Preparation of unsaturated MIL-101(Cr) with Lewis acid sites for the extraordinary adsorption of anionic dyes

Introduction

Water is vital for life on Earth, and its quality is crucial for water security, supply, and treatment1. However, with the growth of cities and increased activities that introduce contaminants, ensuring water safety has become increasingly important2. One issue is the discharge of large volumes of organic dye effluent, causing significant global problems3. These anionic dyes, commonly found in industrial wastewater, profoundly impact the environment and living systems because they are difficult to degrade using conventional methods4. Acid Blue 92 (AB-92), Acid Blue 90 (AB-90), and Congo red (CR) are examples of anionic dyes that are extensively used in various industries, including textiles and pharmaceuticals5. Discharging these dyes into water bodies can harm the environment and aquatic life6. They hinder sunlight penetration, reduce photosynthetic efficiency in marine plants, and disrupt the ecological balance of aquatic ecosystems3. In addition, cationic dyes in wastewater pose significant risks due to their carcinogenic effects on humans and aquatic organisms. Discharging synthetic dyes, particularly azo dyes, into water sources is a growing concern. These dyes are classified as micropollutants and can have mutagenic and toxic properties, thus posing a threat to public health. Therefore, prompt action is needed to address this issue.

Therefore, the adsorption of organic dyes has gained attention as an efficient and cost-effective method7. Adsorption offers flexibility in design and operation, making it a viable option for removing organic dyes8. A wide range of adsorbent materials, such as activated carbon, inorganic compounds, and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), have been used to remove organic dyes from water8,9,10,11. It is worth mentioning that adsorption techniques using MOFs offer several benefits in pollutant removal: simplicity of design, high adsorption capacities, and removal efficiency12,13,14,15.

Among several chromium-based MOFs, MIL-101(Cr) is recognized for its exceptional adsorption capabilities, particularly in water treatment applications16. Its large surface area, high porosity, presence of unsaturated Cr sites, and exceptional water, chemical, and thermal stability enable the effective removal of organic contaminants, such as dyes, phenols, and pharmaceuticals, from aqueous solutions16,17,18. During MIL-101(Cr) traditional synthesis, hydrofluoric acid (HF), an acid modulator, is often added19. This serves a few purposes: (i) increasing the specific surface area and pore volume, thus creating more sorption sites by causing missing linkers, (ii) influencing the nucleation behaviors, and (iii) effectively controlling the crystallization process and particle size20. Although these benefits, the use of HF poses significant health and safety risks due to its highly toxic and corrosive nature. Researchers have actively sought alternative synthesis methods that do not rely on this toxic acid21. Recently, nitric acid and acetic acid have been used instead of HF, which significantly increases the yield of MIL-101(Cr), improves safety, and simplifies the synthesis process22. Despite the advancements in HF-free synthesizing MIL-101(Cr), the literature reveals significant gaps, particularly regarding the specific role of Lewis acid sites in the dye adsorption process5. Additionally, existing methods often face challenges such as low reproducibility, limited scalability, and the potential degradation of the framework under operational conditions, highlighting the need for improved synthesis strategies and a deeper exploration of the MIL-101(Cr) adsorption properties.

More studies are needed to remake the role of unsaturated Cr sites in MIL-101(Cr) for the efficient adsorption of anionic dyes in different polluted systems. Therefore, MIL-101(Cr) was synthesized hydrothermally without HF and activated by vacuum drying at 140°C. The adsorbent was thoroughly characterized and employed as an efficient and ultra-rapid adsorbent for anionic dye removal. Furthermore, the adsorption selectivity for different dye classes and the influence of various adsorption parameters, such as adsorbent dose, pH, temperature, dye concentration, reusability, and salinity, on the adsorption of anionic dyes onto MIL-101(Cr) were investigated. The adsorption studies revealed that MIL-101(Cr) exhibits superior adsorption for anionic dyes compared to cationic dyes. The adsorption process was also confirmed through characterization. After conducting a study on a single dye-polluted system, binary, tertiary, and column-polluted systems, as well as different natural waters polluted with anionic dyes, were also examined to assess the scalability of MIL-101(Cr)‘s adsorption power towards anionic dyes. This study provides a new perspective on using MIL-101(Cr) for multiple adsorption systems of anionic dyes, potentially leading to practical solutions for anionic dye effluents in the textile and dye industries.

Methods

Chemicals

All chemicals were used as received without additional purification. Chromium nitrate nonahydrate (Cr(NO3)3.9H2O, 99% A.R.), terephthalic acid (BDC, 99% A.R.), sodium chloride (NaCl, 99% A.R.), dimethyl formamide (DMF, 99% A.R.), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98% A.R.), dichloromethane (CH2Cl2, 99% A.R.) were purchased from were bought from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Ethanol (EtOH, 99% A.R.) was purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Acid Blue 92 (AB-92, 95% A.R.) was bought from TCI Co. Ltd. Acid Blue 90 (AB-90, 95% A.R.), Congo red (CR, 98% A.R.), and Rhodamine B (RhB, 97% A.R.) were purchased from Macklin Co. Ltd. The chemical structures, molecular size, and other information on dyes under investigation are presented in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2.

Characterization methods

The phase purity and crystal structure of the prepared MIL-101(Cr) nanoadsorbent were analyzed using Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD, 1004967Q, UK) with CuKα radiation source (λ = 1.5418 Å) and with a scanning speed of 2Ɵ ◦/min. The function groups of MIL-101(Cr) were investigated using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FTIR, Nicolet-iS50, USA), and the spectrum was recorded in the 4000–400 cm−1 using KBr pellets. The thermal property was analyzed using a thermogravimetric analyzer (TGA, TA-Q500, USA) in the 50–800 °C temperature range with a rate of 10/°C under N2. The morphology and ultrastructure were studied by scanning electron microscope (SEM, HT-SU8010, Japan) attached with an energy dispersive spectrometer (Oxford X-max80) for elemental composition and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, HT-7820, Japan). Temperature-programmed desorption of ammonia (TPD-NH3, AutoChem1 II 2920, BelCata II, Japan). The Cr3+ ions leaching from MIL-101(Cr) during the adsorption test in the water was conducted using an Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass spectrometer (ICP-AES), PerkinElmer-NexION 2000, USA. X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) of MIL-101(Cr) were followed on thermo scientific ESCALAB 250Xi, with an X-ray energy of 1486.6 eV, a pass energy of 20 eV, and a step energy of 0.05 eV. N2 adsorption-desorption analysis at 77 K was measured on Quantachrome, AUTOSORB-1-C, USA, to find N2 isotherms, surface area, and pore properties. The dye concentration uptake over MIL-101(Cr) was determined using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (HITACHI, U2900, Japan). The molecular size of dyes was calculated using PyMOL Stereo 3D Zalman software.

