic effects of AmyP53 in an aged mouse model of PD induced by stereotaxic injection of α-synuclein protofibrils (containing at least 50% of oligomers as detailed in Materials and Methods) into the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc)51. This model reproduces the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the nigra striata area that is an essential neuropathological feature of PD.

Assessment of AmyP53 safety in mice. (A) Experimental protocol. Three groups of 7 animals were studied: control (injection with vehicle), treated with α-synuclein protofibrils, treated with both α-synuclein protofibrils and AmyP53. AmyP53 was then injected intranasally daily in the third group for 35 days. (B) Preliminary assessment of the effect of intracerebroventricular injection of AmyP53 alone followed by 7-day intranasal treatment on mouse body weight (the data show the body weight of each animal separately). There is no statistically significant body weight variation for any animal treated with AmyP53 (Student’s t-test, p < 0.05). (C) Lack of significant variations in body weight between the three groups of animals during the experiment (35 days). Data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 7.

A preliminary assessment of the safety of AmyP53 injection into the SNpc was carefully conducted on 5 mice (Fig. 7B) before starting the complete experimental study which involved 7 mice per group. Administration of AmyP53 followed the design planned for α-synuclein-treated mice. AmyP53 was given intranasally, and 10 min after this administration, mice were subjected to stereotaxic surgery to inject AmyP53 in the SNpc. Mice were then treated with AmyP53 for 7 consecutive days (intra-nasal administration daily). Recovery from surgery was good and mice behaved normally during the whole experiment. Body mass was also stable (Fig. 7B). Altogether, the results of this preliminary step indicated that AmyP53 is safe.

