PTEN loss drives p53 LOH and immune evasion in a novel urothelial organoid model harboring p53 missense mutations

Introduction

Bladder cancer was the tenth most prevalent cancer globally in 2020, with 573,000 new cases and 213,000 deaths [1, 2]. Most bladder cancer cases are pathologically classified as urothelial carcinomas, categorized as the non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) or muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) type. MIBC comprises about 25% of bladder cancer cases, with regionally invasive disease and metastatic disease patients having 50% and 15% 5-year survival rates, respectively [3]. Unfortunately, the prognosis of MIBC patients has not significantly improved over recent decades. While immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting programmed cell death 1 (PD-1)/programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) have been approved for advanced bladder cancer, their response rate is limited to 20–30% of patients [4]. Because of this, there are urgent needs to identify factors that can define response/failure and to establish novel combination therapies that can enhance the efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies. However, an incomplete understanding of bladder carcinogenesis and its associated immune evasion mechanisms is the greatest barrier for these efforts [5]. Therefore, reliable syngeneic models for researching bladder cancer tumorigenesis mechanisms and the tumor immune microenvironment are required [6].

In bladder cancer, p53 mutations are the most prevalent, with over 60% being missense mutations [7]. Despite this, no de novo carcinogenesis bladder cancer mouse models involving a p53 missense mutation have been reported, whereas p53 knockout models have been documented [8, 9]. In addition to p53 and the cell cycle, RTK-RAS-PI3K pathway and epigenetics-related gene mutations are relevant in human MIBC [7]. PTEN copy number loss is common in MIBC and is linked to reduced RNA expression levels [10]. Indeed, several reports have shown that dual knockout of Trp53 and Pten conferred tumorigenic ability to mouse bladder cells [8, 9, 11]. However, reports on the causal relationship between mutations in epigenetic-related genes, such as KMT2C, and urothelial carcinogenesis are extremely limited [12] compared with reports on mutation frequencies [7, 13]. Hence, we became interested in whether the additional loss of Pten and/or Kmt2c in the context of a Trp53 missense mutation could support bladder carcinogenesis.

Previous studies from our group and others have demonstrated that cytokeratin 5 (Krt5)-expressing urothelial cells can be the originating cell type of basal subtype MIBC [14, 15]. However, because Krt5-expressing cells exist throughout the body, it has been a challenge to induce mutations specifically in the urothelium. There have been only a few reports showing that intravesical injection of Adeno Krt5-Cre in flox mice or 4′-hydroxy-tamoxifen (4′-OHT) treatment of Krt5-CreERT2-expressing flox mice could enable Krt5+ cell-specific gene recombination and tumor growth [9]. One obstacle for intravesical vector injection is the barrier of the glycosaminoglycan layer, which prevents vector access to the Krt5-expressing basal layer [16]. Another problem is that systemic treatment with tamoxifen can induce mutations in Krt5-expressing cells throughout the whole body that results in premature mouse death because of tumor development. Krt5-expressing cells in multiple tissues have a period required for carcinogenesis that is shorter than that of the bladder [11].

In the present study, we addressed these hurdles by using an organoid culture system. Inducing in vivo gene recombination in donor mice enabled selective collection of Krt5-expressing cells of urothelial lineage for organoid culture. Gene editing using the CRISPR/Cas9 system is quite straightforward in organoids. After returning the gene-edited cells into the mice and evaluating their tumorigenicity, we could verify the contribution of these specific genes to carcinogenesis. Using this system, we demonstrate that cells of the Krt5-expressing urothelial lineage can recapitulate tumors with features of the human MIBC basal-squamous subtype via organoids. Additionally, the present study shows that loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of Trp53 is essential in the context of Trp53 missense mutations.

Results

Establishment of Trp53 mutant K5-mUrorganoids as a model of human bladder cancer that undergoes autonomous enrichment toward Trp53 mutant LOH during tumorigenesis

To investigate the common driver genes among human and murine MIBC, we performed WES using tumor tissues obtained from human MIBC (n = 10) and murine bladder cancer induced by N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl)-nitrosamine (BBN) (n = 6). In addition to recurrent p53 mutations (50% in human MIBC and 67% in mouse MIBC), we observed frequent mutations in genes involved in ASC-2/NCOA6 complex (ASCOM) [12] (Fig. S1). Among those, a KMT2C (Kmt2c) alteration was most common with 40% (4/10) of human MIBC tumors and 83% (5/6) of BBN-induced murine bladder cancer samples (Fig. S1), which were consistent with those in a previous report from TCGA [13]. Using these findings together with insights from a previously reported bladder cancer mouse model [8], we initially selected Kmt2c and Pten as additional target genes to generate a p53 missense mutation-based mouse model. Furthermore, we hypothesized that Krt5+ urothelial cells could be the cell of origin of basal subtype MIBC according to previous reports from our group and others [14, 15].

