Preventing ischemic heart disease in women: a systematic review of global directives and policies

Introduction

In this global phenomenon of an aging population, cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide1. More older women are living with the complexities, challenges, and complications of heart disease2. At the same time, there is also a rising trend of younger women being diagnosed earlier with ischemic heart disease (IHD)3. While this is in part due to the key drivers of cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity, this only accounts for part of the problem. Despite being the same disease, the pathophysiology, symptoms, social determinants, and impact, between men and women differ significantly4. Females with heart disease experience more symptoms, more hospitalizations, worse outcomes after discharge, and poorer quality of life5.

Although many of the cardiovascular risk factors are universal, these risk factors impact women differently, resulting in differing pathophysiology, presentation and outcomes between men and women6. As a result, women were often underdiagnosed due to the lack of recognition of these differences and the historical misperception that CVD primarily affected men while women’s health was defined narrowly by sexual and reproductive health issues6,7,8. In addition, women may have other non-traditional risk factors such as pregnancy complications, history of breast cancer, autoimmune and inflammatory disease, and early-onset menopause that can affect their development of IHD9. Women tend to typically exhibit symptoms of IHD roughly a decade later than men and often have unique characteristics10. These can include myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary artery disease (MINOCA), or complications of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFPEF)6. In addition, the effectiveness and side effects of drugs can exhibit sex specific variations. For example, aspirin appears to be more beneficial for men compared to women in primary prevention and reduction of non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI)7,11. Conversely, women are more likely to experience adverse drug reactions from bleeding complications with antiplatelets and anticoagulants to developing myopathy with statins12.

Beyond the biological differences between males and females, how women communicate, perceive risk and engage in health seeking behaviors are often differ from men13,14.There are differing gender, societal, and cultural expectations and roles throughout a women’s life course that influences her health seeking behavior, psychosocial wellbeing, and treatment access. The changing roles of women, higher educational levels, and diverse cultures affects how women respond to health promotion campaign advertisements or social media and other public health policy interventions15. These social determinants of health are inextricably linked to biology and contribute to CVD outcomes16,17. For instance, in many societies, women are traditionally viewed as primary caregivers who prioritize their family’s needs above managing their own health. Increasing numbers of women are also taking on non-traditional roles such as being breadwinners and furthering their careers, which can make it challenging to set aside time to prepare healthy meals, exercise, attend health screenings or medical appointments18.

With advances in the field of women’s heart health, education and awareness, advocacy and policy, the importance of preventing heart disease in women has started to receive more attention in the last two decades, especially in the United States. These efforts have contributed to a significant decline in mortality from heart disease in women19. However, recent trends show a plateauing of this decline19. Multiple studies have shown that there is a lack of awareness about sex-specific symptoms among women, which can result in delayed health seeking behavior20,21,22,23. Physicians were more likely to undermine women’s symptoms and less likely to refer them to a cardiologist for definitive care24. There is also a lack of healthcare services dedicated to managing women’s health issues beyond reproductive and childbearing services25. This consequently leads to inadequate healthcare access, delayed time to receiving definitive diagnostics such as coronary angiogram, suboptimal medical therapy, and higher inpatient and post-discharge mortality from heart attacks amongst women compared to men26,27,28. The stark reality remains that heart disease is the leading cause of death in women, even more than breast and cervical cancer combined28.

Though much progress has been made in women’s health and rights since the 1995 Beijing declaration and platform for action, this work remains incomplete more than twenty-five years later29. Empowering women to make informed decisions for their bodies does not stop at reproductive health, the cardiovascular health of women is equally important and needs to be addressed. Strategies have to take into consideration the life course and unique health determinants of women. However, research findings and recommendations are not necessarily translated to changes in public health practice. Specialist care and public health views are often unsynchronized30. Policies may not be equally implemented among countries or ethnicities. Inequalities exist among women with varying socioeconomic status and race between countries, and even within countries31. There is an urgent need to identify and consolidate current policies in order to identify gaps in the care of women’s heart health. Therefore, this systematic review adopts a life course perspective to comprehensively examine existing global recommendations and policies addressing primary prevention of CHD in women. It also assesses the connection between the clinical recommendations and policy, while identifying gaps in care that can inform advocacy efforts and future policy planning for promoting cardiovascular health across the lifespan of women.

Results

Study context and characteristics

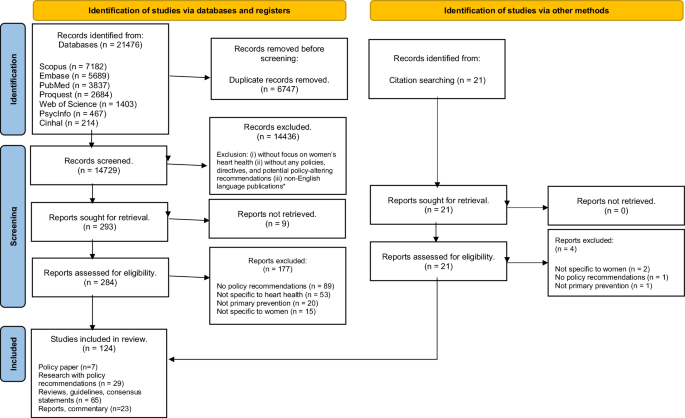

Figure 1 summarizes the data selection and screening process. Of the 21476 records that were produced by searches, we identified 124 eligible studies for synthesis of their results in this review. The list of included studies is available in Supplementary Table 1. The detailed distribution of studies and their recommendations or outcomes across countries and life-course is in Supplementary Tables 2–8. Articles were categorized into young women, pregnancy-related, women in midlife, older women, women of minority groups, and general articles, which aided descriptive analysis and enabled development of key themes relating to women’s heart health.

The PRISMA flow diagram of publications included in the systematic review of global directives and policies for preventing ischemic heart disease in women.

