Reassessing the involvement of the CREB pathway in the circadian clock of Drosophila melanogaster

Introduction

Circadian clocks emerged as a biological time keeping mechanism allowing organisms to orchestrate their physiology and behavior with the rhythmic occurrence of beneficial environmental conditions. The core molecular clock is comprised of transcriptional and translational feedback loops that allow self-sustained molecular oscillations with a period of about 24 h. One key feature of this system is to ensure alignment of internal time with the outer world by daily resetting of the clockwork for a continuous phase adjustment. Therefore, it is of great interest to understand how the system is able to integrate information about environmental cues with the endogenously generated oscillations. Environmental stimuli are perceived through different sensory organs, which convert this information into electrical signaling. But how are differences in membrane polarization transmitted through the cell to reach the nucleus and affect the core molecular clock? In the mammalian suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) pathway is known to play a crucial role in conveying light-input to the transcription of clock genes. The clock receives light-input through intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells that project onto the SCN1 and release glutamate and pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP)2. This leads to an increase in calcium and cAMP3,4, activating calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaMK) and protein kinase A (PKA), which then phosphorylate CREB5,6. Phosphorylated CREB then drives expression of light-induced genes like mPer1 through binding to cAMP response element (CRE) sequences in the promotor region7,8, which is a key driver for SCN entrainment9,10,11,12.

In Drosophila, there is also evidence for calcium and cAMP signaling being involved in the circadian system to modulate clock speed and synchronization to light:dark (LD) cycles. For example, on the one hand it was shown that dunce mutants (encoding a cAMP specific phosphodiesterase) exhibit short free-running periods and altered light-induced phase delays13. On the other hand, artificial modification of intracellular calcium signals in clock neurons resulted in dose-dependent lengthening of locomotor rhythms14. In addition, it was shown that alterations of calcium and cAMP levels in the central clock or the peripheral clock of the prothoracic gland affect the pattern of rhythmic eclosion15. A key trigger for cAMP signaling is the release of the neuropeptide Pigment Dispersing Factor (PDF), which plays an important role in synchronization of the neuronal network and acts through the G-protein coupled PDFR receptor to increase cAMP levels16,17,18. As known from mammals, the effects of calcium or cAMP signaling might be mediated by calmodulin dependent kinase II (CaMKII)14 or PKA, respectively13,17,18. An identified target of PKA activity is the stability of the core clock proteins TIMELESS17 and PERIOD18 but it is not clear if this is mediated via Creb. Based on parallels to the mammalian system and the fact that putative CRE sequences are present in the promoter regions of both timeless19 and period20, this hypothesis seems reasonable.

The Drosophila genome encodes two Creb proteins, namely CrebB (homolog of the mammalian CREB) and CrebA (homolog of the mammalian CREB3L/OASIS), which both belong to a family of 27 identified basic leucine zipper proteins21. CrebB has a well-established role in long-term memory (e.g. reviewed in22) and CrebA was found to function in embryonic development23 and regulation of the secretory pathway24. CrebB is expressed within the clock neurons, including the adult s-LNv pacemaker neurons (Fig. S1) and CrebB protein levels were found to cycle in larval LNvs and adult l-LNv25,26. Similarly, CrebA protein cycles in larval s-LNvs, and is rhythmically transcribed in adult s-LNv27,28. Moreover, CRE-luciferase reporter activity was also shown to oscillate in a circadian fashion, and to be modulated by per mutations20,29. Regarding their potential role in providing input to the circadian system, knockdown of CrebA was reported to cause arrhythmicity or period lengthening15, whereas the CrebBS162 mutation leads to arrhythmicity or period shortening of locomotor behavior20. Additionally, CrebBS162 was found to severely interfere with rhythmic oscillations of a period-luciferase reporter20. However, these results were obtained with physically small, hemizygous escaper males harboring the otherwise lethal CrebBS162 mutation, pointing to potential pleiotropic effects of this allele20. Two other studies highlight the possibility that Creb might link neuronal activity and clock gene transcription: Firstly, Eck et al.25 showed that artificial depolarization of clock neurons during the delay and advance zone, where the circadian clock is sensitive to phase shifts, caused a parallel increase of PER and Creb levels in l-LNvs. Secondly, Mizrak et al.26 found that hyperexciting or hyperpolarizing LNvs leads to a morning or evening-like transcription profile, respectively. They revealed that many genes, including CrebA and CrebB, are sensitive both to circadian regulation and neuronal activity, and frequently show an enrichment of CRE sequences in their promoter regions. Moreover, overexpressing CrebA and CrebB caused period lengthening26 and CrebB was also identified as rate-limiting substrate of the nonsense-mediated mRNA decay pathway that sustains circadian behaviors30. Furthermore, the CREB binding protein (CBP) has also been shown to affect behavioral rhythmicity and clock gene expression by regulating CLOCK/CYCLE-dependent transcription, though not yet conclusive if as a positive or negative regulator31,32.

Considering these findings, it appears likely that Creb indeed plays a conserved role in the circadian clock, although definite evidence is still lacking. Here, we aimed to further elucidate the involvement of Creb in the circadian clock of Drosophila by using a combination of advanced genetic tools, behavioral assays and bioluminescence recordings. To our surprise, our findings yielded no evidence supporting a role for the Creb pathway in the Drosophila circadian clock.

Material and methods

Flies

Flies were housed in plastic vials on standard fly food (0.7% agar, 1.0% soy flour, 8.0% polenta/maize, 1.8% yeast, 8.0% malt extract, 4.0% molasses, 0.8% propionic acid, 2.3% nipagin) under a 12 h:12 h LD cycle at 60% relative humidity. Fly stocks were kept at 18 °C and crosses were reared at 25 °C. All flies used in this study are listed in Tab 1.

