Remote cooling of spin-ensembles through a spin-mechanical hybrid interface

Introduction

Translating the potential of quantum technology into real-world applications remains a significant challenge due to the inherent limitations of current experimental platforms1,2. One promising avenue is to explore the hybrid system approach, which promises to fully exploit the unique capabilities of different systems3,4,5,6. In particular, high-fidelity entanglement between different systems can be established by exploiting their common coupling to a transducer, thereby generating indirect interactions6,7. Transducers in the forms of nanomechanical oscillators (NMOs)8,9, magnons10,11, superconducting qubits12,13, superconducting resonators14, optical cavities15, and optomechanical cavities16 have been considered to mediate spin-spin, spin-photon, and photon-phonon interactions.

However, it has been mainly proposed to use transducers to implement entanglement gates between remote qubits9,10,16, and few transducer protocols focus on heat extraction from quantum systems to achieve ground-state cooling or state preparation. State preparation is the foundational step in most quantum applications17,18, making the development of efficient methods essential for advancing areas such as computing, simulation, and sensing. This is particularly critical for spin ensembles, as conventional techniques often rely on resonant energy exchange methods, such as the Hartman–Hahn transfer19,20. Polarization based on energy transfer typically exploits the interaction between a single spin and all the spins of the ensemble. This single spin can be polarized repeatedly, thus realizing a continuous removal of entropy until the ensemble is finally polarized. The challenge is that if the ensemble spins have similar g-factors, the risk of them being trapped in dark states due to Hamiltonian symmetries is high, preventing complete polarization of the ensemble20,21.

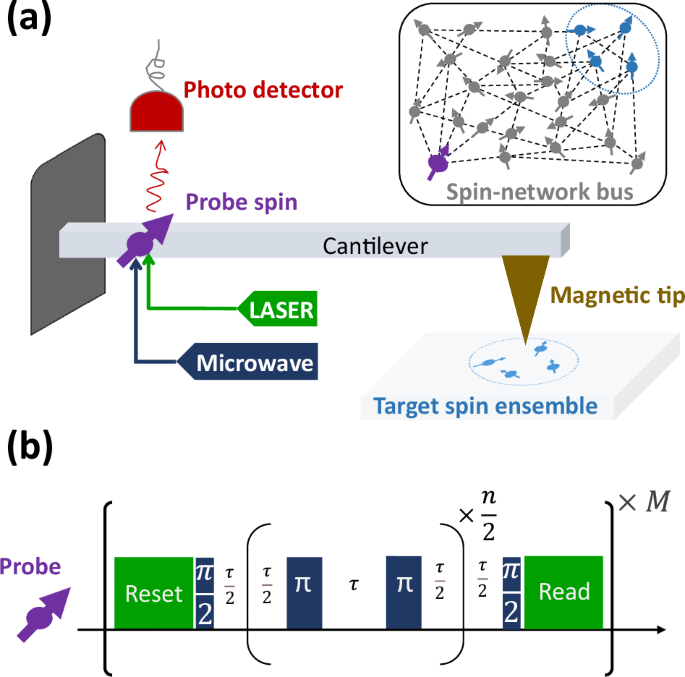

In this work, we consider a tripartite hybrid system where an oscillator serves as a transducer for a single-probe spin and a spin ensemble. By exploiting the measurement feedback from the frequently measured probe spin, efficient heat extraction from the ensemble can be realized, requiring only weak dispersive (off-resonant) coupling between the spins and the oscillator. The probe control sequence is shown schematically in Fig. 1b. Achieving complete ensemble polarization by such probe projections can avoid the dark state problem associated with resonant energy transfer. Furthermore, the ability to operate under dispersive interaction is important for various systems whose original dynamics do not allow direct energy exchange22,23. Finally, we show that the same control sequence on the probe can also be used to prepare macroscopic oscillators (e.g., NMO) into specific quantum states that can potentially be used for sensing and error correction applications.