There were only 12.9% (n = 16) articles that directly discussed policy relating to women’s heart health. We classified studies into various subcategories, with most of the articles focusing on women in general, not specific to a particular stage in the life course. During critical appraisal of the publications, 103 were assessed to be of high quality, 21 medium quality, and none of low quality. Studies were categorized as public health intervention typologies of advocate (n = 8), support (n = 82), collaborate (n = 4), and direct action (n = 30). Details of the included studies are found in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 9.

Life course approach

We adopted a life course approach in our analysis. We recognize that women’s heart health is a dynamic process that changes over a woman’s life course (young women [youth and preconception], pregnancy and postpartum, midlife and menopause, and elderly) and across generations. Women’s heart health is influenced by physical, environmental, and psychosocial factors; and across ecological levels (biological, individual, family, community, and national). These findings are highlighted in Table 2. While most publications were able to fit into a specific life course, some publications were less specific to a phase in life, and are presented separately. We also separately presented findings with regards to different ethnicities groups and minorities.

Young women

Young women (<35 years of age) have the lowest awareness of risk factors for CVD and are the least likely to engage in dialog with their physicians about heart disease32. Key risk factors are lifestyle choices33, the effects of reproductive hormones34,35,36 and the increasing use of cigarettes37.

We identified 6 publications dedicated to addressing preventative CVD interventions in young women32,37,38,39,40,41. Although the incidence of IHD is low in this age group, the onset of atherosclerosis can nevertheless occur as early as childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood in patients with a genetic predisposition, or conditions such as obesity, and polycystic ovarian syndrome39. However, more often it is due to lifestyle choices such as sedentary behavior, unhealthy diets, smoking, and even use of oral contraceptives, that set the path for the development of cardiometabolic risk factors33. Regrettably, routine screening for asymptomatic familial conditions such as familial hyperlipidemia or early onset hypertension, is rarely offered to younger women42, which further contributes towards CVD being overlooked among this population. In addition, traditional CVD risk calculators such as the Framingham Risk Score, underestimates the lifetime risk of heart disease in young women with non-traditional risk factors32. This underestimation often results in a false sense of security and a disregard for CVD prevention in young women.

Studies suggest that factors related to reproductive hormones can also affect cardiovascular risk. Emerging risk factors such as early menarche, or abnormal menstrual cycle lengths, is associated with an increased risk in CVD development34,35,36. Thus, menstrual history should not be taken lightly as it is a potentially useful tool to increase awareness about CVD and use for early counseling of future CV risk. Policy efforts should target toward increasing awareness of heart disease and risk factors for young women.

Among this age group, there is also a worrying trend of increased cigarette use especially in Southeast Asia and the United States due to social and marketing influences32,43. For many years, popular culture has implied that smoking aids in weight control, and this has become one of the most frequently cited reasons for smoking among younger women32,43. Smoking and taking oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), also results in a mild increase (approximately 5%) in blood pressure in most women, which results in a fivefold increase in risk of heart attacks37. With the global prevalence of smoking among women expected to hit 20% by 202544, policy efforts should focus on ways to reduce smoking rates among young women. For instance, calls have been made in the United States for tobacco laws to make packaging plain and simple, as plain packaging has been shown to discourage tobacco use45.

While there are clear recommendations and calls to improve early detection of risk factors of CVD, advocacy and lobbying efforts in this subgroup primarily target the tobacco industry. No policies or recommendations were found addressing the use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) or other types of nicotine products among women. Current literature findings with regards to the long-term health effects of routine e-cigarette use are unclear46, with some studies reporting no significant association between e-cigarette use and CVD47,48 while another study suggests that daily users of e-cigarettes have an increased risk of myocardial infarction49. Longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the association between e-cigarette use and CVD to inform the development of policies targeting this growing group of e-cigarette users. Overall, specific policy recommendations for young women are still lacking at the present.

Pregnancy and postpartum

Key risk factors for women in this life-stage include gestational complications such as diabetes and hypertension50 and corresponding lack of awareness of the need for screening during pregnancy. However, current policies and directives for pregnant women primarily focus on the child’s health and wellbeing above the mother’s, often neglecting the significant impact that pregnancy can have on the woman’s health.

In our analysis, we found 16 publications that addressed pregnancy-related disorders in the context of preventing maternal heart disease37,38,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64. Based on the public health typology model, most of these publications were classified as providing guidelines or reference materials to support pregnant women.

Women with a history of maternal pregnancy complications such as gestational hypertension and gestational diabetes have a higher risk of developing CVD65. This is reflected in our search, where there is much focus on hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (n = 6, 37.5%) and gestational diabetes (n = 8, 50%), which affects up to 10% of pregnancies respectively50. These conditions are included in both the American Heart Association (AHA) and ESC guidelines as major risk factors for CVD66. Other pregnancy complications, such as fetal growth restriction, preterm delivery, and pregnancy loss are also associated with an increased risk for CVD. When one of these problems exists, the risk of CVD events nearly doubles, and 20–30% of pregnant women may unknowingly carry a factor that predicts their future CVD risk66. Even women who are unable to breastfeed or experience disrupted lactation may face a greater risk for heart disease and other metabolic disorders later in life54.

