Retinal blood vessel diameter changes with 60-day head-down bedrest are unaffected by antioxidant nutritional cocktail

Introduction

Deconditioning of the cardio- and cerebrovascular system is one of the significant adverse effects of long-term spaceflight1,2. Fluid shifts and the reduction of circulating blood volumes will lead to macrovascular changes (e.g., changes in blood pressure and abnormal left ventricular stroke volumes)3,4, which can ultimately affect orthostatic tolerance. However, how microgravity-induced deconditioning of the cardiovascular system affects the microcirculation that makes up the bulk of the circulatory system is understudied. These small microcirculatory blood vessels are essential blood pressure regulators and sites for nutrient exchange between the blood and tissues5,6. Long-term space flight has been associated with increased oxidative stress7, which could explain why microvascular endothelial vasodilation is impaired during spaceflight8. Furthermore, microvascular dysfunction in the brain could contribute to induced spaceflight presyncope1.

The retinal blood vessels share functional and structural characteristics with the cerebrovascular microcirculation9. Both the retinal and cerebral microvasculature rely on myogenic mechanisms to adapt to changes in blood pressure. In addition, these blood vessels respond to metabolic and vasoactive neurotransmitters, and local secretion of endothelial vasodilators and vasoconstrictors influences the autoregulatory properties of these vessels10,11. The retinal microvasculature can be visualized directly and non-invasively with a fundus camera. Therefore, analyzing the dimensions of the retinal blood vessels offers a quick, non-invasive, reproducible way to assess (cerebro)vascular function and detect early signs of vascular changes and dysfunction12.

Head-down bedrest (HDBR) affects human physiology in a similar way as long-term spaceflight/weightlessness affects an astronaut’s physiology13,14. During HDBR, a cephalic fluid shift prevents the blood from pooling in the lower extremities and causes a shift toward the upper body15. This fluid shift presents a challenge for retinal and cerebral microvessels, which will have to accompany the increased blood volume. Previous studies have shown that bedrest leads to a decrease in retinal arteriolar diameter, an increase in retinal venular diameter16,17, and a decrease in cerebral blood flow velocity18. In addition to the fluid shifts, real and simulated microgravity leads to an increase in oxidative stress19,20,21, impacting microvascular function. Several studies have experimented with antioxidant cocktails to reduce oxidative stress19. In this study, a combination of polyphenols, vitamin E mixed with selenium, and omega-3 acid was used to support cardiovascular health. Each of these separate components has been shown to improve cardiovascular function and health by reducing oxidative stress, exerting anti-inflammatory effects, and/or improving endothelial function in healthy subjects or patients with cardiovascular disease22,23,24,25,26,27. However, whether these antioxidant cocktails also protect against microgravity-induced microvascular deconditioning remains to be explored.

We assessed the retinal and cerebral microvascular changes in healthy male participants undergoing 60-day term 6-degree HDBR by analyzing retinal vessel widths and measuring cerebrovascular regulation. We hypothesized that retinal and cerebral microvascular changes of the participants receiving the antioxidant/anti-inflammatory cocktail would be attenuated, when compared to the participants in the control group.

Results

Study population characteristics

Of the 20 participants recruited, one participant was not included in our analysis due to non-compliance with data collection rules28. The remaining participants were adult males between 20 and 45 years of age (average 34 ± 9 years). They were between 1.68 m and 1.84 m tall (1.76 ± 0.05 m) and weighed between 65 kg and 85 kg (73.5 ± 6.1 kg). BMI was between 21.9 and 25.4 (23.7 ± 1.5). Baseline characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Retinal blood vessel diameter changes during HDBR

