Pressure-dependent magnetism of the Kitaev candidate Li2RhO3

Introduction

Honeycomb magnets with dominant Kitaev interactions are predicted to realize a spin-liquid state with emergent topological order and exotic excitations1,2. Material realizations of this scenario are usually searched for among the low-spin d5 compounds following the initial proposal by Jackeli and Khaliullin3. Whereas several honeycomb iridates and Ru3+ halides have been extensively studied experimentally4,5,6, rhodates remain relatively less explored despite the fact that Rh4+ is isoelectronic to Ir4+ and well suited for realizing Kitaev exchange.

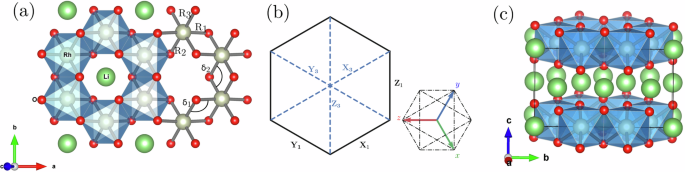

Lithium rhodate, Li2RhO3, features a slightly deformed honeycomb lattice of the Rh4+ ions7 (see Fig. 1). Its silver analog, Ag3LiRh2O6, can be prepared by an ion-exchange reaction8. Despite the rather similar structures of the honeycomb layer, these two compounds feature very different magnetic properties. Whereas the electronic state of Rh4+ in Li2RhO3 should be close to ({j}_{{rm{eff}}}=frac{1}{2}), akin to the typical Ir4+ compounds4, a departure from the ({j}_{{rm{eff}}}=frac{1}{2}) state has been detected in Ag3LiRh2O6 by x-ray spectroscopy8. Li2RhO3 evades long-range magnetic order, but reveals a change in spin dynamics associated with spin freezing below 6 K9,10, as confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance and muon spectroscopies11. By contrast, Ag3LiRh2O6 develops long-range antiferromagnetic order below 90 K8, which is the highest Néel temperature among the d5 honeycomb magnets reported to date. The differences between Li2RhO3 and Ag3LiRh2O6 are far more drastic than between the corresponding iridates, α-Li2IrO3 and Ag3LiIr2O6, that reveal rather similar magnetic behavior with the long-range magnetic order below 15 K12 and 8 K13, respectively. This comparison suggests that rhodates may be more tunable by (hydrostatic or chemical) pressure compared to the iridates.

a Rh-honeycomb layer along the ab-plane showing the two symmetry allowed Rh-O-Rh angles and the definition of the Rh-O bonds. b Definition of the local coordinate reference frame x, y, z, and the bonds of interest for first and third neighbors. c Stacking of honeycomb layers in the Li2RhO3 structure.

In the following, we explore this possibility and study pressure evolution of Li2RhO3. X-ray diffraction experiments on this compound revealed the structural phase transition with the formation of linear Rh4+ chains above 6.5 GPa at room temperature14. It means that Li2RhO3 offers a broader pressure window for tuning magnetism of the Rh4+ honeycombs than different polymorphs of Li2IrO315 that become nonmagnetic upon the structural dimerization transition already at 3.5–4.0 GPa at room temperature16,17,18,19,20 and at even lower pressures of 1.0–1.5 GPa on cooling21,22. Here, we probe Li2RhO3 using magnetization measurements under pressure and follow the evolution of individual magnetic couplings in this material using ab initio and cluster many-body calculations. Previous quantum-chemistry studies reported Kitaev exchange as one of the leading terms in the Li2RhO3 spin Hamiltonian at ambient pressure23.

