Prognostic impact of expression of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30 in/on mast cells in systemic mastocytosis: a registry study of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis

Introduction

Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is a cluster of rare and heterogeneous neoplasms defined by an accumulation of clonal mast cells (MC) in several organs and tissues, such as bone marrow (BM), spleen, liver, lymph nodes and/or gastrointestinal (GI) tract. In most patients, the disease is driven by an activating somatic point mutation in the KIT gene leading to a constitutive activation of the KIT receptor [1,2,3,4].

Like previous classification proposals, the 5th edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) divides mastocytosis into cutaneous mastocytosis (CM), SM and localized MC tumors [4,5,6]. SM is further split into six subtypes: bone marrow mastocytosis (BMM), indolent SM (ISM), smoldering SM (SSM), aggressive SM (ASM), SM with an associated hematologic neoplasm (SM-AHN) and MC leukemia (MCL). Whereas BMM, ISM and SSM are collectively termed non-advanced SM, ASM, SM-AHN and MCL are collectively named advanced SM (advSM). The International Consensus Classification (ICC) proposed a similar classification [7]. Furthermore, in contrast to the WHO proposal, the ICC proposal still regards BMM as a provisional sub-variant of ISM.

Since 2001, the diagnosis of SM is based on histology and morphology as well as molecular and phenotypic criteria [1,2,3,4]. The major diagnostic SM criterion is the presence of multifocal dense infiltrates of MC (≥15 MC in aggregates) staining positive for tryptase and/or KIT (CD117) in BM sections or in other extracutaneous organ(s) [1,2,3,4,5]. There are four minor diagnostic SM criteria. First, in BM smears or biopsy sections of BM or other extracutaneous organs, >25% of MC are spindle-shaped or have an atypical immature morphology. Second, MC in the BM, peripheral blood (PB), or other extracutaneous organs express CD2, CD25 and/or CD30. The detection of these antigens is accomplished either by flow cytometry and/or immunohistochemistry (IHC). Third, detecting a KIT D816V mutation or other KIT-activating KIT mutation in the BM, PB, or other extracutaneous organs [8, 9]. Fourth, persistent elevation of the basal serum tryptase (BST) level > 20 ng/ml, unless there is an associated myeloid neoplasm—in this case an elevated tryptase level does not count as a minor SM criterion [4, 7]. In the presence of hereditary alpha tryptasemia, the tryptase level should be divided by the total copy numbers of the alpha tryptase gene [4, 10].

In most patients with SM, expression of CD2, CD25 and/or CD30 in/on MC is demonstrable [11,12,13]. In some subsets of SM, like well-differentiated SM (WDSM), MC only display CD30 but stain negative for CD2 and CD25 which highlights the importance of CD30 as a novel diagnostic marker in SM contexts [4]. However, in most patients with SM, co-expression of CD25 and CD30 and sometimes also CD2 is the typical immunophenotypic profile of neoplastic MC [1,2,3,4,5]. By contrast, normal MC usually lack CD2, CD25 and CD30 [14, 15].

In the context of ISM, CD2 seems to be a recurrent aberrant and functionally relevant marker of neoplastic MC [1,2,3,4, 16, 17]. It is also worth noting that CD2, known as lymphocyte function antigen 2 (LFA-2), mediates adhesion and homotypic aggregation of MC through interaction and binding to its counter-receptor LFA-3 (CD58) displayed by neoplastic and normal MC [17, 18].

However, so far, little is known about the prognostic impact of aberrantly expressed cell surface antigens on MC in SM. Previous studies described a rough correlation between (strong cytoplasmic and surface) CD30 expression and advSM [19]. However, later, it turned out that CD30 is also expressed in MC in most patients with ISM and that in several patients with advSM, MC stain negative for CD30 [20,21,22].

In other studies, CD2 was expressed preferentially on MC of patients with ISM [6] and in some cases, CD2 expression on MC decreased in the follow-up when the disease progressed to ASM or MCL [23]. It has also been discussed that the lack of CD2 might be associated with a loss of focal MC aggregation and thus leukemic expansion [17, 18].

The aim of the present study was to explore the prognostic impact of expression of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30 in MC in patients with SM. To address this issue, we examined 5034 patients with MC disorders collected in the registry of the European Competence Network on Mastocytosis (ECNM).

