Programmable solid-state condensates for spatiotemporal control of mammalian gene expression

Main

Synthetic biology aims to achieve robust, convenient and on-demand control over cell behavior, allowing various external control signals to precisely modulate specific gene expression programs in a trigger-inducible manner1,2,3. In the past decades, a multitude of ligand-dependent gene switches have been successfully engineered in mammalian cells3,4, enabling different types of trigger signals (for example, small molecules4,5,6,7, light8,9,10,11 or ultrasound12) to regulate target gene expression at the transcriptional8,9,12, translational6 or protein levels7,13. However, most of these systems are constructed on the basis of repetitive but yet unpredictable ‘trial-and-error’ methods4,14,15, as new regulatory relationships must often be carefully redesigned to allow the same chemical inducer to regulate a different stage of gene expression and/or a different inducer to modulate the same control site4,16. Therefore, a systematic, scalable and universal design strategy showing standardized and predictable regulation performance and permitting flexible switching between inducers and gene expression stages with minimal site-specific and cell-type-specific constraints would be highly preferred14.

Biomolecular condensates, also known as membraneless organelles, are naturally evolved or designed supramolecular structures capable of sequestering proteins and/or RNA molecules through liquid–liquid phase separation17,18. While the native roles of such assemblies were primarily assigned to regulation of stress response, increase in enzymatic flux, compartmentalization or concentration of biochemical reactions and control of signal transduction19,20, rationally engineered ‘designer condensates’ with customized user-defined purposes are currently gaining momentum21. For example, researchers from various disciplines engineered synthetic condensate systems with diverse applications such as regulation of cell-surface signaling22, biosynthesis of noncanonical-amino-acid-containing proteins23,24, metabolic engineering25,26,27, chromatin restructuring28 and DNA live imaging29. Biomolecular condensates were also engineered to sequester and release synthetic protein or RNA cargos for gene expression control such as regulation of mRNA translation, CRISPR–Cas9 activity or intracellular signal transduction in mammalian cells18,30,31,32,33. However, most such approaches are restricted to the regulation of transgene activities at individual subcellular compartments, necessitating preintroduction of artificial, system-specific protein targets into cells. Control of endogenous gene and protein activities using synthetic biomolecular condensates, on the contrary, has remained a greater challenge.

Here, we describe a holistic approach for the rational design of different subcellularly localized synthetic condensates as a practical alternative to construct ligand-responsive gene switches operating at different levels of gene expression (Fig. 1a). First, we show that an Escherichia coli-derived lipoate-protein ligase A (LplA)34 not only forms stable condensate structures in mammalian cells but can also be flexibly tethered to different cellular compartments (that is, the nucleus, mitochondria and plasma membrane) in a trigger-inducible manner upon fusion to specific conditional protein dimerization systems. Next, we engineer synthetic ‘anchor proteins’ capable of simultaneously targeting various cellular compartments or gene products of interest and binding to engineered condensate scaffolds. Capitalizing on grazoprevir-dependent dissociation of ANR (apo NS3a reader) protein from and concomitant association of GNCR (grazoprevir–NS3a complex reader) to NS3a(H1) (refs. 35,36), NS3a(H1)-containing condensates were precisely navigated to different genomic, episomal or RNA sites through custom-designed anchor proteins harboring either GNCR or ANR domains, resulting in grazoprevir-inducible or grazoprevir-repressible regulation of various transcriptional or translational activities in mammalian cells without the need to redesign specific gene expression loci. For grazoprevir-dependent regulation of CRISPR–Cas9 activity, we show that nuclear condensates engineered to sequester target guide RNAs (gRNAs) through specific protein anchors resulted in high induction folds that compare favorably to state-of-the-art CRISPR-mediated transcriptional activation (CRISPRa) designs. For regulation of transcriptional activity, we show that recruitment of nuclear condensates to both transgenic and endogenous promoter regions resulted in similar fold changes of inducible silencing and derepression when directly compared to similar configurations that involve grazoprevir-dependent recruitment of a human Krüppel-associated box (KRAB) domain37. Lastly, we show that retention of mRNA molecules within synthetic condensate structures in the nucleus dramatically improves the efficacy for translational regulation when compared to conventional mindsets that focus on cytosolic regulation of translation. Collectively, we establish synthetic biomolecular condensates as a versatile strategy to systematically control mammalian gene expression at different stages of interest, describe an effective regulation alternative for translational control and provide a valuable addition to the mammalian cell engineering toolkit.