a Shown is a clamped nano/micromechanical cantilever carrying a single defect spin, which in this study is exemplified by an NV electronic spin. The interaction between the NV center spin and the cantilever motion is mediated by strain, while single qubit gates are achieved by microwave (MW) pulses. Initialization and readout processes are facilitated by optical pulses, with a photon detector used for readout. A magnetic tip at the edge of the cantilever creates a gradient field that allows interaction with a nearby spin ensemble, coupling it to the mechanical motion of the cantilever. In the inset, we schematically represent a network of interacting spins as a quantum bus. When the number of spins in the network is large, it can be modeled as a bosonic system (e.g., magnons) by the Holstein–Primakoff transformation. Note that it is simplified here as the fundamental mode of the cantilever’s vibration. b The control sequence of the probe spin to perform the cooling protocol. First, the probe spin is reset to the (leftvert 0rightrangle) state by optical pulses, then a π/2 MW pulse brings it to a state of equal superposition, which is followed by n inversion MW pulses applied periodically with a carefully chosen time interval τ. To ensure that the effective probe-oscillator coupling strength under pulses is comparable to the oscillator frequency ω, enabling the oscillator to be driven, n should be on the order of ω/g0. Another π/2 MW pulse is applied before the probe is optically read into the computational base. The above process is repeated M times, bringing the oscillator and the spin ensemble progressively closer to their thermal ground states. Note that the probe to be read must be post-selected in (leftvert 0rightrangle) each time, otherwise the whole process starts over.

The oscillator here serves as a simplified conceptual model for a common bus (transducer) connecting two distant quantum systems that are not directly or just weakly coupled. One can consider a general scenario where the bus is a large spin network, which can be effectively approximated as a bosonic system via the Holstein–Primakoff transformation, such as the spin wave excitations (magnons)11,24. This scenario is particularly relevant when a single nitrogen-vacancy (NV) electronic spin in a diamond is used to polarize or probe distant target spins beyond the distance criteria set by the sensing volume25. The target may be distant carbon nuclear spins within the diamond substrate26,27,28, or spins attached to an external protein/molecule29. In such cases, probe-target interactions must be mediated by a transducer, such as the spin network schematically shown in the inset of Fig. 1a10,27,28,29. Despite tuning both the network-to-probe and network-to-target interactions to resonances, the significant inhomogeneities typically present within a spin network make it difficult to become polarized, rendering resonant probe-target energy transfer ineffective27,28,29. Here, we instantiate such a scenario by considering the oscillator as the fundamental mode of an NMO, specifically the vibration of a clamped cantilever, as schematically shown in Fig. 1a22,23.

Results

Tripartite hybrid system

For simplicity, we assume (though not necessary) uniformly, with a coupling strength denoted as g. Note that a discussion on the effects of inhomogeneous coupling can be found in Supplementary Material. In addition, the probe spin is assumed to have a distinct coupling strength with the oscillator, denoted as g0. The hybrid system’s Hamiltonian is then formulated as follows:

where N is the total number of spins in the ensemble; Si,z signifies the z-component of the spin-1/2 operator for the ith spin, oscillating at its Larmor frequency ωi. The oscillator’s annihilation and creation operators are denoted by a and a†, with a frequency ω.

As we will demonstrate later, the assumption of only a single bosonic mode is valid in this work. This validity stems from our manipulation of the probe spin through periodic dynamical decoupling pulses, which effectively couples the probe spin exclusively to the oscillator’s ground-state mode while decoupling it from all others. Moreover, our focus on a small ensemble of only a few spins allows for exact diagonalization of the Hamiltonian system. This approach stands in contrast to typical acousto-magnonic studies, where a bosonic description of much larger spin ensembles is necessary30. Such bosonic approximations are, however, inapplicable in our few-spin limit.

This hybrid system can be realized as shown in Fig. 1a by a unilaterally clamped cantilever, embedding a single NV center positioned at the clamping point such that it experiences maximum strain and thus higher coupling strength. On the free side of the cantilever, we attach a magnetic tip to generate a strong field gradient that couples to a nearby spin ensemble on an external substrate6,9. In this way, we exploit both possibilities to achieve spin-mechanical coupling7,31,32 by local (strain) and non-local (magnetic-tip) coupling of spins to mechanical modes within a single setup. This allows the distinct manipulation of quantum systems that are otherwise not controllable. More details about this possible experimental setup can be found in Supplementary Material.