Results

Magnetization under pressure

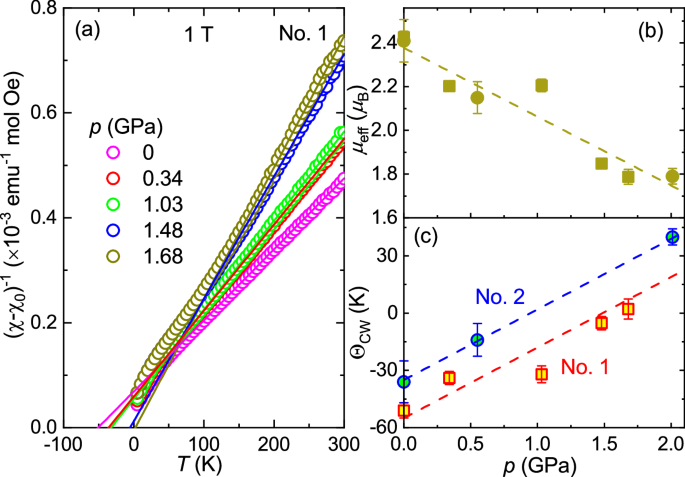

Figure 2a shows the inverse magnetic susceptibility H/M of Li2RhO3 measured as a function of temperature under various pressures. A temperature-independent term χ0, which stands for the residual part of the background from the pressure cell, has been subtracted for each pressure, respectively. At all pressures, the susceptibility monotonically increases upon cooling, similar to the ambient-pressure behavior reported in the literature9,11. The high-temperature part of magnetic susceptibility can be fitted with the Curie-Weiss law (solid lines), χ-χ0 = C/(T − θ), where C is the Curie constant and θ is the Curie-Weiss temperature.

a Temperature-dependent inverse dc magnetic susceptibility H/M of Li2RhO3 measured at various pressures from 2 K to 300 K in a magnetic field of 1 T for run No. 1. Solid lines show the Curie-Weiss fits. Pressure evolution of (b) the effective moment μeff and (c) the Curie-Weiss temperature ΘCW for run No. 1 (square symbols) and No. 2 (circle symbols). Dashed lines are linear fits.

From the fits to the data between 150 K and 300 K, we find that the Curie constant and the associated paramagnetic effective moment weakly decrease with pressure, whereas the Curie-Weiss temperature increases and even changes sign from negative to positive (Fig. 2), indicating the growth of ferromagnetic interactions. At ambient pressure, the paramagnetic effective moment is around 2.4 μB in agreement with the previous studies11. It decreases with pressure and at 2 GPa reaches 1.8 μB, which is close to 1.73 μB expected for the ({j}_{{rm{eff}}}=frac{1}{2}) state of Rh4+.

At low temperatures, the smooth evolution of the magnetic susceptibility is consistent with the absence of any magnetic transition. The spin freezing reported below 6 K at ambient pressure9,11 can be tracked by the bifurcation of the magnetic susceptibilities measured under field-cooled (FC) and zero-field-cooled (ZFC) conditions in low applied fields. Such measurements become quite challenging under pressure because of the weak signal in low magnetic fields. Nevertheless, it was possible to track the FC/ZFC susceptibilities of Li2RhO3 in the applied field of 0.1 T up to 3.46 GPa (Fig. 3). The spin-glass like behavior of Li2RhO3 remains almost unchanged upon compression. The bifurcation of the FC/ZFC susceptibilities is seen at around 5.0 K at all pressures.

The data are vertically offset for clarity. The solid symbols show the data collected upon field cooling (FC), whereas open symbols are the data collected upon zero-field cooling (ZFC).

Microscopic magnetic model

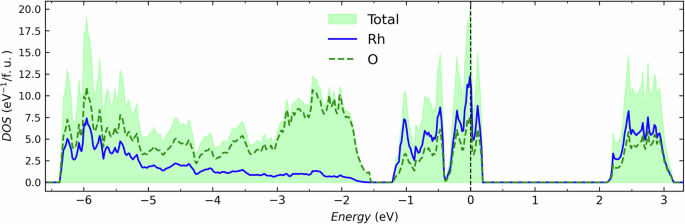

Figure 4 shows the density of states for Li2RhO3 calculated on the full-relativistic (PBE+SO) level. Typically for a transition-metal oxide, the bands near the Fermi level are dominated by the d-states that are split into the t2g and eg manifolds by the octahedral crystal field. The t2g − eg splitting is about 3.0 eV compared to the splitting of 2.0 eV in α-RuBr324 and 2.2 eV in α-RuCl325, in agreement with the higher negative charge of O2−.

The Fermi level is at zero energy.

From the orbital energies obtained via the Wannier fit, we extract a small noncubic crystal-field splitting of only 13 meV, which is well below the spin-orbit coupling constant for Rh4+. However, the t2g states do not show the splitting into ({j}_{{rm{eff}}}=frac{3}{2}) and ({j}_{{rm{eff}}}=frac{1}{2}) bands known from the Ir4+ compounds. There is instead a three-peak structure reminiscent of Na2IrO326, with the peaks at -1.0, -0.7, and 0.0 eV. This splitting into three sub-bands is a fingerprint of the dominant off-diagonal hopping (t2) that takes place between, e.g., the dyz and dxz orbitals and gives rise to the large Kitaev coupling27. Our direct calculation of the exchange tensor confirms this assessment.

