Reducing environmental burden of electroplating wastewater treatment by ternary cooperation of zero-valence iron, manganese, and graphitic biochar

Introduction

The rapid expansion of industries, including electroplating facilities, mining operations, tanneries, and paper industries, has generated over 6 × 1011 m3 of wastewater annually1,2,3, representing a pressing issue for human health through soil contamination and the food chain4,5. The electroplating industry is one of the most highly polluting industries, producing wastewater laden with various toxic metals, including Cr, Zn, Cu, and Ni6, and its annual production amounts to 4 billion tons in China7. Treating electroplating wastewater typically requires a high chemical input6 and the generation of hazardous waste8, significantly contributing to global carbon emissions1,3 and aggravating global warming.

The conventional process for electroplating wastewater treatment relies on the consumption of Fe-containing chemicals for the reduction and coagulation/flocculation9,10. Producing these chemicals often results in substantial carbon emissions based on the high energy and chemical input for iron reduction. The ferrous mineral is a practical selection but shows a low electron density for reduction. Extra chemicals are needed to neutralize the acidity with the generated Fe(III) and the toxic elements, increasing the environmental burden. Zero-valence iron (ZVI) can be a more efficient material with a two times greater electron density, and no further precipitation is required as ZVI can uptake the toxic elements directly11. However, the even higher chemicals/energy input and the low efficiency with the surface passivation restrict its practical application12,13, as electron transfer through the passivation layer was a rate-limiting step13. Toxic metals further aggravate the Fe passivation14 with an inhibited electron transfer11,12, hindering the efficiency of ZVI for electroplating wastewater. Improving the electron-donating efficiency of Fe is critical for wastewater treatment, yet it has not been achieved sustainably and requires high chemicals/energy input for atom doping, surface modification15, or lattice engineering16 with high carbon emissions.

Concerns persist regarding the sustainability of managing the resultant toxic sludge or solids with high Fe content17. Management of toxic sludges entails additional procedures (e.g., incineration or stabilization/solidification18) and exacerbates the environmental burdens through the depletion of natural resources and emission of harmful substances19,20. The high Fe content in the electroplating sludges, usually linked with high acidity, underscores the need for a strict stabilization process21,22. The surface accumulation of toxic elements on the ZVI passivation layer11 and easy transport of Fe particles leads to high mobility and bioavailability of pollutants under environmental disturbances16,23, and consequently, a high environmental burden. Therefore, the stability of the toxic metals with the Fe is another vital concern for overall sustainability during the electroplating wastewater decontamination. Significant innovation in developing sustainable strategies is needed to improve electron efficiency and the stability of toxic metals to mitigate the looming threat of climate change.

Biochar technology, a technically proven solution for realizing negative emissions24, could greatly change the current Fe-based approaches for the sustainable decontamination of electroplating wastewater. Thermal reduction with biochar can support the formation of ZVI particles without extra chemical consumption25, and the carbon-negative nature of biochar can alleviate the life-cycle carbon emissions26. Difficulties remain in stabilizing the ZVI particles on the biochar surface with controlled distribution and particle size. Aggregation and ripening of ZVI can damage its reactivity and efficiency25, and the ease of Fe runoff from the carbon surface can result in a high risk of release during landfill operations. Considering the porosity and stability of biochar, a promising approach is to embed the ZVI particles inside the biochar for their stability, and creating a high-pressure environment instead of consuming chemicals to achieve this process can result in a lower environmental burden. Embedding ZVI particles into the biochar principally blocks its interaction with oxidants and thus inhibits surface passivation. Hydrothermal treatment is an energy-sufficient approach to generate high pressure with lower energy and chemical consumption27, which can be a potential method for the ZVI embedment inside biochar. It is unclear whether ZVI can be embedded in biochar with hydrothermal treatment, how electrons are transferred from embedded ZVI to pollutants, and the stability of the embedded ZVI in environmental matrices.

We hypothesize that the ZVI particles can be intensively embedded and anchored in biochar with hydrothermal pretreatment to achieve the efficient decontamination of electroplating wastewater with limited passivation, high stability, and low environmental burden compared to the current Fe-based technology. To test this hypothesis, we designed a combined hydrothermal-pyrolysis process to produce biochar with Fe and Mn dual sites, and Mn involved in supporting the fixation of toxic elements after reduction by ZVI. The proposed strategy embedded mineral particles into the biochar and covered it with cotton-like graphitic carbon. The as-prepared biochar showed a high decontamination performance in a wide range of electroplating wastewater, related to the limited passivation and high electron efficiency of embedded ZVI. High stability with limited toxic metals leaching was shown on the spent solids due to the physical protection of mineral particles, saving resources for further stabilization. Our findings indicate the broad prospects of biochar solutions with species design for sustainable wastewater treatment.

