Quantum topological photonics with special focus on waveguide systems

Timeline of topological photonics in waveguide systems

Originating from solid-state physics, the concept of topology is increasingly being applied in the field of photonics, garnering widespread attention and giving rise to numerous novel applications. A seminal contribution in this domain involves the theoretical prediction of topological insulators. The concept of topological insulators originated with the discovery of the quantum Hall effect1,2,3,4,5. Although this effect was originally demonstrated in electronic systems, it could also be realized in bosonic systems (such as photonics). Through the manipulation of system parameters, the creation of an artificial magnetic field is achievable, resulting in the observation of the quantum Hall effect (QHE) and quantum spin Hall effect (QSHE) within two-dimensional photonic systems6,7,8,9,10.

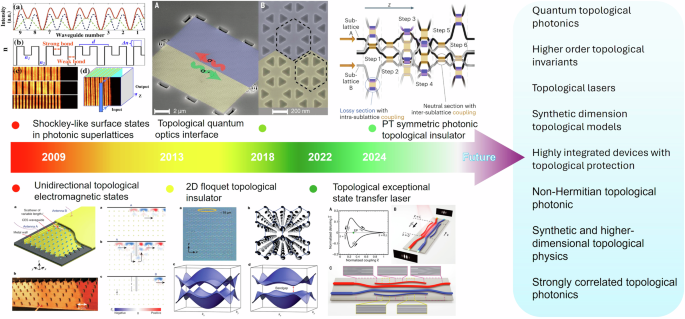

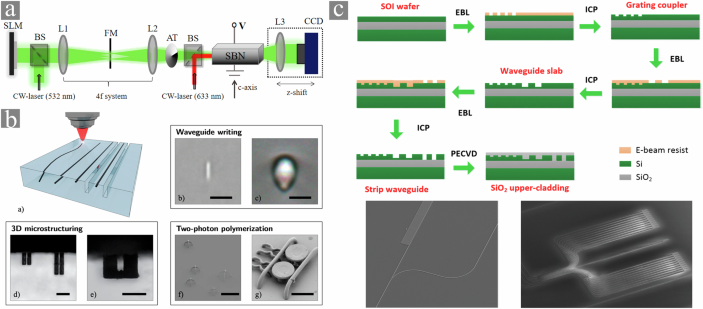

Throughout the evolutionary trajectory of topological photonics, the waveguide platform has assumed a pivotal role (Box 1). Based on photonic platforms, the unidirectional backscattering-immune topological electromagnetic states have been realized by implementing the chiral edge states in a gyromagnetic photonic-crystal slab, as shown in Fig. 18. In another context, photonic crystals consisting of gyromagnetic materials, such as yttrium iron garnet (YIG) were applied11. Under an additional uniform magnetic field B, the gyromagnetic response of the material will induce an effective magnetic field for photons in the microwave frequency range, which can be mapped to the Haldane model. Concurrently, in the year of 2009, the first experimental realization of Su–Schrieffer–Heeger (SSH) model12 in the photonic context was performed in a photonic superlattice13. Subsequently, a two-dimensional topological insulator was realized in a Floquet helical waveguide array through the utilization of the femtosecond laser direct writing method, as shown in Fig. 19. This progress culminated in numerous milestones in topological insulators such as the Anderson insulator14, fractal photonic topological insulator15,16, and bimorphic Floquet topological insulator17. Most recently, a significant advancement was made by introducing the periodic gain/loss into a two-dimensional system comprising 48 waveguides, the evidence of the existence of a non-Hermitian topological insulator with a real-valued energy spectrum has been presented in a Floquet regime, as shown in Fig. 118.

Shockley-like surface states in photonic superlattices13. Unidirectional topological electromagnetic states8. Floquet topological insulator9. Topological quantum optics interface assisted quantum emitter24. Topological exceptional state transfer laser55. PT-symmetric photonic topological insulator realized in a 2-dimensional waveguides array18. Panels adapted with permission from refs. 8,9,13,18,24,55.

