Risk factors for CAR T-cell manufacturing failure and patient outcomes in large B-cell lymphoma: a report from the UK National CAR T Panel

Introduction

In recent years, CD19-targeting chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T-cell) therapy has become the established standard for patients with relapsed or refractory B-cell malignancies including large B-cell lymphomas (LBCL) [1,2,3], mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) [4] and B-acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (B-ALL) [5, 6]. Though an autologous CAR T-cell product is successfully manufactured for the majority of patients, manufacturing failure (MF) is a significant problem reported in between 1 and 13% of all cases [7, 8] and in up to 25% of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) [9, 10]. It is either because the manufacturing process fails to yield a product or results in one which does not fully comply with the release specification and is deemed an out-of-specification (OOS) product. Similar to other medicinal products, all CAR T cells have a product release specification. This is documented in the marketing authorisation and generally includes minimum cell dose, viability, transduction efficacy, sterility and potency. The specification criteria, aimed at ensuring optimum safety and efficacy, are pre-agreed with appropriate medicines’ regulatory authorities, e.g. the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). It is recognised that due to the specialised nature of the medicines and depending on the nature and degree of non-compliance, it may be that after a careful risk and benefit analysis, administration of an OOS CAR T-cell product remains in the best interest of the patient.

Medicines regulatory processes in the United Kingdom (UK) and European Union (EU) allow for the treating physician to authorise the administration of an OOS CAR T-cell product where the benefit outweighs potential risks [11,12,13]. To facilitate this process, the National Health Service England (NHSE) constituted an OOS CAR T Panel comprising expert CAR T Physicians and Pharmacists.

In the UK, all patients planned for CAR T-cell therapy need initial approval from a national CAR T clinical panel prior to apheresis and CAR T-cell manufacture. In the event of a MF and no product being available, patients may receive delayed infusion after remanufacturing either from the same apheresis product or by repeating apheresis. In some cases, remanufacturing is not attempted, mainly due to deterioration of the patient’s clinical status as a consequence of progressive disease, and patients do not receive CAR T-cell therapy. Where an OOS product is available it may be infused, after approval from the NHSE OOS CAR T Panel. Where the OOS product is not infused, options are the same as for patients without a product. Thus, following MF, there are 3 possible scenarios: patients infused with an OOS product (OOS-infused), those receiving delayed infusion with a product in-specification following remanufacturing (delayed-infused) and those not infused (MF-not-infused).

There is a paucity of data on outcomes for patients following MF with only limited literature on patients infused with an OOS CAR T-cell product [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Even less is known about factors contributing to CAR T MF. Prior bendamustine, low platelet count, a low CD4:CD8 ratio in blood at apheresis and a high CD14+ monocyte count in the apheresis product have all been reported to be associated with MF [10, 22]. Circulating disease, especially a white cell count of >30 × 109/L and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) have also been reported to pose an increased risk of MF in MCL patients [23].

To advance our knowledge, we set out to evaluate the risk factors contributing to CD19-targeting CAR T-cell manufacturing failure and analyse patient outcomes.

Methods

This was a retrospective, multicentre study, with data collected from 9 CAR T centres in the UK. Eligible patients were those with relapsed or refractory LBCL approved for 3rd line or beyond CAR T-cell therapy with axicabtagene ciloleucel (axi-cel) or tisagenlecleucel (tisa-cel) by the UK national CAR T Clinical panel (NCCP) between January 2019 and January 2023. Patients with MF were identified from databases of the participating CAR T centres and from the NHSE OOS CAR T panel.

MF was defined as the non-availability of an in-specification CAR T-cell product. OOS-infused patients were defined as those infused with an OOS product either after initial MF or after one or more remanufacturing attempts. Delayed-infused patients were those who received a delayed infusion with an in-specification CAR T-cell product following remanufacturing. For comparison, we included randomly selected, matched (for CAR T-cell product) LBCL controls without MF, approved for 3rd line or beyond CAR T-cell therapy in the same time period.