Generation of CrebA-KO

For cell type specific CRISPR knockout of CrebA, a fly line expressing Cas9 and multiple gRNAs from a single tRNA::gRNA transcript under UAS control was generated, as described in ref. 33. CRISPR Optimal Target Finder34 was used to select three target gRNA sites within exon three and four, upstream of the predicted basic-leucine zipper domain. Overlapping PCR primers encoding the gRNA sequences (bold and underlined) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Cloning of the construct was carried out based on the pCFD6 cloning protocol on http://crisprflydesign.org. Primer pairs CrebA_PCR1_F / CrebA_PCR1_R and CrebA_PCR2_F / CrebA_PCR2_R were used on the pCFD6 template (Addgene #73915) using high-fidelity Phusion polymerase (NEB). The two resulting PCR products were gel purified using Roti-Prep Gel Extraction (Carl Roth) and assembled with BbsI-linearized pCFD6 backbone using In-Fusion HD Enzyme Premix (Takara Bio). The assembly mixture was transformed into competent Stellar cells (Takara Bio) and transformants were screened in a colony PCR for inserts of the correct size using OneTaq Master Mix (NEB) with primers pCFD6_F and pCFD6_R. Plasmids were extracted using Roti-Prep Plasmid Mini (Carl Roth) and sent for sequencing with the pCFD6_F primer to GATC Eurofins Genomics. For transgenesis, plasmids were purified using Plasmid Plus Midi (QIAGEN) and injected into w, vasa ɸC31; attp40; attP2 embryos. G0 offspring was batch crossed to w; Sco/CyO; MKRS/TM6B and F1 offspring was screened for red eyes and individually crossed to the double balancer line again. Flies carrying the construct on the third chromosome were combined with UAS Cas9.P2 on the second chromosome.

CrebA_PCR1_F

5’ TTCGATTCCCGGCCGATGCATCGTGTTAGATCCGCGACGGGTTTCAGAGCTATGCTGGAAAC

CrebA_PCR1_R

5’ ACTTCTCAAGCGAGCAGCTCTGCACCAGCCGGGAATCGAACC

CrebA_PCR2_F

5’ GAGCTGCTCGCTTGAGAAGTGTTTCAGAGCTATGCTGGAAAC

CrebA_PCR2_R

5’ GCTATTTCTAGCTCTAAAACTACGGGTCAGCCGCACCGCTTGCACCAGCCGGGAATCGAACC

Locomotor activity

Behavior experiments measuring locomotor activity were carried out using the Drosophila Activity Monitoring (DAM) system (TriKinetics). One to three days old male flies were loaded into small glass tubes, supplied with food (4% sucrose and 2% agar) and plugged with cotton. Monitors were kept in environmentally-controlled incubators (Percival Scientific) with white light bulbs. All behavior experiments were performed at 25 °C. For behavioral controls Gal4 drivers and UAS lines were crossed to y w; ls-tim.

For rhythmicity and period analysis, flies were entrained to 12 h: 12 h LD for three days and then released into DD for seven days. Data analysis was performed using the Fly-Toolbox in MATLAB35. For behavior quantification flies were manually scored as rhythmic or arrhythmic based on single actograms and rhythmicity analysis. Average period length and rhythmic strength (RS) were calculated from values given by autocorrelation analysis. Differences in period and RS value of experimental flies were calculated for both parental controls and tested for statistical significance using a two-sided permutation t-test.

For phase shift analysis, flies were entrained to a reversed 12 h: 12 h LD for five to seven days and then subjected to a light pulse before being released into DD for five to seven days. The light pulse was carried out by shifting monitors to another incubator with lights on for 15 minutes. One group of flies received the light pulse at ZT15 and one group at ZT21, while the control group was not exposed to light. Data analysis was performed using the Fly-Toolbox in MATLAB to determine the phase of rhythmic flies on the first day of DD and on the second to fifth day of DD. Average phase differences were plotted using estimation statistics36.

For re-entrainment analysis, flies were kept under an initial 12 h: 12 h LD for three days, which was then phase shifted by 5 h. Flies were kept six more days under the second LD before being released into DD for six days. Data analysis was performed using the Fly-Toolbox in MATLAB to generate population actograms and histograms.

Bioluminescence assays

Bioluminescence Luciferase expression in individual flies expressing the plo or BG-luc period reporter gene was measured as described in ref. 37. For parental controls Gal4 drivers and UAS lines were crossed to Canton S. One to three days old male flies were individually placed into every other well of a 96-well plate filled with 100 µl of luciferin-containing food (5% sucrose, 1% agar and 15 mM luciferin) and covered with a clear plastic dome. Bioluminescence was measured every 30 min using a Packard TopCount Multiplate Scintillation Counter (PerkinElmer) for three days in LD, followed by three days in DD at 25 °C. Data were plotted using the Brass Macro (Version 2.1.3) in Excel38. Bioluminescence rhythms in groups of flies in DD were measured using LABL (Locally Activatable BioLuminescence). For a detailed description of this method see ref. 39. In brief, expression of Flipase using the indicated Gal4 drivers allows anatomical restriction of the firefly luciferase reporter (Luc2, Promega). D-luciferin potassium salt (Biosynth) was mixed with standard fly food, or 5% sucrose, 1% agar to a final concentration of 15 mM in Drosophila culture plates (Actimetrics). Luminescence of 15 flies per plate was measured every 4 min for 7–8 days in DD at 25 °C with a LumiCycle 32 Color (Actimetrics). Analysis software was used to normalize the exponential decay, data were exported into .csv files (Actimetrics) and locally written python code was used to organize luminescence data into 30 min bins (LABLv9.py; www.top-lab.org/downloads), and to quantify periods of oscillations using a Morlet wavelet fit (waveletsv4.py; www.top-lab.org/downloads). Data were plotted using Graphpad Prism 10.

