Robust quantum spin liquid state in the presence of giant magnetic isotope effect in D3LiIr2O6

Introduction

Quantum spin liquid (QSL) represents a novel quantum state of matter where interacting spins remain disordered down to zero temperature and harbors a topologically nontrivial state with fractionalized excitations1,2. In two-dimensional magnets, since the proposal of the resonating valence bond (RVB) state by P. W. Anderson for the S = 1/2 Heisenberg antiferromagnet on a triangular lattice3, a variety of theoretical models has been put forward to realize a QSL state. Among those, the S = 1/2 bond-dependent Ising model on a honeycomb lattice proposed by A. Kitaev4 is distinct from the other two-dimensional models in that it is exactly solvable. By introducing two kinds of Majorana operators4, the ground state of the Kitaev model was shown to be a QSL consisting of an ensemble of itinerant and localized Majorana fermions. The Kitaev model and its QSL ground state have been attracting considerable interest recently.

The essential ingredient of the Kitaev model is the competing Ising interactions with their easy-axis orthogonal to each other on the three 120° bonds of honeycomb lattice4. Such bond-dependent Ising couplings have been theoretically proposed to be realized in iridium (Ir4+) oxides (iridates) and a ruthenium (Ru3+) chloride with an edge-shared honeycomb network of IrO6 and RuCl6 octahedra5. In the family of Ir4+ oxides with five 5d electrons, the cubic crystal field overcomes Hund’s first rule, and all the five 5d-electrons are accommodated in the t2g manifold. Strong spin-orbit coupling λSO of Ir, as large as 0.5 eV, entangles spin and orbital degrees of freedom, yielding a fully-filled lower Jeff = 3/2 quartet and a half-filled upper Jeff = 1/2 doublet out of the triply-degenerate t2g orbitals6. A spin-orbit-entangled Mott state with localized Jeff = 1/2 pseudospins can be stabilized only with a modest on-site Coulomb interaction of a few eV between 5d electrons7. When the two neighboring IrO6 octahedra are connected by sharing their edges, bond-dependent ferromagnetic Ising coupling between the two Jeff = 1/2 pseudospins appears through a super-exchange process in the Ir-O2-Ir planar bonds5. If the other magnetic couplings than this super-exchange coupling can be ignored, the Kitaev model is realized in the edge-shared honeycomb network of IrO6 octahedra, leading to a quantum liquid state of spin-orbit-entangled pseudospins (denoted QSL hereafter for brevity).

The layered iridates Na2IrO3 and α-Li2IrO38,9 and α-RuCl310 with edge-shared honeycomb networks of IrO6 (RuCl6) octahedra, and later their three-dimensional analogs β– and γ-Li2IrO311,12, have been considered as candidates to realize the Kitaev model and the QSL state. However, all those candidate materials were found to undergo either a zigzag or a spiral magnetic ordering at low temperatures13,14,15,16. The appearance of magnetic ordering rather than a QSL state is most likely attributable to the superposition of other types of magnetic interactions on the Kitaev coupling, such as antiferromagnetic Heisenberg coupling due to direct d–d overlap, symmetry-allowed off-diagonal exchange and further-neighbor interactions17,18,19. Nevertheless, the predominance of Kitaev coupling and the proximity to the Kitaev QSL state has been argued both experimentally and theoretically20,21,22.

In contrast to the aforementioned candidates, the protonated honeycomb iridate H3LiIr2O6 was discovered to host a QSL ground state23. H3LiIr2O6 is obtained by a soft-chemical substitution on α-Li2IrO324,25. H+ ions replace all of the Li+ ions in the interlayer sites but not those in the honeycomb layers of α-Li2IrO3, which leaves the LiIr2O6 layer units intact. The Curie-Weiss behavior of magnetic susceptibility at high temperatures evidences the presence of localized and interacting spin-orbit-entangled Jeff = 1/2 moments. The negative Curie-Weiss temperature, θCW ~ −100 K, points to the sizable antiferromagnetic couplings23, very likely the superposition of more than one kind of interaction, such as Kitaev, Heisenberg, and off-diagonal interactions. Despite those magnetic interactions, H3LiIr2O6 does not show any sign of magnetic ordering or spin-glass freezing in the specific heat and the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements down to 50 mK, which is indicative of a QSL ground state. However, any clear evidence for the Kitaev-type QSL, including the signature of localized and itinerant Majorana fermions, has been lacking so far. The specific heat at low temperatures below 1 K was found to be dominated only by a T3-term, which very likely represents the lattice contribution, indicating a gap in the spin excitations23. This suggests that the QSL state of H3LiIr2O6 is at least away from the pure Kitaev limit, and some mechanism suppressing competing long-range magnetic order should be operative behind the QSL state.