All OOS-infused patients were approved for infusion by the NHSE OOS CAR T Panel. This panel is constituted of five expert CAR T Physicians, three expert CAR T Pharmacists and an operations manager. CAR T centres submit OOS applications to the operations manager by email who then forwards them to panel members for review. Panel members perform a detailed risk-benefit assessment taking into consideration the nature and characteristics of the OOS product, clinical status of the patient, speed of disease progression, response to any bridging therapy and ability to repeat apheresis prior to recommending if the OOS product can be infused. For the go-ahead, approval is required from at least four panel members (three Physicians and one Pharmacist). A final decision is communicated back to the CAR T centre by the operations manager, typically within 2–3 days. Though there is some flexibility with most OOS parameters, panel approvals are usually granted if the total viable CAR T-cell dose of the OOS product is within the summary of product characteristics (SmPC) cell dose for each CAR T product.

Baseline risk factors and haematological/biochemical parameters at apheresis for patients with MF and controls were compared using Fisher’s exact/Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney/Kruskal Wallis tests, Chi-squared tests for trend and logistic regression. For patients with prior bendamustine exposure, its timing in relation to apheresis was defined as the interval between day 1 of last cycle and date of apheresis. Overall response rate (ORR) and complete response (CR) were assessed as per Lugano criteria [24] by PET-CT scan at 1- and 3 months post CAR T-cell infusion in all patients. Further PET-CT scans were performed at the discretion of treating physician for patients not in a CR or when there was clinical concern for disease progression.

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from approval for CAR T-cell therapy (irrespective of whether a patient was infused with CAR T-cell product or not) until death from any cause. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as the time from the date of CAR T-cell infusion until disease progression or death from any cause. PFS was only analysed for infused patients as pre-CAR T-cell infusion dates of progression were not always recorded and to avoid counting progression between approval and CAR T-cell infusion as an event. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome (ICANS) were assessed as per ASTCT consensus criteria [25], and cytopenias were graded as per CTCAE criteria [26]. Outcomes were compared using Cox regression and Kaplan–Meier Survival analysis (PFS, OS) and Fisher’s exact tests (response/toxicity). The assumption of proportional hazards was checked using the Schoenfeld residuals.

Results

Patient and CAR T product disposition

In total, 981 LBCL patients were approved for CAR T-cell therapy (axi-cel 805, tisa-cel 176) between January 2019 and January 2023. We identified 38 patients who had at least 1 CAR T-cell MF. The intended CAR T-cell product was axi-cel in 28 and tisa-cel in 10 patients. Overall MF frequency was 3.9% (3.5% for axi-cel and 5.7% for tisa-cel). To analyse MF risk across different time periods, we compared MF frequency in era 1 (January 2019–January 2021) with era 2 (February 2021–January 2023). There was no difference by time period with MF frequency of 17/462 (3.6%) in era 1 and 21/519 (4.0%) in era 2 (P = 0.74).