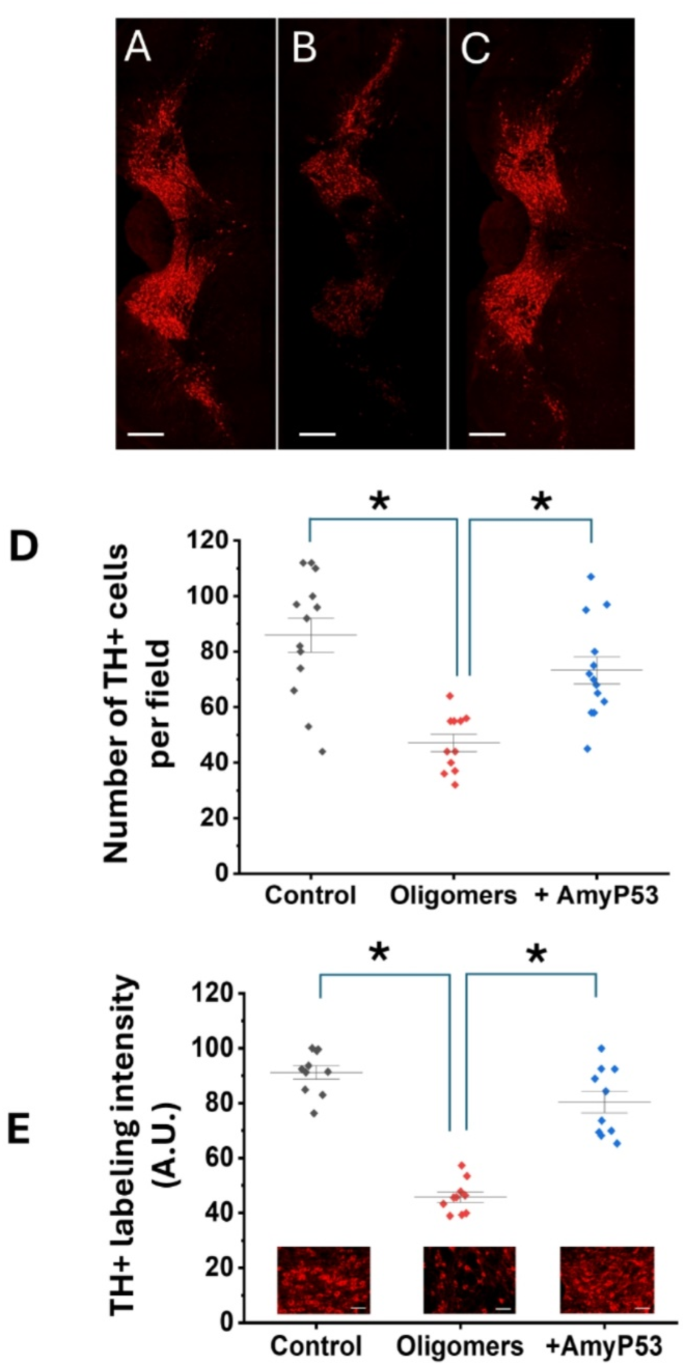

Based on these safety results, we proceeded with the whole experiment which started with the injection of α-synuclein protofibrils into the SNpc and ended with the analysis of dopaminergic neurons after 35 days. Three groups of 7 animals were studied: (i) one group injected with vehicle alone, (ii) one group injected with α-synuclein protofibrils, and (iii) one group co-treated with α-synuclein protofibrils and AmyP53 (an intracerebral administration of AmyP53 co-injected with α-synuclein protofibrils was followed by daily treatment by the intranasal route). Under these conditions, AmyP53 did not display any significant effect on the body weight of the treated mice (Fig. 7C) and did not induce any negative impact on their overall behavior, throughout the 35-day treatment period. At the end of the treatment, animals were euthanized, brains were extracted, fixed, and labelled for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) present in dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 8). While a strong TH signal is observed in the control group (Fig. 8A), α-synuclein injection significantly decreased the immunolabeling of dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 8B). This phenotype is representative of the loss of dopaminergic neurons. AmyP53 induced a protective effect on dopaminergic neurons as demonstrated by the analysis of TH + cells in brain slices from animals exposed to α-synuclein protofibrils and treated with AmyP53 (Fig. 8C). Direct comparison between α-synuclein-treated mice with or without AmyP53 treatment indicated a statistically beneficial effect of AmyP53 on the survival of dopaminergic neurons at day 35 (Fig. 8D, E). This effect was observed by counting the number of TH + neurons (Fig. 8D) and by measuring the intensity of TH immunolabeling (Fig. 8D) in representative microscopic fields.

AmyP53 is active against the loss of dopaminergic neurons induced by α-synuclein protofibrils injected into the brain of aged living mice. AmyP53 rescues dopaminergic neurons loss induced by α-synuclein protofibrils at day 35 after model induction. (A–C) Representative TH immunolabeling of similar brain slices from animals treated with vehicle alone (A), α-synuclein protofibrils (B) and both α-synuclein protofibrils and AmyP53 (C) are shown. Scale bars: 400 μm. (D) Number of TH+ (dopaminergic neurons) at day 35 in the three experimental conditions (control, i.e. vehicle), oligomers (α-synuclein protofibrils) and + AmyP53 (injection of α-synuclein protofibrils in presence of AmyP53, then daily intranasal treatment by AmyP53). (E) The intensity of TH labeling was measured in distinct representative microscopic fields of similar slices at the same magnification. In (D) and (E) the data are expressed as mean ± SD (p < 0.05 between control/oligomers and oligomers/AmyP53 conditions in One-Way ANOVA test and post-hoc analysis). In (E) the micrographs show representative similar fields of TH immunolabeling of brain slices from animals treated with vehicle alone (control), α-synuclein protofibrils (oligomers) and both α-synuclein protofibrils and AmyP53 (+ AmyP53) are shown. Scale bars: 50 μm.

Primary observation (Irwin) test in rodents does not reveal any effect of AmyP53 on behavior and physiological function

Considering that AmyP53 has no effect by itself on intracellular Ca2+ levels (Fig. 6C), the protective effect demonstrated in a rodent model of PD (Fig. 8) suggests that the peptide acts by blocking the neurotoxic cascade induced by α-synuclein oligomers. However, it was important to ensure that the peptide did not cause any physiological changes at the brain level. Thus, we evaluated the potential effects of AmyP53 on brain functions by the primary observation test (Irwin Test)52. Behavioral modifications, physiological and neurotoxicity symptoms, rectal temperature and pupil dilation or contraction were recorded according to a standardized observation grid derived from that of Irwin observation time-points (15 min, 30 min and 1, 2, 4, 6 h and 24 h after intranasal administration of AmyP53 at 0.1, 1.0 and 5.0 mg/kg body weight). Treatment with AmyP53 (6 rats) did not produce any significant effect on the primary observation Irwin test (Table 2). These data showed that AmyP53 has no effect by itself on neurobehavioral functions associated with excitation, sedation, stereotypy, motor-coordination, autonomic and pain. Thus, its protective effect on the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the animal model of PD (Fig. 8) can be attributed to its ability to block the neurotoxic cascade induced by α-synuclein oligomers.

