Quasispecies theory and emerging viruses: challenges and applications

Introduction

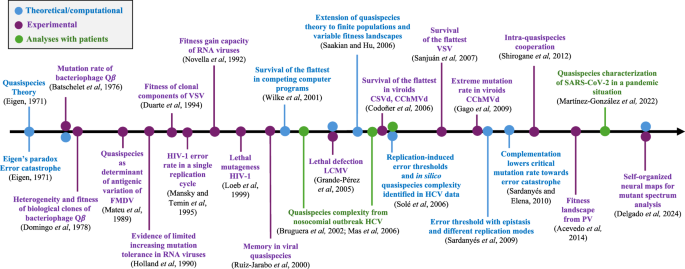

The quasispecies theory, conceived by Manfred Eigen and Peter Schuster more than fifty years ago1,2,3,4 was developed to investigate the dynamics of biological information in replicators subjected to exceptionally high mutation rates. This theory is a cornerstone in understanding prebiotic evolution and a new framework to investigate the genetic diversity of viruses and their dynamics5,6,7,8,9,10. Moreover, it also extends to the dynamics of cancer cells11,12,13 and has been linked to the conformational diversity of prions14. At its core, the theory posits that viral populations exist not as static entities with a single genome, but rather as dynamic distributions of closely related mutant genomes known as mutant swarms or quasispecies. The term diversity refers to genetic and phenotypic differences among clades or isolates of viruses from the same taxonomic group, or of the viral world (virosphere) in general. In contrast, quasispecies refers to a particular population structure that describes the genome diversity within a virus isolate or a laboratory population, its dynamical properties (including mutational coupling between genetic variants), and its consequences for virus evolution and pathogenesis. Viral populations are characterized by high mutation rates due to the limited template-copying fidelity of RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp) and RNA-dependent DNA polymerases (RdDp), leading to the continuous generation of genetic variants. The collective behavior of these variants, along with multiple selection pressures—such as heterogeneity in susceptible target cells, host immune systems, and potential antiviral therapies—and bottleneck events at various scales, together shape the evolutionary trajectories of the virus. Thus, understanding the quasispecies dynamics is essential for elucidating viral pathogenesis, transmission dynamics, and the emergence of drug resistance. The molecular quasispecies theory has driven the development of a comprehensive theory of virus evolution, supported and enriched by numerous experimental and clinical studies. Figure 1 shows a brief outline of some key contributions to viral quasispecies. The present article is intended for both theoreticians and experimentalists, and aims to provide a knowledge bridge between these audiences and both clinical and medical researchers. We review in an interdisciplinary manner the major historical developments of quasispecies theory, and new concepts that have arisen as the result of mutual influences between advances in experimental observations and theoretical aspects. We delineate some challenges in biomedicine related to the impact of quasispecies dynamics on disease control and the emergence of new viral pathogens. These points may also interest the medical community involved in investigations of viral disease mechanisms and therapeutic approaches.

Time arrow showing some key achievements in the development of quasispecies theory for viruses since its birth in 1971. The colors indicate whether the results have been achieved from theoretical/computational research (blue), from experimental data (violet), and/or from data from infected patients (green). CChMVd Chrysanthemum chlorotic mottle viroid, CSVd Chrysanthemum stunt viroid, FMDV foot-and-mouth disease virus, HCV hepatitis C virus, HIV-1 human immunodeficiency virus type-1, LCMV lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus, VSV vesicular stomatitis virus, PV poliovirus. See Refs. 133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143.

Research on bacteriophage Qβ by Charles Weissmann and colleagues in the 1970s15 coincided with the development of quasispecies theory by Eigen and Schuster; the two investigations were carried out independently. During the 1980s and 1990s, scientists compared genomic sequences of clones from natural viral isolates or experimental viral populations. The introduction in the 2000s of ultra-deep sequencing significantly advanced the understanding of the genetic complexity of the mutant swarm. The quasispecies concept has profound implications for clinical and public health interventions. By viewing viral populations as dynamic ensembles of genetic variants rather than static entities, the quasispecies theory underscores the challenges to eradicating viral infections through conventional interventions. Antiviral therapies that target a single viral genotype may exert a selective pressure, favoring the emergence of drug-resistant mutants within the cloud of mutants forming the quasispecies. This evolutionary resilience necessitates the development of novel therapeutic strategies that take into account the complex evolutionary dynamics of viral populations. Additionally, insights from the quasispecies theory have led to advancements in experimental and computational techniques for characterizing viral diversity. These improvements allow for more precise monitoring of viral evolution and help design programs to reduce the spread of viral pathogens.

