Racial and ethnic differences in prenatal exposure to environmental phenols and parabens in the ECHO Cohort

Introduction

Gestational exposure to environmental endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) is widespread [1, 2]. Environmental phenols (EPs), including parabens, are types of EDCs with reported estrogenic, anti-androgenic, and thyroid-hormone effects [3]. These chemicals are employed in the manufacture of polycarbonate plastics, food packaging, heat transfer papers like receipts, and medication, among other commercial products, and as ultraviolet filters and preservatives in sunscreens, personal care products, and processed foods as summarized in Supplementary Table 1 [4,5,6,7,8]. Exposure occurs through consumer items, food packaging, personal care products, and household dust [9, 10], and many EPs readily cross the placenta to expose the developing fetus [11]. Despite short in vivo half-lives, EPs are detected frequently in human biospecimens, underscoring their pervasive nature. Prenatal exposure to EPs has been associated with reproductive morbidities, infertility, adverse birth outcomes, altered fetal and child development, and long-term health risks among offspring, possibly partially accounting for poorer reproductive health outcomes among minoritized populations [12,13,14].

Results of U.S. biomonitoring studies, using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, indicate that EP exposure tends to be disproportionately experienced by non-White and low-income groups in the general population [15,16,17,18,19]. Previous studies of urinary EPs among pregnant people in the U.S. have also reported racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in exposure to EPs [20,21,22,23,24]. Residents of socioeconomically disadvantaged and minoritized communities may experience greater risks of exposure to EPs than advantaged and non-Hispanic White communities, due to greater proximity to industry and waste management facilities, and a limited selection of consumer products and fresh foods [25]. However, these previous studies were limited in size and scope, mostly offering insight into the nature and extent of the exposure disparity on a local basis and/or did not consistently report racial/ethnic differences with adjustment for social determinants. No studies have comprehensively characterized the differences in concentrations of EPs among pregnant people with various self-reported racial and ethnic identities and across different regions of the U.S. [26].

We leveraged extant urinary gestational EP data from 11 cohorts across the U.S. and Puerto Rico within the Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Cohort to help address this important public health data gap. Synthesizing results across multiple studies from different U.S. regions can help inform policy makers on target priorities to eliminate disparities in exposure to EDCs among pregnant populations at a large scale. We selected the EPs for study based on a high reported prevalence of exposure in U.S. study populations, evidence of endocrine disruption, and availability in the ECHO cohorts. We hypothesized that non-White pregnant people would have higher urinary concentrations of most EPs than their White counterparts, conditional on social determinants.

Methods

Study participants

The ECHO Cohort consists of mother–offspring pairs in 69 different birth cohorts from across the U.S. [27]. All participants completed written informed consent for participation in their cohorts and consented to data sharing with the ECHO program. We excluded cohorts with <30 eligible participants and participants were required to have at least one urine specimen collected during pregnancy, with laboratory determination of at least one EP, leaving 4139 participants from 11 ECHO cohorts (96.8% were singleton pregnancies, 3% were missing, and 0.2% were multiple gestations). We retained only singleton pregnancies. Thus, a total of 7854 urine specimens from 4006 participants from 11 ECHO cohorts were included in the final analytic sample (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2; Supplementary Table 2). The study protocol was approved by the single ECHO institutional review board, WIRB Copernicus Group Institutional Review Board.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Participants self-reported their racial/ethnic identities, which we subsequently categorized as Hispanic of any race, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and non-Hispanic Other—a category that included non-Hispanic Asian, Hawaiian, American Indian, Alaskan Native, multiple races, and other racial identities (the small number of participants in each group precluded statistical analysis of the individual identities). Race is a social construct, used in this analysis as a proxy for individual and systematic lived experiences of racism and discrimination resulting from complex prior and ongoing historical processes based (primarily) on racial grouping [28, 29]. Participants also self-reported their highest completed level of education, used as a proxy for socioeconomic position [30]. Educational level was categorized as ≥bachelor’s degree and <bachelor’s degree based on differences in social advancement and lifetime earnings potential [31]. Home address was geocoded in a subset of participants and categorized using Social Vulnerability Index (SVI), a census tract-level composite indicator variable of neighborhood stressors that incorporates 16 measures of socioeconomic status, household characteristics, racial and ethnic minority status, and housing type and transportation [32].