Methods

Patients in the ECNM registry

In 2012, the ECNM registry was established as a multicenter observational study approach. Details about the ECNM registry, including study design, eligibility criteria, age limits, disease classifications and characteristics, ethical approval and informed consent have been published elsewhere [24] and have been recently updated [25, 26]. Data analyzed in this project were extracted from the seventh data wave set of the ECNM registry, including 5034 patients with MC disorders collected in 31 European centers and one in the United States, the Stanford Cancer Institute [24, 25]. The ECNM registry data set contains clinical, laboratory and follow-up (FU) data and all clinical endpoints relevant to prognostication. The study was conducted in compliance with the protocol and adhered to the current version of the ethical principles for medical research summarized in the Declaration of Helsinki. Local ethics committees gave approval and all national legal and regulatory requirements were met. All patients provided written informed consent prior to inclusion into the ECNM registry. Details about the ECNM and ECNM registry are described in the supplement.

Analysis of expression of CD2, CD25, and CD30 in MC

Patients with a confirmed diagnosis of SM according to the WHO classification and a FU of at least three months were minimal requirements sufficient for enrollment and analysis. Expression of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30 in/on MC using either flow cytometry of BM aspirates and/or IHC of BM biopsy sections (and/or biopsy material of other involved organs) was performed at diagnosis and during FU. The following aberrancy patterns of MC were defined: co-expression of CD2 and CD25, co-expression of CD2 and CD30, co-expression of CD25 and CD30, and co-expression of all three markers (CD2, CD25 and CD30) in/on MC. Information about expression of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30 was available only in a minority of patients with SM. Subsequently, we analyzed the following MC patterns and correlations with clinical outcomes in various patient groups: CD2+/CD25+ MC, CD2–/CD25+ MC, CD2+/CD25– MC, and CD2–/CD25– MC.

Determining associations between surface marker expression and disease-related parameters

Expression of CD2, CD25, and CD30 in/on MC was correlated with specific disease-related clinical parameters such as the size of the spleen, liver and lymph nodes, MC mediator-related symptoms including allergies, anaphylaxis, flushing, pruritus and blistering / bullae as well as constitutional / cardiovascular symptoms, symptoms of SM-related osteopathy (osteopenia or osteoporosis), and other organ manifestations such as gastrointestinal tract symptoms. In addition, expression of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30 was correlated with OS, progression-free survival (PFS) and event-free survival (EFS). Finally, surface antigen expression in MC was correlated with clinically relevant and comparable laboratory parameters such as values of basal serum tryptase, mutational status, and chromosomal aberrations. Details are described in the supplement.