Acute coronary syndromes during pregnancy can occur due to atherosclerosis as well as spontaneous coronary artery dissection and coronary thrombosis67. This is growing to be a concerning issue as the average maternal age rises and maternal mortality from CHD rises. To prevent maternal and fetal complications, better efforts are needed to raise healthcare professionals’ awareness of CVD risk in pregnancy so as to better facilitate opportune screening, education, and risk factor optimization protocols for those planning to conceive and during pregnancy51. Risk stratification tools such as World Health Organisation (WHO) classification of maternal cardiovascular risk, Cardiac Disease in Pregnancy (CARPREG), and Zwangerschap bij Aangeboren HARtAfwijkingen (ZAHARA) risk scores can be useful for preconception counseling and triaging care during pregnancy68,69,70. Women at higher risk should be managed by a cardiologist throughout their pregnancy and should have close reassessment of their blood pressure and blood glucose levels within 6 weeks postpartum, when the risk of maternal mortality is the highest52. It is recommended that if levels have not normalized, they should be managed by a primary care physician or cardiologist where appropriate. In addition to the immediate postpartum period, it is also essential to increase physicians and women’s awareness of the association between prior adverse pregnancy outcomes and future CVD risk57.

Despite the alarming evidence that CHD is responsible for more than 20% of maternal deaths68,71, policy recommendations for heart disease in pregnant women are lacking. While there are some policy driven initiatives, such as the “Starting well” to improve maternal and child nutrition in the United Kingdom72, there is a need for more comprehensive policies that prioritize the mother’s health and address outcomes related to maternal cardiovascular risk factors. In 2000, the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, outlined a policy development to assist researchers, health practitioners, and policymakers in creating a community where women, regardless of socioeconomic status, would receive effective medical care for prevention of heart disease and stroke73. Since then, tailored educational programs with dedicated facilitators have been developed, such as the IMPROVE postpartum program launched by the Heart Institute at the University of Ottawa and the Canadian Women’s Heart Health Center to support women who have experienced preeclampsia, eclampsia, or gestational hypertension74. Within the United States, the AHA has recently published guidelines on CVD prevention in pregnant women urging health systems to provide aggressive measures for prevention of heart disease in women experiencing pregnancy complications54. In their findings, there were significant disparities in adverse pregnancy outcomes, with women of color at a higher risk than white women, the AHA has called for healthcare providers and policymakers to prioritize CVD prevention in women, particularly those at higher risk due to adverse pregnancy outcomes54.

Policy development outside of UK and Canada for cardiovascular health in pregnant women are lacking.

Midlife and menopause

Key risk factors during this transitional stage of women’s lives include bio-psycho-social changes such as hormonal changes, work-related issues and lifestyle choices75.

Midlife, a period of transition in women’s lives, is defined as the period of the lifespan between younger and older adulthood. Women in this age group typically experience multiple social, psychological and biological challenges such as family issues, health concerns, work-related issues, financial worries, and menopausal transition75.

Menopause, the midlife transition resulting from depleting ovarian reserves and lower estrogen levels, brings with it a host of changes76. The cessation of periods and the onset of hot flashes are just the tip of the iceberg. The hormonal changes associated with this phase can lead to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, including higher blood pressure and cholesterol levels76. We found 11 publications directly addressing prevention of heart disease during menopause37,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86.

Obesity and metabolic syndrome are common problems that women face after menopause. The onset of menopause is associated with a shift in body fat composition with increase in central obesity and decreased energy expenditure87. Obesity, which is more prevalent in women than men, is associated with significant cardiovascular risk88. The risk of developing acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in obese women is 4 times higher, and the risk of developing ischemic stroke is 2.65 times higher, than in women with a normal reference BMI89. In particular, women who experience premature menopause are also more likely to develop CVD86. Studies have also suggested that when compared to men, women are more vulnerable to worst CV outcomes when they develop metabolic syndrome or when their BMI rises81,83,90. Lifestyle factors affecting obesity such as increased sedentary time and an unhealthy dietary pattern lead to poorer outcomes for women in the context of CVD development. Even minor weight gain (between 4-10 kg) is associated with a 27% increased risk of CHD compared to women who maintain their weight91. Screening for these CV risk factors during this transition to menopause or when women present with hot flashes can aid in early detection and management of CHD before it becomes established.

In developed countries like the United States, Chronic IHD, heart failure, and AMI are three of the leading causes of death for women over 5092. Furthermore, more than 10% of women over age 50 smoke, this contributes to an increase in the incidence of earlier onset AMI in women93. Schwarz et al. advocates that preventive strategies to improve knowledge and promote behavioral change such as healthy diets, physical activity, tobacco abstinence, and reduced alcohol consumption are still relevant. Tobacco policies, which were previously addressed among younger women, continue to have an impact. While such policies and measures aim to reduce smoking initiation, the emphasis for women in this stage of life should instead be focused on smoking cessation93.

Despite cumulative evidence indicating reduction in cardiovascular events with hormone replacement therapy (HRT), when initiated in women less than 60 years or within 10 years of menopause, HRT is not recommended as part of armamentarium for CVD prevention in women77,83,94. The “timing hypothesis” posits that the early beneficial effects of estrogen are seen only on healthy vascular endothelium but reverse adverse effects are seen on atherosclerotic plaques, and RCTs show that HRT does not reduce the risk of CVD in late postmenopausal women77,83,94. International guideline recommendations for HRT are primarily for helping women cope with severe hot flashes related to menopause but not as a means for preventing coronary heart disease. It is also not recommended for women with high CVD risk78,80,85,95. Lifestyle changes and pharmacological interventions should however be introduced in perimenopausal women to minimize cardiovascular risk. The management of the perimenopausal woman is not the exclusive responsibility of the gynecologist. An interdisciplinary approach should be adopted with the gynecologist not just evaluating vasomotor and urogenital symptoms, but also assessing the patient for cardiovascular risk80. Individualized risk assessment is required for assessing potential harms versus benefits of HRT for management of vasomotor symptoms in the context of CVD risk, and women should be given the opportunity to consult their healthcare providers about the safety and types of HRT, or discuss other alternative approaches (e.g., lifestyle modifications or lipid management) to lower their risk factors for heart disease while managing their menopausal symptoms83.