Immunostaining

First, the tim27-Gal4 bearing chromosome 2 was recombined with tub-Gal80ts using standard genetic crosses. Recombinant tim27-Gal4, tub-Gal80ts flies were then crossed to the CrebB-KO [FRT-eGFP-CrebB-FRT]; UAS Flp flies at 18 °C (Gal80ts is active). F1 flies were either maintained at 18 °C, or shifted to 29 °C (to deactivate Gal80ts) for five days. Flies were fixed in 4% PFA for 2.5 h at room temperature (RT). After fixation, the samples were washed 6 times for at least 1 hr with 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) with 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBST) at RT. The brains were dissected in PBS, then blocked with 5% goat serum in 0.1% PBS-T for 2 h at RT and stained with pre-absorbed rabbit anti-PER (1:10000)40 and mouse anti-GFP (Sigma G6519, 1:200) in 5% goat serum in 0.1% PBST for at least 48 h at 4 °C. After washing 3 times by PBST, the samples were incubated at 4 °C overnight with goat anti-mouse AlexaFluor 488 nm (1:500) and anti-rabbit AlexaFluor 647 nm (Molecular Probes) in PBST. Brains were washed 3 times in 0.1% PBST before being mounted in Vectashield. The images were taken using a Leica SP8 confocal microscope, and processed using GIMP41.

Results

Loss of CREB does not affect rhythmicity or period length of locomotor activity

In order to investigate the effects of CrebB and CrebA on the circadian clock while circumventing issues with lethality of mutant flies, we opted for cell type specific gene knockout. For CrebB we used flies with a conditional flip out allele, which allows excision of the whole gene locus42, while for CrebA we generated flies carrying a conditional CRISPR construct, that enables gene disruption by frameshift mutations33, all under the control of the Gal4 UAS system (Table 1). We knocked out CrebB or CrebA either in all clock cells using tim27-Gal4, in all clock neurons using Clk856-Gal4, or specifically in LNvs using Pdf-Gal4, and recorded locomotor behavior of these flies in standard light dark cycles (LD) and constant conditions (DD) at 25 °C.

