Preclinical use of a clinically-relevant scAAV9/SUMF1 vector for the treatment of multiple sulfatase deficiency

Introduction

Multiple sulfatase deficiency (MSD, OMIM # 272200) is an autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder caused by homozygous or compound heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in the SUMF1 gene1,2. SUMF1 encodes formylglycine generating enzyme (FGE), a rate-limiting enzyme that catalyzes the post-translational modification of all known 17 sulfatases. Most disease-causing variants are missense alleles that decrease enzyme activity or shorten the half-life of the FGE protein. Without FGE modification of the common active site cystine residue of sulfatases into C-alpha-formylglycine3, newly synthesized sulfatases are not activated in the endoplasmic reticulum. In eukaryotic cells, sulfatases catalyze the hydrolysis of sulfate esters such as glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) and sulfatides. In the absence of sulfatase activity, GAGs and sulfatides accumulate and cause cellular dysfunction, leading to severe diseases.

MSD is a devastating, progressive, multisystemic pediatric disorder with a median age of death of 13 years. Clinical symptoms arise from the additive effects of each individual deficient sulfatase, which includes the enzymes responsible for known inherited single sulfatase disorders that are known as lysosomal storage diseases (i.e., metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD) and six mucopolysaccharidoses (MPS) subtypes)4,5. All other sulfatases without known clinical correlation also contribute to the complex and variable phenotype found in individuals with MSD. Patients suffer from neurologic regression and somatic symptoms including respiratory complications, musculoskeletal abnormalities, cardiac dysfunction, loss of hearing, and issues with vision, including retinopathy and optic nerve abnormalities (for a full clinical review see ref. 6). There is an urgent unmet need for MSD treatments as there are no disease modifying therapies7. Gene replacement therapy is one treatment approach for MSD where FGE protein expression is restored to then activate the target sulfatases that are otherwise produced in patients. There are several ongoing AAV-based gene replacement clinical trials for multiple relevant monogenic sulfatase disorders, including MPSII (NCT04571970, NCT03566043), MPSIIIA (NCT02716246), MLD (NCT01801709), and MPSVI (NCT03173521) supporting this as a translationally relevant approach.

Here we report the development of a self-complementary AAV9 vector delivering optimized SUMF1 (scAAV9/SUMF1) to treat MSD, the design of which can be readily translated for clinical use. Using a severe Sumf1 knock-out (Sumf1−/−) mouse model of MSD8, we tested the benefits of treatment with our vector in mice shortly after birth and later in the disease course by administering virus into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) alone or in combination with an intravenous (IV) injection. We show that CSF administration of scAAV9/SUMF1 is sufficient to rescue early lethality, normalize behavior, and improve visual and cardiac dysfunctions in Sumf1(−/−) mice, even when given at an advanced disease stage. We demonstrate dose-dependent and long-term restoration of sulfatase activity in tissues, which is accompanied by decreased accumulation of GAGs, lysosomal defects, and neuroinflammation in the brain. Even at the highest dose tested, scAAV9/SUMF1 is well-tolerated, without any overt signs of toxicity from high viral loads or transgenic SUMF1 expression.

Methods

Mice

All animal experiments and procedures adhere to the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Jackson Laboratory. All mice were maintained in a specific pathogen free research colony at The Jackson Laboratory. B6;129P2-Sumf1Gt(RST760)Byg/ClearJ, (B6-Sumf1−/−) mice were donated to The Jackson Laboratory by Dr. Andrea Ballabio, TIGEM (Telethon Institute of Genetics and Medicine). A colony was established at the N4 backcross to C57BL/6J under the stock number 30711. A mixed genetic background stock was generated by outcross of B6-Sumf1(−/+) heterozygous mice with 129S1/SvImJ (stock number 2448), generating F1STOCK- Sumf1(−/+) mice which were later intercrossed to generate homozygous F2STOCK-Sumf1(−/−) mice for use in gene therapy test (here described as Sumf1−/−). Pups were sampled at P0 by toe clipping and genotyped by quantitative PCR using the following primers and fluorescent probe sets: Fwd common (5′-TGA GGA GGT AAT TAG GTC ACT GG-3′), Rv-Wild type (5′-TAC TGA GTG GGC CGT CTC TC-3′), Rv-Mutant (5′-CGG TAC CAG ACT CTC CCA TC-3′), Probe-Mutant-FAM (5′-CCT GAC TGC ACT GCA CTG AG-3′), Probe-Wild type-HEX (5′-CGG GAT TGA TGA CCT TAT AAG C-3′).

scAAV9/SUMF1 vector generation

An AAV9 vector was engineered to encode codon-optimized human SUMF1 (hSUMF1opt; ATUM). The vector plasmid contained the 1122 bp hSUMF1 coding sequence between a 796 bp chicken beta actin hybrid (CBh) promoter and a 143 bp simian virus 40 polyadenylation (SV40pA) signal. The transgene cassette was flanked by a WT and a mutant (deletion of D element) AAV2 ITR to enable self-complementary packaging. AAV vector was produced using methods developed by the University of North Carolina Vector Core facility, as described9. The purified AAV was dialyzed in PBS supplemented with 5% D-Sorbitol and an additional 212 mM NaCl (350 mM NaCl total). Vector was titered by qPCR10 and confirmed by PAGE and silver stain.

Gene therapy treatments

At either P1 or P7, homozygous Sumf1(−/−) and WT Sumf1(+/+) pups were randomized using GraphPad randomization tool, and enrolled in each treatment group. Mice of both sexes were used in studies. An N = 8-10 per sex and genotype were enrolled in each experimental arm. The experimental arms included the following groups Sumf1(−/−)—treated, Sumf1(−/−)—vehicle, Sumf1(+/+)—treated, Sumf1(+/+)—vehicle. Mice at P1 were cryo-anesthetized and injected in a single ventricle with 2 µl scAAV9/SUMF1 (2.8 1011 vg/mouse). For intrathecal delivery, mice at P7 were cryo-anesthetized and injected by lumbar puncture11 with 5 µl of scAAV9/SUMF1 at 7 × 1011 vg/mouse, 1.8 × 1011 vg/mouse, 4.4 × 1010 vg/mouse, or 1.1 × 1010 vg/mouse. For combined delivery intrathecal/intravenous, mice at P7 were anesthetized with isoflurane and injected with 5 µl IT and 5 µl IV scAAV9/SUMF1 (total dose 1.2 × 1012 vg/mouse). Number of animals and sex distribution is indicated in Table 1. All animal injections were performed by personnel blinded to genotype and experimental group. All animals were maintained in an SPF facility at The Jackson Laboratory, and housed in positively ventilated polysulfonate cages with HEPA filtered air at a density of 2–5 mice per cage. Filtered tap water, acidified to a pH of 2.5–3.0, and normal rodent chow was provided ad libitum. All mice were checked daily for survival and body weight until 2 months of age and later move to weekly monitoring. When animals presented a body weight loss of more than 15 % of maximum body weight and a low body conditioning score, they were considered at end point and humanely euthanized. For survival analysis, all animals found dead or euthanized by end point criteria were scored as 1, while animals euthanized due to poor body conditioning resulting from fighting wounds, or accidental non-disease relevant death, were scored as 0.

