Rapid and highly efficient recombination of crosslinking points in hydrogels generated via the template polymerization of dynamic covalent three-dimensional nanoparticle crosslinkers

Introduction

Smart hydrogels, such as self-healing and thermoplastic hydrogels, have been widely developed using dynamic covalent bonds (DCBs) as crosslinking points. DCBs exhibit reversible bonding and dissociation in response to external stimuli, endowing the hydrogels with self-healing properties and thermoplastic behavior [1,2,3,4]. When the DCBs dissociate, the functional groups on the hydrogel surface temporarily lose contact. However, under appropriate conditions, these groups reconnect, allowing the hydrogel to recover its structure and properties [5, 6]. Additionally, the dissociation of DCBs can significantly impact the structural stability of the hydrogel, imparting the hydrogel with thermoplastic properties [7,8,9].

When hydrogels crack or fracture, temporary dissociation of the DCBs occurs. Over time, the broken surfaces of the hydrogel can reattach, restoring the mechanical integrity of the hydrogel. The efficiency of this reattachment depends heavily on the diffusion of molecules within the gel. Molecular diffusion plays a crucial role in allowing the functional groups to come into contact and form new crosslinking points. However, steric hindrance—particularly from large polymer chains—can slow this diffusion, resulting in incomplete self-healing or delayed recovery of the gel’s properties [10, 11]. Recovery of the crosslinked structure occurs when the functional groups on the polymer come into contact, and the diffusion of molecules is the key factor determining readhesion performance [12, 13]. As the recombination of functional groups is time and temperature dependent, functional groups recombine when their density becomes high. Therefore, diffusion and mobility are crucial polymer characteristics for improving gel-to-gel reconnection [14, 15].

DCB-based hydrogels are typically prepared by mixing and connecting polymers through chemical or physical interactions. After mixing, the DCB-derived functional groups form DCBs to crosslink the polymers [1]. While some hydrogels demonstrate rapid self-healing properties, not all can completely recover due to the low diffusivity of polymers with high molecular weights and steric effects, which limit the reformation of DCB-based crosslinking points. This often results in nonuniform structures, which can reduce the ability of the hydrogel to fully recover its original physical properties after damage [1, 12, 15,16,17]. Consequently, some DCB-derived functional groups remain free in the gel, and the recombination reaction rate is low [5, 18, 19].

When many functional groups exist on the hydrogel surface, the formation of new crosslinking points on the surface results in fast adhesion between gels; however, not all functional groups reconnect, which prevents complete recovery of the physical properties of the hydrogel. Therefore, to promote the recombination of crosslinking points and fully recover the properties of the hydrogel, the effects of diffusion, mobility, and exclusion volume of the polymer must be reduced [18, 20, 21].

In this study, we address these limitations by employing phenylboronic acid-coated nanoparticles (PBA-NPs) as crosslinkers via a template polymerization technique. This approach allows for the preformation of DCBs between nanoparticles and smaller molecules, thereby increasing the density and uniformity of the crosslinking points within the hydrogel. By controlling the mobility of the polymer chains and improving the efficiency of DCB formation, we aim to overcome the challenges of molecular diffusion and steric hindrance present with traditional hydrogels.

The objective of this study was to develop a thermally responsive hydrogel with high crosslinking density through template polymerization. We hypothesize that by controlling the diffusion and arrangement of the polymer chains around the nanoparticle crosslinkers, we can produce a hydrogel that exhibits rapid self-healing, high thermal hysteresis, and robust mechanical properties. Furthermore, we explore the fundamental principles of DCB-based crosslinking and provide a framework for designing next-generation smart hydrogels with improved functionality.

Results and discussion

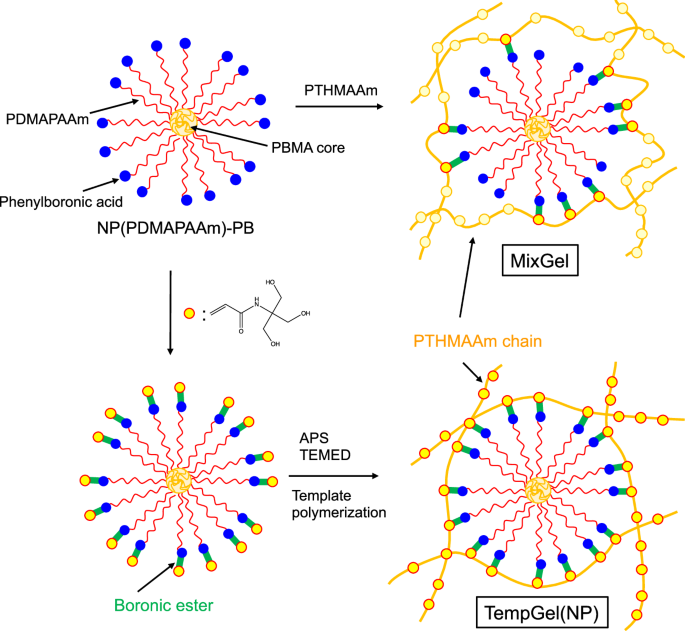

Phenylboronic acid-functionalized nanoparticles (PBA-NPs; volume average diameter: 54 ± 0.16 nm) were prepared by the assembly of ω-PBA-poly(butyl methacrylate)14–b-poly(N,N-dimethylaminopropyl acrylamide)74 (PBMA-b-PDMAPAAm-PBA), as previously reported [1]. In the first step, the PBA-NPs and N-[Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl] acrylamide (THMAAm) were mixed in water to form boronic ester bonds between the PBA on the NP surface and the hydroxyl groups on THMAAm. The THMAAm was subsequently polymerized using ammonium persulfate (APS) and N,N,N’,N’-tetramethyl ethylenediamine (TEMED) to obtain a hydrogel, which was denoted TempGel(NP) (Fig. 1). Similarly, a hydrogel was prepared via the conventional method of mixing PBA-NPs and PTHMAAm and is referred to as MixGel(NP) (Fig. 1). The changes in the thermal viscoelasticity of the two hydrogels, TempGel(NP) and MixGel(NP), were then investigated using a rheometer.