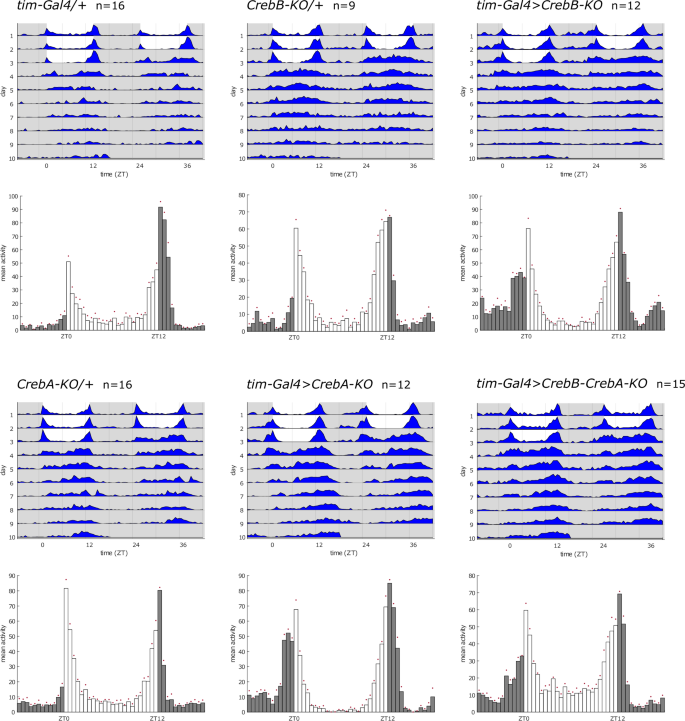

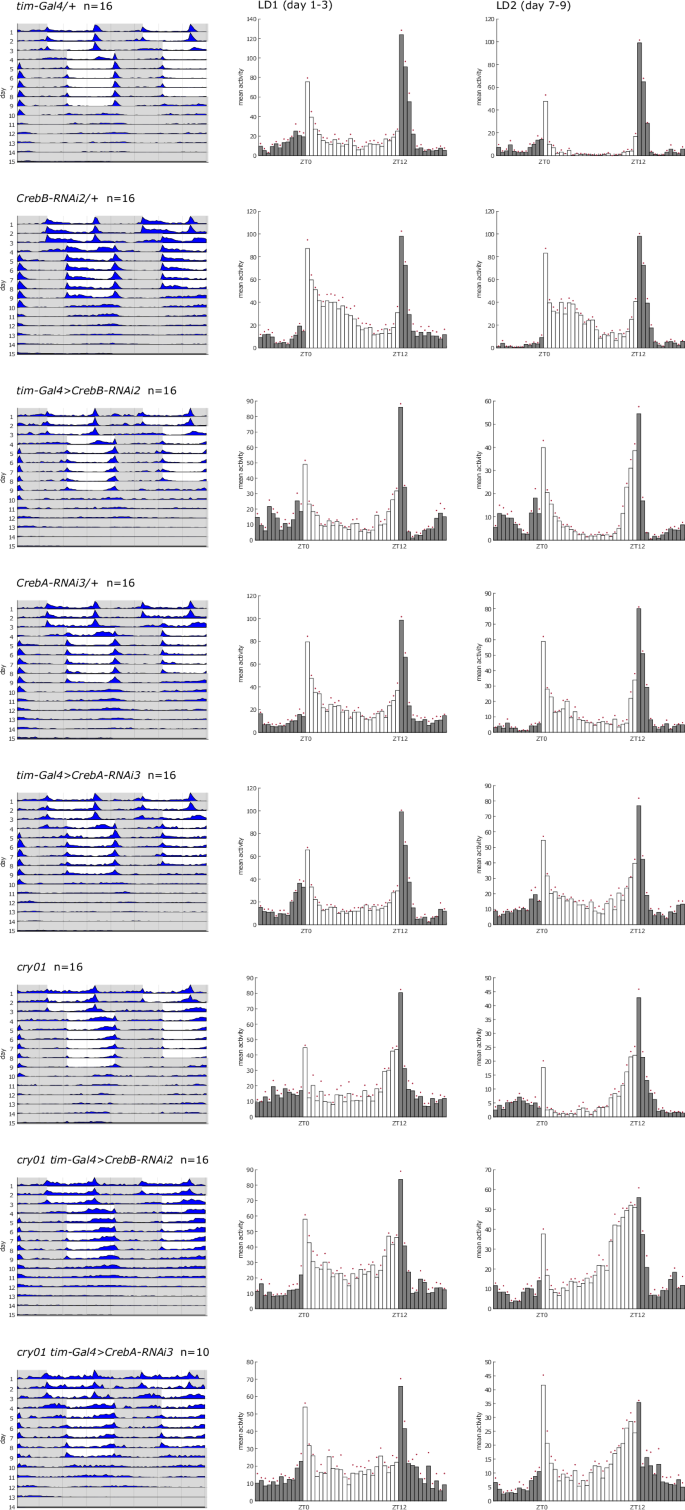

Representative examples of actograms and histograms are shown in Fig. 1, while the quantification of DD behavior is provided in Supplementary Table 1. Despite the lack of CrebB or CrebA, most flies showed rhythmic locomotor activity, only tim-Gal4>CrebB-KO and Pdf-Gal4>CrebB-KO knockout led to very mildly reduced rhythmicity of 86 and 79%, respectively. Rhythmic flies also exhibited a normal period length that did not differ significantly from parental controls, for example 24.5 h for CrebB knockout and 24.4 h for CrebA knockout using tim-Gal4. To evaluate if displayed rhythms of knockout flies differed in their robustness to that of control flies, the rhythmic strength (RS) was taken into account. However, the RS value of knockout flies was not significantly reduced, and in some cases (tim-Gal4>CrebA-KO) even exceeded control values (Supplementary Table 1). Since CrebB and CrebA both belong to the same gene family and have both been attributed a role in the circadian clock, we aimed to rule out redundant or compensatory effects. As both conditional knockout constructs utilize the Gal4 UAS system, it was feasible to generate a CrebB CrebA double knockout line. Still, removing both proteins from all clock cells did not cause significant alterations in rhythmicity, period length or RS value (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1).

Representative double-plotted actograms and histograms showing average locomotor behavior of indicated genotypes. Behavior was recorded for three days in 12 h : 12 h light dark cycles (LD) and seven days in constant darkness (DD) at 25 °C. White area in actograms / white bars in histograms = lights on, gray area in actograms / gray bars in histograms = lights off. For behavior quantification refer to Supplementary Table 1.

To further validate our results with a different genetic approach, we investigated the effects of CrebB and CrebA knockdown, using two and three independent RNAi lines, respectively. Here we also included the double knockdown of CrebB and CrebA, using three different combinations of these RNAi lines. As seen before, rhythmicity in free running conditions was not reduced and the RS value was never significantly decreased compared to controls (Supplementary Table 1). Average period length was significantly shortened in three cases, with 23.3 h for Clk856-Gal4>CrebA-RNAi1, 23.1 h for Clk856-Gal4>CrebB-RNAi2 and 23.7 h for Pdf-Gal4>CrebB-RNAi2 flies (Supplementary Table 1). However, all these changes were of a mild nature of less than one hour and we could not make out any consistency between driver lines and knockouts/-downs.

Furthermore, inspection of the histograms revealed that loss of CrebB or CrebA generally did not affect synchronized behavior under standard 12 h : 12 h light dark cycles. Flies lacking CrebB or CrebA in all clock cells exhibited the typical bimodal pattern with a clear morning and evening anticipation. We noted that knockout of CrebB led to a mild activity increase during the night, and that the morning peak of both CrebB and CrebA knockout flies seemed more pronounced and slightly phase advanced compared to controls (Fig. 1).

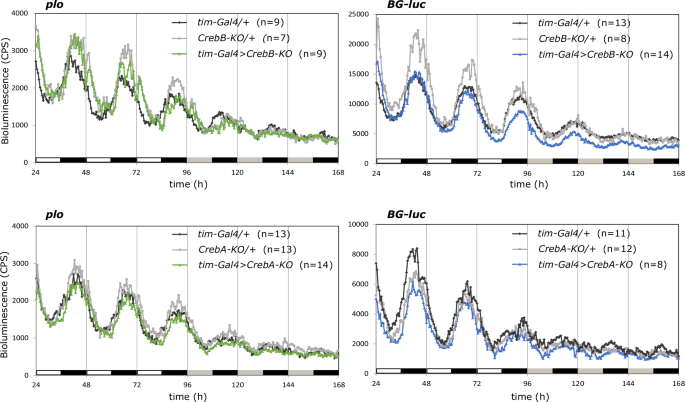

Loss of CREB does not affect oscillation of core clock gene period

Next, we aimed to complement our behavioral findings, reflecting an output of the circadian clock, with an approach to assess oscillations of the core molecular clock itself. In the mammalian SCN, CREB directly mediates transcription of mPer1 in response to light7 and in Drosophila the promoter region of period also harbors three putative CRE sites20. Concordantly, the CrebBS162 mutation strongly diminished rhythmic expression of the plo period–luciferase reporter (reflecting period transcription) in constant darkness, while cycling of the BG-luc reporter (reflecting PERIOD protein) was intact but reduced in amplitude and phase advanced compared to wild type20. We made use of the same reporter genes and tested the effects of clock cell restricted knockout of CrebB and CrebA on period cycling. Average bioluminescence measurements recorded from individual whole flies during three days of LD and three days of DD are shown in Fig. 2. In accordance with behavioral results, expression of plo was not altered in cycling pattern or amplitude upon knockout of CrebB or CrebA. Likewise, there was no effect on the BG-luc expression pattern. Expression levels of the reporter dropped slightly in CrebB knockout flies on the third day of LD, however this did not affect the amplitude of cycling.