Synthesis of MIL-101(Cr)

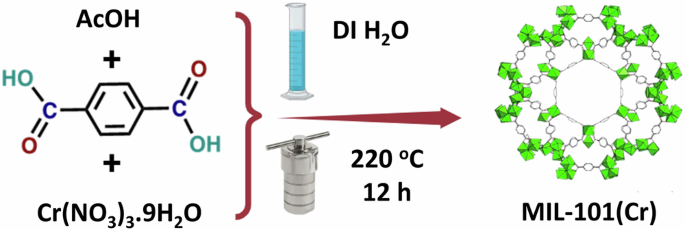

The scalable processing of MIL-101(Cr) is displayed in Fig. 1. Typically, (3.3225 g, 20 mmol) of BDC, (1.2010 g, 20 mmol) of AcOH, and (8.0058 g, 20 mmol) of Cr (NO3)3.9H2O were dissolved in 120 mL of DI water, moved to a 150 Teflon-lined autoclave, and heated for 12 h at 220 °C. The obtained green precipitate was separated from the mother solvent and washed once by DMF (100 mL: 7000 rpm/min) to remove unreacted BDC, followed by three times with EtOH (100 mL: 7000 rpm/min) to remove other soluble ions. The residue was dried in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h and named MIL-101(Cr) with a yield of 4.5369 g. The activation steps are as follows: MIL-101(Cr) was heated in 250 mL of CH2Cl2 at 40 °C for 12 h. Later, it was centrifuged and dried in a vacuum oven at 140 °C for 12 h. For the comparison purpose, a synthesized batch was synthesized as follows: 0.4001 g (1.000 mmol) of Cr (NO3)3.9H2O, 0.1660 g (1.000 mmol) of BDC, and 0.06 g AcOH were dispersed in 25 mL of DI. The washing, activation, and drying steps are the same in the case of a scalable batch. Also, it is named synthesized MIL-101(Cr). The adsorption experiments were performed using the gram-scalable MIL-101(Cr) sample.

A schematic illustration for MIL-101(Cr) preparation.

Adsorption experiments

Experiment design

Typically, 30 mg of MIL-101(Cr) was added to 50 mL of AB-92 (80 mg/L) and stirred at 500 rpm at 25 ± 2 °C for 60 min. A series of adsorption experiments, including MIL-101(Cr) dose, [AB-92], temperature, salt, and pH are investigated. The MIL-101(Cr) dose varied between 10 to 70 mg, while the [AB-92] was 60 to 100 mg/L. Besides, the effect of temperature was studied in the range of 288 K to 318 K. The adsorption process was investigated over a pH range of 4 to 10 using a universal buffer solution with a 0.04 mol/L concentration. After an interval of time, the supernatant was separated by 0.45 μm PVDF (treated first with AB-92 solution) and measured via UV–Vis spectrophotometer. The same experiments are conducted in the case of AB-90 dye with a change MIL-101(Cr) dose between 10 and 50 mg, while the [AB-90] was 5 to 10 mg/L. The adsorption capacity (Eq. 1) and removal efficiency (R; %) (Eq. 2) of MIL-101(Cr) were calculated using these equations. The absorbance calibaration curves of AB-92 and AB-90 dyes are shown in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Where ({{rm{q}}}_{{rm{t}}}) is the adsorption capacity (mg/g), C0, and Ct (mg/L) denote initial dye concentration and dye concentration at a time. The mass of the adsorbent is m (g), and the volume of the solution is V in (L).

Adsorption isotherms

Adsorption isotherm models determine the mechanism, characteristics, and interaction between adsorbate and adsorbent23. The experimental results were analyzed by using three isotherm models, namely the Langmuir model (Eq. 3), Freundlich model (Eq. 4), and Dubinin-Radushkevich (D-R) model (Eq. 5). Where the equation for each model is as the following:

Where Ce is the dye concentration (mg/L) at equilibrium, qe is the adsorption quantity at equilibrium (mg/g), qmax is the maximum adsorption capacity (mg/g), kL is the Langmuir isotherm constant (mg/g), n is a dimensionless Freundlich constant with a value range from 1 to 10 and refers to adsorption intensity, kF is the Freundlich constant (mg/g), qs (mg/g) is the theoretical adsorption capacity calculated from the D-R isotherm, and β is a constant of adsorption free energy (mol2/kJ) for each molecule adsorbed and given by (Eq. 6()). Where ε is the polanyi adsorption potential (kJ/mol) that is provided by (Eq. 7). E is the sorption energy, identifying the adsorption process as chemisorption when E > 40 kJ/mol and physisorption when E < 40 kJ/mol.

Adsorption kinetics

To gain a deeper understanding of the adsorption mechanism for anionic dyes onto MIL-101(Cr). Three linear kinetic models were used to analyze the experimental results. Namely, pseudo-first-order (PFO) (Eq. 8)24, pseudo-second-order (PSO) (Eq. 9)25, and intra-particle diffusion (IPD) (Eq. 10)26. The linear equations of three kinetic models are expressed as follows:

Where qe, qt, and qth are the adsorption capacities of the adsorbent at equilibrium, at a time, and experimentally, respectively. k1, k2 and ki are the rate constants related to the PFO, PSO, and IPD steps. C is the intercept constant.

Adsorption thermodynamics

The impact of temperature on the absorption of dyes was examined at four different temperatures, namely 288 K, 289 K, 308 K, and 318 K. Thermodynamic values, including the change in enthalpy (ΔH°), entropy (ΔS°), and Gibbs free energy (ΔG°), were calculated from (Eqs. 11, 12). Van’t Hoff’s plot (ln Kd vs. 1000/T), ∆S°, and ∆H° were obtained from the intercept and slope27,28,29.

Where Kd (qe/ce) is the adsorption equilibrium constant, R is the ideal gas constant (8.314 J/mol.K), and T is the absolute temperature (K).

Results and discussion

Characterization

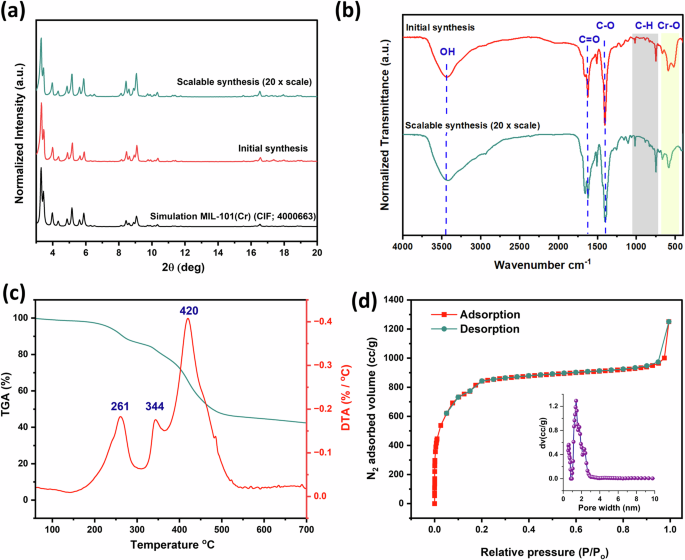

Figure 2a displays the PXRD patterns of the prepared MIL-101(Cr) samples, showing intense peaks that indicate the presence of abundant pores in the material’s structure and a well-defined crystalline structure, confirming the successful formation of MIL-101(Cr)19. The PXRD pattern shows distinct peaks at 2θ values of 5.82°, 8.41°, 9.10°, and 16.50°, which align with the literature values for MIL-101(Cr) and are in good agreement with the reported PXRD data30,31. Additionally, the crystal structures of the prepared MIL-101(Cr) were similar to the simulated MIL-101(Cr) (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, MIL-101(Cr) synthesized on a gram scale has the same peaks and typically matches the initially synthesized MIL-101(Cr) and the reported literature’s crystal structure30,31.

a PXRD patterns and b FT-IR spectra for both MIL-101(Cr) samples. c TGA-DTA curves, and d N2 adsorption–desorption at 77 K for MIL-101(Cr).