Behavioral assessments

The rotarod test was applied to assess motor-coordination deficits using an Ugo-Basile accelerating rotarod (model 47600). Mice were acclimated for 60 min prior to testing. Mice were placed on the rotating rod at 4 rpm which accelerated up to 40 rpm over the course of 300 s. Each mouse was subjected to 3 consecutive trials with a 45 s resting interval. The time for the mouse to fall from the rod was recorded in seconds. The average latency to fall of the three trials is represented at each time point.

The spontaneous alternation or Y-maze test was used to assess spatial working memory performance using a clear Plexiglas Y-shaped maze. The mice were acclimated for 60 min prior to testing. Mice were placed in the start arm, facing the center of the Y for an 8 min test period and the sequence of entries into each arm was recorded via a ceiling mounted camera integrated with behavioral tracking software (Noldus Ethovision). The percentage of spontaneous alternation was calculated as the number of triads (entries into each of the 3 different arms of the maze in a sequence of 3 without returning to a previously visited arm) relative to the number of alternation opportunities.

The open field test was applied to evaluate general activity with emphasis on locomotor activity and exploratory behavior phenotypes. The mice were acclimated for about 60 min in home cage. Subjects were placed individually in the center of the arena in an enclosed, vented and sound-attenuated environmental chamber. Two levels of infrared beams recorded horizontal and vertical activity. The tracking software (Fusion, from OmniTechElectronics™) converted beam breaks into variables including distance traveled (cm), vertical activity, time in different areas, etc.

Visual acuity

We used an opto-kinetic test to assess the ability of a mouse to discriminate visual stimuli. A 3D virtual system was used to determine opto-kinetic thresholds in untrained and unrestrained mice. Four adjacent LCD screens projected black and white lines that rotated around the perimeter of the mouse. A trained technician, blind to genotype, placed the animal in the optodrum (Striatech GmbH) and confirmed the mouse’s ability to track based on the movement of the mouse’s head with the direction of the contrast grating in real-time via closed circuit camera monitoring. Frequency thresholds (cycles/degree) were measured by systematically increasing the spatial frequency of the gratings at 100 % contrast until animals no longer track.

Electrocardiography

Unconscious electrocardiography was used to assess in vivo cardiac function in Sumf1−/−. Briefly, the mice were anesthetized using isoflurane and placed on the electrocardiography platform where anesthesia was maintained for the duration of the recordings. The electrocardiogram was recorded by means of electrodes placed sub-dermally into the limbs. The traces were recorded until 30–120 s after wave-form signals were obtained. Heart rate, R–R interval, and QRS interval were reported.

Sulfatase assays

Frozen tissues were homogenized in a 1:10 volume of ddH2O to tissue weight. Tissues were lysed using 5 mm steel beads in a Qiagen LT at 40 Hz for 3 min. Sulfatase enzymatic activity was measured as previously described1,12. For SGSH activity, 10 mM of 4MU-alpha-N-sulpho-D-glucosaminide (Biosynth-Carbosynth) was dissolved in a substrate buffer of 143 mM Na-acetate buffer (pH6.5) containing 8.5% NaCl and 0.1 M HCl. In a 96 well black plate, 10 μl of homogenates were incubated with 20 μl of substrate in substrate buffer at 37 °C for 17 h. Pi/Ci buffer (0.2 M Na2HPO4/0.1 M citric-acid, pH 6.7) was added, and tissues were incubated for an additional 24 h at 37 °C. Reactions were stopped with 200 μl of Stop Buffer (0.5 M NaHCO3/0.5 M Na2CO3 buffer, pH 10.7) and read at 460 nm. For GALNS assays, analyses were conducted as previously described13. In brief, homogenates were spun at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and then dialyzed overnight in cassettes at 4 °C in 10 mM Na-Acetate (pH 6) containing 100 mm NaCl. 20 μl of 1 mM 4-Methylumbelliferyl b-D-galactopyranoside-6-sulfate sodium salt (Biosynth-Carbosynth) in substrate buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 0.1 M Na-acetate, pH4.3) was added to 10 μl of dialyzed supernatant in a 96 well black plate and incubated for 17 h at 37 °C. Incubations were stopped with 200 μl Stop Buffer and read at 460 nm.

Glycosaminoglycans analysis

We used the Glycosaminoglycans Assay Kit (Cat#6022 Chondrex) following vendor protocols. The method is optimized for the detection of sulfated Glycosaminoglycans (sGAGs), using the binding properties of the cationic dye 1,9-dimethylmethylene blue. Chondroitin sulfate was used as standard for quantification. For normalization purposes, whole DNA was extracted from tissue lysates by precipitation with ice cold 100 % ethanol and concentration determined in a spectrophotometer measuring absorbance to 260 nm. The GAG content in tissues was normalized to DNA amount and expressed as µg sGAG/µDNA. The data was later represented as percentage of GAG content relative to the average sGAG in the Sumf1(−/−) vehicle group.

Biodistribution assessment

For vector biodistribution, total genomic DNA was purified from frozen tissue samples collected at end point (14 months for ICV treatment, or 18 months for IT and combined IT/IV) using a QIACube HT (Qiagen), following the 96 DNA QIACube HT Kit protocol. For vector expression, RNA was extracted in QIAzol lysis reagent and chloroform, purified using a QIAcube HT. Extracted RNA samples were treated with DNAse I (NEB), and cDNA synthesis performed using a Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). qPCR was performed by the UT Southwestern Vector Core Facility. The total amount of sample DNA (host genomes) was determined by SYBR green qPCR analysis with primers specific to mouse GAPDH (forward: CATCACTGCCACCCAGAAGACTG, reverse: ATGCCAGTGAGCTTCCCGTTCAG) and the copies of hSUMF1opt DNA withing each sample was determined by SYBR green qPCR analysis with primers specific for hSUMF1opt (forward: GAGTGGACGTCGGATTGGT, reverse: GCGGTAGCGGTAACAGTAGG). Quantification was performed as previously described14. Vector DNA is reported as the number of double-stranded vector copies per diploid mouse genome. Vector cDNA is reported as the number of double-stranded vector copies per copy of host genome DNA. Vector copies and genomic DNA were calculated as previously described14.