Statistical analysis

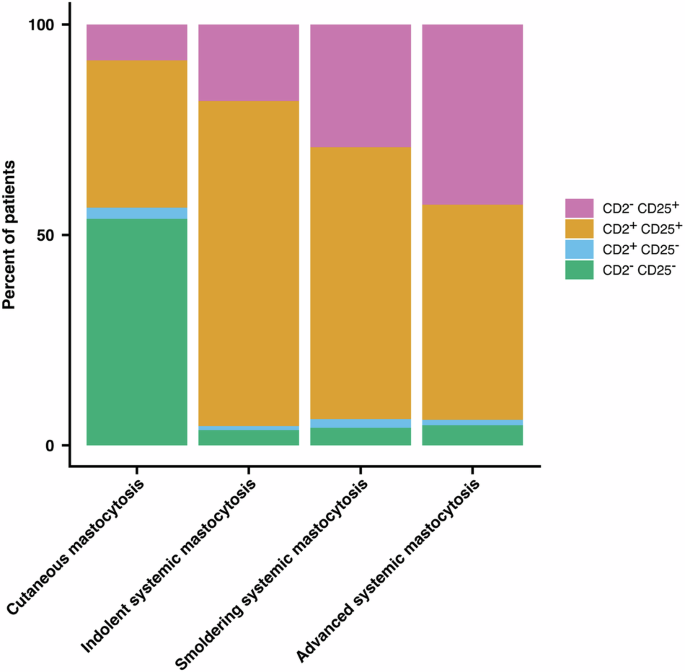

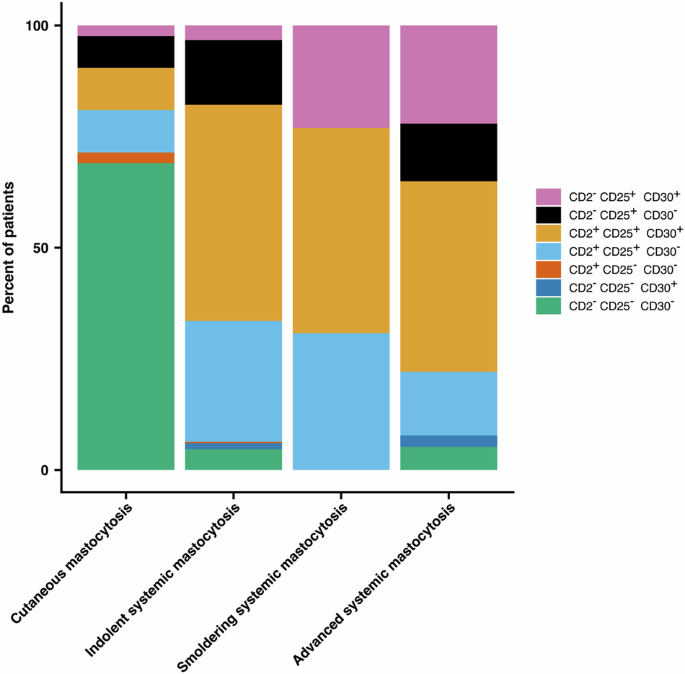

Surface expression of CD2 and CD25 as well as of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30 by flow cytometry and/or IHC was analyzed in four MC disease entities: CM, ISM (including BMM), SSM, and advSM. To illustrate the patterns of abnormally expressed antigens (CD2, CD25, CD30) in/on MC in various disease entities, stacked bar plots were created.

Survival time was calculated from the date of the first visit to either the date of death or the last FU visit recorded in the ECNM registry. To investigate the survival Kaplan-Meier curves were created for OS, PFS (time from diagnosis to progression), and EFS (time from diagnosis to progression or death). PFS was defined as progression from CM to SM, ISM to SSM or advSM, and SSM to advSM. Kaplan-Meier curves for survival probabilities were constructed and stratified by patterns of expression of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30. A log-rank test was employed to assess differences in survival time among ISM, SSM and advSM. P values below 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The assumption of proportional hazards was tested by visual inspection of the log-log plots. Additionally, we constructed multivariate Cox-proportional hazard models including CD2 expression, CD25 expression, age at inclusion, and sex.

To test for an association between the antigen expression and the presence of extramedullary involvement (splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and lymphadenopathy) a multivariate logistic regression was created. Extramedullary involvement was used as the dependent variable and CD2-negativity and CD25-positivity as independent variables. The models were additionally adjusted for sex and age of the patients at inclusion. Similar models were also created to test the association with the most important MC mediator-related symptoms. Coefficients were transformed to odds ratios and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Multicollinearity was checked visually and by calculating the variance inflation factor (VIF). A VIF < 5 indicates a low correlation between the predictors (Supplementary Table S1). A Wilcoxon-signed-rank test was applied to compare the baseline serum tryptase levels in patients with and without CD2 expression. We used an additional multivariate logistic regression model to test the association between antigen expression and mutations in the KIT gene, genes other than KIT, and karyotype with conventional cytogenetic analysis.

All statistical analyses were conducted utilizing various R packages, including ‘dplyr,’ ‘ggplot2,’ ‘ggpubr,’ ‘survival,’ and ‘survminer,’ within the R version 4.3.1 environment (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Characteristics of patients and available data on surface marker expression

Of the 5034 patients with MC disorders available for analysis in the data set of the ECNM registry, 2531 patients with SM were identified in whom at least one CD marker (CD2, CD25, or CD30) was analyzed in/on MC by flow cytometry and/or IHC.

Most of these patients had ISM. In fact, within the group of ISM, marker studies were performed in 2008 patients (79.6% of all ISM patients). This was followed by patients with advSM (458 patients, 77.6% of all cases with advSM) and SSM (65 patients, 77.3% of all patients with SSM). The 458 patients with advSM were diagnosed to have ASM (n = 110), SM-AHN (n = 307), or MCL (n = 41).

Demographic and laboratory variables of patients are summarized in Table 1. Patients with ISM were younger with a median age of 47 years compared to advSM (median age of 64 years). There was a preponderance of male sex in patients with advSM (284 male patients, 62% of patients with advSM; 174 female patients, 38% of patients with advSM) compared to ISM (893 male patients, 44.5% of patients with ISM; 1115 female patients, 55.5% of patients with ISM). Regarding data availability of expression of CD2, CD25 and CD30 in/on MC in patients with SM, CD2 was available in 75.8% of cases, CD25 in 94.6%, and CD30 in 23.5% of SM patients (Table 1).

Expression of CD2 is associated with non-advanced SM, whereas lack of CD2 expression is often found in advSM

Results of both CD2 and CD25 by flow cytometry and/or IHC were available in 2225 patients (44.25%).