The FTIR spectra of the initial and scalable synthesized MIL-101(Cr) nanoadsorbent coincided with the literature30,32. As shown in Fig. 2b, the stretching vibrational band of the Cr-O bond was observed at 520 cm−1. Meanwhile, the monosubstituted band of the BDC benzene ring appeared at 590 and 755 cm−1, associated with C-H vibrations. Also, a strong symmetric vibrational band corresponding to the O-C-O single bond of the benzene ring is observed at 1400 cm−1. In addition, a sharp stretching vibrational band at 1624 cm−1 confirms the reaction between the Cr3+ ion and the COO− groups33. Also, the purity of MIL-101(Cr) from unreacted BDC was confirmed by the absence of an observed peak at around 1670 cm−1 34. For comparison purposes, no significant change in the FTIR spectra of the synthesized MIL-101(Cr) was observed, confirming that the gram-scale synthesis of MIL-101(Cr) has the same structural properties as the synthesized MIL-101(Cr).

Furthermore, the prepared MIL-101(Cr) showed high thermal stability, as previously reported35. Figure 2c represents the TGA-DTA curve of MIL-101(Cr), which has two weight losses. The first is before 300 °C (11.60%) and is attributed to the loss of moisture, which is physically held on the surface and trapped in the cage. The second is after 300 °C (41.77%) and coincides with the decomposition of the MIL-101(Cr) framework. Thus, MIL-101(Cr) can be used as a nanosorbent for practical water treatment due to its good thermal stability. Estimates of the specific surface area (SBET) and pore size properties of MIL-101(Cr) were determined by using BET analysis. The N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms for MIL-101(Cr), including the pore distribution curve, are described in Fig. 2d. The N2 isotherm plot for MIL-101(Cr) is fully reversible. It exhibits a typical type-I without hysteresis loops, which matches the presence of both types of microporous windows36. The SBET of MIL-101(Cr) was 3005.52 m2/g, which shows the potential of prepared MIL-101(Cr) in water treatment. In addition, it had a pore volume of 1.361 cc/g and an average pore diameter of 2.574 nm. Also, this suggests that MIL-101(Cr) has a microporous structure that may be advantageous in the adsorption of organic dyes.

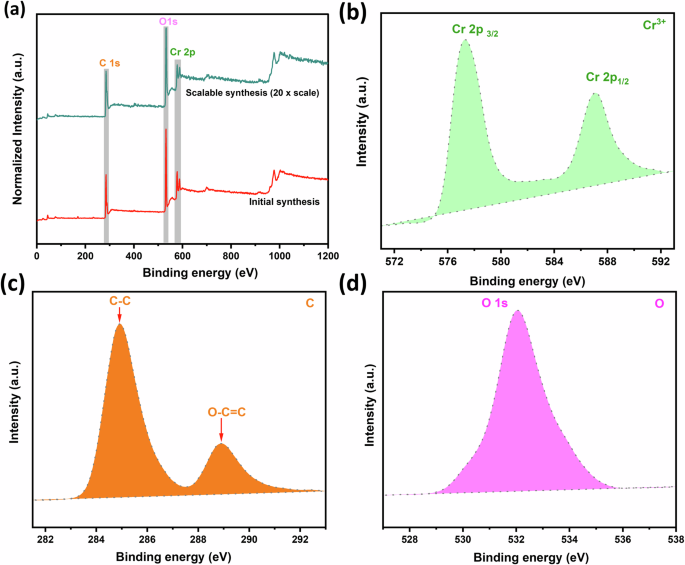

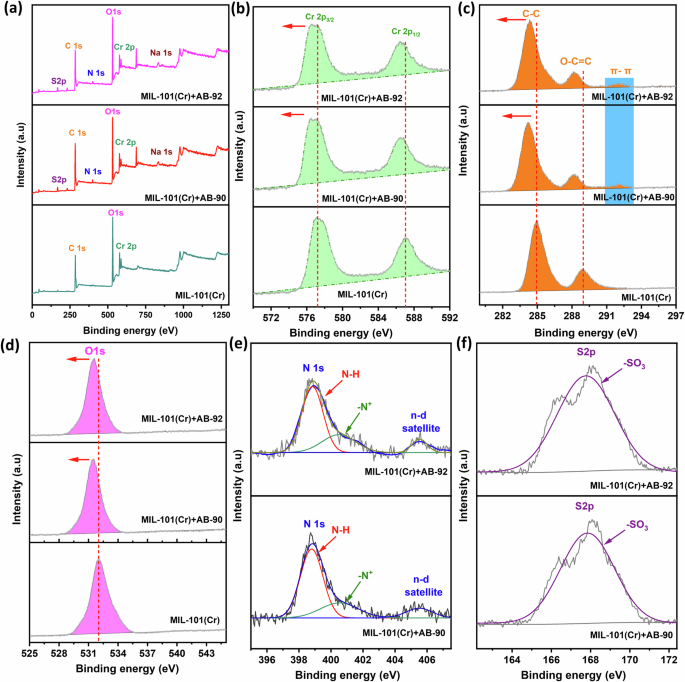

Figure 3 shows an XPS spectra survey of MIL-101(Cr), which is similar to the XPS pattern of reported MIL-101(Cr)37. Typically, the wide scan survey (Fig. 3a) records three emission peaks associated with the three elements, Cr, C, and O, which match the chemical composition of the MIL-101(Cr). Also, the same peaks were recorded in the case of scalable synthesized MIL-101(Cr) without shifting in the position of the peaks, confirming that the enlarged synthesis of MIL-101(Cr) on a gram scale using an AcOH as an acid modulator remains the crystal structure of MIL-101(Cr) without a change in the chemical composition. Meanwhile, a high-resolution scan of Cr 2p (Fig. 3b) recorded two major peaks, 577.28 eV for Cr 2p3/2 and 587.43 eV for Cr 2p1/2, which were assigned to Cr3+. In addition, Fig. 3c represents the high resolution of the C 1 s, showing two characteristic peaks assigned to carbon atoms in the BDC linker. The binding energies of these peaks are 284.89 eV for the C-C bond and 288.98 eV for the O-C = O bond. In addition, the high resolution of the O1s records a peak of 532.04 eV, as shown in Fig. 3d.

a XPS wide scan spectra of MIL-101(Cr) and b–d High resolution of Cr 2p, C 1s, and O 1s, respectively.