The formation of the QSL state in H3LiIr2O6, in sharp contrast to the other honeycomb iridates and the ruthenium chloride, brought our attention to the role of interlayer protons, a structural ingredient distinct from the other honeycomb iridates. We examined the H/D isotope effect to experimentally capture the role of the OH bond by synthesizing the deuterium-substituted compound D3LiIr2O6. The structural refinements based on the neutron diffraction measurements revealed the presence of covalent OD bonds with oxygen atoms either above or below the deuterium plane, as well as the large structural isotope effect in the OD and OH bonds. A gigantic isotope effect on the magnetic interactions was discovered, indicating the unexpectedly large influence of OD/OH bonds on the magnetic couplings. The antiferromagnetic Curie-Weiss temperature |θCW| of D3LiIr2O6 was found to be enhanced substantially to ~170 K from ~100 K of H3LiIr2O6. Nevertheless, D3LiIr2O6 was found to host a QSL state of Jeff = 1/2 pseudospins as in H3LiIr2O6. The contrast of the OD/OH bonds should account for the large isotope effect on the magnetic interactions governed by the super-exchange process through the oxygen 2p orbitals. Random distribution of the O-D-O (or O-H-O) bond structures in the two materials very likely gives rise to bond-disorder in the in-plane magnetic interactions of the Jeff = 1/2 moments, which we argue may be one of the important ingredients to stabilize the QSL state in D3LiIr2O6 and H3LiIr2O6.

Results

Crystal structure

The powder sample of D3LiIr2O6 was synthesized from α-Li2IrO3 by an ion-exchange technique as described in “Methods”. The powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) indicated that the product comprised a single phase of D3LiIr2O6 crystallizing in the same layered honeycomb structure as H3LiIr2O6 (see Supplementary Fig. S1 for the PXRD pattern). The presence of strong stacking fault disorder was identified in the PXRD pattern as in H3LiIr2O624. All the interlayer Li+ ions of α-Li2IrO3 are replaced by D+ ions within the given resolution of our experiments. Unlike α-Li2IrO3, O2- ions in the top and the bottom layers of the adjacent LiIr2O6 honeycomb layer face each other and form nearly straight O-D-O units24.

The comparison of the PXRD pattern with that of H3LiIr2O6 indicates a large structural isotope effect. The shift of 001 reflections is clearly seen in the PXRD pattern (Fig. 1b), which corresponds to the increased distance between the Ir-honeycomb planes (d001) by ~1% via deuteration. The lattice parameter c at room temperature estimated from the neutron diffraction measurements described below is c = 4.884(2) Å for H3LiIr2O6 and c = 4.916(6) Å for D3LiIr2O6, respectively. A similar gigantic structural isotope effect from the interlayer H+/D+ ions was observed in layered oxides such as H(D)CrO226,27, which has been ascribed to the distinct character of the interlayer O-H-O and O-D-O bonds. The H+ or D+ ion placed between the two O2- ions experiences double-well potential. While the D+ ion is very likely trapped at one of the potential wells, the H+ ion is argued to delocalize over the two possible positions due to the pronounced quantum tunneling effect26,27,28.