Urinary EP measurements

Participants provided one or more urine specimens during pregnancy, which were analyzed for EPs by participating laboratories (Supplementary Table 2). We imputed chemical values measured below the limit of detection (LOD) as the LOD/√2 (Supplementary Table 3) [33]. Urine samples submitted to the different study laboratories were returned with either specific gravity or creatinine values. Every study participant had either a urinary specific gravity or urinary creatinine value reported. Depending on which was reported, a correction was applied to correct for differences in urinary dilution, by multiplying the measurement by the ratio of the creatinine or specific gravity in a reference population to the participant’s observed creatinine or specific gravity, respectively, using the Boeniger method [34], as recently recommended for combining cohorts with different measures of urinary dilution [35]. We considered the following EPs measured widely among participating cohorts and implicated as EDCs: 2,4-dichlorophenol (2,4-DCP), 2,5-dichlorophenol (2,5-DCP), benzophenone 3 (BP-3), bisphenol A (BPA), bisphenol F (BPF), bisphenol S (BPS), methyl paraben (MePb), ethyl paraben (EtPb), propyl paraben (PrPb), and butyl paraben (BuPb). Common routes and sources of exposure are summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

Data analysis

To estimate associations of racial/ethnic categories and educational level with urinary chemical concentrations, we applied linear mixed regression models with a censored normal distribution, including a random intercept for participants. Urine specimens were analyzed at different laboratories, employing different methods and instruments that had distinct LODs, so LOD values vary across the cohorts as shown in Supplementary Table 3. We used a censored regression model to help address this challenge in pooling the laboratory results from the different cohorts. Such models can accommodate varying left-censored observations lower than the LOD by partitioning the likelihood function into components predicting values lesser and greater than the LOD. Specifically, the model first creates an indicator variable that flags whether a measured value is below or above the LOD. This indicator variable is included in the model to appropriately account for differences in LOD across cohorts and optimization is either based on an expectation maximization algorithm or Gauss-Hermite quadrature [36, 37].

In all of the multivariable models, we adjusted for maternal highest education level, ECHO cohort, gestational age at specimen collection (in weeks), season of specimen collection, maternal age at specimen collection (in years), and maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index (in kg/m2) as fixed effects. Covariates were selected based on hypothesized relationships of racial/ethnic identity with urinary chemical concentrations according to the literature using a directed acyclic graph [38, 39] (Supplementary Fig. 3). We did not adjust for year of urine collection as it was colinear to study cohort. To evaluate effect measure modification in the pattern of associations, we stratified the educational level predictor model by racial/ethnic identity. To address the potential impact of neighborhood-level confounding and to disentangle influences of structural socioeconomic disadvantage from self-reported race/ethnicity, we performed sensitivity analyses in which we adjusted for SVI in a subsample of 2117 participants with a geocoded home address. To evaluate the influence of gestational age at urine collection, we performed sensitivity analyses using only second trimester data, which accounted for the majority of urine specimens collected. We also performed a leave-one-cohort-out analysis to assess the influence of individual ECHO cohorts.

We used multiple imputation by chained equations to impute missing covariates and pooled estimates from the imputed data sets using Rubin’s rules. During sensitivity analyses, the list of covariates adjusted in each model varied based on data availability. Stratifying the dataset exclusively to a specific race/ethnicity or educational level resulted in scenarios where certain variables did not exhibit variability and were excluded from the analysis. Furthermore, because of the unbalanced nature of repeated measurements, stratifying the dataset during sensitivity analyses resulted in datasets with one observation per subject or all observations above the LOD for certain strata. We used general linear or linear mixed effects models, respectively, in these scenarios. Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided p < 0.05. We further adjusted the type-1 error rate using a conservative Bonferroni approach for the effective number of tests of each predictor, as 0.05/10 = 0.005 [40]. Statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software, v.4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants

Study participants self-reported Hispanic (41.4%), non-Hispanic Black (12.2%), non-Hispanic Other (9.0%), and non-Hispanic White (36.9%) race and ethnicity (Table 1). Approximately half (46.8%) had completed a bachelor’s degree. The mean gestational age at urine collection was 20.1 weeks, with an interquartile range of 14–26 weeks.

