R-pyocins as targeted antimicrobials against Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Introduction

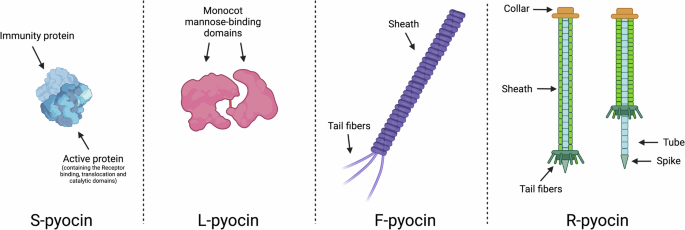

In 1945, Edwin Hays and colleagues first described antibiotic substances derived from Pseudomonas pyocyanea, and 9 years later, François Jacob deemed these antibiotics as “pyocines”1,2. Today, “pyocins” refer to the narrow-spectrum bacteriocins produced by P. pyocyanea, now known as P. aeruginosa2,3. The pyocins produced by P. aeruginosa have since been described and categorized into several types referred to as S-, L-, F-, and R-pyocins (Fig. 1). Each subtype of pyocin differs in physical and chemical properties, export mechanisms, and mode of action, though a strain may possess the genetic determinants to produce any combination of, or all types of, pyocin4,5,6,7. S-pyocins are single proteins that have an accompanying immunity protein in producing strains; when active, S-pyocins include a receptor-binding domain, translocation domains, and a catalytic domain, such as for DNAse activity8. In contrast to S-pyocins, R-pyocins and F-pyocins both resemble phage tails without DNA-containing capsid heads5,6,9. L-pyocins, or lectin-like pyocins, are narrow-spectrum antibacterial proteins composed of two tandemly organized monocot mannose-binding lectin (MMBL) domains and are primarily found in many species of plant-associated Pseudomonads10,11. F-pyocins have a flexuous structure resembling a filamentous, non-contractile bacteriophage and are similar to phage formerly of the Siphoviridae family5,6,9,12,13,14. Six subtypes of F-pyocin have been described as determined by their killing spectrum (or 11 subtypes distinct by sequence) however, little is known of their mechanism of action beyond that they are thought to bind to the lipopolysaccharide (LPS), form a channel through the membrane, and disrupt respiration9,12,14,15. R-pyocins—the contractile, phage tail-like bacteriocins of P. aeruginosa—specifically are of interest as alternative antimicrobial therapies due to their potent anti-pseudomonal activity, known receptors, and well-described mechanism of action. In this review, we focus on R-pyocins due to their promising characteristics as antimicrobial agents, along with the need for a better understanding of their activity during infection.

The bacteriocins of P. aeruginosa are described as S-, L-, F-, and R-pyocins. S-pyocins are soluble enzymatic-immunity protein complexes, and L-pyocins are complexes of two tandem lectin domains. F- and R-pyocins resemble phage tails with sheaths or tubes, and tail fibers to recognize target cells. R-pyocins consist of a contractile sheath, with a spiked core to facilitate the puncture of a target cell membrane.

While phage therapy has recently regained recognition as a developing alternative to traditional antibiotics due to its specificity and ability to tackle antibiotic-resistant bacteria, R-pyocins offer similar, if not enhanced, benefits with fewer complications16,17. Unlike phages, R-pyocins do not replicate within a host bacterium5,6,18,19. This non-replicative nature makes dosing and treatment control more predictable, as R-pyocins remain in a fixed concentration rather than multiplying within the target organism. This controlled replication also prevents unintended ecological impacts on the host microbiome and minimizes the risk of excessive bacterial lysis that can lead to the release of endotoxins, a potential complication in phage therapy17. R-pyocins are also inherently selective and typically only target specific bacterial strains, much like phages. However, phages can engage in horizontal gene transfer, potentially spreading virulence and/or antibiotic resistance genes among bacterial populations20. R-pyocins, lacking a DNA-containing capsid, cannot facilitate such gene transfer21. This absence of gene transfer potential makes R-pyocins a safer option for therapy, reducing the risk of unforeseen genetic consequences in treated bacterial populations. Another benefit of lacking the DNA-containing capsid is that R-pyocins are structurally more stable than phages, whose fragile capsids are prone to damage in preparation, storage and during delivery. This stability suggests that R-pyocins could have a simpler formulation process and potentially longer shelf life, making them practical for broader clinical deployment and storage in diverse healthcare settings. As they do not infect target cells with nucleic acids, to our knowledge, R-pyocins are not affected by anti-phage CRISPR systems, a critical consideration for alternative therapeutics in evolved strains with a number of unknown CRISPR systems22. Much like phages, R-pyocins can also be engineered to modify their host range or improve binding affinity to specific bacterial receptors23,24,25. Bioengineering efforts on R-pyocins have led to enhanced variants with expanded targeting capabilities, making them potentially adaptable for clinical scenarios involving mixed-species infections or infections caused by hard-to-target bacterial isolates. In this review, we delve into the therapeutic potential of R-pyocins by examining their unique structure and adaptability while also exploring current delivery methods and highlighting how they address limitations associated with phage therapy.