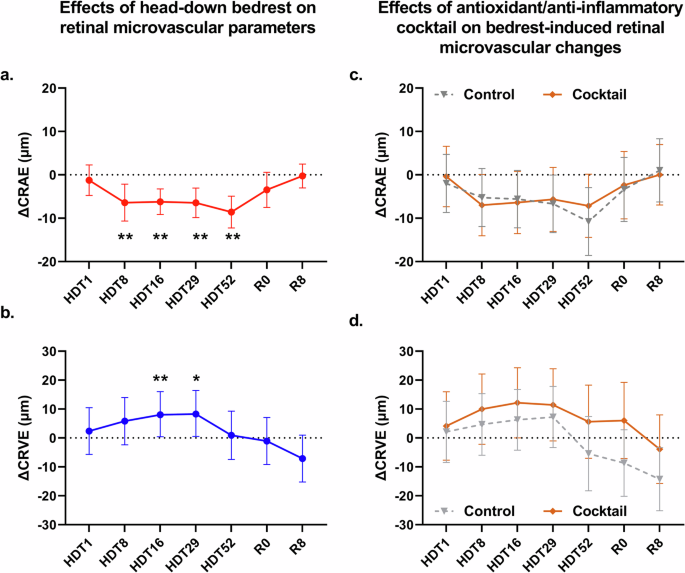

The changes in CRAE (∆CRAE) relative to the baseline values obtained two days before the start of the intervention (BCD-2), are visualized in Fig. 1a. After 8 days of HDT (HDT8), CRAE decreased by 6.40 μm (95% confidence interval [CI]: −10.65 to −2.16; p = 0.0087) when compared to BCD-2. CRAE remained significantly decreased during the remainder of the HDBR campaign (HDT16, HDT29, HDT52). ∆CRAE returned to zero during the recovery period (R0 and R8). The nutritional intervention did not attenuate the effects of head-down bedrest on ∆CRAE (p = 0.098) (Fig. 1c).

a Red circles (with full red line) represent the change in central retinal arteriolar equivalent (ΔCRAE) relative to baseline (BCD-2) during the 60-day study period and during recovery (R0, R8). b Dark blue circles (with full dark blue line) represent the change in central retinal venular equivalent (ΔCRVE) relative to baseline (BCD-2) during the 60-day study period and during recovery (R0, R8). c The effects of HDBR on CRAE (ΔCRAE) of the group receiving the antioxidant/anti-inflammatory cocktail (brown diamonds, full brown line) was not statistically different from the effects of HDBR on ΔCRAE of the control group (gray triangles, dashed gray line). d The effects of HDBR on CRVE (ΔCRVE) of the group receiving the antioxidant/anti-inflammatory cocktail (brown diamonds, full brown line) was not statistically different from the effects of HDBR on ΔCRVE of the control group (gray triangles, dashed gray line). Circles represent the effect estimates from the mixed effect model, error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs BCD-2.

The changes in CRVE (∆CRVE) relative to the baseline values, obtained 2 days before the start of the intervention (BCD-2), are visualized in Fig. 1b. ∆CRVE increased during head-down bedrest, but did not reach statistical significance until HDT16 [8.23 μm (95% CI: 0.44–16.02; p = 0.038) when compared to BCD-2. ∆CRVE returned to zero during the recovery (R0 and R8). Similar to ∆CRAE, the nutritional intervention did not attenuate the effects of head-down bedrest on ∆CRVE (p = 0.198) (Fig. 1d). The average values of CRAE and CRVE during the study can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Cerebrovascular regulation during HDBR