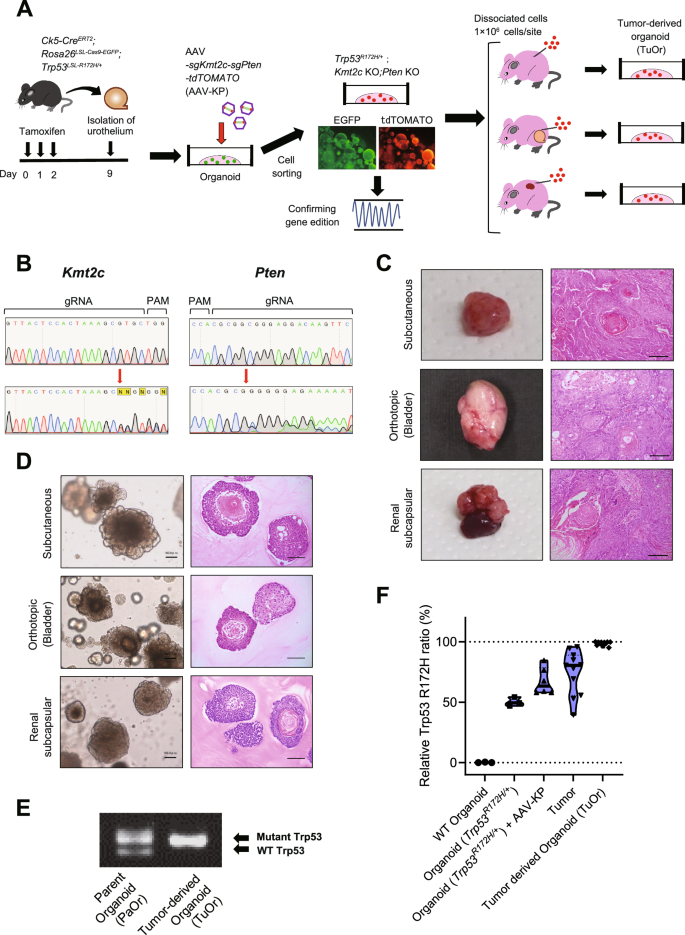

To establish a bladder cancer mouse model from these hypotheses, we used organoids derived from genetically engineered mice (GEM) (Fig. 1A). First, Krt5CreERT2/+; Rosa26LSL-Cas9-EGFP; Trp53LSL-R172H/+ mice were treated with tamoxifen for 3 days for Krt5-expressing cells, including basal and intermediate cells, in the bladder urothelium to express Cas9, R172H mutant p53, and EGFP. Seven days after tamoxifen treatment, we collected the urothelium and generated organoids (Trp53R172H/+ K5-mUrorganoids). The K5-mUrorganoid cells were sorted using GFP expression to aggregate only Krt5-lineage urothelial cells. These K5-mUrorganoids maintained expression of basal markers, such as Krt5 and p63 (Fig. S2). Next, cells were infected with AAV concomitantly expressing sgKmt2c and sgPten to induce gene editing using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sanger sequencing was used to confirm gene editing of the target regions (Fig. 1B). Trp53R172H/+; Kmt2c–KO; Pten KO K5-mUrorganoid cells led to tumor development in athymic mice (BALB/cAJcl-nu/nu) by subcutaneous, orthotopic, and renal subcapsular injections. The tumors demonstrated a similar histology to those of human MIBC tumors with squamous differentiation (Fig. 1C). We then generated organoids from these tumors (tumor-derived organoid; TuOr). TuOrs retained the histological characteristics of the tumors, including keratin pearl structures inside (Fig. 1D).

A Schematics of establishing K5-mUrorganoids. Genetically engineered mice with the indicated genotype were treated with tamoxifen orally for 3 consecutive days, and then the bladder urothelial cells were collected and subjected to 3D organoid culture (K5-mUrorganoid). CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing was performed using an adeno-associated virus (AAV) expressing single-guide (sg)RNA. K5-mUrorganoids were then subjected to ex vivo evaluation or to subcutaneous, orthotopic, and renal subcapsular inoculation for in vivo tumorigenicity assays. B Representative images of Sanger sequencing showing successful gene editing at the targeted positions (red arrows) by guide RNAs (gRNAs) for Kmt2c (left) and Pten (right). PAM, proto-spacer adjacent motif. C Representative macroscopic (left) and microscopic (right, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining) images of tumors derived from Trp53R172H/+; Kmt2c–KO; Pten KO K5-mUrorganoids inoculated in athymic mice at the indicated sites. Note that the tumors exhibit histological characteristics of human muscle-invasive bladder cancer (MIBC) with squamous differentiation. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. D Representative bright-field (left) and H&E (right) microscopic images of tumor-derived organoids (TuOrs). The TuOrs retained the histological phenotype, including keratin pearl structures. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. E Representative gel image of genomic PCR for Trp53 status in parent Trp53R172H/+; Kmt2c-KO; Pten KO K5-mUrorganoids (PaOr, left) and TuOrs (right). Note that the band for wild-type (WT) Trp53 was undetectable in TuOrs, whereas the band for mutant Trp53 was thickened. F Digital PCR results of WT organoids, organoids with Trp53R172H/+, organoids with Trp53R172H/+; Kmt2c KO; Pten KO, tumors, and TuOrs. See also Supplementary Figs. S1–S5.

Genotyping PCR revealed that TuOrs lost the WT Trp53 allele, but maintained the mutant allele, indicating LOH of Trp53 (Trp53R172H/LOH, Fig. 1E). Quantitative digital PCR showed that the Trp53 mutant allele ratio gradually increased during the tumorigenesis process and LOH cells were enriched in TuOrs (Figs. 1F and S3). Copy number analysis using WES suggested that these TuOrs had copy number loss LOH (copy number ratio: −0.5, Fig. S4A), whereas the others had a mixture of copy number neutral LOH [17] and copy number loss LOH (copy number ratio: −0.2 to −0.3, Fig. S4B). This suggested that loss of the WT Trp53 allele favors tumorigenesis for Trp53-mutated K5-mUrorganoid cells.

Next, to examine the functional significance of Kmt2c loss and Pten loss in the tumorigenicity of Trp53R172H/Δ (generated from Trp53LSL-R172H/flox mouse by Cre recombination) K5-mUrorganoids, we designed two distinct sgRNAs for Kmt2c and Pten. The genes were edited individually using an AAV expressing one of the sgRNAs or in combination with the two sgRNAs for Kmt2c and Pten. We also prepared Trp53R172H/LOH K5-mUrorganoids, which were enriched by treating Trp53R172H/+ K5-mUrorganoids with 5 μM nutlin-3, an inhibitor of murine double minute 2 (MDM2), which is the main upstream regulator of p53. After deletion of Kmt2c and/or Pten, the in vivo tumorigenicity of Trp53+/+, Trp53R172H/+, and Trp53R172H/LOH K5-mUrorganoids was assessed by subcutaneous inoculation in athymic mice (n = 3 or 4 for each genotype, Fig. S5A). Trp53 WT K5-mUrorganoids did not form any tumors, irrespective of the Kmt2c or Pten genotype (Fig. S5B/C). However, Trp53R172H/+ (9/16) and Trp53R172H/LOH (11/12) K5-mUrorganoids formed tumors only when Pten was deleted, but irrespective of Kmt2c deletion (Figs. S5B/C). Trp53 LOH changes (loss of the WT allele) were observed in 77.8% (7/9) of tumors derived from Trp53R172H/+ K5-mUrorganoids (Fig. S5D). On the contrary, Pten+/+ K5-mUrorganoids did not form any tumors, irrespective of the Trp53 or Kmt2c genotype (Fig. S5B). These results indicate that LOH of Trp53 and loss of Pten were strongly related to in vivo tumorigenesis in the context of Trp53-mutant K5-mUrorganoids, whereas loss of Kmt2c was not.

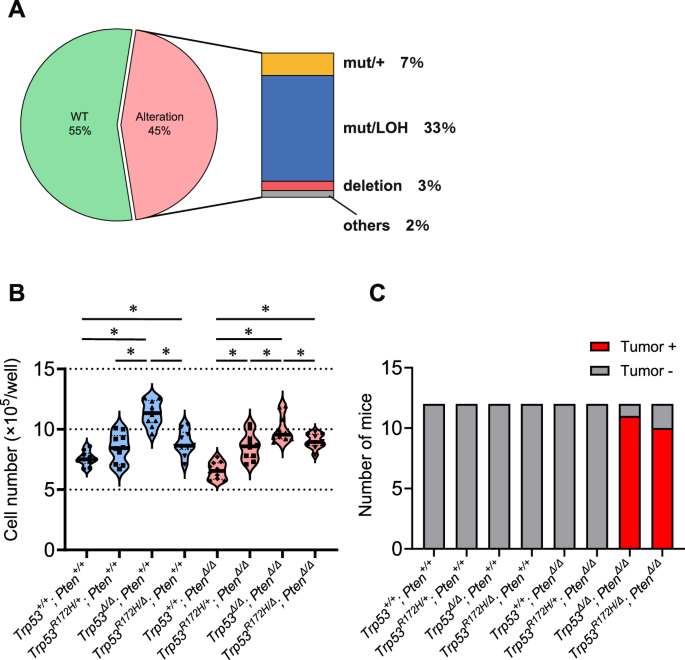

Single nucleotide alteration with loss of the WT allele is the most frequently observed pattern in p53-altered human MIBC

We then investigated the p53 status of human MIBC samples using TCGA data (Fig. S6A). TP53 was most frequently altered gene, being reported in 45% of the MIBC patients included. Of those, 74% (33% of overall cases) harbored single nucleotide alteration with LOH (Fig. 2A). We did not find any correlation between TP53 status and overall survival in the TCGA cohort (Fig. S6B), or with subtype, disease stage, or pathological T stage (Fig. S6C). Therefore, in cases with TP53 alteration, a missense mutation with LOH is the most common, suggesting that there is clinical relevance for examining the functional significance of p53 mutations with LOH in MIBC development.