Preclinical studies of AmyP53 further demonstrate its total safety in two animal models

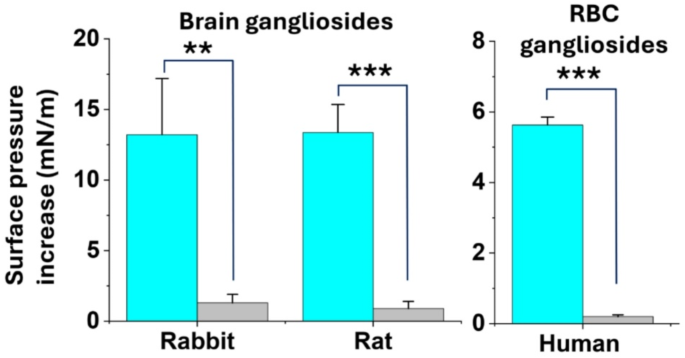

Brain ganglioside composition changes between mammal species. To perform reliable drug toxicity test, we needed to choose animal species whose brain ganglioside composition is similar to humans. Careful analysis of the literature suggested that rodents and rabbits are the most reliable species for our study30. We thus analyzed the binding of AmyP53 to rat and rabbit brain gangliosides. After extraction and purification from brain tissues, gangliosides were spread as monolayers at the air-water interface and incubated with AmyP53 added in the aqueous subphase. As shown in Fig. 9, AmyP53 efficiently interacted with brain gangliosides purified from rats or rabbits. For comparison, we performed a similar analysis with gangliosides extracted from human red blood cells which, like the human brain, expresses GM153 and GM354. These gangliosides are also recognized by amyloid proteins, including Aβ and α-synuclein40. Thus, as expected from the beneficial effects of AmyP53 in cellular human models, the peptide recognized these gangliosides of human origin (Fig. 9). Overall, the capacity of AmyP53 to recognize human, rat and rabbit gangliosides validated the choice of these two animal species for further toxicology studies.

Interaction of AmyP53 with gangliosides extracted from the brain of rats and rabbits and from human red blood cells (RBC). Gangliosides were spread as stable monolayers at the air-water surface. AmyP53 (10 µM) was injected underneath these monolayers and the interaction was followed by measurements of the surface pressure increase (blue histograms). The grey histograms represent a control experiment without AmyP53. In all cases the data are expressed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments (plateau values reached after 60 min of incubation). The statistical significance of the data was assessed using Student’s t-test (**, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001).

A summary of toxicology data is presented in Table 2. Repeated intranasal administration of AmyP53 to male and female rats for 28 days and 14 days of recovery after cessation of the treatment, at dose levels of 0.1, 1.0 and 5.0 mg/kg body weight/day was well tolerated and did not cause any symptoms indicative of local and/or systemic toxicity. Histological analysis did not reveal any abnormality. Cardiorespiratory analysis after intranasal administration of AmyP53 at the highest dose (5 mg/kg BW) also revealed no abnormality.

AmyP53 was also repeatedly administered intranasally to male and female rabbits during 14 days at dose levels of 0.1, 1.0 and 5.0 mg/kg body weight/day. The results showed no systemic or local toxicity during the in vivo phase of the study or at post-mortem. The dose level of 5.0 mg/kg/day was considered the No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL) for the intranasal route in both rats and rabbits (Table 2). Finally, the bacterial reverse mutation assay (Ames test, modified for histidine-containing peptides), which detects potential genotoxicity55, was negative (Table 2).

Physicochemical characteristics and metabolic stability of AmyP53 in vitro

To assess the suitability of AmyP53 for further drug development, we tested its metabolic stability in plasma and its binding to plasma proteins. First, 1 µM AmyP53 was incubated at 37 °C for various times (0–4 h) with plasma from rat, rabbit, mini-pig and dog. The stability of AmyP53 was determined by measuring the amount of intact compound by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). The data indicated a very good metabolic stability with half-life times of 83 min (dog), 364 min (mini-pig), 601 min (rabbit) and 787 min (rat) (Table 3). For comparison the half-life times of propantheline, an antimuscarinic agent used for the treatment of enuresis56, used here as a control, were 104 min (dog), 179 min (mini-pig), 17 min (rabbit) and 227 min (rat) (Table 3). These data are consistent with the design of AmyP53 which lacks consensus proteolytic sites for human plasma proteases (https://web.expasy.org/peptide_cutter/ as accessed on October 1st 2024).

Second, we analyzed the binding of AmyP53 to plasma proteins of the same four animal species (rat, rabbit, dog, mini-pig) by rapid equilibration dialysis (RED), compared with propranolol. After 2 h of incubation at 37 °C, the bound fraction of AmyP53 ranged from 81.7 ± 0.8% (rabbit) to 93.4 ± 0.6% (rat) (Table 3). These data showed that a large proportion of AmyP53 binds to plasma proteins, which may contribute to increase its stability in vivo and improve its biodistribution as already shown for therapeutic drugs including peptides57,58,59. These stability studies are consistent with the pharmacokinetics parameters of AmyP53 administered intranasally in rats (Table 4). Under these conditions, AmyP53 is detected for several hours in the brain with a Tmax of 5 min and a t1/2 of 61 min47.