Results and discussion

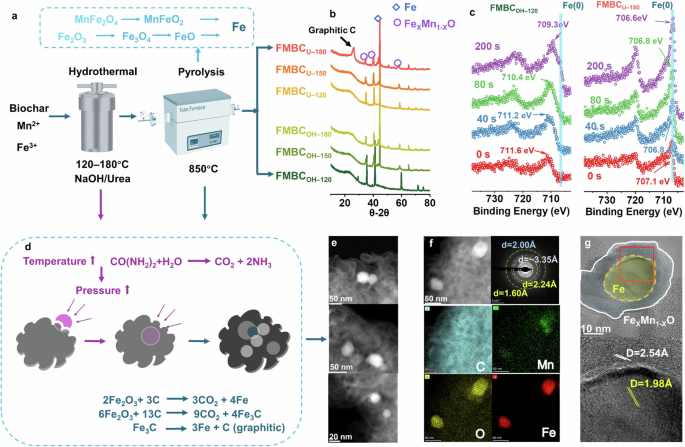

Embedding ZVI inside biochar with carbon and manganese coverage

We conducted a combined hydrothermal and pyrolysis process to manage the Fe/Mn distribution and speciation in the biochar. By changing the hydrothermal temperature from 120 °C to 180 °C and different alkalinity moieties (NaOH or urea), a series of engineered biochars with Fe and Mn was prepared and denoted as FMBCOH–120, FMBCOH–150, FMBCOH–180, FMBCU–120, FMBCU–150, and FMBCU–180 (Fig. 1a). Characteristic peaks of metallic Fe were detected by X-ray Diffraction (XRD) analysis under all conditions except FMBCOH–120, and a sharper peak was found in FMBCU–180 (Fig. 1b). The X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) indicated the existence of Fe(0) on engineered biochar, and Fe(0) became the main speciation after high hydrothermal temperature treatment with urea (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Note 1). The highest amount of Fe(0) was found in the FMBCU–180 compared with other engineered biochars based on XPS deconvolution (Supplementary Note 1). Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) revealed that the nano-sized ZVI (d = 1.98–2.00 Å) formed on the engineered biochar was embedded inside a cotton-like graphitic carbon layer (d = 3.35 Å) with MnO (d = 2.24 Å and 2.54 Å) (Fig. 1d–g). The limited embedding phenomenon occurred under a relatively lower hydrothermal temperature (e.g., FMBCOH–120), and larger particles were commonly found (Supplementary Note 2). High-temperature hydrothermal treatment with high pressure can support ZVI particle embedment, and urea further enhanced this process by self-decomposition under hydrothermal conditions28 with gas generation (Fig. 1d). Notably, the ZVI embedment occupied the pore, especially those with a diameter lower than 10 nm, of the carbon phase, leading to the decreased surface area with lower porosity (Supplementary Note 3). A lower surface area was found for FMBCU–180 compared to that of FMBCOH–120 with limited ZVI embedment, while they can still reach a high value over 361.1 m2 g−1 (Supplementary Note 3)

a Production procedure; b, c ZVI formation on the engineered biochar revealed by XRD and XPS; 0 s, 40 s, 80 s, and 200 s here indicated the etching time before XPS analysis, which is used to evaluate the Fe speciation under different depth of engineered biochar (details in Supplementary Note 1); d Schematic diagram of ZVI formation and embedment during the production process; Distribution of the ZVI within the carbon evaluated by STEM-HAADF (e), STEM-EDX (f), and HR-TEM (g).