A The proportion of patients according to the p53 gene status in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) data. B Ex vivo cell proliferation rate in organoids with distinct genotypes (n = 10). *P < 0.05. C In vivo tumor-forming rates in athymic mice for organoids with distinct genotypes (n = 12). See also Supplementary Figs. S6–S10.

Loss of the WT Trp53 allele and Pten loss confer in vivo tumorigenic ability to K5-mUrorganoids in athymic mice

To further interrogate the biological influence of the status of Trp53 and Pten on K5-mUrorganoid tumorigenicity, we generated eight distinct genotypes of K5-mUrorganoids by crossing Pten flox and Trp53 flox mice: Trp53 with WT (Trp53+/+), heterozygous mutant (Trp53R172H/+), homozygous deletion (Trp53flox/flox before recombination, Trp53Δ/Δ after recombination), and mutant LOH (Trp53R172H/flox before recombination, Trp53R172H/Δ after recombination) and Pten with WT (Pten+/+) and homozygous deletion (Ptenflox/flox before recombination, PtenΔ/Δ after recombination) (Fig. S7A–D). Then, we evaluated the ex vivo and in vivo phenotypes, as well as the gene expression and molecular pathway profiles using bulk RNA-seq.

Trp53Δ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids showed significantly higher ex vivo proliferation than any other genotype, whereas no significant differences were observed between Trp53R172H/+ and Trp53R172H/Δ (Fig. 2B). Pten status did not appear to impact the K5-mUrorganoid proliferation ability. For in vivo tumorigenicity, Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ (10/12) showed an equivalent subcutaneous tumor development rate as Trp53Δ/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ (11/12) in athymic mice, whereas the other K5-mUrorganoid genotypes, including Trp53R172H/Δ; Pten+/+ and Trp53R172H/+; PtenΔ/Δ, did not form any tumors (n = 12 for each genotype) (Fig. 2C). These results again indicate that loss of the WT Trp53 allele together with Pten loss is required for in vivo tumor formation in athymic mice. Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids had a similar tumorigenic potential as Trp53Δ/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ, despite a lower proliferation ability ex vivo.

To investigate the dynamics of LOH of Trp53 in the context of missense mutations, as well as the potential effect of Pten loss, we monitored the Trp53 status over the passages using digital PCR of Trp53R172H/+; Pten+/+ and Trp53R172H/+; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids. The relative ratio of the Trp53R172H allele did not change significantly over passage (from P8 to P13) in Trp53R172H/+; Pten+/+ K5-mUrorganoids (Fig. S8A), while it became dominant over passage (from P4 to P9) in Trp53R172H/+; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids (Fig. S8B). Trp53R172H/+; Pten+/+ K5-mUrorganoids (P11) did not form tumors in vivo, at least up to 8 weeks after inoculation (Fig. S8C, left), nor did Trp53R172H/+; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids (P5) (Fig. S8C, middle). After the eighth passage, however, Trp53R172H/+; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids acquired in vivo tumorigenicity (Fig. S8C, right).

The experimental results thus far indicate that, as ex vivo passage is repeated, loss of Pten can drive the LOH of the missense mutation allele of Trp53. A proliferation advantage and an accumulation of changes from passage stress do not seem to be major driving forces for LOH. For in vivo tumorigenesis, both loss of the WT allele of Trp53 and loss of Pten are required, suggesting that the contribution of Pten loss to in vivo tumorigenesis goes beyond promoting LOH of Trp53.

Because LOH was induced by P9 in Trp53R172H/+; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids, but not in Trp53R172H/+; Pten+/+ K5-mUrorganoids even up to P13, the difference in LOH induction between Trp53R172H/+; PtenΔ/Δ and Trp53R172H/+; Pten+/+ does not appear to be from changes accumulated with repeated passages. On the other hand, because the Trp53R172H/+; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids enriched Trp53 mutant LOH from P4 to P9, we considered that the accumulated changes through repeated passages, in addition to the loss of Pten, has not been fully eliminated as a contributor to the LOH changes in Trp53R172H/+ K5-mUrorganoids. In other words, whether there was a contribution from multiple passages besides Pten loss or not remained unclear at that moment. We hypothesized that Pten loss is able to induce Trp53 mutant LOH independent of multiple passages. Since cells expressing the wild-type p53 cannot survive in the presence of nutlin-3, an MDM2 inhibitor [18, 19], this means that cells proliferating under these conditions have lost the Trp53 wild-type allele (in the case of Trp53mut/+, Trp53 mutant LOH). The eight K5-mUrorganoid genotypes were cultured in the presence or absence of nutlin-3 without repeated passages. As anticipated, Trp53+/+; Pten+/+, Trp53+/+; Pten∆/∆, and Trp53R172H/+; Pten+/+ K5-Urorganoids scarcely formed organoids in the presence of nutlin-3. However, Trp53R172H/+; Pten∆/∆ K5-Urorganoids were able to grow in the presence of nutlin-3 at an approximately 50% rate compared with that in the absence of nutlin-3 (Fig. S9A/B).

K5-Urorganoids with the original Trp53R172H/+; Pten∆/∆ genotype that had grown in the presence of nutlin-3 showed p53 LOH (Trp53R172H/LOH, Fig. S9C) and acquired in vivo tumorigenic ability in athymic mouse (Fig. S9D). This was consistent with the Trp53R172H/LOH; Pten∆/∆ K5-Urorganoids generated from repeated passages. TuOrs were generated from each tumor developed from the Trp53R172H/+; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids with nutlin-3 selection. These TuOrs showed copy number neutral LOH of Trp53 by WES analysis (Fig. S9E). These results collectively indicate that Pten loss can promote LOH of Trp53 in the context of Trp53R172H/+.

We previously constructed four gene sets showing distinct enrichment patterns regarding human MIBC molecular subtypes using TCGA 2017 [13]. We also demonstrated that the gene expression profile of BBN-induced bladder cancer originating from Krt5-expressing mouse urothelial cells has the highest similarity to that of the human MIBC basal-squamous subtype [15]. Specifically, GSEA showed a characteristic enrichment pattern for the basal-squamous subtype, in which gene sets 3 and 4 were highly enriched, but gene sets 1 and 2 were not [15]. We performed GSEA using these four gene sets on tumors with each genotype and compared the results with those of normal mouse urothelium. Tumors from Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆, Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆, and Trp53R172H/LOH; Pten∆/∆ (from Trp53R172H/+; Pten∆/∆ with nutlin-3) K5-mUrorganoids were highly enriched in gene sets 3 (normalized enrichment score [NES]: 1.952–2.879) and 4 (NES: 2.647–2.811). These characteristics are specific to the basal-squamous subtype in TCGA 2017 (Fig. S10A/B). Tumors from Trp53R172H/LOH; Kmt2c-KO; Pten KO K5-mUrorganoids showed a relatively lower NES (1.185 for gene set 3 and 2.531 for gene set 4), which presumably reflects the cellular heterogeneity caused by the relatively random gene editing associated with the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Our results using GSEA are generally consistent with the histological findings of these tumors, which recapitulate human MIBC with squamous differentiation.