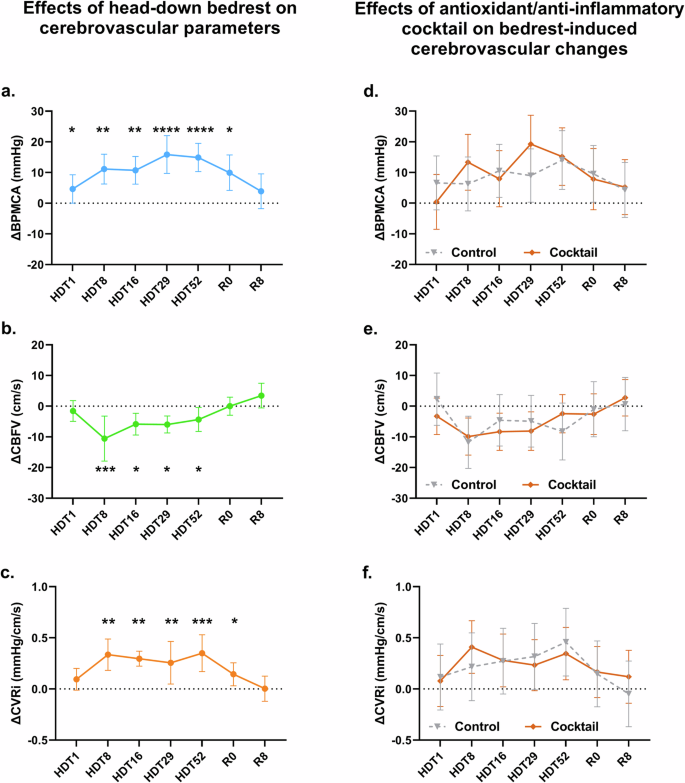

Mean arterial pressure at the level of the MCA (BPMCA) was significantly elevated from HDT08 until R0 compared to BDC-2 (Fig. Fig. 2a). HDBR had a similar effect on the BPMCA of participants in the Control and Intervention group (Fig. 2d).

a HDBR induced an increase in arterial pressure at the level of the middle cerebral artery (BPMCA, light blue circles, light blue line) relative to baseline (BCD-2) during the 60-day study period (ΔBPMCA). b HDBR decreased cerebral blood flow velocity (CBFV, green circles, green line) relative to BCD-2 during the 60-day study period (ΔCBFV). c HDBR induced a decrease in cerebrovascular resistance index (CVRi, orange circles, orange line) relative to BCD-2 during the 60-day study period (ΔCVRi). d The HDBR-induced changes in BPMCA in the antioxidant/anti-inflammatory cocktail group (brown diamonds, full brown line) were statistically not different from the HDBR-induced changes in BPMCA in the control group (gray triangles, dashed gray line). e The HDBR-induced changes in CBFV in the antioxidant/anti-inflammatory cocktail group (brown diamonds, full brown line) were statistically not different from the HDBR-induced changes in CBFV in the control group (gray triangles, dashed gray line). f The HDBR-induced changes in CVRi in the antioxidant/anti-inflammatory cocktail group (brown diamonds, full brown line) were statistically not different from the HDBR-induced changes in CVRi in the control group (gray triangles, dashed gray line). Circles represent the effect estimates from the mixed-effect model, error bars represent the 95% confidence intervals. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001 vs BCD-2.

Cerebral blood flow velocities (CBFV) were reduced during HDBR from HDT08 until the end of the experiment when compared to BCD-2 values (p < 0.0001). CBFV returned to normal at R0 (Fig. 2b). These changes were similar between the Control and Intervention groups (Fig. 2e).

Calculated cerebrovascular resistance (CRVi) was significantly elevated from HDT08 until HDT52 (Fig. 2c). The increase in CRVi during HDBR was comparable between the Control and Intervention groups (Fig. 2f). The average values of the cerebrovascular measurements during the study can be found in Supplementary Table 1.

Retinal blood vessel diameters in association with cerebral vascular measurements

When assessing the associations between the retinal blood vessel diameters and the cerebrovascular parameters, we found significant associations between the changes in CRAE and CBFV (ρ = 0.23; p = 0.035), CRAE and CVRi (ρ = −0.27; p = 0.0008) and CRAE and MCA (ρ = −0.41; p = 0.0002). We did not find any associations between CRVE and any of the cerebrovascular parameters.

Discussion

Long term 6° HDBR has a measurable effect on the retinal microvasculature and cerebral autoregulation. HDBR causes a significant decrease in CRAE while concomitantly increasing CRVE. In the cerebral vasculature, HDBR increased mean arterial blood pressure and cerebral vascular resistance index while reducing cerebral blood flow velocity.