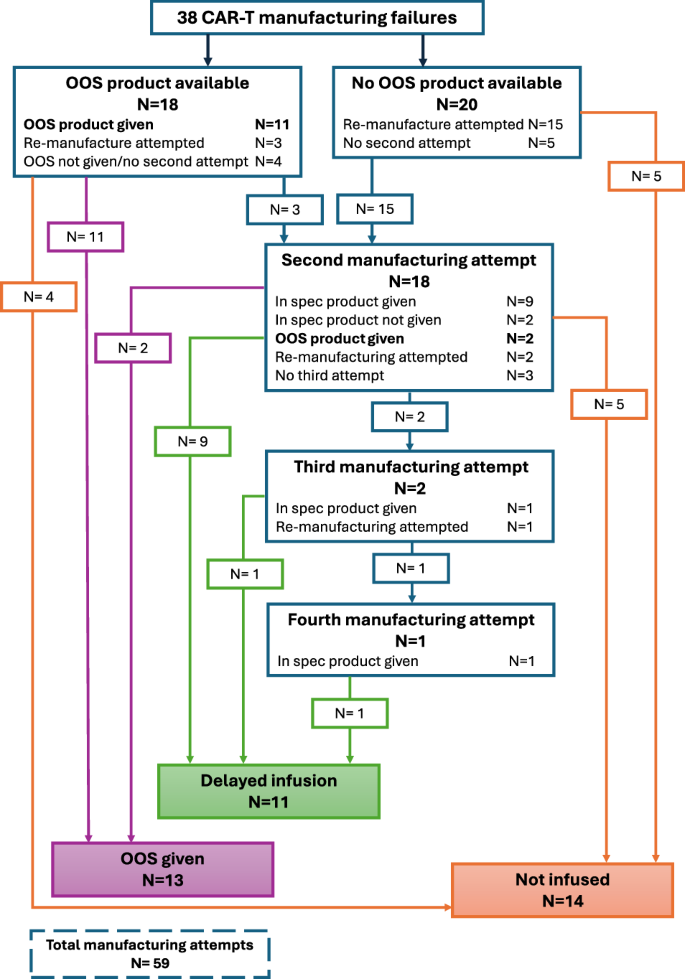

The number of manufacturing attempts and resulting product outcomes are shown in the flow diagram (Fig. 1). Details of the reasons for MF per patient and per manufacturing attempt are shown in Supplementary Table 1. All 38 patients had an MF after the 1st manufacturing attempt (OOS in 18 and no product available in 20). Some of these went on to have further manufacturing attempts from either the same apheresis material or by repeating apheresis. In the end, a total of 59 manufacturing attempts were made for the 38 patients; 20 resulted in an OOS product (18 after 1st and 2 after 2nd attempt) 13 of which were infused, 13 produced a product in-specification after one or more remanufacturing attempts (11 after 2nd, 1 after 3rd and another after 4th attempt) 11 of which were infused and 26 resulted in no product being available (20 after 1st, 5 after 2nd and 1 after 3rd attempt). Analysing the 46 manufacturing attempts resulting in either an OOS product or no product, the most frequent reasons for MF were low cell viability (n = 8), low T-cell purity (n = 8), poor growth in culture (n = 6), low interferon-gamma (n = 6) and low CAR T-cell dose (n = 4). Most frequent reasons for MF with an available OOS product were low cell viability (n = 5), low interferon-gamma (n = 5) and low T-cell purity (n = 4) (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). Although numbers were limited, analysing reasons for MF over time did not reveal any obvious differences between era 1 and era 2 (Supplementary Table 2).

Flow diagram of patients with an initial CAR T manufacturing failure showing further manufacturing attempts and product outcomes.

Of the 38 patients with MF, OOS product was infused in 13 patients (OOS-infused cohort) following approval from the NHSE OOS CAR T panel; 11 patients went on to receive a delayed infusion with an in-specification CAR T-cell product (delayed-infused cohort) and 14 patients did not proceed to CAR T-cell infusion (MF-no-infusion cohort) (Fig. 1). For comparison with the 38 MF patients, we included 38 randomly selected LBCL controls matched for CAR T-cell product (28 axi-cel and 10 tisa-cel) without MF, 29 of whom received infusion (controls-infused cohort).