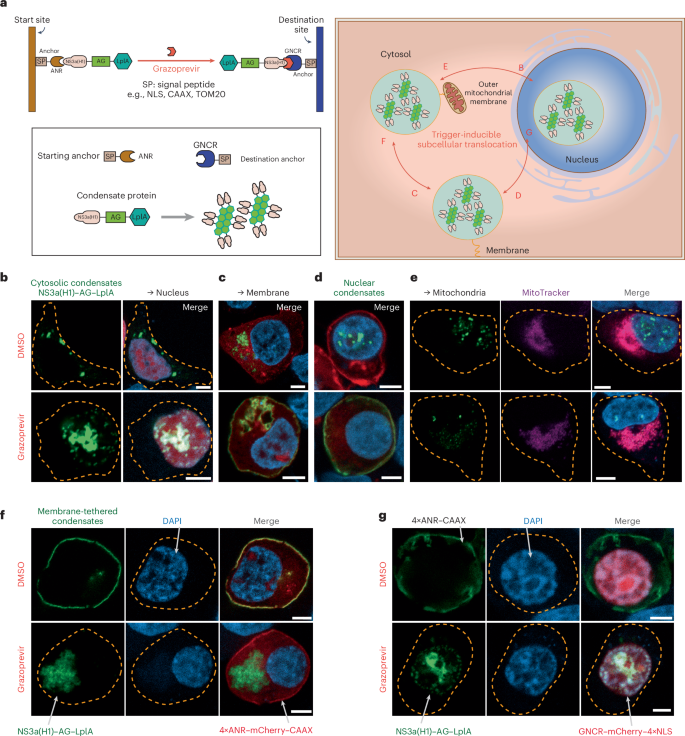

a, Trigger-inducible subcellular translocation of synthetic condensate formation. AG–LplA forms biomolecular condensates that are preferentially localized in the cytosol upon ectopic expression in mammalian cells. Fusion of AG–LplA to NS3a(H1) allows the Food and Drug Administration-approved drug grazoprevir to trigger subcellular migration of condensate formation from ANR-containing starting points to GNCR-containing destination sites created through fusion to various signal peptides (for example, NLS, prenylation motifs (CAAX) or a mitochondrial targeting signal (MTS or TOM20)). b, Grazoprevir-triggered nuclear translocation of cytosolic condensates (NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA, pYK91; GNCR–mCherry–4×NLS, pYK472). c, Grazoprevir-triggered membrane translocation of cytosolic condensates (NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA, pYK91; GNCR–mCherry–CAAX, pYK421). d, Grazoprevir-triggered membrane translocation of nuclear condensates (NLS–NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA, pYK163; GNCR–mCherry–CAAX, pYK421). e, Grazoprevir-triggered cytosolic translocation of nuclear condensates (NLS–NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA, pYK163; TOM20–GNCR–mCherry, pYK481). f, Cytosolic translocation of membrane-tethered condensates (NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA, pYK91; 4×ANR–mCherry–CAAX, pYK474). g, Nuclear translocation of membrane-tethered condensates (NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA, pYK91; GNCR–mCherry–4×NLS, pYK472; 4×ANR–CAAX, pYK506). DAPI (b–g) and MitoTracker (e) staining were performed and confocal imaging was conducted at 24 h after transfection in HEK-293 cells cultured with 1 µM grazoprevir or DMSO (control). The yellow dashed lines indicate cell membranes (scale bar, 5 µm). Images are representative of three independent experiments.

Results

Design and validation of spatially localized synthetic condensates

In a previous study, we reported that His-tag purified LplA protein from E. coli forms stable but reversible hydrogels at room temperature in vitro, with high LplA concentrations favoring its gelation34. However, whether proteins known to phase separate in test tubes would also retain their physicochemical properties in living cells remains a critical question for investigation19. Thus, we transfected GFP-tagged LplA into HEK-293 cells and found that only fusion proteins with LplA placed at the C terminus accounted for a small fraction of granule-like structures (Supplementary Fig. 1a). However, when we replaced EGFP with a tetrameric scaffold protein Azami green (AG) also producing green fluorescence and previously shown to improve phase-separation efficiency of protein-based hydrogels30,38, spontaneous condensate formation was effectively triggered by genetically encoded AG–LplA expression (Supplementary Fig. 1a,b).

While cytosolic condensates were already extensively explored to design control strategies for a variety of cellular functions18,30,31,32,33, rationally engineered condensates with the potential to translocate to other subcellular sites could substantially increase the application scope of this approach. Thus, we fused AG–LplA to hepatitis C virus-derived NS3a(H1) protein, which binds the synthetic ANR peptide with high affinity35,39, unless the presence of grazoprevir concomitantly disrupts the constitutive ANR–NS3a(H1) binding while triggering formation of stable GNCR–NS3a(H1) complexes36. Thus, NS3a(H1)-containing condensates (such as NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA) can be programmed to first reside at the ANR-containing starting site, allowing grazoprevir to trigger subcellular migration of condensate formation toward the GNCR-containing destination site (Fig. 1a). Because NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA preferentially forms cytoplasmic condensates (Supplementary Fig. 1a), regulation of nuclear translocation of cytoplasmic NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA is achieved through addition of an anchor protein tagged with a nuclear localization signal (GNCR–mCherry–4×NLS), such that formation of nuclear condensates becomes dependent on grazoprevir administration (Fig. 1b). Likewise, using prenylated GNCR–mCherry–CAAX as a destination anchor, cytoplasmic NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA can also be effectively controlled to translocate toward compartments of the cell’s secretory machinery (for example, the endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus or plasma membrane) in a grazoprevir-regulated manner (Fig. 1c). Notably, we show that NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA can also be completely tethered into the nucleus to spontaneously form nuclear condensates in the absence of grazoprevir (Fig. 1d), allowing grazoprevir to trigger translocation of NLS–NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA to the plasma membrane (Fig. 1d) or mitochondria (Fig. 1e) under the guidance of site-specific GNCR-containing destination anchors. Lastly, to show the simultaneous action of multiple anchor proteins, we first tethered NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA onto the plasma membrane through the codelivery of ANR-containing starting anchors (Fig. 1f,g). Thus, upon grazoprevir treatment, the choice of a site-specific destination anchor enabled precise control of whether membrane-tethered NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA would translocate into the cytosol (Fig. 1f) or nucleus (Fig. 1g). Collectively, these results show that NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA not only forms stable granule-like structures in both the cytosol and the nucleus (Supplementary Fig. 1a) but can also undergo chemically induced protein–protein interactions to respond to dynamic cellular or biochemical signals (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d). To probe the molecular dynamics of LplA-based condensates, fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) was further performed, indicating a very low level of exchangeability and reorganization of either nuclear or cytoplasmic NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA (Supplementary Figs. 1b and 3a). We also assessed the dynamics of cytosol-to-nucleus translocation of the LplA-based condensates, showing that an equilibrium was reached at approximately 12 h after grazoprevir stimulation (Supplementary Fig. 2e). These observations suggest that AG–LplA-based condensates are in a solid phase, showing similar characteristics to those previously reported in the field30,40,41.