Collectively, our mouse bladder cancer model characterized by Trp53 LOH recapitulated both the histological and genetic characteristics of the human basal-squamous subtype, which has been shown to have the most unfavorable prognosis among MIBC patients [20]. This indicates that this model is a clinically relevant and experimentally useful tool for research aiming for a better understanding of the bladder carcinogenesis process to ultimately address clinically unmet needs.

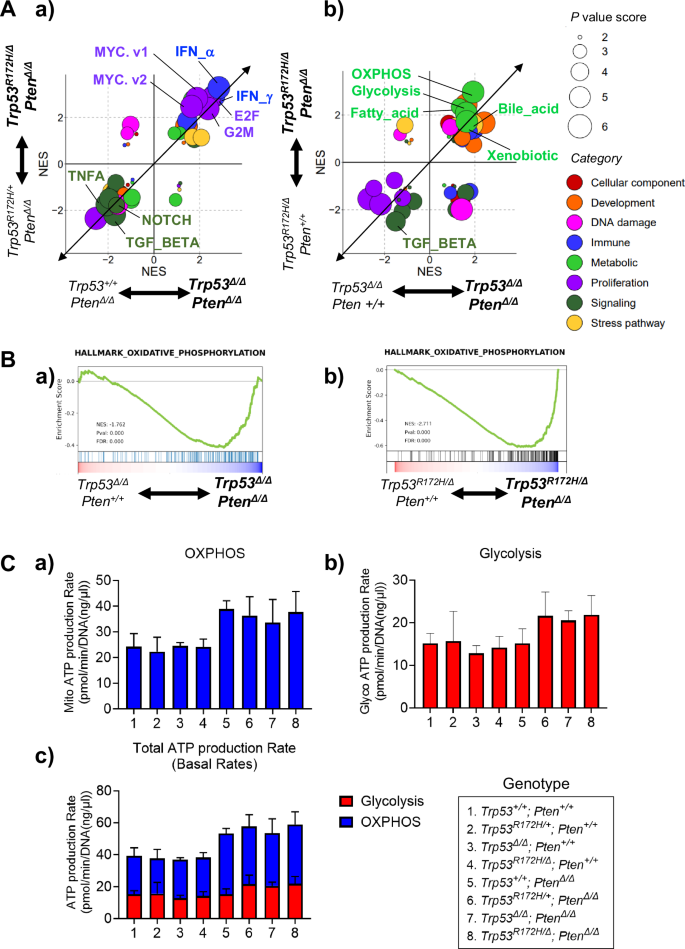

Alterations of Trp53 and Pten contribute to bladder cancer tumorigenesis through distinct mechanisms

Next, we investigated the biological mechanisms by which the loss of the WT Trp53 allele and deletion of Pten are each involved in K5-mUrorganoid tumorigenesis using RNA-seq and GSEA. K5-mUrorganoids of six different genotypes (Trp53R172H/+; Pten∆/∆, Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆, Trp53+/+; Pten∆/∆, Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆, Trp53R172H/∆; Pten+/+, and Trp53∆/∆; Pten+/+) were subjected to RNA-seq analysis (n = 4 for each genotype). To investigate the functional loss of the WT Trp53 allele, comparisons were made in GSEA between Trp53R172H/+; Pten∆/∆ and Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆, as well as between Trp53+/+; Pten∆/∆ and Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ (Fig. 3A-a). To investigate the functional loss of Pten, comparisons were made between Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ and Trp53R172H/∆; Pten+/+, as well as between Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ and Trp53∆/∆; Pten+/+ (Fig. 3A-b).

A The enrichment patterns found using Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) are depicted for the K5-mUrorganoid genotypes. The normalized enrichment score (NES) for each comparison between the indicated genotypes was expanded and exhibited in the scatter plots. The size of each dot indicates the sum of the P-value score based on the P-value (1, not significant; 2, P < 0.05; 3, P < 0.01) of the horizontal axis and the vertical axis. The categories were determined according to the original report [64] and differentially colored as indicated. a) Gene sets differentially enriched for the WT Trp53 allele status. b) Gene sets differentially enriched for the Pten status. B Oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) was significantly upregulated in K5-mUrorganoids with Pten loss. C Column charts showing the results of Seahorse adenosine triphosphate (ATP) assays for (a) OXPHOS, (b) glycolysis, and (c) total ATP production rates for K5-mUrorganoids with the indicated genotypes. The ATP production rate from OXPHOS and total ATP production rate were significantly higher in the organoids with Pten loss than in the Pten WT organoids (P = 0.002 and 0.001, respectively). See also Supplementary Figs. S11 and S12.

Among the hallmark gene sets for GSEA, the proliferation-related (NES; E2F_TARGETS 2.43–2.76, G2M_CHECKPOINT 2.37–2.38, MYC_TARGETS_V1 1.87–2.81, MYC_TARGETS_V2 1.64–2.47, Fig. 3A-a, S11A/B) and interferon response (NES; INTERFERON_ALPHA_RESPONSE 2.84–3.28, INTERFERON_GAMMA_RESPONSE 2.63–2.92) gene sets were significantly enriched in the K5-mUrorganoids with Trp53 WT allele loss, which was consistent with previous reports [21,22,23]. On the other hand, several tumor suppressive pathways including TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB (NES −2.05 to −1.75), TGF_BETA_SIGNALING (NES –1.71 to –2.18), and NOTCH_SIGNALING (NES −1.66 to −1.94) were significantly inversely enriched in the K5-mUrorganoids with Trp53 WT allele loss, which was also consistent with previous reports [24,25,26].

The gene sets involved in the metabolic category, including oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), glycolysis, fatty acid, bile acid, and xenobiotic, were significantly enriched in the K5-mUrorganoids with Pten loss (Figs. 3A-b, S11C/D). On the other hand, TGF_BETA_SIGNALING (NES −1.51 to −2.49) was also inversely enriched in the K5-mUrorganoids with Pten loss. Additionally, we found that the reactive oxygen species (ROS) pathway was significantly upregulated on Pten loss (GOBP_REACTIVE_OXYGEN_SPECIES_METABOLIC_PROCESS; Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ vs Trp53R172H/∆; Pten+/+; NES 1.7908, p < 0.01, Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ vs Trp53∆/∆; Pten+/+; NES 1.9203, p < 0.01). Because both OXPHOS and glycolysis pathway genes were enriched in K5-mUrorganoids with Pten loss (Fig. 3B), we then examined the mitochondrial ATP production rate using organoids with eight different genotypes (indicated in Fig. 3C). Seahorse flux analysis showed significantly higher mito (OXPHOS) ATP production rates in organoids with Pten loss, regardless of Trp53 status (Pten status; Two-group comparison of 1–4 vs. 5–8, P = 0.0021, Trp53 status; Four-group comparison of 1–2, 3–4, 5–6, and 7–8, P = 0.527, multiple regression analysis, Fig. 3C-a). The ATP production rate via glycolysis was also higher in K5-mUrorganoids with Pten loss compared with those expressing Pten, although the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.0616, Fig. 3C-b). The Trp53 status did not affect ATP production rate by glycolysis (P = 0.6067, Fig. 3C-b). Overall, the total ATP production rate was significantly higher in K5-mUrorganoids with Pten loss regardless of Trp53 status (Pten status; P = 0.0012, Trp53 status; P = 0.533, multiple regression analysis, Fig. 3C-c, see also Fig. S12).