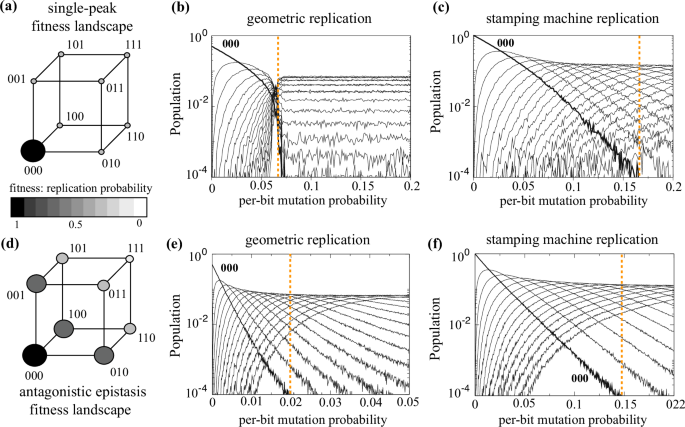

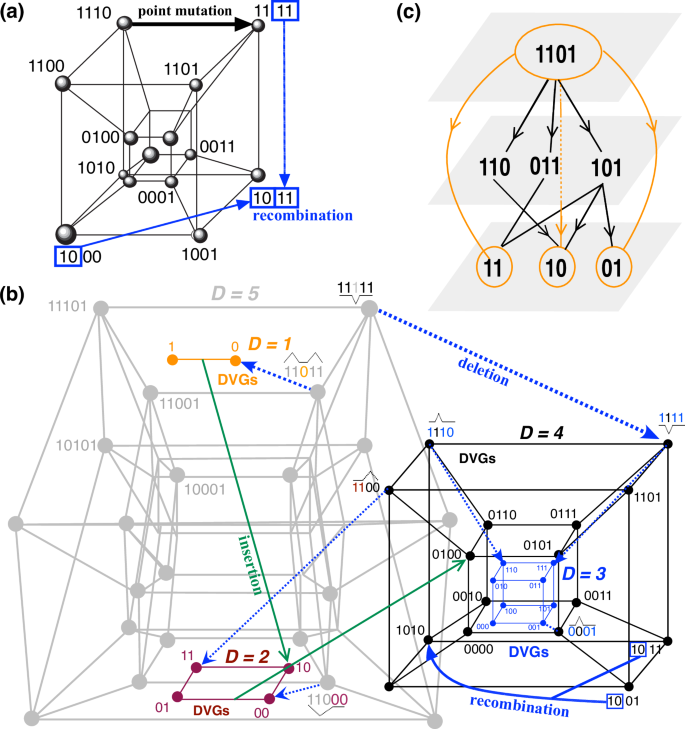

Two related key concepts in quasispecies theory are the so-called sequence spaces and fitness landscapes. The sequence space is a multidimensional discrete space, also called a hypercube, where each node corresponds to a given genotype, which is connected to the neighboring genotypes by single-point mutations16 (Fig. 2a, b and Fig. 3a). Viral fitness is the capacity of a virus to produce infectious progeny. It is often expressed as a relative value, taking as reference a population or clone of the same virus. It is an environment-dependent value, so it needs not to be identical when measured with different cell lines in culture, organoids, tissues, organs, or an entire host. Its value depends on multiple host and viral factors, including the mutant spectrum composition. The term “epidemiological fitness” was coined to refer to differences among viral strains (or clades, lineages, variants) to become dominant in the epidemiological setting where parameters other than replicative capacity (i.e., particle stability, transmissibility) also play a role. Because of these multiple influences, viral fitness varies with time. Also, the need to understand the structure of fitness landscapes17 applies to viral populations (different aspects of fitness have been reviewed in refs. 18,19).

a Single-peak fitness landscape (illustrated with a 3-bits hypercube). The size of the balls is proportional to the genotypes’ fitness. The quasispecies population plots show the error threshold for the single-peak fitness landscape for geometric (b) and stamping machine (c) replication. d Fitness landscape with antagonistic epistasis also for 3-bit genomes where the effects of mutations are less severe in combination than individually. Here, we also display the error threshold for geometric (e) and stamping machine (f) replication modes. All the diagrams show the stationary populations of the master sequence (000, thick lines) and the pool of mutants (with 1, 2, or 3 mutations, thin lines) averaged over 200 replicas at increasing the per-bit mutation probability. The dashed orange lines indicate the critical per-bit mutation rate causing the error threshold. See Ref. 50 for further details.

Generically, the order of a hypercube is nL, n being the number of letters in the alphabet (4 for nucleotides) and L the length of the genome (the number of bases in the sequence, which determines the dimension of the hypercube). That is, the order of the sequence space for an RNA virus with a short genome, such as bacteriophage MS2, with 3569 nucleotides, results in a hypercube with 43569 connected nodes. This is a huge sequence space that can be explored by the virus through the processes of point mutations or recombination events that do not alter the genome length (Fig. 3a). Each of the nodes of this hypercube thus corresponds to a different genotype with a given fitness. It is known that point mutations can impact the fitness of the viral genotypes, typically being deleterious or lethal20,21,22,23,24,25. The quasispecies is expected to be located in a given region or regions of this multidimensional space after selection takes place. As we discuss below, these hypercubes may not accurately describe the complexity of quasispecies when considering other genetic processes, such as deletions or insertions, which result in viral genomes of varying lengths. Hence, the quasispecies should be expected to live in a much more complex sequence space that we define as the ultracube and will explain below.