Toxic metals removal by the covered ZVI

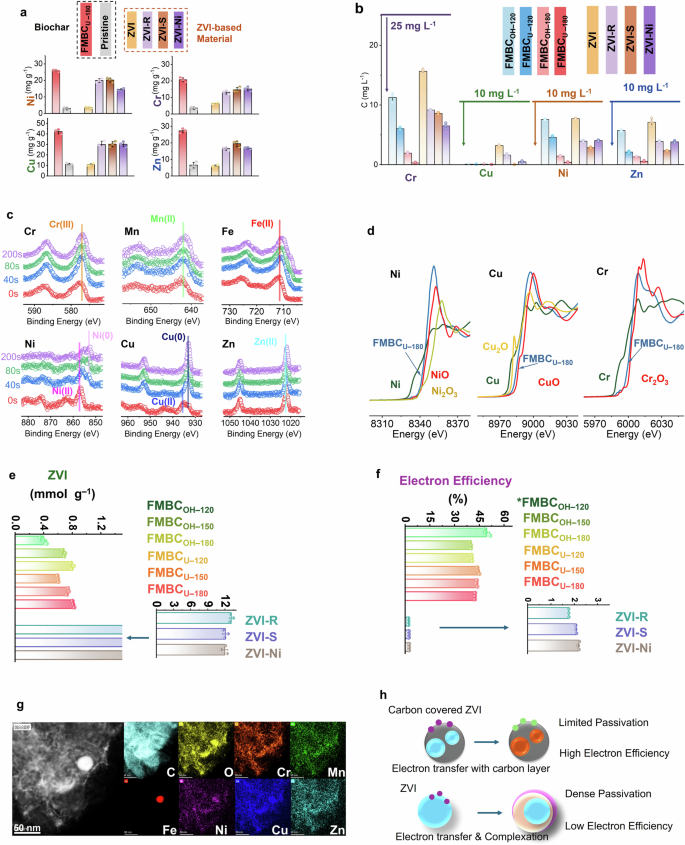

We evaluated the treatment performance of these Fe-Mn biochars for removing toxic metals from electroplating wastewater and compared the performance with ZVI-based materials with the common modification approach, Fe-biochar, Mn-biochar, and pristine biochar. The type and concentration of the toxic metals were selected based on 144 sets of electroplating wastewater reported; that is, nickel (Ni), copper (Cu), chromium (Cr), and Zinc (Zn) with mean values of 36.0 mg L–1, 22.5 mg L–1, 73.0 mg L–1, and 36.4 mg L–1, respectively, and an average pH of 4.5 (Supplementary Note 4).

Fe-Mn biochar performed better than Fe biochar, Mn biochar, and pristine biochar, and the removal performance was up to 2.87, 7.90, 3.20, and 4.91 times higher for Cu, Ni, Zn, and Cr, respectively, implying the importance of both Fe and Mn speciation (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Note 5). By comparing different Fe-Mn biochars, FMBCU–180 showed the highest removal performance for all toxic elements (42.2, 25.8, 27.3, and 20.7 mg g–1 for Cu, Ni, Zn, and Cr, respectively), possibly originating from the ZVI particle embedment process. The removal capacities of FMBCU–180 were 1.40–3.98, 1.27–7.37, 1.40–4.63, and 1.37–3.33 times compared to those of ZVI-based materials for Cu, Ni, Zn, and Cr, respectively (Fig. 2b). In addition, a faster removal was also shown with FMBCU–180 than Fe-based materials, with an over 90% removal for all toxic elements within 4 h (Supplementary Note 5). FMBCU–180 was able to effectively decontaminate the wastewater with mixed metals to meet the emission standards of China29 and the United States Environmental Protection Agency30, while the other materials failed (Fig. 2b). FMBCU–180 performed well across varying pH (2.2–6.3) and anion/cation ratios (0.1–10), indicating its promising application to a broad range of electroplating wastewater (Supplementary Note 5). All these results highlighted the high performance of embedded ZVI for toxic metals removal from electroplating wastewater.

Removal capacities of engineered biochar and ZVI–based materials for electroplating wastewater with sole toxic elements (removed amount, a) or multiple toxic elements (remaining concentration, b); c, d Reduction of the toxic elements indicated by XPS and XANES analysis; e ZVI content in different engineered biochar and ZVI–based materials; f Electron efficiency of ZVI during the decontamination process; * electron efficiency of FMBCOH–120 might be higher than its actual value as parts of the toxic elements was not reduced; g STEM-EDX analysis of the spent engineered biochar; h Schematic diagram of reductive immobilization induced by the carbon-ZVI and uncovered ZVI. The error bar represents the Standard Deviation (SD) from triplicates.

High electron efficiency of covered ZVI for reductive transformation of toxic metals

As indicated by XPS analysis, Cr(VI), Cu(II), and Ni(II) were reduced to Cr(III), Cu(0), and Ni(0), respectively, during the decontamination, while Zn(II) failed to be reduced and remained as Zn(II) (Fig. 2c). X-ray Absorption Near Edge Structure (XANES) analysis unveiled the reduction of Cu, Zn, and Cr by engineered biochar (Fig. 2d & Supplementary Note 6). An almost complete reduction of toxic metals was found with the appearance of FMBCU–180, which might have contributed to its high removal performance, while a considerable number of unreduced species were left in other engineered biochars, as shown by XPS analysis (Supplementary Note 7).

Electrochemical analysis was then conducted to evaluate the redox potential of different engineered biochars, and the highest electron-donating capacity (EDC, 0.79 mmol e– g–1) with a relatively lower oxidation potential was detected for FMBCU–180 compared to other engineered biochars (Supplementary Note 8). The higher ZVI content in FMBCU–180 compared to other Fe-Mn biochars, as quantified by the H2 generation test (0.82 mmol ZVI g–1, Fig. 2e), is crucial for the high reducing capacity, while its accessibility was also dominant25 for the reduction performance. As shown by XPS analysis, FMBCU–180 showed a higher Fe(0) content under the 50 nm depth, and a higher proportion of Fe(0) was detected on the subsurface layer. The high proportion of Fe(0) on the subsurface normally indicate high electron accessibility without the rate-limited electron transfer from core Fe(0) to the subsurface.