We define the exchange tensors in the Kitaev coordinate frame as

with four independent parameters (J, K, Γ, and ({Gamma }^{{prime} })). Technically, the X– and Y– bonds have a lower symmetry with six independent parameters28, but our calculations show that the approximate form given by Eq. (1) is sufficiently accurate for these bonds as well, so it will be used in the following. The X– and Y– bonds are symmetry-equivalent but different from the Z-bonds. This difference is also relatively small at all pressures, as can be seen in the Supplementary Information. Therefore, in the rest of this work we will discuss the couplings averaged over the X-, Y-, and Z-bonds of the honeycomb lattice. We label these averaged couplings as (bar{J}), (bar{K}), (bar{Gamma }), etc.

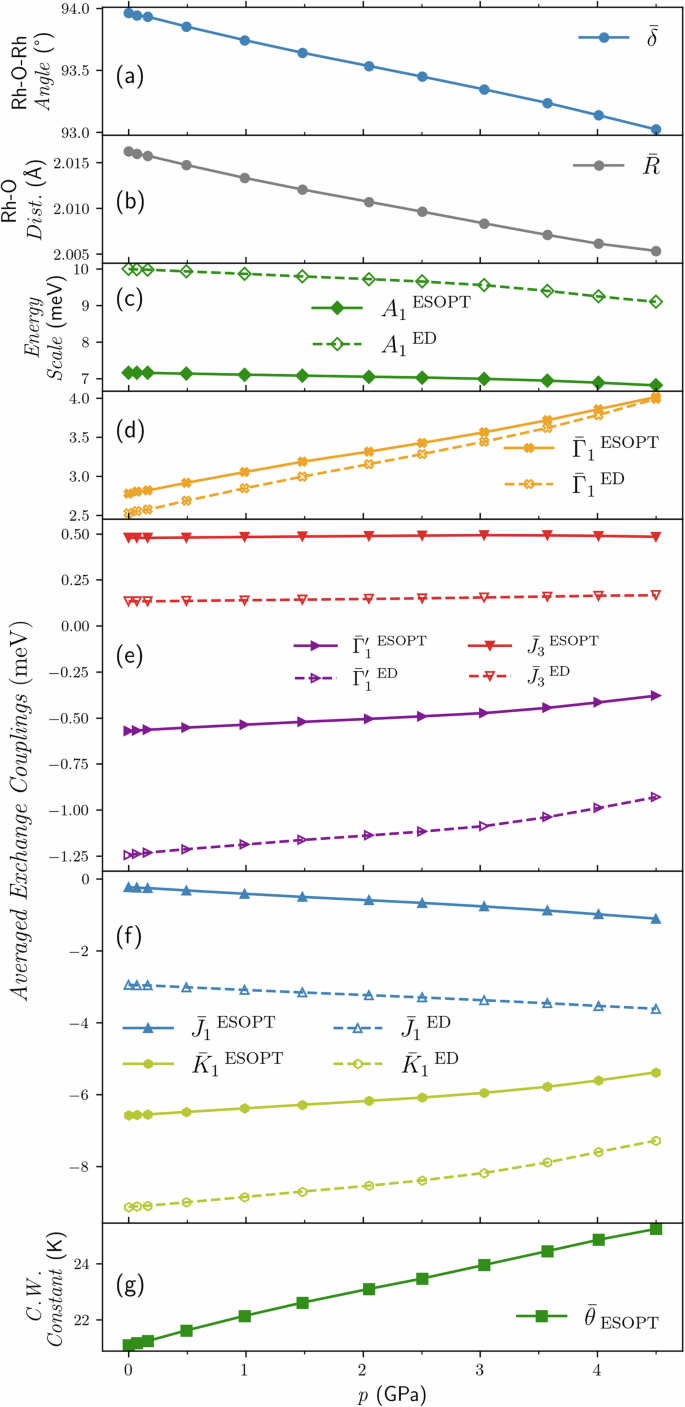

Figure 5 shows such averaged exchange couplings as a function of pressure. Li2RhO3 is dominated by the ferromagnetic nearest-neighbor Kitaev term K1 that decreases in magnitude upon compression. The off-diagonal anisotropy Γ1 increases under pressure, with the ({bar{Gamma }}_{1}/| {bar{K}}_{1}|) ratio changing from 0.34 at 0 GPa to 0.60 at 4.5 GPa. The nearest-neighbor Heisenberg coupling is weakly ferromagnetic and also increases in magnitude upon compression.