Distributions of urinary EP concentrations

Ten urinary chemicals were measured in participants (Supplementary Table 4). Nine of the 10 EPs were detected in a majority of participants, except for BPF (40.31% > LOD). MePb had the highest median urinary concentration (58.56 µg/L), and BuPb had the lowest (0.16 µg/L). There were moderate to strong positive correlations among Log-transformed urinary EtPb, BuPb, MePb, and PrPb (r = 0.34-0.79), and between log-transformed urinary 2,4-DCP and 2,5-DCP (r = 0.58) (Supplementary Fig. 4). The distribution of urinary chemicals varied by ECHO cohort (Supplementary Fig. 5).

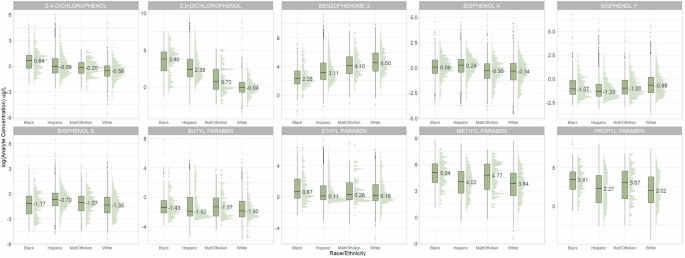

Boxplots of log-transformed urinary chemical concentrations are shown according to self-reported maternal racial/ethnic identity (Fig. 1). Non-Hispanic Black participants had higher urinary 2,4-DCP, 2,5-DCP, EtPb, MePb, and PrPb concentrations than participants with other racial/ethnic identities. Urinary BPA and BPS concentrations were highest among Hispanic participants, and BP-3 was highest among non-Hispanic White participants.

Urinary phenol concentrations (µg/L) corrected for urinary specific gravity or urinary creatinine. Abbreviations: ECHO Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes, Mult/Oth/Asian non-Hispanic multiple races, “Other,” and Asian.

Associations between self-reported maternal racial/ethnic identity category and urinary EPs

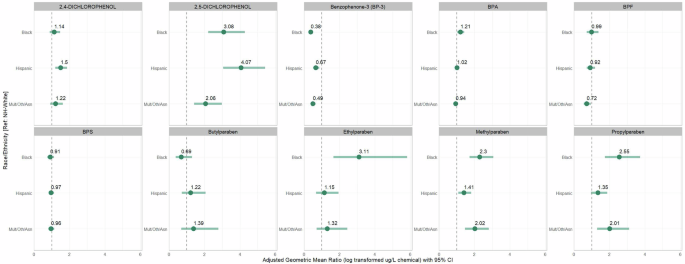

Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 5 show the covariate-adjusted associations between self-reported racial/ethnic identity and urinary chemicals. Relative to non-Hispanic White participants, Hispanic participants had 1.50-fold (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.20–1.87) and 4.07-fold (95% CI: 3.05–5.42) greater urinary 2,4-DCP and 2,5-DCP concentrations, respectively, but a 0.67-fold (95% CI: 0.52–0.85) lower urinary BP-3 level; non-Hispanic Black participants had 3.08-fold (95% CI: 2.22–4.27), 2.30-fold (95% CI: 1.73–3.06), 3.11-fold (95% CI: 1.66–5.82), and 2.55-fold (95% CI: 1.74–3.72) higher urinary 2,5-DCP, MePb, EtPb, and PrPb levels, respectively. Relative to non-Hispanic White participants, non-Hispanic Black participants had 0.38-fold (95% CI: 0.27–0.51) lower urinary BP-3 concentrations; non-Hispanic Other participants had 2.06-fold (95% CI: 1.42–2.99), 2.02-fold (95% CI: 1.46–2.80), and 2.01-fold (95% CI: 1.30–3.11) higher urinary 2,5-DCP, MePb, and PrPb levels, respectively, but a 0.49-fold (95% CI: 0.37–0.65) lower urinary BP-3 level.