Physical properties of R-pyocins

Structure of an R-pyocin

R-pyocins are antimicrobial particles similar in structure to the tails of phages formerly classified as Myoviridae but lack the DNA-containing capsid of typical, replicating phages4,7,13,18,19,26,27. R-pyocin particles consist of a polymer tube core surrounded by a contractile sheath; a pointed, iron-tipped tail-spike is attached to the core along with a baseplate and tail fibers (Fig. 1)5,19,21,28,29,30,31. While the majority of the structural and lytic genes are highly conserved across P. aeruginosa strains, the tail fiber and the chaperone genes are notably diverse32. The tail fibers serve to recognize and bind to the receptor(s) on target cells and are thus the determinant of the spectrum of killing. As the C-terminal sequences of the tail fibers, corresponding to a “foot” of the fiber, differ among strains, there have been five subtypes of R-pyocin described to date denoted R1-55,26,32,33. Subtypes R2-4 have a similar amino acid sequence and overlapping killing spectra, and so are often categorized as a single, broad subtype under the R2 type5,6,25,26. Unlike with S-pyocins, in which a P. aeruginosa strain may carry genes for multiple S-pyocin subtypes, a strain only carries the genes to produce one subtype of R-pyocin5,6. It is important to note, however, that an in-depth crystal structure analysis of the R1 and R2 type tail fibers revealed two knob-like domains (which are commonly found in saccharide-binding tail fibers and tail spikes) and a C-terminal lectin-like domain (which is also involved in binding to the sugar portion of the LPS)28,31. These results suggest that both the secondary knob-like domain (referred to as Knob2) and the C-terminal lectin-binding domain may both play a role in binding to target cells, and diversity in the sequences of both the knob-like and C-terminal domains across R-pyocin subtypes suggests there may also be further subdivision of the known R1-5 subtypes, determined by differences in the Knob2 domain28.

Size and charge

According to atomic models of the R-pyocin in pre- and post-contractile states, we estimate the approximate size of an R-pyocin particle to be approximately 11.1 Mda29,30. Purified R-pyocin preparations can be visualized using standard denaturation methods and SDS-page gel, where major components such as the tube protein (~18 kDa) and tail fiber (~72 kDa) can be identified23,24,29,30. While we can estimate the size of an assembled R-pyocin particle and denatured R-pyocin components, the charge of an assembled particle remains unknown. Contractile-tailed phage generally contain a positively charged inner tube to bind DNA, thus the DNA contributes to an overall negative net charge of the phage particle34. The current R-pyocin atomic model determined by cryo-EM found R-pyocin particles have a negative inner tube (they do not bind DNA)29,34. It is likely that R-pyocins have a negative net charge as well, with the negatively charged tube perhaps providing the particle stability and a similar isoelectric point to phages despite the lack of negatively charged, bound nucleic acid29,30.

The chaperone protein

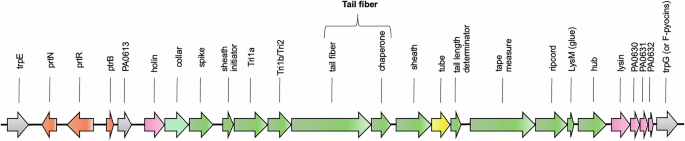

The assembly of R-pyocins requires a specific chaperone protein that is crucial for the proper folding and assembly of the tail fiber25,31. The chaperone protein for the R2-type pyocin is encoded by the PAO1 gene PA0621 (Fig. 2)5,35. Chaperone genes are typically located immediately downstream of the tail fiber gene (locus PA0620 in PAO1) with an 8-nucleotide overlap, indicating tight coupling of their expression5,35. While the chaperone does not directly determine binding specificity, it is essential for the correct assembly of the tail fiber, which is the primary determinant of the R-pyocin bactericidal spectrum. Chaperones show specificity for their cognate tail fibers (which determines binding specificity and R-pyocin type), particularly in the C-terminal region13,25. For instance, R1 and R5 pyocins, with divergent tail fibers, require their own chaperones for optimal assembly, even when expressed in a heterologous R-pyocin background13,25: The importance of chaperone specificity was demonstrated when expressing R1 prf15 (tail fiber gene) in trans in PAO1 Δprf15; optimal activity required co-expression of its cognate chaperone (R1 prf16). Similarly, R5 Δprf15 produced practically no active pyocin particles unless the R5 chaperone gene (R5 prf16) was co-expressed. This chaperone specificity is a critical consideration when engineering novel R-pyocins with chimeric or non-native tail fibers13. Williams et al. showed that when creating a novel R-pyocin with a P. aeruginosa PS17 phage tail fiber (pyR2-PS17), active particles were only produced when the PS17 chaperone gene was co-expressed. Likewise, chimeric tail fibers made from R2 pyocin and P2 phage components required co-expression of the P2 chaperone (gene G) to form active R-pyocins. Notably, the availability of the Prf16 chaperone appears to be a limiting factor in wild-type R2 pyocin production, as co-expression of R2 Prf15 and Prf16 in trans resulted in consistently greater yield (2 to 5 times) of R2 pyocin compared to when the only source of Prf16 was genomic25. This chaperone specificity is a critical consideration when engineering novel R-pyocins with chimeric or non-native tail fibers for targeted antibacterial applications.