In patients with SM in whom MC expressed CD25, lack of expression of CD2 was recorded in 290 of 1522 patients with ISM (19.05%), in 14 of 45 patients with SSM (31.11%) and in 134 of 294 patients with advSM (45.58%). Among these cases with advSM and CD25 in/on MC, lack of CD2 in/on MC was found in 24/67 patients (35.82%) with ASM, 102/201 (50.75%) with SM-AHN, and 8/26 (30.77%) in patients with MCL. On the other hand, expression of CD2 in MC was found in 1232 of 1522 patients (80.95%) with ISM, in 31 of 45 patients (68.89%) with SSM and in 160 of 294 patients (54.42%) with advSM. In fact, in most patients with ISM, MC were found to express CD2 and CD25, whereas in patients with SSM and advSM, MC often failed to display CD2 but still expressed CD25 (Fig. 1, Table 2).

Expression of CD2 and CD25 in or on bone marrow MC was determined by flow cytometry and/or immunohistochemistry in 2225 patients (44.25%) with mastocytosis and available results of CD2 and CD25 expression, including cutaneous mastocytosis (CM, n = 221), indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM, n = 1595), smoldering systemic mastocytosis (SSM, n = 48), and advanced systemic mastocytosis (advSM, n = 313). In most patients with ISM, MC expressed both CD2 and CD25. However, whereas in a considerable number of patients with SSM and advSM, MC did not express CD2 but still expressed CD25. In very few patients with SM, MC were found to lack CD2 and CD25. MC mast cells.

Lack of CD2-expression in MC is indicative of a poor prognosis in SM

Survival analysis was performed in 1183 patients with available results of expression of CD2 and CD25 in MC as well as of survival time data. Survival analysis was performed in patients alive with a date of last FU.

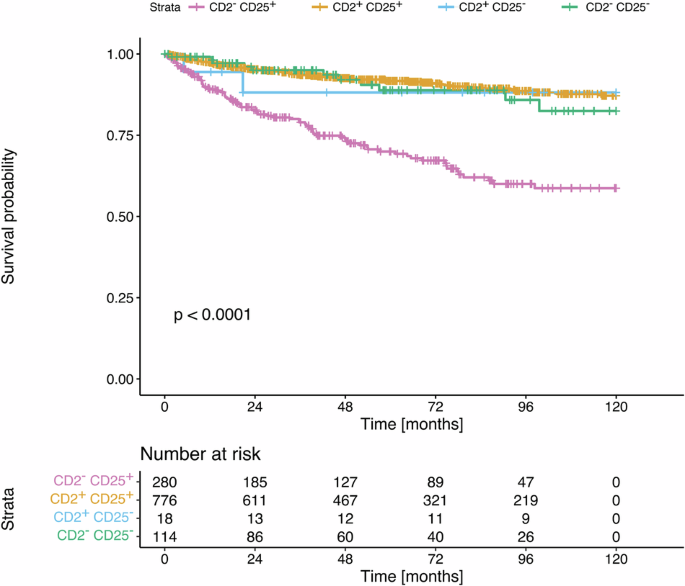

When examining all patients with SM (non-advanced SM and advSM), we found a significantly reduced OS in patients with CD2-negative MC expressing CD25 compared to patients in whom MC expressed both CD2 and CD25. Moreover, a significantly shorter OS was found when comparing SM patients with CD2-negative MC with patients in whom MC expressed CD2 but did not co-express CD25 (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2).

OS was analyzed in a univariate analysis in 1183 patients with SM in whom FU and survival data were reported and results by flow cytometry and/or immunohistochemistry for CD2 expression and CD25 expression on/in MC were available. Four groups of patients were examined based on the pattern of CD2 and CD25 expression on/in MC: CD2–/CD25+ MC, CD2+/CD25+ MC, CD2+/CD25– MC; and CD2–/CD25– MC. The probability of OS in these 4 groups of patients was determined according to the method of Kaplan and Meier. Patients with CD2-negative MC expressing CD25 had a significantly reduced OS compared to patients with MC expressing both, CD2 and CD25. Patients with CD2-negative MC had a significantly shorter OS compared to patients in whom MC expressed CD2 without co-expressing CD25 (p < 0.0001). The p value refers to the comparison of all survival curves as assessed by log-rank test. SM systemic mastocytosis, FU follow-up, MC mast cells.

In a next step, stratification of CD2 expression analysis was done according to the three different disease entities ISM, SSM and advSM. There was a statistically significant reduction in OS in patients with ISM and advSM with CD2-negative MC compared to patients with CD2-positive MC (p = 0.018, and p = 0.012, respectively). Although there was a trend to a reduced OS in patients with SSM and CD2-negative MC, this difference did not reach statistical significance because of the small number of patients (Supplementary Figs. S1a–c). In fact, because of the small number of patients in all three entities of advSM, ASM, SM-AHN and MCL, a separate statistical analysis would interfere with power and would not provide clinically meaningful results.