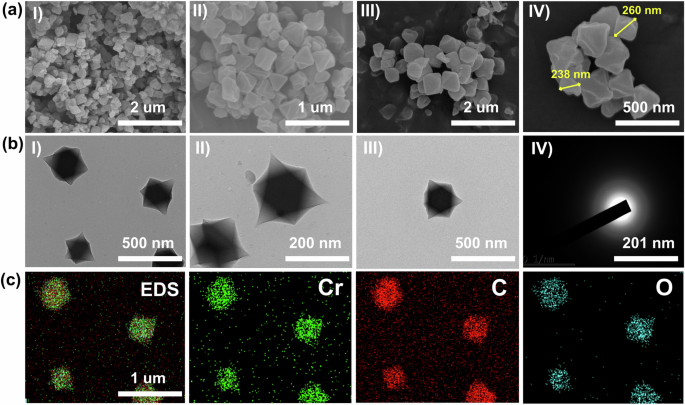

SEM and TEM images of MIL-101(Cr) are revealed in Fig. 4a. The morphology of MIL-101(Cr) was a regular octahedron crystal with a smooth surface and a crystal size of approximately 230–270 nm (Fig. 4a, IV). More information on the morphology was obtained from the TEM analysis. MIL-101(Cr) discrete octahedral crystals as shown in Fig. 4b. Moreover, Fig. 4bIV shows the low diffraction rings in the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern, indicating that the prepared MIL-101(Cr) is polycrystalline material, coinciding with the PXRD results. On the other hand, EDS analysis (Fig. 4c) shows that all Cr, C, and O elements were dispersed well through the MIL-101(Cr) structure.

The figure shows a SEM, b TEM, and c EDS analysis of MIL-101(Cr).

Adsorption performance of MIL-101(Cr)

Recently, synthesis of MIL-101(Cr) without HF additive as a potential adsorbent for addressing water pollution has emerged and become more viable for industrial-scale dye removal. The present study aims to produce MIL-101(Cr) hydrothermally on a gram scale without adding HF as a modulator to obtain an environmentally friendly adsorbent. Then, it was applied to remove anionic dyes (AB-90, AB-92, CR) that differ in their structure, specifically in the number of SO32- and electronegativity atoms. In addition, we investigated the relationship between their structures and the effect on the adsorption capacity of MIL-101(Cr). For this purpose, various adsorption parameters such as dose, temperature, solution pH, dye concentration, pollutant selectivity, and reusability are investigated. Also, it is applied in different anionic dyes in polluted systems, including single, binary, ternary, and various natural water.

Effect of MIL-101(Cr) dose

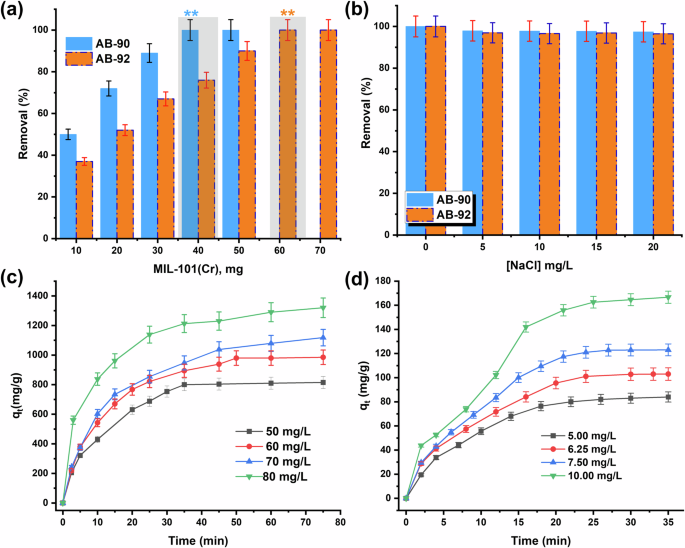

The effect of MIL-101(Cr) dose on the R (%) of AB-90 and AB-92 dyes is displayed in Fig. 5a. As shown in Fig. 5a, the R (%) initially increases with an increase in MIL-101(Cr) dose in the range of (10–50 mg) in case of AB-90 and (10–70 mg) in case of AB-92. The number of adsorption sites introduced increases with increasing dose27. In addition, after a certain dose, the R (%) reaches a constant value. Therefore, 40 mg was considered the optimal dose for 100% removal of 5 mg/L AB-90 dye within 30 min, while 60 mg was considered the optimal dose for 100% removal of 80 mg/L AB-92 dye within 60 min.

a Effect of MIL-101(Cr) dose, b effect of NaCl salt, c effect of [AB-92], and d effect of [AB-90] on the adsorption of dyes over MIL-101(Cr).

Effect of salt

Textile dyeing wastewater contains strong electrolytes (i.e., NaCl)38. Therefore, the study of the effect of ionic strength is an important indicator in the adsorption process. Typically, NaCl concentrations are studied in the 5–20 mg/L range in aqueous solutions. It is completely ionized into Na+ and Cl− ions, which compete with the dye molecules. According to Fig. 5b, a slight decrease in removal rate, mostly negligible, was observed when both dyes were adsorbed on MIL-101(Cr). This effect is insignificant and returns to some competitive adsorption mainly due to the salting-in and salting-out between the dye molecules and MIL-101(Cr)39. In addition, the negative effect of salt is considered an advantage for MIL-101(Cr) as an adsorbent in practical wastewater treatment.

Effect of dye concentration

Different [AB-90] levels in the 5–10 mg/L range and [AB-92] in the 50–80 mg/L range were studied, and other parameters were held constant. The absorption results are shown in Fig. 5c, d. MIL-101(Cr) adsorption capacity for both dyes increased with increasing concentration. This phenomenon is due to the increased affinity between the dye molecules and the adsorption sites on the surface of MIL-101(Cr) until equilibrium is reached40. Furthermore, in the case of AB-92, the qe of MIL-101(Cr) was higher than that of AB-90, with values of 1330 mg/g and 170 mg/g, respectively. This implies that the SO32- group in the dye structure has a major role and is adsorbed/bonded through the electrostatic/coordination interactions between the unsaturated Cr3+ sites of MIL-101(Cr) and the SO32- groups of dye molecules. As a result, AB-92 adsorbed with high quantities on MIL-101(Cr) compared to AB-90.

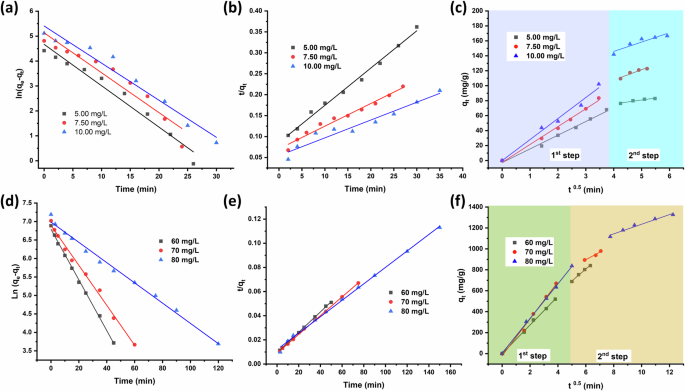

The adsorption kinetics models, namely PFO, PSO, and IPD, are used to study the adsorption mechanism of adsorbents. Consequently, the obtained experimental results in this study are applied to three kinetic models (Fig. 6), and the adsorption type and process are analyzed according to the fitting results. The PFO model is commonly defined by physical adsorption, while the PSO model refers to chemisorption, which typically involves electron interactions or exchange41. The data for the fitting of each adsorption kinetic model is presented in Table 1. The correlation coefficient (R2) for PSO is close to 1 and higher than in the case of PFO. This indicates that the adsorption of both anionic dyes over MIL-101(Cr) fits the PSO model and relies on chemisorption. Furthermore, the qe determined by the PSO model closely corresponds to the qt observed in the experiment. This indicates that the adsorption process fits well with the PSO model.