HDBR induces a cephalic fluid shift and increases hydrostatic pressure in the upper body. The CRAE did not change significantly on HDT01 when compared to baseline measurements (BCD-2). The HDT01 measurements may have been collected too early to observe any measurable effects of HDBR-induced fluid shifts. The retinal microvasculature possesses a remarkable capability for autoregulation. In order to maintain a constant blood flow, retinal vessels constrict or dilate depending on increases or decreases in systemic blood pressure. Even though BPMCA was significantly increased on HDT01, when compared to BCD-2, we did not observe a decrease in CRAE at the same time point. The increase in BPMCA may not have been large enough to trigger changes in CRAE (e.g., the myogenic response of the retinal arterioles was counteracted by the increase in hydrostatic pressure induced by the cephalic fluid shift). However, on HDT08, after a week of bedrest, we observed a significant decrease in CRAE. We expected that, at this timepoint, the vascular system would have compensated for the cephalic fluid shifts and that the retinal arteriolar diameter would have returned to baseline levels. However, at the same timepoint (from HDT08 until the end of the experiment), we observed a significant increase in BPMCA. Our BPMCA measurements contrast with other long-term bedrest studies that have shown no change or a decrease in MAP when compared to pre-bedrest levels29,30,31. It is plausible that in our study the participants’ retinal vessels responded to the increased arterial pressure through the myogenic response, resulting in vasoconstriction. The decrease in CRAE persisted until the end of the experiment. A recent study analyzing the effects of physical inactivity (using horizontal bedrest as simulation) on retinal vessels has shown that immobilization alone also causes CRAE to decrease significantly16. During prolonged HDBR, the increased production of vasoactive agents or reactive oxidative species (ROS) may contribute to retinal arteriolar vasoconstriction by limiting the endothelium’s capacity to produce vasodilators such as NO32,33,34. In future studies, monitoring and analyzing vasoactive agents could help to distinguish between local and systemic influences on microvascular changes during HDBR. When the retinal microvasculature experiences prolonged exposure to high blood pressures and/or vasoactive agents during HDBR, it is possible that vascular wall remodeling occurs, which can result in permanent vasoconstriction. During the recovery phase (R0 and R8), the CRAE returned to baseline. At the end of HDBR, a new fluid shift occurs, which could lower the blood pressure in the retinal arterioles. As a result, vasodilation occurred. These dynamic changes showed that the retinal arterioles retained their functionality (capability to vasodilate). This is suggestive of the fact that the observed changes during HDBR were functional rather than structural since CRAE measurements made on R8 were comparable to the baseline levels of BCD-2.

The widening of the CRVE reached statistical significance after sixteen days of HDBR (HDT16). However, CRVE values had returned to baseline levels at the HDT52 measurement. When compared to arterioles, the vessel wall of venules contains less smooth muscle. Therefore, the venules will be stretched when luminal pressure increases, since the myogenic response is unable to overcome the increase in luminal pressure. As a result, venules can act as a reservoir and pool blood. Although not measured directly, retinal blood flow presumably decreases because of the arteriolar narrowing, as shown in the data. Since the changes in CRVE co-align with changes in the retinal arteriolar diameters, it is likely that retinal venular widths are being influenced by blood flow. Similar to the retinal arterioles, retinal venules remained dilated, even after the vascular system had compensated for the cephalic fluid shift. In contrast to the retinal arteriolar vasoconstriction that persisted throughout the HDBR experiment, retinal venule vasodilation only lasted until HDT52. At this timepoint, retinal venular diameters have returned to baseline levels, even though retinal arteriolar diameters remained lower than baseline levels and MCA levels remained elevated. Whether these retinal venular changes were a harbinger of vascular (compensatory) changes or due to other vascular, hydrostatic or metabolic changes remains to be investigated.

Our cerebrovascular measurements indicate that HDBR causes a decrease in cerebral blood flow velocity and that the resistance of the cerebral blood vessels increases. These findings are in agreement with Sun et al. and Ogoh et al. who found that HDBR decreased CBF velocities in 21 days and 60 days of bedrest, respectively18,35. A likely explanation for these observations is that HDBR also causes vasoconstriction in the cerebral (arteriolar) microvasculature. In a recent study, van Dinther et al. found an association between retinal microvascular function and cerebral microcirculation. In this study, retinal arteriolar dilation was associated with pseudo-diffusion of circulating blood in normal-appearing white matter and cortical gray matter36. Other studies have found that retinal vessel density parameters are associated with cerebral small vessel disease37,38. Further supporting this hypothesis are the associations we found between the narrowing CRAE and the decrease in cerebral blood flow velocity and cerebral vascular resistance index. These findings further illustrate the potential use of measuring the retinal blood vessels to gain insight into the microvasculature of the brain.