In the meanwhile, coupled resonator optical waveguide (CROW) system also offers a great platform to study topological insulator phases, where the direction of propagation of light in each resonator functions as a spin. A resilient optical delay line featuring topological protection has been successfully implemented in a silicon photonics platform leveraging the QHE and QSHE principles10,19. In 2013, an important model of quantum anomalous Floquet Hall model was proposed20 and realized in the CROW system to demonstrate topologically protected entanglement emitters21. Most recently, a fully programmable topological photonic chip was realized using tunable microring resonators, and the platform showcased the capability to implement multifunctional topological models22. Another key model is a topological crystalline insulator23, which could introduce a topological quantum optics interface24.

Another platform worth mentioning is based on meta-waveguides. In 2013, a photonic analog of a topological insulator was theoretically proposed using metacrystals, demonstrating the potential for one-way photon transport without the need for external magnetic fields or breaking time-reversal symmetry25. Subsequently, in 2015, a simple yet insightful photonic structure based on a periodic array of metallic cylinders was developed to emulate spin–orbit interaction through bianisotropy26. This meta-waveguide platform does not suffer from high Ohmic losses and could potentially be scaled to infrared optical frequencies. This approach has proven fruitful for topological photonics, as evidenced by numerous experimental demonstrations27,28,29.

These insulators maintain insulation within their bulk while permitting the propagation of waves on their surfaces. They exhibit notable robustness to disorder and effectively impede back-scattering. The robust demonstration of the QHE and quantum anomalous Hall effect5,30 in terms of edge conductivity across various parameters serves as a compelling illustration of the predictions within this domain. The topological invariant known as the Chern number31 plays a crucial role in elucidating the aforementioned effects. It is the adept application of the winding number (one-dimensional systems) and the Chern number (even-dimensional systems) that establishes a profound theoretical foundation for topological photonics

where (A({{{bf{k}}}})=ileftlangle {u}_{{{{bf{k}}}}}leftvert {nabla }_{{{{bf{k}}}}}rightvert {u}_{{{{bf{k}}}}}rightrangle) represents the Berry connection32 in the momentum–space and P denotes the projector operator (P({{{bf{k}}}})={sum }_{i = 1}^{n}leftvert {u}_{i}({{{bf{k}}}})rightrangle leftlangle {u}_{i}({{{bf{k}}}})rightvert). These topological invariants keep the nature of the integer and only undergo a change when there is a closure of the band gap. Despite the myriad differences in properties such as dimensions, the number of waveguides, and shapes, photonic systems sharing the same topological invariants can often be categorized into a unified class, exhibiting consistent characteristics in key properties. Consequently, these integers serve as a manifestation of the robust attributes inherent in topological photonics systems against small continuous perturbations, for example, the defects in photonic device processing, or small changes in the refractive index of the material. Building upon this foundation, the exploration of methods to enhance the nonlinear effects in materials and the quest for novel invariants that could potentially confer topological protection to devices have increasingly become noteworthy endeavors within the realm of topological photonics based on photonics waveguide systems (Table 1).

In one-dimensional topological photonics systems, the emergence of topological phases is inevitably associated with the presence of symmetries33,34. A paramount one-dimensional model is the SSH model with a Hamiltonian denoted as

characterized by chiral symmetry. κ1 and κ2 denote the intra/inter-cell hopping amplitudes in this dimerized system. Further exploration has been undertaken in the photonic waveguide system regarding the topology associated with the winding number (or the Zak phase), including the interface between two dimer chains with different Zak phases35,36,37, localization behavior in SSH model with defects38, superlattice model with more sites (>2) in a cell39,40 and direct detection of topological invariant41,42,43.

Originating from the embodiment of topology in two-dimensional materials, chiral topological photonics also shows its potential rich application prospects44. Barik et al. achieved the realization of a chiral quantum emitter using InAs quantum dots, as shown in Fig. 1, thanks to the exploration of interface edge modes connecting two topologically distinct regions. This implementation involved the selective coupling of 900–980 nm white light to the grating coupler, while photons outside the bandgap dissipated to the bulk24. Additionally, a series of investigations in chiral topological photonics have been systematically conducted, building upon photonic waveguide systems45,46,47,48.