Effect estimates are ratios of geometric means and 95% confidence intervals from individual linear mixed effect censored-response regression models of specific gravity/creatinine-corrected urinary phenol concentrations as outcomes and maternal racial and ethnic identity categories as predictors (non-Hispanic White = reference category), a random intercept on pregnancy to account for multiple urinary measurements and adjusted for maternal age (years), pre-pregnancy body mass index (kg/m2), educational level (completed vs. did not complete bachelor’s degree), gestational age at biospecimen collection (weeks), season of biospecimen collection (fall vs. winter vs. spring vs. summer), and ECHO study cohort (11 cohorts). Abbreviations: BPA bisphenol A, BPF bisphenol F, BPS bisphenol S, ECHO Environmental Influences on Child Health Outcomes, Mult/Oth/Asian non-Hispanic multiple races, “Other,” and Asian.

The results were similar, but somewhat attenuated, when we adjusted for the SVI in a sensitivity analysis of 2117 participants with a geocoded home address (Supplementary Table 6) and when we limited the analysis to urine specimens collected during the second trimester (Supplementary Table 7). The results of the leave-one-cohort-out analysis were mostly consistent with the main findings (Supplementary Fig. 6). However, exclusion of The Infant Development and Environment Study (TIDES) cohort changed the direction of the effect estimates, with urinary BPA concentrations similar between non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White participants and lower among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Other participants than non-Hispanic White participants. There were also increases in the magnitude of the association of race/ethnic identity with BPF among Hispanic participants and with BPS among Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic Other participants relative to non-Hispanic White participants when excluding the New York University Child Health and Environment Study (NYU-CHES) cohort.

Associations between maternal educational level and urinary EPs

Table 2 shows the associations between maternal educational level and urinary EPs, adjusted for covariates, according to maternal racial/ethnic identity. In all racial and ethnic groups, participants who had not completed a bachelor’s degree had lower urinary BP-3 than participants who had completed a bachelor’s degree or more, although with statistical significance only for Hispanic (0.68-fold; 95% CI: 0.55–0.84) and non-Hispanic Other (0.44-fold; 95% CI: 0.25–0.77) participants following the Bonferroni adjustment procedure. There was also a consistent pattern of higher urinary BPS and 2,5-DCP among participants who had not completed a bachelor’s degree in all racial and ethnic identity groups, although without statistical significance. Supplementary Table 8 shows a similar pattern of associations between maternal educational level and gestational urinary BP-3, BPS, and 2,5-DCP concentrations in the overall sample.

Discussion

In this investigation of 4006 pregnant ECHO participants, we found that average urinary EP concentrations differed by self-reported racial/ethnic identity. Non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic participants had greater average urinary concentrations of 2,5-DCP, the primary metabolite of paradichlorobenzene [4], than non-Hispanic White participants. Paradichlorobenzene is used in mothballs, fumigants, and room/toilet deodorizers, allowing the chemical to be inhaled [5]. It is neurotoxic and weakly antiestrogenic in rodents [41], and exposure has been associated with estrogen-sensitive cancers [42]. Urinary MePb, EtPb, and PrPb levels were also higher among non-Hispanic Black than non-Hispanic White participants. These chemicals are weakly estrogenic and used as preservatives in prepared foods and personal care products, allowing them to be ingested and absorbed [8]. Higher gestational exposure to MePb was associated with greater risks of adverse birth outcomes and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder among offspring [43]. In contrast, average urinary concentrations of BP-3, a UV-filtering chemical absorbed from sunscreens and personal care products, were highest among non-Hispanic White participants. BP-3 has been found to be estrogenic in experimental models, and exposure was associated with adverse reproductive outcomes in human studies [6]. However, we found that the associations did not differ by educational attainment, suggesting that factors other than educational attainment, as a proxy for socioeconomic position, played an important role in racial/ethnic differences. Differential exposure may account in part for racial/ethnic differences in perinatal health outcomes.

Comparison with previous studies

Pregnant people from across the U.S. with racial and ethnic identities other than non-Hispanic White had higher urinary concentrations of most measured EPs than their non-Hispanic White counterparts. Our results are largely consistent with the results of several previous studies of pregnant people that have also reported racial and ethnic differences in urinary EPs among smaller samples of the U.S. population from limited areas [20,21,22,23,24]. Biomonitoring studies have also described similar racial and ethnic differences in urinary EPs among representative samples of the general U.S. population [19, 44,45,46]. However, unlike the general U.S. population samples that included people without pregnancy, children, and seniors, our study focused on pregnant people.