a Classical view of quasispecies evolution in a hypercube for 4-bit sequences. Each node of the network connects two genotypes via a single-point mutation. Sequences evolve to first neighbors by single-bit (nucleotide) substitutions during replication. Homologous recombination may allow genotypes to jump to further neighbors (blue arrow). b Example of a sequence space for binary genomes of length five considering deletions (blue dashed arrows) and insertions (green solid arrows) during replication. These processes produce mutants and connect hypercubes of different dimensions, giving rise to a more complex sequence space that we label ultracube and which can be conceived as a multiplex network. For clarity, we do not display all the nodes but exemplify some processes of deletion and insertion, which give rise to a set of connected hypercubes of dimensions 5 (gray), 4 (black), 3 (blue), 2 (red), and 1 (orange). c Schematic diagram of connected hypercubes of different dimensions illustrated schematically as multilayered networks.

The distribution of fitnesses along the hypercube nodes defines the so-called fitness landscape. A fitness landscape is a conceptual model used in evolutionary biology that metaphorically represents the multidimensional space where each point corresponds to a specific genotype and is associated with a quantitative value that represents its fitness. For example, in the most visually appealing two-dimensional representation, the coordinates in the plane represent genotypes, and the elevation over the surface indicates the fitness of that genotype. In simpler terms, a fitness landscape summarizes how well an organism with a particular genotype is adapted to its environment and, e.g., performs in replication. Fitness landscapes can vary in complexity, ranging from simple, smooth landscapes with a single peak representing the optimal genotype to rugged landscapes with multiple peaks and valleys, indicating the presence of different adaptive solutions or evolutionary pathways16,26,27. The shape of the fitness landscape is influenced by several factors, including the genetic architecture of traits, the nature of environmental conditions, and the interactions among different genotypes. Having a precise fitness landscape of viral quasispecies is an extremely challenging problem. For real viruses, fitness landscapes are increasingly viewed as very rugged and dynamic19,28,29,30,31.

Theoretical quasispecies: what has been explored and existing gaps

The population dynamics of quasispecies have been extensively studied since the original contributions by Eigen and Schuster. Several mathematical and computational models have been used to investigate various aspects of viral quasispecies. Here, we discuss the main contributions of quasispecies theory to the field of RNA viruses, highlighting several processes that have not yet been investigated in detail from a theoretical or computational point of view and may be worth exploring. The original Eigen-Schuster quasispecies model is given by the set of differential equations

This mathematical model describes the time change of the fraction of the population of the ith mutant sequence ({x}_{i}) ((i=,1,,…,{n})in x), and (n) being very large. Here ({{f}}_{{j}}) is the replication rate of the jth mutant, ({{Q}}_{{ji}}) is the probability of having a mutation (jto i), and (varOmega (x)={sum }_{j=1}^{n},{f}_{j}{x}_{j}) denotes the average fitness of the population. One key aspect of quasispecies models is that the sequences inhabit a fitness landscape; in this case, each sequence has a given fitness value, which determines its rate of replication. An infecting wild-type (wt) virion can produce an enormous progeny inside the host, giving rise to a large amount of different sequences embedded in a more or less complex fitness landscape. Despite such complexity, the quasispecies model can be explored in a simpler setting, allowing to mathematically characterize phenomena of interest that may also occur in more complex scenarios.

One such useful simplification is to consider a quasispecies formed by only two populations of genomes: the wt and the pool of mutants. This simple model easily illustrates a fundamental consequence of quasispecies theory: the error catastrophe or error threshold. This two-populations model assumes that the quasispecies is embedded in a single-peak fitness landscape3,11,32,33 and the wt sequence, ({x}_{0}) with high fitness ({f}_{0}), produces deleterious mutants that are grouped into an average mutant sequence, ({x}_{1},) all with equal fitness ({f}_{1},<,{f}_{0}). This model also assumes that backward mutations are negligible. This is a first good assumption due to the enormous size of the sequence space. This model can be written taking as variables these two sequence types, with:

Here (mu) is the mutation rate, and (varOmega ({x}_{0},{x}_{1})) is an outflow term given by the average fitness and which keeps a constant population (another unrealistic assumption for real viral quasispecies). This oversimplified model allows the calculation of the error threshold occurring when mutation overcomes the critical value ({mu }_{c}=1-{f_{1}}/{f_{0}}). When ({mu,<,mu }_{c}) the quasispecies is composed by both the wt and mutant sequences, while for ({mu > mu }_{c}) the entire quasispecies is only composed of mutants. In other words, this critical mutation marks a transition between a phase wherein the genetic information carried by the wt sequence is preserved and a phase in which this information is no longer maintained1,32,33,34,35,36. Interestingly, more complex versions of the model that incorporate epistatic fitness landscapes and different modes of genomic replication (e.g., geometric versus stamping machine amplification) still preserve the existence of an error threshold, although its actual value strongly depends on these assumptions and can be even bigger under realistic combinations of parameters (Fig. 2), as we discuss below. For instance, panels (b) and (c) in Fig. 2 show that the critical mutation rate involving a full dominance of mutants is much higher under the stamping machine mode, meaning that the master sequence is preserved in a wider range of mutation rates, as compared with the geometric mode. Moreover, the change in the fitness landscape (how mutations impact a fitness trait, i.e., genomes’ replication speed) has also a big impact on the distribution of the master sequence and the cloud of mutants. A fitness landscape qualitatively mimicking antagonistic epistasis (Fig. 2d) under the geometric replication mode displays an extremely small critical mutation rate. This lower critical value probably arises because mutants close to the master sequence still have good fitness (lower than the master sequence) and thus competition promotes the extinction of the master sequence at ({mu }_{c}simeq 0.02) (Fig. 2e). This critical value changes to ({mu }_{c}simeq 0.15) for the stamping machine replication (Fig. 2f).