Histology analysis

Mice were euthanized at end point (14 months or 18 months) or when body condition met the criteria for human end point. Animals were perfused with PBS and tissues drop-fixed in 10% NBF. After 48 hs, fixative was removed, and specimens were processed for paraffin embedding using a Tissue-Tek TEC5 Embedding System (Sakura, Model 5100). FFPE samples were sectioned at 5 µm in a Leica Rm2255 microtome (Leica biosystems) and processed for H&E staining or immunohistochemistry staining.

Immunohistochemistry

Deparaffinized sections were processed on a Leica Bond RX (Leica biosystems) for automated immune staining using either anti-LAMP1 (Cat#14-1071-82, Invitrogen) at 1:1000 dilution, anti-GFAP (Cat# ab16997, Abcam) at 1:100 dilution, anti-Iba1 (Cat# ab178846, Abcam) at 1:2000 dilution. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin. All slides were scanned at 40x resolution in a full slide scanner Hamamatsu NanoZoomer S210 Digital slide scanner. Images were analyzed using CellProfiler (Cell image analysis software, The Broad Institute) and the percentage of stained area is reported.

Glycosaminoglycans staining

Tissues were fixed in methacarn buffer (methanol 60%, chloroform 30%, and acetic acid 10%) for 24 h and next day processed for paraffin embedding. Samples were sectioned at 5 µm with a Leica Rm2255 microtome (Leica biosystems). Deparaffinized sections were processed for Alcian blue staining8.

scAAV9/SUMF1 ISH

The analysis of scAAV9/huSUMF1op distribution was conducted by ISH using RNAScope probes (ACD, Biotechne) specific for huSUMF1opt (hSUMF1-codon-No-XMm-C1, Cat# 1077138-C1). FFPE specimens, collected at 18 months age, were sectioned at 5 µm. After deparaffinization, the sections were processed for automated ISH in a Leica Bond RX (Leica biosystems), following vendor standard protocols (ACD, Biotechne). Slides were scanned using Hamamatsu NanoZoomer S210 Digital slide scanner. Images were analyzed using CellProfiler (Cell image analysis software, The Broad Institute) and the frequency of scAAV9/huSUMF1op positive cells for each region of interest is reported.

GLP toxicology study in rats

A toxicology study was carried out by Charles River Laboratories (CRL) in 7–8 week-old Sprague-Dawley rats to test the safety of scAAV9/SUMF1 by either IT or ICM injection, with planned end points at day 29 or day 181 post-injection. Each dosing group had 5 males and 5 females per time point. The vector and vehicle injections were formulated in PBS containing 5% sorbitol and 0.001% pluronic F68. This study was reviewed and approved by CRL’s IACUC. ScAAV9/SUMF1 for this study was produced by Catalent, and the certificate of testing for this lot is provided in Supplementary Note 1.

Statistics and reproducibility

The n size for each experiment is indicated in the corresponding figure and Supplementary data 1. Each mouse is considered a biological replicate. All biochemical assays were performed on two to three technical replicates. All data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 9.2.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Groups were compared by two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s correction for multiple comparisons. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 for all comparisons. ROUT test was applied for outlier analysis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Development of self-complementary AAV9/SUMF1 vector

To treat MSD, we developed scAAV9/SUMF1, a recombinant serotype 9 AAV encoding a codon-optimized human SUMF1 transgene (hSUMF1opt) (Fig. 1a). The DNA sequence is modified such that the final amino acid sequence is unchanged, but the nucleotide sequence is altered for easier detection and potentially stronger expression. The transgene consists of the hSUMF1opt DNA coding sequence of 1122 bp between a 796 bp CBh promoter and a 143 bp simian virus 40 polyadenylation (SV40pA) signal. The CBh promoter and SV40 polyA drive strong expression but are small enough to allow for packaging into a self-complementary (sc) AAV vector15. The CBh promoter is identical to the construct previously characterized in rodents, pigs, and non-human primates16,17. As loss of SUMF1 affects a variety of cell-types, a ubiquitous promoter was selected. The upstream inverted terminal repeat (ITR; proximal to the promoter) is from AAV2, with the D element deleted to promote packaging of a sc genome. The downstream ITR (proximal to the polyA) is an intact wild-type (WT) AAV2 ITR. scAAV vectors are 10-100 times more efficient at transduction compared to traditional single-stranded AAV vectors18,19.

a Schematic of the self-complementary vector, scAAV9/SUMF1, carrying a full-length codon optimized human SUMF1 cDNA (hSUMF1opt) under the control of a CBh promoter and with a synthetic SV40 poly(A) tail. b Schematic of experimental design depicting AAV9 delivery and subsequent evaluation. scAAV9/hSUMF1 (2.8 × 1011 vg/mouse) was delivered at P1 via ICV injection. Sumf1(−/−) and Sumf1(+/+) pups were randomized across experimental groups, and N = 8–10 by sex enrolled into each study arm. Animals were monitored for survival and growth and tested for behavioral outcomes at 1.5, 6, 12 months. Study end point was 14 months. c Kaplan-Meier survival curves represent the survival of mice. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was applied for survival curve comparisons to Sumf1(−/−) untreated group. d Enzymatic activity for ARSA, ARSB, ARSC, ARSL, IDS, and SGSH in brain and liver tissues of mice at study end point. Values represent the enzymatic activity as a percentage of average Sumf1(+/+) sulfatase activity. e Behavior was assessed in Sumf1(−/−) -AAV9/SUMF1 and Sumf1(+/+)-untreated groups, starting at 1.5 month, and retested at 6 and 12 months. Rotarod data represents the average latency to fall in a three trials test. The average total distance traveled and vertical activity time in Open field, is reported at each time point. Spontaneous alternation is indicated as the average percentage of spontaneous alternations in a Y-maze. All data points represent individual mouse, bar graphs indicate mean ± SEM. Groups were compared by two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s correction for multiple comparisons. Exact p value is indicated in the figure and Supplementary Data 1. All schemes were created with BioRender.com.