Risk factors for MF

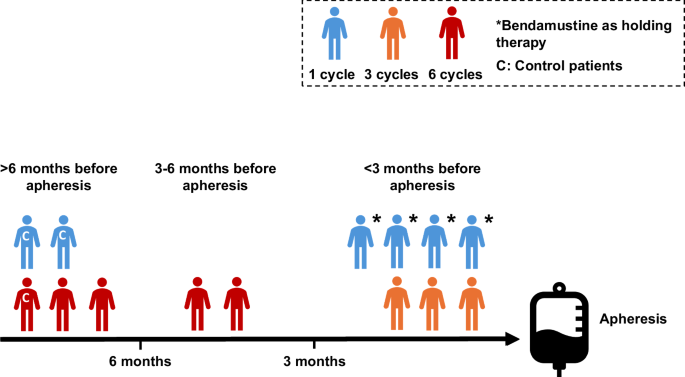

An assessment of baseline variables and their impact on risk of MF is shown in Table 1. There was no difference in age, sex, BMI, number of prior lines of therapy, prior high-dose cytarabine, prior stem cell transplant or the need for holding therapy between MF patients and controls. Bendamustine therapy was the only baseline variable significantly associated with risk of MF with prior exposure in only 3 out of 38 (7.9%) controls compared with 11 out of 38 (28.9%) MF patients (P = 0.026). In all but 2 patients, bendamustine was administered as part of the rituximab, polatuzumab and bendamustine regimen. Two patients had prior bendamustine (one each with rituximab and obinutuzumab) for follicular lymphoma. The increased risk with bendamustine appeared to be largely due to therapy within 6 months; with 0% of controls vs 9 of 38 (23.7%) of MF patients (P = 0.0029) receiving it within 6 months of apheresis (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). We went on to analyse the impact of the number of bendamustine cycles received on the risk of MF. We found a significant association between bendamustine timing and the number of cycles received (P = 0.021), with patients given bendamustine closer to apheresis having received fewer cycles in total; of the 11 MF patients with prior bendamustine, 7 received it within 3 months of apheresis; 4 received only 1 cycle (all as holding therapy) and the others received 3 cycles (Fig. 2). Therefore, we were not able to evaluate the effect of number of cycles of bendamustine on risk of MF as it was confounded by the timing of delivery.

Association between timing of bendamustine in relation to apheresis and number of cycles received.

Assessment of variables at apheresis, including biochemical and haematological parameters, and their impact on risk of MF is shown in Table 2. None of the variables analysed, including total white cell count, absolute neutrophil, absolute lymphocyte count, platelet count, CD3 count, LDH, CRP and volume of blood apheresed were significantly associated with a risk of MF. As bendamustine was the only baseline variable associated with a risk of MF, we further analysed the impact of recent bendamustine (<6 months) on blood counts at apheresis (Table 3). Apart from a lower platelet count of borderline statistical significance (P = 0.051), there was no difference in any other parameter between those exposed to recent bendamustine vs those not.

Efficacy outcomes

Median follow-up from approval for CAR T-cell therapy was 25.2 months (IQR: 18–35.6) for patients with MF and 35.9 months (IQR: 28.7–49.5) for controls. Median (IQR) time from approval for CAR T-cell therapy to infusion was 63 (57–69), 85 (70–119) and 62 (48–71) days for OOS-infused, delayed-infused and controls-infused patients. Baseline characteristics of infused CAR T patients is shown in Table 4, there were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between the infused cohorts (OOS-infused, delayed-infused and controls-infused).

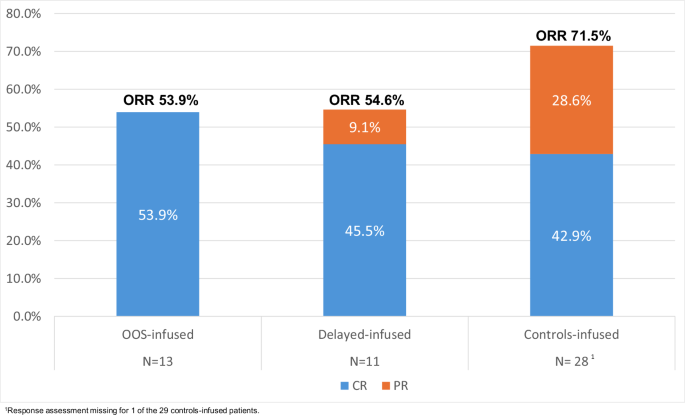

ORR and CR were assessed by PET-CT scans at 1- and 3 months post infusion. Best ORR (CR) rates were 53.9% (53.9%), 54.6% (45.5%) and 71.5% (42.9%) for OOS-infused, delayed-infused and controls-infused, respectively (Fig. 3). Corresponding best ORR and CR rates by CAR T-cell product are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, although numbers are too small to test for any differences in response rates by product. ORR (CR) rates at 1 month post infusion were 53.9% (53.9%), 54.6% (45.5%) and 71.4% (32.1%) and at 3 months were 46.2% (46.2%), 27.3% (27.3%) and 57.1% (39.3%) for the OOS-infused, delayed-infused and controls-infused cohorts respectively. There were no significant differences in the response rates between the three infused cohorts (P = 0.47 and P = 0.26). There was no suggestion for a delay in time-to-CR in either the OOS-infused or delayed-infused cohorts. All patients achieving a CR in both cohorts did so by 1 month post infusion.