a Averaged Rh-O-Rh angle (bar{delta }). b Averaged Rh-O distance, (bar{R}). c Overall energy scale (A={({{bar{J}}_{1}}^{2}+{{bar{K}}_{1}}^{2}+{bar{Gamma }}_{1}^{2}+{bar{Gamma }}_{1}^{{prime} 2})}^{frac{1}{2}}). d Off-diagonal anisotropy ({bar{Gamma }}_{1}). e Off-diagonal anisotropy ({bar{Gamma }}_{1}^{{prime} }) and the third-neighbor coupling (bar{{J}_{3}}). f Nearest-neighbor Kitaev (({bar{K}}_{1})) and Heisenberg (({bar{J}}_{1})) couplings. g Calculated pressure-dependent Curie-Weiss temperature. All lines are guides to the eye only.

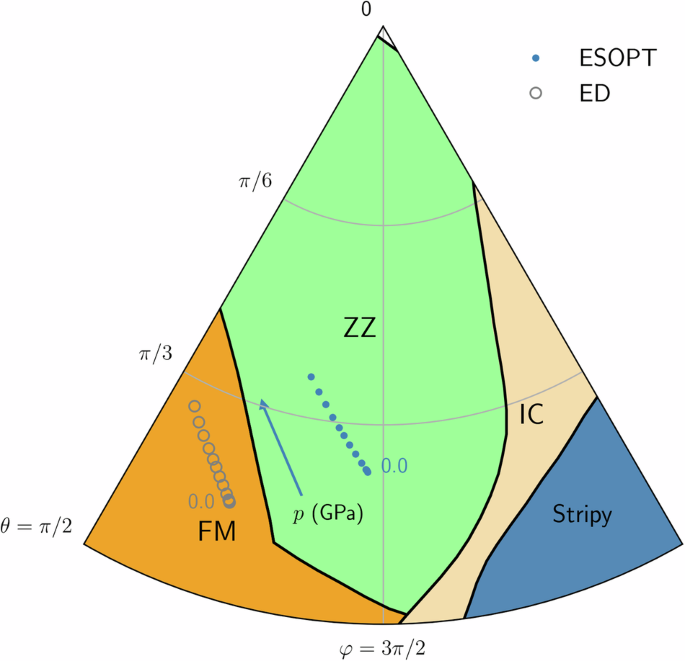

These pressure-induced changes in the nearest-neighbor couplings are well in line with the structural changes upon compression. Indeed, the Rh–O–Rh bond angles systematically decrease, leading to a reduction in the off-diagonal hopping t2 and the weakening of the Kitaev term relative to the other terms of the exchange tensor28. This mechanism appears to be generic for the Kitaev magnets that all show the reduction in the bond angles under hydrostatic pressure and the gradual suppression of the Kitaev term17,22,24. The evolution of Li2RhO3 can also be followed on the phase diagram of the J1 − K1 − Γ1 model (Fig. 6) where pressure systematically shifts the system away from the Kitaev limit located at φ = 3π/2.

The parameterization in polar coordinates corresponds to ({J}_{1}/A=sin theta cos varphi), ({K}_{1}/A=sin theta sin varphi), and ({Gamma }_{1}/A=cos theta) where θ is the radial part, φ is the angular part, and A is the overall energy scale defined in the caption of Fig. 5. The values averaged over the X-, Y-, and Z-bonds are used. Note that J3 is not included. It is expected to stabilize zigzag order (ZZ) at the expense of the ferromagnetic order (FM).

Turning to the smaller terms in the spin Hamiltonian, we note that the off-diagonal anisotropy ({Gamma }^{{prime} }) is below 1 meV at all pressures. Its negative sign should increase the proclivity of Li2RhO3 for zigzag order, as shown in the phase diagram of Fig. 6. However, the main term stabilizing the zigzag order is believed to be the antiferromagnetic third-neighbor coupling J3 that has been estimated at about 1−3 meV in α-RuCl34,29,30,31 and 2−6 meV in Na2IrO328,32,33,34. Surprisingly, the ({bar{J}}_{3}) of Li2RhO3 is quite small, about 0.15 meV according to our cluster many-body calculations. This suppression of ({bar{J}}_{3}) may be a result of the smaller spatial extent of the Rh 4d orbitals compared to the Ir 5d orbitals of the iridates, and of the O 2p orbitals compared to the Cl 3p orbitals of α-RuCl3. Interestingly, ({bar{J}}_{3}) obtained by the cluster many-body calculations is much lower than in the superexchange model. It means that the hoppings to the eg orbitals yield ferromagnetic contributions that are strong enough to compensate for antiferromagnetic contributions from the intra-t2g hoppings.