ICV delivery of AAV9/SUMF1 rescued early lethality and extended life span of Sumf1(−/−) mice

To test the efficacy of our scAAV9/SUMF1 vector, we utilized Sumf1(−/−) mice8. Sumf1(−/−) mice were originally characterized as having a median survival of 30 days and at least 10 % of mice living longer than 180 days8. However, our initial breeding (JAX stock number 30711) resulted in a median survival of 1 day and a maximum life span of 13 days that was accompanied by a failure to thrive or gain body weight (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). This severe neonatal lethality was the consequence of at least 4 backcrosses of the original strain to C57BL/6J before being imported to The Jackson Laboratory. We performed a pilot study to test scAAV9/SUMF1 by treating at post-natal day 1 (P1) via intracerebroventricular (ICV) delivery in the B6-Sumf1(−/−) mice. Despite the extremely small window for therapeutic intervention, ICV delivery of scAAV9/SUMF1 increased the median age of survival of B6-Sumf1(−/−) mice from 1 day to 50 days and the maximum lifespan was extended from 13 days to the study endpoint of ~450 days (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Treated B6-Sumf1(−/−) mice gained body weight during development, however, they remained significantly smaller than WT littermates (B6-Sumf1(+/+)) (Supplementary Fig. 1d). The B6-Sumf1(+/+) mice treated with AAV9/SUMF1 had a normal life span and body weight gain without any changes to body condition or overall apparent health (Supplementary Fig. 1c, d), indicating that overexpression of SUMF1 is well-tolerated in mice.

While extending the lifespan of B6-Sumf1(−/−) mice with scAAV9/SUMF1 treatment was encouraging, the disease severity made it challenging to produce enough animals for testing and limited gene therapy intervention to neonates. Since the original B6-Sumf1(−/−) strain was developed on a mixed genetic background B6129S8, we introduced hybrid vigor by crossing heterozygous B6-Sumf1(−/+) mice with the inbred stock 129S1/J and the resulting F1 progeny were intercrossed to generate homozygous 129S1B6-Sumf1(−/−) null mice (hereafter indicated as Sumf1(−/−) mice). In the presence of a mixed genetic background, Sumf1(−/−) mice showed an increased median survival of 9–10 days with about 10 % of mice living more than 180 days, but they still showed reduced body weight and growth (Supplementary Fig. 1a, b). In the less severe Sumf1(−/−) model, we first tested for maximum efficacy by injecting mice at P1 via ICV delivery using the highest feasible dose of scAAV9/SUMF1 based on vector titer and injection volume, and mice were monitored for up to 14 months of age (Fig. 1b). ICV treatment of Sumf1(−/−) mice with scAAV9/SUMF1 showed a significant reduction of early postnatal lethality and extended the life span, with 50% of treated Sumf1(−/−) mice surviving more than 300 days (Fig. 1c). Despite the improvements in survival and general health, the treated Sumf1(−/−) mice still showed a reduced body weight compared to Sumf1(+/+) controls (Supplementary Fig. 1e, f).

ICV-delivered scAAV9/SUMF1 restored brain sulfatase activity and behavior of Sumf1(−/−) mice

Having found scAAV9/SUMF1 extended the lifespan of Sumf1(−/−) mice, we then determined if treatment restored SUMF1 activity by assessing the activation of sulfatases. At the endpoint of our treatment paradigm, brain and liver tissues were analyzed for the activity of various sulfatases including arylsulfatase A (ARSA), arylsulfatase B (ARSB), arylsulfatase C (ARSC), arylsulfatase L (ARSL), iduronate-2-sulfatase (IDS), n-sulphoglucosamine sulphohydrolase (SGSH) and N-acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfatase (GALNS). Consistent with previous studies using tissue from KO mice and patient derived fibroblasts8,20, Sumf1(−/−) mice showed a near-complete loss in sulfatase activity compared to WT mice (Fig. 1d). Importantly, ICV treatment with scAAV9/SUMF1 significantly increased the activity of the tested sulfatases in brain tissues, with levels restored back to 50-75% of that observed in WT mice (Fig. 1d). Consistent with the administration of scAAV9/SUMF1 into brain CSF, no to little improvement was found in sulfatase activity in the liver of ICV-treated Sumf1(−/−) mice (Fig. 1d).

In addition to biochemical defects, motor and cognition deficits are also described in Sumf1(−/−) mice12. To determine if restoration of sulfatase activity improved behavior, we assessed motor coordination by rotarod, general activity by open field, and cognition-memory through the spontaneous alternation test. Due to the early and drastic lethality observed in Sumf1(−/−) mice, we focused our behavior studies on Sumf1(+/+) control and scAAV9/SUMF1-treated Sumf1(−/−) mice. No significant defects in rotarod performance, open field activity, or spontaneous alternation were observed between Sumf1(+/+) and scAAV9/SUMF1-treated Sumf1(−/−) mice up to 12 months of age. Together, these results indicate that early ICV treatment significantly increased brain sulfatase activity, which was associated with improved survival and sustained normal behavior (Fig. 1e).

Delayed scAAV9/SUMF1 gene therapy extended life span of Sumf1(−/−) mice

While improved survival and restored sulfatase activity of neonate mice with our scAAV9/SUMF1 vector was encouraging, neurologically, treatment at P1 in rodents is equivalent to treating a human infant in utero21 and has limited translational relevance. To interrogate if SUMF1 gene therapy at a more advanced disease stage is beneficial, we treated mice at P7 using intrathecal (IT) CSF delivery (Fig. 2a) as it results in AAV9 transduction of brain, spinal cord and peripheral tissues16,22,23,24,25,26. As a prior study proposed that high systemic delivery is necessary to rescue Sumf1(−/−) mice due to non-nervous system phenotypes12, we also tested if combining a systemic, intravenous route of injection with IT delivery (IT/IV) could enhance therapeutic benefits (Fig. 2c). We found that high dose (HD) IT and combined IT/IV scAAV9/SUMF1 delivery were equally effective in rescuing early lethality in Sumf1(−/−) mice and expanding lifespan with ~60 % of mice living more than a year (Fig. 2d, Table 1). Similar to the ICV treatment (Supplementary Fig. 1e, f), neither IT nor IT/IV injection improved the defects in body weight and growth in Sumf1(−/−) mice (Supplementary Fig. 1g–j). Importantly, neither IT nor IT/IV treated-Sumf1(−/−) mice developed behavioral abnormalities as compared to control mice (Fig. 2e).