R-pyocin genes are found in a single region on the P. aeruginosa chromosome as an operon between trpE and trpG, either as only the R-pyocin loci or as an R-pyocin and F-pyocin loci. When both the R-pyocin and F-pyocin genes are present, they share the regulatory genes (in orange) and lytic genes (in pink) flanking the R-pyocin structural genes (in green). The structural genes of the R-pyocin loci are highly conserved across strains with the exceptions of the tail fiber and the chaperone genes, which are involved in receptor specificity and subtype differentiation. Genes are labeled as PAO1 loci or gene names.

R-pyocin regulation

Similar to prophages, R-pyocin genes are located on the P. aeruginosa chromosome, often (but not always) with F-pyocin genes directly downstream36. Three types of R- or F-type pyocin loci are found in P. aeruginosa, encoding either just R-type pyocins, R- and F-type pyocins, or just F-type pyocins14. All three types of loci share the same regulatory genes and lysis genes and are invariably found between trpE and trpG on the P. aeruginosa chromosome13,14. While in P. aeruginosa, there is only a single R-pyocin locus of conserved genes found in the same location in every strain, other species of Pseudomonads have been found to carry multiple R-type tailocin loci, which may be found in variable locations throughout the genome37,38,39,40.

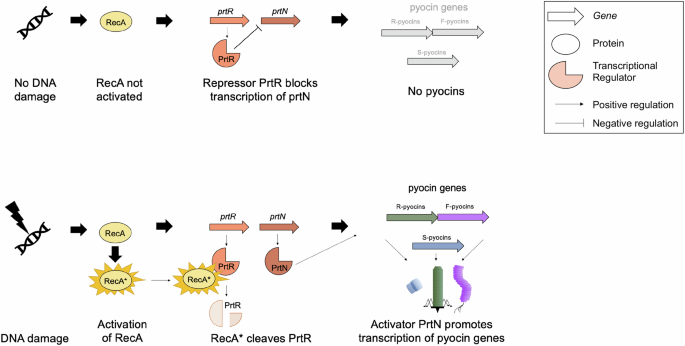

R-pyocin production is known to be induced by the SOS response via DNA-damaging agents, including UV radiation, mitomycin C, ciprofloxacin, and oxidative stress35,36,41,42,43,44,45. Several transcription factors of P. aeruginosa have been found to play a role in regulating R-pyocin production and assembly under SOS conditions, including PrtR and PrtN (Fig. 3). R-pyocins are known to be regulated under two mechanisms: RecA-dependent and RecA-independent18,36,46,47. The current model of RecA-dependent R-pyocin regulation predicts that following detection of DNA damage, activated RecA (known as RecA*) cleaves the negative repressor PrtR, allowing PrtN to activate expression of R-pyocin genes36.

Following the detection of DNA damage, activated RecA becomes RecA* and cleaves the negative repressor PrtR. The cleavage of PrtR allows PrtN to activate the expression of pyocin genes, including the R-pyocin genes.

While not indicated in the figure, RecA-independent regulation of R-pyocins has been shown to occur in the absence of a tyrosine recombinase (XerC); however, the induction is still dependent on the PrtN positive regulator; the role of XerC (if any) in RecA-dependent regulation remains unknown46,47. This RecA-independent mechanism allows P. aeruginosa to modulate its pyocin production in response to specific environmental cues or genetic conditions outside of DNA damage and the traditionally understood SOS response. It is important to note, that under both RecA-dependent and independent pathways, the producing cells lyse to release R-pyocins into the environment43,48,49,50.

Mechanism of action

R-pyocins kill bacteria through a stepwise membrane-targeting mechanism that parallels, but distinctly differs from, bacteriophage tail contraction29,30. Initial binding occurs when the R-pyocin tail fibers recognize specific monosaccharide residues in the outer core polysaccharide of the bacterial LPS28,32. Upon receptor binding, the baseplate undergoes a dramatic conformational change from hexagonal to star-shaped, which triggers sheath contraction. The contracted sheath drives the inner tube through the outer membrane of the target cell. Notably, R-pyocins possess a negatively charged inner tube surface, contrasting with the neutral or positively charged surfaces of phage tails that transport DNA, suggesting specialization for ion conduction28,29,30.