With further characterization of the spent engineered biochar, we found that almost all Fe(0) on the engineered biochar was oxidized to Fe(II)/Fe(III) after the decontamination process (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Note 7), suggesting a complete utilization of the electrons on covered ZVI. These electrons might transfer to either pollutants or water/O2 during the immobilization process, and the latter can be considered a waste of electrons16. Thus, we calculated the electron efficiency of ZVI on different materials based on the reduction amount of toxic metals, and a higher efficiency was found for the Fe-Mn biochar (over 39.7%) compared to ZVI-based materials (1.8–2.2%) (Fig. 2f). The low electron efficiency with high electron waste in the ZVI-based materials is responsible for the similar or even lower removal performance with a significantly higher ZVI content (12.0–13.1 mmol ZVI g–1) compared to the FMBCU–180 (0.82 mmol ZVI g–1). In short, covered ZVI in biochar showed a high electron efficiency for the toxic metals reduction and, thus, a higher decontamination performance for the toxic metals.

Contribution of graphitic carbon coverage for efficient electron transfer

Severe passivation by oxidation or complexation processes can result in the low electron efficiency of ZVI-based materials even with surface modification31, which is avoided by the proposed embedment of ZVI inside the carbon structure. Covering with a carbon layer can block the potential interaction between ZVI and O2 during storage, thus leading to a higher remaining Fe(0) content on the surface of Fe particles. The carbon layer might also alleviate the interaction between water or dissolved oxygen with ZVI during the reaction, which wasted the electron for the surface passivation process11. In addition, it can inhibit the direct interaction between ZVI and toxic metals, as evidenced by the analysis of spent FMBCU–180 using STEM-Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (STEM-EDX, Fig. 2g and Supplementary Note 9). All toxic metals were immobilized on the MnO instead of the covered ZVI, unlike the formation of toxic elements-Fe layer (e.g., Cr-Fe complex and As-Fe complex) reported in relevant studies about ZVI-based materials or Fe-biochar11,13. The toxic elements-Fe layer restricts the electron transfer process31, leading to the lower electron efficiency of ZVI.

The graphitization of the outside carbon layer is crucial for the efficient electron transfer process of ZVI inside. A highly graphitic nature of carbon was found on the engineered Fe-Mn biochar, especially for the FMBCU–180. The characteristic peaks of graphitic carbon were shown in the XRD pattern of FMBCU–180 (Fig. 1b), which was missing in other engineered biochars. In addition, the higher G band in the Raman spectroscopy of FMBCU–180 indicated the construction of a graphitic structure (Supplementary Note 10). 2D bands, commonly found in the carbon nanotubes or graphene structure32,33,34,35, appeared in FMBCU–180, further confirming the formation of the graphitic structure. The highest conductivity of the FMBCU–180 implied its highly graphitic nature (Supplementary Note 8) and the electron transfer potential from the ZVI inside to the toxic metals (Fig. 2h). Notably, the formed graphitic layer showed a highly defective nature, as indicated by the sharp D band in Raman spectroscopy, supporting the electron transfer process. The high graphitization degree of the coated carbon is an added value of the embedding process of Fe. Intense Fe-C interaction under high-temperature pyrolysis (>700 °C) with the formation of Fe3C is the key to the formation of graphitic carbon around Fe36,37. Therefore, the embedment of Fe particles inside the biochar supported their interaction and thus facilitated the formation of graphitic carbon for the electron transfer process, leading to the high electron efficiency for the toxic metal reduction process.