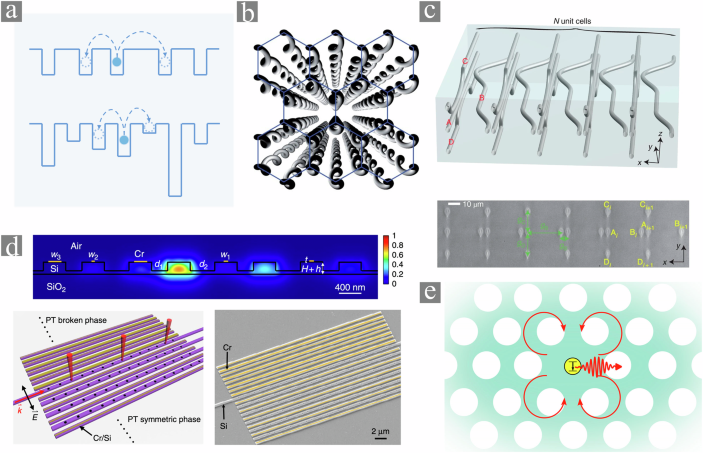

Another emerging area based on waveguide systems that have garnered widespread attention is PT-symmetric topological photonics, which provides a new perspective by considering gain and loss in optical systems. This emerging field has attracted considerable attention and the readers could find many nice review articles on related topics49,50,51,52,53,54. Leveraging the novel design motivated by exceptional points, a topological laser emitting in two different but topologically linked transverse profiles is realized through exceptional state transfer within two waveguides, as shown in Fig. 155. Inspired by the ongoing non-Hermitian physics in condensed matter, the non-Hermitian photonics, such as non-Hermitian skin effect incorporating non-Bloch band theory, will follow further56,57, apart from the PT topological insulator and PT-symmetric lasing58. Finally, we would like to point out another direction, that is, the interplay between topology and quantum optics (for instance, see ref. 59), and this is also the focus of this perspective.

Physics of photonic waveguide arrays

Photonic waveguides represent a cornerstone in the field of photonics, facilitating the controlled propagation of light (Box 2). These structures are capable of guiding light waves through the modulation of refractive indices, creating pathways that allow for the efficient transmission of optical signals. The underlying physics of photonic waveguide arrays is governed by the interplay between the wave nature of light and the geometrical/material properties of the waveguides themselves.

The behavior of light within these waveguides is described by Maxwell’s equations, which, under the approximation of a slowly varying envelope and assuming linear, isotropic, and non-dispersive media, can be reduced to the Helmholtz equation:

where ({nabla }_{x,y}^{2}) is the transverse Laplacian, φ(x, y, z) is the electric field envelope, kz is the propagation constant along the z-direction, k0 is the free space wave number, and n(x, y) is the refractive index distribution.

The coupling of light between adjacent waveguides in an array is described by the coupled-mode theory, which can be simplified under the tight-binding approximation to yield a set of discrete equations modeling the evolution of light amplitude in each waveguide:

where φi is the wave amplitude in the ith waveguide, βi is the propagation constant, and κi,j represents the coupling coefficient between the ith and jth waveguides.

Adjusting the on-site potential (βi) and the hopping terms (κi,j) allows for the meticulous control of light propagation. Variations in the on-site potential can lead to phase shifts within the waveguides, affecting interference patterns. Similarly, modifying the hopping terms influences the extent of light spread across the array, effectively controlling the bandwidth of the photonic band structure. By engineering the geometry and refractive index distribution of the waveguide array, it is possible to tailor the propagation characteristics of light. This framework allows for the exploration of various phenomena unique to waveguide arrays, such as bandgap formation, localization effects, and the emergence of topological edge states.

In addition to linear propagation, photonic waveguide arrays can exhibit complex dynamics due to nonlinear effects. When the intensity of light within the waveguides reaches a certain threshold, nonlinear phenomena such as self-phase modulation and soliton formation can occur. These effects can be described by introducing nonlinear terms into the coupled-mode equations, providing a rich avenue for the study of nonlinear optics in discretized systems. For a comprehensive exploration of the principles governing light propagation within photonic waveguide arrays, we kindly refer the readers to refs. 60,61.

Quantum states of light in topological waveguides

To maintain a focused perspective in this discussion, we will limit our exploration to systems that involve single or arrayed waveguides. This approach allows us to delve deeply into the specifics of these systems, examining their unique properties and applications without extending into the broader and more complex landscape of other optical systems. The generation of single and entangled photon pairs are cornerstones for quantum communication and computing. Entangled photon pairs emerge primarily from non-linear optical phenomena like spontaneous four-wave mixing and spontaneous parametric down-conversion. On the other hand, on-demand single photons are generated from atomic-like transitions in quantum dots, color centers, and 2-D emitters. As the exploration in quantum photonics forges ahead, it becomes increasingly clear that addressing the efficiency and quality of entangled photon-pair sources, and the uniformity and purity of single-photon sources are pivotal challenges. Surmounting these obstacles will not only enhance our understanding of the quantum world but also open avenues for more practical and scalable applications in quantum technologies.