a Sumf1(−/−) mice were IT injected at P7 with scAAV9/SUMF1 at high dose (HD, 7 × 1011 vg/mouse), 1:4 dilution (1.8 × 1011 vg/mouse), 1:16 dilution (4.4 × 1010 vg/mouse), 1:64 dilution (1.1 × 1010 vg/mouse), vehicle, and untreated. Sumf1(+/+) mice were injected IT at P7 with either HD scAAV9/SUMF1 or vehicle. Balanced numbers of females and males by genotype were randomized across all the experimental groups. Animals were monitored daily until 3 weeks age, for survival and growth, and then weekly until end point at 18 months. HD groups were tested for behavior at 3 time points. Created in BioRender.com (b), Survival data for the dose-response groups is represented with Kaplan-Meier curves. c To test the efficacy of a combined gene therapy treatment (IT/IV), Sumf1(−/−) mice at P7, received dual IT and IV injections of scAAV9/SUMF1 (1.2 × 1012 vg/mouse). Survival and growth were monitored daily until 3 weeks of age, then weekly until end point at 18 months of age. Created in BioRender.com (d), Kaplan-Meier survival curves are reported. Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was applied to comparisons between survival of IT single dose vs combined IT/IV (p = 0.4155) and combined IT/IV vs Sumf1(−/−) -vehicle (p = 0.001). e Behavior testing of IT and IT/IV treated mice at 1.5, 6, and 12 months of age. Rotarod data is reported as the average latency to fall from a three-trial test. For open field test, average total distance traveled, and vertical activity time is reported. The spontaneous alternation test is indicated as the average percentage of spontaneous alternations in a Y-maze. Sulfatase activity was measured in f brains and g liver at the study end point. Data is represented as the percentage of sulfatase activity relative to the average levels in Sumf1(+/+) mice. All data points represent individual mouse, bar graphs indicates mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s correction for multiple comparisons. p values are indicated and can be accessed in Supplementary Data 1.

Treatment benefits from IT scAAV9/SUMF1 were dose-dependent

Having found IT and IT/IV HD were equally effective in improving survival and behavior, we tested the potency of scAAV9/SUMF1 by performing a dosing study using a single IT injection of serial four-fold dilutions of the HD. The HD and 1:4 diluted dose showed a similar rescue of early lethality and provided a significant increase in life span, while more diluted administrations were less effective in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2b, Table 1).

FGE activity was then assessed in all delayed-treatment animals at the study endpoint by analyzing sulfatase activity in brain and liver tissues. ARSA, ARSB, ARSL, IDS, and SGSH activities were restored in a clear dose-dependent manner with the HD IT/IV and IT being the most effective followed by IT at a 1:4 dilution (Fig. 2f, g). However, no significant difference in sulfatase activity was found between HD IT and IT/IV injection groups. Injection at P7 significantly improved enzymatic activity in brain tissues of Sumf1(−/−) and restored levels back to ~20–30% of that in WT mice (Fig. 2f), which was less than the restoration from ICV injection at P1 (Fig. 1d). In the liver, sulfatase activity improved by 5–20% of Sumf1(−/−) mice (Fig. 2g), which was greater than that achieved by P1 ICV treatment. Interestingly, analysis of brain and liver tissues of treated and untreated WT mice showed that treatment did not significantly increase sulfatase activity, suggesting that FGE protein activity is nearly maximal and may be rate-limited by sulfatase levels in WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b).

Cardiac and vision phenotypes were rescued by scAAV9/SUMF1 IT treatment

Sumf1(−/−) mice are reported to develop cardiac inflammation8. In agreement, by EKG analysis we detected a significant reduction in the heart rate of untreated Sumf1(−/−) mice compared to WT controls (Fig. 3a). After 12 months post-injection, both IT/IV and IT scAAV9/SUMF1 treatments were able to restore the heart rate to normal levels in Sumf1(−/−) mice (Fig. 3a). Similar to sulfatase activity, the level of cardiac phenotype restoration was dose-dependent, and no improvement was observed at the lowest tested 1:64 dose (Fig. 3a). Further quantification of GAG content in cardiac tissue showed a remarkable reduction of GAGs in Sumf1(−/−) mice treated with either IT/IV, HD IT, or 1:4 dilution IT (Supplementary Fig. 3).

a Heart function was assessed in vivo by electrocardiography of Sumf1(−/−) mice treated with gene therapy as single intrathecal (IT) high (7 × 1011 vg) and low dose (1.1 × 1010 vg) or combined IT/IV dose (1.2 × 1012 vg). Sumf1(+/+) control and Sumf1(−/−) -vehicle mice were included. Bar graphs represent the average heart rate, measured at 9 and 12 months of age. b Visual acuity was tested by opto-kinetics. The bar graphs represent the frequency thresholds (cycles/degree), measured at 9 and 12 months. All data points represent individual mouse, and bar graphs indicates mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s correction for multiple comparisons, Sumf1(+/+) -vehicle was used as reference for multiple comparison. P values are indicated and accessible in Supplementary Data 1.

Vision defects have also been reported in MSD-patients4,6 and other mouse models with deficiencies in Sumf127 and other sulfatases28,29,30. Thus, we performed a vision acuity test (optokinetic thresholds) on scAAV9/SUMF1-treated Sumf1(−/−) mice and controls. Interestingly, we observed a reduction of visual acuity at 9 and 12 months of age in vehicle-treated Sumf1(−/−) mice with an optokinetic threshold indicating that the mice were almost blind (Fig. 3b). Surprisingly, all Sumf1(−/−) mice treated with scAAV9/SUMF1 showed normal visual acuity at 9 months of age, even at the lowest dose of the vector (Fig. 3b). However, only the HD IT and IT/IV groups were able to maintain vision at 12 months of age (Fig. 3b), while Sumf1(−/−) mice treated with a low dose (1:64) of scAAV9/SUMF1 via IT injection still developed rapid vision degeneration between 9 and 12 months of age (Fig. 3b).