Nuclear condensates for inducible regulation of CRISPR–Cas9 activity

After showing that NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA can be either transiently (Fig. 1b,g) or consistently targeted into the nucleus (Fig. 1d,e), we tested the capability of nuclear condensates to modulate target gene expression. One popular strategy of controlling gene expression inside the nucleus is CRISPRa, which capitalizes on a synthetic CRISPR-derived transactivator protein dCas9–VPR to modulate gene transcription in a gRNA-dependent manner42. Specifically, gRNA molecules designed to bind a target DNA sequence of interest recruit dCas9–VPR to various endogenous and transgenic expression units for site-specific transcriptional activation42. To engineer trigger-inducible CRISPR activity using synthetic condensates, we first used a canonical protein sequestration strategy and designed ANR-tagged dCas9–VPR (Supplementary Fig. 4a). In the absence of grazoprevir, dCas9–VPR–4×ANR would be sequestered into nuclear condensates (such as NLS–NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA), thereby prohibiting its accessibility to gRNA and the cellular transcriptional machinery. However, when we cotransfected constitutive expression vectors for dCas9–VPR–4×ANR, NLS–NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA and a reporter vector consisting of a minimal PhCMVmin promoter controlling the expression of human placental secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP), only a slight increase in SEAP expression was achieved upon grazoprevir treatment (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Thus, we speculated whether trigger-inducible sequestration of the gRNA molecule instead of the dCas9–VPR protein could result in improved regulation performance. For this purpose, we used a single gRNA (sgRNA) backbone engineered to contain MCP-specific MS2-box aptamer motifs in its tetraloop and stemloop domains (MS2sgRNA43). Then, we engineered a synthetic anchor protein NLS–MCP–2×ANR capable of binding MS2sgRNA and sequestering the respective gRNA molecules into ANR-specific NLS–NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA condensates, allowing the presence of grazoprevir to determine whether gRNA molecules shall reside within the inhibitory condensate or to interact with free dCas9–VPR to activate SEAP transcription (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Although this design led to a marginal improvement of grazoprevir-inducible SEAP expression, induction folds between basal expression and grazoprevir-regulated expression remained below twofold, thus necessitating further optimization (Supplementary Fig. 4a). However, when we combined both strategies and used dCas9–VPR–4×ANR and NLS–MCP–2×ANR as a ‘dual anchor’ to sequester MCP-specific gRNAs in the off state (Fig. 2a), grazoprevir-inducible transcriptional activation finally increased to exceed twofold (Supplementary Fig. 4a).

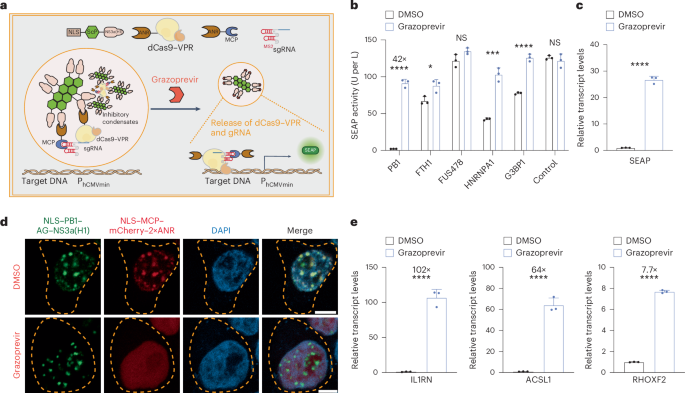

a, Inducible CRISPRa based on grazoprevir-repressible condensate formation. In the absence of grazoprevir, nuclear-localized condensates (NLS–ScP–NS3a) and ANR-containing anchors (NLS–ANR–MCP and ANR–dCas9–VPR) are designed to trap MS2-box containing gRNAs and inhibit transcriptional activation from gRNA-specific promoters. Grazoprevir releases the anchor(s) from the inhibitory condensate and activates transcription. b, Grazoprevir-repressible retention of gRNA and dCas9–VPR. HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with a minimal promoter (PhCMVmin)-driven SEAP expression vector (pWS107) and constitutive expression vectors for dCas9–VPR–4×ANR (pYK237), a PhCMVmin-specific gRNA containing MS2-box motifs (pWS137), a gRNA anchor (NLS–MCP–mCherry–2×ANR; pYK231) and synthetic ANR-specific nuclear condensates with NS3a(H1) fused to different scaffold proteins (FTH1, pYK194; HNRNPA1, pYK211; PB1, pYK164; FUS478, pYK209; G3BP1, pYK213; control, NLS–NS3a(H1)–AG, pYK325). SEAP expression in culture supernatants was profiled at 36 h after cultivation in cell culture medium containing 1 µM grazoprevir or DMSO (vehicle control). c, RT–qPCR quantification of SEAP activation (PB1 group). Transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH. d, Visualization of grazoprevir-triggered protein unloading from PB1-based condensates. HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with constitutive expression vectors for nuclear-localized condensates (NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1), pYK164; green) and an MS2-box-specific anchor (NLS–MCP–mCherry–2×ANR, pYK231; red) treated with 1 µM grazoprevir or DMSO. DAPI staining and confocal imaging (scale bar, 5 µm) were profiled at 24 h after transfection. The yellow dashed lines indicate cell membranes. e, Grazoprevir-dependent transcriptional activation of endogenous genes. HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with constitutive expression vectors for NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) (pYK164), dCas9–VPR–4×ANR (pYK237), NLS–MCP–mCherry–2×ANR (pYK231) and MS2-box-containing gRNAs specific for endogenous IL1RN (pSZ92 and pSZ93), ASCL1 (pSZ83 and pSZ84) or RHOXF2 (pSZ105 and pSZ106) genes. Then, 36 h after cultivation in cell culture medium containing 1 µM grazoprevir or DMSO (vehicle control), relative expression levels were profiled by RT–qPCR using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 2 and normalized to GAPDH. All data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed using two-sided t-tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001; NS, not significant. Filled circles show individual results. Numbers above the bars represent the fold change between datasets.