Moreover, oversimplifications allowing for mathematical modeling are sometimes meaningful. For instance, research on quasispecies in HCV-infected patients revealed an inverse correlation between viral load and quasispecies complexity7. Such a feature was reproduced with the two-populations model described above using in silico quasispecies evolution33.

The original Eigen-Schuster quasispecies model was built upon several assumptions that might not hold for real viruses. It assumes continuous, well-mixed populations of replicators, constant population, geometric replication, and determinism. During the last decades, considerable efforts have been made to extend the initial quasispecies theory to more realistic scenarios for RNA viruses. Examples comprise the study of other key features of viral quasispecies that are summarized next and which have been investigated separately or in combination. These include finite populations12,37,38, stochastic effects33,38,39, spatially-extended quasispecies38,40,41,42, viral complementation35, and recombination43,44. The investigation of asymmetric modes of replication, identified in RNA viruses either indirectly from mutant distributions45,46,47 or from direct RNA quantification of positive and negative strands during the progress of infection48,49, have been also studied within the quasispecies framework42,50.

Another relevant theoretical result of quasispecies theory is the so-called survival-of-the-flattest effect. This effect is mainly produced because fast replicating genomes that produce low-fitness offspring can be outcompeted by slow replicating genomes with moderate fitness, provided the latter inhabit a region of sequence space characterized by high neutrality and connectivity51,52. This theoretical prediction was first demonstrated in artificial life experiments53 and later described in experiments with competing viroids54 and with VSV55 under mutagenic conditions. This effect was later explored mathematically, and the out-competition of the fit quasispecies by the flat one at an increasing mutation rate was shown to be given by an abrupt transition38. Flat-like quasispecies may underlie failures in resolving chronic infections by antiviral agents, despite the absence of specific inhibitor-resistance substitutions56. Concerning the fitness landscapes, the Swetina-Schuster single-peak one is, of course, an oversimplification of how mutations impact fitness in viral quasispecies. During the last decades, more complex fitness landscapes have been studied for quasispecies27. These include different fitness functions57, dynamic fitness landscapes58,59 and non-linear interactions among mutations, i.e., epistasis9,42,50.

As we have discussed, the original quasispecies theory has been significantly refined over the past decades to better align with real virology. Relevant experimental and clinical results involving RNA viruses have been interpreted through the lens of these theoretical models. Despite this fact, there are still missing ingredients in quasispecies theory that could play a crucial role in the evolutionary dynamics of viruses. For example, some processes, such as RNA viral synthesis or viral protein production and maturation, involve time lags. In this sense, several studies have revealed that the SARS-CoV-2 replication complex has an elongation rate of 150 to 200 nucleotides per second, being more than twice as fast as the poliovirus polymerase complex60. Nucleotide incorporation time, determined by differences at and around viral RNA polymerase catalytic sites, may influence the fidelity of template copying61. In this sense, it is known that time lags can profoundly affect the dynamics of nonlinear systems, causing self-sustained oscillations and chaos62. Also, during their intracellular phase, viruses synthesize distinct molecules, constructing viral factories for genome replication and encapsidation. The central element of these factories is the replication organelle (RO), where viral replication complexes produce multiple copies of the viral genome. Viral factories often consist of remodeled cell membranes with functional compartments for replication, assembly, and egress, and they frequently recruit other cellular elements like mitochondria and the cytoskeleton, which interact with the RO. Unlike DNA viruses, almost all RNA viruses form factories exclusively in the cytoplasm63,64. For instance, HCV induces remodeling of reticulum endoplasmatic membranes forming double-membraned vesicles, and later on, it induces the formation of multi-membrane vesicles that are composed of several concentric membrane bilayers. These membranous rearrangements are produced by the action of viral nonstructural proteins. Hence, the process of virus genome amplification can be highly compartmentalized inside the cell and possibly also induce time lags in viral replication and virion assembly.

For RNA viruses, especially those infecting plants, replication processes may exhibit periodic fluctuations at the within-tissue or within-host levels across different time scales, primarily due to temperature changes65. Additionally, the mammalian brain possesses an endogenous central circadian clock that regulates both central and peripheral cellular activities. At the molecular level, this day-night cycle triggers the expression of upstream and downstream transcription factors that affect the immune system and modulate the severity of viral infections over time. The role of circadian systems in regulating viral infections and the host response to viruses is thus of great clinical importance66, and thus fluctuating parameters may be included in theoretical quasispecies investigations.