Schematic of hydrogel preparation by mixing the PTHMAAm chain and PBA-NPs (MixGel(NP)) and template polymerization of THMAAm using PBA-NPs as crosslinkers (TempGel(NP))

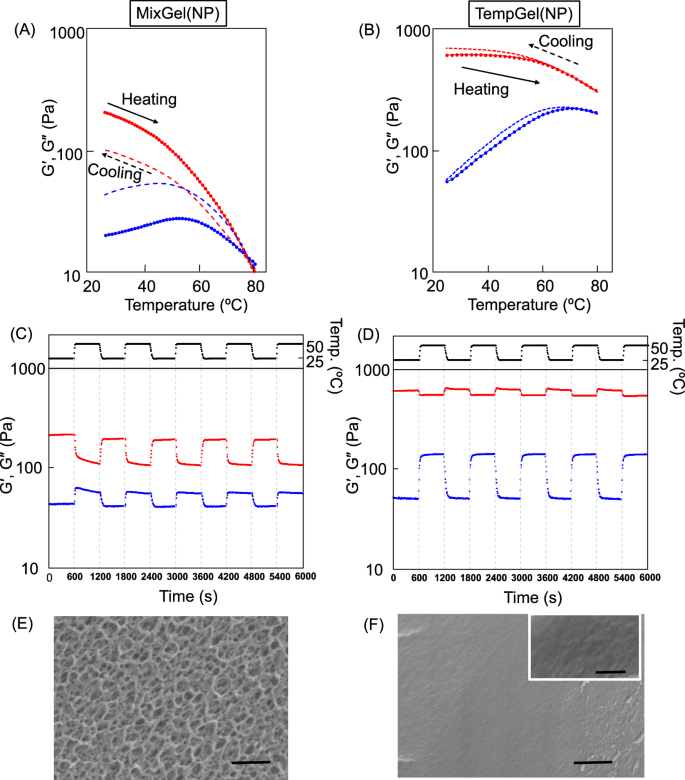

In the case of MixGel(NP), the storage modulus (G’) gradually decreased as the temperature increased above 25 °C. Additionally, the loss modulus (G’’) of the hydrogel slightly increased until a temperature of 60 °C was reached, after which it decreased (Fig. 2A). As the temperature decreased from 80 °C, the G’ and G’’ values of the hydrogel recovered with decreasing temperature, indicating hysteresis behavior. However, the final values of G’ and G’’ were not the same as those of the original hydrogel at 25 °C. In fact, the G’ value of the MixGel(NP) after four thermal cycles was 90% that of the value of the original hydrogel (Fig. S3). This suggests that while the hydrogel exhibited reversible thermal behavior, the crosslinked structure did not entirely return to its initial state after thermal cycling, leading to a slight decrease in the elastic modulus compared with that of the original hydrogel.

Changes in the thermal viscoelasticity of (A) MixGel(NP) and (B) TempGel(NP). The red and blue lines represent the changes in G’ and G’’, respectively, with respect to temperature. The solid and dashed lines indicate the heating and cooling processes (5 °C/min), respectively. Changes in G’ and G’’ of (C) MixGel(NP) and (D) TempGel(NP) at 25 and 50 °C over time. The temperature alternated between 25 and 50 °C every 10 min. The red and blue dots indicate G’ and G’’, respectively. SEM images of (E) MixGel(NP) and (F) TempGel(NP). Scale bar: 1 μm. The scale bar in the inset in (F) is 200 nm

In contrast to that of MixGel(NP), the elastic modulus (G’) of TempGel(NP) remained relatively constant as the temperature increased to 60 °C and then gradually decreased at temperatures above 60 °C. Interestingly, the loss modulus (G’’) of TempGel(NP) increased as the temperature increased to 60 °C (Fig. 2B). High hysteresis was observed when cooling TempGel(NP). To further investigate the thermoresponsive behaviors of the hydrogels, changes in their viscoelasticity were observed over time during temperature cycling between 25 °C and 50 °C (Fig. 2C, D). TempGel(NP) exhibited a significant change in thermal viscoelasticity, whereas MixGel(NP) did not recover its original elastic modulus (G’) value after being held at a lower temperature for 10 min following high-temperature treatment. In our previous work, a hydrogel prepared by mixing PBA-NPs and poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA) instead of PTHMAAm exhibited similar behavior, where the crosslinking points were not reorganized as the temperature decreased after they had dissociated at high temperatures [1]. Our current results suggest that the hydrogel preparation method has a significant effect on the thermal viscoelastic properties and that compared with conventionally prepared MixGel(NP), TempGel(NP) has high hysteresis and structural stability.