Similar to our results, the 2009–2010 U.S. National Children’s Study Vanguard Study (NCS) of 506 pregnant women (some of whom were included in this analysis) showed higher urinary 2,5-DCP levels among non-Hispanic Black than non-Hispanic White participants [20]. Urinary 2,5-DCP levels were similarly lowest among non-Hispanic White participants and those with the highest educational level in the 2009–2014 Healthy Start study of 446 pregnant women from Colorado (some of whom were included in this analysis) [21]. African Americans, a non-Hispanic Black group, had the highest urinary 2,4-DCP and 2,5-DCP levels in the 2006–2008 LIFECODES study of 480 pregnant women from Boston, Massachusetts [22]. These results are consistent with our own findings and with those from a representative sample of U.S. women from 1999–2014, for whom urinary concentrations of 2,4-DCP and 2,5-DCP levels were higher among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic women than non-Hispanic White women [44]. Similar to the U.S. biomonitoring study, we did not find an association between urinary 2,4-DCP and 2,5-DCP and educational level [44].

In addition, our findings were consistent with results from a 2003–2004 study showing that U.S. non-Hispanic White participants had greater average urinary BP-3 than non-Hispanic Black and Mexican American participants [19]. Pregnant non-Hispanic White women had similarly higher urinary BP-3 concentrations than other racial/ethnic groups in the NCS and Healthy Start studies [20, 21], and BP-3 levels were positively correlated to educational level in the Healthy Start and LIFECODES studies [21, 22]. We also found higher BP-3 levels among pregnant people with more education.

BPA is a plastic monomer used in polycarbonate plastics, epoxy can linings, heat transfer papers, and other consumer goods [7]. BPA levels were similar across different racial/ethnic categories among U.S. women in 1999–2014 [44]. In contrast, urinary levels of BPS, a BPA-replacement chemical, were highest among non-Hispanic Black women, and urinary levels of BPF, another BPA replacement, were highest among non-Hispanic White women from 1999–2016; these differences could not be attributed to income as an indicator of socioeconomic position [44]. Urinary BPS and BPA were similarly highest among non-Hispanic Black U.S. adults from 2007–2016, but there was no significant difference in BPF; concentrations were greatest among those with the lowest education [45]. In contrast, urinary BPA levels were similar among 233 non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, and Other (including Asian, Black, and multiracial) pregnant California women enrolled in the Markers of Autism Risk in Babies–Learning Early Signs (MARBLES) study from 2007–2014, although those with less education had higher urinary BPA levels [23]. We did not find a statistically significant difference in urinary BPA, BPS, or BPF levels between racial/ethnic categories after the Bonferroni adjustment, although our results suggested higher urinary BPA among non-Hispanic Black compared to non-Hispanic White participants. We also did not find associations of BPA, BPF, or BPS with educational level. The differences between our results and those from U.S. biomonitoring data may in part reflect higher intraindividual variabilities in prior studies based on a single urine specimen [47] and different time-activity exposure patterns between pregnant and non-pregnant populations [48].

Our results were similar to those reported in a previous analysis of the Healthy Start Study, in which non-Hispanic Black participants and participants with other racial/ethnic identities had the highest urinary MePb, EtPb, and PrPb levels and non-Hispanic Black participants had the lowest urinary BuPb levels [21]. Higher education was related to higher urinary EtPb and PrPb levels in Healthy Start. Similarly, urinary MePb and PrPb levels were greatest among African American participants, whereas BuPb levels were greatest among White participants in the LIFECODES study [22]. In the Vitamin D Antenatal Asthma Reduction Trial (VDAART), a study of 467 pregnant women from Boston, Massachusetts, maternal plasma MePb and PrPb levels were lowest among non-Hispanic White participants, similar to our findings [24]. Likewise, urinary MePb, EtPb, and PrPb were higher among Hispanic participants and those with other racial/ethnic identities than among White participants in the MARBLES study, and PrPb levels were greater among those with less education [23]. In parallel to our findings among pregnant people, urinary MePb and PrPb concentrations were higher among U.S. non-Hispanic Black, Mexican American, and Other Hispanic participants than among non-Hispanic White participants in 1999–2014, and the differences could not be attributed to socioeconomic position [44].