The NV-cantilever setup we’ve outlined serves as a concrete example of the broader, abstract challenge of harnessing noisy environments. We selected this particular system for two primary reasons. First, achieving polarization is a crucial objective in quantum technology applications using solid-state spins such as NV centers, especially in scenarios where resonant energy transfer is improbable18,21,33. Second, and perhaps more significantly, this setup has already been successfully implemented experimentally32,34, providing a solid foundation for further investigation of using noisy environments as resources.

Original system dynamics

In the following, we will consider the system in the rotating frame with respect to the precession frequencies of both the oscillator and the spins35. The rotating-frame Hamiltonian reads

This Hamiltonian allows us to study the effect of our cooling protocol on each spin configuration with a given eigenvalue of the collective spin operator ({S}^{z}=mathop{sum }nolimits_{k = 1}^{N}{S}_{k,z}), independently. The system evolution operators are then conveniently decomposed into the following form36,37:

where ({mathcal{T}}) the time ordering operator; the terms hk,±(t) are the oscillator Hamiltonians conditioning on the spin states, which are expressed as:

and the operator Ik projects the spin ensemble into the subspace where k spins are pointing up. For example, when N = 3 and k = 2, the projector is written as

It has been shown that the Magnus expansion of the evolution operators can be simplified as36,37

where α(t) = 1 − eiωt and θk is given by

The analysis above can be significantly simplified by considering each spin component with a fixed value of k separately. The initial ensemble state is diagonal in the basis of the collective spin operator Sz, and this diagonal nature is preserved throughout the complete system evolution. Consequently, each k-dependent angle θk becomes a global phase for the corresponding spin component with a particular eigenvalue of Sz, allowing us to disregard it in our analysis. It is also important to note that the oscillator-induced spin–spin interaction, plays no role in the cooling process, as it also takes the form (propto {sum }_{i,j}{S}_{i}^{z}{S}_{j}^{z})38.

Dynamical decoupling pulses on probe

The original system dynamics are unlikely to exhibit energy transfer-like effects due to the weak and off-resonant spin-oscillator couplings. To introduce some tunability into these dynamics, we consider applying a periodic sequence of π pulses to the probe spin. Our cooling method has some similarities to how high-fidelity entangling gates can be realized between an NV electronic spin and a nuclear spin, which is also achieved by periodic dynamical decoupling pulses on the electronic spin39.

Similar to the nuclear-spin polarization schemes35,40, our cooling protocol relies on significantly altering the system dynamics by fine-tuning the spacing between pulses on the probe to match the oscillator frequency. This allows the effects of weak spin-oscillator couplings to accumulate over time, thereby enabling effective cooling of the spin ensemble and the oscillator. These pulses alter the dynamics of the system by replacing g0 with f(t)g0 in Eq. (4), where f(t) a time-periodic function:

with j = 0, 1, 2, ⋯ , n and τ the interval between successive pulses. The conditional evolution operators in Eq. (6) are now written as

where the filter function F(t) is given by36:

This filter function is centered at τ = π/ω with its width decreasing approximately as 1/n236,37,41 and asymptotically converges to a delta function:

This supports our initial assumption in Eq. (1) that all other phonon modes are effectively decoupled from the probe spin when a large number n of pulses is applied. In addition, we also want the maximum possible coupling strength between them. One can see from Eq. (9) that ∣g0F(t)∣ should be comparable to the oscillator frequency ω, which requires at least (napprox {mathcal{O}}(omega /{g}_{0}))37.

The average displacement caused by the ensemble spins can be approximated as αE(k) ≈ g(k − N/2)/2ω, which is notably small compared to the probe-induced displacement. The latter, given by αP ≈ ng0/ω, scales with the number of pulses n when the resonance condition is met, as shown in Eq. (11). Consequently, in a free induction decay experiment of the probe spin, where no dynamical decoupling pulses are applied, the ensemble-induced effects on the oscillator remain undetectable. However, in our protocol, each probe projection modifies the oscillator state, conditioning it on these minute ensemble-induced displacements. Although initially negligible, these effects accumulate over the repeated probe projections, ultimately exerting a significant influence on the system dynamics.