Next, we examined PFS and EFS and both were considerably influenced by CD2 expression in/on MC in ISM and advSM (Supplementary Figs. S2, S3, Supplementary Figs. S5, S6). When examining all patients with SM, there was a significantly reduced PFS in patients with CD2-negative MC expressing CD25 compared to patients with co-expression of CD2 and CD25 in/on MC (p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. S4). Also, the EFS was significantly reduced in patients with MC not expressing CD2 but expressing CD25 compared to MC with co-expression of CD2 and CD25 (p < 0.0001) (Supplementary Fig. S7).

Looking at different MC disease entities, this significant difference in PFS and EFS influenced by CD2-expression was present in ISM, whereas in SSM – although there was a trend—and in advSM this difference in PFS and EFS was not statistically significant.

In a final step, we applied multivariate analysis using CD2 expression, CD25 expression, age and sex of patients. In these studies, the predictive power of lack of CD2 expression was maintained regarding OS, PFS and EFS for the total cohort of all patients with SM as well as in patients with ISM. However, in SSM and advSM the predictive power of lack of CD2 expression regarding OS, PFS and EFS was lost (Supplementary Tables S2a–d; S3a–d and S4a–d).

We also employed prognostic markers that were available in at least 10% of all patients, including age, extramedullary involvement, albumin, LDH and BST, in patients with ISM and lack of CD2 expression of MC in a univariate and multivariate analysis, using these prognostic variables as non-imputed data. We found that lack of CD2 expression of MC was an independent prognostic variable concerning OS, PFS and EFS in this cohort of patients with ISM (Supplementary Tables S5a–c).

Death in patients with ISM was significantly less disease related compared to patients with SSM and advSM, although power of statistical analysis is limited due to small number of cases (Supplementary Table S6).

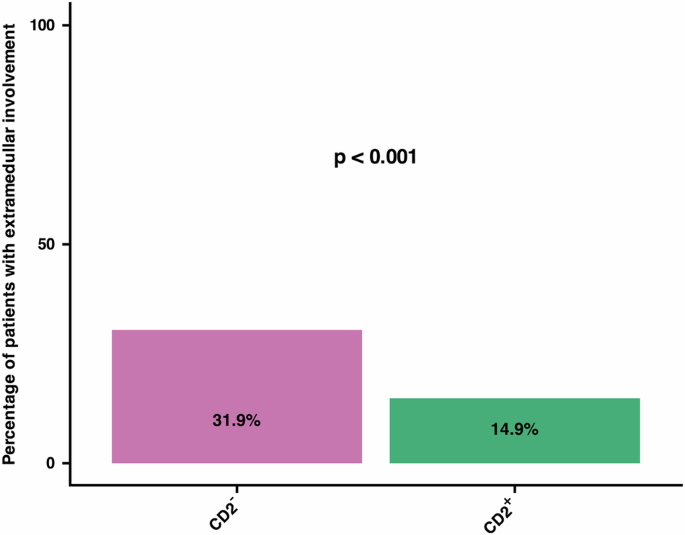

Lack of CD2 expression in MC is associated with extramedullary involvement in SM

Malignant expansion of mobilized MC in advSM often involves extramedullary organs, such as the spleen, liver, and/or lymph nodes. Therefore, we asked whether CD2-negativity in/on MC in SM is associated with an extramedullary spread of these cells and/or with splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and/or lymphadenopathy, defined as palpable lymph nodes or lymph nodes >2 cm in size in sonography or computed tomography. Logistic regression analysis, taking into account the absent expression of CD2, expression of CD25, age and sex, with the outcome of extramedullary involvement, revealed that patients with CD2-negative MC have a 2.63 higher odds ratio of extramedullary involvement compared to patients with CD2-positive MC (Table 3). In fact, in SM patients with CD2-negative MC, 31.9% had extramedullary involvement, whereas in patients with CD2-positive MC extramedullary involvement was only found in 14.9% (Fig. 3).

The two bars reflect the percentage of patients with SM according to the CD2 expression status in MC. In SM patients with CD2-negative MC, 31.9% had extramedullary involvement, whereas in SM patients with CD2-positive MC extramedullary involvement was only found in 14.9%. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001). SM systemic mastocytosis, MC mast cells.

We also examined patients with non-advanced SM and advSM separately regarding the impact of lack of CD2 expression in/on MC on extramedullary involvement. In most patients with non-advanced SM (n = 25, 6.5%), there was only one extramedullary organ effected, whereas in a majority of patients with advSM (n = 25, 30.1%) all three organs, spleen, liver and lymph nodes, were affected.