Discussion

Li2RhO3 remains a forgotten sibling of the much better known Kitaev iridates and Ru3+ halides. Although the first reports of its magnetic properties9,10 even preceded the discovery of α-RuCl3 as a Kitaev candidate, relatively little is known about its microscopic regime. The quantum-chemistry study of Li2RhO3 demonstrated a strong Kitaev coupling but also reported an unusually strong spatial anisotropy with ({J}_{1}^{Z}=-10.2) meV having a different sign than ({J}_{1}^{X}=2.4) meV23.

Our study advocates a more conventional microscopic scenario where spatial anisotropy plays only a minor role, and the couplings on the X/Y– and Z-bonds are qualitatively and quantitatively similar to each other. Moreover, the position of Li2RhO3 on the phase diagram of the extended Kitaev (J1 − K1 − Γ1) model should resemble that of the Ru3+ halides, with the leading ferromagnetic Kitaev term K1 < 0 and the subleading off-diagonal anisotropy Γ1 > 0. The nearest-neighbor Heisenberg exchange, J1 < 0, is relatively small at ambient pressure but becomes increasingly more important upon compression. This trend is corroborated by our magnetization measurements. Indeed, the powder-averaged Curie-Weiss temperature can be calculated as28

and does not depend on ({bar{Gamma }}_{1}). Whereas ({bar{K}}_{1}) decreases in magnitude with pressure, the leading trend is determined by the enhancement of ferromagnetic ({bar{J}}_{1}) that causes the increase in θ upon compression (Fig. 5g). Despite this good qualitative agreement, we note that the slope of the calculated pressure dependence is much lower compared to the experiment. Similar discrepancies have been reported in other Kitaev materials and ascribed to deviations from the simple Curie-Weiss law caused by the temperature dependence of the paramagnetic effective moment35.

Although Li2RhO3 does not approach the Kitaev limit, the combination of ({bar{K}}_{1} < 0) and ({bar{Gamma }}_{1} > 0) as the dominant terms in the spin Hamiltonian is a precondition for the strong frustration that has been comprehensively studied in the context of the K1 − Γ1 model on the honeycomb lattice36. This model connects the limits of the Kitaev spin liquid at large K1 and classical spin liquid at large Γ1, whereas the intermediate region is often described as correlated paramagnet36. With Li2RhO3 lying close to the K1 − Γ1 line on the phase diagram of the ({J}_{1}-{K}_{1}-{Gamma }_{1}-{Gamma }_{1}^{{prime} }) model, at least at ambient pressure, it is not surprising that this material evades long-range magnetic order. Experimentally, we find spin freezing below 5 K that persists at least up to 3.46 GPa. Interestingly, the freezing temperature almost does not change, whereas individual exchange couplings are clearly affected by pressure. This observation suggests that spin freezing is driven by an extrinsic energy scale and may be associated with the structural disorder arising from stacking faults10,16. The high-pressure x-ray diffraction study of Li2RhO3 shows that the concentration of stacking faults is almost unchanged within the pressure range of our study14.

Although stacking faults are unavoidable in almost all Kitaev candidates because of their layered nature12,13,37,38, this structural disorder will usually not preclude magnetic ordering. Na2IrO3, α-RuCl3, and α-RuBr3 all show zigzag magnetic order, which is stabilized by ({Gamma }_{1}^{{prime} }) and J3. Whereas ({Gamma }_{1}^{{prime} }) is a comparably minor term across the whole family of the existing Kitaev materials, Li2RhO3 stands apart from the other Kitaev candidates in that its J3 is unusually small. One can then interpret the absence of magnetic order in Li2RhO3 as the joint effect of the frustration caused by K1 − Γ1 and the weakness of J3. Additionally, the existing Li2RhO3 samples14 show about twice higher concentration of stacking faults compared to Na2IrO332. This increased amount of structural disorder should increase the proclivity for spin freezing.