Best response post CAR T infusion.

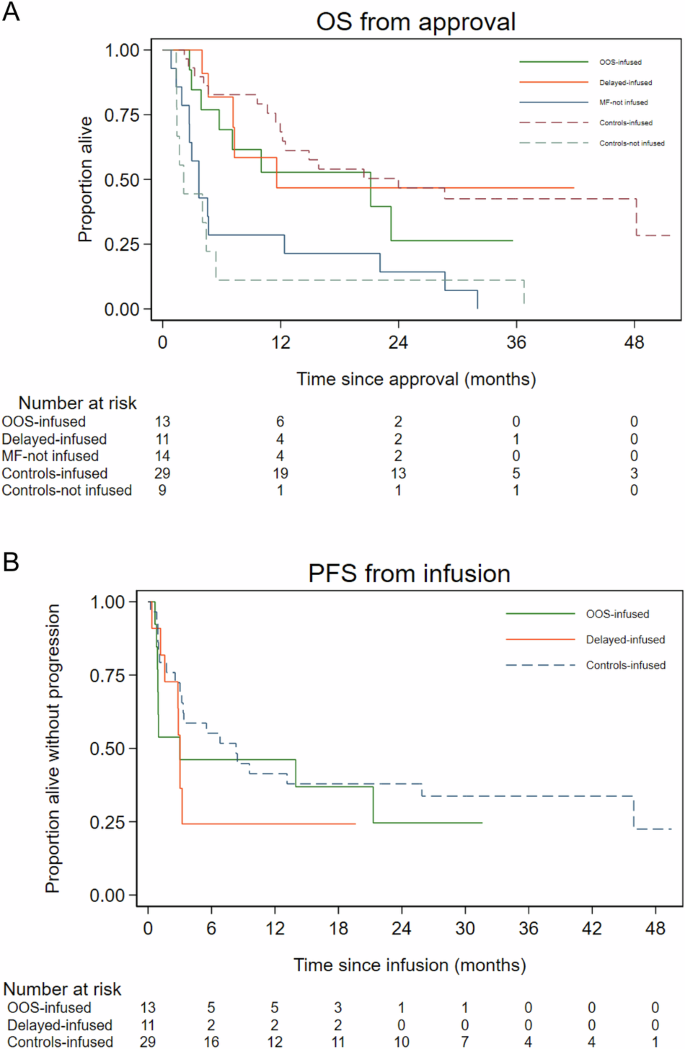

The 1-year OS (95% CI) from approval for OOS-infused, delayed-infused and controls-infused patients was 52.8% (23.4–75.5), 46.8% (14.8–73.9) and 68.4% (48.0–82.1) respectively with no significant difference between OOS-infused and controls-infused patients (HR: 1.52 (95% CI 0.65–3.58), P = 0.34), between delayed-infused and controls-infused patients (HR: 1.13 (95% CI 0.41–3.11), P = 0.81) or between OOS-infused vs delayed-infused (HR: 0.74 (0.24–2.28), P = 0.61). As expected, OS for non-infused patients (both for MF-not-infused and controls-not-infused) was poor with 1-year OS (95% CI) rates of 28.6% (8.8–52.4) and 11.1% (0.6–38.8), respectively (Fig. 4A).

A Overall survival (OS) from approval for CAR T. B Progression-free survival (PFS) from infusion.