The use of the anti-inflammatory/antioxidant cocktail could not prevent the changes in retinal vessel diameters or cerebrovascular measurements. We expected that the antioxidants would prevent retinal arteriolar vasoconstriction and venular vasodilation. However, we did not observe any differences in CRAE or CRVE between the Control and Intervention groups during the HDBR experiment. Therefore, we conclude that the anti-inflammatory/antioxidant cocktail is insufficient to prevent the microvascular changes induced by HDBR. The anti-inflammatory/antioxidant cocktail consisted of elements that have been shown to have long-term protective effects on cardiovascular health. However, one must take into account that the (long-term) mechanisms underlying the development of cardiovascular diseases (e.g., inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelium dysfunction) and the (short-term) mechanisms leading to microvascular changes in our study (fluid shifts induced by HDBR and cardiovascular deconditioning) are different. It remains possible that the administration of the anti-inflammatory/antioxidant cocktail reduced oxidative stress and inflammation in the participants, but that these beneficial effects were masked by the severity of the deconditioning that occurred during HDBR. The anti-inflammatory/antioxidant cocktail was also unable to prevent the deterioration of other parameters (e.g., bone turnover and skeletal muscle deconditioning) that were investigated during this study4,39,40.

We are aware that this study has several limitations. Although the study sample size was small, it is comparable to other bedrest campaigns. Even though we only recruited healthy males in order to limit physiological variation, we observed a large variation in cardiovascular reactions due to our participants’ anthropometrics (e.g., age or weight) or other unknown factors. We were unable to collect from female participants since they were excluded from this ESA supported bed rest campaign. The female cardiovascular system responds to alterations in blood pressure via changes in heart rate, rather than changes in peripheral vascular resistance as observed in men41, and the menstrual phase is known to affect cardiovascular responses during different perturbations42. Future studies should strive to include both male and female participants in order to account for these sex differences.

Our fundus images were collected at large time intervals. We might have missed important retinal vascular changes that occurred in the hours following the hydrostatic pressure changes at the beginning and end of the HDBR experiment. More frequent imaging the retina was not possible as the number of measurement times was limited, and many different parameters had to be measured at these time points. Additionally, the single retinal images collected at each time point can only reveal the width of the retinal vessels not whether they are still functioning properly. In a recent study, we showed that retinal vessel imaging and analysis before and after a maximal endurance test can be used to track (functional) changes in the retinal microvasculature43. However, since such a test is impossible to conduct during HDBR, retinal vessel measurements should be paired with methods that can assess microvascular endothelial function such as flow-mediated dilation. Alternatively, flicker stimulation has been shown to induce retinal vasodilation44. However, a flicker stimulation device has not been developed for bedrest protocols, and implementation of such a measurement would be technically challenging. Finally, some astronauts develop spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS), which is characterized by globe flattening, hyperopic refractive error shift, optic nerve sheath distension, optic disc edema, choroidal and retinal folds and focal areas of ischemic retina, symptoms that can be detected on fundus images45. Our study focused on vascular changes, and SANS investigations were beyond our scope and we cannot make any statements about whether or not any of our participants developed SANS and/or how retinal microvascular changes contribute to the development of SANS. In one study, however, the density of the retinal vessel network of astronauts with SANS decreased when compared to astronauts without SANS46. This indicates that retinal vessel analysis may hold important information for the development of SANS, and this hypothesis warrants further investigation.