Tuning dynamics through probe projections

In this section, we show how that the dynamics modification is facilitated by a cyclic process involving projective measurement and reinitialization of the probe spin, as schematically shown in Fig. 1a. First, the probe is prepared in the state (leftvert +rightrangle). Then, the system undergoes an evolution for a time t = nτ under repeated dynamical decoupling pulses as described in Eq. (3). Finally, the probe spin is measured in the computational basis after an additional π/2 pulse is applied to it. This process is represented by the circuit in Fig. 2a, which effectively implements oscillator displacement conditioning on the probe spin state.

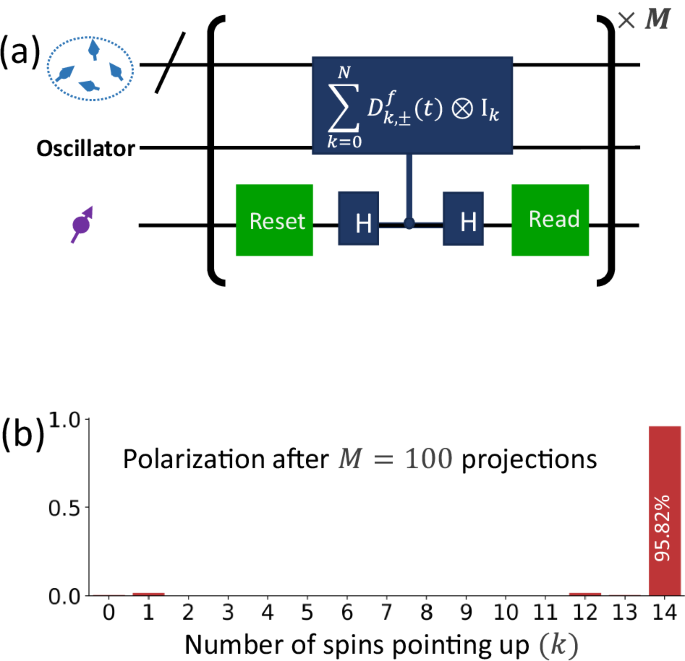

a The quantum circuit progressively projects the oscillator-ensemble system by the projection of the probe spin. The pulse sequence on the physical level is shown in Fig. 1b. In each repetition, the probe spin is first prepared in the equal superposition state (leftvert +rightrangle) by the optical reset and a microwave Hadamard gate. Then repeated dynamical decoupling pulses are applied, resulting in a controlled oscillator displacement ({sum }_{k}{{mathcal{D}}}_{k,pm }^{f}(t)otimes {{rm{I}}}_{k}). Here the subscript ± depends on the spin state of the probe and k on the number of upward-pointing ensemble spins. The procedure ends with a Hadamard gate and a measurement of the probe spin, with the result set to 0. Such a repetition effectively implements the projector given in Eq. (12). b An example of how an ensemble of N = 14 spins is polarized after M = 100 probe projections. The spins are initially in a completely mixed state, which is projected to the state with all spins pointing up with a probability of 95.82%. Note that achieving such a high degree of polarization requires a carefully chosen pulse detuning, which in this case is ϵ = 1.16 kHz. Further simulation details are summarized in Methods.

The whole circuit is equivalent to the implementation of projection operators on the oscillator that depends on the probe spin as well as the ensemble spin states. These conditional oscillator projection operators Vk,± are mathematically formulated as:

where k is the number of ensemble spins pointing up, and the subscript ± depends on the measurement result of the probe spin. Such repeated projections of the probe are central to the oscillator cooling protocol in our previous work37, which is now extended to also cooling/polarizing a spin ensemble.

We start with an ensemble of N spins initially in a fully mixed state and the oscillator initially in its thermal state. These initial states are written as

where projector Ik corresponds to the states with k spins pointing up, as given in Eq. (5); kB represents the Boltzmann constant; and T is the temperature. It is easy to see that (langle mathop{sum }nolimits_{j = 1}^{N}{S}_{z,j}rangle =0); and the initial thermal occupancy of the oscillator is calculated as ({n}_{0}={rm{Tr}}({rho }_{osc},{a}^{dagger }a)=1/left[exp (omega /{k}_{B}T)-1right]).