One of the largest focused efforts targeting this age group in the United States is the Well-Integrated Screening and Evaluation for Women Across the Nation (WISEWOMAN) program which targets women aged 40–64 years and are of lower socioeconomic status96. It is a three-stage program aimed at reducing CVD96. The first stage (1995–1998) was devoted to research to determine the efficacy of interventions in comparison to standard treatment. The second stage (1999–2007) focused on funding and piloting these solutions in local contexts. The third stage (2008-present) is concerned with implementation. The program offers free CVD examinations and counseling to women who qualify. Women who participate in this evidence-based lifestyle program receive one-on-one health coaching or are connected to other community resources. The services offered by each WISEWOMAN program vary but they are all designed to encourage long-term, heart-healthy lifestyle changes97,98. The program guidelines for lifestyle interventions provide structure while implementation strategies are flexible. The study found that high-performing sites were sensitive to the differences and needs of women in their community and adapted accordingly in their service delivery. They reached out to women through a variety of providers and community organizations, and improved efficacy by offering regular staff training, teaching behavior change theory, and providing adequate resources. Adoption of techniques required teamwork and adaptability, and success in implementation required training, partnerships, tracking systems, and constant reminders99.

Other efforts in the United States targeting heart diseases among women in mid-life is The Heart Truth®, a federally sponsored national health education program, launched by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in September 2002100. While the initial target was to raise awareness in heart diseases among women in mid-life, this has since expanded to include younger women with initiatives such as using the Red Dress® as a symbol for women’s heart disease, and organizing the Red Dress® collection fashion show and concert which coincides with New York fashion week. The effective use of the Red Dress® branding and social marketing has fueled the campaign’s three-part implementation strategy of partnership development, media relations, and community action through its broad appeal to women. Five years after the launch of The Heart Truth®, it was reported that women’s knowledge of heart disease had increased, and women were more aware of what can be done to reduce their chances of developing CVD. The Heart Truth® was implemented successfully because it is a non-generic, targeted and tailored program that captures stakeholder’s attention and meets their needs.

Elderly women

Key risk factors amongst elderly women include diagnostic and treatment disparities amongst genders101, lack of health literacy and psychosocial factors such as social isolation102.

Post-menopause, the prevalence of heart disease increases dramatically in women. In the AHA 2019 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistical Update, prevalence of CVD is 77.2% in males and 78.2% in females between the ages of 60 and 79 years. The statistics were even more startling for older adults aged 80 and above, at 89.3% in males and 91.8% in females28. With an aging population, a longer average life expectancy than men, and greater consequence of coronary artery disease from diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking, older women are at a higher risk of developing and accumulating functional disability and consequences of CVD such as HFPEF and coronary heart disease103. There are however few policies and directives looking at prevention of heart disease for elderly women91,102,103,104. Whether this is a reflection that preventive efforts are best undertaken earlier in life or they are understudied is uncertain.

Even though older women have a higher risk of developing CVD than men, disparities are still present in interventions between men and women of this age group. Elderly women utilize less acute diagnostic and therapeutic interventions, revascularization procedures, and were frequently on a less aggressive post-infarction risk reduction strategy101. Interventional studies to reduce risk of adverse events, rehabilitation, and treatment of heart disease include only few, if any, older women103. While there are sex differences in pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics of many preventive medications such as anti-hypertensives which commonly have more adverse events in women, currently the same therapeutic recommendations are used to treat both older men and women81,105.

Aside from age and sex tailored treatment recommendations, addressing lifestyle and psychosocial factors are also equally important. Although psychosocial factors are significant risk factors regardless of gender, women experience different sources of psychological distress than men. A cohort study of older women aged 65 and above, in the United States, discovered that social isolation and loneliness are risk factors for CVD102. Social isolation and feelings of loneliness have been found to impact women’s cardiovascular health by increasing systolic blood pressure leading to atherosclerosis development102. Older women who are socially isolated or lonely have an increased risk of CVD by 11.0% and 16.0%, respectively102. In a study looking at the association of physical activity and CV health determinants in aging women, Sawatzky et al. advocates that improving cardiovascular health and physical activity in aging women needs to be developed in the context of a health promotion model91. Sawatzky et al advocates increasing individual self-efficacy, providing a supportive community, and re-focusing policies to create healthier living populations rather than economic growth and focusing on health promotion over healthcare91.

However, more research is required to understand cardiovascular health promotion and management in aging women.

Others distinct ethnic groups and minorities

We found 29 publications addressing prevention of heart disease among various ethnic groups, minority, and socially disadvantaged groups in both developed and developing countries38,72,97,98,99,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129. Compared to men, women were overrepresented in the lower socioeconomic and minority groups. Cardiovascular health and quality of life among women were disproportionately affected by gaps in resources such as, education, finance, nutrition, and access to healthcare130.

In the United Kingdom, women from lower socioeconomic backgrounds who received welfare benefits were more likely to frequently eat processed foods and have higher table sugar intake instead of nutrient dense foods such as cereal, fish, fresh fruits and vegetables. Results from community programs targeting diet as a CVD risk factor, were often lacking and not sufficiently powered to show outcomes in lower SES women72. In the United States, participants who were Hispanic or non-Hispanic Black were found to be more likely to be obese than non-Hispanic Whites107. Among a multi-ethnic Southeast Asian population, females of Malay ethnicity had a higher risk of developing premature CHD, this was related to the higher prevalence of uncontrolled diabetes contributed by regular consumption of sweetened condensed milk in beverages126. Malay women were also less likely to be highly active due to Muslim religious and cultural beliefs which regards high activity levels in women as inappropriate126. Malay women were also more likely to be affected by passive smoking as Malay men smoked more than any other ethnicities, with this trend being more prevalent in lower-income communities126. In China, the average BMI of Muslim Uyghur women was 24.1 kg/m2, with the prevalence of obesity and overweight being 15.1 and 28.9%, respectively. A study by Cong et al. proposed a pragmatic cost-effective two-step strategy to target this population, first to screen for obesity and then to screen persons with obesity for diabetes and CVD109.

In ethnic minorities, unique ethnic, cultural, lifestyle and genetic predisposition for CVD will need to be considered particularly when intertwined with environmental factors such as limited access to healthcare, strained resources, chronic stress, and availability of cheaper processed high caloric foods, resulting in increased prevalence of cardiovascular risk factor and heart disease.

Aside from low SES, a lack of CVD knowledge remains a major concern in minority groups. A longitudinal study in the United States found that responses to the leading cause of death among US women differed by race and/or ethnicity107. Non-Hispanic Whites had a correct response rate of 87.6%, while Non-Hispanic Blacks had a rate of 64%. Asian/Pacific Islanders, on the other hand, had a correct rate of 55.9%, while Hispanics had a rate of only 28.3%. Only 21.2% participants with ≤12 years of education correctly identified the leading cause of death in CVD as compared to participants with >12 years of education107. Similarly, a cross-sectional survey in Korea also reported a need for nationally driven cholesterol education programs for all middle-aged women in Korea, particularly for women in rural areas who were less knowledgeable yet more vulnerable to CVD122. This further supports the importance of ensuring that women in the minority groups have the necessary knowledge of CVD risk factors in order to prevent CVD development. It is also critical to educate young women about CVD risk factors so that CVD prevention can begin early, in order to prevent the onset of CVD later in life. As this subgroup of women are more likely to seek consultation for reproductive issues during this phase in life, family planning programs and obstetricians should also broaden their scope of practice and upskill to include preventive care for chronic disease97,108.

Besides targeting chronic CVD risk factors, other conditions that are prevalent among young women, such as depression, alcohol and substance misuse and abuse, and domestic violence, should not be overlooked. In the Women’s Health Initiative study, minority women were more likely than white women to have depression106. Approximately 15% of white females were diagnosed with depression, compared to 19% of black women, 25.8% of American Indian women, and 26.9% of Hispanic women. Even after controlling for traditional risk factors, the risk of CV death increased by nearly 60% in those with depression106. In particular, lone mothers, compared to partnered mothers, were more likely to suffer from depression, have poorer living conditions, and were 3.3 times more likely to have a myocardial infarction, stroke, or congestive heart failure113,127. The wide range of socioeconomic factors contributing to single mothers’ risk for CVD are not adequately addressed by standard health behavioral models for risk reduction as they have specific financial and social barriers and inequalities which affect their capacity for living a heart-healthy life. Public health and policy research need to encompass policy analysis for influences on the life circumstances of single mothers for reduction of CVD.

In order for heart health strategies to be successful, a multi-level approach with cultural and community specific nuances have to be taken into consideration. Religious based initiatives, community and culturally specific campaigns or programs, collaborations within the public health sector with community institutions, and the government sector are required to be effective in preventing and raising awareness of CVD risk factors in the minority community98,106,108,112,118.

General strategies across the lifespan

We found two dedicated guidelines which directly addressed prevention of heart disease in women in general66,131, and five other dedicated sections in hypertension and CVD prevention guidelines132,133,134,135,136. Preventive measures can be stratified according to a women’s risk for CVD: high, at risk, or optimal state131,137,138. Overall, recommendations are not substantially different from men for non-pharmacological interventions. The only substantial differences are hypertension management in pregnancy, and two class III recommendations whereby it is not recommended that women under the age of 65 years use aspirin routinely for primary prevention, and neither should HRT be used for primary and secondary prevention137,139.

Our analysis also found multiple review articles which summarized the guidelines and latest evidence in managing heart disease in women7,54,137,138,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148. The review articles collectively concluded that there is much room for improvement with regards to knowledge and research in prevention of heart disease in women had much room for improvement149. There is an emphasis on the need to increase knowledge of CVD burden among women, and to recognize difference in heart disease symptoms between men and women18,80. Even within developed countries such as the USA, approximately a third of adults had only basic or less than basic health literacy, with 12% of women having less than basic health literacy. Health literacy is necessary to ensure that women are equipped to participate in cardiovascular disease self-care, including treatment adherence and behavioral modifications to reduce cardiovascular disease risk150.There was also a need to increase physician recognition of women’s risk of heart disease which must start early in a woman’s life, especially since there is an increasing trend of cardiovascular mortality in younger women145,150. To address this issue, global healthcare systems need to change how women’s preventive care is practiced, with visits for family planning, reproductive medicine, breast and cervical cancer screening providing opportunities for heart disease prevention151,152,153.

Several of these articles concluded that in order to increase awareness and understanding of sex differences, women must be represented more within cardiovascular research, and a gender-based approach must be taken to unravel whether sex-specific therapies exist7,154,155. For instance, in HFPEF and Takotsubo syndrome, which disproportionately affects women and has few proven therapies, identification and implementation of effective preventive strategies is urgent143. Beyond examining the pathology and biology, there is also a need to look at socially constructed expectations that differ between men and women. Multifactorial and psychosocial interventions have been studied for addressing cardiovascular health, but few specifically target women. Further qualitative research is needed to address women’s needs and to scrutinize patterns of behavior change and sustainability of such interventions. Evaluation of tailored programs that consider a woman’s life course, stage of behavior change, and subgroups such as those of low SES are crucial. Additionally, research aimed at evaluating policy and environmental interventions is integral150,156. Women also must play an increasingly active role as investigators in cardiovascular research156,157.

With regards to policy development and implementation, decisionmakers need to be provided with up-to-date information about the relationship between women and CVD to make informed and effective policies18,158. At a global level, in a recent commissioned Lancet article looking at reducing CVD burden in women by 2030, they emphasised the need to prioritise both funding in global health organisations for cardiovascular disease health programs in women from socioeconomically deprived regions and scaling up healthy heart programs in highly populated and progressively industrialised regions150. At a national level, comprehensive public policy agendas are needed. This encompasses increasing funding for epidemiological, clinical, and health services research on heart disease health promotion and prevention, implementation of proven preventive strategies for women in public health programs, ensuring accessibility and reducing barriers towards women seeking interventions, and constant evaluation to improve in the quality of care154,159. Examples of such initiatives include the WISEWOMAN projects targeting disadvantaged women by CDC97. This program is covered by the Heart Disease, Education, Analysis, Research, and Treatment for Women Act, which was passed by the American House of Representatives in November 2011 to ensure that women in the United States have adequate access to health-care services, regardless of their socioeconomic background157. Similarly, the Women and Heart Disease Program in New South Wales, Australia focuses on increasing community awareness, community and professionals’ engagement, and research. Some of the implementation strategies include ensuring that heart disease messaging are relevant to women, increasing accessibility to evidence based information, constant engagement with women living with or at risk of heart disease, particularly sub groups at higher risk and finally, via strengthening ties with researchers and physicians who can make a difference in women’s heart health throughout their lives160.

In several South East Asian (SEA) countries (Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines, Indonesia, and Singapore) there are government units responsible for managing initiatives that encompass improved surveillance of risk factors, promotion of healthy lifestyles, and improved delivery of health services. These programs involve multiple sectors, such as the food and tobacco industries, health services, social welfare and schools. In Singapore, a white paper on a culturally centered framework for women’s heart health was released in 2013, which underscored the importance of addressing heart health problems as being situated within the larger socially driven structures161. Unfortunately, in SEA, barriers still exist in the successful implementation of CVD programs in women, and women specific initiatives remain lacking43. The development of a policy document that would provide clear direction for the improvement of women’s heart health is a fundamental step to ensuring provider and population awareness of women’s heart health issues, and the development of a national strategy for women’s heart health162

Within the community, programs and campaigns such as The AHA’s Go Red for Women have encouraged women to improve their heart health, “know their numbers”, and start taking action to reduce risk of heart disease163. This has resulted in more than 70% of women who have participated in the event to go for heart health related screening163. The mass media outreach for Go Red for Women, similar to breast cancer awareness month, has also reached countries in SEA with various regional and national heart associations organizing programs and activities to promote healthy heart among women. For example, since 2005, the Singapore Heart Foundation has also launched their own Go Red for Women campaign164. However, in most SEA countries, these initiatives are still in their infancy and have not, as yet, made an impact on these parameters43. In UK, The British Heart Foundation has also launched an annual “Bag it, Beat it” campaign to raise vital funds for BHF research in heart conditions157. In Canada, the Heart and stroke foundation released a 2018 heart report evaluating the situation in Canada and has listed steps in their program which encompass investing in research for and about women, partnering system leaders healthcare providers, and women with lived experiences, facilitating community support, improving education and awareness, mobilizing inspirational women and promoting self-advocacy, and closing gaps in care within indigenous and ethnic women’s health165. Such efforts involving complex interventions are difficult to evaluate, and their success is even harder to quantify. A discourse analysis of the Canadian heart truth campaign revealed that the campaign’s emphasis on prevention as an individual choice failed to address the material, economic, and social circumstances of women’s lives, which may exacerbate these difficulties. A significant number of women were unknowingly excluded from the campaign as the campaign was framed prevention as an individual choice while ignoring the gender division of socio-cultural realities, economics, childcare, and household work166. Many social determinants of health were left unexplored in this campaign portrayal166.

Regardless of the design of the programs, strategies must be comprehensive yet measurable. Programs should meet the healthcare needs of women and this can be supported by counseling and behavioral change, provision of adequate subsidies or reimbursements, and including partnerships with multiple stakeholders154.

Discussion

Our study involved a comprehensive analysis of the primary prevention strategies for heart disease in women over the last twenty years by adopting a life course perspective. We also evaluated the correlation between clinical recommendations and public health policies, employing the public health typology model. Undoubtedly, notable advancements have been achieved in the last decade towards the prevention of heart disease in women. However, heart disease continues to be the primary cause of morbidity and mortality throughout a woman’s lifetime. Furthermore, gender-based discrepancies in healthcare and outcomes persist, particularly during specific life stages and for specific subcategories of women.

We found that only 16 articles were identified as having focused on primary prevention of heart disease in women with a policy-related perspective. Guidelines, consensus statements, viewpoints, and primary data-related articles made up the remaining articles. The majority of the publications were directed at women in the western hemisphere. Few were directed towards women in Asia. Most of the recommendations were indirectly focused on women with only a limited number of policy papers having direct impact on them. Among these indirect actions, a significant number were primarily supporting type of interventions with advocacy and collaboration being secondary (Supplementary Table 9). It is also noteworthy that the vast majority of policies addressing CVD in women are mainly based in the United States (n = 8, 50.0%), with few policies based in Canada (n = 2, 12.5%), the United Kingdom (n = 1, 6.2%), Australia (n = 1, 6.2%) and Southeast Asia (n = 1, 6.2%). There is a gap in translating recommendations into tangible action despite the fact that there are scores of evidence supporting the need to improve primary prevention of heart disease in women. This highlights the need for intensifying international efforts to address CVD in women, especially in regions with limited policies. There is a need to transition from passive indirect approaches to direct actions that bridge the gap between evidence-based recommendations and practical implementation to reduce heart disease in women worldwide.

Through the adoption of a life course perspective, our analysis revealed that a significant proportion of the papers focused on women across all age groups in a collective manner. There were articles devoted for prevention of heart disease around pregnancy, midlife, and among minority or women in disadvantaged situations, but articles addressing younger women and the elderly were scarce. Although it is understandable that there are few articles for prevention of heart disease, owing to the fact that preventive measures should have been initiated before the onset of old age, it is surprising that programs and policies for younger women are still lacking. In a recent study conducted in the United States, a mere 10% of adolescent and young adult females correctly identified heart disease as the leading cause of death in women167. Despite a lower short-term risk of CVD among younger women, the accumulation of risk factors can result in a high lifetime risk of CVD32. Tailoring information to the understanding of young women, delivering it through commonly used apps and media, and providing bite-sized programs and interventions that fit with their working schedules and other life priorities may increase their willingness to modify their lifestyles to prevent the development of CVD168. Similarly, intervention programs should be tailored to different stages of life in order to effectively promote CV health and heart disease. Youth awareness is crucial in reducing the global CVD burden as it not only empowers young women to adopt healthy behaviors early on, but also fosters healthy habits during adolescence, which is more likely to translate into lifelong behaviors that can have long-lasting impacts on their cardiovascular health. This has the potential to minimize the prevalence of risk factors in adulthood, such as obesity, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol, resulting in a lower total burden of CVD in future generations169. Beyond that, youth not only benefit from awareness initiatives but also become agents of change within their families and communities creating an intergenerational impact. Young women are able to extend the reach and impact of CVD prevention efforts through sharing their knowledge and promoting healthy habits among their peers, parents, and older family members. This intergenerational effect has the potential to create a ripple effect, reducing the burden of CVD on a larger scale.

Despite more than two decades of policies and recommendations, implementation is still lacking. While some of the policies and recommendations are universal, there is a lack in cultural and local practice. The programs and campaigns should be tailored for different cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Cultural adaptation is essential to increase women’s engagement with the programs, ensuring the programs’ effectiveness, relevance, and reach108,116,118,120,121,125. For instance, the Southcentral Foundation WISEWOMAN project demonstrated this merit by focusing not only on women who smoke, but also on women who chew tobacco, simply because Native Alaskan women are more likely than women from other cultures to chew tobacco98. This process of cultural adaptation encompasses more than mere translation of interventions into another language. It requires a comprehensive comprehension of the distinct practices of diverse cultures and the incorporation and amalgamation of interventions into local practices to facilitate acceptance of interventions by local women.

Apart from raising awareness, revising the current practice of primary prevention of heart disease in women and incorporating opportunities for prevention during pregnancy and menopause is another vital component to improving women’s CV health. Seamlessly integrating CVD screening as an integral part of reproductive care, akin to breast cancer screening, is crucial for a comprehensive approach to women’s health. In this manner, healthcare providers can proactively identify early risk factors, facilitate prevention and intervention strategies, and embrace a holistic perspective on women’s well-being. The development of women-centered prevention programs that take into account women’s different stages of life, such as pregnancy and menopause transition provide an opportunity to identify women who are at an elevated risk of developing heart disease in the future. For example, early identification and treatment of pregnancy-related risk factors such as gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, and preterm birth may enhance both the mother’s and child’s long-term CV health38,55,57,59,63,108,136, whereas targeted prevention strategies such as focusing on the management of menopausal symptoms, optimization of hormone therapy if indicated, and addressing or educating about risk factors such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, and weight management will be beneficial to women undergoing menopause transition. An all-inclusive strategy not only empowers patients, but also fosters proactive health management, resulting in improved CV outcomes. By considering the inherent link between reproductive and CV health, healthcare providers can address multiple health dimensions and promote overall well-being among women.

Our systematic review uncovered notable regional disparities in the focus given to women’s heart health. High-income countries generally had more comprehensive policies and guidelines in place, with a greater emphasis on prevention, early detection, and treatment of IHD in women. However, low- and middle-income countries showed limited focus on this issue. This is consistent with WHO’s report, which highlighted that low and middle-income countries account for three-quarters of global deaths and 82% of total disability adjusted life years lost due to CHD169. This further highlights the need for greater awareness and tailored interventions in resource-limited settings to address the growing burden of heart disease, especially among women living in low and middle-income countries. One crucial aspect is ensuring access to affordable healthcare services for subgroups, which requires addressing financial barriers. This can be accomplished through various means, such as expanding health insurance coverage, providing subsidies, or implementing sliding fee scales based on income170,171. In addition, improving access to transportation, reducing wait times, and extending clinic hours can significantly enhance the accessibility of services for subgroups facing logistical challenges. Patient navigation services can be implemented to better aid subgroups in navigating the healthcare system172,173. Patient navigators can help individuals overcome barriers, schedule appointments, provide guidance on available resources, and offer emotional support. These programs can be particularly effective for subgroups facing language barriers, limited health literacy, or unfamiliarity with the healthcare system. Reducing barriers to care requires a multi-faceted approach that addresses cultural, socioeconomic, and systemic factors, but it requires women to first have access to the healthcare system. More in depth analysis regarding the barriers towards women in these populations are required.

While some public health initiatives have been launched to support women’s cardiac health, women continue to be underrepresented in CVD-related research studies and are only limited gender-specific studies conducted to study the prevention and treatment of CVD in women. This hinders our understanding of the prevention and treatment of CVD in women. Besides the biological factors that contribute to CVD in women, we found that psychosocial factors are also important risk factors but are often neglected. Furthermore, women are increasingly taking on more roles such as balancing their careers in addition to caring for their families. These additional stressors on top of caregiving may deteriorate their psychological wellbeing and time for self-care. The environmental and social determinants, as well as life course experiences, underscore the importance of gender approach. To address this issue, it is essential to prioritize and promote the inclusion of women in CVD research studies. As emphasized by Hayes et al., gender analysis and data transparency in federally funded CVD research can significantly address the underrepresentation of women in studies154. It is essential to mandate that all epidemiological, clinical, and health services research funded by federal agencies includes gender analysis. This requirement ensures that researchers analyze and report their findings by gender, identifying and addressing disparities in CVD risk factors, outcomes, and treatment responses between men and women. In addition to gender analysis, making gender-stratified data available to the research community is crucial. This can be achieved by establishing mechanisms for researchers to access and utilize disaggregated data on a sub-group level. Creating a public website or data platform where researchers can contribute and access gender-stratified data can facilitate collaboration and knowledge sharing across institutions and disciplines, enabling further analysis and the development of more targeted interventions. Ultimately, these efforts will contribute to improved healthcare outcomes, personalized interventions, and better CV health outcomes for women.