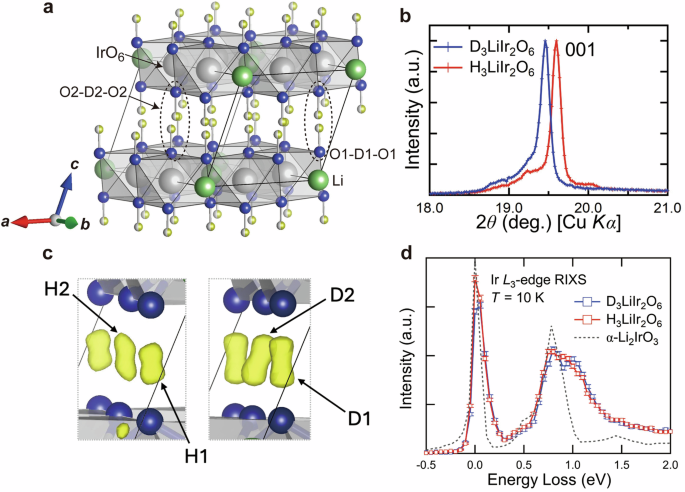

a Crystal structure of D3LiIr2O6 (space group C2/m) refined from the neutron diffraction data. The gray, blue, light green, and yellow spheres show iridium, oxygen, lithium, and deuterium atoms, respectively. Two different O-D-O bonds are indicated by dotted circles. There are two possible positions for each D atom, and the occupancy of each position is 0.5. The refined structural parameters are listed in Table 1. b Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns for D(H)3LiIr2O6 near 001 reflection, highlighting the structural isotope effect. The PXRD patterns were recorded using Cu-Kα radiation. The distance of (001) planes, d001, estimated from PXRD, is ~4.559 Å for D3LiIr2O6 and ~4.526 Å for H3LiIr2O6, respectively. c Difference Fourier map of O-H-O interlayer bonds in H3LiIr2O6 (left) and the O-D-O bonds in D3LiIr2O6 (right) from the neutron diffraction measurements. While the D atoms have a large occupational probability close to the oxygen atoms, the H atoms reside near the center of O-O bonds. This may reflect the more dynamic character of H+ ions due to the quantum tunneling effect. d Ir L3-edge RIXS spectra for D(H)3LiIr2O6 recorded at T = 10 K. The dotted line shows the spectrum of α-Li2IrO3 obtained in the same experimental condition for comparison. The spectra are normalized by the intensity of elastic lines.

Such distinct characteristics of the interlayer bonds may also be present in H3LiIr2O6 and D3LiIr2O6. The experimental determination of the position of D+ or H+ ions, however, was not feasible in the PXRD because of its weak X-ray scattering factor. To determine their positions, the neutron diffraction measurement was conducted on the powder sample enriched with 7Li- and 193Ir-isotopes29. The use of 7Li and 193Ir reduces the absorption of neutrons by a factor of ~4. The refined structural parameters for D3LiIr2O6 are listed in Table 1 (see Supplementary Fig. S2 for the powder neutron diffraction patterns), and the corresponding crystal structure is illustrated in Fig. 1a. There are two crystallographic sites for deuterium, D1 and D2, forming the O1-D1-O1 and O2-D2-O2 bonds between the honeycomb layers with the two inequivalent oxygen sites O1 and O2, respectively. The O1-D1-O1 bond is nearly perpendicular to the honeycomb plane. The configuration of the O2-D2-O2 bond is essentially the same as that of O1-D1-O1 but more tilted with respect to the honeycomb plane. We will not distinguish the two bonds explicitly in this paper. The refinement indicates that each D ion has two possible off-center positions, above and below the center, between the two oxygen atoms facing each other (see Supplementary Note 1 for details of the refinements). This contrasts with the symmetric positions of interlayer cations in other delafossite-type oxides such as Ag3LiIr2O630. The estimated occupancies of the two off-center positions are 50% each, which naturally means that only one of the two off-center positions between two O atoms is randomly occupied by D atoms. The simultaneous occupation of the two off-center positions is highly unlikely due to electrostatic repulsion. D atoms form a short OD bond of ~1 Å with one of the O atoms, as short as that in D2O31. The distance to the other oxygen atom is as large as ~1.6 Å. These strongly suggest that a D atom between the two oxygen atoms forms a rigid covalent bond with one and a hydrogen bond with the other, such as O-D···O or O···D-O, where – and ··· denote a covalent and a hydrogen bond, respectively. The O-D···O and O···D-O bonds are distributed randomly, and no signature of layer ordering of O-D···O and O···D-O bonds in the interlayer plane was found in the refinement.