Bioluminescence measurements of indicated genotypes expressing either plo (reflecting period expression) or BG-luc (reflecting PERIOD protein) luciferase reporter genes. Plots show average counts per second (CPS) of flies individually sampled every 30 min using a Packard TopCount Multiplate Scintillation Counter. Flies were recorded for three days in 12 h : 12 h LD and three days in DD at 25 °C. White and black bars = lights on and lights off, gray and black bars = subjective day and subjective night.

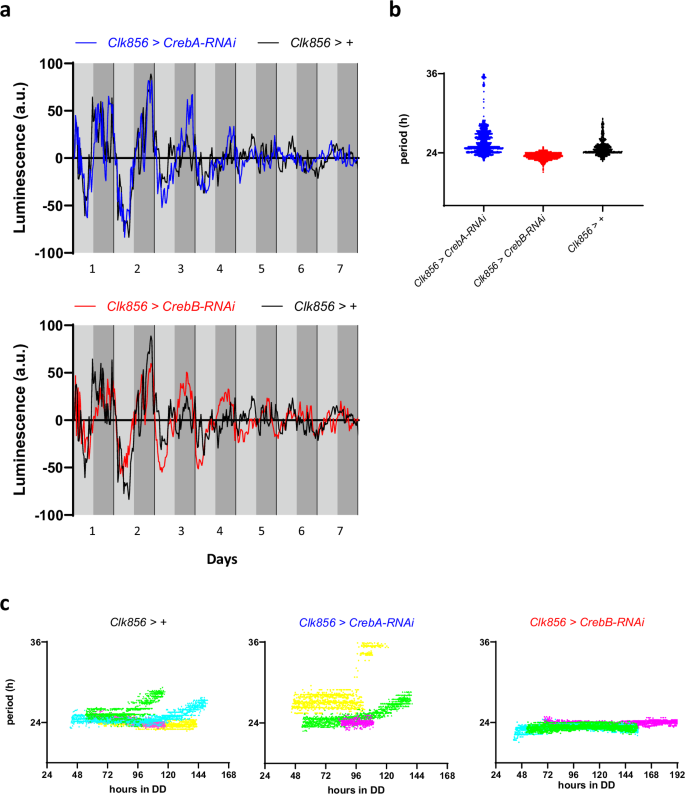

Since these measurements mostly report signals from peripheral clocks, we then made use of a recently developed tool termed Locally Activatable BioLuminescence (LABL) that allows cell type specific expression of a period-luciferase (per-luc) reporter39. We used Clk856-Gal4 to specifically restrict reporter expression and Creb manipulations to clock neurons only. CrebA or CrebB expression was downregulated by the respective UAS-RNAi constructs present in the same flies (Fig. 3). 15 flies of each genotype kept together in a dish containing luciferin fortified food were measured for 7–8 days in DD at 25 °C and each genotype was tested at least in three independent experiments (Fig. 3). Similar to the results obtained with the pan clock cell drivers described above, no effects of CrebA or CrebB knockdown on clock neuronal per-luc expression were observed. Control, CrebA-RNAi, and CrebB-RNAi flies showed robust LABL oscillations for the first three days, and lower amplitude rhythms until the end of the experiment (Fig. 3a). Average period length was close to 24 h for all three genotypes, although some of the control and CrebA-RNAi flies showed long period rhythms (Fig. 3b). When looking at period changes during the course of the experiment, we noted that both control and CrebA-RNAi flies had stable 24 h periods for the first 2–3 days of the experiment but showed a tendency to increase their period length afterwards, at least in some of the experiments (Fig. 3c). While we have no explanation for this drift in period-length, it explains the observed longer average periods observed in the same genotypes (Fig. 3b). In contrast, CrebB-RNAi flies consistently showed stable ~ 24 h periods during the entire length of the experiments (Fig. 3c). We therefore conclude that both Creb genes do not influence rhythmic per-luc expression in the clock neurons.

LABL analysis of flies expressing RNAi constructs for CrebA and CrebB in all clock neurons. Male flies with the genotypes w; Clk856-Gal4/LABL; UAS-CrebA-RNAi3/UAS-FLP, w; Clk856-Gal4/LABL; UAS-CrebB-RNAi2/UAS-FLP, and w; Clk856-Gal4/LABL; UAS-FLP/+ as control, were measured in a LumiCycle luminometer (Actimetrics) for 7-8 consecutive days in DD at 25 °C. a Bioluminescence oscillations of LABL flies expressing per-luc in all clock neurons plotted over time. Oscillations of CrebA-RNAi (top, blue) and CrebB-RNAi (bottom, red) flies from one representative experiment are plotted over time in comparison to the same control (black). Light grey shading indicates subjective day, dark grey subjective night, respectively.b Average period of per-luc oscillations in clock neurons Colored dots indicate period values of significant curve fits between 16 and 36 h incorporating data from all experimental repeats (n = 3 for CrebA-RNAi and CrebB-RNAi, n = 4 for control). c period changes of per-luc oscillations calculated by Morlet-wavelet-fitting over time (Material and methods39). Genotypes same as in A and B. Colored dots indicate significant periods as in B, with different colors representing independent experimental repeats. Periods with confidence intervals of 25% or less were omitted.