The path to bacterial cell death involves sequential disruption of membrane energetics. Like T4 phage tails, after penetrating the outer membrane and degrading the peptidoglycan layer via the lysozyme activity of the N-terminus of the dissociated spike protein, the R-pyocin tube is thought to approach but not physically puncture the inner membrane30,51. Cryo-electron microscopy of T4 phage infection shows the inner membrane undergoes significant remodeling, bulging outward to meet the tail tip51. R-pyocins contain many minimalistic homologs to T4 structural proteins, including the baseplate hub protein and a tape measure protein, both of which are likely involved in a similar formation of a transmembrane channel into the cytoplasm. This interaction leads to the formation of an ion-conducting channel that dissipates the cell’s proton motive force by depolarizing the membrane potential from approximately −90mV to 0 mV52. This loss of membrane potential disrupts active transport systems and cellular energetics, ultimately causing cell death. This killing mechanism underlies several key advantages of R-pyocins as therapeutics: their action is rapid and independent of cellular metabolism, they maintain structural stability due to their lack of fragile capsids (compared to phages), and their ion channel-forming ability provides a distinct mechanism from traditional antibiotics. The specific targeting through defined LPS receptors combined with membrane depolarization makes them particularly attractive as precision antimicrobial agents for treating antibiotic-resistant infections.

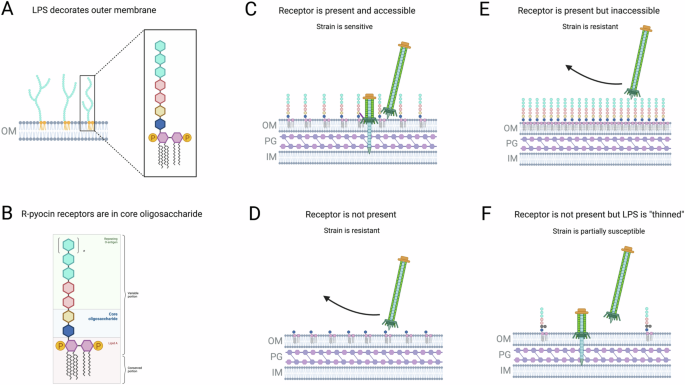

Work thus far has shown that the LPS may act as both a shield and the receptor for R-pyocins, through several scenarios (Fig. 4)32,53. As the receptor residues on the LPS reside in the inner core oligosaccharide, both the presence and accessibility of the receptor play a role in R-pyocin susceptibility. If the receptor is both present and accessible, then the strain will be R-pyocin sensitive; however, it has also been suggested that R-pyocins may be able to kill any strain if the cell envelope is accessible enough to penetrate (i.e., the LPS is “thinned” or displays reduced packing density)53. Strains may be resistant to R-pyocins if the receptor is not present, such as in LPS core mutant stains, or if the LPS molecules are very dense and tightly packed, blocking R-pyocin access to the receptor residues. It is important to note that R-pyocins do not have corresponding immunity proteins; only LPS composition and packing density have been shown to impact R-pyocin-mediated killing; however, there may be other mechanisms at play, yet to be discovered6,32,53,54.

The LPS is displayed on the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria (A) and is composed of a variable O-antigen chain, core oligosaccharides, and lipid A (B). R-pyocins recognize specific residues of the core oligosaccharide and are able to kill cells with the receptor is both present and accessible (C). A strain may be R-pyocin resistant if the receptor is inaccessible (E) or is missing due to a mutation (D). One theory suggests that even if a receptor is not present, R-pyocin may kill a cell if the LPS shield is “thinned” enough that the cell envelope is accessible (F). Adapted from Carim et al.53.

Receptor specificity

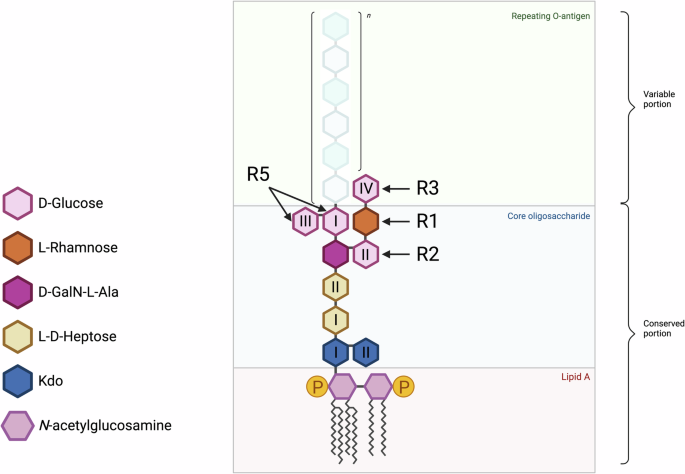

An important facet of using R-pyocins as antimicrobials is that the receptors of each of the R-pyocin subtypes are known and have been described32,52,55,56. In contrast, many phages that have already been used and approved as alternative therapies for use in patients do not have known receptors, nor are their binding mechanisms understood17,57,58. R-pyocins function as antimicrobials by recognizing a specific residue of the LPS on target bacteria, then contracting and puncturing the cell envelope; this causes a depolarization of the membrane and inhibits active transport28,30,59. R-pyocin type is determined by the sequence of the C-terminal region of the tail fiber gene, corresponding to the structural “foot” of the tail fiber; this sequence influences receptor recognition and binding of each of the R-pyocin subtypes. Various monosaccharide residues on the outer core of the LPS have been attributed to serving as the receptor for each of the subtypes of R-pyocin, however the receptor for R4-pyocins is still unresolved (Fig. 5)28,43,48,55,56.