Source data

Next, we wondered whether CRISPRa performance could be improved by exchanging LplA into other proteins known to form biomolecular condensates in mammalian cells. Hence, we tested the PB1 domain of p62 protein30,38, N-terminal fragment of human FUS protein (FUS478)8,21,44, guanosine triphosphatase-activating protein SH3 domain-binding protein 1 (G3BP1)45, heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (HNRNPA1)46) and ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1)47 as potential candidates. In particular, each protein was individually fused to AG to produce the core scaffolding protein domain (ScP) of different nuclear-localized condensate structures (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2f). When we tested the capability of each condensate to regulate SEAP transcription through grazoprevir-repressible sequestration of both MS2sgRNA and dCas9–VPR–4×ANR, NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) revealed excellent regulatory performance, showing almost no basal SEAP expression and more than 40-fold induction triggered by grazoprevir (Fig. 2b). The superiority of PB1-based condensates over other counterpart constructs in modulating CRISPRa activity was also manifested throughout all previously described regulation strategies determined with the SEAP reporter assay (Supplementary Fig. 4b,c) or after quantitative analysis of corresponding transcript levels using reverse transcription (RT)–qPCR (Fig. 2c). FRAP experiments also suggested that PB1-based condensates may be a solid phase that may block the recruited client proteins (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Notably, regulation of transgene expression using NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) compared favorably to our experimental implementations of state-of-the-art CRISPRa strategies based on split reconstitution of dCas9 and VPR domains36, assembly of a sorting and assembly machinery complex43 or drug-inhibited self-cleavage48,49 (Extended Data Fig. 1). To visualize NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1)-mediated sequestration, we confirmed that, while condensate formation within the nucleus (indicated by AG-based green fluorescence) remained unaffected by grazoprevir, colocalization of mCherry-tagged NLS–MCP–2×ANR with condensate signals indicative for gRNA activity followed strict grazoprevir-repressible patterns (Fig. 2d). Lastly, we showed that NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1), dCas9–VPR–4×ANR and MS2sgRNA also allowed grazoprevir to efficiently upregulate various endogenous genes, such as interleukin 1 receptor antagonist (IL1RN), achaete-scute homolog 1 (ASCL1) and Rhox homeobox family member 2 (RHOXF2) (Fig. 2e), thus establishing synthetic nuclear condensates as a versatile strategy to control CRISPR–Cas9 activities in mammalian cells.

Transcriptional regulation by nuclear condensates

Modulation of transcriptional activation is another well-established route to control mammalian gene expression inside the nucleus8. To achieve stimulus-responsive transcription, one canonical strategy requires meticulous redesign of target promoter regions followed by engineering of site-specific transcription factors (for example, mammalian transactivators) programmed to exclusively bind such synthetic promoter regions with user-defined DNA-binding capability and/or effector functions16. However, the efficiency of such approaches (for example, the success rate of ‘converting’ different constitutive promoters into inducible elements) remains unpredictable, thus precluding ‘true’ modularity and large-scale development of gene switch designs14. Although CRISPRa and CRISPR interference strategies were developed to elegantly circumvent such limitation by allowing a same dCas9-based transcription factor to target and control various gRNA-specific DNA sites of interest42 (Extended Data Fig. 1), we wondered whether inducible control over specific transcription units could also be achieved in other standardized and CRISPR-independent manners. For example, DNA targeting may also be achieved by custom-designed anchor proteins consisting of a DNA-binding domain (DBD) and a tethering domain for an NS3a(H1)-containing inhibitory nuclear condensate (Fig. 3a). Thus, whether an ANR-based or GNCR-based anchor protein is selected, gene expression from any constitutive transcription unit can be systematically modulated through grazoprevir-triggered release or sequestration of anchor-specific DNA elements, respectively (Fig. 3a). When we tested the efficiency of different scaffold proteins to form inhibitory nuclear condensates, NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) again showed the best regulation performance in enabling grazoprevir-inducible gene expression used in combination with ANR-based anchor proteins (Supplementary Fig. 5a,b). Anchor proteins could comprise either the tetO-specific TetR protein37 (Supplementary Fig. 5a) or a custom-designed zinc-finger protein 1 from synZiFTRs4 as the DBD (Supplementary Fig. 5b), indicating the potential of using this strategy to regulate various write-protected or designable target loci of interest, respectively. In both configurations, we show that constitutive PhCMV-driven gene expression was effectively silenced and rendered responsive to grazoprevir through a specific set of NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) and ANR-based anchor proteins (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6c) and that the presence of anchor proteins alone had no negative impact on overall gene expression efficiency of each transcription unit (Supplementary Fig. 5c,d). Time-lapse imaging showed that PB1-based condensates allow a fast release of anchor proteins upon exposure to grazoprevir (Supplementary Fig. 6a). The strategy of using NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) to regulate TetR-specific and ZFP1-specific gene transcription also compared favorably to experimental setups using a same set of anchor proteins to recruit an NS3a(H1)-tagged KRAB domain used for state-of-the-art transcriptional silencing strategies50,51 (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, both episomal (Fig. 3b,c) and endogenous target genes could be specifically regulated in a grazoprevir-inducible (mediated by ANR-based anchors; Extended Data Fig. 2a) and grazoprevir-repressible manner (mediated by GNCR-based anchors; Extended Data Fig. 2b), thus confirming the applicability of synthetic nuclear condensates for on-demand silencing and activation in mammalian cells showing competitive advantages over conventional transcription factor-mediated approaches.

