Remission of alcohol use disorder following traumatic brain injury with focal orbitofrontal cortex hemorrhage: case report and network mapping

Introduction

Joutsa et al.1 study in Nature Medicine demonstrated that brain lesions disrupting addictive behavior can be mapped to a common brain network. Their analysis included two cohorts of patients with remission of smoking following focal brain damage (primarily stroke). Concurrently, preclinical research is building circuit models for drug-addictive behavior that have identified overlapping hotspots including the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC)2. Here we describe a case of a patient whose alcohol use disorder (AUD) went into remission after a traumatic brain injury (TBI) with focal left OFC intracerebral hemorrhage. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no published reports of focal lesions resulting in remission of isolated AUD (without polysubstance use). Furthermore, we believe that our case complements the recent network mapping study and adds to our understanding of the critical role of the OFC in models of addictive behavior.

In this report, we describe and analyze the case lesion and find that its network map converges on the same topography established in previously described addictive behavior lesion network mapping1, but with an inverse connectivity profile.

Methods

Case

Ms. B is a 42-year-old woman with a chronic history of treatment-refractory AUD, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Previous attempts to reduce alcohol consumption were unsuccessful despite multiple psychosocial (group support and individual counseling) and pharmacological treatment trials (gabapentin, naltrexone). Problematic alcohol use first began in her early 20s following a depressive episode, with further escalation of alcohol use in her 30s in the context of an abusive relationship. Ms. B’s baseline alcohol consumption prior to her presentation consisted of two bottles of wine per day. She denied any other substance use. She lives alone and runs a small business.

One month prior to assessment in the clinic, Ms. B suffered a TBI after falling downstairs while intoxicated by alcohol. She struck her head and lost consciousness with no memory of the incident. Her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 14 on the initial trauma evaluation in the emergency department at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center. She reported headaches, confusion, and dizziness. There was no seizure activity. On examination, she was grossly cognitively intact and had no evidence of focal neurological deficits. Laboratory investigations noted an elevated ethanol level of 86 mg/dL but were otherwise unremarkable.

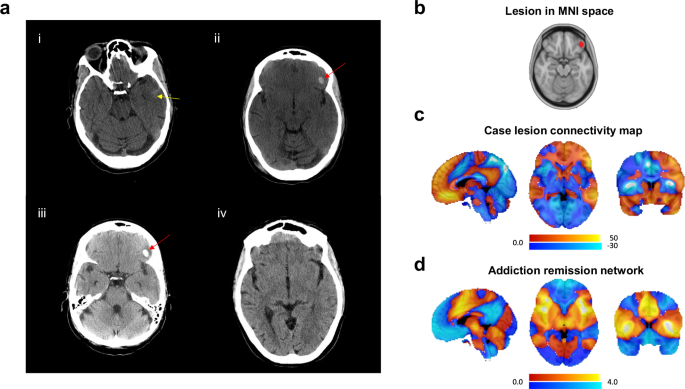

A motion-degraded CT head demonstrated trace subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) along the left anterior temporal lobe with a possible associated thin extra-axial hematoma and small contusion (Fig. 1a). She was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit for neuromonitoring and CIWA protocol. A repeat CT head the next day revealed a new 1 cm, well-circumscribed intracerebral hemorrhagic contusion localizing to the left OFC (Fig. 1a). The previously reported extra-axial hematoma and SAH were less conspicuous. A third CT scan the following day showed only the stable 1 cm OFC hematoma with mild surrounding edema, no other abnormalities were reported (Fig. 1a).

a CT head (axial slices) post-traumatic brain injury: (i) Initial scan in ER revealing trace subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) along the left anterior temporal lobe (yellow arrow) with a possible associated thin extra-axial hematoma and small contusion, (ii) Day 2 scan showing a 1 cm, well-circumscribed left orbitofrontal cortex intracerebral hemorrhage (red arrow), (iii) Day 3 scan showing stable focal hemorrhage (red arrow) with mild surrounding edema, (iv) One-month follow-up scan showing resolution of intracranial hemorrhages and no acute abnormalities. b Lesion location was traced and delineated on the MNI space template brain. c The MNI space lesion was used to compute functional connectivity to all brain voxels. This map was compared to the smoking addictive behavior network described by Joutsa et al. presented in (d). Color scales represent t values.

At assessment in our TBI clinic a few weeks after the injury, Ms. B reported improvement in her symptoms of headache and dizziness but persistent anosmia/ageusia, insomnia, and mild short-term memory difficulties. She denied any focal neurological deficits, and the neurological exam was unremarkable. Interestingly, Ms. B reported a dramatic cessation of her cravings and interest in drinking alcohol after the TBI. This translated to her being abstinent from alcohol for the first time in years. At the time, she continued to take gabapentin prescribed for her alcohol dependence (on a stable dose prior to TBI) and had stopped taking naltrexone two weeks prior to her TBI as she did not perceive any benefit. She has not begun any new medications since the TBI. Shortly after her initial hospitalization, she returned to working full-time and was functionally independent.

Follow-up neuroimaging approximately 1 month after the TBI showed resolution of her focal left OFC hemorrhage. It was reported as normal except for mild cerebellar atrophy believed to be secondary to her chronic alcohol use (Fig. 1a). At 1-year follow-up, she reported one relapse a few months after the TBI that was triggered by increased workplace stressors (in the context of the COVID pandemic). After the relapse, she successfully abstained from alcohol in the four months preceding her 1-year follow-up in our clinic (early remission). She was discharged from the TBI clinic.

Written informed consent for publication of clinical details and/or clinical images was obtained from the patient. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of this journal. This is a case report, and thus, institutional research ethics approval was not required.