The figure shows the PFO, PSO, and IPD kinetic models for the adsorption of AB-90 (a–c) and AB-92 (d–f) over MIL-101(Cr), respectively.

The IPD model is commonly employed to elucidate the adsorption process’s rate-controlling step and diffusion mechanism5. Table 2 represents the IPD model fitting results. In this study, the adsorption process of anionic dyes over MIL-101(Cr) is controlled by two stages (Fig. 6c, f). The first step is a significantly rapid adsorption rate due to strong chemisorption between the dye function groups and the surface of the MIL-101(Cr). In the second step, the dye concentration decreased, followed by a decline in the adsorption rate due to the intramolecular diffusion of dyes into the pores of MIL-101(Cr).

Effect of pH

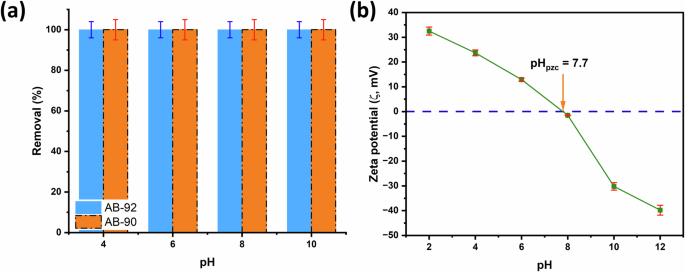

The pH of the solution significantly affects the adsorption of anionic dyes, such as AB-90 and AB-92, on the surface of MIL-101(Cr). We investigated the adsorption performance of MIL-101(Cr) with respect to dyes AB-90 and AB-92 across a pH range of 4 to 10. A universal buffer solution with a concentration of 0.04 mol/L was used. The experiment involved immersing 20 mg of MIL-101(Cr) into a 5 ml solution of AB-90 (50 mg/L, pH 4, 25 °C) in a Pyrex tube (20 mL) and stirring it for 1 h to achieve complete adsorption. The AB-90 supernatant was then separated, and the concentration of the remaining AB-90 was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The same procedure was repeated with the AB-92 dye but with a MIL-101(Cr) dose of 30 mg and an AB-92 concentration of 80 mg/L. Additionally, we performed the same procedure with the AB-90 and AB-92 dyes at pH values of 6, 8, and 10. Figure 7a illustrates the effect of the solution’s pH on the R% of AB-90 and AB-92 dyes on MIL-101(Cr). As depicted in Fig. 7a, the removal rate for both dyes is approximately 100%, with no significant reduction as the pH increases from 4 to 10. Therefore, this study’s prepared MIL-101(Cr) demonstrates effective industrial wastewater treatment across a wide pH range.

a The effect of pH on the adsorption of dyes and b zeta potential of test for MIL-101(Cr) at different pHs.

In addition, zeta potential (ζ, mV) measurement was performed to determine the surface charge of the synthesized MIL-101(Cr), which could enhance our comprehension of the probable adsorption mechanisms. ζ analysis is measured at different pH levels, and the results are shown in Fig. 7b. The charge on the adsorbent is pH dependent. The point of zero charges is the pH value at which the zeta potential becomes zero (pHPZC). When the pHPZC exceeds the pH, the adsorbent carries a positive charge. Conversely, when the pHPZC is less than the pH, the adsorbent carries a negative charge42. Here, pHPZC is 7.7, and the charge on MIL-101(Cr) is positive and after it is negative. Therefore, at lower pH values, the surface of MIL-101(Cr) is positively charged, which enhances its adsorption ability towards AB-90 and AB-92 anionic dye molecules due to electrostatic attraction. Against the odds, at high pH, the R% is still constant, and this is my attribute to coordination interactions between unsaturated Cr3+ sites of MIL-101(Cr) and the undissociated form of anionic dyes5. This is added to the hydrogen bonding formation between the electronegative atoms of dyes and the OH group of MIL-101(Cr). Furthermore, π-π stacking between MIL-101(Cr) benzene rings and dyes43,44. The adsorption study at pH 2 and 12 is avoided because the dye changed its colors at these values (Supplementary Fig. 4).

In DI water, there are very few ions present, so MIL-101(Cr) has a ζ of 33 mV, and the anionic dyes have negative charges. Thus, strong electrostatic interactions between the surface of MIL-101(Cr) and dyes are responsible for the fast adsorption rate of the dyes at mild conditions. Conversely, at pH 7 (buffer solution), more OH ions are present, which alters the surface charge45 of MIL-101(Cr) and consequently changes the measured ζ value of MIL-101(Cr) to 6.65 mV. However, it still has a positive charge, resulting in MIL-101(Cr) attaching to anionic dyes with a slightly lower adsorption rate than DI water.

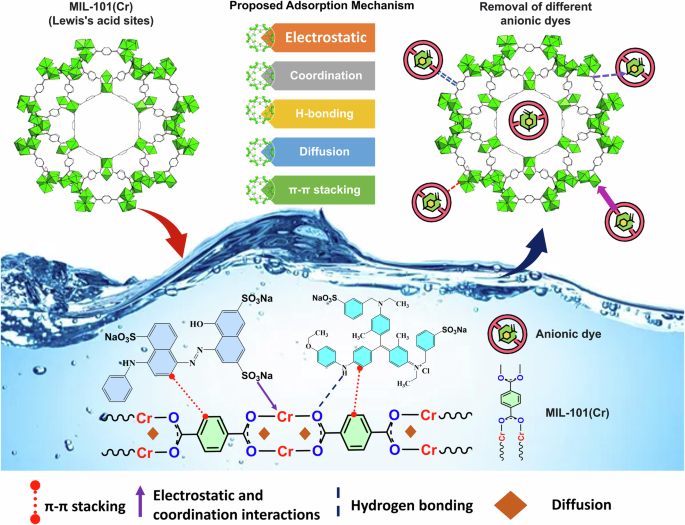

In summary, the proposed adsorption mechanisms for efficient removal of anionic dyes over MIL-101(Cr) are depicted in Fig. 8 in which the electrostatic interaction defined the adsorption process at lower pH, whereas other adsorption forces at higher pH. Therefore, effectively removing anionic dyes over a broad pH range of 4–10 is a key benefit of using MIL-101(Cr), such as adsorbents for effective dye removal from textile wastewater.

Schematic illustration for the proposed adsorption mechanisms.

Effect of temperature

Studying temperature and thermodynamics in the adsorption process is crucial for enhancing the performance of the MIL-101(Cr) adsorbent and identifying its potential long-term applications in industrial wastewater treatment. In addition, the thermodynamic factors aid in determining the spontaneity of the adsorption process. We computed and presented the thermodynamic parameters of adsorption in Table 3 to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the interaction between AB-90 and AB-92 dyes and the surface of MIL-101(Cr) adsorbent. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 5a, c, the adsorption capacity of AB-90 and AB-92 dyes decreases with increasing temperature, respectively. This indicates that the adsorption process is exothermic. The obtained thermodynamic parameters (Table 3) show that ΔG° for both dyes are negative, suggesting spontaneous adsorption processes. As the temperature increases, the ΔG° values decrease, decreasing the likelihood of adsorption at higher temperatures. Furthermore, the ΔG° values for AB-92 are more negative than those of AB-90, suggesting that AB-92’s adsorption onto MIL-101(Cr) is more favorable46, consistent with the removal results. The negative values of ΔH° for both dyes suggest an exothermic nature characterizes the adsorption process and is consistent with the literature5. The ΔS° were determined to be negative for both dyes, indicating a reduction in the level of disorder/randomness at the solid/liquid interface between the MIL-101(Cr) and the dye solution. This is likely due to the AB-90 and AB-92 dye molecules becoming more ordered and structured on the MIL-101(Cr) surface compared to their random distribution in the aqueous solution and that no significant changes occurred in the structure of the adsorbent and the adsorbate during the adsorption process47.