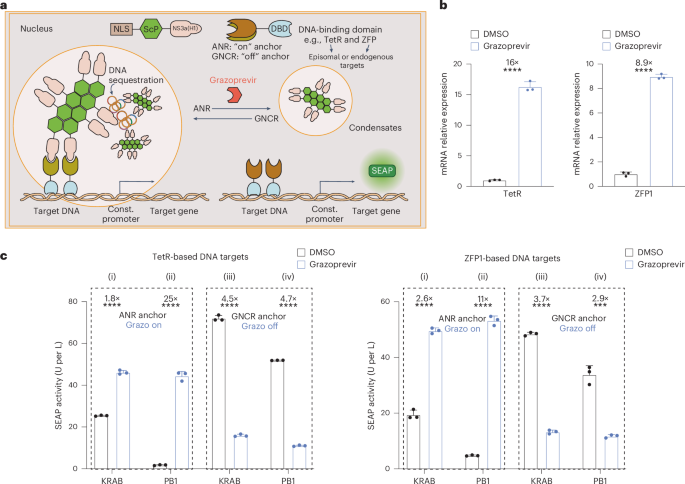

a, Schematics of transcriptional regulation by synthetic condensates. In the absence of grazoprevir, gene expression from episomal or genomic DNA is inhibited by ANR-mediated recruitment of NS3a(H1)-containing condensates to DBD-specific constitutive promoter regions. Grazoprevir disrupts the binding of ANR to NS3a(H1) and activates transcription by alleviating condensate-mediated steric hindrance. Using anchor proteins with ANR domains replaced by GNCR allows for grazoprevir-repressible gene expression. b, Grazoprevir-dependent derepression of SEAP transcription. Left, HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with a constitutive SEAP expression vector containing 14 TetR-specific tetO sites upstream of the constitutive PhCMV promoter (pYK262) and expression vectors for a TetR-based DNA anchor (NLS–TetR–3×ANR, pYK250) and nuclear condensate (NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1), pYK164). Right, HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with a constitutive SEAP expression vector containing eight ZFP1-specific binding sites upstream of PhCMV (pYK479) and expression vectors for NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) and ZFP1–NLS–4×ANR (pYK164 and pYK521). Relative SEAP expression in cells cultivated in 1 µM grazoprevir or DMSO was profiled by RT–qPCR at 24 h after transfection. Transcript levels were normalized to GAPDH. c, On-demand derepression and silencing of episomal genes. Left, TetR-based systems. Cells cotransfected with SEAP reporter (pYK262) and (i) NLS–KRAB–NS3a(H1) (pYK582) and NLS–TetR–3×ANR (pYK250), (ii) NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) (pYK164) and NLS–TetR–3×ANR (pYK250), (iii) NLS–KRAB–NS3a(H1) (pYK582) and GNCR–NLS–TetR (pYK648) and (iv) NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) (pYK164) and GNCR–NLS–TetR (pYK648). Right, ZFP1-based systems. Cells cotransfected with SEAP reporter (pYK479) and (i) NLS–KRAB–NS3a(H1) (pYK582) and ZFP1–NLS–4×ANR (pYK521), (ii) NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) (pYK164) and ZFP1–NLS–4×ANR (pYK521), (iii) NLS–KRAB–NS3a(H1) (pYK582) and GNCR–ZFP1–NLS (pYK650) and (iv) NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) (pYK164) and GNCR–ZFP1–NLS (pYK650). SEAP expression in culture supernatants was profiled after 24 h treatment with 1 µM grazoprevir or DMSO. All data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 3 independent experiments (b,c). Statistical significance was assessed using two-sided t-tests. ***P < 0.001 and ****P < 0.0001. Filled circles show individual results. Numbers above the bars represent the fold change between datasets.

Source data

Translational regulation by cytosolic and nuclear condensates

In recent years, the versatility and design flexibility of RNA-based gene switches have rendered translational regulation systems a central target of engineering52,53. Intuitively, translational regulation is achieved within the cytosol, for example, allowing the presence or absence of site-specific RNA-binding proteins to monitor ribosomal access of target gene mRNA and the onset of translational initiation54,55 (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Indeed, such strategies have also been successfully implemented with synthetic condensates engineered to reversibly sequester target gene mRNA31 or proteins18,30,32 into cytosolic microcompartments for the sake of realizing trigger-inducible gene expression in mammalian cells (Fig. 4a). Here, we confirm that LplA-containing condensates (NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA) show a clear advantage in regulating the translation of SEAP mRNA when directly compared to other condensate candidates containing different AG-containing scaffold proteins (Supplementary Fig. 7b), that the presence of a specific anchor protein MCP–2×ANR constantly binding to MCP-specific mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 8a) does not interfere with overall translation efficiency (Supplementary Fig. 7c) and that colocalization of cytosolic condensates and MCP-specific mRNA indeed follows grazoprevir-repressible patterns (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 7d). However, we speculated whether conditional retention of target mRNA within the nucleus (for example, into nuclear condensates) could be a more effective approach for translational regulation. Indeed, mRNA is inherently synthesized within the nucleus and only transported into the cytosol during maturation56. Thus, sequestration of ‘premature’ mRNA within engineered subcompartments inside the nucleus would provide important additional control layer(s) (that is, physical segregation and maturation control) when directly compared to conventional strategies that primarily focus on molecular or steric segregations within the cytosol. When we tested this hypothesis, nuclear condensates containing LplA, HNRNPA1 and FUS478 all provided efficient grazoprevir-inducible translational regulation of MCP–2×ANR-specific SEAP mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 7e), with NLS–FUS478–AG–NS3a(H1) accounting for the highest fold changes observed upon grazoprevir stimulation (Supplementary Figs. 7f and 8a) and showing characteristics of solid-state condensates (Supplementary Figs. 1c and 3). An almost complete retention of target gene mRNA inside nuclear condensates during basal grazoprevir-free conditions was further confirmed using confocal microscopy combined with single-molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 7g), thus confirming the conceptual design, as illustrated in Fig. 4a. Interestingly, although NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA-based cytosolic condensates appeared to account for a higher ratio between sequestered and released amounts of target mRNA (Fig. 4d), NLS–FUS478–AG–NS3a(H1)-based nuclear condensates provided markedly reduced basal gene expression levels and higher fold changes of grazoprevir-inducible mRNA translation in subsequent studies involving dose dependence (Extended Data Fig. 3a) and time-course analysis (Extended Data Fig. 3b). Importantly, we show that regulation of SEAP expression through condensate-mediated mRNA sequestration (Fig. 4d) occurred at equal transcript levels to confirm the proposed post-transcriptional regulation scheme (Supplementary Fig. 7h) and that retention of target gene mRNA within the nucleus is indeed a plausible control strategy for translational regulation (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Meanwhile, for FUS478-based condensates, we demonstrated that anchor proteins can be rapidly released upon grazoprevir addition (Supplementary Fig. 6b,d) and that the translational gene switch was fully reversible by repeated stimulation using low concentrations of 50 nM grazoprevir (Extended Data Fig. 3c). By custom-designing MCP-specific anchor proteins with ANR domains exchanged into GNCR-specific (Supplementary Fig. 8b,c) and MCP-specific (Supplementary Fig. 8d) target mRNA, the mRNA sequestration strategy by cytosolic and nuclear condensates could also be adopted to achieve translational regulation showing grazoprevir-repressible gene switch characteristics (Supplementary Figs. 7h and 8d,e), thereby corroborating the potential of using engineered biomolecular condensates as a rational, versatile and flexible gene regulation strategy in mammalian cells.