Early theoretical studies highlighted the potential of photonic topological insulators to maintain the integrity of fragile multiphoton states in quantum walks62, which is vital for applications like Boson sampling, a process known for its potential exponential speedup in certain algorithms. In waveguide systems, topological protection of the two-photon state against decoherence was demonstrated63. The study reveals that in the topologically nontrivial boundary state of a photonic chip, two-photon quantum-correlated states are effectively preserved, exhibiting high cross-correlation and a strong violation of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality by up to 30 standard deviations. These findings highlight the robustness of topological protection against factors like photon wavelength difference and distinguishability. Moreover, the study in ref. 64 reports high-visibility quantum interference of single-photon topological states within an integrated photonic circuit, where two topological boundary states at the edges of a coupled waveguide array are brought together to interfere and undergo a beamsplitter operation. This process results in the observation of Hong–Ou–Mandel interference with a visibility of 93.1 ± 2.8%, demonstrating the nonclassical behavior of topological states. This significant achievement illustrates the practical feasibility of generating and controlling highly indistinguishable single-photon topological states. To confirm the resilience of topological biphoton states against disorder, the work in ref. 65 fabricated structures with varying levels of introduced disorder. The measured Schmidt number remains close to 1, underlined by the topology’s assurance of a single localized mode. These results not only underscore the importance of quantum correlation robustness but also spotlight the potential advantages of topological methods in quantum information systems. Entanglement protection was also demonstrated in refs. 66,67. In the latter, the team demonstrates topological protection of spatially entangled biphoton states. Utilizing the SSH model, the system exhibits strong localization of topological modes and spatial entanglement between them under varying levels of disorder, underscores the topological nature of these entangled states. The topological protection was extended to systems with quasi-crystal structures and sawtooth lattice, the non-classical features are safeguarded against decoherence caused by diffusion in interconnected waveguides and from the environment noise disturbances68,69. Similar ideas were extended to the generation of squeezed light70, a key component in quantum sensing and information processing. Due to the weak optical nonlinearity and limited interaction volume in bulk crystals, the study uses waveguide arrays to increase nonlinearity. The topologically protected pump light enables the waveguide lattice to operate effectively as a high-quality quantum squeezing device. In addition to path-entanglement, topological protection was realized for polarization-entangled photon pairs in a waveguide array lattice71. Additionally, in another waveguide-based system that utilizes valley photonic crystals (VPCs), topological protection of frequency entangled photons was realized72. The photon pairs were generated by four-wave mixing (FWM) interactions in topological valley states, propagating along interfaces between VPCs. Furthermore, theoretical studies showed that topological protection can be extended to dual degrees of freedom, specifically time and energy73. Such a demonstration highlights the potential of topologically protected quantum states in photonic systems, particularly for applications operating at telecommunication wavelengths.

In addition to photon pairs based on non-linear interactions, significant progress has been made in engineering the topological properties of photonic circuits hosting on-demand single photon sources and potentially solid-state optical memories. In a recent study24, the authors successfully demonstrate a powerful interface between single quantum emitters and topologically robust photonic edge states, a significant achievement at the intersection of quantum optics and topological photonics. Utilizing a device composed of a thin GaAs membrane with epitaxially grown InAs quantum dots acting as quantum emitters, the team creates robust counterpropagating edge states at the boundary of two distinct topological photonic crystals. A key result of their experiment is the demonstration of chiral emission of a quantum emitter into these modes, confirming their robustness against sharp bends in the photonic structure. This research not only exemplifies the successful coupling of single quantum emitters with topological photonic states but also highlights the potential of these systems in developing quantum optical devices that inherently possess built-in protection. Moreover, the work in ref. 74 developed a chiral quantum optical interface by integrating semiconductor quantum dots into a valley-Hall topological photonic crystal waveguide, showcasing the interface’s capability to support both topologically trivial and non-trivial modes. The convergence of nanophotonics with quantum optics has led to the emergence of chiral light–matter interactions, a phenomenon not addressed in conventional quantum optics frameworks. This interaction, stemming from the strong confinement of light within these nanostructures, results in a unique relationship where the local polarization of light is intricately linked to its propagation direction. This leads to direction-dependent emission, scattering, and absorption of photons by quantum emitters, forming the basis of chiral quantum optics. Such advancements promise novel functionalities and applications, including non-reciprocal single-photon devices with deterministic spin–photon interfaces44. The study showcases the potential of chiral quantum photonics in ref. 75. It successfully demonstrates that the helicity of a quantum emitter’s optical transition determines the direction of single-photon emission in a glide-plane photonic-crystal waveguide. The implications of this research are vast, including the construction of non-reciprocal photonic elements like single-photon diodes and circulators.