The 1-year PFS (95% CI) for OOS-infused, delayed-infused and controls-infused patients was 46.2% (19.2–69.6), 24.2% (4.4–52.5) and 41.4% (23.7–58.3) respectively with no significant difference for OOS-infused vs controls-infused (HR 1.41 (95% CI 0.64–3.13), P = 0.40), for delayed-infused vs controls-infused (HR 1.64 (95% CI 0.70–3.83), P = 0.25) or for OOS-infused vs delayed-infused (HR: 0.86 (95% CI: 0.333–2.25), P = 0.76) (Fig. 4B). PFS for the three infused cohorts by CAR T-cell product is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, although patient numbers are too small for any statistical comparisons to be performed.

Safety outcomes

In OOS-infused, delayed-infused and controls-infused patients, CRS of any grade (and grades 3–4) was seen in 83.3% (15.4%), 90.9% (0%) and 93.10% (6.90%), respectively, with no significant differences between the three infused cohorts either for any grade CRS (P = 0.81) or grades 3–4 CRS (P = 0.50). Corresponding rates for ICANS of any grade (and grades 3–4) were 38.5% (7.7%), 30.0% (18.2%) and 34.50% (10.30%), respectively, once again with no significant differences between the three infused cohorts either for any grade ICANS (P > 0.99) or grades 3–4 ICANS (P = 0.72).

The incidence of grades 3–4 neutropenia at 1 month (and 3 months) post CAR T-cell infusion was 16.7% (20.0%), 44.4% (40.0%) and 29.20% (19.05%) for OOS-infused, delayed-infused and controls-infused patients, respectively (P = 0.62 at 1 month and P = 0.81 at 3 months). Corresponding incidence of grades 3–4 thrombocytopenia at 1 month (and 3 months) was 33.3% (20.0%), 40.0% (20.0%) and 25.00% (4.80%) (P = 0.63 at 1 month and P = 0.24 at 3 months). There were no significant differences in cytopenia rates at either timepoint, though numbers assessable (alive without progression) at each point were small.

There were 4 deaths in remission, 1 in the OOS group at 21 months post CAR T (cause unknown, but after diagnosis of MDS), 3 in the control group (2 COVID at 13.1 and 45.9 months and 1 unknown cause at 8.4 months).

Discussion

Here we report a detailed analysis of risk factors contributing to CAR T-cell manufacturing failure in LBCL patients as well as their outcomes compared with matched controls. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive analysis assessing outcomes for all possible scenarios following MF. We included all LBCL patients with MF planned for treatment with either axi-cel or tisa-cel (products currently approved in the UK).

To be able to assess impact of baseline factors on the risk of MF, we kept matching variables to a minimum when selecting matched LBCL controls. Prior bendamustine within 6 months of apheresis was the only baseline variable associated with a risk of MF in our study. Bendamustine as a risk factor for tisa-cel MF has been reported in a cohort of LBCL patients from Japan; risk was particularly high for those receiving >3 cycles with <3 months washout to apheresis [22]. We were unable to assess the impact of the number of bendamustine cycles as there was a significant association between the timing of bendamustine in relation to apheresis and number of cycles received, though this confounding effect highlights that even a small number of cycles may confer an increased risk of MF. Of note, a recent study found significant correlation between prior bendamustine within 9 months of apheresis, (but not the cumulative number of cycles received), and inferior outcomes post CAR T-cell therapy in LBCL patients [27].

Prior bendamustine is also reported to be associated with a low CD4 (but not CD8) count at apheresis [27] and an attenuated T-cell function [4]. Both a low CD4:CD8 T-cell ratio and a low platelet count were reported to be associated with an increased risk of MF in the Japanese cohort [22]. None of the haematological or biochemical parameters including the absolute lymphocyte and total CD3 count at apheresis conferred a risk of MF in our study, but our analysis is limited by lack of data on CD4 and CD8 T-cell subsets. There are also other differences between the studies. The Japanese study was confined to tisa-cel MF and used a more restrictive definition for MF, as only patients with no product available were included. Our study included both axi-cel and tisa-cel patients, with a majority of axi-cel, and we used a more holistic definition for MF, encompassing both patients with no product and those with an OOS product and were thus able to capture a broader range of scenarios. Though we were not able to evaluate T-cell function at apheresis due to the retrospective nature of our study, our observation would be in keeping with the adverse impact of bendamustine on CAR T-cell manufacture being mediated by an effect on T-cell function rather than total CD3 numbers. Whilst we did not find any correlation between markers of aggressive disease and risk of MF, our analysis is limited by lack of data on some markers of aggressive disease such as stage at relapse, IPI, extranodal sites and metabolic tumour volume.