Loss of CREB does not affect synchronization to light

In the mammalian system CREB relays photic information to the circadian clock and is therefore also directly involved in phase shifting the clock in response to a light pulse43. In accordance with this, in Drosophila a temporal overlap in the increase of Creb and PER levels after depolarization of l-LNvs was found, both in the delay and advance zone where phase adjustments can occur25. In addition, it was shown that both CrebB and CrebA expression is sensitive to LNv membrane excitability and that there is an enrichment of differentially regulated genes harboring CRE sequences26. Thus, it is hypothesized that Creb might link neuronal activation and the molecular clock and function as molecular gate to regulate LNv responsiveness to entrainment cues.

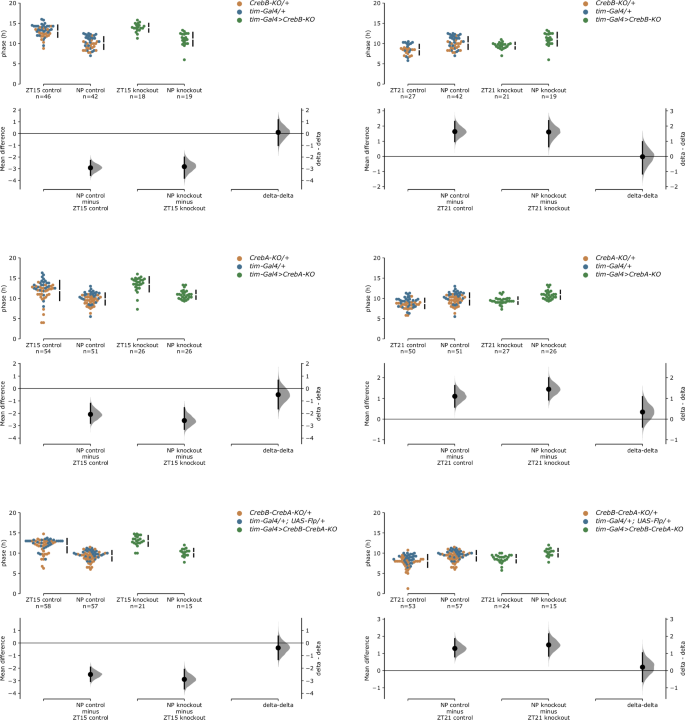

To test if CrebB or CrebA do indeed play a role in the phase adjustment in response to a light pulse in Drosophila, we subjected the single and double knockout flies to an anchored phase response experiment. For this, flies were entrained to a LD cycle and then either received a light pulse at ZT15, at ZT21, or no light pulse (NP) during the last dark phase of LD, before being released into DD. Phase measurements were performed on the second to fifth day of DD, where phase resetting would be completed, as well as on the first day of DD, to identify potentially more subtle effects. Figure 4 shows individual phases on the first day of DD of knockout flies and pooled parental controls for the three different treatment groups as well as the average phase shifts and the difference between them (delta-delta). All genotypes were able to significantly delay and advance their phase in response to the light pulse compared to their non-pulsed controls. On average CrebB knockout flies delayed their phase by 2.8 h and advanced by 1.6 h, while their parental controls exhibited a slightly stronger but not significantly different phase delay of 2.9 h and phase advance of 1.6 h. In turn, CrebA knockout flies delayed their phase by 2.6 h and advanced by 1.4 h, while their parental controls exhibited a slightly weaker but not significantly different phase delay of 2.1 h and phase advance of 1.1 h. The same applied for CrebB CrebA double knockout flies, which demonstrated a slightly stronger but not significantly different phase shift compared to their controls. There was also no significant difference in the magnitude of phase delays or advances between knockout flies and controls when the phase was measured on the second to fifth day of DD (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Phase delays and phase advances of indicated genotypes after a brief light pulse either at ZT15 or at ZT21, compared to non-pulsed (NP) controls, visualized using estimation statistics. Top: swarm plots of all individual phases measured on the first day of DD; bottom: distribution of bootstrapped-resampled mean phase differences between non-pulsed and light-pulsed control (left) and experimental (middle) flies (primary deltas); right: distribution of the mean difference between the primary deltas (delta-delta), revealing no phase shift differences between control and experimental flies after light pulses at ZT15 and ZT21. In the effect size half-violin plot, black dot indicates mean of the distribution, and black vertical bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. 5000 bootstrap samples were taken; confidence intervals are bias-corrected and accelerated. p values report results of two-sided permutation t-test. CrebB: For ZT15, the unpaired mean differences are −2.92 h between ZT15 control and NP control (p = 0.0) and −2.82 h between ZT15 knockout and NP knockout (p = 0.0). The delta-delta between control and knockout is 0.10 h (p = 0.909). For ZT21, the unpaired mean differences are 1.64 h between ZT21 control and NP control (p = 0.0) and 1.61 h between ZT21 knockout and NP knockout (p = 0.0002). The delta-delta between control and knockout is −0.03 h (p = 0.966). CrebA: For ZT15, the unpaired mean differences are −2.08 h between ZT15 control and NP control (p = 0.0) and −2.58 h between ZT15 knockout and NP knockout (p = 0.0). The delta-delta between control and knockout is −0.50 h (p = 0.489). For ZT21, the unpaired mean differences are 1.10 h between ZT21 control and NP control (p = 0.0002) and 1.44 h between ZT21 knockout and NP knockout (p = 0.0). The delta-delta between control and knockout is 0.34 h (p = 0.439). CrebB-CrebA: For ZT15, the unpaired mean differences are −2.50 h between ZT15 control and NP control (p = 0.0) and −2.89 h between ZT15 knockout and NP knockout (p = 0.0). The delta-delta between control and knockout is −0.39 h (p = 0.598). For ZT21, the unpaired mean differences are 1.29 h between ZT21 control and NP control (p = 0.0) and 1.50 h between ZT21 knockout and NP knockout (p = 0.0002). The delta-delta between control and knockout is 0.21 h (p = 0.696).