Taken together, these results suggest that Pten loss and WT Trp53 allele loss in the organoids resulted in a cellular metabolic shift and acceleration of cell proliferation that supported tumorigenesis.

Trp53

R172H/∆

; Pten

Δ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids, but not Trp53

∆/∆

; Pten

Δ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids, can form tumors by direct inoculation in immunocompetent mice

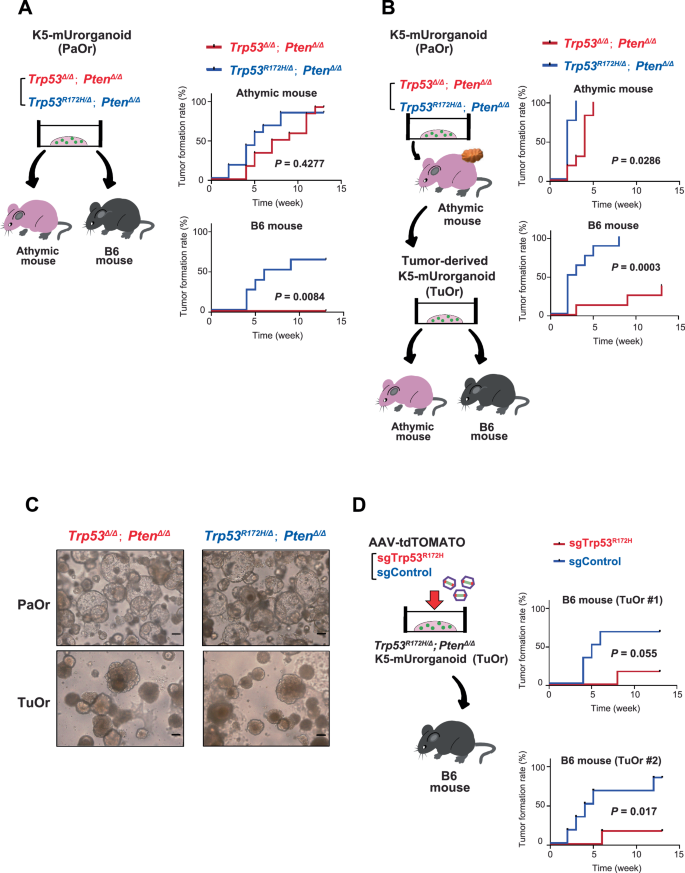

Various immunotherapies, including PD-1/PD-L1-targeting drugs, have been introduced for treating urothelial cancers [4, 27], and thus there is an increasing need for animal models with normal immune systems. Therefore, we investigated whether the Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ and Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids were able to form tumors in the immunocompetent B6 (C57BL/6NJcl) mice (n = 8 each, Fig. 4A, left). Both Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ and Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids did not significantly differ in the tumor formation rate (83.3% vs. 91.7%, P = 1.000, Fisher’s exact test) or time to tumor formation (5 vs. 8 weeks, P = 0.4277, log-rank test) in athymic mice (Fig. 4A, right top and S13A, left top). Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids formed tumors in immunocompetent B6 mice at a comparable rate to those in athymic mice (62.5%, n = 8), whereas none of the Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids (n = 8) formed tumors in B6 mice (tumor formation rate; P = 0.0256, Fisher’s exact test, time to tumor formation; 7.5 weeks vs. not reached, P = 0.0084, log-rank test, Fig. 4A, right bottom and S13A, right top). Our results indicate that Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids can genetically and morphologically recapitulate the basal-squamous human MIBC subtype, as well as be potentially useful as an experimental tool, particularly for immuno-oncology research.

A Schematic design of the experiment (left) showing that 1 × 106 cells of K5-mUrorganoids (Parent organoid; PaOr) with the indicated genotypes were inoculated subcutaneously into athymic (n = 12) or B6 (n = 8) mice. Kaplan–Meier curves (right) showing the time to tumor formation in athymic (top) and B6 (bottom) mice. B Schematic design of the experiment (left) showing that tumor-derived organoids (TuOrs) were generated from PaOr tumors grown in athymic mice. Here, 1 × 106 cells of TuOrs with the indicated genotype were inoculated subcutaneously into athymic (n = 8) or B6 (n = 8) mice. Kaplan–Meier curves (right) showing the time to tumor formation in athymic (top) and B6 (bottom) mice. C Representative bright-field microscopic images of PaOrs and TuOrs with the indicated genotypes. Scale bars indicate 100 μm. D Schematic design of the experiment (left) showing that AAV-sgTrp53R172H or sgControl was used to infect two independently generated Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs. These organoids were inoculated subcutaneously into athymic (n = 6) or B6 (n = 6) mice. Kaplan–Meier curves (right) showing the time to tumor formation for each TuOr. See also Supplementary Figs. S13 and S14.

We next investigated whether cells collected from the tumors formed in athymic mice had acquired a higher tumor-forming ability. For that purpose, we collected cells from tumors that originated from K5-Urorganoids (parental organoids; PaOrs) and were grown in athymic mice, then successfully generated secondary organoids (tumor-derived organoids; TuOrs, Fig. 4B, left). Both Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ and Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOrs formed tumors in athymic mice, with a shorter time to tumor formation for Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOrs than Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOrs (2 vs. 4 weeks, P = 0.0286, log-rank test, Fig. 4B, right top and S13A, left bottom). Relative to the corresponding PaOrs, TuOrs formed tumors at comparable rates (83.3 vs. 100%, P = 0.4947 for Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids and 91.7 vs. 100%, P = 1.000 for Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids, Fisher’s exact test), but did so more rapidly (median time to tumor formation for PaOrs vs. TuOrs; 5 vs. 2 weeks for Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids, P = 0.0002, and 8 vs. 4 weeks for Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids, P = 0.0002, log-rank test).

In immunocompetent B6 mice, Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOrs maintained a tumor-forming ability. The Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOrs acquired a tumor-forming ability, although the tumor formation rate (100 vs. 37.5%, P = 0.0256, Fisher’s exact test) and median time to tumor formation (2.5 weeks vs. not reached, P = 0.0003, log-rank test, Fig. 4B, right bottom and S13A, right bottom) were significantly lower than those of Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOrs. Relative to the corresponding PaOrs, Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOrs formed tumors at a comparable rate (62.5 vs. 100%, P = 0.2), but did so more rapidly (median time to tumor formation for PaOrs vs. TuOrs; 7.5 vs. 2.5 weeks, P = 0.0062, log-rank test). Similarly, 37.5% of Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOrs formed tumors, while the corresponding PaOrs did not (P = 0.2, Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.0628, log-rank test). These results indicate that, through the tumor formation process in athymic mice, the tumor-forming ability was enhanced in both Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ and Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids. Particularly, Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids acquired a tumor-forming ability in immunocompetent mice only after they had gone through tumor formation in athymic mice. Morphologically, PaOrs were characterized by a round regular shape with hollows, while TuOrs appeared irregular in shape and denser (Fig. 4C).