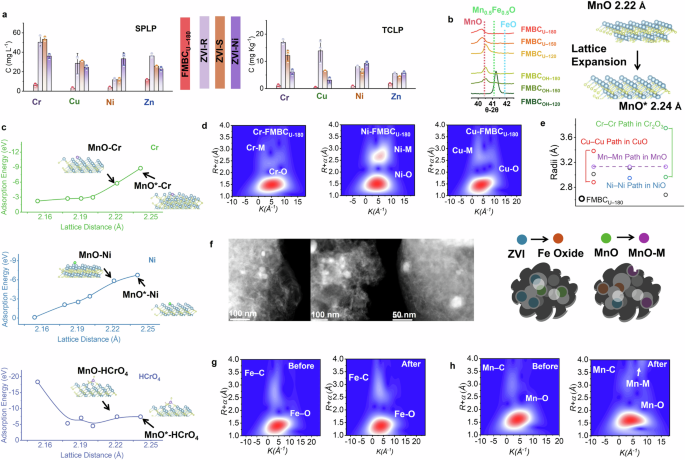

Stability of the toxic metals reduced by covered ZVI

Although the toxic metals were not fixed on the ZVI after reduction, they were removed from the water and showed high stability on the spent engineered biochar, especially by FMBCU–180. Only 6.5 mg L–1 of Cr, 2.9 mg L–1 of Cu, 3.5 mg L–1 of Ni, and 11.7 mg L–1 of Zn could be extracted from FMBCU–180 by the synthetic precipitation leaching procedure (SPLP)38, which was substantially lower than the ZVI-based materials and other engineered biochar. This met the standard as solid waste (non-hazardous) for direct disposal at municipal waste landfills39 (Fig. 3a), indicating no extra stabilization process would be required before the landfill. A similar trend of behavior was observed for the toxicity characteristic leaching procedure (TCLP) methods40 extraction, where toxic metals on the spent engineered biochar showed the highest stability with less release of all toxic metals than the ZVI-based materials (Fig. 3a). High acidity will dissolve the Fe-toxic metals complex with the release of toxic elements during both SPLP and TCLP. In addition, we evaluated the stability of toxic elements under neutral conditions with CaCl2, and a relatively lower released proportion occurred with FMBCU–180 (<0.1%) compared to the ZVI-based materials (Supplementary Note 11). The different fixation patterns and the mineral particle embedment process with carbon might lead to the higher stability of toxic metals on the spent FMBCU–180.

a Released amount of toxic elements from spent engineered biochar and ZVI-based materials by SPLP and TCLP extraction; The error bar represents the SD from triplicate. b Lattice distance of MnxFe1-xO evaluated by the XRD analysis; c Calculated adsorption energy for different toxic metals based on DFT and lattice distance of FeXMn1-XO; d WT-EXAFS analysis of toxic metals on the spent engineered biochar; e Comparison of the metal–metal radii on spent engineered biochar with standard mineral oxide; f STEM-HAADF image of spent engineered biochar with mineral particles chelated inside carbon; WT-EXAFS analysis of Fe K-edge (g) and Mn K-edge (h) of the engineered biochar before and after decontamination.

Lattice engineering of MnO to support the toxic metals fixation

High fixation capacity of the MnO for toxic elements was crucial for the overall decontamination process and their stability. XRD showed that Mn existed as FeXMn1-XO in engineered biochar (Fig. 1b), and the lattice structure changed with the hydrothermal conditions. The high temperature of hydrothermal treatment led to the separation of Fe from FeXMn1-XO, decreased the ratio of Fe in the binary oxide and expanded the lattice to 2.22 Å (pure MnO) with a left-shift of the characteristic peaks (Fig. 3b). Notably, a larger lattice of MnO was found in FMU–180 with a smaller peak position than the standard MnO, representing further lattice expansion of around 0.02 Å. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) revealed the lattice expansion of the MnO with a higher value of 2.24 Å than pure MnO (2.22 Å), and these structures remained after the immobilization process (2.24 Å) (Fig. 3f) and Supplementary Note 9. The lattice expansion might have arisen from the high pressure generated by the high-temperature hydrothermal treatment and the self-decomposition of urea. In addition, atom doping inside the mineral structure, a common approach for lattice engineering41, might occur during the intense embedment of the mineral particles with carbon.

Based on the mineral structure obtained from the XRD and TEM analysis, we evaluated the sorption affinity of various toxic metals on the FeXMn1-XO with different lattice distances and compositions (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Note 12). The continuous lattice expansion resulting from the substitution of Fe by Mn (from 2.15 Å to 2.22 Å) or the lattice engineering (from 2.22 Å to 2.24 Å) promoted the affinity of Cr or Ni atoms on the mineral surface and increased the sorption affinity. Lattice-expanded MnO (MnO*) in FMBCU–180 exhibited the lowest sorption energy for toxic metals, implying its highest fixation capacity and stability (Fig. 3c). In contrast, the lattice expansion decreased the sorption affinity of the HCrO4, suggesting only reduced Cr(III) was sorbed on the Mn surface with greater affinity.