Network mapping

To further analyze how this left OFC hemorrhagic TBI lesion could have potentially contributed to remission of treatment-refractory AUD, we collaborated with Joutsa and colleagues to identify the brain circuits affected by the lesion.

The lesion was traced and delineated in a Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space template brain (Fig. 1b). Functional connectivity from the lesion location to all brain voxels was computed using an external connectome created from resting state functional connectivity imaging data from 1000 healthy volunteers, as in the original study1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Network mapping

The case lesion was strongly functionally connected to the ventral prefrontal and temporal cortices (positive connectivity) and the insula and operculum (negative connectivity), but the direction of connectivity to these regions was the opposite compared to Joutsa and colleagues’ smoking addictive behavior remission map (spatial correlation r = −0.59) (Fig. 1c, d).

To test if this correlation was more negative than what would be expected by chance, the spatial correlation coefficient was compared to null distribution created by 10,000 iterations randomly permuting group labels, recomputing the smoking addictive behavior remission map, and then recomputing the spatial correlation with our case1. This analysis showed that the spatial correlation between the case and addictive behavior remission maps was significantly lower than what would be expected by chance (permutation test 1-sided, p = 0.04). In addition, to test if the spatial correlation was lower than that with random stroke lesion connectivity maps, the spatial correlation was compared to that of 200 random stroke cases using Wilcoxon signed rank test, showing that the correlation was lower than that of the random stroke cases (1-sided, z = 12.21, p < 0.001).

Discussion

TBI results from a force transmitted to the head that causes neuropathologic damage and/or dysfunction. Unlike stroke that typically results in discrete region(s) of infarction and is often considered a gold standard for lesion data, TBI can be more complicated to interpret as it can result in diffuse and/or focal damage with heterogenous pathology3.

Joutsa and colleagues used lesion network mapping to identify a connectivity profile mediating remission from smoking addictive behavior1. They also showed that lesions associated with reduced alcoholism risk had a similar connectivity profile suggesting that the findings may generalize to other substance use disorders1. The present case demonstrates that a TBI hemorrhagic lesion resulting in early remission of AUD converges on the same network topography but with an inverse connectivity profile (i.e. positive connectivity to the negative nodes and negative connectivity to the positive nodes of the addictive behavior remission network). Given this finding, it is possible that just disrupting the network, regardless of the direction of the effect, would be sufficient to facilitate addictive behavior remission. This hypothesis would be in keeping with recent work demonstrating that targeting the same symptoms with mechanisms increasing focal brain activity, such as high-frequency repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS), and decreasing focal brain activity, such as a lesion or low-frequency rTMS, converge on the common network but with opposing connectivity profiles4, and effects of DBS that clinically represent therapeutic lesions but are associated with increased blood flow and glucose metabolism at the stimulation site5. Alternatively, if the case lesion was potentially excitatory (rather than a traditional lesion exerting inhibitory effects), then the connectivity profile would align closely with the addictive behavior remission map. Though hemorrhages can induce hyper-excitable brain states (e.g., seizures), we have no supportive data in the present case to corroborate this possibility and this remains speculative.

The OFC is located along the ventral aspect of the prefrontal cortex and is a primary node in executive function networks with strong connections to the medial prefrontal cortex, dorsal striatum, amygdala, and brainstem6. Integrating sensory information and reward-related stimuli for the purpose of evaluating choices is a particularly critical role of the OFC6. Accordingly, the OFC has been implicated in the pathophysiology of addictive behavior/AUD, including the regulation of urges, compulsions, and reward decision-making processes6. Addictive drugs initially target the mesolimbic system and evoke strong dopamine transients in the nucleus accumbens; however, in individuals where compulsion emerges, excitatory projections from the OFC to the dorsal striatum become potentiated7 and this affects both the direct and indirect pathways within the basal ganglia8. Based on these findings, depotentiation of excitatory afferents, or as in the case of a focal lesion, a loss of function would be beneficial for addictive behavior remission.

The intersection of TBI and AUD is complex and given that this is a case report, we were unable to control for other variables that could be relevant to our patient’s remission. This may include cognitive factors related to realization that alcohol consumption/intoxication may have contributed to the TBI, physical barriers such as injury preventing ability to acquire and consume alcohol post TBI or, social factors including financial constraints in accessing alcohol9. The latter two variables were not relevant in our case. Other factors, such as less social interaction or reduced exposure to triggers for alcohol use in the context of recovery from TBI, could have been potential contributors to remission. Her persistent anosmia and ageusia post TBI could have also been a factor impacting her reduced alcohol consumption, but she did not directly cite this as playing a role10. The role of psychiatric symptoms, which often intersect with alcohol consumption, potentially influenced this patient’s alcohol use. It is possible that improvement in symptoms of depression and PTSD could have contributed to this patient’s remission. However, this is not known in our case. It is not uncommon that in the immediate period after a moderate-to-severe TBI, patients with a prior history of AUD reduce their alcohol intake; however, alcohol intake can then subsequently increase with time post TBI9. Another limitation is that potential post-TBI diffuse axonal injury (DAI) and microstructural changes may be present and not be directly observable with standard clinical neuroimaging. It is also important to consider that the OFC injury may have interacted with networks involved in affective dysregulation, and indirectly impacted alcohol use through reduced psychiatric symptom burden. Advanced neuroimaging in research settings suggests that DAI may disrupt large-scale connectivity networks including the default mode and salience networks11 relevant to addictive behavior. Given the limitations in quantifying the presence/extent of DAI and/or diffuse functional network changes in clinical practice, we need to consider TBI as a mechanism generating an isolated focal lesion(s) cautiously.

Responses