To cool the ensemble-oscillator subsystem, we repeatedly implement the circuit shown in Fig. 2a by post-selecting the probe measurement outcome to be 0 each time. This process effectively implements the projector ({{mathcal{P}}}_{N,+}) given in Eq. (12) many times. The probability that the ensemble is projected into the Ik sector after M repetitions is calculated as

where m = (2k − N)/2 is the total magnetization of the ensemble. This dependence on m shows that, with appropriate parameters, it is possible to polarize the ensemble, i.e., to obtain PN/2(M) ≈1 when M is large enough.

Furthermore, to achieve tunability of the system dynamics described in Eq. (14) and facilitate our proposed cooling protocol, we introduce the pulse detuning ϵ as a control parameter so that τ = π/(ω − ϵ). We intentionally keep this detuning significantly smaller than the oscillator frequency, so that the dynamical decoupling pulses are in the near-resonance regime. Accordingly, the filter function in Eq. (9) can now be simplified as

In order to make the above equation closer to the delta function given in Eq. (11), a larger pulse number n would be required for higher values of pulse detuning ϵ.

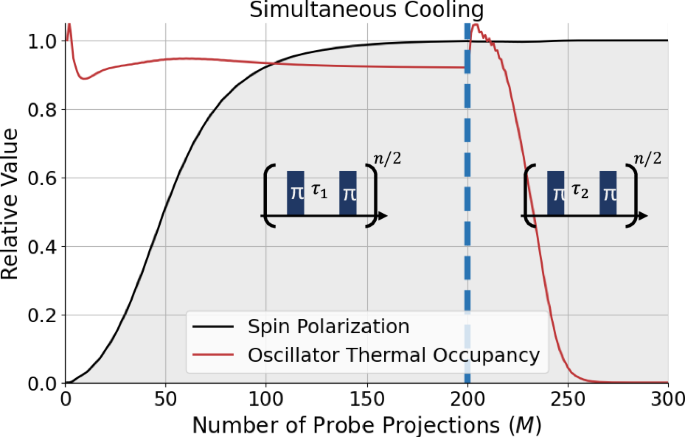

System cooling

In this section, we demonstrate the ability of repeated probe projections to impose a thermal filter on the hybrid system, allowing controlled cooling of either the oscillator, the ensemble, or both. In the case of simultaneous cooling, the oscillator can only be cooled after the ensemble is fully polarized; otherwise, there is effectively no interaction between the probe and the ensemble. As illustrated in Fig. 4, the cooling process for the entire system is divided into two stages with distinct pulse spacings τ. In the first stage, the oscillator remains in its thermal state while the ensemble is cooled. In the second stage, another pulse spacing is used to rapidly cool the oscillator, following the oscillator cooling scheme described in our previous work37.

We explore a range of parameters to identify this effect through numerical simulations, focusing primarily on the weak coupling regime where the coupling strength g is significantly smaller than the mechanical oscillation frequency ω, denoted as g ≪ ω. Details about these simulations are summarized in “Methods”.

To explore this weak coupling regime, we set the spin coupling strengths g, g0 to 10 kHz, while the mechanical oscillation frequency ω is chosen to be 1.2 MHz. Although such a frequency for the mechanical oscillator is experimentally achievable42,43, the chosen values for the spin-mechanical couplings are at the upper end of what is typically achievable in practice37.

These choices represent a compromise between stronger coupling for faster cooling and additional noise due to imperfect pulses on the probe. As we discussed in Eq. (11), at least ({mathcal{O}}(omega /{g}_{0})) pulses are required for each probe projection to ensure that the effective spin-oscillator coupling is comparable to the oscillator frequency, which becomes clear in Eq. (9). However, a higher number of pulses would result in a longer total evolution time to implement the cooling protocol, which is undesirable in the presence of decoherence. Throughout this work, we set the number of pulses in each round of probe projection to n = ω/g0 = 120, ensuring that the effective probe-oscillator coupling strength is sufficiently strong to drive the oscillator, as demonstrated in Eq. (9).