Another unexplored process in quasispecies theory is how the evolutionary dynamics of quasispecies at the within-cell/within-host levels scale up to the population-epidemiological levels. This question, which we discuss below, can be addressed by developing multi-scale models including the rapid quasispecies evolution (fast dynamics) and the impact of the continuous synthesis of heterogeneous mutants at a population scale (slow dynamics). The mathematical results on slow-fast systems may be thus relevant to tackle this problem. In this sense, the connection of scales in virology is extremely important to understand virus pathogenesis and potential zoonoses and epidemic spread among different hosts36. This subject can be further explored combining dynamical systems theory with complex networks theory.

The limits of predictability of quasispecies are also an extremely challenging and open problem in virology. That is, how the dynamical population structure of the quasispecies may impact disease outbreaks and the emergence of new variants with epidemic and pandemic potential (see Section on Impact of quasispecies populations in emerging viral diseases below).

Quasispecies and RNA viruses: genomic heterogeneity, adaptation and clinical implications of genetic information thresholds

Initial experimental evidence of viral quasispecies dynamics involved studies mainly with bacteriophage Qβ, VSV, FMDV, or LCMV (reviewed in ref. 10). These experiments have robustly confirmed high mutation rates during genome replication, the heterogeneity of viral populations, fitness variations among biological clones, rapid changes in sequence space occupation, and limited tolerance to increased error rates, to cite a few. The early studies with bacteriophage Qβ by Weissmann et al. were carried out simultaneously with the development of quasispecies theory by Eigen and Schuster in the 1970s. In the 1980s and 1990s, the primary approach was to compare genomic sequences of molecular or biological clones from natural viral isolates or viral populations subjected to various experimental evolution designs. The advent of ultra-deep sequencing techniques greatly broadened the capacity to probe the complexity and dynamics of viral quasispecies. The extended capacity to probe into the complexity and dynamics of viral quasispecies afforded by ultra-deep sequencing is exemplified by results on HCV7,67 and, more recently, in SARS-CoV-2 displaying multitudes of low-frequency mutations in isolates of the virus, some of them endowed with functional relevance68,69,70.

During recent years, the development of new high-throughput sequencing techniques (e.g., Cir-Seq) along with novel bioinformatic algorithms have shown the relevance of an abundant component of viral quasispecies that was previously largely ignored: the defective viral genomes (DVGs)71,72,73,74. Broadly speaking, DVGs are nonstandard genomes generated during error-prone replication that contain deletions, insertions, duplications, inversions, and potential hypermutated viral genomes contributed by cellular editing activities. These major-effect mutations render genomes unable to self-replicate, and coinfection with a wt (also dubbed helper) virus is needed for the defective genomes to persist in the population. Several recent studies have described the temporal dynamics of DVGs during the course of infection for several viruses, including poliovirus (PV) and dengue virus (DENV)75, influenza A virus (IAV)76, SARS-CoV-277 and other betacoronaviruses74. Consistently, these studies show that some DVGs are pervasively maintained in the viral population in cell cultures but also in patients, suggesting a possible selective role. For instance, deletions affecting the receptor binding domain and the S1/S2 cleavage site in SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant may have increased host cell ACE2 receptor recognition, thus enhancing the infection and allowing this variant to become dominant78. Indeed, it has been suggested that DVGs might confer some advantage to viruses, such as serving as reservoirs of genetic variability, decoys for immune responses, regulators of translational shut-down, or mediators of persistent infections72.

A particularly notable type of DVG due to its structural and GC content requirements is the copy-back and snap-back (cb/sb) variants, which consist of small RNA molecules with a hairpin-loop structure created by template-switching from positive to negative templates during replication.

As we have mentioned, an increase in population mutational load should concomitantly result in a decrease in the average population fitness as most mutations with phenotypic effects are deleterious or lethal20,21,22,23,24,25,79. Given this, and together with the aforementioned prediction of the existence of a critical mutation rate beyond which the population enters the error catastrophe regime1,4, innovative antiviral strategies have been proposed aiming to push down replication fidelity and forcing the viral population to cross the error threshold. Nucleotide analogs can act as antiviral agents, and one of their mechanisms of activity is the elevation of the viral polymerase error rate beyond the maximum value compatible with maintenance of viral infectivity79,80,81. This strategy adds to others intended to minimize selection of escape mutants, for example, sequential antiviral administrations, use of antiviral agents that target cellular functions which are needed for completion of the virus infectious cycle, combination of immunotherapy with chemotherapy, use of antiviral agents that enhance the innate immune response, etc. These different approaches have been investigated experimentally and with theoretical models that computed the risk of antiviral escape and means to counteract treatment failures82,83,84,85 (see also ref. 86 and references quoted therein).