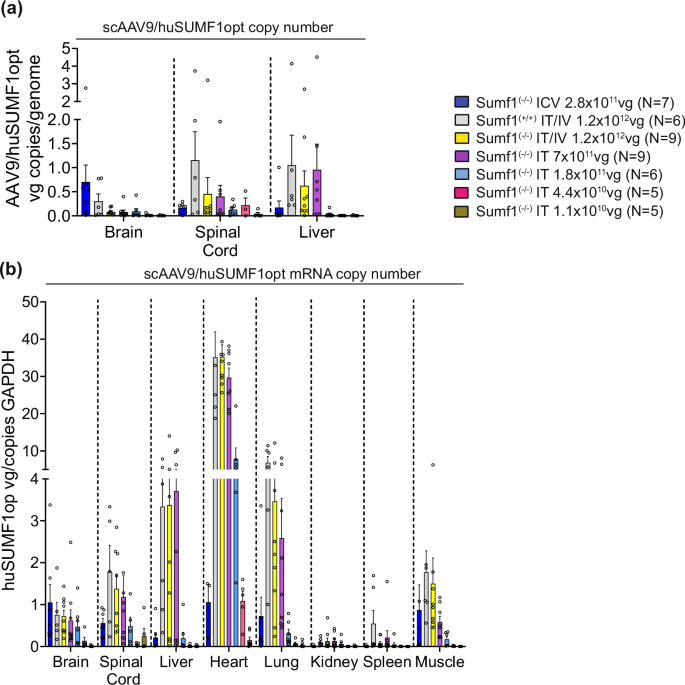

Biodistribution and expression of scAAV9/SUMF1

Vector distribution and expression were then assessed in treated mice. At 14 months post ICV-injection at P1 the highest levels of scAAV9/SUMF1 vector were detected in the brain while spinal cord and liver had relatively fewer viral copies (Fig. 4a). As expected23, in contrast, P7 treatment using IT or IT/IV dosing resulted in more vector copies in the spinal cord and liver and relatively fewer in the brain, with the IT/IV and IT HD resulting in similar vector copies (Fig. 4a). The abundance of vector copies from P7-IT injection was dose-dependent with scAAV9/SUMF1 vector at 1:4 dilution (1.8 × 1011 vg) still showing high transduction levels in spinal cord and brain (Fig. 4a). Further, gene expression data from P7 treatments, obtained as mRNA copies of hSUMF1opt, showed wide distribution across multiple peripheral tissues with heart, liver and lung being the highest and kidney and spleen being the lowest expressing tissues (Fig. 4b). In agreement with vector distribution, hSUMF1opt expression levels were dose-dependent, where HD IT alone provided similar expression levels as combined dosing via IT/IV. Additionally, the single IT 1:4 dilution achieved high expression levels in the brain, spinal cord tissues with more moderate efficiency in peripheral organs like heart, liver, and lungs. Of note, there were high expression levels in the heart, even at a 1:4 vector dilution (Fig. 4b).

a scAAV9/SUMF1 vector copy number was assessed in all the dosing groups by qPCR analysis of hSUMF1opt in genomic DNA from brain, spinal cord, and liver at study end point (14 months for ICV delivery, and 18 months for IT or IT/IV delivery). Data points represents individual mice, and bar graphs indicates mean ± SEM of vg copies/mouse diploid genome. b hSUMF1opt expression was determined at the mRNA level by RT-qPCR analysis of brain, spinal cord, liver, heart, lung, kidney, spleen, and muscle. Vector cDNA is reported as the number of vector copies per copy of host Gapdh. Data points represents individual mice, and bar graphs indicates the mean ± SEM, N = 5–9 per experimental group.

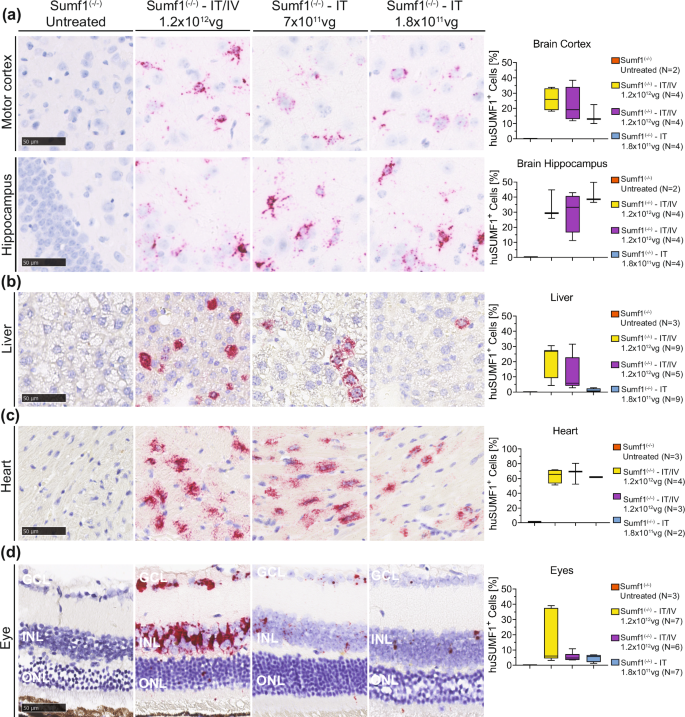

In situ hybridization (RNAscope™) analysis of scAAV9/SUMF1 expression further supported the qPCR biodistribution and gene expression results. Both IT/IV and IT HD treatment resulted in comparable frequencies of hSUMF1opt+ cells in cortex and hippocampus brain regions (Fig. 5a). The hippocampus (CA3) showed a remarkable high frequency of hSUMF1opt+ cells, even at the low dose 1:4 (Fig. 5a). The frequency of hSUMF1opt+ cells in liver was dose-dependent and the IT/IV treatment was the most efficient showing an average transduction frequency of 10% (Fig. 5B). Nevertheless, the single IT HD was sufficient to provide an average of 5% of hSUMF1opt+ cells (Fig. 5b). Both IT/IV and IT treatments (even at low 1:4 dose) resulted in a remarkable high frequency of hSUMFopt1+ cells in the heart showing an average of 60% of hSUMF1opt+ cells (Fig. 5c).

The transduction efficiency and tissue distribution of scAAV9/SUMF1 was assessed by RNA ISH (RNAscope™) at end point (18 months old) on tissues from mice injected with scAAV9/SUMF1 via single-IT high dose (IT-HD, 7 × 1011 vg), single diluted 1:4 dose (IT, 1.8 × 1011 vg), or combined high dose IT/IV (IT/IV, 1.2 × 1012 vg). Sumf1(−/−) untreated control samples, were collected at an average age of 248 days. hSUMF1opt-specific probes were utilized to detect the frequency for transduced cells. Representative images and quantification of hSUMF1opt in a brain (cortex and hippocampus), b liver, c heart, and d eyes (GCL ganglion cell layer, INL inner nuclear layer, ONL outer nuclear layer). Scale bar represents 50 µm. Image quantification, box plots represents median, min and max of the average number of AAV9/SUMF1 positive cells as a percentage of the total number of cells per section.