Multi-pollutant systems and dye selectivity

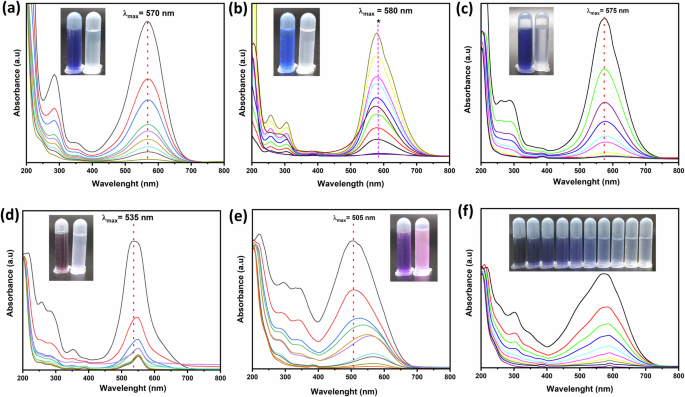

Studying the effect of dye selectivity is crucial for developing efficient and environmentally friendly methods for removing specific dyes from wastewater. Various industries, including textiles, commonly use anionic dyes, which, if improperly treated, can cause significant environmental harm48. The selectivity of the removal process ensures that these dyes are effectively targeted and removed, minimizing their release into the environment. On the other hand, the simultaneous removal of multiple dye pollutants from wastewater effluents is crucial for effective water treatment and environmental protection, which improves water quality and protects ecosystems49. In this study, AB-92, CR, and AB-90 from the anionic dye type and RhB from the cationic dye type were selected to study the ability of MIL-101(Cr) adsorption selectivity for a specific dye in a single and binary polluted system. In the binary-polluted system, the mixture of dyes was as follows: (AB-92 + AB-90), (AB-92 + CR), and (AB-92 + RhB), respectively. Meanwhile, in the tertiary-polluted system, the dye mixture was as follows: (AB-92 + AB-90 + CR). For each dye-polluted system, Fig. 9 shows the decrease in absorbance of dyes with time. As illustrated in Fig. 9a–d, f, 100% removal was achieved for a single dye solution of AB-92 and AB-92 within 60 and 45 min, respectively, and for a binary mixture of (AB-92 + AB-90) within 45 min and (AB-92 + CR) within 50 min, as well as for a tertiary system (AB-92 + AB-90 + CR) within 35 min. This may return to the electrostatic interaction between negative anionic dyes and positively charged MIL-101(Cr) at normal conditions. In contrast, a binary mixture of (AB-92 +RhB) achieved 88% removal after 120 min. This is due to some RhB dye remaining because of the repulsion between it and MIL-101(Cr) (Fig. 9e). Considering the aforementioned R% values, MIL-101(Cr) showed higher selectivity and efficient adsorption towards anionic dyes than cationic dyes. In addition, it has a significant removal efficiency for multiple anionic pollutant systems. Therefore, the prepared MIL-101(Cr) offers a novel, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly approach to removing many anionic dyes.

The decrease of absorbance with time for a AB-92 [30 mg, 80 mg/L, 25 °C, 60 min], b AB-90 [20 mg, 5 mg/L, 25 °C, 45 min], c binary (AB-92 + AB-90) [25 mg, 80 mg/L, 5 mg/L, 25 °C, 45 min], d binary (AB-92 + CR) [25 mg, 80 mg/L, 20 mg/L, 25 °C, 50 min], e binary (AB-92+RhB) [25 mg, 80 mg/L, 5 mg/L, 25 °C, 120 min], and f tertiary (AB-92 + AB-90 + CR) [25 mg, 40 mg/L, 5 mg/L, 10 mg/L, 25 °C, 35 min]. All the experiments were in a Pyrex tube (50 mL).

Adsorption performances in natural water and household water purifier filter

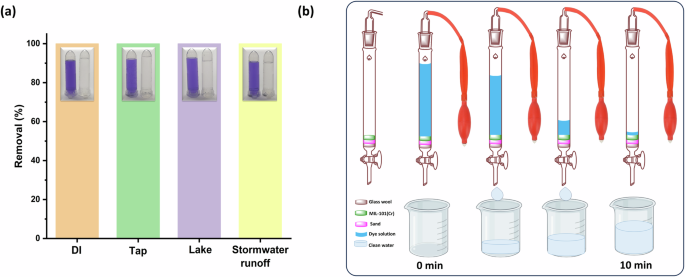

The adsorption characteristics of several adsorbents are significantly limited in natural water due to diverse cations, anions, and dissolved organic matter (DOM)50. To study the possible use of MIL-101(Cr) for removing anionic dye contaminants, we examined how well MIL-101(Cr) adsorbs AB-92 in different water samples (tap water, Lake water, and stormwater runoff). In a Pyrex tube (100 mL), 15 mg was mixed with 50 mL of 60 mg/L of AB-92, prepared using DI, tap, Lake, and stormwater runoff waters, respectively, and stirred for 30 min at 25 ± 2 °C. After that, the AB-92 supernatant was separated, and its concentration was measured on a UV–Vis spectrophotometer. Figure 10a demonstrates that MIL-101(Cr) achieves 100% removal of AB-92 in different water samples with a high concentration of 60 mg/L within 30 min. The adsorption rate of MIL-101(Cr) towards AB-92 in simulated polluted water mixed with natural water was slower than that in DI, as anticipated. Nevertheless, MIL-101(Cr) can effectively AB-92 from different natural water. This suggests the prepared MIL-101(Cr) is a highly suitable adsorption material for future practical use.

a MIL-101(Cr) adsorption performance in different water samples. b A schematic of the column household water purifier packed with MIL-101(Cr).

To assess the adsorption capacity of MIL-101(Cr) for anionic pollutants, a household water purifier filter was designed by including MIL-101(Cr) as an adsorbent as the filtration medium with quartz sand to control water flow. In a 50 mL column (length 45 × 500 mm/24), 1.0 g of quartz sand was added to fill the space between the glass wool and the packed MIL-101(Cr) (0.17 g) as a simulated water purifier filter (Supplementary Fig. 6, Supplementary Video 1). Then, 50 mL of AB-90 (80 mg/L) was added to the column, and the dye solution started to move under the pressure pump (Fig. 10b). As shown in Fig. 10b, the effective treatment volume of the MIL-101(Cr) filter toward AB-90 (80 mg/L) was 50 mL, in which the removal efficiency could be achieved 100% within 10 min. The adsorption capability of the MIL-101(Cr) filter was exhausted up to 250 mL by adding another 50 of AB-90 and repeated 3 times. When compared to conventional water purification filters for purifying water contaminated with anionic dyes, MIL-101(Cr) shows a superior ability to remove anionic dyes, suggesting that the MIL-101(Cr) filler has great potential for purifying water contaminated with anionic dyes.