The fixation of toxic metals on the MnO was further verified by the Wavelet Transform (WT)-Extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analysis of the toxic metals (Fig. 3d). The radii of Metal–Metal paths were 3.01 Å, 3.11 Å, and 2.68 Å, for Cu, Ni, and Cr, respectively (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Note 6). Compared with the typical radii of Metal–Metal paths in pure oxides (2.88 Å and 3.38 Å for Cu, 2.94 Å for Ni, and 2.97 and 3.75 Å for Cr), the paths in FMU–180 were approaching the Mn–Mn path (3.13 Å in MnO, Fig. 3e), indicating the potential complexation of toxic metals on the MnO with the formation of a Mn–Cu/Cr/Ni path. Notably, a lower radius of the Cr–M path (2.68 Å) was found even compared to either the Cr–Cr (2.97 and 3.75 Å) or Mn–Mn paths (3.13 Å) in the oxides but similar to the Cr–Cr (2.48 and 2.87 Å) or Mn–Mn paths (2.34 and 2.64 Å) in the metal foil (Supplementary Note 6), indicating the further reduction of Cr(III) to metallic Cr and fixed in the Mn-Cr complex. This was consistent with the XANES analysis that the valence state of Cr should be between 0 and +3 (Fig. 2d). In addition, a decrease in the coordination number of Mn–O from 5.5 to 3.2 after the immobilization process and a lower coordination number of the Metal–O paths of Cu, Ni, and Zn were found (Supplementary Note 6), implying the complexation of toxic metals on MnO with a decreased crystallinity.

Protection of mineral particles by carbon

Mineral particles remained covered with cotton-like carbon after the wastewater decontamination process (Fig. 3f). The high stability of the embedded structure arises from the chemical bonding (i.e., Metal–O–C bonding), as evidenced by the WT-EXAFS analysis. Paths of Fe–O around 1.88 Å as the first shell and Fe–C around 2.95 Å as the second shell can be detected on FMBCU–180 before the wastewater decontamination process (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Note 6), and a limited variation of the coordination environment occurred afterward. Similarly, the EXAFS revealed the construction of Mn–O and weak Mn–C paths, accompanied by limited Mn–Mn bonding (Fig. 3h). The weak metal–metal bonding of both Fe and Mn suggests the stabilization of small particles with carbon anchoring (Metal–C path) instead of large crystal particles (Metal–Metal path). According to the XPS analysis, a unique peak at ~531.2 eV representing the Metal–O–C complexation42 occurred in FMBCU–180, reaffirming the formation of Metal–O–C complexation (Supplementary Note 13). In addition, rich boundary defects on the engineered biochar, especially in FMBCU–180, can act as anchoring sites for the attached minerals, as indicated by the Raman spectrum (Supplementary Note 10)43. This remaining coverage can protect the mineral particles from dissolution, thus leading to high stability during the SPLP or TCLP extraction and a safe landfill.

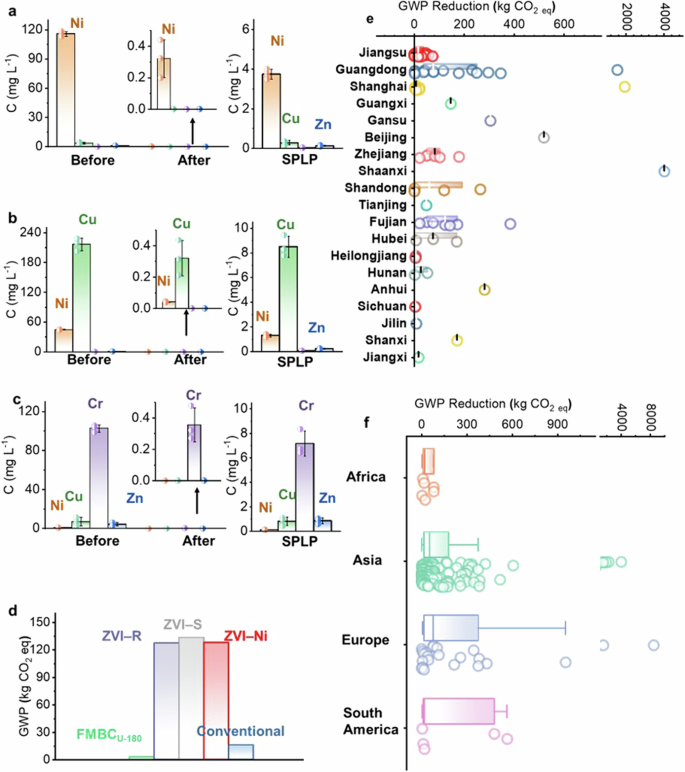

Application potential assessment of FMBCU–180

To confirm the practical application potential of FMBCU–180, samples of three real electroplating wastewater were collected from Fujian and Jiangsu, which had a high toxic metals content (Fig. 4a: 115.8 mg L–1 Ni, Fig. 4b: 216.2 mg L–1 Cu, and Fig. 4c: 102.7 mg L–1 Cr) and complicated compositions. Treatment tests showed that FMBCU–180 effectively decontaminated these real industrial effluents, where the remaining toxic metal concentrations were less than 0.4 mg L–1, and the spent materials could still meet the standard for direct landfill.