Additional RNAscope analysis showed that the treatments at P7 with scAAV9/SUMF1 resulted in a significant expression in eyes of Sumf1(−/−) treated mice (Fig. 5d). The resulting expression was clearly dose-dependent with IT/IV injection showing the highest frequency of hSUMF1opt+ cells compared to a single IT injection (Fig. 5d). Most of the transduced cells were present in the ganglion-cell layer (GCL) and the inner nuclear cell layer (INL). It is remarkable how the outer nuclear layer (ONL) is restored in mice treated with a HD via IT/IV or IT, while the mice receiving the lower 1:4 dose still shows signs of retina degeneration at the ONL (Fig. 5d, see cells located in ONL layer).

IT scAAV9/SUMF1 treatment rescued hepatic GAG accumulation and brain pathology

Sumf1 deficiency in mice causes impaired degradation and, thereby, cellular accumulation of GAG that ultimately leads to intra-lysosomal accumulation, lysosomal defects and neuroinflammation3. We found that delivery of scAAV9/SUMF1 via IT at HD and 1:4 dilution was effective in reducing hepatic GAG accumulation to levels comparable to those observed in Sumf1(+/+) mice (Fig. 6a, b). Furthermore, lysosomal defects and neuroinflammation measured via LAMP1 (lysosomal marker) and GFAP (astrocytes), respectively, were drastically reduced in the cortex and hippocampus of scAAV9/SUMF1-treated Sumf1(−/−) mice compared to untreated Sumf1(−/−) mice (Fig. 7a, b). Both high and low dose (1:4) gene therapy treatments were effective in reducing lysosomal accumulation (LAMP1) and neuroinflammation of astrocytes (GFAP) in the brain of Sumf1(−/−) mice (Fig. 7a, b). Interestingly, neuroinflammation in Sumf1(−/−) was not associated with a significant increase in microglia (Iba1) staining and was not significantly impacted by treatment besides morphological changes observed (Supplementary Fig. 4).

GAG tissue accumulation was detected by Alcian blue staining in liver sections of mice IT injected with scAAV9/SUMF1; high dose (HD, 7 × 1011 vg/mouse), 1:4 dilution (1.8 × 1011 vg/mouse), 1:16 dilution (4.4 × 1010 vg/mouse), and 1:64 dilution (1.1 × 1010 vg/mouse). Sumf1(−/−) and Sumf1(+/+) vehicle-injected were controls. a Representative images of liver sections. Scale bar represents 50 µm. b Alcian blue quantification represented as percentage of the stained area. Box plots represent the median, min, and max.

Brain sections from Sumf1(−/−) mice treated with scAAV9/SUMF1 as high dose IT (IT, 7 × 1011 vg), diluted 1:4 (IT, 1.8 × 1011 vg), combined high dose IT/IV (IT/IV, 1.2 × 1012 vg), vehicle, and Sumf1(+/+) vehicle-injected were immune-stained for a LAMP1 and b GFAP. Representative images of each stain are shown for the motor cortex and hippocampus. All images are presented at 40× magnification. Scale bar represents 50 µm. Image quantification represents the percentage of stained area for each marker. Data points represent individual mouse, and bar graphs indicates mean ± SEM, N = 2–9 per group. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Šídák’s correction for multiple comparisons relative to the Sumf1(+/+) vehicle group. The adjusted p value is indicated.

GLP rat toxicology study shows safety of scAAV9/SUMF1 CSF delivery

A Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) toxicology study was conducted in rats to evaluate the safety of scAAV9/SUMF1 CSF delivery. As indicated in Table 2, three dose levels were tested via intrathecal delivery and one single dose level by intra-cisterna magna (ICM) delivery. Administration of scAAV9/SUMF1 at all dose levels was not associated with any mortality, clinical observations (including neurological exam), body weight changes, food consumption changes, or changes in clinical pathology parameters that were considered adverse. There were no treatment-related effects on hematology, blood coagulation, or clinical chemistry at any time point. Histopathology analysis of rats injected IT at the target dose (2 × 1012 vg per rat, human equivalent dose of ~1 × 1015 vg per person), showed minimal severity inflammation/degeneration of lumbar and thoracic dorsal root ganglia (DRG) at day 28, with partial resolution by day 180; occasional spinal nerve root degeneration at day 28, with partial resolution by day 180; and low-grade white matter degeneration in the spinal cord at day 28, with resolution by day 180. At the highest dose (4.8 × 1012 vg per rat), similar findings were observed as the 2 × 1012 vg group, but trended slightly higher in terms of incidence/severity (occasional moderate severity findings). No AAV9/SUMF1-related neuropathies were noted for the sural sensory and radial sensory nerves, for which nerve conduction studies were conducted at baseline (predose), week 6, and day 180 post-injection. Minor maturation delays in peripheral sensory nerve conduction were observed in the highest dose only, but these were graded as negligible and not neuropathic. Overall, nerve conduction metrics remained within a normal functional range for all nerves at all timepoints. There were no apparent differences in findings between the IT and ICM routes of administration.

Discussion

MSD is a life-threatening neurodegenerative disease in children that affects the entire body and for which no treatment is available that halts or delays the disease progression. It is an inherited lysosomal storage disorder caused by genetic mutations in the SUMF1 gene that encodes the FGE protein that is necessary for the activation of sulfatases within all cells31,32. Since the disease is caused by insufficient amounts of functional FGE protein, gene therapy is a promising approach to increase functional FGE levels and is appealing due to the long-lasting effects of a single administration. Previous research demonstrated that a single-stranded AAV9/CMV-hSUMF1-FLAG vector in neonates can drastically alter disease progression and survival from 50% at 3 weeks to 60% at more than 12 weeks in a severe MSD mouse model (Sumf1−/−)12. While promising, this vector necessitated a combination CSF and IV administration to achieve benefit. Additionally, in this study only neonatal mice (P1 age) were treated, which neurologically is the equivalent of treating a pre-term infant21. As in utero gene delivery is currently not being conducted in humans as far as we are aware, and patients are rarely diagnosed prenatally, it is unclear if gene replacement therapy would benefit the more relevant population of MSD patients who would be treated later in brain development and in disease progression.