Quasispecies complexity: from the hypercube to the ultracube

In the study of viral evolution and coevolution, hypercubes provide a useful conceptual framework for comprehending the sequence space of viral genomes and its eco-evo/coevolutionary dynamics4,27,87. This sequence space is a mathematical multidimensional construct where each dimension corresponds to a nucleotide position within the viral genome (Figs. 2 and 3a). A hypercube, in particular, is a discrete geometric representation of this space, with vertices representing every possible sequence configuration in which a viral genome of length L can exist. Each vertex is connected to adjacent vertices by edges that signify single nucleotide changes, illustrating the potential mutational pathways a virus can traverse while retaining the same length. This model effectively visualizes the extensive diversity and evolutionary potential of viral populations. The structure of the hypercube allows researchers to analyze the distribution and dynamics of viral quasispecies within this space, providing valuable insights into how viruses adapt to environmental pressures and develop resistance to antiviral treatments. The foundational works of Eigen and Schuster1,2 were instrumental in introducing the concepts of sequence space and hypercubes within the framework of quasispecies theory, offering a mathematical basis for understanding the evolutionary landscape of viruses3. However, we postulate that viral quasispecies may be embedded within more complex and entangled sequence spaces, including the full spectrum of mutant sequences together with, e.g., subgenomic sequences and DVGs. These length variants may form other subpopulations of clouds of mutants spanning lower- or higher-dimensional hypercubes arising from the full-genome sequence space, thus being connected through deletions or insertions. Hence, a more realistic geometric space for viruses may include connected hypercubes of different dimensions: we call these sequence spaces, in which a given node can represent a hypercube itself, as ultracubes (Fig. 3b). This view enlarges the size of the sequence space beyond the single-point mutation hypercube dimension. As for the hypercube, a quasispecies may not span all this sequence space but be located on some specific regions of this ultracube in a mutation/recombination/deletion/insertion-selection balance.

Multilayer models for multi-scale virus dynamics: integrating quasispecies into virus epidemiology and ecology

A new area of complex networks theory that has been quickly developing over the last decade is the study of multilayer networks. Each layer contains nodes connected by intralayer edges that describe rules of interactions between the nodes for this particular layer. In addition, dependencies across layers are represented by interlayer edges. It is straightforward to place and visualize viruses into a multilayer; for illustrative purposes, let us discuss here a simple 3-layer case. The bottom layer would represent the quasispecies generated within a single infected individual. At this level, the ultracube (Fig. 3b) would be an appropriate representation. The equations describing the dynamics at this bottom level could be those described in the previous sections incorporating mutants of different nature. A middle layer would represent local host populations. At this level, each node corresponds to a particular host, and the edges represent the contact network among the hosts that determines transmission dynamics. The equations governing the virus’ dynamics at this intermediate level could be the well-known SIR epidemiological model, and the network can show any topology, such as scale-free88. The interlayer edges connecting the bottom and the middle layers represent the probability that a given viral genotype is actually present in each infected host, which indeed depends on the replicative advantage at the bottom level and the mutation rate. Coinfections are allowed (two interlayer edges pointing towards the same individual). The upper layer represents the epidemiological level. In this layer, nodes represent, e.g., communities, whereas edges represent the connectivity between these communities (e.g., airport traffic connections, vector flights, pollen and seed dispersal, etc.). The dynamics at this level can be modeled using phylogeography tools. The interlayer edges connecting the middle and the upper layers would represent the probability that an infected individual will move from one community to another.

This multilayer representation may allows to study not only the dynamics at each layer but also the entire multilayer system and infer properties such as multilayer modularity, robustness to perturbation or phase transitions. The intra-host evolutionary dynamics (bottom layer) has been modeled in connection with epidemic spread (upper layer)89. Viral genotypes closely connected in the quasispecies bottom layer may be found in individuals in the middle layer that also form a transmission cluster (or module). For instance, ecological multilayer networks for plant-aphid and plant-aphid-parasitoids90 show nontrivial stability properties that result in quantitative predictions about the persistence or extinction probabilities that would not be shown up by other modeling approaches91. Information between nodes in a particular layer can be transmitted via two different paths: those involving only intralayer edges and those involving both intra- and interlayer edges. This means that catastrophic failures in a particular layer can easily be transmitted to the rest of layers92,93. An example of catastrophic failures across levels in biomedicine is the understanding of pathological conditions via the network cell organization into genes, proteins and metabolites. Cell malfunctions are rarely the result of one of these three levels. Rather, they result from multiple interactions at the three levels. This view reinforces the prospects for personalized medicine whose impact in viral disease control is still to be investigated. This, and other examples in different domains of science, of the consequences of inter-layer interactions are described in ref. 93. The epidemic spread of infectious diseases in multilayer networks has received some attention94,95,96,97. Examples are: (i) In particular, a topic that has been studied is the interaction between two genetic variants of the same virus, showing that coexistence or displacement of the less fit variant depends on the connectivity between layers96,98,99,100. (ii) In multilayer networks, the disease can spread through multiple channels or layers simultaneously, which affects the overall dynamics. For instance, a disease might spread rapidly in one layer (e.g., in the example of vector-borne viral diseases, within the vertebrate host population) and more slowly in another (e.g., in the same example, within the insect population)91,99. The coupling between these layers can either enhance or inhibit the spread, depending on factors like the strength of connections between layers or the level of interaction between them. (iii) In classic epidemiological SIR or SEIR models, there are often R0 thresholds that determine whether an epidemic will occur. In multilayer networks, these thresholds became more complex. The disease might die out in one layer (e.g., in our example of the vector-borne virus, from the vertebrate population) but continue spreading in another (e.g., in the mosquito reservoir), or it might require a critical level of interaction across layers before an epidemic can fully develop88. (iv) Multilayer networks naturally introduce heterogeneity into the system. Different individuals or nodes may have different degrees of connectivity in each layer, leading to varied exposure risks. For example, a person who is highly connected in one layer (e.g., traveling overseas a lot) but less connected in another (e.g., in its home local community) may play a unique role in disease transmission97,101. Finally, (v) fitness values are environment- and population context-dependent. Positive correlation of fitness values across the intra-host and the inter-host (transmission) scales can facilitate a successful pathogen emergence102. A stochastic model further determined that a wide transmission bottleneck can help the emergence, unless pathogens exhibit cross-scale selective conflicts103.