As mentioned earlier, MixGel(NP) was prepared via a conventional method, which involved mixing two macromolecules, PBA-NPs and the PTHMAAm polymer, to form boronic ester crosslinks. For boronic ester formation to occur, the PBA groups on the surface of the NPs need to interact with the diol groups on the PTHMAAm molecules. However, the low diffusion, limited mobility and steric hindrance of the large PTHMAAm molecules reduce the efficiency of boronic ester formation. Such inefficient crosslinking results in MixGel(NP) having relatively low viscoelasticity compared with hydrogels prepared by other methods. The physical limitations of the mixing approach, such as the significant diffusion and interactions between the large polymer chains and nanoparticles, lead to the crosslinking density and mechanical properties of the resulting MixGel(NP) being suboptimal.In our previous study, the thermoresponsive behavior of the boronic ester formed between PBA-NPs and PVA was investigated. The boronic ester bond dissociated at temperatures between 25 and 30 °C and had almost completely dissociated at temperatures above 60 °C (with a half-dissociation temperature of 46 °C) [1]. Therefore, in the case of MixGel(NP), the boronic ester crosslinks gradually collapsed as the temperature increased. Additionally, the increased mobility of the PTHMAAm polymer chains, which form the backbone of the hydrogel, caused the hydroxyl groups on PTHMAAm to shift away from the PBA groups on the NP surface. As a result, at temperatures above 60 °C, when all the boronic ester bonds had dissociated, the NP and PTHMAAm chains existed independently as a solution. For the boronic ester bonds to reform upon cooling, the PBA groups on the NPs and the hydroxyl groups on the diffused PTHMAAm chains need to reassociate. However, this recombination process was suppressed and incomplete because of the excluded volume effect of the large PTHMAAm molecules. Furthermore, not all the PBA groups on the NPs were able to form boronic ester bonds with PTHMAAm chains. This led to an overall low crosslinking density and suboptimal viscoelastic properties in the final MixGel(NP).

THMAAm is a small monomer with three hydroxyl groups that are readily available for interaction with the phenylboronic acid (PBA) groups on the nanoparticle surface. The small size and molecular structure of THMAAm allow greater accessibility to PBA units, facilitating the formation of stable boronic ester bonds. In contrast, PTHMAAm is a high-molecular-weight polymer. Owing to its large size and steric hindrance, the polymer chains can have reduced mobility and limited access to the boronic acid groups on the nanoparticles. This limits the formation of boronic ester bonds in MixGel(NP), as fewer hydroxyl groups are available for interaction with the PBA units [22].

The template polymerization method used to form TempGel(NP) ensures that each PBA nanoparticle is surrounded by multiple THMAAm monomers, creating a multivalent network of boronic ester bonds. This high-density crosslinking contributes to the improved thermal stability and rapid self-healing properties observed in TempGel(NP). In MixGel(NP), the large PTHMAAm polymer chains are more sparsely arranged, and fewer boronic ester bonds form. This leads to a less dense crosslinked network, which may explain the lower thermal stability and less effective recovery of MixGel(NP) after thermal cycling [23].

TempGel(NP) was prepared via a template polymerization method from PBA-NPs and the low-molecular-weight THMAAm monomer. In this approach, all the PBA groups on the NP surface were able to form boronic ester crosslinks with the THMAAm monomers during polymerization. After polymerization, the resulting PTHMAAm polymer chains densely surrounded the NPs, forming a multivalent boronic ester network. As the temperature increased, the number of boronic ester crosslinks gradually decreased. However, even as the crosslinking density decreased, the PTHMAAm chains did not diffuse away from the NPs because some of the boronic ester linkages remained partially intact. As shown in Fig. 2B, the loss modulus (G’’) of TempGel(NP) increased with temperature, whereas the elastic modulus (G’) remained relatively constant. This finding indicates that the TempGel(NP) system can modulate the fluidity parameter (G’’) without significantly changing its elastic (G’) properties. This is because the number of crosslinking points, determined by the NP content, remained largely unchanged up to 60 °C, at which temperature the boronic esters had fully dissociated. Above 60 °C, as nearly all the boronic esters had dissociated, G’’ remained constant, whereas G’ gradually decreased. This suggests that the mobility of the NPs within the hydrogel had reached saturation. In contrast, the MixGel(NP) prepared by the conventional mixing method allowed the PTHMAAm chains to diffuse away from the NPs because of the loss of boronic ester crosslinks.

Thermal hysteresis refers to the difference between the elastic and viscous responses of a hydrogel during heating and cooling cycles and can indicate the reversible nature of the crosslinking points and the structural stability of the hydrogel [24]. Interestingly, TempGel(NP) exhibited considerably high hysteresis during temperature cycling between 25 and 50 °C. This indicates reversible, thermally induced dissociation and reformation of the crosslinks. At 60 °C, TempGel(NP) had lost all of the boronic ester crosslinks between the NPs and the PTHMAAm polymer chains. However, at 50 °C, as discussed in the previous differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis, approximately 50% of the boronic ester crosslinks remained intact, resulting in the NPs and PTHMAAm still being connected [1]. This means that when the temperature was reduced from 60 °C, the dissociated boronic ester crosslinks were able to quickly reform. This rapid and efficient recombination behavior is analogous to the “zipper mechanism” observed in reactions between macromolecules. The numerous hydroxyl groups on the PTHMAAm chains closely surrounded the PBA groups on the NP surface, facilitating the quick reformation of the boronic ester crosslinks, and this reversible dissociation and recombination of the boronic ester crosslinks during temperature cycling is responsible for the observed high hysteresis in TempGel(NP).