Considering these limitations, we developed a self-complementary AAV9/CBh-hSUMF1opt vector, the design of which could be readily translated for its application in humans. The scAAV genome has been shown to have higher transduction efficiency than single stranded AAV vectors18,19 The CBh promoter mediates robust and ubiquitous expression of the gene of interest and was selected for the purpose of multi-system expression to maximize levels of FGE protein15,16,17. We hypothesized that high levels of FGE protein would maximize activation of sulfatases, with secreted sulfatases providing potential cross-correction to neighboring cells. While high levels of certain proteins may cause toxicity, overexpression of FGE has been previously shown to be well tolerated in animals and humans12,33,34,35. In agreement with this, we did not observe any adverse effects, either overtly or by histopathological examination, in Sumf1−/− or littermate WT mice when treated with the vector. Compared to untreated or vehicle treated WT mice, scAAV9/SUMF1 treatment did not impact weight gain, survival, or body functions, including general activity, motor learning and coordination, cognition and memory, cardiac function, and vision. Analysis of brain and liver tissues of treated and untreated WT mice showed that treatment did not significantly increase sulfatase activity, suggesting that in WT mice baseline FGE protein activity is nearly maximal and may be rate-limited by sulfatase levels. Overall, we observed that scAAV9/SUMF1 treatment was well-tolerated even after a year post-dosing.

Furthermore, our results indicate a clear dose-dependent response of the treatment up to the maximum feasible IT dose based on volume and vector titer in P7 mice. Previous reports showed the need to target systemic organs with gene therapy via an IV injection following CNS targeting via an ICV injection to achieve a significant benefit in Sumf1(−/−) mice. In contrast, we found that CSF delivery of our clinically-relevant vector was sufficient for rescue and that combination IT/IV dosing did not significantly increase the treatment benefits compared to IT alone at P7. We speculate that this difference may originate, at least in part, from the use of the scAAV genome design, promoter selection, codon-optimization of the gene, and higher vector doses. Further, IT delivered AAV9 is known to leak from the CSF to the blood stream, resulting in peripheral transduction in addition to the CNS22,23,36. In agreement, the biodistribution and expression analysis showed that IT delivery at P7 of scAAV9/SUMF1 achieved significant transduction of the heart and brain, both of which are thought to be critical targets as cardiac insufficiency and neurological impairment likely contribute to early death in Sumf1(−/−) mice8.

With ICV-injection at P1 the highest levels of scAAV9/SUMF1 vector were detected in the CNS while the liver had relatively fewer viral copies, which corresponded with a relatively low increase in sulfatase activity in the liver. Comparatively, IT-delivery at P7 resulted in relatively greater liver transduction and activity, albeit it was to a lesser extent than expected based on prior work assessing CSF administration of AAV9 vectors in nonhuman primates and adult mice. The mechanism for this is unknown, however, we’ve observed similar results in mice IT injected at P14 or younger37. There could be differences in biodistribution to the liver when AAV9 is IT injected at P7 or could be caused by the rapid liver growth that occurs, which would result in vector genome dilution. It is important to note for the studies herein that the liver was assessed after 18 months post-injection.

Sumf1(−/−) mice present signs of cardiac inflammation8 and EKG analysis revealed a significant reduction in the heart rate of vehicle treated Sumf1(−/−) compared to WT mice. Both HD combined IT/IV and IT alone scAAV9/SUMF1 treatment at P7 restored the heart rate to normal levels in Sumf1(−/−) mice. The level of restoration was dose-dependent as Sumf1(−/−) mice treated with the lowest dose (1:64) still had lower heart rates and were comparable to those in vehicle treated Sumf1(−/−) mice.

Vision defects have also been reported in MSD-patients4,6 and other mouse models with sulfatase deficiencies27,28,29,30, and here we report, to the best of our knowledge, a newly described vision phenotype in Sumf1(−/−) mice. The vision acuity test (optokinetic thresholds) identified a severe deficit in vehicle-treated KO mice at 9 months of age. Surprisingly, all treated KO mice showed normal visual acuity at 9 months, even those treated at the lowest dose (1:64). However, only the KO mice treated with HD (IT or IT/IV) still had normal visual acuity levels at 12 months of age. This rescue coincided with the ONL restoration observed in mice treated with HD via combined IT/IV or single IT, while the mice that received a lower dose showed ONL degeneration. Since we detected good vector biodistribution into retina and brain cortical regions, we might expect that vision restoration occurs as consequence of pathology improvements in both brain and retina regions.

It should be noted that ARSA and IDS are secreted and may be measured in the plasma/serum38,39. ARSC is not secreted but localized to microsomes that can be detected in the tissue lysates along with ARSA and IDS. In agreement with this, we found that ARSC levels were restored to a greater extent, higher than ARSA and IDS in brain and liver tissues in treated Sumf1(−/−) mice. This difference may be due to the cell types that were transduced or could indicate that cells with active ARSA and IDS have a greater level of sulfatase secretion in an environment that is deficient in active sulfatases. Additional studies assessing sulfatase excretion and plasma levels of treated mice are needed to determine this.

In this study, we treated Sumf1(−/−) and WT littermates as neonates via ICV injections for proof-of-concept studies and pups at P7 via IT alone or combination of IT and IV injections for translationally relevant studies. Interestingly, all the tested treatment paradigms produced benefits as indicated by improved survival and behavior equivalent to that of WT littermates including gross motor function, motor coordination, cognition, and memory. In addition, we also observed restoration of sulfatase activity and a corresponding decrease in GAGs, neuroinflammation and lysosomal markers in brain and liver tissues of Sumf1(−/−) mice. Our measured outcomes, along with AAV9 biodistribution and SUMF1 expression levels, indicate effective targeting of critically affected cell populations via IT delivery of scAVV9/SUMF1. Importantly, our results indicate that benefits are achieved even when scAAV9/SUMF1 gene therapy is given at a more advanced period of the disease course. In addition, preclinical safety of either IT or ICM injection of scAVV9/SUMF1 was demonstrated in a GLP rat toxicology study up to a dose of 4.8 × 1012 vg per rat (human equivalent dose of ~2.4 × 1015 ICM per human). It is noteworthy that minimal to mild histology DRG toxicity was observed in the rats with no clinical correlate, consistent with other recent studies, supporting the use of rats to model this known toxicity of AAV940,41. Overall, the preclinical efficacy and safety studies reported herein support future consideration of this treatment approach for patients with MSD

Responses