It is important to note that our study included patients approved for 3rd line or beyond CAR T-cell therapy. It is possible that the risk of MF may be different in less heavily pre-treated patients planned for 2nd line CAR T-cell therapy who are unlikely to have received prior bendamustine. Another limitation is that we have only assessed clinical and laboratory parameters possibly impacting on manufacturing. We were unable to assess variables in the manufacturing process itself which may be important determinants of manufacturing success.

There is currently a paucity of data on outcomes of patients following CAR T-cell MF. Patients with B-ALL infused with OOS tisa-cel due to low cell viability were reported to have comparable outcomes to those receiving a product in-specification with >80% cell viability [14,15,16,17,18,19]. However, for patients with LBCL there are contradictory reports with some suggesting no difference [20] and others showing a trend to inferior response rates and survival [18]. The ZUMA-9 study reported reduced CAR T-cell expansion and lower CR rates in 36 LBCL patients infused with OOS axi-cel. OOS causes were, a low cell viability in 50%, high interferon-gamma in 28%, low interferon-gamma in 14%, high transduction ratio in 6% and a low viable CAR T-cell dose in 14% [21]. These studies have all reported outcomes for patients infused with an OOS CAR T-cell product but not for patients where a product was not available.

In our study, we were able to assess outcomes for all possible scenarios following MF including patients infused with an OOS product, those receiving a delayed infusion with an in-specification product following further remanufacturing attempts and those not infused. Of note, we did not find any significant differences in either ORR, CR, OS or PFS between OOS-infused, delayed-infused and controls-infused. A 12-month OS of 52.8% and PFS of 46.2% for OOS-infused patients is reassuring and supports infusing patients with an OOS product where one is available. Whilst it is possible that outcomes may be different based on the reason for a product being OOS, we are unable to perform this analysis due to the small numbers of patients. It is also important to note that the total viable CAR T-cell dose was within product specification for all but one OOS-infused patient in our study as this is an important pre-requisite for approval by the NHSE OOS CAR T Panel. It is therefore unknown if our results can be extrapolated to OOS products with a significantly low total viable CAR T-cell dose. The three infused cohorts in our study were comparable for a number of baseline variables but we were not able to match for all factors likely to impact on outcomes.

Though patients receiving a delayed infusion have reasonable outcomes in our study (12-month OS 46.8%), it is possible these are enriched for patients with non-progressive or low tumour burden disease or disease which is responsive to treatment. However, it is noteworthy that their ORR and CR at 3 months of 27.3% and 12-month PFS of 24.2% were much lower than for the other cohorts though not reaching statistical significance, probably due to the small sample size. The lower response rate and PFS in this cohort could be due to disease progression/ higher tumour burden at infusion due to delay in infusion as a result of remanufacturing attempts. It is also important to note remanufacturing led to successful infusion with an in-specification product in only around 50% of attempts in our study, suggesting that the delayed-infused cohort is a select group of patients. Our results therefore support proceeding to an infusion where a suitable OOS product is available. Delaying infusion and attempting remanufacturing may be an option reserved for selected patients where an OOS product is not available.

Similar to the findings reported from previous studies [14, 21], we did not find any significant difference in toxicity between infusion with an OOS or in-specification products. We acknowledge that our study is limited by small numbers and statistically underpowered to detect a true difference for some comparisons.

Our results suggest encouraging outcomes for patients infused with an OOS product comparable to control patients without manufacturing failure infused with a product in-specification. Remanufacturing led to infusion of a product in-specification only in around 50% of attempts. There was no difference in the incidence of CRS or ICANS and grade 3–4 cytopenias. Prior bendamustine within 6 months of apheresis was the only variable associated with the risk of MF.

Responses