Associations between expression of aberrant CD2 and CD25 in MC with other clinical and laboratory parameters

Logistic regression models were created to examine the association between CD2 expression and CD25 expression with clinical parameters in SM, adjusted for age and sex (Supplementary Tables S7, S8). CD2-negativity of MC was associated with lower rates of allergies (Odds Ratio (OR): 0.53; 95% CI 0.42, 0.67; p < 0.001), constitutional/cardiovascular symptoms (OR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.50, 0.84; p = 0.001), and SM-related osteopathy (osteopenia or osteoporosis) (OR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.49, 0.79; p < 0.001). By contrast, we found no associations between CD2-negativity of MC and the presence of pruritus, blistering/bullae, or gastrointestinal symptoms in our SM patients. CD25-positivity did not show significant associations with any of the aforementioned clinical parameters (Supplementary Figs. S8–S13).

We also performed univariate and multivariate analyses to detect possible associations between expression of CD2 and CD25 in/on MC and SM-related laboratory parameters, such as mutational status with KIT D816V mutation, other activating KIT mutation, mutations in genes other than KIT in molecular genetic analysis, and chromosomal aberrations in cytogenetic analysis. There was a statistically significant association between CD2-negative MC and mutations in genes other than KIT (p = 0.011) with an OR of 7.54. Ultimately, there was a positive association between CD2-negative MC and an abnormal karyotype with conventional cytogenetic analysis, although this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.4) (Supplementary Table S9).

There was an association between CD2-negativity of MC and basal serum tryptase. The median basal serum tryptase was 40.55 µg/l (Interquartile range (IQR): 21.00, 102.00) and 29.00 µg/l (IQR: 17.00, 63.40), in 531 patients with CD2-negative MC and in 1441 patients with CD2-positive MC, respectively (p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. S14). Patients with lack of CD2 expression of MC had a significantly higher median serum tryptase levels compared to patients in whom MC were found to express CD2 (Supplementary Fig. S15). The Wilcoxon-signed-rank test did not reveal a statistically significant difference between patients with CD25-positive (median: 32.40 µg/l, IQR: 19.00, 78.95) and CD25-negative (median: 31.00, IQR: 15.38, 61.48) MC (p = 0.109).

The expression or lack of CD30 in MC is not associated with advSM and does not interfere with the prognostic impact of CD2-negativity of MC in SM patients

Results of expression of all three markers, CD2, CD25, and CD30, by flow cytometry and/or IHC were available in 506 patients (10.05%). This includes 42 patients with CM and ten with “mastocytosis in the skin”. In these patients with availability of all three mentioned markers, expression of CD30 on MC was tested in 364/2008 patients with ISM, 13/65 patients with SSM, and 77/458 patients with advSM (Fig. 4, Table 4). Comparing ISM with advSM, the proportion of cases with CD2–, CD25+ and CD30+ MC was considerably lower in patients with ISM. On the other hand, the percentage of patients in whom MC displayed the aberrancy pattern CD2+, CD25+, CD30– or the pattern CD2+, CD25+, CD30+ was considerably higher in patients with ISM compared to patients with advSM. There was no difference in the percentage of cases where MC exhibited the aberration profile CD2+, CD25+, CD30+ when comparing ISM, SSM, and advSM.

Expression of CD2, CD25, and CD30 in or on bone marrow MC was determined by flow cytometry and/or immunohistochemistry in 506 patients (10.95%) with mastocytosis, including cutaneous mastocytosis (CM, n = 42), “mastocytosis in the skin” (MIS, n = 10), indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM, n = 364), smoldering systemic mastocytosis (SSM, n = 13), and advanced systemic mastocytosis (advSM, n = 77). In patients with ISM, MC expressed both CD2 and CD25, with or without CD30 expression, in a considerably higher number compared to patients with advSM. However, in patients with ISM there was a lower percentage of patients not expressing CD2 but still expressing CD25 and CD30, compared to SSM and advSM. In very few patients with SM, MC were found to lack CD2 and CD25, regardless of CD30 expression. MC mast cells.

Analyzing patients with CD30 expression only without analysis of CD2 and CD25 expression at the same time, there was CD30 expression in 224/428 patients with ISM (52.34%), in 12/18 patients with SSM (66.67%), and in 67/111 patients with advSM (67.68%). The difference between these groups of MC disorders was statistically significant (p = 0.014).