Immobilization performance of engineered biochar in real a Ni-dominated, b Cu-dominated, and c Cr-dominated electroplating wastewater; The error bar represents the SD from triplicate. d Comparison of GWP to treat 1000 m3 of electroplating wastewater (25 mg L–1 Cr, 10 mg L–1 Cu, 10 mg L–1 Zn, and 10 mg L–1 Ni) by FMBCU–180, ZVI, or conventional methods; GWP reduction potential by replacing the current technology with FMBCU–180 to treat 1000 m3 of electroplating wastewater in China (e) and around the world (f). In each box plot, the lower and upper bounds of the whiskers denote 10% and 90% quantiles, the center line denotes the median, and the lower and upper bounds of the boxes represent the 25% and 75% quantiles, respectively.

Concerning practical application, the proposed biochar technology should be viable from an environmental standpoint. According to the chemical/energy input for FMBCU–180 production and the generated bio-oil/biogas generation for heat recovery44,45, producing 1000 kg FMBCU–180 would lead to the generation of 0.87 kg CO2 eq (Supplementary Note 14). The proposed FMBCU–180 only consumed 1.91–3.90 kg CO2 eq, for treating 1000-ton of electroplating wastewater with varying properties, which was significantly lower than the conventional approaches with a stabilization process (6.78–38.00 kg CO2 eq, 71.8–89.7% decrease, Fig. 4d). Similarly, replacing conventional technology with FMBCU–180 showed potential benefits for ozone depletion (up to 67.1%), human health (up to 49.1%), land use (up to 91.7%), and water consumption (up to 48.8%) (Supplementary Note 14).

Based on the removal capacities and their environmental footprint, we further compared the environmental burden of the FMBCU–180 with ZVI-based materials. ZVI-based materials exhibited a higher impact on global warming (59.13–138.28 kg CO2 eq), ozone depletion (27.04–62.95 × 10–6 kg CFC11 eq), human health (46.58–107.08 kg 1,4-DCB), water consumption (81.84–328.70 × 10–2 m3), and land use (20.20–46.71 × 10–1 m2a crop eq) for the decontamination of electroplating wastewater (Supplementary Note 14). Using the proposed biochar with ternary cooperation to treat electroplating wastewater only led to 2.3–3.5% of global warming impact, 0.2% of ozone depletion, 0.5–0.9% of human toxicity, 0.8–2.1% of water consumption, and 0.4–0.6% of land use compared to ZVI-based materials. A low Fe/electron efficiency with a high Fe consumption was the main reason for the higher environmental burden, and the utilization of NaBH4, the most common reducing agent for producing nano-sized ZVI-based materials46,47, led to greater emissions (8.68 kg CO2 eq per 1000 kg) than using biomass-containing reducing capacity. The higher stability of toxic metals on spent biochar contributes to a lower environmental footprint with less consumption for stabilization. Notably, recovering the reduction capacity of engineered biochar normally needs a high-temperature pyrolysis process to regenerate ZVI with a high energy consumption. Therefore, benefiting from the high stability of fixed elements and calculated environmental benefits, direct landfill disposal could be a more practical and sustainable choice for the spent engineered biochar.

Implementing the proposed FMBCU–180 and replacing the conventional technology can achieve a high carbon reduction potential for treating electroplating wastewater in China. The common carbon reduction potential is less than 250 kg CO2 per 1000 tons of wastewater, while treating the specific electroplating wastewater collected from Shanghai, Guangdong, and Shaanxi displayed a higher carbon reduction potential (up to 4004.5 kg CO2 eq, Fig. 4e). Considering the annual generation of approximately 4 billion tons of electroplating wastewater in China as an example, implementing biochar technology could achieve a reduction of 0.75 million tons of CO2 eq annually. Given the global prevalence of electroplating wastewater containing highly toxic metals, our technology could lead to a potential carbon reduction worldwide. It was estimated that up to 8472.9 and 4004.5 kg CO2 eq for treating 1000 tons of electroplating wastewater could be achieved in Europe and Asia, respectively (Fig. 4f). The annual global carbon reduction could reach up to 0.27 billion tons of CO2 eq based on the current reported data, and its potential can be further explored when more data is reported in South America and Africa.

Notably, the proposed FMBCU–180 can be applied more broadly (e.g., mining wastewater) to replace the current technology and thereby help to combat global warming. We evidenced that FMBCU–180 can immobilize many pollutants, including As, Tl, Pb, Cd, and organic substances (Supplementary Note 15). Finding the suitable usage of the spent engineered biochar can further enhance its carbon reduction potential if the long-term risk management can be verified and acceptable.