Recyclability and stability of MIL-101(Cr)

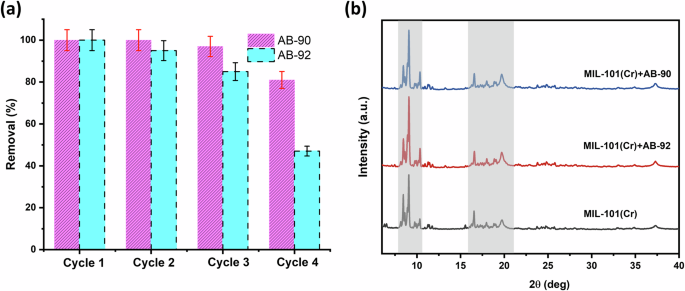

To validate the reusability of MIL-101(Cr), it was successfully separated by centrifuging the mixture after the adsorption process. Then, MIL-101(Cr) adsorbent was washed with DI water once, followed by EtOH four times, to remove the adsorbed anionic dyes. After that, it was dried at 70 °C in a vacuum oven, and the MIL-101(Cr) sample was reused for the next cycle. Individually, 20 mg of MIL-101(Cr) was added to 50 mL of AB-90 solution (5 mg/L) and 30 mg for AB-92 (80 mg/L) and kept stirring for 1 h at 25 °C. Next, we separated the supernatant of each dye, and it was measured using a UV-Vis device. We repeated the same procedures for three cycles. Figure 11a showed that MIL-101(Cr) exhibits good adsorption efficiency with a slight decrease in the removal efficiency from 100% to 80% for AB-90 and from 100% to 50% for AB-92 after four runs. The decrease in removal efficiency of AB-92 is due to the nature of its structure, which can still be attached to the MIL-101(Cr) surface through different interactions. As a result, normal washing methods may not effectively remove these groups. To further investigate, an XPS analysis was conducted on MIL-101(Cr) after AB-92 adsorption. The results revealed that AB-92 binds more strongly to the MIL-101(Cr) surface compared to AB-90. This is evident from the slightly greater shifts in binding energy observed in the XPS analysis. Therefore, it can be concluded that the dye molecule’s properties have an impact on its recyclability.

a Reusability of MIL-101(Cr) for the removal of anionic dyes and b PXRD spectra of MIL-101(Cr) before and after dyes adsorption.

Chemical and water stability also became important criteria for judging the quality of adsorbents during wastewater treatment51. Herein, MIL-101(Cr) samples were characterized by PXRD analysis after the adsorption of anionic dyes to investigate the changes in the crystal structure of MIL-101(Cr). Inferring from the PXRD patterns, MIL-101(Cr) maintained its main characteristic peaks after the adsorption of dyes (Fig. 11b), which confirms that MIL-101(Cr) has good chemical and water stability during the adsorption process. Also, ICP-AES indicated that less than 0.029 wt% and 0.15 wt% of Cr3+ ions from MIL-101(Cr) leached into the water after the last cycle of adsorption of AB-90 and AB-92, respectively. These results could prove that MIL-101(Cr) showed high chemical stability during adsorption.

Further studies were conducted to investigate the water stability of MIL-101(Cr). In this experiment, MIL-101(Cr) was immersed in water for one week. Subsequently, XRD and SEM analyses were performed. The XRD analysis (Supplementary Fig. 7) revealed that the crystal structure of the MIL-101(Cr) samples remained unchanged after the one-week immersion in water. There were no noticeable shifts or disappearances in the diffraction peaks, indicating that the crystal structure of the MOF was unaffected by the water exposure. The SEM analysis (Supplementary Fig. 8) showed that the octahedral shape characteristic of MIL-101(Cr) remained intact even after being immersed in water for one week. No visible alterations in particle size or shape were observed, suggesting that the material maintained its structural integrity throughout the water exposure. The results of the extended immersion test, as well as the subsequent XRD and SEM analyses, provide evidence of the excellent water stability of the MIL-101(Cr) material prepared in this study. These findings are consistent with previous research conducted on MIL-101(Cr) compared to other MOFs52.

Adsorption isotherm

Adsorption isotherms are crucial for describing how pollutants interact with adsorbents at the molecular level53. We used Langmuir, Freundlich, and the D-R isotherm models to fit the experimental data and determine the optimal adsorption isotherm for studying the removal of these anionic pollutants over MIL-101(Cr) (Supplementary Fig. 9). Table 4 presents the valuable adsorption isotherm parameters. Compared to other models, the Langmuir model provided a more accurate description of the adsorption process (R2 > 0.99), demonstrating the monolayer adsorption of AB-92, AB-90, and CR on the surface of MIL-101(Cr). Further, the calculated RL for these dyes is 0 < RL < 1, meaning that the MIL-101(Cr) is suitable for adsorbing these dyes. The maximum adsorption capacity (qmax) was 4231, 1266, and 568 mg/g for AB-92, CR, and AB-90, respectively. Table 5 lists these values and compares them with other reported results in the literature using different adsorbents. After comparing them, it’s clear that MIL-101(Cr) is much better at absorbing AB-92, CR, and AB-90 than other materials used to get rid of the same dyes. Additionally, the adsorption strength value 1/n can be used to assess the difficulty of the adsorption process in the following ways: irreversible adsorption if 1/n = 0, favorable adsorption if 0 < 1/n < 1, and unfavorable adsorption if 1/n > 154. In our case, the 1/n value for all dyes is 0 < 1/n < 1, indicating that the adsorption process of AB-92, AB-90, and CR on MIL-101(Cr) is easily and favorable to the heterogeneous nature of MIL-101(Cr). On the other hand, the sorption energy, as determined by the D-R isotherm, exceeded 40 kJ/mol for the adsorption of AB-92, AB-90, and CR on MIL-101(Cr). This suggests that the adsorption processes were of a chemical in nature according to the D-R assumption55.

Proposed adsorption mechanism

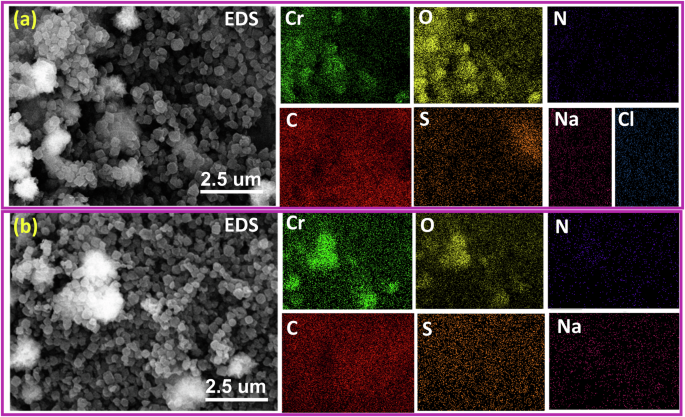

A range of characterizations were conducted to elucidate the adsorption mechanism of MIL-101(Cr) towards AB-90 and AB-92 dye. The PXRD patterns of MIL-101(Cr) after adsorption exhibited a high degree of similarity to the original MIL-101(Cr), indicating that the structure of MIL-101(Cr) was preserved during the adsorption process (Fig. 11b). After adsorption, the SEM of MIL-101(Cr) retained its integrated morphology, suggesting that MIL-101(Cr) had high water stability during the pollutant adsorption process (Fig. 12). To further explore the adsorption mechanism of MIL-101(Cr) toward towards AB-90 and AB-92 dye, EDS analysis was performed to investigate new elements after the adsorption process. Compared to EDS analysis for MIL-101(Cr) before adsorption (Fig. 4c), new elements are observed after adsorption, such as S, N, Na, and Cl for AB-90 (Fig. 12a), while S, N, and Na for AB-92 (Fig. 12b); added to increase in the concentration of C and O. These new elements are related to dyes structure indicating the AB-90 and AB-92 dye were adsorbed successfully on the MIL-101(Cr) surface.