The outer core of an uncapped LPS of P. aeruginosa exposing D-glucose (GlcI-GlcIV) residues, the receptors recognized by each of the five subtypes of R-pyocin. Roman numerals are assigned to glucose units based on their positions and connectivity in the primary structure of the O-antigen. The inner core consists of two residues of 3‑deoxy-α-D-manno-octulosonic acid (Kdo) and two residues of L-glycero-D-manno-heptose (L-D-Hep). The outer core consists of one residue of D-galactosamine (GalN) with alanyl (Ala) group (D-GalN-L-Ala), one L- Rhamnose, and three to four D-glucose residues. The R-pyocin subtypes have been determined to bind to the D-glucose residues of the outer core. The D-glucose residue utilized by the R4-pyocin remains unresolved. The antigenic, repeating O-antigen unit used for determining strain serotyping, attaches to the outer core.

During chronic infection, P. aeruginosa undergoes significant changes in its LPS structure60,61,62. These alterations can affect the bacterium’s surface properties, influencing its interactions with the host immune system and susceptibility to antimicrobial agents. Modified LPS can impact the effectiveness of R-pyocins and phages, leading to reduced susceptibility. Understanding these changes is crucial for developing effective treatments and managing chronic P. aeruginosa infections. LPS mutants of P. aeruginosa, particularly those that down-regulate or lose O-antigen genes, are commonly found not only in CF lung infections but also in other types of infections, including burn wounds and surgical wounds63,64,65. These mutants may be successfully treated with R-pyocins or LPS-binding phage depending on the moieties and the LPS residues made available by the mutations. Others have suggested the importance of LPS packing density on R-pyocin and tailocin susceptibility, though little is understood about the mechanism or regulation of this behavior53,54. More work is necessary to further understand these LPS-modifying behaviors and the resulting effects on the success of LPS-binding phage and bacteriocins in these infections.

Impact of P. aeruginosa heterogeneity on R-pyocin genotype and receptor availability

In chronic CF lung infections, populations of P. aeruginosa exhibit significant heterogeneity, which complicates treatment efforts. This heterogeneity arises from the genetic and phenotypic diversity within bacterial populations arising as the infection becomes chronic and selective pressures leading to subpopulations that exhibit varying levels of antibiotic tolerance, increased resistance, and heteroresistance66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75. These adaptive strategies allow different variants to survive, making it difficult to eradicate the infection with standard antibiotic therapies61,76. As a result, treatments often fail to completely clear the infection, leading to persistent and recurrent infections that pose significant challenges in clinical management.

Our study recently found a high frequency of R2-pyocin-susceptible strains in CF lung infections, despite these strains otherwise exhibiting heterogeneity across variants of the same strain77. Our work also found no correlation between LPS phenotype (presentation of O-antigen or common antigen) and R2-susceptibility in strains evolved in chronic infection, suggesting other LPS-modifying behaviors are also at work in the CF lung environment77. This data suggests that there is not a strong selective pressure for P. aeruginosa to alter LPS in a way that leads to R2-pyocin resistance in the CF lung and that R2 pyocins could be effective against P. aeruginosa for the majority of individuals with chronic lung infections.

In 2021, we also evaluated R-pyocin genotypes among P. aeruginosa isolates published through the International Pseudomonas Consortium Database (IPCD) and found that R1-pyocin producers make up the majority of typeable CF strains78. This suggests that many CF infections may initially be colonized with R1-producing ancestor strains or that there is a possible benefit to producing R1-type pyocins during strain competition in the early stages of infection. Our findings agree with previous work, as R1-producers have been shown to be the most prevalent subtype of CF isolates evaluated in a separate study which typed 24 P. aeruginosa CF isolates (62.5% of which were R1-producers)8. It is also interesting to note that a large number of strains from the IPCD could not be typed by the screen using classical R- pyocin typing methods, the majority of which (98%) were missing the entire R-pyocin structural gene cassette (PA0615-PA0628). Another group evaluating R-pyocin susceptibility among 34 CF isolates found that 23 (68%) of the tested isolates could not be typed or did not produce R-pyocins79. This suggests that CF isolates of P. aeruginosa initially possessing R-pyocin genes may lose the ability to produce R-pyocins later in chronic infection, however further study is necessary to explore the potential fitness advantages of this evolutionary trajectory. On the other hand, Bara et al. have shown greater numbers of CF isolates of P. aeruginosa contained genes for R-pyocin production when compared to environmental isolates80. It is of interest to note that many of the R1-producing strains tested across multiple studies were found to be susceptible to R2 pyocins, further corroborating the efficacy of R-pyocins and specifically R2 pyocins as effective antimicrobials against strains of P. aeruginosa isolated from infections8,81.