Discussion

The expression of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30 in/on MC in extracutaneous organ(s) is a minor diagnostic SM criterion in the WHO classification and the ICC [4,5,6,7]. And although it has been suggested that the loss of CD2 expression is associated with a more aggressive course of MC disease, there are no data suggesting a significant prognostic impact of expression or lack of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30 in/on MC in patients with SM [23]. To address this issue we retrospectively analyzed the impact of the expression/lack of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30, assessed by flow cytometry and/or IHC, on the prognosis of our SM patients collected in the ECNM registry.

When analyzing patients with SM and the availability of at least one CD marker (CD2, CD25, or CD30), we found that in patients with ISM in whom MC expressed CD25, there was a considerably higher proportion of patients with CD2-positive MC and a considerably lower proportion of cases with CD2-negative MC compared to patients with advSM. In most patients with ISM MC were found to co-express CD2 and CD25, whereas in advanced MC diseases, MC were often found to lack CD2 expression but still expressed CD25. These data suggest that in SM with CD25-positive MC, CD2 expression is associated with non-advanced SM, whereas lack of expression of CD2 in/on MC may be indicative of advSM [19, 26]. However, although an association between CD2-negative MC and advSM was found, we also identified patients with advSM in whom MC displayed both CD2 and CD25.

In a next step we examined associations between CD2 expression in MC and the prognosis of our SM patients. In these studies we found a significantly reduced OS, PFS and EFS in SM patients with CD2-negative MC compared to patients with SM in whom MC expressed CD2. Analyzing different variants of SM, ISM patients and advSM patients with CD2-negative MC had a significantly reduced OS compared to patients with CD2-positive MC. We also found a trend towards reduced OS in SSM patients with CD2-negative MC compared to those in whom MC exhibited CD2. However, statistical significance was not reached due to the small numbers of patients.

We next asked whether CD2-negativity of MC is an independent prognostic variable. In a multivariate analysis, the prognostic power of lack of CD2 expression in MC was maintained for all survival parameters for the total cohort of patients with SM and especially for patients with ISM, which is by far the most frequent disease entity among systemic MC diseases. However, in patients with advSM, low CD2 expression in/on MC was not identified as an independent prognostic variable, which may have several explanations. First, it may be due to the low numbers of patients included in the advSM group. In addition, advSM is a complex, malignant neoplasm where the relative prognostic power of individual variables may be weaker compared to ISM. Moreover, lack or loss of CD2 may be an early event in ISM that may lead to a stepwise disintegration and leukemic spread of neoplastic MC, whereas in advSM several additional mechanisms also contribute to disease progression and poor prognosis. Finally, patients with advSM are often treated with disease-modifying drugs, such as KIT-targeting tyrosine kinase inhibitors or stem cell transplantation. As a result, patients with advSM may nowadays have a better prognosis and improved survival independent of expression or lack of CD2 in/on MC compared to previous years, and even patients with MCL, where a huge leukemic spread of MC is often seen, may respond nicely to these therapies. In a recent publication median OS was significantly shorter in midostaurin-treated patients with advSM and lack of CD2 expression, although in a multivariate analysis CD2 expression lost its prognostic significance [27].

CD2, known as LFA-2, is a transmembrane adhesion molecule implicated in adhesion and homotypic aggregation of cells expressing CD2-counter-receptors. MC reportedly express CD58, also termed LFA-3, a well-known receptor of CD2. Based on this notion and the observation, that lack or loss of CD2 is associated with disaggregation and leukemic dissemination of MC, we asked whether CD2-negativity of MC in our patients is associated with signs of extramedullary dissemination and a leukemic spread of MC. Indeed, we found a 2.63 higher odds ratio of extramedullary involvement, manifesting as splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, and/or lymphadenopathy, in patients with SM in whom MC did not express CD2, compared to SM patients in whom MC displayed CD2. By contrast, we did not find an association between CD2-negativity of MC and the diagnosis of MCL. This may be due to the low number of MCL patients identified in the ECNM registry. An alternative explanation may be that lack of CD2 on MC is not only associated with a more leukemic spread of MC but also with subsequent redistribution to other extramedullary sites where other homing receptors and molecules play an important role in MC invasion. This hypothesis would also be in line with our observation that lack of CD2 on MC is associated with more extramedullary disease in patients with advSM.

Absence of expression of CD2 in MC was also found to be associated with a reduced rate of allergies, constitutional/cardiovascular symptoms and SM-related bone disease with osteopenia and osteoporosis. This is in contrast with the grade of pruritus, blistering/bullae, or gastrointestinal symptoms, where there was no such association. The expression of CD25 on MC was not significantly associated with any of these clinical parameters.