In this work, we refrain from exhaustively exploring all possible parameter regimes. Instead, we focus on fixed coupling strengths and oscillator frequencies that are experimentally feasible, and consider only a few spins in the ensemble. Our primary goal is to demonstrate that manipulating the probe spin, specifically by tuning the pulse detuning amplitude ϵ, can significantly alter the dynamics of a hybrid oscillator-ensemble system with only weak dispersive couplings. The parameter regimes we explore are sufficient to confirm this capability, as we will discuss below.

Pulse detuning as a control parameter

The probability Pm(M) in Eq. (14) depends non-trivially on the filter function in Eq. (15) that is imposed by pulses on the probe. As discussed in our previous work37, varying the value of ϵ can lead to cooling, heating, or squeezing of the oscillator. In particular, ref. 37 has found that a ratio of ϵ/ω ≈5 × 10−3 leads to rapid cooling of the oscillator, which corresponds to ϵ ≈6 kHz for the oscillator frequency of 1.2 MHz.

However, to achieve complete polarization of the ensemble, we must avoid premature cooling of the oscillator before the ensemble is polarized. This is due to the significant effect of the thermal occupancy of the oscillator on the indirect interaction strength between the probe and the ensemble, as elaborated in Eq. (1). In particular, at zero thermal occupancy, the oscillator-mediated effective interaction between the probe and the ensemble spins goes correspondingly to zero.

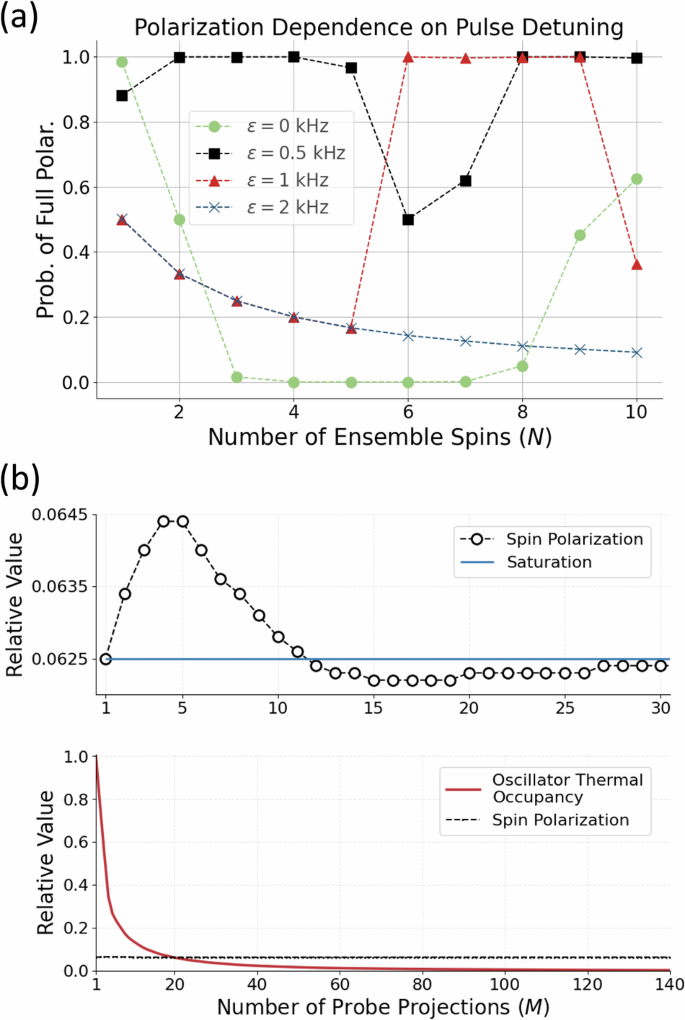

First, we run simulations with the pulse detuning ϵ close to zero to explore the near-resonance regime. By adjusting its magnitude from 0 to 2 kHz and varying the number of spins in the ensemble, our simulations reveal a nuanced relationship between the probability of achieving complete ensemble polarization and the pulse detuning ϵ, as shown in Fig. 3a. To cool the spin ensemble, the choice of ϵ should satisfy the condition that the probe-oscillator coupling is enhanced without prematurely cooling the oscillator. Consequently, satisfying this condition requires fine-tuning of all parameters of the Hamiltonian.