Discussion

There is currently no effective treatment for PD. We propose here an innovative strategy based on a paradigm change. On one hand, in contrast with symptomatic approaches, we tackle the earliest step in the neurotoxicity cascade induced by α-synuclein oligomers that are now considered as a marker and responsible for PD development60,61. This is thus a disease-modifying strategy. On the other hand, in contrast with immunotherapies directed against the different forms of α-synuclein (monomeric, oligomeric, fibrils) we do not develop an α-synuclein centric approach because α-synuclein fulfills important physiological functions62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71 that need to be preserved upon treatment. We thus must be very cautious with therapeutic strategies targeting α-synuclein. In particular, non-pathological α-synuclein controls a number of critical regulatory functions associated with neural plasticity72, synaptic vesicle recycling, dopamine release, exocytosis and endocytosis, vesicular trafficking, interaction with SNARE proteins, and roles in lipid/fatty acid metabolism and transport73,74,75,76. Apart from these functions, non-pathological α-synuclein is reported to interact with a wide range of intracellular membranes, which is suggested to be relevant for its normal physiological roles77. Thus, it is reasonable to think that an abnormal membrane interaction could lead to neuronal dysfunction and cell death.

The poor specificity of anti-α-synuclein antibodies works against their use in clinics. Indeed, Kumar et al.78 studied a panel of 16 anti-α-synuclein antibodies using distinct experimental approaches, including single molecule assays, surface plasmon resonance, and immunoblotting. This study clearly showed that all the antibodies claimed to be ‘oligomer/conformation-specific’ cannot distinguish between oligomeric, fibrillar and monomeric α-synuclein. The reason for this lack of specificity emanates from the disordered nature of α-synuclein which belongs to the class of IDPs. The conformations adopted by α-synuclein in the oligomeric, prefibrillar and/or fibrillar forms can probably preexist in the myriads of conformations of the monomeric protein. If one of these conformers is recognized by an antibody, then this antibody will bind to all multimeric forms in which this conformer is present. Thus, this explains why it is potentially impossible to obtain antibodies that bind specifically to a given form of α-synuclein and totally ignore the other forms.

We propose to give up α-synuclein centric approaches and instead tackle the problem from a different angle. We focused on PD-related plasma membrane targets that are critical players in the formation of neurotoxic annular oligomers: the gangliosides18. Thus, modulating the membrane binding of α-synuclein is clearly a solution to design disease-modifying therapeutic drugs for PD treatment79,80. In this respect, the development of drugs targeting membrane gangliosides has tremendous potential and interest81. This is the route we are opening with the adaptive peptide AmyP53.

AmyP53 is an excellent example of an adaptive peptide82. Its amino acid sequence is derived from a disordered motif present in two IDPs which adopts a functional loop structure during interaction with raft gangliosides. Hence, the key feature of AmyP53 is that it does not have any particular 3D structure in solution, but it folds into a turn structure upon binding to raft gangliosides, as demonstrated by circular dichroism studies (Fig. 4) and molecular dynamics simulations (Figs. 3 and 5). When incubated in competition with wild-type or PD-associated mutated forms of α-synuclein, AmyP53 always wins the race to lipid raft gangliosides, due to its condensed electropositive surface potential. This unique property is at the basis of the potent inhibitory effect of AmyP53 on the formation of pore-like annular oligomers in the plasma membrane of brain cells (Fig. 6). It is essential to acknowledge that AmyP53 is efficient not only on wild-type but also on several mutant forms of α-synuclein (A30P, E46K, A53T) (Figs. 1 and 6) that are associated with genetically inherited PD83. Under our experimental conditions, we determined that all mutant forms of α-synuclein have a higher affinity for GT1b ganglioside monolayers, including A30P (Table 1). This result may be interpreted as surprising, given that the A30P mutant of α-synuclein is generally considered to have a lower affinity for lipid membranes compared to wild-type and other mutant forms84,85. However, there are some inconstancies in the literature between the membrane interaction of A30P and other α-synuclein proteins86. For instance, isothermal calorimetry studies showed that A30P shared a similar binding affinity to wild-type α-synuclein in a gel phase whereas binding was weaker in the liquid crystalline phase87. Since gangliosides also form a liquid ordered (Lo) phase88, our binding data are consistent with these previous studies. Moreover, it has also been demonstrated that α-synuclein binds to model membranes containing anionic phospholipids in a manner that is not sensitive to the A30P mutation89. This may also be the case for GT1b monolayers which bear a high density of electronegative charges, suggesting that electrostatic attraction might be the main mechanism controlling the interaction of α-synuclein proteins with lipid rafts. Indeed, the A30P mutation does not affect the electrostatic surface potential of the protein. Finally, in agreement with our binding data, Ca2+ imaging experiments (Fig. 6) revealed that the A30P mutant is also the most potent α-synuclein protein for amyloid pore formation. In this respect, the potent inhibitory effect of AmyP53 on the A30P mutant is particularly interesting. Overall, these quantitative data confirm and extend previous preliminary findings published by our group83.