R-pyocins in “high-risk” P. aeruginosa strains and their prevalence in clinical isolates is a crucial area of research, particularly given the escalating concern about multidrug-resistant (MDR), and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) and pan-drug-resistant (PDR) P. aeruginosa strains82. Sequence type 235 (ST235) is one such high-risk clone that has gained global attention due to its widespread distribution and association with various antibiotic resistance mechanisms, including the production of metallo-β-lactamases. ST235 is frequently implicated in nosocomial outbreaks and is known for its enhanced ability to acquire and spread resistance determinants83. A recent study analyzing 32 clinical P. aeruginosa isolates found that R5-type pyocin genotype was the most prevalent, with 21 out of 32 strains (65.6%) possessing this subtype84. Interestingly, the authors observed a relationship between the R-pyocin subtype and both the sequence type (ST) and serotype of the isolates. For example, R5-type pyocins were associated with ST235 and serotype O11, as well as ST175 and serotype O4. This association between R5 pyocins and ST235 is particularly noteworthy given the clinical significance of this sequence type. However, these findings are in contrast with other studies that noted the R1-type pyocin genotype to be more prevalent in respiratory and cystic fibrosis (CF) isolates78. These conflicting data underscore the importance of investigating R-pyocin susceptibility of P. aeruginosa strains from various infection types. Moreover, these data could potentially inform the development of novel therapeutic approaches targeting these problematic strains, such as developing R-pyocin-based treatments tailored to specific infection types.

Self-sensitivity and immunity

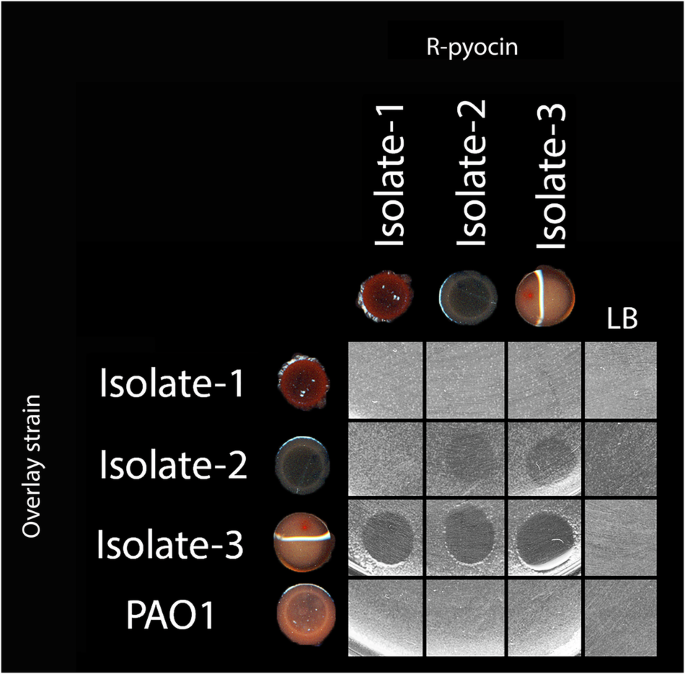

There are no known immunity proteins to protect producing strains from being targeted by R-pyocins of their kin; however, a number of studies have suggested the strains tested to be resistant to the R-pyocins they produced15,25,32. Despite the perpetuating dogma of a strain maintaining resistance to its own R-pyocin, we report that this is not always the case. We tested self-susceptibility using three P. aeruginosa variants isolated from chronic cystic fibrosis lung infection; while all three isolates are of the same strain (ST2999, as determined by multi-locus sequence typing (MLST)), each has distinctly different genomes and exhibited phenotypic heterogeneity78. We found that some strains can, in fact, be killed by the pyocins they produce (Fig. 6). When we spotted purified R-pyocins collected from each of these isolates onto lawns of the same strains, we found zones of inhibition for two of the three isolates. We hypothesize that this susceptibility is likely due to mutations in the receptor (LPS) or regulation of the receptor, allowing the R-pyocins to access, bind, and kill the producing strain. These isolates were previously characterized and typed as having the R1-pyocin genotype (bearing the R1-pyocin tail fiber sequence)78.

Isolates 1–3 were collected and characterized previously and determined to be R1-pyocin producers. R-pyocins from each of the three isolates were collected, then spotted against lawns the producing isolate, as well as the other two isolates of the same strain. Isolate 1 was resistant to its own R-pyocins, and those of its kin. Isolates 2 and 3 were susceptible to their own R-pyocins as well as the R-pyocins of each other. The R2-pyocin-producing lab strain PAO1 was included as a control. These data suggest that not all strains are resistant to the R-pyocins they produce. Adapted from Mei et al.78.