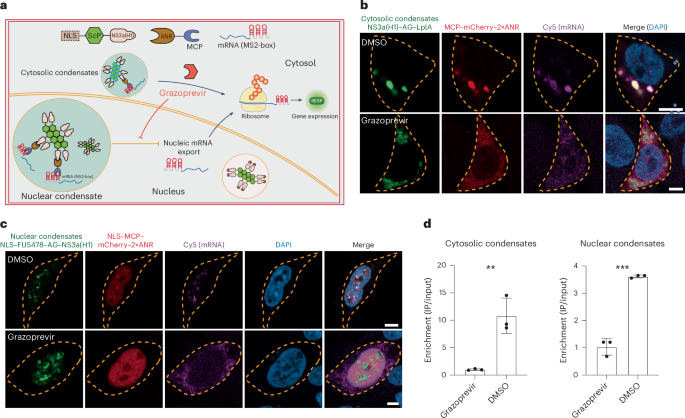

a, Schematics of translational regulation by synthetic condensates. In the absence of grazoprevir, target gene mRNA is trapped within nuclear or cytosolic condensates through constitutive NS3a(H1)–ANR and MCP–MS2-box interactions. Grazoprevir disrupts the binding of ANR to NS3a and enables mRNA translation. b,c, Visualization of grazoprevir-repressible mRNA trapping. Cytosolic LplA-based condensates (b): HEK-293 cells cotransfected with SEAP reporter mRNA (pYK63), NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA (pYK91, green) and MCP–mCherry–2×ANR (pYK225, red). Nuclear FUS478-based condensates (c): cells cotransfected with SEAP reporter mRNA (pYK63), NLS–FUS478–AG–NS3a(H1) (pYK209, green) and NLS–MCP–mCherry–2×ANR (pYK231, red). In b and c, cells were treated with 1 µM grazoprevir or DMSO (control). At 48 h after transfection, DAPI staining, Cy5 labeling of SEAP mRNA and confocal imaging were performed. Yellow dashed lines mark cell membranes (scale bar, 5 µm). Images are representative of three independent experiments. d, Quantification of grazoprevir-dependent mRNA binding by RIP. HEK-293 cells were cotransfected with SEAP reporter mRNA (pYK63) and either nuclear (NLS–FUS478–AG–NS3aH1–3×FLAG, pYK405; NLS–MCP–2×ANR, pYK218) or cytosolic (3×FLAG–NS3a(H1)–AG–LplA, pYK407; MCP–2×ANR, pYK195) condensates. RNA was extracted and coimmunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG affinity gel at 48 h after transfection. SEAP levels were quantified by RT–qPCR (input versus output). All data are shown as the mean ± s.d. of n = 3 independent experiments. Statistical significance was assessed using two-sided t-tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001. Filled circles show individual results.

Source data

Discussion

Membraneless organelles have rapidly ascended to become a focal point in both cell biology and synthetic biology, with several groundbreaking studies underscoring the vast potential of such genetically encoded, protein-based entities57. For example, naturally occurring P granules58 or stress granules45,59 emerge through spontaneous condensation and phase separation, thereby contributing to cellular organization and spatiotemporal regulation of diverse biological functions. Specifically, these condensates were evolved to concentrate proteins and nucleic acids within micron-scale structures that are essential for the regulation of RNA metabolism, ribosome biogenesis, DNA damage response and signal transduction17. In recent years, the robust, dynamic and ‘designable’ segregation properties of such biomolecular condensates have also gained increased attention in various engineering-driven disciplines such as synthetic biology and biotechnology. For example, genetically encoded condensates were elegantly repurposed as synthetic oligomeric scaffold domains for the concentration of transcription factors to amplify gene expression8. Furthermore, biomolecular condensates engineered to sequester and release plasmid DNA were introduced into bacteria to allow assembly of transcriptionally active ‘nucleus-like’ structures in prokaryotes60. However, the use of engineered condensates as an ordinary strategy for gene expression control is still in its infancy. Although effective control over protein activity and translation was achieved through regulated sequestration and release of target proteins and RNA molecules in the cytosol of mammalian cells18,30,31,32,33, custom-designed synthetic condensates with the capability to regulate various endogenous and ectopic gene products inside the nucleus would greatly broaden the utility range of such genetically encoded microstructures.