As a second approach to determine the role of Creb in light-dependent synchronization, we examined the kinetics of re-entrainment to a phase-shifted LD. For this, behavior of CrebB and CrebA knockdown flies was recorded during an initial LD cycle for three days and for six days during a second LD, which was phase-delayed by five hours by extension of the last dark phase. Actograms and histograms showing the average locomotor activity both during the first LD and during the last three days of the second LD are shown in Fig. 5. There was no difference in the ability to re-entrain between tim-Gal4>CrebB and tim-Gal4>CrebA knockdown flies and their corresponding controls. The histograms show that control as well as knockdown flies were readily entrained to the new LD schedule by the end of the experiment with a narrow evening peak. The actograms reveal that this behavior was already established on the second day of the new LD regime. Interestingly, the early morning peak phenotype described earlier also persisted through this phase shift.

Double-plotted actograms and histograms showing average locomotor activity of indicated genotypes. Behavior was recorded for three days in an initial 12 h: 12 h LD cycle, six days in a second 12 h: 12 h LD cycle, phase shifted by five hours, and six days in DD at 25 °C. Left histograms show activity during the three days of the first LD phase and right histograms show activity during the last three days of the second LD phase. White area in actograms / white bars in histograms = lights on, gray area in actograms / gray bars in histograms = lights off.

Whereas in mammals the SCN receives light input exclusively through the retina44 the Drosophila central clock is in addition to light input through the visual system also intrinsically photosensitive by expression of the blue light photoreceptor cryptochrome (cry)45,46. Thus, in order to investigate if Drosophila Creb might also relay light information from external photoreceptors to the central clock, we tested the re-entrainment ability of CrebB and CrebA knockdown flies in the same LD shift assay but in a cry01 mutant background. While in the absence of functional CRY adaption to the new light schedule was slightly slowed47, additional loss of CrebB or CrebA did not impair synchronization to the shifted LD (Fig. 5).

Discussion

We report here the unexpected finding that Creb activity seems generally suspensible for normal clock function in Drosophila. Our main results are that (1) loss of CrebB and/or CrebA specifically in all clock cells did not affect rhythmicity and period length in DD, (2) did not alter rhythmic period expression, and (3) did not impair synchronization to light, i.e., phase shifts in response to a light pulse and re-entrainment in a LD shift assay. The only mild, but consistent Creb-dependent phenotype we observed was a slightly advanced morning peak.

The outcome of our DD experiments contradicts earlier reports of increased arrhythmicity and either period shortening or lengthening in CrebBS162 mutants or CrebA knockdown flies, respectively15,20. For CrebB, the discrepancies could be related to the different genetic manipulations applied. While we made use of a clock cell specific gene knockout42, a mutant allele like CrebBS162 affects the whole organism and is more likely to cause developmental and pleiotropic defects. CrebBS162 introduces a stop codon into the CrebB coding sequence just upstream of the C-terminal basic region-leucine zipper (bZip) motif48. CrebBS162 is formally not a null mutation, because it encodes at least two truncated CrebB fragments that can be detected on Western blots, and which most likely are subject to normal phosphorylation20,49. It is therefore possible that the truncated CrebB forms lacking the bZip domain fulfill dominant negative or even antimorphic functions so that CrebBS162 mutant effects may differ from those of a gene knockout.

For CrebA it is less intuitive why results differ between our study and Palacios-Muñoz and Ewer15. In addition to our newly generated CrebA CRISPR knockout construct, and application of two additional CrebA-RNAi lines, the same CrebA RNAi line (BL31900) was used in both studies. Moreover, our results are consistent with a previous study, in which CrebA was identified as a target of Atx2 in mediating the toxicity of Huntingtin50. In this study, CrebA knockdown using line BL31900 in PDF neurons by itself did not affect rhythmicity or period length, and the same was true for CrebA overexpression50. Thus, reasons why we could not replicate the results are more likely to be attributed to slight differences in experimental procedures. For instance, unlike Palacios-Muñoz and Ewer15 we did not include a UAS-dicer construct, which can increase RNAi efficiency, at least in some cases51. Moreover, flies subjected to locomotor activity measurements were a little older in the study of Palacios-Muñoz and Ewer15 (aged up to six days, monitored for up to 10 days in LD and up to 10 days in DD) than in our study. It is known that although cycling of clock proteins within the central clock is sustained, behavioral rhythms lengthen and weaken in aged flies52. Finally, while we (and presumably also Xu et al.50) performed locomotor activity assays at 25 °C, Palacios-Muñoz and Ewer15 conducted their experiments at 20 °C, raising the possibility that CrebA influences temperature compensation. To address these issues, we did perform one experiment at 20 °C, with and without addition of UAS-dicer. Without UAS-dicer, there was no significant effect on period length or rhythmicity when driving CrebA-RNAi with Pdf- or tim-Gal4 (Tab S1). However, adding UAS-dicer resulted in a mild, non-significant period-lengthening with Pdf-Gal4, and a substantial (2.6 h) lengthening with tim-Gal4, but no reduction in overall rhythmicity as reported by Palacios-Muñoz and Ewer15 with tim-Gal4 (Tab S1). While these results may indicate a role for CrebA in regulating period length, the lack of a clear effect after knockdown in PDF neurons makes this rather unlikely, because a subset of these neurons, the s-LNvs, determines the period length in DD53. Also, no other CrebA-RNAi or knockout line resulted in a significant period-lengthening, except for CrebA-RNAi line 1, which resulted in mild period-shortening, when expressed with the Clk856-Gal4 driver (Tab S1). Ultimately, independent CrebA-RNAi lines need to be tested in the presence of UAS-dicer to see if the period-lengthening obtained with tim-Gal4 is indeed due to knockdown of CrebA in clock cells. While we could only partially replicate locomotor defects of CrebA knockdown flies, we did not investigate its role in regulating eclosion rhythms15. Moreover, expression data presented by Mizrak et al.26 was collected in larval brains. Thus, it seems possible that Creb function varies among different developmental stages.