To further validate the association between the presence of the Trp53 R172H mutant and a higher tumor-forming ability in immunocompetent mice, we next used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to knock out Trp53 R172H expression in two independent lines of Trp53R172H/∆; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs derived from different tumors that were developed in athymic mice. We then evaluated the tumor-forming ability in immunocompetent B6 mice (Fig. 4D, left). Consistent with the Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ K5-mUrorganoids, TuOrs with Trp53 R172H knocked out showed an inferior tumor-forming ability to TuOrs treated with control sgRNA (Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOr #1; tumor formation rate; 66.7 vs. 16.7%, P = 0.2424, Fisher’s exact test, time to tumor formation; 5.5 weeks vs. not reached, P = 0.055, log-rank test, Fig. 4D, right top and S13B, left, n = 6 each; Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOr #2; tumor formation rate; 83.3 vs. 16.7%, P = 0.0801, Fisher’s exact test, time to tumor formation; 4.5 weeks vs. not reached, P = 0.0017, log-rank test, Fig. 4D, right bottom and S13B, right, n = 6 each).

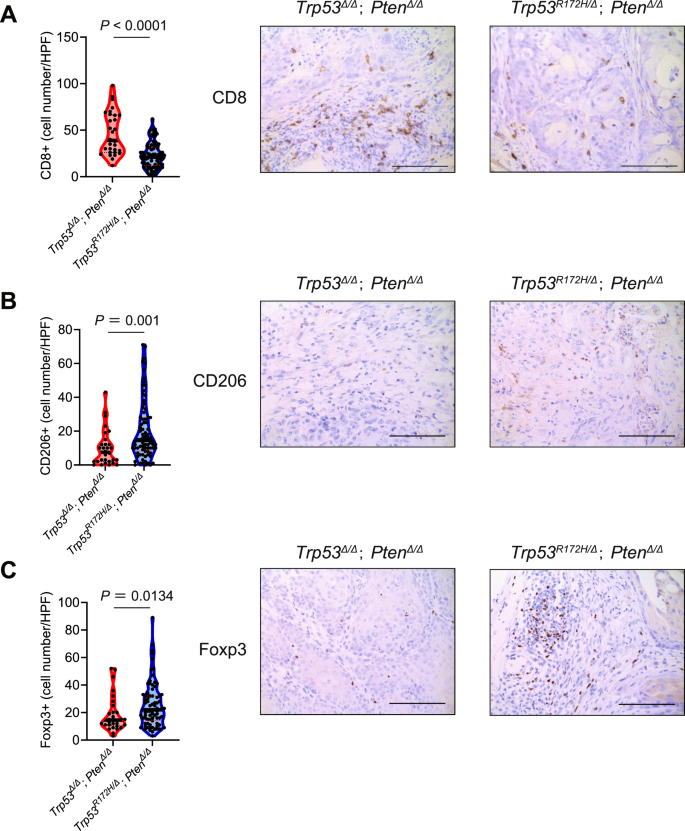

Next, we wanted to further explore the specific immunological mechanisms underlying the differential tumor-forming ability between Trp53R172H-expressing and Trp53-null K5-mUrorganoids, particularly in the tumor microenvironment. Using tumor tissues derived from Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ and Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOrs inoculated in B6 mice, we evaluated immune cell infiltration using IHC assays. Tumors derived from Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs showed less infiltration of CD8+ lymphocytes (median cell number/high-power field (HPF); 39 vs. 21, P < 0.001, Wilcoxon test, Fig. 5A), higher M2 macrophage marker expression (CD206, 14.5 vs. 7.5, P = 0.001, Wilcoxon test, Fig. 5B), and higher regulatory T cell (Treg) marker expression (Foxp3, 22 vs. 14.5, P = 0.0134, Wilcoxon test, Fig. 5C) compared with those from Trp53Δ/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs. H&E staining and IHC assays for Ck5 and p63 confirmed that both Trp53R172H/∆; Pten∆/∆ and Trp53∆/∆; Pten∆/∆ TuOr-derived tumors maintained the morphological features of the human MIBC basal-squamous subtype (Fig. S14).

The number of infiltrated cells (left) and representative images (right) of immunohistochemistry assays using A anti-CD8, B anti-CD206, and C anti-Foxp3 antibodies. Scale bars indicate 100 μm.

These results suggest that the differential tumor-forming ability between Trp53R172H-expressing and Trp53-null K5-mUrorganoids is related to immuno-oncological mechanisms. This is a potential explanation for the higher prevalence of the mutant LOH genotype compared with the homozygous deletion in TP53 among human MIBC cases. Additionally, we have demonstrated that both Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ and Trp53Δ/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs can be tumorigenic in immunocompetent mice with different tumor microenvironment profiles. Taken together, the K5-mUrorganoid is a promising model of human basal-squamous MIBC that is useful for further understanding the carcinogenesis process and establishing preclinical models of immuno-oncological treatment methods for this understudied disease.

Mutant Trp53-expressing organoids have decreased secretion of cytokines that mediate inflammation and CD8+ T cell activation compared with Trp53-null organoids

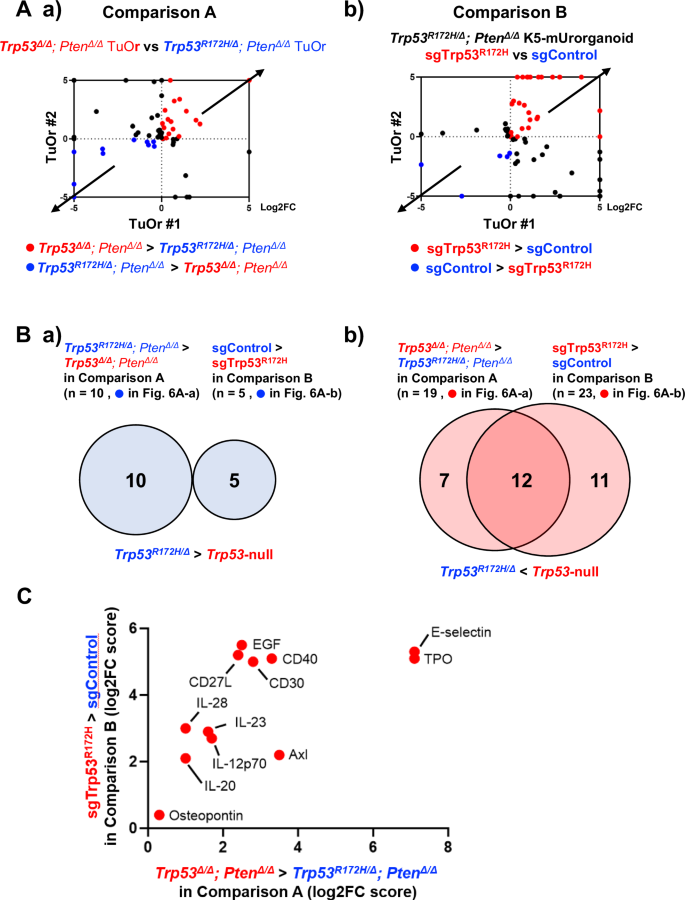

To further differentiate the immuno-oncological characteristics of Trp53R172H-expressing and Trp53-null TuOrs, we performed a cytokine array. First, we compared Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ and Trp53Δ/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs (comparison A) using two distinct TuOr lines for each genotype (#1; TuOr derived from female GEM, #2; TuOr derived from male GEM). Second, using two distinct TuOr lines (comparison B, #1; TuOr derived from female GEM, #2; TuOr derived from male GEM, see also Fig. 4D, left), we compared Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids treated with AAV-tdTOMATO expressing the control sgRNA (sgControl) with those treated with AAV-tdTOMATO expressing sgRNAs for Trp53R172H/Δ (sgTrp53R172H).