Methods

Production of engineered biochar

The pristine biochar used in this study was produced from locally abundant woody yard waste48 with 2 h pyrolysis at 850 °C (ramping rate as 10 °C min–1). Hydrothermal treatment was conducted in a 100 mL hydrothermal synthesis reactor in which 4 g pristine biochar was mixed with 4 mmol Fe(III), 2 mmol of Mn(II), 8 mmol urea (CO(NH2)2) or NaOH, and 70 mL deionized (DI) water. The hydrothermal reaction was conducted at 120–180 °C for 12 h with a ramping rate as 5 °C min–1. After cooling to room temperature, the resulting suspension was filtered, freeze-dried, and underwent another round of pyrolysis at 850 °C for ZVI formation. The engineered biochars that were prepared were denoted as FMBCOH–120, FMBCOH–150, FMBCOH–180, FMBCU–120, FMBCU–150, and FMBCU–180, based on their hydrothermal conditions and were stored in a sealed container and purged with dry N2 gas before further usage.

Toxic metals decontamination

Batch experiments were conducted to assess the toxic metals immobilization capacity of different mineral-carbon composites in simulated wastewater at 25 °C. Typically, 0.2 g of the engineered biochar was mixed with a 100 mL solution containing different toxic metals. The mixed toxic solution contained Cr (25 mg L–1), Ni (10 mg L–1), Cu (10 mg L–1), and Zn (10 mg L–1) by dissolving the K2CrO4 and corresponding chloride salts. A higher concentration was set for the sole toxic elements system (60 mg L–1 for Cr(VI), Zn, or Ni, and 100 mg L–1 for Cu) based on the decontamination capacities of engineered biochar and the reported concentration in real electroplating wastewater (Supplementary Note 4). The mixture was shaken at 250 rpm at 25 °C, and the solids and solution were separated by filtration after 1-day shaking. The concentration of toxic metals in the solution was evaluated by Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) or Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). The colorimetric method with diphenyl-carbohydrazide31 was used to evaluate the valence transformation of Cr(VI) in the solution phase. The solids were freeze-dried and stored with limited oxygen before further characterization. To evaluate the mobility of the toxic metals on the engineered biochar, SPLP38 and TCLP40 were conducted to evaluate the risk of spent materials as hazardous waste for landfills. ZVI-based materials (Supplementary Note 16) were set as a control to evaluate their performance for toxic metal immobilization.

Mineral/carbon structure analysis

An XPS analysis with etching was used to identify the element speciation under different depths of engineered biochar (Supplementary Note 1). The nanoscale morphology and mineral embedment were analyzed by spherical aberration-corrected (AC) STEM with SAED, High-angle Annular Dark-field imaging (HAADF), and EDX (Supplementary Note 2). X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) analysis was conducted to identify the coordination environment of Fe and Mn in the engineered biochar (Supplementary Note 6). The electrochemical properties, including conductivity and redox capacities, were tested (Supplementary Note 8). XRD was conducted to evaluate the mineral phase regulation on different engineered biochars. Raman spectroscopy identified the carbon properties during the material synthesis (Supplementary Note 10).

Immobilization mechanism

Similar characterization techniques, including XAS (Supplementary Note 6), XPS (Supplementary Note 7), and STEM (Supplementary Note 9), were conducted to analyze the spent engineered biochar to identify the immobilization mechanisms. In addition, the approaching potential of different toxic metals on the mineral surface was simulated by DFT calculations to support the one-step stabilization process (Supplementary Note 12). To evaluate the electron donation efficiency during the reductive immobilization of toxic elements, we calculate the electron efficiency based on the ZVI content and the reduced toxic elements content (Eq. (1)). Based on the XPS analysis, we assumed all removed Cr, Ni, and Cu was reduced first and then immobilized on the engineered biochar. Only a small proportion of Cr(VI), Ni(II), and Cu(II) can be detected on the surface of spent engineered biochar, especially for the engineered biochar produced with higher hydrothermal temperature and urea, and most of them might come from the surface oxidation afterward. Notably, a higher proportion of Ni(II) and Cr(VI) was detected on the FMBCOH–120, which might lead to the exaggerated number of its electron efficiency.

Environmental footprint evaluation

A life cycle assessment was conducted to evaluate the environmental impact associated with the production and application of engineered biochar. The environmental footprint of pristine biochar production was calculated based on the previously reported full-scale facility previously44, considering the gas emission, hauling, alum, stainless steel, electricity consumption, and energy recovery from pyrolysis gas combustion. For the following hydrothermal process and the second pyrolysis, no heat recovery was considered based on the limited pyrolysis gas generation. The environmental footprint for the ZVI-based materials was also calculated based on the production conditions. A comparison between engineered biochar and ZVI-based materials or conventional methods was conducted. All these assessments were based on the removal capacities of toxic elements and the associated consumption of chemicals and energy. Detailed information can be found in Supplementary Note 14.

Responses