R-pyocin activity during infection

While a strain may carry R-pyocin genes in the genome, this does not guarantee R-pyocin transcription, nor its assembly of a complete, active R-pyocin particle. Little is known regarding the expression or activity of R-pyocins in vivo, and there have currently been no studies published with the intention to specifically evaluate R-pyocin transcriptomic or proteomic behavior during infection. As it is suspected that the infection environment is often stressful for pathogens, due to the activities of the innate immune response (oxidative stress), nutrient limitation, and metal sequestering, it is of interest to determine if infections do induce R-pyocin production. A survey of 15 published cystic fibrosis sputum transcriptomes found that 9 of these samples (60%) did not contain any detectable transcripts for R-pyocin structural genes (PA0615-PA0628), yet all exhibited low levels of transcripts for the R-pyocin lytic genes (PA0614, PA0629-PA032) and the adjacent regulatory genes (PA0612-PA0613)85,86. In a proteomic study analyzing a different set of 35 CF sputum samples from 11 individuals, the R-pyocin sheath protein (PA0622) was identified with a fold-change of >2-fold in three of these sputum samples87. This suggests that the in vivo cystic fibrosis lung environment can induce the transcription of R-pyocin genes; however, these do not seem to be highly induced, and interestingly, in cases where strains lack the R-pyocin structural genes, they appear to be able to maintain the expression of lytic and regulatory genes. When reviewing published transcriptomic data from in vitro sampling in Synthetic Cystic Fibrosis Sputum Media with the wild-type laboratory P. aeruginosa strains PA14 and PAO1, we find that all samples produced transcripts for the R-pyocin-associated regulatory genes, lytic genes, and structural genes (PA0612-PA0632)85,86,88. As most of these genes show upregulation in the artificial CF sputum environment it suggests that the nutritional environment mimicking that of the CF lung may induce or upregulate R-pyocin production in laboratory strains. More sampling and genomic data are necessary to better understand why some human sputum samples appear to lack transcription for R-pyocin structural genes.

Therapeutic development

Stability

R-pyocins exhibit impressive stability in various buffer conditions and storage environments, which is crucial for pharmaceutical formulations and long-term storage. Studies have shown that R-pyocins maintain their stability in TN50 buffer (50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5), a common buffer used in laboratory settings5,19,89. Notably, Scholl and Martin demonstrated that R2 pyocins retain more than 90% of their activity for at least 60 days when stored at 4 °C in TN50 buffer without the need for additional preservatives25,89. This long-term stability at low temperatures is a significant advantage for their potential therapeutic use, indicating that R-pyocins could be stored and transported with relative ease. Such stability characteristics are crucial for clinical applications, as they suggest that R-pyocin-based therapeutics could have a long shelf life and be distributed without the need for complex cold chain management.

Another notable characteristic of R-pyocins is their resistance to proteolytic enzymes. R-pyocins exhibit resistance to trypsin and other proteinases5,19. Protease resistance is a significant advantage for potential therapeutic use, as it suggests R-pyocins could maintain activity in protease-rich infection sites.

Safety

The in vivo efficacy of R-pyocins, including their stability, antimicrobial activity, and safety profile, have been investigated in several studies, providing crucial insights into their therapeutic potential8,23,24,81,89. Scholl and Martin’s mouse peritonitis model demonstrated the remarkable efficacy of R-pyocins against P. aeruginosa infections89. R-pyocin treatment resulted in a several-log reduction of bacterial load in blood and spleen samples, demonstrating their potent bactericidal effect in vivo89.

The safety profile of R-pyocins is also promising. While specific in vitro cytotoxicity data is limited, studies have shown that R-pyocins have low toxicity to mammalian cells in vivo24,89. Studies have demonstrated that R-pyocins do not significantly induce the production of pro-inflammatory or anti-inflammatory cytokines when injected intravenously in mice, with cytokine levels remaining similar to those of control mice89. This low cytotoxicity and minimal immune response induction suggest a favorable safety profile for potential therapeutic use. While R-pyocins showed high efficacy in initial treatments, it was observed that repeated exposure could lead to the development of neutralizing antibodies—although the immune response did not significantly diminish the efficacy of R-type pyocins upon retreatment89. This potential immunogenicity is an important consideration for the development of R-pyocin-based therapeutics, particularly for conditions that might require repeated or prolonged treatment, as has been described for phages as well90,91,92,93. Further investigation of the cytotoxicity and immunological responses are needed to fully characterize the safety and efficacy of R-pyocins.

Therapeutic delivery options

Recent advances in therapeutic delivery options for chronic bacterial infections have shown promise in improving treatment efficacy and patient outcomes. Intravenous (IV) administration remains a cornerstone for treating severe infections, particularly when high systemic concentrations of antibiotics are required. Advances in IV formulations have led to improved stability and bioavailability of drugs, enhancing their efficacy against persistent bacterial populations. Phage therapy has been pioneered as a developing alternative method of chronic infection treatment, particularly in treating drug-resistant P. aeruginosa infections, although its use is limited to clinical trials and last-resort cases thus far16,17,57,58,94. These case reports of phage treatment have utilized IV delivery to treat P. aeruginosa respiratory infections with no reported adverse effects16,17,57. When considering IV as an R-pyocin delivery option, it is important to note that R-pyocins are stable in buffered saline solution and maintain stability superior to phage during handling due to their lack of the fragile, DNA-containing capsid. As R-pyocins do not replicate like phage, the delivery of a high concentration is also important to achieve successful reduction in bacterial burden. R-pyocins could be administered either by treating with a single R-pyocin type or by using a cocktail with multiple subtypes of R-pyocins, similar to the use of multiple phages in phage cocktails58,95,96,97.