We tested the effect of CrebB and CrebA knockout on the oscillation of two period-luciferase reporters in vivo, as the CrebBS162 mutation was reported to severely affect their expression20. Moreover, it is known that mammalian CREB regulates mPer1 expression. Although surprisingly we could not confirm altered period expression in the CrebB knockout flies, we find that this result is in accordance with the free-running locomotor behavior we observed. Together our experiments clearly suggest that Creb function is not needed for the core molecular feedback loop. This finding is supported by a study of Hendricks et al.48, in which they analyzed changes in rest of flies expressing a blocking or an activating CrebB transgene and verified that observed changes were not caused by altered clock function. In fact, they showed that induction of the transgene did not cause phase shifts in locomotor activity nor affected expression of the clock genes per and tim. So, it appears that contrary to what is known from mammals, Drosophila per is not a direct target of the Creb pathway. In accordance with that, the effects of altered neuronal excitability in the study of Mizrak et al.26 had only weak effects on per mRNA levels. Their results rather suggest that gene regulation sensitive to neuronal activity is mediated through the transcriptional activators of the molecular feedback loop, as differences in transcription were maintained in per0 but not cyc0 mutants. Likewise, the CREB binding protein (CBP) also interacts with the CLOCK/CYCLE heterodimer31,32. The relevance of the CRE sequences within the promotor region of period could be restricted to its role in long term memory, which is distinct from its function in the circadian clock and where per is indeed downstream of CrebB and CrebA54,55,56.

In the DN1p clock neurons tim was identified as a specific target of PKA in response to PDF signaling17. In addition, CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 1 (CRTC1) interacts with CREB to regulate transcription of mPer157 and salt inducible kinase 1, which provides negative feedback and limits phase shifting58. However, in Drosophila CRTC was shown to regulate light-independent tim transcription59. We did not test if loss of CrebB or CrebA affects tim expression, because we assumed this is unlikely the case in the face of normal per oscillations and locomotor behavior.

A crucial difference between the circadian system of mammals and Drosophila lies in the fact that subsets of clock neurons in Drosophila are intrinsically photosensitive by expression of CRY, creating a redundancy between light-input pathways. For this reason, we included CrebB and CrebA knockdown in a cry01 mutant background to study re-entrainment capacity (Fig. 5). However, in both cry+ and cry01 background loss of CrebB or CrebA did not impair re-entrainment. Likewise, phase shifting in response to a light pulse was found not to depend on Creb function within clock cells. This speaks against the suggestion that Creb could constitute a molecular gate for conveying entrainment stimuli to the circadian clock as previously hypothesized25,26. Nevertheless, we find that our results do not contradict these earlier studies, as they show a correlation between effects on Creb and clock gene expression levels, which does not necessarily indicate a causal relationship. Also, the question remains, how Creb levels are upregulated in response to neuronal activity. Together our results hint to the idea that Creb might mainly be an output of the circadian clock. Interestingly, both PKA and CBP also have been reported to affect circadian output, as they were shown to affect free-running locomotor behavior without disturbing clock gene oscillations60,61.

Mizrak et al.26 proposed that Creb does not completely turn on and off clock genes in response to neuronal activity but helps to fine-tune clock gene transcription. This idea is consistent with our findings showing that CrebA and CrebB mutants show only very mild behavioral phenotypes (advanced morning peak in LD, Figs. 1, 5). Moreover, electrical silencing of pacemaker neurons for only a short period does not stop PER oscillations62. The limited effects could also indicate that taking out one component of the pathway is not sufficient to severely disrupt the machinery. For example, while loss of CaMKII alone did not alter free-running behavior13, it did when combined with altered calcium concentrations14. We aimed to rule out possible redundancy or compensatory effects between the two Creb proteins by double knockout/-down but did not observe any strengthening of the existing or emergence of new phenotypes. CrebB and CrebA belong to the protein family of basic leucine zipper proteins which are known to dimerize with each other. Two other members of this protein family, Vri and Pdp1, are important for the circadian clock by forming a second feedback loop to sustain rhythmic Clk expression63. Therefore, it also seems possible that Creb could interact with one of these transcription factors, but further investigation into this direction would be needed. In our experiments we interfered with CrebA and CrebB expression from the moment the respective Gal4 drivers become active during development, which at least for tim expressing cells happens already during early larval stages64. It is therefore possible that compensatory mechanisms take over the regulation of Vri and Pdp1 and thereby resulting in almost normal clock function. We did perform one experiment restricting CrebB knock down to the adult stage only, but this did also not alter circadian behavior in these flies (tim-Gal4; tub-Gal80ts>CrebB-KO (29 °C): n = 11, 100% rhythmic, 24.3 ± 0.5 h), speaking against such compensatory mechanisms.

To conclude, despite all the existing evidence in the field that made Creb a promising candidate to be an integral component of the circadian clock by regulating expression of clock genes in response to neuronal activity changes, we could not confirm this hypothesis. We hope that our surprising results may open up new perspectives and encourage further studies both on the role of the Creb pathway and on identifying a link between neuronal activity and transcriptional regulation within the circadian system of Drosophila.

Responses