To investigate the mechanism underlying the high hysteresis observed in TempGel(NP), the influences of hydrogel density, molecule diffusion and multivalency were analyzed. First, the density of the hydrogel was confirmed via scanning electron microscopy (SEM). As shown in Fig. 2 E, F, the conventionally prepared MixGel(NP) had a dense porous structure, similar to that of conventional hydrogels prepared via polymer reactions [25]. In contrast, TempGel(NP) exhibited a packed structure, where the NPs were densely and completely covered by the PTHMAAm polymer chains. These results indicate that the PTHMAAm chains had numerous hydroxyl groups on NP surface, which allowed the PBA groups to be in close proximity, facilitating the rapid reformation of the boronic ester crosslinks when the temperature decreased. The viscoelastic properties of TempGel(NP) quickly recovered even after heating to 80 °C, which led to complete dissociation of the boronic ester crosslinks. Furthermore, despite the dissociation of the boronic ester bonds, the NPs and PTHMAAm chains were still completely isolated. However, the dense packing structure of TempGel(NP) enabled rapid reformation of the boronic ester crosslinks, allowing the complete recovery of the viscoelastic properties of the hydrogel after short-term temperature treatment. This dense packing and close proximity of the hydroxyl groups and PBA moieties in TempGel(NP) is the key factor that enables the rapid and efficient reformation of the boronic ester crosslinks, leading to the observed high hysteresis behavior.

The small size and flexibility of THMAAm allow for the reversible formation and dissociation of boronic ester bonds as the temperature changes, leading to high thermal hysteresis. The bonds break at higher temperatures but rapidly reform as the temperature decreases, which contributes to the enhanced thermal stability and viscoelasticity of TempGel(NP). In contrast, the large PTHMAAm chains in MixGel(NP) exhibit slower recombination of the boronic ester bonds after heating. This slower recovery is attributed to the excluded volume effect, where large polymer chains are unable to reposition themselves efficiently within the gel matrix, resulting in less effective reformation of the crosslinked structure [23].

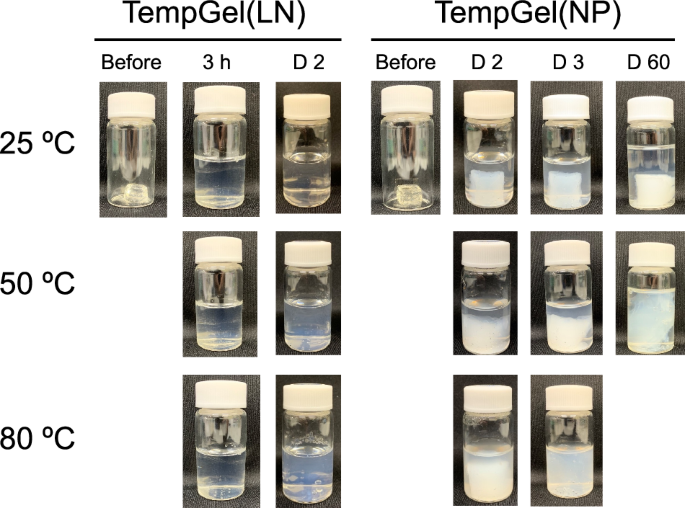

The internal mobility of TempGel(NP) was investigated. TempGel(NP) uses NPs to crosslink the PTHMAAm polymer, and the diffusion of the NPs is much slower than that of small molecules. For comparison, we also prepared TempGel using a linear polymer, P(APBA-co-DMAAm) (APBA/DMAAm = 475/25 (units)) (Fig. S4), which was denoted TempGel(LN). Then, TempGel(NP) and TempGel(LN) were incubated in a water bath at 25 °C, 50 °C and 80 °C (Fig. 3). For TempGel(LN), the hydrogel completely dissociated after just one day of incubation, regardless of the temperature. In contrast, TempGel(NP) maintained its structure for more than 60 days when the temperature was maintained at 25 °C. At 50 °C, TempGel(NP) partially maintained its structure throughout the duration of the experiment, but gradually swelled and slowly disintegrated over time. When exposed to 80 °C, the swelling of TempGel(NP) was faster than that at 50 °C, and TempGel(NP) had completely decomposed after just 3 days. These results indicate that TempGel(NP), with its NP crosslinks, has significantly lower internal mobility and diffusion than the linear polymer TempGel(LN), and this lower mobility contributes to the improved structural stability and slower disintegration of TempGel(NP) under various temperature conditions.

Photographs of TempGel(LN) and TempGel(NP) in water at 25, 50 and 80 °C

TempGel(LN) was crosslinked using the linear polymer P(APBA-co-DMAAm) and PTHMAAm. Since linear polymers can gradually diffuse out of the hydrogel, the hydrogel structure could not be adequately maintained. This is because the boronic ester crosslinks are generally in equilibrium, and a portion of them are dissociated even at 25 °C. Once the boronic ester crosslinks dissociate, the distance between PBA and the hydroxyl groups become significantly larger, making reconnection difficult. Additionally, the mobility of the linear polymers inside the hydrogel increased (Fig. 3), further facilitating their diffusion out of the hydrogel. In contrast, TempGel(NP) was crosslinked using NPs, forming a three-dimensional crosslinked structure. The diffusion of the NP crosslinkers was much slower than that of the linear polymers. At 50 °C, half of the boronic ester crosslinks had dissociated, whereas the other half remained intact to maintain the crosslinked structure. As a result, hardly any of the NPs diffused out of the hydrogel at lower temperatures. However, at higher temperatures, the boronic ester crosslinks gradually reformed due to the lower dissociation constant, leading to gradual disassembly of the hydrogel over time. The three-dimensional crosslinked structure and the slower diffusion of the NP crosslinkers in TempGel(NP) contributed to its improved structural stability and gradual disintegration compared with those of the linear polymer-based TempGel(LN).

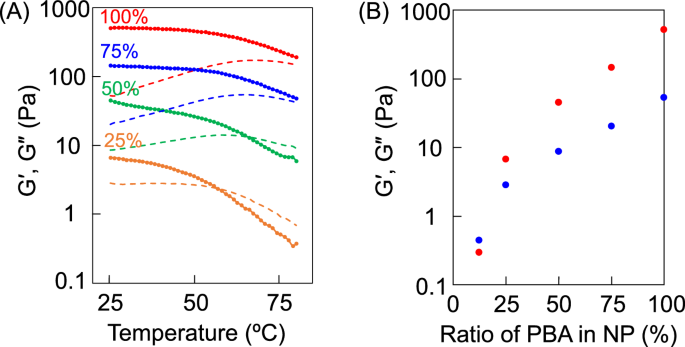

The stability of TempGel(NP) was examined by analyzing the formation of multivalent boronic ester bonds between the NPs and PTHMAAm (Fig. 4). Owing to the presence of multiple PBA units on the surface of the PBA-NPs, these units interact with the PTHMAAm chains in a multivalent fashion. To regulate the number of PBA units on the surface of PBA-NPs, poly(n-butyl methacrylate)-b-poly(N,N-dimethylaminopropyl acrylamide)-PBA (PBMA-b-PDMAPAAm-PBA) and PBMA-b-PDMAPAAm-DMAPAAm, which lack a PBA unit at their ω-terminus (Fig. S5), were utilized to assemble NPs.

A Changes in the thermal viscoelasticity of TempGel(NP) containing 100% (red), 75% (blue), 50% (green), and 25% (yellow) PBA on the surface of the PBA-NPs. The solid and dotted lines indicate G’ and G’’, respectively. B G’ (red dots) and G’’ (blue dots) of TempGel(NP) with different PBA densities on the surface of the PBA-NPs at 25 °C

As shown in Fig. 4, both the G’ and G’’ values of TempGel(NP) decreased as the amount of PBA on the PBA-NPs decreased. Specifically, a gel–sol phase transition was observed when the PBA content on the NP surface was less than 50%. In this study, the amount of PBA on the NP surface decreased, which kept the number of NP crosslinkers in the hydrogel constant regardless of the amount of PBA on the PBA-NPs. As shown in Fig. 2, while the G’ of the hydrogel remained stable, G’’ increased with increasing temperature. Consequently, when roughly half of the boronic ester bonds dissociated, the G’ of TempGel(NP) remained the same. However, reducing the amount of PBA on the PBA-NPs caused a decrease in both the G’ and G’’ values of TempGel(NP), indicating that the surface density of boronic acid on the NPs significantly influenced the viscoelasticity of the hydrogel. Given the equilibrium state of boronic esters, the high boronic acid density on the NP surface allowed the diols on PTHMAAm to rebind to nearby PBA units. In contrast, as the PBA density on the NP surface decreased, boronic ester formation was hindered due to the reduced concentration of PBA on the NP surface. Consequently, the viscoelasticity of the gel decreased because the crosslinks became less stable due to the lower local boronic acid density. These findings suggest that multivalency is influenced not only by the number of boronic acid ester bonds on the particle surface but also by the density of functional groups on the NP surface.

The PBA density on the nanoparticle surface plays a crucial role in determining the number of crosslinks that form between the nanoparticles and polymer chains (e.g., THMAAm). A higher PBA density leads to an increased number of boronic ester bonds, creating a more densely crosslinked network. This results in enhanced mechanical strength and a higher storage modulus (G’) since the network can better resist deformation under stress. Conversely, reducing the PBA density decreases the number of available crosslinking points, leading to a weaker gel with lower mechanical stability. The decrease in crosslinking density affects both the storage modulus (G’) and loss modulus (G’’), as the material is less able to retain its structural integrity under mechanical or thermal cycling. As the PBA density decreases, the ability of the hydrogel to maintain its structure after thermal or mechanical deformation is compromised. The reversible dissociation and reformation of boronic ester bonds are influenced by the local availability of hydroxyl groups to interact with PBA units. A high PBA density enables faster reformation of these bonds upon cooling or stress removal, leading to greater hysteresis and improved self-healing properties. At lower PBA densities, efficient network reformation is difficult, resulting in a slower recovery and reduced hysteresis.

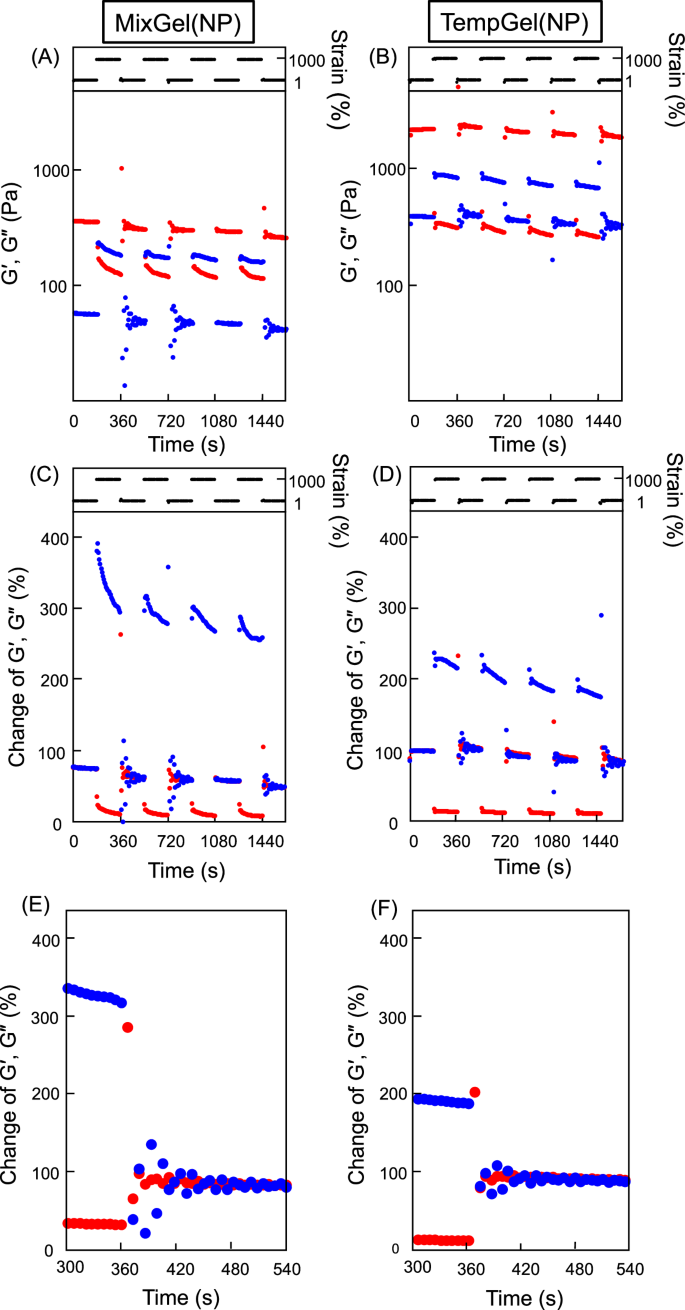

The boronic ester bond reformation efficiency was examined by subjecting the hydrogels to physical distortions. The hydrogels were placed on a rheometer plate, and the applied strain alternated between 1% and 1000% at 25 °C. When the strain increased from 1% to 1000%, the G’ and G’’ values became inverted, indicating structural breakdown of the hydrogels (Fig. 5). For MixGel(NP), both the G’ and G’’ values were restored approximately 100 s after the low strain was reapplied to the gel. However, the recovery rate, which reflects the changes in the G’ and G’’ values from those of the original hydrogel, decreased as the number of strain cycles increased, and was approximately 72% after four cycles. In contrast, TempGel(NP) demonstrated a better and faster recovery from physical stress. After four cycles, the recovery rate was approximately 90%, and G’ and G’’ were restored within 60 s. When the hydrogel physically disintegrated, some boronic ester bonds were forcibly cleaved. Once the physical stress was removed, boronic ester bonds reformed between the exposed PBA and nearby hydroxyl groups, allowing the hydrogel to regain its mechanical properties. In TempGel(NP), many hydroxyl groups were around PBA on the NPs, enabling the reformation of boronic ester bonds under static conditions. However, PBA and the hydroxyl groups on the hydrogel did not fully return to their original state after physical stress. Consequently, although TempGel(NP) exhibited better recovery than MixGel(NP), it also gradually showed a reduced recovery rate upon repeated physical bond cleavages, especially without thermal treatment.

A, B G’ and G’’ data and (C–F) variations in G’ and G’’ versus the original hydrogel for (A, C, E) MixGel(NP) and (B, D, F) TempGel(NP). The strain was alternated between 1 and 1000% every 3 min. Red and blue dots indicate G’ and G’’, respectively

The G’ (elastic modulus) and G” (loss modulus) values are normalized to the hydrogel’s original moduli (G0’) and (G0’’) before the gel was subjected to any mechanical strain. In this case, 100% indicates the mechanical properties of the hydrogel in its original state (at low strain, typically 1%) before any significant deformation occurred. These 100% values serve as a baseline, and subsequent G’ and G’’ measurements are expressed as percentages relative to this baseline. This means that any decrease or increase in G’ or G’’ due to the applied strain is shown as a percentage of the original value.

In Fig. 5C, the values at 0 s were less than 100% because the hydrogel had already undergone prior strain cycles before the measurement was taken. This suggests that after each high-strain cycle (1000%), the hydrogel partially recovers but the moduli do not return to their original values (G0’ or G0’’). In other words, the hydrogel retains some permanent deformation or loss in crosslinking efficiency after repeated cycles, which results in the moduli being slightly lower than the initial values (below 100%) when the strain is reduced to 1%. This partial recovery observed at 0 s reflects the ability of the hydrogel to recover its mechanical properties after multiple strain applications. This is consistent with the behavior of MixGel(NP), which demonstrated slower recovery and lower overall resilience than TempGel(NP).

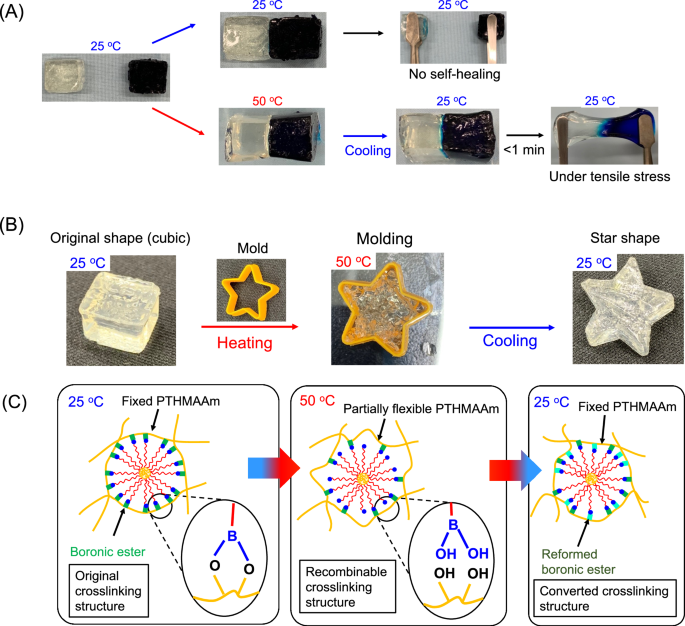

TempGel(NP) demonstrated greater thermal hysteresis in terms of its viscoelastic properties, allowing the formation of boronic esters on the NP crosslinker to be altered without impacting the elasticity of the hydrogel when the temperature changed. To verify the thermal recombination of the crosslinks, the self-healing ability of TempGel(NP) was tested by joining separate hydrogel pieces. The hydrogels were molded into cubes, and an adhesion test was performed by varying the temperature. Initially, the gel surfaces were brought into contact at 25 °C, but no adhesion occurred between the gels. The hydrogels were then heated on a hot plate at 50 °C (Fig. 6). When the hydrogels were heated, they softened, and the G’’ values increased significantly as the G’ and G’’ values shifted from 483 and 60 Pa at 25 °C to 390 and 124 Pa at 50 °C, respectively. Despite these changes, no adhesion between the surfaces was observed. However, after the hydrogels had sufficiently cooled to 25 °C, a connection was immediately established between the surfaces, indicating that the crosslinks on the hydrogel surface had reformed. This demonstrates that TempGel(NP) possesses a strong thermal self-healing ability. The thermoplastic properties of TempGel(NP) were subsequently demonstrated by the ability of the hydrogel to reform its crosslinks in response to temperature changes. A cubic hydrogel was heated to 50 °C to soften and then placed in a star-shaped mold. After cooling to 25 °C, the hydrogel retained its star shape once removed from the mold, as the new structure quickly stabilized as the hydrogel cooled. This finding shows that the original structure of TempGel(NP) can be easily altered via thermal treatment. Additionally, the thermoplasticity of TempGel(NP) can be triggered at room temperature for effective reshaping and reforming of the hydrogel’s crosslinks.

Photographs of TempGel(NP) at different temperatures. A Photographs of TempGel(NP) showing its A self-healing and B thermoplastic properties. The blue hydrogel was stained with methylene blue dye. C Possible effect of temperature on the formation of boronic ester bonds between PTHMAAm and PBA-NP. The boronic ester bonds are broken with increasing temperature and reform upon cooling to form new crosslinks. Because some boronic ester bonds remain between PTHMAAm and PBA-NP at 50 °C, PTHMAAm showed little diffusion from NP-PBA, allowing rapid and complete bond reformation at low temperatures

As previously mentioned, some studies have reported self-healing hydrogels that can connect to different hydrogels within seconds [5]. However, while these hydrogel connections form quickly, the reformation of bonds on the hydrogel surface relies on the diffusion of functional groups. Complete self-healing, which involves the full reformation of covalent bonds, is challenging because the limited diffusion of molecules or the steric hindrance of polymers can hinder coupling reactions on the hydrogel. In the case of TempGel(NP), molecular diffusion is significantly suppressed, which contributes to its high thermal hysteresis. Therefore, it is believed that complete formation of boronic ester bonds occurs immediately after cooling in TempGel(NP), endowing this hydrogel with self-healing and thermoplastic properties. Although this study does not provide direct evidence of the immediate thermal reformation of boronic ester bonds in TempGel(NP) because of the difficulty in measuring physicochemical changes in response to rapid temperature shifts, the high hysteresis observed in TempGel(NP) strongly suggests that boronic ester bonds can quickly and fully reform in response to temperature changes.

The tunability of hysteresis on the basis of PBA surface density allows hydrogels to be designed for specific applications that require varying extents of self-healing and thermoplastic behaviors. By varying the PBA density, the mechanical properties of the hydrogel can be tailored for specific applications. For example, high-density PBA hydrogels could be designed for biomedical applications that require strong, elastic materials, such as tissue scaffolding or wound dressings, where maintaining mechanical integrity is critical. Low-density PBA hydrogels, on the other hand, could be used in soft robotics or drug delivery systems, where flexibility and degradability are prioritized over mechanical strength. These applications benefit from the gel’s ability to undergo more significant deformation while still maintaining some structural cohesion. Hydrogels with higher PBA densities could be optimized for thermoplastic applications in which the material must rapidly adjust its shape in response to temperature changes while maintaining mechanical strength. This is particularly useful for reversible molding in soft robotics or shape-memory materials that need to return to their original configuration after deformation. The tunability of self-healing properties is another advantage. For applications such as wearable electronics or coatings, hydrogels with moderate to high PBA densities could provide the necessary durability and reparability in environments with frequent mechanical stress.

Future designs could use PBA surface density as a key tuning parameter to optimize hydrogels for specific functions. For example, gradient hydrogels with varying PBA densities across different sections could be developed for applications that require both rigid and flexible properties in different regions, such as in bioelectronics or adaptive materials. Further studies could explore the functionalization of PBA groups or the use of multivalent crosslinkers to increase the tunability of the hydrogel. By modifying the chemical structure of PBA or incorporating multivalent ligands, hydrogels can exhibit tunable responsiveness to different stimuli, such as pH, temperature, or mechanical force. This would expand the application potential to areas such as smart drug delivery systems or environmental sensors.

In this study, a hydrogel was created via template polymerization using boronic ester-coated nanoparticles. Since template polymerization is a widely applicable technique, other dynamic covalent bonds (DCBs) can also be used to prepare hydrogels. This research focused primarily on controlling the equilibrium of DCBs through temperature adjustments. However, the equilibrium of other DCBs can be influenced by different stimuli, such as pH or light. Therefore, the method proposed in this study has broad application potential for creating stimuli-responsive smart hydrogels. The key factors involved in producing a hydrogel with high hysteresis include the DCB equilibrium, a three-dimensional crosslinker with multivalent bonding characteristics and a densely packed structure generated via template polymerization.

Conclusion

In this study, we successfully developed a thermally responsive smart hydrogel via template polymerization of phenylboronic acid-functionalized nanoparticles (PBA-NPs) with [Tris(hydroxymethyl)methyl]acrylamide (THMAAm). The use of dynamic covalent bonds (DCBs) as crosslinks enabled the hydrogel to exhibit high thermal hysteresis, self-healing properties, and thermoplastic behavior. TempGel(NP) demonstrated a relatively constant storage modulus (G’) up to 60 °C, while the loss modulus (G’’) significantly increased with increasing temperature, indicating the tunable viscoelastic behavior of this hydrogel. In contrast, MixGel(NP) exhibited a more rapid decrease in G’ with temperature, indicating its lower structural stability. TempGel(NP) displayed 90% recovery of its initial storage modulus (G’) after four thermal cycles between 25 °C and 80 °C, as opposed to MixGel(NP), which recovered only approximately 72% of its original modulus. This indicates the superior thermal stability and self-healing capacity of TempGel(NP). The PBA density on the surface of the nanoparticles was crucial in determining the mechanical strength and thermal responsiveness of the hydrogel. A higher PBA density resulted in more efficient boronic ester bond reformation, contributing to a faster recovery and greater thermal hysteresis. The findings from this study suggest that template polymerization using nanoparticles offers a robust platform for designing hydrogels with tunable mechanical properties. Future research should explore the broader use of different dynamic covalent bonds (DCBs) and their impact on the thermal and mechanical properties of such hydrogels.

Experimental section

Preparation of TempGel(NP)

The PBA-NPs were synthesized following a previously established method [1]. Briefly, the block copolymer PBMA-b-PDMAPAAm-PBA (100 mg) was dissolved in acetone (1 mL), followed by the addition of water (1 mL). The acetone was completely removed under vacuum at room temperature using a rotary evaporator at 100 hPa. The polymer concentration was adjusted to 100 mg/mL by adding water to the block copolymer solution. The PBA-NPs (500 µl) and THMAAm (500 mg) were dissolved in water (1 ml), and the solution was bubbled with N2 gas for 10 min. Ammonium persulfate (APS, 1 mg) and N,N,N’,N’-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED, 10 µl) were then added to the mixture in an ice bath. After 10 min, the hydrogel was extracted from the vial and placed in a mold at 50 °C. Furthermore, the hydrogel was stained with methylene blue for visualization.

Measurement of viscoelasticity

The hydrogel was positioned on a rheometer plate (AR-G2, TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA), and the solution was covered with silicon oil to prevent water evaporation. Then, time sweep measurements were taken at a constant frequency (ω = 1 Hz) and strain (γ = 1 and 1000%) within the temperature range of 20–80 °C.

Self-healing and thermoplastic measurements

To verify the self-healing ability of the hydrogel, colored and noncolored cubic hydrogels were combined at 50 °C using a hot plate. Afterward, the hydrogels were allowed to cool to room temperature, and hydrogel fusion was visually examined after each process. Additionally, the thermoplastic properties of the hydrogels were assessed. First, the cubic hydrogel was kept at room temperature. The mixture was then heated to 50 °C until the hydrogel became soft, sealed in a star-shaped mold and subsequently cooled to 25 °C. The shape of the hydrogel was examined after it was removed from the mold.

Responses