a This panel shows the intricate dependence of achieving complete spin polarization on pulse detuning (ϵ). The probability that all ensemble spins are aligned upward after M = 100 probe projections, denoted by Pm=N/2(M) and derived in Eq. (14), is plotted on the vertical axis. This probability is affected by both the number of spins in the ensemble and the size of ϵ, with ϵ = 2 kHz already appearing too large for effective polarization of the ensemble. b If we choose an even larger detuning (ϵ = 2.5 kHz) and set the number of spins to N = 4, we observe a rapid decrease of the thermal occupancy of the oscillator to zero, indicating that the oscillator is cooling. However, the spin polarization remains almost unchanged and reaches a steady state of 0.0625 after about 40 probe projections. Note that we have considered an ensemble of N = 4 spins, so the y axis represents the relative value of Pz(M)/2. Correspondingly, the y axis also represents the relative value of the thermal occupancy of the oscillator with respect to its initial value, which is set to about 45. Further simulation details are summarized in Appendix 2.

This makes it difficult to determine the exact dependence of the optimal pulse detuning ϵ on the number of ensemble spins N and the number of probe projections M, as shown in Fig. 3a. For example, it can be seen that within an ensemble of constant size, varying the detuning can lead to very different results when implementing the proposed cooling protocol. Another important observation from Fig. 3a suggests that a detuning of ϵ = 2 kHz may be large enough to facilitate rapid oscillator cooling and thereby prevent ensemble polarization.

Premature oscillator cooling

To investigate the premature cooling of the oscillator further, we introduce an even larger detuning of ϵ = 2.5 kHz for an ensemble of N = 4 spins. The simulation results shown in Fig. 3b indicate that at this substantial pulse detuning, the oscillator quickly reaches its ground state after about 80 probe projections. This premature cooling of the oscillator reduces the interaction between the probe and the ensemble, so that the ensemble remains largely unpolarized. The ensemble polarization fluctuates only slightly around the final saturation value for the first few tens of probe projections, as shown in the inset of Fig. 3b.

Furthermore, as an example, we search for the optimal pulse detuning for cooling a larger ensemble of N = 14 spins. An exhaustive parameter search leads us to set the detuning to ϵ = 1.16 kHz. This setting shows that the sector with all spins pointing up (i.e., m = 7) is predominantly left after M = 100 probe projections. The probability of full polarization is as high as 95.82%, as shown in Fig. 2b.

The above results underscore the critical role of ϵ as a controlling parameter in the cooling protocol. In addition, a subtle and interesting aspect of cooling the oscillator is to choose the detuning ϵ precisely so that the conditional oscillator displacement operator is not perfectly aligned with the position or momentum quadrature. Otherwise, the oscillator will be squeezed instead of cooled37. Note that, in the resonant case that ϵ = 0, the displacement operator of the oscillator is along the position quadrature.

This observation is also interestingly related to the encoding of Gottesman–Kitaev–Preskill (GKP) states, which have applications in quantum sensing and quantum error correction44,45,46. Its encoding can be realized by the same control of the probe spin as our cooling protocol. Starting with an oscillator in its zero photon ground state, repeated probe projections can actually increase the number of photons and leave the oscillator in GKP states44,45. The generation of these states in macroscopic objects could enrich our understanding of the quantum-classical interface, notwithstanding their important roles in quantum error correction44,45 and quantum sensing47. More details of GKP encoding can be found in Supplementary Material.

Simultaneous cooling

In this section, we discuss the cooling of both the spin ensemble and the oscillator simultaneously. The key to achieving this goal is to avoid premature cooling of the oscillator, which should instead occur after the ensemble is fully polarized. This requires tuning the pulse detuning ϵ separately for the cooling phases of the oscillator and the ensemble. Figure 4 illustrates a pulse sequence that effectively polarizes an ensemble of N = 4 spins while cooling an oscillator from an initial thermal occupancy of n0 ≈45.