When multiple variants are spreading in a host scale-free network and competing for hosts, they obviously influence each other’s dynamics. In such a situation, for example, the derived epidemic threshold for each variant is substantially different than predicted using monolayer simple coinfection models. Indeed, two new thresholds arise from these models99: (i1) the survival threshold determines a continuous phase transition from extinction to existence during competition between both variants. (ii2) The absolute-dominance threshold denotes the critical point where one of the variants fully outcompetes the other. Between these two thresholds, coexistence emerges as a property of the interconnected structure of the multilayer. The incorporation of quasispecies models within multilayer networks may allow considering the impact of the microevolutionary dynamics of viral quasispecies at a multi-scale level. In this sense, continuously generated variants may impact at a populational level (epidemiological scale), and phenomena such as the error threshold could determine transitions in upper layers. A discussion on the multi-scale nature of viruses is discussed in ref. 36.

Impact of quasispecies populations in emerging viral diseases

The emergence of viral disease is an unpredictable event since it is the result of several interconnected factors: the adaptive potential of viruses circulating in different host species, environmental modifications, or political and sociological circumstances, among others. These factors can affect virus traffic and facilitate encounters with potential new hosts104,105,106. Viral emergence can be regarded as a facet of complex biological behavior since its occurrence cannot be anticipated by the sum contribution of the multiple underlying factors36,107,108. Since quasispecies enhances viral adaptability and microbial adaptability is one of thirteen factors involved in transmissible disease emergence106, it is sometimes assumed that there is a direct connection between quasispecies and viral disease emergence. A direct connection is difficult to prove experimentally. However, several studies have shown that the presence of cell tropism and host range mutants in mutant spectra (or the presence of an ample mutant repertoire) mediated the adaptation of a virus to a different host species. Examples include parvoviruses, coxsackievirus B and foot-and-mouth disease virus (reviewed in ref. 109). In this scenario, the production of mutant viruses at high frequency in immunocompromised individuals [described for several viruses109 including SARS-CoV-2110,111 may represent an additional supply of potential host range modifications. All the genotypic complexity portrayed by the ultracube connections (Fig. 3b) adds to the lottery of which variants (and when) they may come into contact with a susceptible individual of a different host species, to initiate an infection and to produce sufficient transmissible progeny to achieve the status of emergent disease.

John Holland and colleagues were the first to point out a number of medical implications of a highly dynamic RNA world coexisting with a relatively more static DNA-based cellular biosphere112. They underlined high mutation rates as a source of atypical viral forms capable of invading new tissues and organs, to establishing persistent or inapparent infections, or being to be selected in response to medical interventions. These facets of viral dynamics have been amply documented in the 1940s that have followed their prescient publication. Joshua Lederberg warned of the human vulnerability in the face of the adaptive potential of RNA viruses: “Abundant sources of genetic variation exist for viruses to learn new tricks, not necessarily confined to what happens routinely or even frequently”113. In May 2003, the World Health Organization released a report titled “SARS: Status of the outbreak and lessons for the immediate future”114. Work on population heterogeneity and quasispecies dynamics of the emergent SARS-CoV-2 has confirmed coronaviruses as a genetically and functionally highly variable virus group, and as a threat to produce future emerging diseases31.

Future challenges in experimental and clinical quasispecies

As often happens in science, new techniques pose new questions. The availability of deep sequencing methodology to probe into the composition of virus populations has opened new questions, in addition to solving old ones such as the definitive confirmation that mutant spectra are the biological reality of viral populations, so far without documented exceptions. Among the new challenges are: (i) capturing the depth of minority genomes that until now have escaped detection; (ii) how they feed the dominant ones, be them viable or defective; (iii) how the latter modulate behavior of the ensemble; (iv) which is the time frame in which minority subpopulations can be replaced by others, relative to the time required for selective forces (metabolic modifications, signal effectors, antibodies, drugs, etc.) to reach the extracellular and intracellular environments or even individual viral factories; (v) what is the extent of heterogeneity within individual cells; and (vi) capacity of mutant spectrum composition to inform of long-term evolutionary events. These are but some of many highly relevant questions. What is at stake is to better understand viruses, the diseases they produce, and the means to combat them. In short, a challenge is to shift from a consensus sequence-centered understanding of evolution into a mutant spectrum-centered understanding of evolution, and harmonizing the conclusions drawn from both.