The comparison A helped us identify 10 cytokines that were elevated in Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs compared with Trp53∆/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs (Fig. 6A-a, blue dots, and Supplementary Table S2A-a), as well as 19 cytokines that were decreased in Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs compared with Trp53∆/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs (Fig. 6A-b, red dots, and Supplementary Table S2A-b). Similarly, the comparison B indicated that five cytokines were elevated in Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids treated with sgControl compared with those treated with sgTrp53R172H (Fig. 6A-b, blue dots, and Supplementary Table S2B-a). Additionally, 23 cytokines were decreased in Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids treated with sgTrp53R172H compared with those treated with sgControl (Fig. 6A-b, red dots, and Supplementary Table S2B-b).

A. a) Log2 fold-change (Log2FC) in cytokine expression levels of Trp53Δ/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs relative to Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs (comparison A) from female (horizontal axis, TuOr#1) and male (vertical axis, TuOr#2) mice. b) Log2FC in cytokine expression levels of Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs treated with sgTrp53R172H relative to those treated with sgControl (comparison B). The blue dots represent the cytokines increased in TuOrs expressing Trp53R172H/Δ, while the red dots represent the cytokines increased in TuOrs expressing no Trp53. B. Venn diagrams for (a) upregulated and (b) downregulated cytokines in K5-mUrorganoids expressing mutant Trp53 compared with those expressing no Trp53 commonly between comparisons A and B. C. List of 12 cytokines that were downregulated in K5-mUrorganoids expressing mutant Trp53 compared with those expressing no Trp53 commonly between comparisons A and B. The bars represent Log2FC. See also Supplementary Figs. S15.

No cytokine was found to be commonly elevated between Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs (comparison A, n = 10) and Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids treated with sgControl (comparison B, n = 5) (Fig. 6B-a and Supplementary Table S2). In contrast, 12 cytokines were increased in both Trp53Δ/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs compared with Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ TuOrs (comparison A, n = 19) and Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids treated with sgTrp53R172H compared with those treated with sgControl (comparison B, n = 23) (Fig. 6B-b, C). Among these 12 cytokines, CD27L, IL-12p70, IL-23, and Osteopontin have been reported to have functions related to inflammation or the recruitment and activation of CD8+ T cells [28,29,30,31]. Some previous reports have shown that mutant p53 variants transcriptionally regulate genes related to tumor immune microenvironment differently from wild-type p53 [32, 33]. We also performed qPCR using parent organoids with eight distinct genotypes to decipher R172H transcriptional differences from WT p53. We found that some of those genes including Lgals9 (coding Galectin 9, a ligand of TIM3) and Ccl5 were differentially expressed according to Trp53 status, but regardless of Pten status (Fig. S15), which was also correlated with tumor-forming ability in immune-competent mice.

Collectively, the results of our multiple comparisons between mutant Trp53-expressing and Trp53-null organoids showed decreased secretion of cytokines that mediate inflammation and CD8+ T cell activation in mutant Trp53-expressing organoids compared with Trp53-null organoids. These data are consistent with a higher prevalence of TP53-mutant LOH in human MIBC tumors and a higher in vivo tumor-forming ability of Trp53-mutant LOH organoids, particularly in immunocompetent mice, compared with p53-null cases.

Discussion

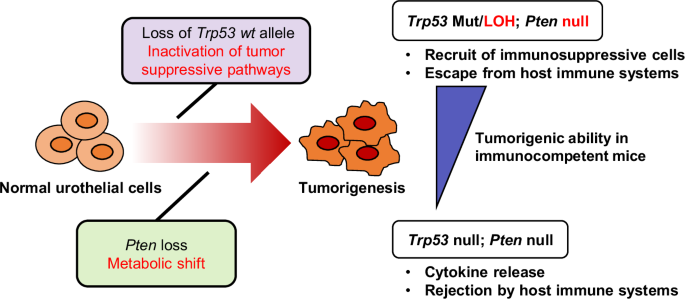

In the present study, we have demonstrated the clinical and biological significance of p53 missense mutations with LOH (loss of the p53 WT allele), as well as functional loss of Pten. Furthermore, with our findings, we have proposed a novel immunocompetent animal model for human MIBC that can be easily used to test hypotheses regarding the molecular mechanisms of urothelial cancer biology, particularly in the context of immuno-oncological research. In immunocompetent mice, tumors from Trp53 R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ organoids had higher tumor formation rates with less immune cell infiltration compared with Trp53Δ/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ organoids, suggesting that Trp53 mutations with LOH provide an advantage to the developing tumor compared with the homozygous loss of Trp53 (Fig. 7).

Pten loss in normal urothelial cells causes a metabolic shift, while a Trp53 missense mutation followed by loss of heterozygosity (LOH) promotes cell proliferation and a tumor-forming ability. The K5-mUrorganoids with mutant Trp53 with LOH release relatively lower levels of cytokines compared with the Trp53-null organoids, creating an immune-cold tumor microenvironment that favors tumorigenesis.

Studies have shown that there is a high prevalence of p53 LOH in conjunction with missense mutations, as evidenced by 93% of human cancers harboring a p53 mutation with loss of the WT p53 allele [34, 35]. The results of the TCGA analysis in the present study showed that at least 80% of cases with a p53 mutation demonstrated LOH. Nonetheless, to date, bladder cancer research has almost exclusively used Trp53-null models. Additionally, research on the difference in biological significance between Trp53 missense LOH and Trp53-null is limited. This study has provided an explanation to the phenomenon in which mutant LOH is much more dominant than deletion for p53 gene in human carcinoma by combining not only the tumor intrinsic mechanisms but also the effects on the tumor immunological microenvironment.

Previous reports on other malignant diseases have shown that cells with Trp53 LOH became increasingly predominant under stress conditions, such as passaging, irradiation, and in vivo transplantation, as a part of a selection process in tumor formation [36,37,38,39]. This suggests that the p53 LOH, in conjunction with missense mutations, universally confers an advantage to cancer cells in escaping biological stress. However, the underlying mechanisms appear to be diverse or context dependent. Most recently, Nakayama et al. demonstrated the enrichment of Trp53 LOH cells in metastatic tumors in a colon cancer mouse model [40, 41]. Compared with Trp53-null cells, Trp53 LOH cells showed upregulation of the stem cell signature, with enrichment of inflammatory and growth factor/MAPK pathways. This facilitated dormant cell survival and the tumor-initiating ability.