AmyP53 is also efficient in an animal model of PD based on the loss of dopaminergic neurons induced by α-synuclein protofibrils injected into mice brains (Fig. 8). In this study, AmyP53 was co-injected with α-synuclein to ensure that the peptide was present in the brain when α-synuclein protofibrils are injected, to optimize its effects. Then AmyP53 was administered once a day intranasally for 7 days (pre-assessment study) or 35 days (whole study). This protocol was chosen to limit the number of animals used in these experiments for ethical reasons. However, considering the relatively short half-life of AmyP53 in the brain (about 1 h)47, it is highly likely that the initial injection of the peptide into the SNpc is not a determining parameter for the therapeutic effect. Daily administration of AmyP53 by the nose-to-brain route is definitely the protocol that we will implement for clinical trials in humans, excluding any invasive intervention. From a mechanistic point of view, the protective effect of AmyP53 in the animal model of PD was attributed to the binding of AmyP53 to brain gangliosides as demonstrated with gangliosides extracted and purified from the brain of rodents and rabbits. Indeed, AmyP53 had no effect by itself on baseline intracellular levels of Ca2+ (Fig. 6C). Moreover, the peptide did not induce any neurologic effects related to neurobehavioral functions associated with excitation, sedation, stereotypy, motor-coordination, autonomic and pain (Irwin test, Table 2).

AmyP53 is a membrane lipid targeted therapy that for the first time considers globally the lipid raft entity as a pharmacophore. Due to its ability to adopt several conformations during its journey on a lipid raft, AmyP53 spreads on several areas of the raft almost simultaneously, as suggested by molecular dynamics studies36. Indeed, after an initial binding step in the central zone of the raft, where the electronegative field is the strongest, AmyP53 reaches peripheral zones where it can form stabilized complexes with gangliosides displaying higher flexibility. This is a critical point because the natural target of amyloid proteins such as α-synuclein are those gangliosides located at the periphery of lipid rafts where they have sufficient conformational plasticity to accommodate the disordered amyloid proteins36.

Lipid raft gangliosides are upstream molecules involved at the very first step in the pathophysiology of PD and AD90. AmyP53 targets this earliest step and blocks the neurotoxic Ca2+ cascade that is responsible for the neuronal dysfunction and eventual loss in neurodegenerative diseases91. Most importantly, we demonstrate that AmyP53 efficiently binds to ganglioside GT1b which has a higher affinity for Aβ than GM142 and represents a key target for AD and potentially for other neurodegenerative therapies including PD90. In line with this notion, the protective effects of AmyP53 have been demonstrated on an ex vivo model of AD (hippocampal slices)83 and now in an animal model of PD (Fig. 8). Thus, AmyP53 is the first therapeutic candidate with a dual inhibition function against Aβ and α-synuclein toxicity. AmyP53 marks a significant milestone for developing disease-modifying therapeutics for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Its unique design opens the route for a series of adaptive peptides against other diseases associated with amyloid proteins and/or IDPs targeting lipid rafts.