Therapies based on the error catastrophe concept have been brought forward81,115. Maintenance of inheritable genetic information conditioned to a limitation in error introduction has also been documented with catalytic ribozymes116. Lethal mutagenesis approaches exploit the intrinsic balance between mutation rates and viral viability, offering a promising avenue for combating viral infections. As a difference from the error threshold, which causes a shift in the sequence space, i.e., the master sequence is replaced by the mutant swarm, lethal mutagenesis involves virus extinctions32. Virus extinction by lethal mutagenesis has been documented with several RNA viruses and mutagenic base and nucleoside analogs, which are licensed for clinical use (reviewed in ref. 81). These include, the pioneering works with HIV-180,117, PV118, FMDV119,120, LCMV121,122, and HCV123,124 in cell cultures. Several base and nucleoside purine and pyrimidine analogs have contributed to the research and development of lethal mutagenesis of RNA viruses. Some of them have been in clinical use for years or decades, notably ribavirin and favipiravir. They have been administered either as Food and Drug Administration-approved agents for some specific diseases, or as off-label use for other diseases. Ribavirin has been extensively applied to treat respiratory syncytial virus infections of infants, and as part of combination therapies for chronic hepatitis C, or as off-label treatment of arenavirus-associated hemorrhagic disease. Favipiravir is used as anti-viral influenza in Japan. Regarding their mechanism of activity, the base or nucleoside analogs (or their pro-drugs) are intracellularly converted into their corresponding nucleoside-triphosphate forms, which are the active mutagenic agents during viral RNA synthesis. They are incorporated by the viral RNA-dependent RNA-polymerases into nascent RNA in competition with the standard purine or pyrimidine nucleotides, giving rise to mutated viral RNA progeny. Indications that lethal mutagenesis is operating include an increase of viral mutation frequency, decrease of specific infectivity and invariance of the consensus sequence of the population. Viral extinction can be achieved either by lethal defection ─which entails moderate mutagenic activity and interference by a class of defective genomes termed defectors─ or by overt lethality when the excess mutations is incompatible with virus infectivity125. Analogs whose antiviral activity is exerted partly by lethal mutagenesis have proven effective in producing significant viral load reductions or the extinction of at least fifteen RNA viruses in cell culture or in vivo (concept and specific examples reviewed in ref. 81).

More recently, the pyrimidine analog molnupiravir has been used as an anti-COVID-19 agent. It adds to the delayed chain terminator remdesivir (and its combinations with fluoexetine, itraconazole or other drugs) as first-line treatments against COVID-19. Several potential problems have been identified associated with the use of mutagenic analogs in general and with molnupiravir for COVID-19 in particular. They include side-effects on the host cells and organisms by the analogs or their catabolic products, selection of viral mutants resistant to the analogs, or selection of additional mutants when the treatment is only partially effective and analog-produced mutants retain sufficient replicative and epidemiological fitness. The latter scenario has been suggested for molnupiravir treatments as the possible origin of SARS-CoV-2 mutants when the drug is administered to immunocompromised patients that exhibited a debilitated immune response, thus allowing large replicating viral loads126,127. Virological, biochemical and structural studies suggest that lethal mutagenesis is, at least in part, the mechanism of some antiviral agents currently used to treat COVID-19115,128,129,130.

Synergistic antiviral combinations that include one or two lethal mutagens (a strategy termed synergistic lethal mutagenesis) constitute a promising avenue for the treatment of COVID-19, extensible to other emergent RNA viral infections115. Additionally, lethal defection, characterized by the extinction of viral populations due to the emergence of DVGs, has been observed for LCMV in cell cultures125. For this virus, two extinction pathways have been identified: one at high mutagen concentrations, resulting in the complete loss of infectivity and replication ability of the quasispecies, and another at lower mutagen concentrations, where replication persists while the infective class becomes extinct due to the presence of defectors.

For a long time, the aforementioned cb/sb mutants have been known for their negative impact on virus accumulation, as they retain the replication signals of both polarities and have a replication advantage owed to their very short genomes. In recent years, the antiviral efficiency of synthetic cb/sb, known as therapeutic interfering particles (TIPs), has been proven against SARS-CoV-2 in animal models. These antiviral effects have involved a decrease in virulence and milder edema symptomatologies131 as well as a decreased viral transmission132 in hamsters. Thus, the continuous expansion of theoretical quasispecies concepts, and their scrutiny with viral experimental systems, now reinforced with the new tools of ultra-deep sequencing, is paving the way towards innovations for the control of highly heterogeneous and dynamic cellular pathogens.

Responses