The refinement of neutron diffraction data on the isotope-enriched H37Li193Ir2O6 (Supplementary Fig. S3) also indicates the two off-center positions for H+ ions as in the deuterated analog. The refined structural parameters are listed in Supplemental Table S1. Nonetheless, we found signatures of the different characters of O-H-O bonds. The difference Fourier maps for the O-H-O and O-D-O bonds depicted in Fig. 1c highlights the contrast of the two bonds. The Fourier map for the O-D-O bond shows a large occupational probability of the D ions close to either of two O atoms, whereas that of the O-H-O bonds showed that H+ ions reside close to the center of O-O bonds. This difference is manifested in the slightly shorter length of the O-D bonds (d(O1-D1) = 1.001(8) Å, d(O2-D2) = 1.024(12) Å) than the O-H bonds (d(O1-H1) = 1.017(17) Å, d(O2-H2) = 1.026(10) Å) and naturally explains the large structural isotope effect. In addition, the refined isotropic displacement parameter for H atom, Uiso ~ 0.0177 Å2, is larger than those of D atom (Uiso ~ 0.0124 Å2). These suggest that H+ ions have more dynamical character and are possibly tunneling between two off-center positions, as discussed in HCrO226,27. In the case of H3LiIr2O6, however, the strong stacking fault disorder24 should disturb the coherent alignment of oxygen atoms above and below, which may hinder the tunneling and trap a H+ ion at one of the off-center positions inhomogeneously.

Compared to the large isotope effect on the interlayer bonds, the impact of deuteration on the LiIr2O6 honeycomb layer is not as significant as the interlayer distance. Both H3LiIr2O6 and D3LiIr2O6 have strongly compressed IrO6 octahedra. The Ir-O-Ir angles of ~100° are nearly the same in both compounds, as the elongation of the c-axis in D3LiIr2O6 is mostly attributed to the enlarged O-O distance between the LiIr2O6 honeycomb layers by ~2%. The in-plane lattice parameter b(a) increases(decreases) only by ~0.1(0.05)% by deuteration, respectively. Therefore, the local electronic structure should not be modified substantially by the isotope exchange, which was confirmed by resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) measurement described below.

Electronic and magnetic properties

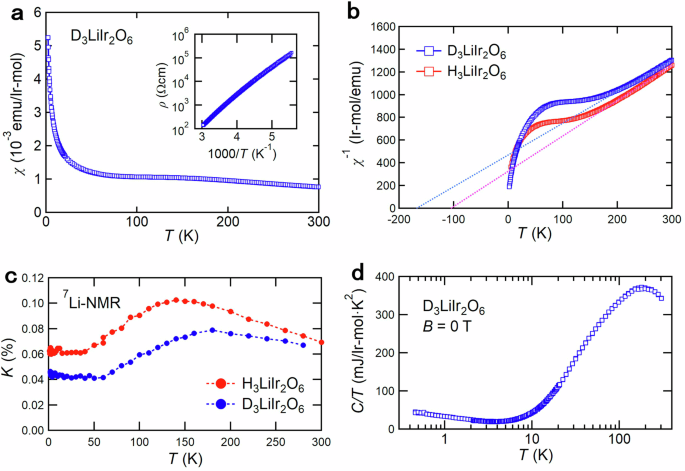

The resistivity measurement showed that D3LiIr2O6 is an insulator with an activation gap of ~0.1 eV as shown in the inset of Fig. 2a, a typical value for an Ir4+ Mott insulator23. Magnetic susceptibility χ(T) displays a Curie-Weiss behavior at high temperatures (Fig. 2a). The Curie-Weiss fit above 250 K, shown in Fig. 2b, yields an effective moment of ~1.69 μB/Ir, which is very close to that of Jeff = 1/2 moment. These provide the support that D3LiIr2O6 is a spin-orbit-entangled Mott insulator with localized Jeff = 1/2 pseudospins as in H3LiIr2O6.

a Temperature dependence of magnetic susceptibility χ(T) measured at a magnetic field of 1 T. The inset shows the Arrhenius plot of resistivity ρ(T). b Inverse of χ(T) for D3LiIr2O6 and H3LiIr2O6 displaying the isotope effect on the magnetic interactions. The Curie-Weiss temperature changes from ~ −100 K for H to ~ −170 K for D. c 7Li Knight shift K(T) of D3LiIr2O6 and H3LiIr2O6 measured at a magnetic field of 2 T. The broad hump of K(T) appears at a higher temperature in D3LiIr2O6 than that in H3LiIr2O6. d Specific heat divided by temperature C(T)/T for D3LiIr2O6 at zero magnetic field. The nuclear Schottky contributions at low temperatures were removed by the method described in ref. 23. No magnetic order was found down to 50 mK.