The figure shows an elemental EDS mapping analysis for MIL-101(Cr) after adsorption of a AB-90 and b AB-92.

Further information about the adsorption mechanism for the removal of AB-90 and AB-92 dye onto MIL-101(Cr) was supported by XPS analysis after adsorption (Fig. 13). The wide survey XPS spectra of MIL-101(Cr) after adsorption of AB-90 and AB-92 dye (Fig. 13a) clearly shows new emission peaks associated with the three elements N 1 s, S 2p, and Na 1 s, indicating successful adsorption of AB-90 and AB-92 dye. The high-resolution Cr 2p, C 1 s and O 1 s spectra (Fig. 13b–d) clearly show lower shifting in the emission peaks, indicating a change in these atoms’ chemical environment in the MIL-101(Cr) structure after adsorption. This is due to the electrostatic interaction between positively charged MIL-101(Cr) and negatively charged dyes, and these results, combined with the PSO kinetic analysis model, suggest that the adsorption process is defined as chemisorption. Furthermore, the high-resolution C 1 s spectrum (Fig. 13c) revealed a new emission peak at 292 eV, corresponding to a π-π stacking interaction between the benzene rings of MIL-101(Cr) and the aromatic rings of dyes56. Thus, the π-π stacking interaction also defined the adsorption process in this study. Simultaneously, the high-resolution spectra for the MIL-101(Cr)+AB-90 and MIL-101(Cr)+AB-92 samples (Fig. 13e, f) revealed a new broad emission for the N and S elements, respectively, embedded with dye adsorption, at 399 eV and 167 eV. Figure 13 illustrates the fitting of broad N 1 s into two peaks, one at 399.6 eV attributed to amine-like (N-H) and another at 400.66 eV attributed to (N+) due to the hydrogen bonding interaction with the OH of the MIL-101(Cr) surface57. In particular, Fig. 13e showed a unique peak at 405 eV, which means that unsaturated Cr3+ sites in MIL-101(Cr) coordinated with the lone pair of N atoms in the dye structure through the n-d transition58. This means that the Cr3+ and N atoms formed coordination interactions. In addition, hydrogen bonds might form between the uncoordinated COOH of MIL-101(Cr) and the electronegative N atoms of dye in the form C = O⋅⋅⋅H-N50. Typically, the S 2p peak was observed in the high-resolution spectra for MIL-101(Cr)+AB-90 and MIL-101(Cr)+AB-92 samples (Fig. 13f) due to the electrostatic attraction between the negatively charged SO32- groups of the anionic dyes and the positively charged surface of the MIL-101(Cr). Based on the abovementioned, AB-90 and AB-92 dyes were absorbed effectively onto MIL-101(Cr), and adsorptive interactions could be described as electrostatic, coordination, hydrogen bonding, and π-π stacking interactions. There is a relationship between the dye’s molecular size and MOF’s pores during the adsorption process. In this study, we used PyMOL software (Supplementary Fig. 2) to measure the molecular size of three dyes and compared them to the pore size of MIL-101(Cr). The results showed that AB-92, AB-90, and CR have sizes of 11, 17.5, and 12.5 Å, respectively, which are all smaller than the average pore diameter of MIL-101(Cr) at 25.74 Å. Therefore, these dyes can easily be adsorbed inside the MIL-101(Cr) pores, and the adsorption mechanism may also involve pore diffusion. In summary, the adsorption of these dyes may be proposed to occur through electrostatic coordination, hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking interactions, and pore diffusion.

a The XPS-wide survey spectra of MIL-101(Cr) after AB-90 and AB-92 dye adsorption. High-resolution XPS spectra after adsorption of b Cr 2p, c C 1s, d O 1s, e deconvolution of the N 1s, and f deconvolution of the S 2p.

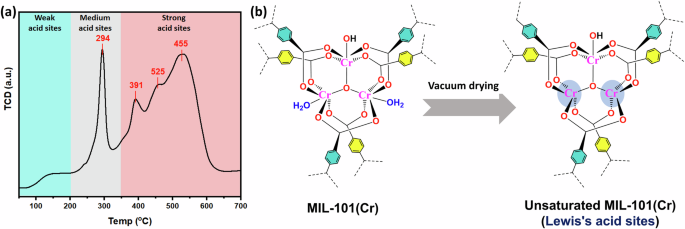

The TPD-NH3 analysis (Fig. 14a) of MIL-101(Cr) indicates the presence of two types of acid sites: medium acid sites associated with Lewis acid sites (LAS) and strong acid sites related to Brønsted acid sites (BAS)59,60. These acid sites play a crucial role in the adsorption of anionic dyes by facilitating coordination interactions between unsaturated Cr3+ sites and the lone pairs of electrons on oxygen atoms of anionic dyes. It enhances the adsorption rate of MIL-101(Cr) towards AB-92 and AB-90 dyes. Furthermore, the presence of LAS and BAS in MIL-101(Cr) supports the proposed adsorption mechanism, as it allows for the adsorption of anionic dyes through coordination and electrostatic interactions, respectively. Due to the presence of these acid sites obtained by vacuum drying (Fig. 14b) and the high surface area and porous structure of MIL-101(Cr), it is an efficient adsorbent for removing anionic dyes from aqueous solutions.

a TPD-NH3 analysis of MIL-101(Cr). b Schematic illustration for unsaturated Lewis’s acid structure of MIL-101(Cr).

In conclusion, an unsaturated MIL-101(Cr) was successfully prepared based on the approach of synthesizing an environment-friendly adsorbent to remove different anionic dyes and multiple-polluted wastewater as well as from different naturally polluted water. The MIL-101(Cr) has been methodically described utilizing several approaches. The exceptional adsorption capacity and rapid MIL-101(Cr) rate towards anionic dyes were verified, with AB-92 having the highest adsorption capability and CR and AB-90. The proposed adsorption mechanism involves electrostatic interaction, coordination, hydrogen bonding, π-π stacking, and pore diffusion. Overall, MIL-101(Cr) exhibits a higher affinity for adsorbing anionic dyes than cationic dyes. Furthermore, MIL-101(Cr) has effectively removed AB-92 from various natural waters. We recommend the large-scale preparation of unsaturated MIL-101(Cr) for future environmental remediation purposes.

Responses