This figure shows the polarization Pz(M) and the thermal occupancy n(ω) for both the spin ensemble and the oscillator, illustrating how the cooling/polarization proceeds with the number of probe projections M. The effective cooling of these quantum systems occurs in different parameter regimes. Initially, the spin ensemble is cooled by adjusting the pulse intervals to near-resonance conditions, specifically τ1 such that ϵ1 = 1.1 kHz. In this case, the thermal occupancy of the oscillator remains largely unaffected. After polarizing the spin ensemble, we change the pulse interval to τ2 with a pulse detuning of ϵ2 = 5 kHz. This more significant detuning leads to a rapid cooling of the oscillator to its ground state. Note that the number of ensemble spins is N = 4 so that the y axis represents the relative value of spin polarization Pz(M)/2. The oscillator thermal occupancy is also plotted as its relative to the initial occupancy n0 ≈45. Further simulation details are summarized in Appendix 2.

During this simulation, we find that the optimal detuning that achieves complete polarization of the ensemble is identified as ϵ1 = 1.1 kHz, while the oscillator occupancy is not much reduced. In this case, performing 200 probe projections can achieve complete polarization of the ensemble. Then, to cool the oscillator, we adjust the detuning to a higher value, ϵ2 = 5 kHz, and execute an additional series of 50 probe projections. This transition in the magnitude of the pulse detuning results in a rapid cooling of the oscillator, as shown in the right part of Fig. 4.

It is important to note that increasing ϵ2 requires a higher number of dynamical decoupling pulses on the probe to achieve a comparable cooling effect, as can be seen from Eq. (15). However, implementing a higher number of dynamical decoupling pulses presents experimental challenges, primarily due to the potential for pulse imperfections. This consideration emphasizes the need for precise control and optimization in the experimental setup.

Discussion

In this study, we have developed a novel ground-state cooling protocol for a tripartite hybrid quantum system consisting of a spin ensemble, an oscillator, and a probe spin. Central to this protocol is the exploitation of the feedback provided by frequent measurements of the probe spin. Our analysis has shown that even with weak dispersive coupling between the spins and the oscillator, one can effectively cool both the ensemble and the oscillator to their ground states, either separately or simultaneously. The proposed cooling protocol offers several desirable features. First, it requires quantum coherence only in the probe, distinguishing it from resonant transfer schemes that demand coherence throughout the hybrid system. In addition, the periodic dynamical decoupling pulses significantly enhance the probe spin’s protection, extending its coherence time well beyond current technological requirements. Furthermore, when applied to a macroscopic oscillator, this polarization technique can be viewed as a remote sensing scheme. This approach allows the sensing volume boundaries to extend beyond the limits imposed by phase accumulation schemes25, offering potential advantages in various sensing applications.

A notable challenge of our cooling approach is its reliance on post-selection, which results in a decreasing success rate as the number of probe projections increases. Nevertheless, our protocol offers a significant advantage for cooling large spin ensembles that are traditionally difficult to handle and cannot be cooled by standard optical or energy transfer techniques. For spin ensembles that are amenable to conventional cooling methods, such as NV centers in diamond, our protocol expands the cooling toolbox by working in conjunction with other methods, thus mitigating the problem of exponentially decreasing success rate. In addition, our analysis of a specific NV-cantilever system suggests the possibility of an exciting experimental demonstration of partial ensemble polarization using currently available technologies.

This research highlights the significant impact that precise control of a single spin can have on the dynamics of a hybrid system, enabling energy transfer-like effects beyond the inherent capabilities of weak dispersive coupling. A similar idea has recently been demonstrated by an intriguing experiment: carefully designed dynamical decoupling sequences on NV electronic spins can enable them to interact with extremely remote nuclear spins through paramagnetic spins (P1 centers)26. In addition to remote sensing, our results also provide valuable insights into the preparation of complex quantum states in a macroscopic object, such as the GKP states.

Methods

Simulation details

The coupling parameters are also g0 = g = 10 kHz, with an oscillator frequency of ω = 1.2 MHz. Accordingly, we set the number of dynamical decoupling pulses for each round of probe projection to n = 120, see the probe control sequence in Fig. 1b. This is to ensure that the effective probe-oscillator coupling is comparable to the oscillator frequency, as discussed in Eq. (11).

In this work, we perform the simulation by calculating the dynamics directly on the initial Hamiltonian given in Eq. (1) without any approximation. In addition, for simplicity, we approximate the oscillator mode as having only 100 levels, which is expected to be sufficient since we assume an initial oscillator thermal occupation of n0 ≈45 in the simulations.

Responses