To further investigate the therapeutic potential of this peptide in humans, we performed a series of preclinical toxicology and pharmacokinetics studies in rats and rabbits (Table 2), whose raft gangliosides are recognized by AmyP53 (Fig. 9). The design of this peptide excluded any potential toxic domain, in particular the cholesterol binding domain of amyloid proteins that can form annular oligomers by itself as shown for Aβ22−3592. The safety of AmyP53 treatment was previously demonstrated in several cell culture models47 and by initial studies in rats which demonstrated that the maximal tolerated dose of AmyP53 was > 5 mg/kg body weight after a one-week intranasal administration and > 80 mg/kg after a one-week intravenous administration48. These data were fully confirmed and extended in new toxicology studies performed in rats (28 days) and rabbits (14 days) (Table 2). The NOAEL for intranasal administration of AmyP53 was > 5 mg/kg in both species, which is several orders of magnitude above the therapeutic doses used in the present study. Indeed, the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of AmyP53 on the formation of Ca2+-permeable oligomeric pores was previously determined to be 30 nM in competition experiments with 220 nM of Aβ1−4248. These data are consistent with the observation that AmyP53 is able to saturate the lipid raft surface at concentrations significantly lower than α-synuclein (Fig. 1). In this respect, it is important to note that AmyP53 does not target the amyloid protein, but the lipid raft. If AmyP53 can saturate the lipid raft surface at a given concentration, this concentration is expected to be inhibitory for any amyloid protein since none of them displays an affinity for the raft superior to that of AmyP53. In other words, the concentrations of AmyP53 that prevent the formation of Aβ1−42 oligomeric pores should work for all other amyloid proteins, including α-synuclein.

Finally, AmyP53 did not induce any impairment of cardiorespiratory and cognitive functions, and it is not mutagenic as demonstrated by the Ames test. Moreover, AmyP53 efficiently reaches the brain after intranasal administration, with a half-life of 61 min in rats47. These pharmacokinetics data (Table 4) are in line with the high stability of this peptide in plasma, which is probably due to its binding to plasma proteins (Table 3).

Based on the cumulative findings from these preclinical studies, we conclude that AmyP53 is a robust alternative to any other potential treatment for PD and related synucleopathies. Moreover, since the AmyP53 formula is based on an amino acid combination of the ganglioside binding domain from α-synuclein and Aβ40, it can be considered as an α-synuclein/Aβ combination therapy in a single molecule. This property is not anecdotical because it is now becoming obvious that pure neurodegenerative diseases are rather rare. Instead, mixed pathologies (also referred to as overlapping conditions of co-pathologies) seem to be the rule93,94,95,96. Thus, both α-synuclein and Aβ oligomers are probably involved in the pathogenesis of AD and PD, leading the scientific community to consider that these diseases would need therapies targeting simultaneously each of these proteins97. In this respect, AmyP53 fulfills these criteria through its dual target mechanism98.

Materials and methods

Materials

The batches of AmyP53 (amino acid sequence KEGVLYVGHHTK, purity > 98%), used in this study were synthesized by Provepharm (Marseille, France) and Proteogenix (Schiltigheim, France). Stock solutions (up to 200 mg/mL) were prepared in HPLC-grade water and stored at − 20 °C before use. Ganglioside GT1b was purchased from Matreya (State College, PA, USA). Recombinant α-synuclein proteins were purchased from rPeptide (Watkinsville, GA, USA).

Calcium assay

Aged cultured of SH-SY5Y cells (> 10 consecutive passages) were loaded with 5 µM Fluo-4AM for 30 min in the dark, washed three times with Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) and incubated 30 min at 37 °C. Calcium fluxes were estimated by measuring the variation in cell fluorescence intensity after wild-type or mutant α-synuclein injection (220 nM) into the recording chamber directly above an upright microscope objective (BX51W Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with an illuminator system MT20 module83. Fluorescence emission at 525 nm was imaged by a digital camera CDD (Hamanatsu ORCA-ER, Hamamatsu, Japan) after fluorescence excitation at 490 nm. Time-lapse images (1 frame/10 s) were collected using the CellR Software (Olympus). Fluorescence intensity was measured from region of interest (ROI) centered on individual cells. Signals were expressed as fluorescence after treatment (Ft) divided by the fluorescence before treatment (Ft0) and multiplied by 100. All experiments were performed at 30 °C during 75 min. At the end of the calcium assay, fluorescent images were taken. In each condition, the morphology of cells was traced, the area and the fluorescent intensity were determined using the ImageJ software. Then, the ratio area/fluorescence was determined for each cell and averaged for each condition. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Plasma stability of AmyP53 in rat, rabbit, mini-pig, and dog plasma

400 µL of dipotassium ethylene diamine tetraacetic Acid (K2-EDTA) plasma from male animals of the indicated species were incubated with AmyP53 (1µM) or Propantheline bromide (1 µM) used as control. The times varied between 0 and 4 h. At the end of each incubation, 2-fold volume of cold acetonitrile with internal standard (100 ng/mL phenacetin) was added to the samples which were immediately analyzed by LC-MS/MS on a Waters Acquity UPLC + Waters TQXS Triple Quadrupole MS using a Waters Acquity HSS T3 (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm) column with pre-column guard filter.