Topological protection of quantum resources

The field of topological photonics, inspired by groundbreaking concepts in quantum mechanics and solid-state physics, promised a revolution in controlling light propagation in photonic systems. The notion of harnessing topological properties to create backscattering-immune waveguides presented a paradigm shift, particularly in developing efficient quantum resources and enhancing photonic system performances. In nanophotonic waveguides, the precision of fabrication is challenged by the occurrence nanometer-level imperfections along the etched sidewalls. These imperfections, significantly smaller than the fabricated unit-cell, for example, in photonic crystal waveguide systems, cast doubt on the efficacy of employing topological protection strategies for quantum resources76. The backscattering mean free path (ξ) is essential for assessing photonic waveguides against nanostructural imperfections. It marks the threshold between efficient transmission with minimal scattering and significant backscattering when waveguide length (L) exceeds ξ. Such a figure of merit is imperative for substantiating the advantages of topological over conventional transport at the nanoscale77. Recent experimental evidence in ref. 76, showed significant backscattering in valley-Hall topological waveguides despite record low-loss waveguides. The persistence of backscattering raises fundamental questions about our understanding of light–matter interaction in topologically structured photonic environments. This necessitates rethinking the materials and designs used in photonic quantum technologies, potentially shifting focus towards alternative mechanisms for achieving topological protection. Addressing these challenges requires exploring beyond conventional topological paradigms. This might involve investigating new classes of materials, such as magneto-optic systems, to break time-reversal symmetry at optical frequencies. Despite these challenges, topologically non-trivial systems with non-broken time-reversal symmetry have been shown to outperform topologically trivial ones for certain disorder strength77. Such structures can offer a viable foundation for novel quantum logic architectures, resource robustness, non-reciprocal photonic elements, and efficient spin–photon coupling44,78,79 (Fig. 2).

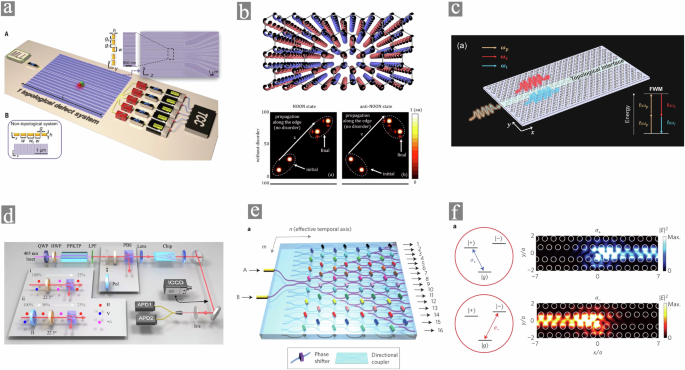

a Topological protection of biphoton states65. b Topological protection of path entanglement62. c Topological protection of continuous frequency entangled biphoton states72. d Topological protection of two-photon states against the decoherence in diffusion63. e Anderson localization of entangled photons in an integrated quantum walk66. f Topological light–matter interface75. Panels adapted with permission from refs. 62,63,65,66,72,75.