Finally, we note that our study supports the general trend of tuning Kitaev candidates away from the Kitaev limit by hydrostatic pressure15. One would then expect negative pressure to enhance the Kitaev term, reduce Γ1/∣K1∣, and bring the materials closer to the Kitaev limit. In this context, it is somewhat surprising that Ag3LiRh2O6, the expanded version of the Li2RhO3 structure, not only shows magnetic ordering, but also features the highest Néel temperature among all Kitaev candidates reported to date8. The negative pressure effects in honeycomb rhodates may be nontrivial and clearly deserve a further dedicated investigation.

Methods

Sample synthesis and characterization

Polycrystalline samples of Li2RhO3 used in this work were previously characterized in refs. 11,14. Magnetization under pressure was measured with the same method as in ref. 39 using the gasket with the sample chamber diameter of 0.9 mm that can reach pressures up to 2 GPa. In order to reach higher pressures, the gasket was pre-indented, and pressures up to 3.46 GPa could be reached in run No. 3. A piece of Pb served to determine pressure from the temperature of its superconducting transition. Daphne oil 7373 was used as pressure-transmitting medium.

DFT and cluster many-body calculations

Density-functional band-structure calculations were performed in the FPLO code40 using the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) version of the exchange-correlation potential41. Hopping parameters were obtained by the built-in Wannierization procedure of FPLO42. Previous studies reported only the lattice parameters of Li2RhO3 as a function of pressure14, whereas oxygen positions had a large uncertainty due to limitations of the x-ray powder diffraction data. Therefore, we chose to fix the lattice parameters to their experimental values at each pressure and relaxed the atomic positions using DFT+U calculations in FPLO, performing force optimization until the residual forces were less than 1 × 10⁻³ eV/Å. At ambient pressure, we obtained the Rh–O distances (R1, R2, R3 in Fig. 1a) of 2.0395/1.9713/2.0379 Å, the Rh–Rh distances (Z, XY) of 2.9812/2.9315 Å, and the Rh–O–Rh bond angles (labeled as δ1, δ2) of 93.91/94.01°, which are in a good agreement with the experimental values7 of 2.033(6)/2.001(7)/2.029(3)/Å (Rh–O1/Rh–O1/Rh–O2), 2.950(4)/2.954(5) Å (Rh–Rh), and 94.16/93.29° (Rh–O1–Rh/Rh–O2–Rh). We also note that the experimental structural data for Li2RhO3 feature a weak Li/Rh site mixing7. This site mixing is caused by the interlayer disorder, such as stacking faults, whereas individual honeycomb layers are well-ordered8. Therefore, we used the fully ordered structural model in our calculations.

Magnetic couplings in Li2RhO3 are defined by the general spin Hamiltonian,

where ({{mathbb{J}}}_{ij}) is the exchange tensor for the respective bond, and the summation is over bonds. The ({{mathbb{J}}}_{ij}) components were determined by two complementary approaches. In the superexchange model, the hoppings within the t2g manifold of the scalar-relativistic band structure are used to calculate the exchange couplings as described in ref. 28. Weak crystal-field splittings within the t2g manifold and virtual processes involving the eg states are neglected in this method.

Cluster many-body calculations allow a comprehensive treatment of the microscopic processes that underlie the exchange couplings. In order to calculate exchange couplings, we start by deriving the electronic Hamiltonian in terms of Rh 4d orbitals Wannier basis42. We obtain this Hamiltoninan by performing fully relativistic (PBE+SO) calculations using a k– grid of 12 × 12 × 12 and retaining the translational symmetry of the system. The obtained electronic Hamiltonian is exactly diagonalized on two-site clusters to get the low-energy eigenstates. These eigenstates are then projected to pure spin states by following the des Cloizeaux effective Hamiltonian method43 to obtain the intermediate states which are finally orthonormalized by employing the symmetric (Löwden) approach44. The advantage of the above described procedure is that it preserves all the symmetries and includes the effects of the non-cubic crystal-field splitting and nominally empty eg orbitals that are neglected in the superexchange model.

In both cases, we used the same parameters of U = 2.58 eV and JH = 0.29 eV for the on-site Coulomb repulsion and Hund’s coupling, respectively, as determined for α-RuCl345. The spin-orbit coupling λ = 0.15 eV was used in the superexchange model.

Responses