Plasma protein binding of AmyP53 in rat, rabbit, mini-pig and dog by rapid equilibration dialysis (RED)

400 µL of K2-EDTA plasma from male animals of the indicated species were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with AmyP53 (5 µM) or Propanolol (1 µM) used as control. Samples were analyzed on LC-MS/MS as described above. The unbound fraction was calculated from the response (ratio of analyte peak area to internal standard peak area) obtained for each matrix:

(:{A}_{receiver}) is the analyte response in the sample collected from the receiver side and (:{A}_{donor}:)is the analyte response in the sample collected from the donor side.

Recovery of the experiment was calculated as follows:

Vdonor and Vreceiver are the volumes of the donor side matrix (200 µl) and the receiver side matrix (350 µl) in the RED experiment, respectively. Arecovery is the analyte response in the recovery sample. The recovery sample was prepared by pooling the remaining amounts of spiked donor side matrixes (replicates) together and preparing these for analysis in the same manner as donor side samples. The sample was prepared for analysis immediately after starting the RED experiment99.

Animal model of PD

Animals

All experiments were performed by Neuro-Sys (Gardanne, France) under the reference ARE22.01 W in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and followed current European Union regulations (Directive 2010/63/EU). Agreement number : A1301337. C57BL/6 mice were being provided by Janvier Labs (Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France).

α-synuclein protofibril Preparation

Human α-synuclein (stock at 69 µM in water) was reconstituted at 50µM in NaCl, 0.9% (final concentration) and incubated at + 37 °C for 3 days. A typical preparation includes monomeric form (20%), small oligomers (from 25 to 100 kDa; 50%) and large oligomers/fibrils (higher than 100 kDa; 30%)51.

Stereotaxic injections of α-synuclein protofibrils and AmyP53 treatment

Human α-synuclein protein (stock at 69 µM in water at -20 °C) was reconstituted at 50 µM in NaCl, 0.9% (final concentration). A specific preparation was made for the group treated with AmyP53: human α-synuclein was reconstituted at 50µM in NaCl, 0.9%, containing AmyP53 (100 µM final concentration). Mice were subjected to surgery and received 2.5 µL of α-synuclein solution. Mice were anesthetized by isoflurane (4%, for induction), in an induction chamber coupled with a vaporizer and to an oxygen concentrator. Mice were placed on the stereotaxic frame. Anesthesia was maintained by isoflurane (2%) with a face mask coupled to the isoflurane vaporizer and oxygen concentrator machine. Skull was exposed, and holes were drilled. Mice from group 3 were injected with a preparation containing α-synuclein (50 µM) and AmyP53 (100 µM). In this group, the intracerebral administration of AmyP53 was followed by daily treatment of the mice by the intranasal route. The α-synuclein preparations were bilaterally injected into the SNpc, at the following coordinates: A-P, − 0.3 cm; M-L, ± 0.12 cm; D-V, − 0.45 cm51. Depth of anesthesia and rectal temperature were verified every 5 min. After surgery, mice were allowed to recover before being placed back in the cage. The animals in vehicle-treated groups were injected with saline. The safety of AmyP53 was assessed, in a preliminary step, in 5 young mice (4-month-old).

Tissue collection for immunostaining

At the end of the experiment (on day 35 post-surgery), mice were deeply anesthetized and perfused with cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (3 min), and cold paraformaldehyde (PFA) 4% in PBS (3 min). Immunostaining was performed with n = 5/group. Brains were dissected and further fixed in PFA 4%, overnight at 4 °C, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in Tris-phosphate saline (TBS) solution at 4 °C. Coronal sections, including the SNpc, of 40 μm thickness were cut using a cryostat (4 sections per mouse, each 100 mm apart). For immunostaining, free-floating sections were incubated in TBS with 0.25% bovine serum albumin, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1% goat serum, for 1 h at room temperature. 4 brain sections per animal were processed and incubated for 2 h at room temperature with chicken polyclonal anti-tyrosine hydroxylase antibodies (1/1000). These antibodies were revealed with Alexa Fluor 568 anti-chicken IgG, at the dilution 1/500, in TBS with 0.25% donkey serum albumin, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 1% goat serum. Images for quantification (Fig. 8E) were acquired with a confocal microscope LSM 900 with ZEN software at 20x magnification (Zeiss) using the same acquisition parameters (automatic acquisition). The following read-outs were measured: (i) number of TH positive cells in the SNpc, (ii) intensity of TH staining. Images of larger brain slices (Fig. 8A–C) were scanned on a Zeiss LSM 980 confocal microscope using the ZEN 3.5 software. The images were acquired using a Plan-Apochromat 20x/0.8 M27 objective (stacks of 17–18 images were captured with an interval of 1.5 μm, and an optical zoom of 1). Full pictures were assembled using the orthogonal projection of the ZEN software. Then the different tiles were fused using the “fuse tile” option with a minimal overlap of 10 and a maximal shift of 20.