Quantum topological photonics: Looking ahead

What next for topological quantum photonics? As the field of quantum topological photonics continues to mature, the journey ahead is lined with both challenges and opportunities34,80,81,82,83. Building on the foundation laid by pioneering research in this field, the future direction is poised to explore novel paradigms and technologies that could further revolutionize photonics and quantum information processing. One of the most promising frontiers is the development of active tuning and dynamic control mechanisms within topological photonic structures84. Current research has predominantly focused on passive systems, where the topological properties are fixed once fabricated. However, the integration of active materials or mechanisms that allow for real-time control of topological features can dramatically enhance the versatility of photonic devices, and create synthetic dimensions85. Such advancements could enable reconfigurable photonic circuits, adaptable computing architectures, and dynamic communication networks. For instance, integrating electro-optic or thermo-optic materials into topological waveguides could provide a means to dynamically tune the band structure, thus controlling the propagation and interaction of photons in these systems86. Additionally, incorporating magneto-optic materials into topological photonics offers a powerful approach to breaking time-reversal symmetry87. Hybrid integration could pave the way for devices that exploit magnetic fields to control photonic states88. The exploration of materials with strong magneto-optical responses at room temperature and their seamless integration into photonic chips will be crucial in this endeavor89. With regard to quantum sources, the challenge that remains is enhancing the efficiency and uniformity of quantum sources, such as single-photon emitters and entangled photon pairs. Efforts should be directed toward improving the coupling efficiency between quantum emitters and photonic structures, minimizing losses, and increasing the purity of quantum states90. Research in developing more efficient non-linear materials for photon pair generation, along with better fabrication techniques for quantum dots and other emitters, will be vital91,92,93,94. The integration of topological photonics with quantum optics and information processing has already demonstrated significant potential. The next step is to develop complex quantum photonic systems that leverage topological protection for enhanced performance and new functionalities, with careful investigation of the figures of merits, and to benchmark their superior performance to topologically trivial devices. On a more fundamental level, future research should also focus on discovering new topological phases and experimenting with a wider range of materials. The exploration of 2D materials, such as graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides, offers exciting prospects for hosting topologically protected states with unique properties and building systems that rely on the interplay between electronic and photonic states78,95. Lastly, it is crucial to address fundamental questions raised by recent experimental observations, such as the persistence of coherent backscattering in topologically protected systems. This will require a deeper theoretical understanding of light–matter interactions in topologically structured environments and might lead to the development of new theoretical models and simulation tools. Moreover, the fusion of non-Hermitian physics with topological insulators reveals a plethora of novel phenomena and offers more approaches to optical device design. By harnessing the intricate balance of gain and loss within photonic systems, non-Hermitian topological photonics paves the way for manipulating topological states in unprecedented manners. Recent advancements and applications include the manipulation of topological phase transitions and the skin effect96. Additionally, quantum topological time crystals represent a transformative advancement in the manipulation of temporal properties for photonic applications. It leverages the periodic modulation of material properties, which gives rise to dispersion relations characterized by bands separated by momentum gaps, resulting in a class of non-conservation energy states due to broken time-translation symmetry. Quantum topological time crystals are poised to enable exciting new devices, including detectors of entangled states and generation of cluster states97.

Additionally, the concept of gain and time crystals can be combined, leading to amplified emission and lasing with narrowing radiation linewidth over time98. The research into such crystals, with loss/gain and temporal modulation, not only revisits the classical understanding of light–matter interaction but also proposes the intriguing concept of non-resonant, tunable lasers. These lasers, devoid of the traditional resonance requirements, can draw operational energy from the external modulation of the medium, presenting a versatile approach to laser design. Moreover, the study of strongly correlated photonic systems introduces a novel dimension to our understanding of quantum topological states. A standout achievement in this domain is the experimental realization of Laughlin states using light99. The control over light-matter interactions can have implications for different quantum technologies ranging from quantum computing to novel topological quantum devices.

In the rapidly advancing field of quantum topological photonics, the intersection of theoretical innovation and practical application paints a promising yet challenging future. This domain, rich with potential, stands at the forefront of revolutionizing information processing, communication technologies, and quantum computing, thanks to its predicted robustness against disturbances and its ability to manipulate light in novel ways. However, the path forward is not without its hurdles. Fabrication imperfections, scalability of systems, and the integration of quantum sources with topological structures remain significant challenges that demand meticulous attention and creative solutions. Additionally, the complexities of non-Hermitian dynamics, the realization of time crystals in practical settings, and harnessing the full potential of strongly correlated photonic systems require a deeper understanding and more sophisticated experimental techniques. Despite these challenges, the field of quantum topological photonics holds significant promise for advancing technology and science. As we continue to navigate its complexities, the potential for transformative breakthroughs remains vast, paving the way for a new era of photonic applications and discoveries.

Responses