Our work here using K5-mUrorganoids is consistent with previous reports regarding the enrichment of Trp53 LOH cells through passages, which can eventually confer the in vivo tumor-forming ability. According to the pathway analysis of K5-mUrorganoids, loss of WT p53 was associated with an enrichment of genes involved in the c-Myc pathway. WT p53 can reportedly suppress c-Myc at multiple levels, including transcriptionally [22, 23] and post-transcriptionally [21]. Additionally, several gain-of-function p53 mutants, including R172H, have been reported to enhance c-Myc expression via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [42]. Additionally, our pathway analyses suggest that loss of Trp53 wild-type allele induce inactivation of various tumor-suppressing pathways.

The present study has demonstrated a new example of tumor-promoting mechanisms, which have attracted attention in recent years [43,44,45], that cancer driver gene mutations and activation of cancer-promoting signal transduction pathways modulate not only tumor-intrinsic phenotypic changes but also host tumor immunity in the tumor microenvironment. The Trp53R172H/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ K5-mUrorganoids demonstrated a higher engraftment rate than the Trp53Δ/Δ; PtenΔ/Δ strain in immunocompetent syngeneic mice, whereas these two genotypes exhibited a nearly equivalent engraftment rate in athymic mice. The high frequency of Trp53 missense LOH in human MIBC cases may be related to tumor immune escape-related mechanisms. Our further investigation revealed that the Trp53 missense LOH tumors had lower cytokine release, less infiltration of CD8+ T cells, and higher infiltration of immunosuppressive cells, including M2 macrophages and Tregs. Our results are supported by previous reports, which showed that mutant p53 can suppress anti-tumor immune responses [46]. Additionally, tumors with mutant p53 were found more likely to be immune-excluded compared with p53-null tumors [47, 48]. Various mechanisms for this phenomenon have been proposed, including suppression of innate immune responses [47], inhibition of cytokine release [48], and promotion of immunosuppressive neutrophil recruitment [49]. The impact of Trp53 status upon epigenetic regulation may also be intriguing based on our WES results and the previous report [12]. However, the exact mechanism may vary depending on the context [50].

Our current findings are not limited to the modeling of human MIBC with p53 missense LOH or its facilitating evasion of anti-tumor immunity. Bladder cancer models in immunocompetent animals have been limited to the BBN chemical carcinogenesis [51] model and certain GEM models [8, 9, 11]. Compared with conventional models, our model is characterized by several advantages for experimental use. First, K5-mUrorganoids can be cryopreserved. Additionally, the in vivo tumor formation rate is consistently high, with a short and uniform time to tumor formation. A tumor can form at any location, such as subcutaneously, orthotopically, or renal subcapsularly. Furthermore, this system has a “clean” genetic background consisting of a small number of genetic mutations. In urothelial carcinoma, anti-PD-1/PD-L1 drugs have been adopted as the standard treatment approach [4, 27]. Modeling diseases and treatments using immunocompetent animals is essential for predicting the therapeutic effects of immunotherapy and elucidating resistance mechanisms. Our experimental results will undoubtedly greatly contribute to contemporary urothelial cancer research [6].

The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway is known as a critical factor for cancer metabolism, such as glycolysis (Warburg effect), the pentose phosphate pathway, fatty acid synthesis, tricarboxylic acid cycle, glutaminolysis, and OXPHOS. A clinically aggressive subgroup of non-invasive bladder cancer, which develops via a distinct molecular pathway from that of invasive bladder cancer [5], was reportedly characterized by aberrant activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and increased glycolysis [52]. However, the specific impacts of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway on individual metabolic mechanisms are complicated and poorly understood, particularly in MIBC development. Here, we have demonstrated that Pten loss enriched expression of genes in the OXPHOS pathway and increased both the Mito and Glyco ATP generation rate. These findings are consistent with those of a previous report, which showed that the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway can positively regulate the OCR in head and neck cancer [53]. Another interesting fact is that the ROS pathway was also significantly upregulated on Pten loss, which potentially could be one of the factors to drive Trp53 LOH and tumorigenesis. This metabolic pathway may therefore be a promising target for new therapeutic strategies in MIBC, and our model may be a useful tool for investigating such approaches.

Our comparison of driver genes between human and mouse MIBC identified several KMT2-family genes with KMT2C as the most common gene between species. However, Kmt2c loss did not contribute to the tumor formation of K5-mUrorganoid. Since higher proliferation ability was shown in Trp53R172H/+ K5-mUrorganoid organoids deficient of both Kmt2c and Pten compared with those deficient of Pten alone, we assume that Kmt2c mutation may contribute to urothelial carcinogenesis in other way or context, which we hope to address in the future studies. According to the previous report, p53 is known to function as a co-activator of ASCOM [12]. Although this study did not directly investigate the role of p53 on ASCOM, it might be plausible that the p53 status could influence epigenetic regulation. Future studies using p53-chromatin immunoprecipitation along with an H3K4me profiling will be informative in the future.

We first generated organoids from Krt5-expressing mouse urothelial cells with the hypothesis that these are the originating cells of the human MIBC basal-squamous subtype. To trace the lineage, Krt5-expressing cell-specific Cre recombination was performed in vivo, followed by organoid generation and subsequent sorting for GFP+ cells. Because Krt5 is expressed across various organs in the body, generating a Krt5+ cell-derived autochthonous bladder cancer model was challenging. This approach led to the premature death of mice from other cancers developing before bladder cancer [11]. However, using an organoid culture system enabled the enrichment of bladder Krt5+ cells harboring the targeted genetic mutation, which helped overcome this problem.

We also previously attempted in vivo gene editing by injecting AAVs into mouse bladders, but the editing efficiency remained low and sufficient carcinogenesis was not achieved [16]. Conversely, organoids facilitated ex vivo gene editing using the CRISPR/Cas9 system and subsequent sorting allowed the aggregation of affected cells for transplantation back into the in vivo context. Consequently, these organoids represented a tumor with squamous differentiation that reflected intratumoral heterogeneity [54, 55]. In recent years, RNA expression-based subtype classification has become important for studying tumor immunity in bladder cancer [13, 20, 56,57,58]. The RNA expression patterns of the K5-mUrorganoid tumors corresponded to the basal-squamous subtype.

Organoids are a powerful tool for modeling the cancer initiation and progression processes [59,60,61]. In the ex vivo setting, organoid models offer an advantage of facile editing by applying CRISPR technology to investigate differences in phenotypes. Furthermore, a diverse range of assays can be feasibly performed using solely pure cancer cells, as demonstrated in this study. In the in vivo setting, obtaining uniformly sized tumors within 1–2 months using the syngeneic model can support drug testing and investigations into the tumor microenvironment, similarly to the established practices with cell lines [11]. Indeed, murine organ-derived organoids have been used for various types of cancer research to examine mechanisms of tumorigenesis [62], progression [63], and metastasis [41], although their application in urothelial cancer research has been limited [9].

In summary, we established syngeneic mouse models from organoids derived from Krt5-expressing bladder urothelial cells of GEM. Trp53 LOH accompanied with a missense mutation and activation of the PI3K pathway were crucial factors for tumorigenesis. Given the high frequency of p53 missense mutations and PI3K pathway activation in human MIBC, our K5-mUrorganoid model closely mimics the clinical scenarios observed with this disease. Therefore, our mouse models are expected to serve as potent experimental tools for cancer immunobiology research in the bladder cancer field.

Materials and methods

Experimental procedures are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Responses