Another delivery could involve the use of PLGA (poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)) microparticles, which can encapsulate antibiotics or other antimicrobial agents, providing a controlled and sustained release directly to the site of infection98. This targeted delivery helps in maintaining therapeutic concentrations over extended periods, reducing the frequency of dosing and potential side effects. These microparticles have been shown to be an effective vehicle for administering phage, thus they have potential as a delivery method for R-pyocins and could be incorporated into existing inhalation regimens for individuals with chronic lung infections.

Hydrogels have also emerged as a valuable delivery system due to their ability to retain large amounts of water and release drugs in a controlled manner. They can be applied directly to wound sites, offering a moist environment that promotes healing while continuously delivering antimicrobials. Hydrogels have particularly gained momentum in phage delivery, and a number of different hydrogel compositions have been shown to be successful in phage delivery to wound sites97. Given the structural similarities between bacteriophage and R-pyocins, hydrogels are a plausible option for topical R-pyocin delivery to chronic wounds.

Inhalation therapy has maintained traction, especially for lung infections in cystic fibrosis patients, as inhaled antibiotics deliver high local concentrations directly to the lungs, minimizing systemic exposure and reducing side effects. This method is particularly beneficial for managing chronic respiratory infections caused by P. aeruginosa. Another potential method of delivering R-pyocins to treat lung infections could be purification followed by lyophilization, which could be used along with inhaled antibiotics.

Recombinant R-pyocins present another innovative approach to therapeutic intervention, leveraging engineered versions of the bacteriocins to selectively target and kill specific bacterial strains or species, particularly those involved in various infections23,24,25. When incorporated into a cream formulation, recombinant R-pyocins have demonstrated effective localized bacterial control on the skin, showing potential in managing burn-related infections and reducing biofilm formation24. This topical application ensures targeted delivery with minimal systemic side effects, enhancing the practical therapeutic potential of R-pyocins in treating persistent skin infections. It is important to note that in studies testing R-pyocins to treat infections in vivo, the R-pyocins have been purified from both P. aeruginosa or E. coli, either natively or recombinantly, respectively8,23,24,32,81,89. It is currently unknown if one purification method is superior to the other, and more studies are necessary to examine and compare the impact of these production methods of R-pyocins as considering them therapeutic agents.

R-pyocins have been found naturally capable of targeting clinically relevant bacterial species other than P. aeruginosa, including infectious strains of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Haemophilus ducreyi99,100,101. This is likely due to conserved residues of the LPS across these strains that present similar to the LPS of P. aeruginosa. While they can be effectively used to kill target species without modification, they have also been successfully engineered to broaden their spectrum of killing activity against other P. aeruginosa strains and even other pathogenic bacterial species like Escherichia coli, showing promise as an antimicrobial that can easily be engineered for effectiveness against a particular strain or species23,25. As phages have been utilized as alternative treatments against a number of chronic and multidrug-resistant infections, including those caused by Achromobacter, P. aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, R-pyocins and the R-type bacteriocins of many other species also have the potential to serve as alternative therapeutics17,57,58,102,103.

Concluding remarks

R-pyocins exhibit considerable potential as antimicrobial agents, offering unique benefits over conventional phage therapy due to their species-specific targeting, stability, and non-replicative nature. Advances in R-pyocin engineering and delivery methods, such as encapsulation and hydrogel applications, could demonstrate versatility for treating various infections. While current research indicates favorable in vivo efficacy and minimal immune response, future studies should focus on addressing potential immunogenicity and optimizing delivery methods for disparate clinical applications.

R-pyocins offer a controlled, stable, and specific antimicrobial approach that overcomes several challenges associated with phage therapy, including risks of gene transfer and instability. While phages require live bacteria to maintain replication and work as an antimicrobial, R-pyocins can more effectively be used in conjunction with bactericidal or bacteriostatic antibiotics because they do not require bacterial replication to kill target cells. Their non-replicative nature and adaptability make them a promising therapeutic for precision-targeting resistant infections, warranting consideration alongside phages. Given these advantages, R-pyocins represent an innovative addition to the antimicrobial arsenal. Their controlled activity, stability, and specificity make them suitable for precision medicine approaches, particularly for patients with complex infections. Although phage therapy has been pioneering this field, R-pyocins deserve similar, if not greater, investment in research and clinical trials. While it is unclear why R-pyocins have not yet deployed as alternative therapies alongside phages, perhaps more work is necessary in the areas of showing R-pyocin efficacy in vivo using recombinant or modified R-pyocins, R-pyocin subtype cocktails, and routine clinical methods of treatment (ie. IV and inhaled). While these areas did not necessarily hold phage therapy from progress, perhaps these conceptual studies could pave the way to push R-pyocins into clinical trials and accelerate the progress of using these reagents in the clinic. Developing safe and effective delivery methods and understanding immunogenicity in human models will further solidify R-pyocins as a viable, safer alternative to phage therapy in tackling resistant bacterial infections.

Responses