In conclusion, our study indicates that head-down bedrest has a significant effect on central retinal vessel diameters as assessed by retinal image analysis. Myogenic reactions are the most likely cause for decreases in central retinal arteriolar equivalent, and blood pooling may explain the observed increase in venular equivalent in this study. These microvascular changes in the retina and the brain are reversible after 60 days of HDBR. However, it is still uncertain whether and when long-term (simulated) weightlessness produces irreversible damage. The microvascular health of astronauts taking part in future long-term spaceflight experiments could be monitored using retinal imaging. When combined with other functional assessments, imaging the retinal microvasculature provides insights into microvascular function and may be utilized to anticipate or identify undesired cardiovascular and cerebrovascular consequences linked with spaceflight.

Material and methods

Study participants and ethics statement

The study was carried out by MEDES, the French Institute for Space Medicine and Physiology, Toulouse, France. A total of twenty healthy, non-smoking, active (between 10,000 and 15,000 steps per day) male participants were recruited. None of the participants were taking drugs or medication. All participants gave informed consent to the experimental procedures, which were approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes/CPP Sud-Ouest Outre-Mer I and the Agence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire des Produits de Santé. The study was funded by the European Space Agency (ESA) and conducted at the Space Clinic of the Institute of Space Medicine and Physiology (MEDES) in Toulouse, France.

Study design

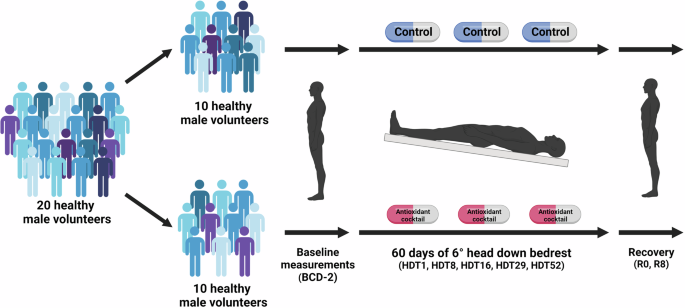

Baseline data measurements were conducted 14 days preceding the 2-month HDBR period. In the 14 days after completion of the HDBR protocol, additional measurements were collected during the recovery period. During the HDBR period, the study participant lay in a supine position with a −6° tilt. During the daily extraction for toilet procedures and weighing (20 min), participants were placed on a gurney with a 6-degree head-down tilt. In addition, participants were discouraged from making any unnecessary limb movements during HDBR. Each participant underwent a daily medical examination during which standardized measurements were collected. The participant’s diet was monitored by MEDES nutritionists, and the Toulouse Hospital provided the meals. The twenty participants were randomly divided into two groups in a double-blinded manner. Half of the participants were assigned to the “Control” group, and the other half were part of the “Intervention” group. The “Intervention” group received a daily antioxidant/anti-inflammatory cocktail in pill form (741 mg of polyphenols, 168 mg of vitamin E mixed with 80 μg selenium, and 2.1 g of omega-3 acid). The “Control” group received a placebo. Pills were given at mealtime to limit the risks of gastrointestinal issues. The HDBR campaigns were conducted in January and September 2017. For each HDBR campaign, five participants were sampled from the “Control” group, and five were sampled from the “Intervention” group (Fig. 3).

Twenty healthy males were randomly and evenly divided into two groups (control and antioxidant/anti-inflammatory cocktail). Both groups underwent 60 days of 6-degrees head down bedrest (HDBR). Retinal and cerebrovascular measurements were taken before (BCD-2), during the HDBR (HDT1, HDT8, HDT16, HDT29, and HDT52) and during the recovery phase (R0, R8). This figure was Created with BioRender.com.

Retinal imaging and analysis

Retinal images were made with the Optomed Smartscope Pro (Optomed Oy (Ltd.), Oulu, Finland). This non-mydriatic handheld camera permitted the acquisition of retinal images while the study subjects were in a (horizontal or head-down) supine position. The fundi of subjects’ right eye was photographed twice at the following specific time points: two days (BDC-2) before the start of the bedrest campaign, on days 1 (HDT01), 8 (HDT08), 16 (HDT16), 29 (HDT29), and 52 (HDT52) of the bedrest campaign, as well as on the first (R0) and eighth day (R8) of recovery. Retinal images were collected in the supine position (horizontal at BCD-2, R0, and R8; head down at HDT01, HDT8, HDT16, HDT29 and HDT52), in the morning at the same time, between 08:00 and 10:00 h.