Here, we show that solid-state protein condensates can be tethered to various subcellular sites of interest (that is, cytosol, nucleus, plasma membrane and mitochondria) to regulate a wide variety of gene expression loci, including trigger-inducible regulation of translation and transcriptional activation and silencing of both endogenous and ectopic genes. While the majority of translational regulation strategies adhere to a conventional mindset of using any available method to isolate target mRNA from the ribosomal machinery in the cytosol, we show that conditional sequestration of its corresponding pre-mRNA form within nuclear condensates offers an attractive and effective alternative. This result is not too surprising in retrospect because pre-mRNA molecules retained inside the nucleus are already translationally inactive by design and introducing an additional microcompartment within the nucleus in the form of synthetic condensates would markedly increase the physical protection barrier(s) between the translationally off (mRNA stored inside nuclear condensates) and on states (grazoprevir-inhibited retention). In fact, when directly comparing the performance of mRNA sequestration between cytosolic and nuclear condensates (Fig. 4), FUS478-based nuclear condensates permitted largely reduced basal gene expression than LplA-based cytosolic condensates (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b) although grazoprevir triggered the release of larger RNA amounts from LplA-based condensates (Fig. 4d). Furthermore, we could indeed visualize a substantial amount of mRNA ‘leaking’ out of the cytosolic condensates in the absence of grazoprevir (Fig. 4b), whereas no cytosolic mRNA was recorded under same conditions with nuclear condensates (Fig. 4c). Notably, translational regulation by nuclear mRNA retention appeared to specifically require the action of condensate structures, as only recruitment of mRNA-binding proteins into the nucleus showed insufficient regulation efficacy in direct comparison (Supplementary Fig. 7a).

Traditional CRISPR–Cas9 technologies often focus on controlling either the Cas9 protein or the sgRNA separately (Supplementary Fig. 4a). This conventional approach, while effective in specific context, can fail to fully harness the potential of CRISPR technology, particularly in more complex gene regulation scenarios that demand coordinated control over multiple genetic elements. In contrast, the condensate-based dual anchor strategy described in this study proved advantageous for manipulation of both protein and nucleic acid elements using a singular system, ultimately permitting over 40-fold gene switch efficiency when regulating transgenes and even up to 102-fold when regulating certain endogenous targets (Fig. 2b,e). Different efficiencies of CRISPRa may result from different efficacies of sgRNA design or differences in the chromatin state surrounding the target promoter region43,61. For transcriptional regulation, on-demand recruitment of specific epigenetic effector domains, such as KRAB from human Kox1, may be regarded as a current design standard42,62. Here, we show that, while synthetic nuclear condensates and KRAB domains show similar repression efficiencies, NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) had notable advantages when establishing trigger-inducible tethering systems, demonstrating good compatibility with grazoprevir-regulated ANR and GNCR elements, as well as various endogenous or synthetic transcription units (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 5 and Extended Data Fig. 2). The capability by NLS–PB1–AG–NS3a(H1) of regulating genomic targets may be surprising to a certain extent because it should not be expected that entire chromosomes would be trapped within nuclear condensates in such contexts. Thus, the molecular mechanism of transcriptional regulation by condensate-mediated approaches might remain a question for future investigation.

Collectively, we demonstrate a holistic, modular and versatile design principle that could establish biomolecular condensates as an effective and pragmatic alternative to regulate target gene expression in mammalian cells. At present, when designing gene switches operating at different intracellular stages of protein expression, regulatory relationships must often be carefully redesigned or readjusted when toggling between combinations of input signals and target genes. To engineer different inducible promoters responding to different transcription factors, for example, specific binding sites inserted into synthetic promoter regions must be individually replaced, often resulting in unpredictable functional outcome, cell-type-specific performance and overall engineering labor. In contrast, the ‘top-down’ approach of using synthetic condensates first targets any endogenous or synthetic gene locus of interest through custom-designed anchor proteins, which subsequently tether or untether a same inhibitory condensate structure through preprogrammed protein–protein interactions. Here, we used the well-established grazoprevir-controlled triad GNCR–NS3a(H1)–ANR to achieve trigger-inducible condensate recruitment or target gene product release. Exchange of this conditional protein dimerization module with other pairs of ligand-dependent protein–protein interactions63 would enable other input signals to control the same target genes in a highly modular and plug-and-play manner. In terms of target genes, we show that recruitment of synthetic condensates could effectively silence the strong constitutive PhCMV promoter without the need to insert specific binding sites between promoter and coding gene regions (Fig. 3). As long as an anchor protein is designed to target a noncoding region anywhere close or distal to an expression unit of interest, trigger-inducible or trigger-repressible silencing of either endogenous or ectopic genes can be effectively achieved upon condensate recruitment (Fig. 3b). In other words, inducible transcriptional activation can be readily achieved using constitutive expression units, which could avoid excessive and painstaking redesign of episomal vectors when constructing regulated expression systems. In theory, targeting and silencing of endogenous RNA products using our condensate-based strategy would also be technically feasible, for example, using RCas9 as an integral anchor protein domain and following a similar design of a dCas9-centered strategy (Fig. 2a). However, we believe that such engineered approaches would not have notable benefits over conventional knockdown strategies because the regulated expression of RNA interference or antisense RNA componentry is expected to yield satisfactory outcomes. Overall, gene expression control by synthetic condensates is believed to provide an alternative mindset that could pave the way to numerous future applications in biotechnology and synthetic biology.

Methods

Vector design

Construction details and references for all expression vectors are provided in Supplementary Table 1. New plasmids were generated using standard restriction and digestion cloning (New England Biolabs) or Gibson assembly techniques (Seamless cloning kit; Beyotime Biotechnology, D7010M) and verified by Sanger sequencing (Tsingke Biotechnology). Signal peptides fused to dCas9–VPR (Addgene plasmid 63798) were kindly provided by G. Church. EGFP (Addgene plasmid 54759) was kindly provided by M. Davidson. PCMV–EGFP–LplA was kindly provided by P. Yang.

Cell culture and transfection

Human embryonic kidney cells (HEK-293T; American Type Culture Collection, CRL-3216) were cultivated in DMEM standard medium (Bio-Channel Biotechnology, BC-M-005) supplemented with 10% v/v FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 10099141, lot 2177370) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin solution (Beyotime Biotechnology, ST488) under a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37 °C. For cell passaging, cells of preconfluent cultures were detached by incubation in 0.05% trypsin–EDTA (Sangon Biotech, A610629-0050, lot F319BA0030) for 3 min at 37 °C, collected in 10 ml of cell culture medium, centrifuged at 200g for 2 min and resuspended in fresh culture medium at 105 cells per ml before seeding into new tissue culture plates. Cell number and viability were quantified using an Invitrogen Countess II AMQAX1000 Cell Counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Unless indicated otherwise, transfection was performed at 24 h after seeding 5 × 104 mammalian cells into each well of a 24-well plate (Labselect, 11312). Transfection was performed using a polyethylenimine (PEI)-based protocol at a PEI:DNA ratio of 5:1 (w/w) and in a transfection volume of 50 µl of native serum-free DMEM per well. Then, 15 min after incubation at room temperature, the transfection mixture was added dropwise to the cells, which were then incubated for 6 h followed by medium exchange for PEI removal or addition of trigger compounds (grazoprevir). Cells were further cultivated for another 24–48 h before analytical assays.