So far, the mechanisms underlying the correlation between CD2-negativity and the low rates of allergies and constitutional/cardiovascular symptoms remain unknown. One possibility could be that direct cell-cell contact of MC in aggregates or even CD2-CD58 interactions among MC plays a role in MC activation. Another explanation would be that in the SM context, CD2-negative MC are more immature and therefore less potent in producing and releasing mediators of allergy. In this regard it is worth noting that lack of expression of CD2 in/on MC is often associated with a more advanced MC disorder. In patients with advSM, signs of BM dysfunction and other organ damage, including osteolytic lesions, are more common compared to patients with non-advanced SM, where allergies, constitutional/cardiovascular symptoms as well as osteopenia and osteoporosis are more frequently recorded in patients with non-advanced SM compared to patients with advSM.

We also found an association between serum tryptase levels and CD2-negative MC in our SM patients. In particular, the median tryptase level was significantly higher in patients with CD2-negative MC compared to SM patients in whom MC expressed CD2. Again, lack of CD2 expression is a sign of more advanced SM, and these patients have a higher BST level which is usually indicative of a higher MC burden. There was also a statistically significant association between patients with CD2-negative MC and the presence of mutations in genes other than KIT, indicating a more advanced and prognostically worse SM variant. This aligns with the observation that such gene mutations, especially mutations in SRSF2, ASXL1, and/or RUNX1, are associated with poor prognosis [28]. And there was an—statistically not significant—association between CD2-negativity in MC and an abnormal karyotype. These associations may not have reached statistical significance because of the low number of patients in whom karyotypes were reported.

Several prognostic parameters have been related to survival in SM. We asked whether lack of CD2 in MC could be related to a poor survival in our SM patients. Indeed, we found that lack of expression of CD2 in MC in our patients with SM (all SM patients) and ISM is associated with a significantly reduced OS, PFS and EFS in univariate and multivariate analysis. In addition, we found in all SM patients with CD2-negativity of MC a 2.63 higher odds ratio of extramedullary involvement of spleen, liver, and/or lymph nodes. Whereas 31.9% of our SM patients with CD2-negative MC had extramedullary involvement, only 14.9% of our SM patients with CD2-positive MC showed extramedullary involvement. In this regard, it is noteworthy that extramedullary involvement is of prognostic relevance, as the number of organomegalies is adversely associated with OS [29].

Our ECNM registry study has several limitations. As a retrospective study there are potential biases with regard to patient selection and data collection. The expression of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30 in MC was usually evaluated once at diagnosis of SM by flow cytometry and/or IHC. It is, therefore, a static marker, not taking into account possible dynamic changes of antigen expression during the course of the MC disease and especially when the transformation from one entity to another occurs. The expression of CD2 was evaluated by flow cytometry, whereas the expression of CD25 and CD30 was evaluated either by flow cytometry and/or IHC. Nevertheless, it seems unlikely that our statements on the prognostic value of these markers, especially CD2, have been influenced by these two different methods, flow cytometry being the more sensitive analysis. Positivity or negativity of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30 are qualitative statements, therefore we can’t comment on the intenseness of signals, especially regarding age. There is no compulsory standard set of data on the expression of CD2, CD25, and/or CD30 in the registry, and WHO and ICC introduced CD30 expression as a diagnostic minor criterion only in 2022 into the recent mast cell disease classification. Therefore, one should interpret single-marker associations with caution [30].

Three aberrant markers were analyzed in our study, but only abnormal (low) expression of CD2 in MC appeared to be associated with prognosis, whereas CD25 and CD30 expression (or lack of expression) in/on MC was not associated with a particular prognosis. It is worth noting in this regard that of the three surface receptors tested, only CD2 is a known adhesion-mediating antigen on MC. The functional role of CD25 and CD30 on neoplastic MC remains unknown. In chronic myeloid leukemia, CD25 may sometimes act as a tumor-suppressor antigen [31]. However, in the SM context, CD25 has not been described to act as an inhibitory receptor in MC, which is in line with our observation that CD25 expression on MC is not associated with a particular WHO group or prognostic subset of SM.

All in all, our retrospective analysis shows that lack of CD2 in MC is associated with advSM and poor prognosis. However, whether CD2 is indeed a predictive marker that can be used to adjust management in patients with SM during FU in daily clinical practice, remains to be shown in controlled clinical validation studies.

It will also be crucial to put the lack of CD2 expression in/on MC into context with other known prognostic markers in SM, such as age, alkaline phosphatase, β2-microglobulin, albumin and genetic markers as well as risk scores such as MARS, a mutation-adjusted risk score for advSM [28].

In conclusion, lack of expression of CD2 in MC is associated with advSM, extramedullary disease spread, and a poor prognosis. Future research is needed to evaluate this finding as a possible supportive element in the management of SM patients.

Responses