While there was a previous review by Kouvari et al., on policies and practices relating to cardiovascular prevention in women157, its focus was a narrative description of policies only in the United States, Canada, or the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), without a report on clinical trials, opinion pieces, or other guidelines which had recommendations relating to coronary heart disease (CHD) in women. In contrast, this systematic review extensively reviews existing global recommendations and policies addressing primary prevention of CHD in women and has assessed the connection between the clinical recommendations and policy. In addition, we identified the gaps in care for women’s cardiovascular health, which informs advocacy and future policy planning for women’s cardiovascular health. Nonetheless, our review has several limitations. While we aimed to look at global directives and policies for the prevention of ischemic heart disease in women, the success of implementation and outcomes remain uncertain. Due to the language barrier, we only included studies published predominantly in English, resulting in the omission of 11 potential articles (Fig. 1), which may have possibly overestimated the effectiveness or significance of global directives and policies for the prevention of CHD in women. It is important to highlight that the majority of the publications in our review are based on developed countries and only two publications targeting developing countries are included. Although differences are apparent between developing and developed countries, there are still a range of commonalities that allow for a global approach to improving women’s CV health174. Future reviews should strive to develop an inclusive search strategy that encompasses multiple databases, including those with non-English publications.

Nonetheless, our review can be used as a guide for developing CVD programs targeted specifically at women, as well as recommendations for future policy papers. In our opinion, a multifaceted approach considering physiological, social, economic, and political determinants is critical to improve the cardiovascular health outcomes of women. Furthermore, given that the odds of surviving CVD are higher when the disease is detected, diagnosed, and treated early, we would propose to have more programs that are similar to WISEWOMAN to leverage existing national breast and cervical detection programs for CVD screening.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search using Scopus, Embase, PubMed, ProQuest, Web of Science, Psycinfo, and Cinahl from January 2000 onwards. In addition, we also reviewed gray literature for potential recommendations and policy statements. The references of all included studies were also visually screened for potentially relevant studies. Corresponding authors were contacted when full-text access was unavailable. The search was completed on 31st December 2022. Only English-language publications were reviewed. The search strategy, developed by the authors whose expertise included public health, public policy and cardiology, was also reviewed by the medical librarian, in order to ensure incorporation of all relevant concepts on the subject matter. The key concepts for the search were “women” and “heart health” or “cardiovascular disease” combined with “prevention” and “policies”, “laws”, “or regulations”. The concepts were combined with Boolean operators “AND,” and “OR,”. The detailed search strategy and search strings can be found in Supplementary Table 11.

For the first stage of the search, authors CW, SW, LW reviewed the title and abstract of the first 10% of the articles (1363 papers) independently and compared to ensure there was at least 90% agreement prior to dividing the remainder and continuing the rest of the selection process. All differences in judgements were discussed to ensure that inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied similarly among them. For the second stage, full-text retrieval was done for publications that were selected on the initial screen and those that were unable to be conclusively excluded based on title and abstract alone.

The conduct and reporting of this systematic review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines and checklist (Supplementary Table 12)175.

Selection criteria

Articles were included if they focused on the primary prevention of CVD in adult women, particularly CHD, and included policies, directives, and potential policy-altering recommendations. Publications where women’s heart health was not the sole focus or part of a larger review or study relating to CVD, were included if there was at least a distinct section dedicated to women. Thus, while we acknowledge that population level interventions such as policies addressing alcohol or air pollution benefit women as well, it is not within the scope of our review to discuss these policies if they were not addressed directly to women. Policies involve a series of decisions that define a goal and a set of means to achieve it. They can include regulation, legislation, procedure, administrative action, incentive or voluntary practice176,177. Articles were excluded if they lacked a separate section or focus on heart health for women, or if they described pathophysiology, treatment, or interventions solely without any implementation recommendations. All disagreements and uncertainties were resolved through regular author meetings and discussions.

Data extraction and analysis

The authors agreed upon the information required for extraction and developed a standardized electronic data sheet so that the authors were able to simultaneously work on it. One of the writers independently evaluated each of the full text reviews, and a second reviewer confirmed the conclusions. Whenever there was discordance, the disagreement was resolved by a third reviewer and by consensus.

Using the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklists178,179,180,181,182, the relevant tool to match the article type, was used to appraise the articles’ quality as either high, moderate, or low. A study was classified as having high methodological quality if it had a score higher than 70%, medium quality if it received a score between 40% and 70%, and low quality if it received a score of less than 40%183.

Using a life course approach to chronic disease184, we classified the clinical directives based on periods throughout a woman’s life starting from puberty to menopause and old age. We did not include during gestational period or childhood as these policies do not take a gender or sex approach due to the lesser-known impact of sex during these phases. Subsequently, we integrated the recommendations into the public health typology model185, which classifies public health recommendations and policy as either being direct actions or indirect actions of public health interventions (Supplementary Table 10). Direct actions refer to interventions directed towards the population. Indirection actions refer to actions targeted towards third parties and include advocating, supporting, and collaborating. By combining these frameworks, we created our data sheet for extraction. The data extraction form included the following details: author, title, year of publication, country, study design or type, brief description of the articles, recommendations by the author or policies responding to CVD issues, primary and secondary intervention types towards CVD risk and the methods of intervention.

Responses