RT–qPCR

Total RNA of cells was isolated using the Quick-RNA Microprep kit (Zymo Research, R1051) and reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA using the HiScript II QRT SuperMix kit (Vazyme Biotech, R233-01). For quantitative analysis, PCR was carried out with an initial step of 95 °C for 30 s followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s on the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 1 real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using the ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR master mix (Vazyme Biotech, Q711-02) and primers listed in Supplementary Table 2.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

At 2 days after transfection, cells were detached using trypsin–EDTA and resuspended in fresh cell culture medium, followed by centrifugation at 8,000g for 30 s. After supernatant removal, cells were lysed by incubation in 1 ml of ice-cold NETN300 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.05% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF and 50 U per ml of murine RNase inhibitor) for 15 min and centrifuged for another 30 min at 16,000g and 4 °C. Then, 200 ml of supernatant was collected and mixed with 1 ml of TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15596026) for RNA purification (input sample), while the remaining supernatant was diluted in NETN0 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 0.05% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF and 50 U per ml of murine RNase inhibitor) in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio and immunoprecipitated through incubation with anti-FLAG affinity gel (Beyotime Biotechnology, P2271) for 90 min at 4 °C. The affinity gel was then centrifuged at 8,000g for 30 s to remove supernatants and washed four times in ice-cold NETN300 wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 0.05% Triton X-100 and 1 mM PMSF) supplemented with or without 1 µM grazoprevir or DMSO (vehicle control). Finally, the gels were mixed with 1 ml of TRIzol reagent for RNA purification to produce the output sample. Total RNA amounts in input and output samples were further quantified by RT–qPCR analysis.

Analytical assays

SEAP assay

Heat-inactivated (30 min, 65 °C) cell culture supernatants (80 μl) were transferred into a 96-well plate and mixed with 100 μl of 2× SEAP buffer and 20 μl of SEAP substrate solution containing 20 mM para-nitrophenyl phosphate. Time-course of SEAP activity was recorded by monitoring the absorbance of samples at 415 nm using the Multiskan Sky microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, A51119700C) at 37 °C with Skanlt software for microplate readers (versions 6.0.2.3 and 5.0.0.42).

Confocal microscopy

For fixed cell imaging, 2 × 104 HEK-293T cells were seeded on Fisherbrand microscope cover glasses (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 12-545-80) precoated with 5 mg ml−1 poly(d-lysine) (Beyotime Biotechnology, C0312). Then, 24 h after transfection and chemical stimulation, the culture medium was discarded and cells were gently washed with 1 ml of Gibco PBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C10010500BT) before incubation in 1 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution (Beyotime Biotechnology, P0099) for 10 min. For mitochondrial imaging, cells were preincubated in medium supplemented with 250 nM MitoTracker deep red FM (Yeasen Biotechnology, 40743ES50) for 30 min at 37 °C. After fixation, PFA-treated cells were washed with PBS, followed by permeabilization using immunostaining permeabilization solution containing Triton X-100 (Beyotime Biotechnology, P0096) for 10 min. After three PBS washes, cells were mounted onto microscope slides and incubated in ProLong Diamond antifade mounting with DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, P36966) at room temperature in the dark for 24 h. Imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM 980 Airyscan confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy) using a ×63 objective lens and excitation spectral laser lines set at 405 nm (DAPI), 488 nm (EGFP/AG), 594 nm (mCherry) or 640 nm (Cy5 and MitoTracker).

For live-cell imaging, 1 × 105 HEK-293T cells were seeded on a 20-mm confocal dish (Wuxi NEST Biotechnology, 801001) precoated with 5 mg ml−1 poly(d-lysine). Then, 24 h after transfection, cells were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 980. For FRAP experiments, bleaching was performed using a 488-nm laser operating at 80% laser power. Fluorescence images were acquired using the ZEN 2.3 system.

Image analysis

Condensate formation capability was estimated through the total fluorescence within the thresholded fraction (area × mean background-subtracted fluorescence) divided by the total fluorescence (area × mean background-subtracted fluorescence) for each cell. The fraction of scaffold protein within the client protein was determined by the fluorescence of the scaffold protein overlapping with the thresholded client protein area divided by the total fluorescence of the scaffold protein for each cell. Images were processed using ImageJ or FIJI software.

Single-molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH)

First, 48 h after transfection and cultivation on coverslips precoated with poly(d-lysine), cells were rinsed with PBS and then fixed with 4% PFA solution for 10 min, followed by a 5-min washing step (twice in PBS) and incubation in 70% ethanol for 1 h at 4 °C. Next, cells were exposed to freshly prepared FISH wash buffer composed of 10% formamide and 2× SSC for 5 min before the coverslips were hybridized at 37 °C for 16 h with FISH hybridization buffer supplemented with 250 nM of custom-designed oligonucleotide probes. After hybridization, the coverslips were washed twice with 37 °C FISH wash buffer for 30 min and then with nuclease-free 2× SSC for 5 min. Finally, coverslips were mounted onto slides, exposed to ProLong Diamond antifade mounting containing DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific, P36966) and incubated at room temperature for 24 h for confocal microscopy. Oligonucleotide probes were designed using the Stellaris probe designer tool by LGC Biosearch Technologies and purchased from Tsingke Biotechnology. Sequences of all probes are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Data analysis

Two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests were used to evaluate the statistical significance of differences between two groups. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses