Real world perspectives on endometriosis disease phenotyping through surgery, omics, health data, and artificial intelligence

Introduction

Endometriosis is an ancient disease with ancient treatments1 and is poised to benefit from modern technologies and continued innovation for accurate diagnosis, disease classification, and novel medical and surgical therapies2,3. It is a chronic, systemic, estrogen-driven disorder wherein disease lesions comprising tissue similar to the uterine lining (endometrium) develop outside the uterus—mainly in the pelvis and less commonly at extra-pelvic sites as the umbilicus, vagina, thoracic cavity, and gastrointestinal (GI) and genitourinary (GU) systems4,5. These ectopic lesions invade resident structures and elicit inflammation, neo-neuroangiogenesis, fibrosis, pain, and organ dysfunction6,7,8. Endometriosis affects 10–15% of reproductive age persons with a uterus, 50% of patients with chronic pelvic pain, and 30–90% with subfertility/infertility and is associated with multi-system comorbidities including irritable bowel syndrome, migraine headaches, depression, and inflammatory disorders2,9,10,11,12. Central to its pathophysiology are enhanced estrogen and diminished progesterone signaling, inflammation in the eutopic endometrium, disease in the pelvis, and systemically, and fibrosis in ectopic sites11,12,13,14,15.

Several theories exist to explain its pathogenesis16,17,18,19,20,21,22, and it is likely that different mechanisms occur in different patients. For example, dissemination of endometrial fragments and cells shed retrograde into the pelvis during menses (“retrograde menstruation”)23,24,25,26 is supported by recent evidence wherein somatic mutations in eutopic (within the uterus) endometrial epithelium are shared with endometriosis lesions19,27,28,29. However, as 98% of persons with a uterus have retrograde menstruation30 and only 10% have endometriosis, other mechanisms are likely operational. Other theories include benign metastasis of endometrial cells via uterine lymphatic drainage and vascular dissemination24, coelomic metaplasia of abdominal viscera and peritoneum mesothelium31, embryonic rests and endometrial and bone marrow-derived stem cell transformation32,33,34, iatrogenic introduction of endometrium into tissues and/or surgical sites, dysfunctional immune clearance of ectopic tissue11, and genetic, epigenetic, infectious, and environmental influences35,36,37,38,39,40,41.

The gold standard to diagnose endometriosis is surgical identification of lesions and suspected lesions and histologic confirmation of endometrial-like cells in lesion types. While clinical symptoms overlap with some other gynecologic disorders, imaging techniques, and AI-designed applications are increasingly complementing diagnostic evaluation2,42,43,44,45. The long latency (on average 7–11 years) from symptom onset to surgical diagnosis is mainly due to the absence of non-invasive diagnostic biomarkers and can result in disease and symptom progression, not uncommonly leading to irreversible organ damage as loss of kidney function, undertreatment, social isolation, and depression among affected individuals45,46,47,48,49.

Medical therapies for pain include reducing inflammation and estrogen action and/or synthesis, but these approaches have intolerable side effects for many patients, individual responses to specific medications are unpredictable, and 25–34% of patients exhibit no or poor response to these medical treatments48,49,50,51. Surgery is largely successful for pain, infertility, and subfertility management, although ~50% of patients have pain symptoms return within 2–5 years, requiring additional therapies48,49,50,51,52, and surgical outcomes are highly surgeon- and patient-dependent53. For infertile patients with endometriosis, medical-assisted reproductive approaches and/or surgery benefit most, although treatment responses are unpredictable48, and those with advanced versus early-stage disease54 have higher risk of poor pregnancy outcomes55. Overall, apart from surgical management following the revolution and evolution of minimally invasive and robotic surgery in the past 3–4 decades, there have not been major paradigm shifts in endometriosis care, including diagnosis, medical therapies, prevention, and long-term management2,3.

Thus, current unmet clinical needs comprise developing (1) non-invasive biomarkers to diagnose and stratify disease, (2) novel and personalized medical and surgical therapies targeted to individual lesion and lesion-niche interactions and pathophysiology, (3) prognostic outcome indicators for responses to therapies, risk of disease and symptom recurrence, and (4) ultimately, cure. Rapidly evolving single-cell and other advanced technologies are providing insights into endometriosis pathogenesis, pathophysiology, heterogeneity, and behavior, and can contribute significantly to fulfill these unmet needs. This manuscript focuses on endometriosis lesions and the centrality of the clinical context provided by surgeons, pathologists, gynecologists, and molecular and computational scientists to endometriosis lesion single-cell data generation, analysis, and interpretation. We focus on real-world perspectives of complexities of endometriosis diagnosis, lesion heterogeneity histologically, architecturally, and molecularly, and the importance of these to single-cell data analysis and integrative analyses of multi-omic datasets. With heterogeneity of lesion morphology and location, a more nuanced perspective of surgical assessment of lesions can provide insights into more detailed analysis of data derived from resected tissues. Other considerations for data interpretation, rigor, and reproducibility include disease symptoms (pain/infertility/both/neither), defining control groups, recruited subject clinical metadata including comorbidities, standard operating procedures for biospecimen processing, and designing computational pipelines for data analyses, sub-analyses, and surgical/pathology findings. We conclude with an eye to the future tapping AI and digital technologies to further advance the field. Information conveyed herein is based on peer-reviewed scientific publications, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, commentaries, and professional society statements from 1991 to 2024.

Endometriosis staging

Classification systems of endometriosis are based on surgical observations and/or fertility outcomes. These include the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) classification54, the ENZIAN classification56, the American Association of Gynecological Laparoscopists (AAGL) classification57, and the endometriosis fertility index (EFI)58. The most well-known is the rASRM classification wherein numerical scores for extent of disease and adhesions stratify disease stages from minimum (stage I) to severe (stage IV). The ENZIAN classification was developed to classify deep infiltrating endometriosis and focuses on retroperitoneal structures. Neither system predicts treatment outcomes nor correlates with severity of pain symptoms. The AAGL classification reports scoring intraoperative surgical complexity and correlations with patient-reported pain symptoms or infertility57. The EFI is the only system to predict non-IVF fertility outcomes in patients who underwent surgery for endometriosis58. The World Endometriosis Society (WES) 2017 consensus statement59 recommends using a “classification toolbox” that includes the rASRM system and the ENZIAN system for deep disease to improve disease classification. However, there is no classification system that is consistently used across the globe, and different systems are adopted according to clinical and surgical goals60,61.

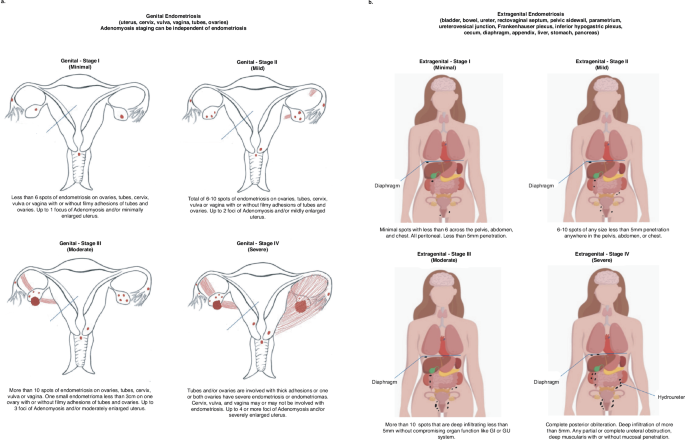

In contrast to the above, we developed a unique classification system62 that is more descriptive of disease appearance, location, and adhesions, and includes concomitant adenomyosis which is similar in cell composition and somatic epithelial mutations with endometriosis but located in the uterine myometrium63,64. Our classification (Fig. 1) describes reproductive organ (“genital”) (Fig. 1a) and non-reproductive organ (“extragenital”) (Fig. 1b) endometriosis. Genital endometriosis affects various parts of the reproductive system, including the uterus, upper cervix, vaginal fornix, fallopian tubes, and ovaries, and is classified into four stages: minimal (stage I), mild (stage II), moderate (stage III), and severe (stage IV) (Fig. 1a). Minimal or stage I disease is characterized by <5 spots with <5 mm penetration, minimal to no signs of adenomyosis, and no significant adhesions. Mild or stage II is characterized by 5–11 spots, also with <5 mm penetration, and minimal to mild adenomyosis. Moderate or stage III disease is defined as >11 spots of endometriosis with <5 mm penetration or endometrioma(s) <2 cm on a single ovary. There may be filmy adhesions between the tubes, ovaries, pelvic sidewall, and the anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs. Adenomyosis in this stage ranges from minimal to moderate. Severe or stage IV disease is depicted with genital endometriosis involving any number of lesions with >5 mm penetration (deep infiltration), including unilateral or bilateral endometriomas of any size, with or without rupture. There may be thick adhesions between the tubes, ovaries, the pelvic sidewall, and the anterior and posterior cul-de-sacs. In this stage, adenomyosis can range from minimal to severe. Additionally, adenomyosis alone can be categorized into 4 stages mentioned above without endometriosis noted,

a Genital endometriosis and its subtypes (minimum, mild, moderate, and severe). Depiction of genital endometriosis and its stages used the image of the female reproductive tract from: Cream Cake Diva/getdrawings.com (https://getdrawings.com/get-drawing#external-drawing-21.jpg), adapted and used under the Creative Commons License CC BY-NC 4.0. b Extra genital endometriosis (pelvic and extrapelvic) and subtypes (minimum, mild, moderate, severe). Depiction of extragenital endometriosis adapted the image used under the Shutterstock Standard License [Andrii Bezvershenko/Shutterstock.com (Stock Vector ID: 109207899).

Extragenital endometriosis (Fig. 1b) affects areas outside the reproductive organs, and is classified into four stages: minimal (stage I), mild (stage II), moderate (stage III), and severe (stage IV) and can be further classified as pelvic and extra pelvic62,65. Pelvic extragenital lesions are most commonly found on uterosacral ligaments and less commonly on the rectum, rectovaginal septum, ureters, and/or bladder66. Extra-pelvic structures include the gastrointestinal system67, lung and diaphragm5, liver68, genitourinary system4, abdominal wall, thoracic cavity, and/or nervous system5,62,65. The most common site of extragenital disease is bowel endometriosis, occurring in 7–37% of individuals with endometriosis67,69,70. The wide range in prevalence can be explained by inconsistent definition of bowel endometriosis. The latter primarily impacts the rectosigmoid colon, followed by involvement of the appendix, cecum, ileocecal valve, small bowel, and rarely the transverse colon62,67,69,70,71. Lesions can range from superficial serosal disease to deeply infiltrative disease invading into the muscularis or mucosa. Lower urinary tract endometriosis is less frequently found than bowel disease, followed by ureteral involvement. These lesions can appear as superficial peritoneal implants and do not affect the muscularis or mucosa. Via theories mentioned above, extragenital endometriosis can exist widely throughout the body.

Fibrosis is an important component in the progression of endometriosis12,15 and is further addressed below. Notably, different locations and niche environments of reproductive organ (“genital”) and non-reproductive organ (“extragenital”) lesions may contribute to altered pathophysiology of these distinct disease types, which is yet to be explored.

Endometriosis lesions

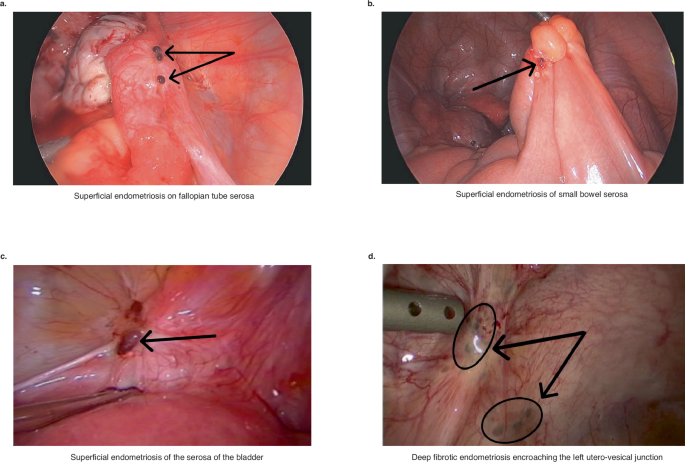

Endometriosis lesions are broadly categorized into 3 groups: superficial peritoneal endometriosis (SPE), ovarian endometriomas (OMA), and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE)6,11,72,73,74 (Figs. 2 and 3). They reside in different anatomic locations, display diverse structural architectures, variable steroid hormone responsiveness and invasive properties, and are highly heterogeneous in extracellular matrix (ECM) composition, abundance of endometrial-like epithelial cells, stromal mesenchymal cells (fibroblasts, stem cells), immune cells, vascular endothelium/smooth muscle/other mural cells, and extent of fibrosis. Despite their heterogeneity, there is evidence that all three lesion types derive from eutopic endometrium by retrograde menstruation and oligoclonal expansion, as several studies have shown that they share epithelial-specific somatic mutations with the intracavitary eutopic tissue19,27,28,29. Recently, abundance of KRAS mutations was found to correlate with lesion type: higher in patients with only DIE or only endometriomas (57.9%) and with mixed subtypes (60.6%) versus SPE (35.1% (P = 0.04))75. Moreover, greater mutational frequency was observed in rASRM stages II, III, and IV compared to stage I75. Although these data are highly supportive of eutopic endometrium as the source of pelvic disease, endometriosis outside the pelvis likely derives from hematogenous or lymphatic spread of endometrial tissue and cells and inside and outside the pelvis by stem and somatic cell trans-differentiation24,31,32,33,34. Overall, lesion types and subtypes and their cellular components and epithelial somatic mutations, coupled with surgical observations and clinical metadata are central to informing disease stratification and eventually identifying personalized and disease-specific therapeutic targets and prognostics for treatment responses and recurrence risk10,73,76. Single-cell technologies offer promise to contribute significantly to achieving these goals, which would be a huge step forward in the field. Herein, we focus on endometriosis lesions and lessons learned from recent single-cell studies, challenges in obtaining such data, and some real-world solutions.

a Superficial endometriosis on fallopian tube serosa. b Superficial endometriosis of small bowel serosa. c Superficial endometriosis of the serosa of the bladder. d Deep fibrotic endometriosis encroaching the left utero-vesical junction. Arrows point to the lesions.

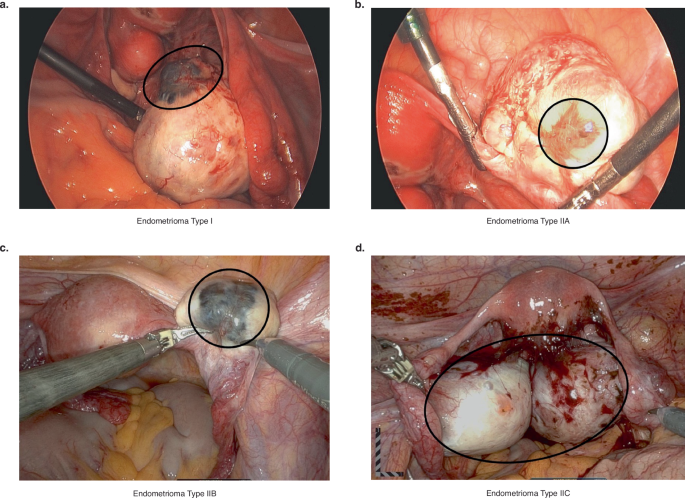

a Type I endometrioma. b Type IIA endometrioma. c Type IIB endometrioma. d Type IIC endometrioma. Black circles around the endometriomas have been drawn on the photographs to highlight the extent of the endometriomas.

Superficial peritoneal endometriosis (SPE)

Superficial disease is defined as lesions invading <5 mm into serosal structures77 and is commonly characterized by morphology, pigmentation (red, black, brown, yellow, white, clear), histology, and other features72,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87 (Fig. 2a–c). Endometriotic lesions are considered histologically “active” when glandular epithelium is proliferative or unresponsive to hormones with typical endometrial stromal fibroblasts. Endometrial glands, stroma, estrogen receptor-α (ERα) and progesterone receptor (PR)-A/B expression, and collagen fibers increase from colorless through red to blue-black lesions88. Red lesions are most highly vascularized and have higher VEGF expression and highest proliferative activity versus white lesions88, which appear as opacifications, sub-ovarian adhesions, yellow-brown patches, or circular peritoneal defects89,90,91. The black/brown or “gun-powder lesion” is a result of blood and hemosiderin deposits as well as glands, stroma, scar and other debris91. One report focused on a narrowly defined patient population and found a large overlap in proliferative activity and ER and PR expression across lesion color types, although differences were observed in lesion morphology, gland pattern, gland content, and adjacent stromal “reaction” of increased abundance of collagen and elastic fibers and smooth muscle bundles from red to brown to black to white lesions87. Based on these observations, red lesions are considered as fresh implants with progression to black/brown, yellow, and inactive white lesions72,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87. Atypical lesions include peritoneal defects, flame-like lesions, peritoneal petechiae, glandular lesions, and highly vascularized lesions89,91,92. In some cases, the only lesions observed at laparoscopy are those that are more physiologically active yet less obvious and are best described by Nezhat et al. in 199181, Donnez et al.90,93, and Nisolle et al.88. In a pilot study of patients with endometriosis and pelvic pain, Lessey et al.94 showed that microscopic disease, not readily apparent during surgery, could be detected in areas of methylene blue dye staining of the peritoneum after excision and scanning electron microscopy (SEM)94. Such “occult” lesions have had limited characterization at the molecular level, and this technique has not been widely adopted likely due to use of SEM in the workflow. Nonetheless, the presence of occult disease may contribute to persistent pain after medical and surgical therapies and disease “recurrence” after surgery and preliminary analysis suggests they may be detected by scRNA seq of seemingly unaffected peritoneum (see below).

SPE demonstrates heterogeneity of cellular steroid hormone receptors expression and niche fibrosis biomarkers92. A recent immunofluorescent study of 271 superficial peritoneal lesions with ≧1 endometrial epithelial gland and contiguous CD10+ stromal fibroblasts from 64 patients across the menstrual cycle revealed extensive heterogeneity of ERα and PR-A/B expression in these cell types and variable degrees of co-localization, even in the same patient95. Highest ERα and PR-A/B expression was in epithelium and stroma, respectively, during the menstrual versus other cycle phases95. These data underscore the importance of integrating ER and PR analyses into single-cell data analyses—especially in multiple cellular subtypes identified (also see below). Moreover, they underscore the challenges of medical therapies with e.g., progestins, and the promise of cell-specific targets which may differ lesion to lesion, leading to combined therapies for pain and/or infertility.

Fibrosis biomarkers—alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA)-positive myofibroblasts, smooth muscle bundles, and Type I collagen—have been consistently described over the past three decades as prominent features of superficial peritoneal lesions12,96,97,98,99,100,101,102, and subsequently there has been a call to redefine endometriosis to include its pro-fibrotic nature12. A recent study found low numbers of αSMA, type I collagen fibers, and CD45+ leukocytes, and CD68+ macrophages in SPE, in contrast to the adjacent tissue microenvironment with significantly more SMA and Type I collagen, depending on lesion location and gland morphology103.

Taken together, these data underscore the importance of lesion evolution, location, and niche environment, especially relevant to interpreting cell-specific signaling pathways, cell–cell communications and mediators thereof, classifying disease types and subtypes, and identifying and developing targets for therapeutics, diagnostics, and potentially for prognostic efficacy of responses to mono- or combined medical therapies. AI technology lends itself well here for pattern recognition, stage of disease, and standardization of care (see below).

Ovarian endometriomas

Ovarian endometriomas can be classified into Types I and II (Fig. 3). Type I endometriomas (Fig. 3a) develop from endometrial tissue that has implanted on the surface of the ovary. The ovarian cortex invaginates and blood accumulation results in growth of the cyst104,105,106,107,108,109. Type I endometriomas tend to be <5 cm and are difficult to remove due to their fibrous capsule that is densely adhered to the surrounding ovarian stroma106,110. On the other hand, Type II (Fig. 3b–d) endometriomas originate from endometrial implants entering existing functional cysts. They can be further categorized into Type IIA, IIB and IIC based on depth of invasion (<10%, 10–50%, and >50%, respectively)104,105,106,107,108,110,111,112.

Ovarian endometrioma cyst walls are primarily composed of fibrotic tissue especially in almost all endometriosis Type I and Type IIC and to a lesser degree Type IIA and Type IIB, with αSMA immunostaining confirming the presence of myofibroblasts12,104,105,106,107,108,111. In Type IIA and Type IIB endometriomas, the level of fibrosis correlates with invasion of endometrial stroma into the functional cysts. While fibrosis is consistently observed in ovarian endometriomas, histological examination reveals higher fibrotic content in deep infiltrating endometriotic lesions113. Platelet activation in ovarian endometriomas may induce fibrosis via TGF-β1 release and smad signaling pathway activation in endometriosis cells, which can be reversed with TGF-β1 blockade12,114. Fibrosis can extend into the ovarian cortex surrounding endometriomas and is associated with more atretic early follicles and lower ovarian follicle density compared to nonaffected ovaries115. A recent study demonstrated that the extent of endometrioma fibrosis positively correlated with dysmenorrhea severity but did not impact levels of anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), a marker of ovarian reserve; rather ovarian cortical fibrosis negatively correlated with serum AMH levels, supporting cortical fibrosis as a key driver of endometrioma-related impairment of the ovarian reserve116. Notably, intense inflammation in ovarian endometriomas117 can result in fibrosis and affect ovarian follicle function6,12. In a recent study, it was further confirmed that the presence of ovarian endometrioma(s) indicates a higher stage of disease correlating mainly with stage IV118.

Principal component analysis of microarray bulk gene expression data from endometriomas, SPE, and DIE119, revealed non-cycle-dependent gene expression profiles, and that endometriomas were significantly differentiated from the other two lesion subtypes and uniquely displayed ERβ (ESR2)-altered gene expression profiles after estrogen suppression versus non-treated controls. Overall, these data importantly suggest the role of the niche in lesion features and possible disease modifying targets for further therapeutic development. Single-cell data can further refine these targets and may reveal cellular and pathway heterogeneity supporting expanded multi-drug targets for disease management.

Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE)

DIE is defined as endometriosis infiltrating >5 mm into the peritoneum and serosa covering pelvic/abdominal organs120,121 (Fig. 2d). DIE can appear as nodularity of the rectosigmoid colon or rectovaginal septum, uterosacral ligaments, vaginal fornix and/or the bladder peritoneum122,123,124,125,126. It has been suggested that DIE can be classified into three types: (I) cone-shaped lesions that leave the pelvic anatomy intact, (II) adhesions covering lesions grossly disturbing pelvic anatomy, and (III) largely intact pelvic anatomy with the largest area of lesion beneath the surface120. Adenomyosis externa, which is characterized as endometrial tissue growing into the myometrium and extending outwards to surrounding pelvic tissue, can be included in type III DIE. Thus, despite similarities between DIE and adenomyosis externa, they are distinct entities126. Single-cell technologies are anticipated to inform the relationship between these two entities.

About 68% of deep infiltrating disease has been reported to be “active” versus 25–50% for lesions with <5 mm invasion, and 74% versus 38–57% were “in phase”, respectively, with the eutopic endometrium127. These data suggest more steroid hormone responsiveness in deep versus superficial disease. Undifferentiated and mixed gland patterns were found mainly in DIE, often with scant stroma, similar to endometriomas92. These features contrast with SPE which contains mostly well-differentiated gland patterns that are highly responsive to medical suppressive therapies92. We and others have found examples of fibrosis in deep infiltrating disease, where endometrial epithelium is present deep in fibromuscular tissue without the classic stromal surroundings81,93. DIE involves glandular epithelium within fibromuscular tissue, with the latter potentially originating from trans-differentiation of endometrial stromal cells rather than pre-existing muscle tissue, suggesting that the local tissue environment may react to ectopic endometrium, inducing fibrosis12,93,96,128,129,130. Present evidence suggests fibrosis may be a self-propagating event, indicating that although not always the case for all lesions, fibrosis can represent end-stage endometriosis12. Notably, a recent immunohistochemical study revealed higher expression of markers of fibroblast-to-myofibroblast trans-differentiation, smooth muscle metaplasia, fibrosis, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), epigenetic modifications, and ERβ, and less vascularity in DIE versus endometriomas. Single-cell analyses can further inform the diversity of cell and tissue features in DIE, important in disease classification and targeted therapies.

Recent single-cell analyses of endometriosis lesions

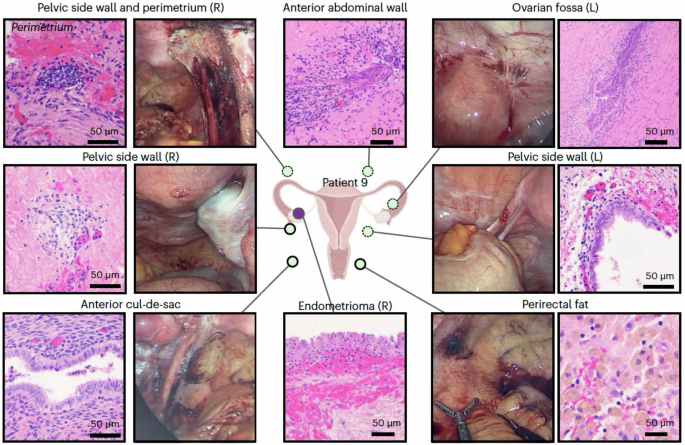

The transcriptome of intracavitary endometrium from volunteers and cadaveric subjects without endometriosis has been recently studied at single-cell resolution131,132,133,134. In addition, several studies have been published on scRNA seq of ectopic lesions and eutopic endometrium135,136,137,138,139,140,141, laying the foundation for comparisons with features of the intracavitary tissue of origin and also among lesion types. Figure 4 shows architectural and histologic heterogeneity of lesions131, underscoring significant lesion cellular components and unique niche environments identified at surgery and histologically. Major cell types identified in eutopic and ectopic endometrium using single-cell transcriptomics include epithelial, mesenchymal, vascular endothelial/smooth muscle/ mural, lymphovascular, immune (myeloid, lymphocytes), and stem/progenitor cells and subtypes, including ciliated, glandular, and luminal epithelium, numerous fibroblast subtypes, uterine natural killer (uNK), T, and B cells, and epithelial progenitors. These studies have identified a few novel cell types in lesions, as well as insights into cell–cell communications, lesion relatedness, and potential lesion evolution (see below). Table 1 provides a summary of recent endometriosis lesion single-cell transcriptomic studies wherein samples were obtained in different hormonal milieu (menstrual cycle phase, exogenous hormones), which is more extensively described in original data sources and in a recent review142.

The broad array of endometriosis lesions resected for research are shown here diagrammatically and histologically (hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) staining. From Fonseca et al.139, with permission.

Ma et al.135 sequenced 55,000 cells from 3 endometriomas and matched eutopic endometrium and 3 endometrium samples from controls without endometriosis in the proliferative phase. They found that immune cell sub-populations and fibroblasts were major contributors to a pro-inflammatory, angiogenic environment in endometriomas. T and uNK cell frequencies were lower, uNK cells more active, and macrophages (Mφ) were enriched in endometriomas versus the eutopic tissue, consistent with prior molecular analyses117. Thirteen fibroblast subtypes were identified with features of inflammation, fibroblast growth factor (FGF) stimulation, ECM reorganization, and EMT, further informing underlying processes observed histologically (see above). Moreover, eutopic endometrium from cases displayed a transitional state from normal to endometrioma, supporting the intracavitary tissue in the developmental trajectory of ovarian disease.

García-Alonso et al.132 leveraged publicly available bulk microarray transcriptomic data from endometriosis peritoneal lesions (GSE141549) to characterize lesion cell types applied in the context of their scRNAseq data generated from endometrium (basalis and full thickness (basalis and functionalis)) from volunteers in different cycle phases and cadavers (Table 1). Key findings included upregulation of SOX9+ in pre-ciliated epithelial cells of peritoneal lesions and a SOX9+/LGR5+ subset as in proliferative endometrium, and similar expression of progesterone-associated endometrial protein (PAEP) and SCGB2A2 (Secretoglobin Family 2A Member 2) in secretory cells and ciliated cell PIFO and TP73 as in peritoneum. That SPE display of basalis epithelial stem cell markers further supports the intracavitary origins of ectopic disease.

An atlas of endometriosis lesion cell populations was recently published from an extensive dataset of scRNA seq >370,000 cells from endometriomas, SPE and DIE lesions, endometrium, unaffected ovaries and peritoneum139. Samples were derived from 17 cases (9 with endometriosis alone; 8 with endometriosis and adenomyosis, uterine fibroids, and/or uterine polyps); 14 were cycling (7 proliferative, 7 secretory phases), and 3 on hormonal contraception. There were 4 controls without endometriosis: 3 postmenopausal and 1 perimenopausal, all with uterine fibroids +/− adenomyosis +/− uterine polyps, and all on hormonal replacement regimens. Major cell types identified in all samples included epithelial, mesenchymal, smooth muscle, endothelial, mast, myeloid, B, and T/NKT cells, and erythrocytes. All three lesion types and endometrium from cases versus control endometrium displayed different cell and molecular signatures, consistent with restructuring and transcriptional reprogramming in the lesions. Also, strikingly different transcriptomic signatures were noted in endometriomas versus SPE lesions, suggesting these are distinct disease entities, and SPE and DIE epithelium and fibroblasts displayed some distinct transcriptomic features and pathways, but structural genes were common, suggesting they are related and distinct from endometriomas. Interestingly, some histologically negative mesothelium had disease signatures, raising the possibility of occult abnormalities that may be precursors to lesion subtypes or reaction of normal peritoneum to different insults—physiological, biochemical, and/or perhaps genetic/epigenetic.

Tan et al.137 studied peritoneal lesions, endometriomas, and endometrium from cases and control endometrium—all from patients taking progestins, a common class of hormones for contraception and also to treat endometriosis-related pain48. The peritoneal lesions had similar cell compositions as endometrium but dysregulated innate immune and vascular components, in contrast to endometriomas that displayed distinct cell compositions137, supporting other studies of endometrioma cellular behavior as distinct from peritoneal disease. Overall, these data demonstrate that immune and vascular components of peritoneal endometriosis favor neo-angiogenesis and an immune tolerant niche in the peritoneal cavity.

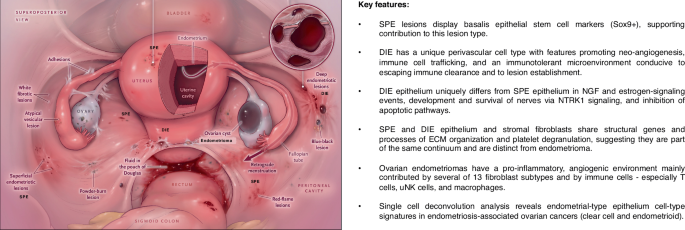

Key findings are summarized in Fig. 5 in the context of the 3 endometriosis lesion subtypes and their niche environments.

The image on the left illustrates the three major lesion types and subtypes (e.g., red lesions, black lesions) revealing their heterogeneity and anatomic locations. Image is from Zondervan et al.6 with permission. On the right are listed key features of endometriosis types (superficial peritoneal endometriosis (SPE), deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE), and endometriomas) and how they differ or share features with each other, based on studies on single-cell RNA-seq of lesions and endometrium described in the text.

Lessons learned from proteomic and metabolomic profiling studies

In the ongoing quest to uncover the causes of endometriosis, investigators have also increasingly utilized varied proteomic and metabolomic approaches. These have been pivotal for exploring the molecular mechanisms underlying endometriosis and for identifying candidate disease biomarkers of clinical utility. Their integration with transcriptomic data awaits further analyses.

Proteomic studies

Early proteomic research focused on analyzing the abundance of target proteins in blood (serum, plasma), revealing molecules such as CA-125143,144, CA-19-9145, inflammatory and oxidative stress mediators, hormones, cell adhesion molecules and angiogenic regulators as potential biomarkers of endometriosis146,147,148,149. However, these studies have yielded inconsistent results in terms of accurately diagnosing endometriosis, highlighting the limitations of a blood-based approach148,149,150,151. Consequently, researchers have shifted their focus towards profiling proteins in endometrial tissues and lesions.

Initial proteomic studies of endometrial tissues using targeted approaches identified diverse candidate biomarkers linked to critical processes such as cell cycle control, cell adhesion, and angiogenesis152. Newer non-targeted methods revealed a wider range of differentially expressed (DE) proteins in endometrial tissues of cases versus controls. For example, an early study using 2-D gel electrophoresis/matrix assisted laser desorption ionization (MALDI)-time of flight (TOF) mass spectrometry (MS) identified 48 proteins, including those with roles in stromal cell identity and oxidative stress, as consistently DE between endometriosis cases and controls, independent of menstrual cycle phase and disease severity153. Another study using a similar MS method identified 119 DE proteins in eutopic endometrium collected during the secretory phase of the cycle between stage II endometriosis cases versus controls154. DE proteins included molecules with important roles in apoptosis, immune responses, glycolysis, cell structure, and transcriptional regulation. More recently, liquid chromatography (LC)-MS/MS identified 5301 proteins in samples of eutopic endometrium obtained during the mid secretory phase of the menstrual cycle155. Of these, 543 proteins were DE between endometriosis cases and controls. DE proteins were enriched for pathways governing focal adhesion and PI3K/AKT signaling, implicating their roles in disease. These findings, along with others156,157, highlight the potential of proteomic analyses of endometrial tissues for uncovering disease mechanisms and identifying biomarkers.

Recognizing potential variations in the proteome across endometrial pathologies, investigations are conducting comparative studies. For instance, Zhu et al., using iTRAQ labeling combined with MS, identified 359 DE proteins upregulated in ovarian endometriotic cysts versus other ovarian tissues (i.e., ovarian cysts and normal ovarian tissues), with S100 calcium-binding protein A8 (S100A8) and A9 (S100A9) showing promise as predictors of postoperative recurrence158. Future investigations that delve deeper into the proteome of the endometrium and endometriotic lesions are a promising route to a better mechanistic understanding of this heterogenous disease and discovering biomarkers of its many forms, individually and as a group. In addition, the paired analysis of biopsies and blood (serum or plasma) has been proposed as an effective strategy to determine changes occurring on a tissue level that translate to serological biomarkers associated with the disease state. Early on, Zhang et al.159 applied 2-dimensional gel electrophoresis/MALDI-TOF-MS to identify 11 proteins in both endometrial tissue and serum that were DE in endometriosis cases versus controls. More recently, Manousopoulou et al.160 used a newer shotgun MS method to discover 1214 and 404 DE proteins (cases versus controls) in eutopic endometrium and serum, respectively. Among these, 21 proteins were DE in both matrices. They were enriched for carbohydrate/lipid metabolism and organ development, suggesting potential mechanistic links between these pathways and endometriosis. Additional research is needed to determine the ultimate value of applying MS-based global proteomic profiling methods to matched tissues and serum samples. Nevertheless, the concept of discovering biomarkers proximally in endometrial tissues and/or lesions and determining if they can be detected at altered levels in body fluids such as urine and blood is appealing.

While limited in number, the existing proteomic studies demonstrate their utility in uncovering DE proteins and related pathways in the context of endometriosis. Recent advancements, such as data-independent acquisition (DIA) MS, promise even higher sensitivity and reliability in protein identification. While not yet applied to endometrial tissues, a recent study of serum in endometriosis cases versus controls highlights DIA’s potential161. Furthermore, the application of single-cell proteomics will open new avenues for investigation of endometrial tissues and lesions162. Coupled with emerging high-dimensional proteomic imaging technologies, these single-cell approaches will enable incorporation of spatial information for a comprehensive phenotypic and functional proteomic mapping of the cellular architecture in solid tissue163. For example, in their recent study, Tan et al.137 combined spatial proteomics analysis using imaging mass cytometry with single-cell transcriptomics to characterize the cellular landscape of the eutopic endometrium. The results provided additional spatial context to proteomic data and emphasizing relationships between single cells and tissue architecture underlying disease histopathology.

Moving forward, the application of high resolution, quantitative-based proteomic methods along with study designs that incorporate possible confounding factors—such as the stage of the menstrual cycle164, severity165, lesion type166, and associated pain type167—is anticipated to enable robust identification of DE proteins, providing deeper insights into disease mechanisms and potentially clinically valuable biomarkers.

Metabolomic studies

The metabolome encompasses a wide array of metabolites, both endogenous—such as amino acids, organic acids, nucleic acids, fatty acids, amines, sugars, vitamins)—and exogenous, including environmental chemicals and pharmaceuticals168. Metabolomic approaches, including both targeted and non-targeted methods, have been used in endometriosis research to identify metabolic alterations linked with the disease’s pathophysiology and progression169,170,171. The majority of these studies have concentrated on endogenous metabolites in blood172. In limited studies, MS-based metabolomics has been utilized to profile endometrial tissues in the context of endometriosis. For example, Dutta et al.173 using proton NMR demonstrated differential levels of specific amino acids (e.g., lower alanine) and organic acids in endometrial tissues from women with endometriosis cases versus controls173. In another study, using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization high-resolution mass spectrometry (UHPLC-ESI-HRMS), investigators found that levels lipid metabolites—phosphatidylcholine, phosphatidylserine, and phosphatidic acid—differed in the eutopic endometrium of cases compared to controls174. These initial studies suggest that distinct metabolic disruptions in endometrial tissues and lesions could be integral to understanding the pathophysiology of endometriosis, offering new insights into molecular mechanisms contributing to changes at the cellular level.

Exogenous factors contribute to endometriosis, including infections and environmental contaminants. Recent reviews have underscored possible roles of the gut microbiome40 and the female reproductive tract microbiome and their metabolic products40,41 in endometriosis pathophysiology by modulating immune function and other mechanisms. The time is optimal to evaluate these early observations with disease lesion phenotypes and clinical metadata with the promise of revealing new treatment strategies. Moreover, a recent systematic review of 50 epidemiological studies highlighted positive associations between endometriosis and several environmental contaminants, including polychlorinated biphenyls, dioxins, phthalates, organochlorines, and bisphenol A175. These substances may disrupt tissue homeostasis through various mechanisms, such as acting as endocrine disruptors, modulating immune function, inducing oxidative stress and perturbing epigenetic processes176,177,178. Consequently, such disruptions can perturb endometrial cell functions and pathways that regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and decidualization179,180, leading to perturbations on the cellular and/or organ level. While largely unexplored, the use of emerging MS-based non-targeted approaches, utilizing not only blood181 but also endometrial tissues and lesions, provides great promise in identifying exogenous and endogenous factors that contribute to pathological changes in endometriosis and mechanisms of its pathogenesis.

Informative approaches in studying endometriosis lesions

The above studies, using single-cell and other advanced technologies, have provided huge insights into the heterogeneity of cell types/subtypes, unique clusters and signatures informing cell- and tissue-specific features, cell–cell communications, and pathways involved in cellular dysfunctions in endometriosis lesion subtypes and endometrium of patients with disease versus controls. It is anticipated that results across studies will further inform endometriosis lesion types and underlying pathophysiology. The future looks promising as advanced cell-specific transcriptomic and spatial localization provide insights into endometriosis and its comorbidities, and mass spectrometry-based methodologies enable quantification of thousands of proteins and metabolites in human blood and endometriotic tissues. However, significant hurdles remain, including sample/disease heterogeneity, diverse methodologies, differences in study designs, and complexities in data interpretation. These challenges contribute to inconsistent findings and hinder broader applicability, warranting careful consideration of their limitations for translating findings into clinical applications. Generating datasets from diverse populations, combined with the integration of -omic and clinical data, could ultimately provide a comprehensive understanding of disease pathways and manifestations, leading to the identification of reliable biomarkers for disease diagnosis and prognosis. However, these studies on a heterogeneous, hormone-sensitive disorder, also underscore real-world challenges and key informative approaches in conducting this type of research. Some of these include:

Lesion location and confirmation

Surgical phenotype data collection has been endorsed by the World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF) Endometriosis Phenome and Biobanking and Harmonization Project (EPHeCT)182. Documenting lesion locations, as described above, and proximity of lesions to each other are huge contributions of collaborating surgeons and warrant further study in how they inform data interpretation outcomes. Moreover, as lesions have multiple appearances, documentation of endometrial-like epithelial cells and stromal fibroblasts is important, although sometimes is challenging. The epithelium can be affected by hormonal changes, and some lesions (“stromal endometriosis”) contain scant or no epithelium183. Moreover, the stroma can be obscured by hemosiderin-laden/ foamy histiocytes, fibrosis, elastosis, smooth muscle metaplasia, and decidual change183, which can affect lesion identification, analysis, and data interpretation. About 60–80% of biopsied lesions have histologic confirmation of these two cell types85. If lesions are suspected but neither epithelium nor stromal cells are identified, pathologists often further section the lesions and may conduct immunohistochemical staining for the endometrial stromal fibroblast surface marker, CD10184,185,186. Recent computer-aided histopathological characterization of endometriosis lesions187 may further inform diagnosis. While a typical eutopic endometrial biopsy comprises ~200–300 mg of tissue, biopsied lesion volumes in SPE and DIE often results in very low cell yields, and the fibrous nature of endometriomas can limit sufficient non-fibrotic tissue-derived cells for sequencing and other analyses.

Standard operating procedures (SOPs)

We have adopted SOPs for endometrial and endometriosis tissue and peripheral blood biospecimen collection, processing, and storage, as described by Sheldon et al.178 and in the WERF-EPHeCT protocols188,189,190. Tissues are either flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, embedded in optimum cutting temperature (OCT) compound and/or formalin-fixed/paraffin embedded, depending on tissue volume and experimental design and goals. Frozen tissues and peripheral blood (plasma and serum) are stored at −80 °C until further use. As noted recently regarding unbiased approaches and advanced technologies for sequencing and the proteome and metabolome of endometrium and endometriosis lesions in the context of endometrial-based infertility, uniform protocols for sample collection and processing as described above and by WERF-EPHecT protocols188,189,190 are key for rigor and reproducibility from sample to sample and study to study191.

Determining hormonal status

As hormonal status at the time of sample acquisition is key to data interpretation of endometrial and endometriosis tissues, we assay estradiol (E2) and progesterone (P4) in serum collected on the day of surgery, complemented by histologic dating of the eutopic endometrium to determine menstrual phase cycle192,193, and record the subject’s last menstrual period and often menstrual cycle length for further context of cycle phase. Phase-specific transcriptomic signatures of select cell types are a huge advance in the field131,194. Samples from subjects on various hormonal treatments are a valuable cohort to study lesion responsiveness to select therapies. However, while ovarian-derived and synthetic hormones (e.g., progesterone and progestins, respectively) signal through common pathways, they also signal via unique pathways that could influence outcomes, as we have demonstrated in vivo and in vitro studies195,196,197,198,199.

Defining cases, controls, and rigor of de-identified metadata

Well-defined cases and control populations, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and clinical metadata are essential for all clinical studies and especially in designing and conducting studies and interpreting results of endometriosis lesions. Storage of these metadata in the REDCap database for ready access and updating during the study is often necessary as new information may be forthcoming. Key items include whether the diagnosis of endometriosis is accompanied by pelvic pain, infertility, subfertility, organ dysfunction, all of the above, or is asymptomatic; what the hormonal status of the subjects is (cycling, menopause, exogenous hormone usage at the time of tissue sampling and time interval since stopping these therapies). Other covariate phenotypic data include age, BMI, gravidity (i.e., prior pregnancy), race/ethnicity, medical, surgical, and family history, non-hormonal medication use, and comorbidities. The latter are particularly germane, as there is a high prevalence of common gynecologic disorders (e.g., uterine fibroids, adenomyosis, endometrial polyps, abnormal uterine bleeding) in cases (and controls). Furthermore, for controls, whether they have documented absence of endometriosis or presumed absence should be noted, as well as comorbidities. A comprehensive description of clinical and covariate phenotype data collection in endometriosis research was developed in the WERF-EPHeCT protocol in 2014200. Notably, while numbers of cells sequenced enrich the phenotypic features of individual cell types (Table 1), the numbers of subjects are, by comparison, low, and diversity of recruited cohorts is limited or not always documented. To date, as most studies either did not describe ethnicity or had a preponderance of White subjects, the data across ethnicities are limited and offer opportunity to close this gap in future research8.

Opportunities for the future

Integrating surgical, histologic, molecular, and genomic features

The cross-roads of decades of surgical, clinical, molecular, genetic, and epidemiologic research on endometriosis, and new data derived from advanced technologies at single-cell resolution offer an unprecedented opportunity to integrate these diverse data platforms and transform endometriosis disease phenotyping and elucidate further its pathogenesis and pathophysiology. For example, do cellular and sub-cellular features and processes differ in Type I vs Type II endometriomas, do they differ by location (e.g., “genital”, “extra-genital”, “extra-pelvic”), by nearest neighbor lesions, by ER and PR content and subtypes? Do they correlate with symptoms, treatment responses, are they impacted by comorbidities? As SPE, DIE, and endometriomas share common endometrial cellular origins, what is the role of the niche environments in which they are found, temporal effects of disease, and can this inform risk of developing disease and progression? How do cells within a niche and across niches communicate? What are the roles of genetics, dysbiosis of the gastrointestinal and female reproductive tracts, and environmental toxicants in these processes? It is hoped that more sophisticated disease stratification, including somatic genomic events201, will lead to discovery of non-invasive disease biomarkers, personalized and novel mono- or multi-target therapies for pain and/or infertility or organ dysfunction and disease modification, prognostic indicators for responses to medical and surgical therapies, and risk of disease and symptom recurrence—to enrich the lives of patients with endometriosis and eventually result in cure.

Integrative omics computational approaches for diagnostics and therapeutics

Integrative computational approaches hold significant promise in advancing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for endometriosis202. Single-cell transcriptomic datasets can be integrated with other molecular measures including proteomic, metabolomic, methylation as well as others, using approaches such as MOFA203,204 or DIABLO204 to identify common cell-type specific pathways and programs mis-regulated in disease. Importantly, while there is a high level of discordance between global transcriptomic and proteomic analyses at the level of individual mRNAs and their cognate proteins, there is a high degree of concordance at the pathway level, a principal recently demonstrated for human endometrium205. Also, unsupervised machine learning or clustering approaches can characterize lesions on the molecular level, and combined with precise phenotyping are anticipated to enable a better understanding of disease heterogeneity. Supervised machine learning approaches can be applied to these data to develop classifiers and predict which patients may have a particular outcome of interest. Furthermore, lesion-specific signals from transcriptomics and other types of molecular data can be used to advance drug discovery through both classical target-based approaches and more recent drug repurposing methods. In our own recent study206, we leveraged gene expression data to identify new therapeutic candidates based on transcriptional reversal. While the aforementioned study relied on signals from bulk transcriptomic data of eutopic endometrium, extending this work to leverage lesion data, especially on a single-cell level, is an exciting prospect.

Analysis of electronic health records

Analysis of electronic health records (EHR) data has contributed to enhancing our understanding of endometriosis disease phenotypes. For example, a study that implemented a clustering approach on the data of approximately 4000 endometriosis patients represented in a primary care clinical database found that women with endometriosis could be classified into six clusters according to the presence of comorbidities, including a cluster associated with fewer comorbidities, multiple comorbidities, anxiety and musculoskeletal disorders, type 1 allergy or immediate-type hypersensitivity, anemia and infertility, or headache and migraine207. Another work that utilized individual-level genotype and EHR data from the UK Biobank and genome-wide association statistics from multiple international resources revealed genetic and phenotypic associations of endometriosis with depression, anxiety, and eating disorders208. Combined analysis of clinical and molecular data can provide greater insights into endometriosis, although there has yet to be a study to date leveraging EHR with single-cell data for this disease. Such analyses could enhance our understanding of processes and/or mechanisms involved in endometriosis pathophysiology or disease presentation.

The power and promise of artificial intelligence (AI) for endometriosis

AI technology lends itself well to pattern recognition and using historical data to make predictions—features that are increasingly being applied in health care and translational research of complex diseases209,210. It holds great promise for screening and staging endometriosis with its complex classifications, varied clinical and molecular profiles, and unpredictable responses to therapies that are yet to be tailored for individual patients.

Recent technological advancements, such as the Nezhat Endometriosis Risk Advisor (EndoRA) application, highlight the growing role of AI in non-invasive screening44. EndoRA demonstrated a sensitivity of 93.1% in screening endometriosis in patients with chronic pelvic pain or unexplained infertility, although its specificity remains low (5.9%). This application’s free and accessible platform empowers individuals to identify their endometriosis risk, potentially leading to earlier diagnosis and better outcomes44.

With the recent advent and use of generative AI to democratize and standardize medicine, there may be opportunities for expedited progress in understanding, diagnosing, and managing endometriosis. For example, using large language models (LLMs) to analyze gene expression data could assist researchers with knowledge-driven candidate gene prioritization and selection which in turn could hasten the discovery of biomarkers and therapeutics211. In addition, analyzing molecular data combined with other types of data such as clinical records (e.g., electronic health records, patient registries) and environmental chemical and pollutant exposures data, could yield even greater insights into endometriosis including potential disease etiologies, mechanisms, and phenotypes43,212,213. While the current best LLMs may not be able to accurately diagnose patients across all diseases, future improved versions of LLMs could be used to analyze clinical records and assist clinicians in making potentially faster and more accurate diagnoses as well as recommending personalized treatment plans214,215. LLM-powered chatbots could provide support for patients affected by the endometriosis and education for individuals interested in learning more about this condition and even in pre-operative and patient education sessions216. Generative AI-empowered digital twins (DTs) could revolutionize drug discovery and development by enabling simulations across different biological models, from cells to clinical trials, although challenges remain including large data requirements, lack of straightforward interpretation, and regulatory oversight217. Addressing these obstacles as well as developing multimodal and foundation DT models could ultimately enhance drug development and personalized medicine217.

Democratization and standardization of endometriosis care from diagnosis to treatment

As multi-omics research and data integration proceed, and as minimally invasive and robotic surgery evolves, the principles of individualization and democratization of care and standardization of procedures underscore the necessity of enhancing global access to such procedures. Video-assisted surgery, pioneered by Dr. Camran Nezhat and his team, revolutionized the field, enabling complex operations with fewer complications and faster recovery times44. Moreover, digital surgery integrates robotics, data analytics, AI, enhanced visualization, and instrumentation, and technologies as image-guided ultrasound and augmented reality are progressing towards incision-less surgeries. Due to rapid advances in technology, tasks that once took days can now be done in hours, with attendant benefits for patients. These innovations offer pathways to a more equitable and advanced surgical future44.

Summary

In the “real world”, we, as a research and clinical community, have come a long way, together, to mine the mysteries of endometriosis. It is anticipated that multidisciplinary and integrative approaches will reveal features of endometriosis and its various subtypes that will transform non-invasive biomarker development to diagnose disease, identify cell-specific targets for personalized single or combined medical therapies for endometriosis pain and sub/infertility, and develop risk prediction models for disease and symptom recurrence. Additionally, as technology advances, we predict that surgical management, as well as medical management of endometriosis, will become standardized and democratized within the next 2–3 decades. Furthermore, incorporating AI and computational approaches is viewed as vital in analyzing multiomics and clinical datasets and patterns and improving understanding of endometriosis. Training the next generation of surgeons, clinicians, computational, epidemiologic, and wet lab researchers is a major goal to assure a pipeline of collaborators whose focus and efforts will result in improved well-being of patients affected by endometriosis and the ultimate goals of prevention and cure of this enigmatic disease.

Responses