Molecular modeling simulations

AmyP53 was modelized de novo using the software HyperChem40. The Charmm topology and parameters of Amyp53 were generated using the tool “Automatic PSF Builder” on VMD software100. The coordinates and the topology of cholesterol (CLR) and GT1b constituting the cluster GT1b/CLR. The lipid bilayer composed by 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and CLR in ratio 1:1 was built using the tool “Bilayer Builder” available on CHARMM-GUI101,102. Each element was merged to create our system which consists of Amyp53 and the α-synuclein placed at 12 Å above the surface of the lipid raft inserted in a POPC bilayer. Finally, the system was solubilized with TIP3P water model and neutralized with the addition of Na+ and Cl– ions at a final concentration of 0.15 mol/L using the tools “Add solvation box” and “Add ions” supported by the software VMD. The system was simulated using the software NAMD 2.14 for Windows 10 coupled with the force field CHARMM36m103,104. The system was minimized for 10,000 steps to remove all bad contact between atoms and equilibrated at constant temperature (310 K) and constant pressure (1 atm) for 5 ns with constraint on the peptide followed by 5 ns with constraint on the peptide backbone, then, productions runs were performed.

Monolayers studies

AmyP53-ganglioside and α-synuclein-ganglioside interactions were studied with the Langmuir film balance technique with a fully automated microtensiometer (µTROUGH SX, Kibron Inc. Helsinki, Finland). The interaction of a peptide (or a protein) with a ganglioside monolayer is an interfacial phenomenon which can be studied by surface pressure (π) measurements105. The interaction of a protein with a ganglioside monolayer can be detected, at constant area, by an increase in the surface pressure (Δπ). This increase is caused by the insertion of the protein between the polar heads of vicinal gangliosides, which is not counterbalanced by an increase of the area of the monolayer. This effect can be followed kinetically by real-time surface pressure measurements after injecting the protein into the aqueous subphase underneath the ganglioside monolayer (or gangliosides extracted from animal brains) as described previously106. The initial velocity of the insertion process is expressed as mN.m−1.min−1. A logistic curve fitting [f(x) = 1/1 + e−x] has been done with the OriginPro software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA).

Ganglioside extraction and quantitation

Gangliosides extracted from rat and rabbit brains and human red blood cells were recovered from the upper phase of a Folch partition as previously described83.

Toxicology studies in rats and rabbits

The regulatory toxicology studies of AmyP53 in rats and rabbits were performed by independent CROs (Etap-Lab, Vandoeuvre-lès-Nancy, France; Area Produttiva-Roma, Italia; Vivotecnia, Madrid, Spain) under good laboratory practice (GLP) conditions with the authorization of French, Spanish and Italian health agencies. Methods, route of administration and doses are summarized in Table 1. Rats that completed the scheduled test period were euthanized by carbon dioxide. Rabbits that completed the scheduled test period were sedated (Dorbene Vet®) and killed by intravenous injection of a suitable agent (Tanax®). The intranasal and intravenous administration of AmyP53 for the pharmacokinetics studies were performed by Syncrosome (Marseille, France)47. Cardiorespiratory studies in rats were performed by ERBC (Baugy, France).

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance was tested using Student’s t-test or One-Way ANOVA with post-hoc T-tests.

Ethical statements

This study is reported in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines (https://arriveguidelines.org). The experimental protocols for toxicology studies in rats were approved by the Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation of Vivotecnia that promotes the use of alternative methods, the reduction in the number of animals used and the refinement in the experimental protocols applied. The experimental protocols for toxicology studies in rabbits were approved by the Ethics Committee of ERBC according to European regulations on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes and fully accredited by AAALAC (Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care). Animal welfare Procedures and facilities were compliant with the requirements of the Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. The national transposition of the Directive is defined in Decreto Legislativo 26/2014. ERBC test facility is fully accredited by AAALAC. Aspects of the protocol concerning animal welfare have been approved by ERBC animal-welfare body. For the in vivo mouse model of PD (Neuro-Sys), experiments were carried out in accordance with the National Research Council (US) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and followed current European Union regulations (Directive 2010/63/EU). The agreement number for the use of laboratory animals is A1301337 (in vivo mouse model of Parkinson’s disease).

Responses