Retinal images were analyzed by an experimenter blinded to study participants’ characteristics and treatment group (control or intervention). The two retinal images taken at each time point from the participant’s right eye were analyzed using MONA REVA vessel analysis software (version 2.1.1) developed by VITO (Mol, Belgium; http:\vito.be)47,48. Central Retinal Arteriolar Equivalent (CRAE) and Central Retinal Venular Width Equivalent (CRVE) were determined from the retinal images as proxies for retinal blood vessel widths. The following procedure was used to obtain CRAE and CRVE metrics. Consistent retinal regions were obtained across all the fundus images in MONA REVA by defining an annular region centered on the optic disc, with the inner and outer radii of the annulus set at 1.0 and 3.0 times the radius of the optic disc, respectively. Next, the image analysis algorithm based on a multiscale line filtering algorithm automatically segmented the retinal vessels48. Post-processing steps such as double thresholding, blob extraction, removal of small connected regions, and filling holes were performed. The diameters of the retinal arterioles and venules that passed entirely through the circumferential zone 0.5–1 disc diameter from the optic disc margin were calculated automatically. The trained grader verified and corrected vessel diameters and vessel labels (arteriole or venule) with the MONA REVA vessel editing toolbox. The diameters of the 6 largest arterioles and 6 largest venules were used in the revised Parr-Hubbard formula for calculating the central retinal artery equivalent (CRAE) and central retinal venular equivalent (CRVE)32. The CRAE and CRVE values of both images were averaged and used in the statistical analysis.

Cerebrovascular regulation

ECG was acquired using bipolar 3 lead ECG (FD-13, Fukuda Denshi Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) in a standard Lead II electrode configuration. Continuous BP was monitored through a non-invasive Portapres (FMS, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Cerebral blood flow velocity (CBFV) in the M1 segment of the left middle cerebral artery (MCA) was measured using a 2 MHz transcranial Doppler ultrasound probe (DWL MultiDop, Germany). End-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) was monitored with a CO2 gas analyzer (GA200A, iWorx, Dover HN, USA). Data were acquired at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz through a National Instruments USB-6218 16-bit data acquisition platform and Labview 2013 software (National Instruments Inc., TX, USA)28.

Data from five minutes supine or HDBR just after retinal imaging were used for analysis. The R wave peaks of the ECG tracings were marked by an automated computer system and manually reviewed for anomalies and electrode movement artifacts (due to ventilation or cable movement) that may have affected this process. These data were then used to identify beat-by-beat values for arterial blood pressure and CBFV time series. In brief, blood pressure at the level of the MCA (BPbrain), and CBFV waveforms for each beat were used to calculate the mean, systolic, and diastolic values for each signal. The cerebrovascular resistance index (CVRi) was determined beat-by-beat as the ratio of the mean arterial blood pressure (BPMCA) to the mean CBFV (CBFVmean).

Statistical analysis

The retinal, cardiovascular, and cerebral measurements were normally distributed and showed an equal variance. The change in these outcomes over the HDBR study was analyzed by using linear mixed-effects models (SAS for Academics, SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The models included the following fixed effects: time (day of examination), fellow vessel diameter (for retinal measurements only), and nutritional status (control, intervention). To test the effect of the nutritional intervention, we added a time-by-nutritional status interaction term to the model. In both models, each subject was nested within the sequence as a random effect. The interaction term examines the effect of the nutritional status on changes in retinal, cardiovascular, and cerebral measurements, and the random effect accounts for the correlation between repeated measures of the same participant. When analyzing the effect of HDBR on the retinal microvascular and cerebrovascular outcomes at each time point, a Bonferroni post-hoc test was applied to account for multiple comparisons.

Finally, associations between retinal measurements (CRAE and CRVE), participant physical characteristics, and cardio- and cerebrovascular measurements (MCA, CBFV, CVRi) were analyzed by Pearson correlation. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Responses