The results of the current study in a large sample of pregnant people underscore the widespread nature of racial and ethnic differences in urinary EP concentrations, despite decreases in exposure to most EPs in all racial/ethnic groups over time [46].

Drivers of racial and ethnic differences in urinary EP concentrations

We found differences in urinary EP concentrations between racial/ethnic groups, primarily reflecting higher urinary concentrations among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic people than among non-Hispanic White people. Yet, we also found that most urinary EPs were similar for participants with different educational levels. These results suggest that the racial/ethnic differences in urinary EPs were similar among participants with different educational levels, which act as a surrogate for socioeconomic position. Personal care products intended for application to the skin, hair, and nails, as well as deodorizers, fragrances, perfumes, and cleansers, are an important source of exposure to parabens and benzophenones [9, 10, 49, 50]. Use of some personal care products differs among White and non-White women [51,52,53,54]. While preference and product availability are important, the imposition of Eurocentric beauty standards appears to be a key driver of exposure disparities in non-White populations [9, 51, 55, 56]. Use of products marketed to non-White populations to promote White beauty standards, such as hair relaxers and related haircare products, skin lighteners, and douche/vaginal wash products, can lead to higher EP exposures [12, 57]. Greater use of ethno-targeted beauty products has been associated with increased reproductive health risks [58,59,60]. Similarly, differences in consumption of processed, packaged, and canned foods leads to different EP exposures [45, 61, 62], and different patterns of product consumption during pregnancy may contribute to the exposure difference [63]. Unfortunately, product selection may be constrained by availability and cost [64], in addition to preference, so the success of individual actions to reduce exposure is likely to be limited; policy-level initiatives are necessary to intervene effectively on the exposure disparity [65]. Resolving the racial and ethnic difference in prenatal EP exposure will require intensive study of the exposure sources to inform greater regulatory attention, and investigation of racial and ethnic differences in perinatal outcomes and child health that can be attributed in part to the different levels of exposure.

Strengths and limitations

Our sample size of 4006 pregnant people with 7854 urine specimens provided statistical power to detect important differences in urinary EPs among pregnant people with different self-reported racial/ethnic identities. The results of our sensitivity analyses suggested that neighborhood-level confounding was unlikely to bias the results. However, the limited number of participants who identified as non-Hispanic Asian, Hawaiian, American Indian, Alaskan Native, multiple races, and as other racial and ethnic identities precluded analyses as separate groups. A future investigation with oversampling of pregnant people having these racial and ethnic identities is necessary to characterize EP exposure disparities. There were modest differences in effect estimates for urinary BPA, BPF, and BPS when we excluded the TIDES and NYU CHES studies, but most results were also robust to a leave-one-cohort-out analysis.

We measured multiple urinary EPs, including the newer BPA-analog compounds BPF and BPS. However, urinary EPs have short half-lives in vivo. Intraclass correlations ranged from 0.25 for BPS to 0.95 for EtPb in repeated urinary specimens collected at 2 week intervals in Healthy Start [21], suggesting that individual measures may not represent exposure across gestation for some chemicals. Still, we included multiple urinary measurements in the regression models for many participants. The results were also mostly similar in a sensitivity analysis limited to second-trimester urinary specimens, which may in part reflect higher concentrations of some EPs at delivery (24 samples collected at delivery) [66]. Furthermore, there were a large number of samples with BPF values lower than the LOD. We implemented a censored linear mixed effects model to accommodate the uncertainty due to these values. We also included cohort as a fixed effect in regression models to adjust for differences between ECHO cohorts, including using different laboratories to measure EPs [67].

Conclusions

Our results underscore the disproportionately high levels of exposure to EPs among pregnant racial and ethnic minorities in the U.S. Thus, studies of racial/ethnic differences in perinatal health outcomes should account for differences in chemical exposure.

Responses