The Ir L3-edge RIXS spectrum shown in Fig. 1d is consistent with the Jeff = 1/2 picture. D3LiIr2O6 exhibits two excitation peaks at ~0.78 eV and ~1.04 eV, which can be ascribed to an intra-atomic excitation from Jeff = 1/2 to 3/2 states (in the hole description). A similar peak has been observed around ~0.7 eV in the RIXS spectra of a number of iridates32,33, which corresponds to the split of Jeff = 1/2 and 3/2 states, namely 3/2λSO. The double-peak structure observed in D3LiIr2O6 is very likely ascribed to the split of Jeff = 3/2 states by the trigonal crystal field associated with the compression of IrO6 octahedra along the c-axis. The comparison of the double-peak structure with those in α-Li2IrO3 and H3LiIr2O6 indeed indicates the intimate correlation between the peak split in the RIXS spectra and the trigonal structural distortion. While D3LiIr2O6 with a large trigonal distortion shows a clear double-peak structure with the splitting of ~0.25 eV, α-Li2IrO3 with a moderate trigonal distortion shows only broadening within the experimental resolution. Comparing the spectra of D3LiIr2O6 and H3LiIr2O6, the splitting appears to be not appreciably different, at most only marginally larger for D3LiIr2O6 (see Supplementary Note 2 and Fig. S4). This is consistent with the comparable or only slightly larger trigonal distortion for D3LiIr2O6.

While the deuterium isotope exchange does not have any appreciable impact on the electronic structure on eV scale, it gives rise to an unexpectedly large change of the low-energy magnetic interactions, which can be seen clearly in the comparison of magnetic susceptibility χ(Τ) of D3LiIr2O6 with that of H3LiIr2O6 (Fig. 2b). From the Curie-Weiss fit above 250 K, an antiferromagnetic Curie-Weiss temperature, θCW ~ −170 K, is estimated for D3LiIr2O6, which is almost a factor of two larger than that of H3LiIr2O6, θCW ~ −100 K23, pointing to much enhanced antiferromagnetic interactions. With decreasing temperature below 250 K, χ(T) displays a broad hump at around 180 K, which can be regarded as a temperature scale for the development of antiferromagnetic correlations. Consistent with the enhancement of |θCW | , the hump temperature of 180 K is much higher than ~130 K for H3LiIr2O6. The enhancement of hump temperature in the uniform susceptibility can be recognized more clearly in the Knight shift K(T) from 7Li-NMR (Fig. 2c), where Curie-like contributions from spin defects are absent.

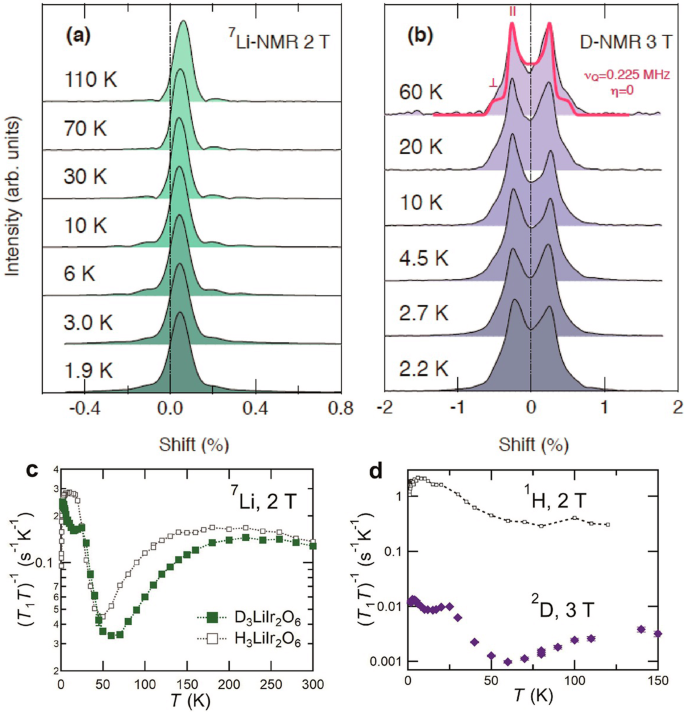

The information about spin dynamics obtained by the spin-lattice relaxation time T1 of NMR corroborates the gigantic H/D isotope effect on χ(T) and K(T) (Fig. 3c, d). On cooling from room temperature, (T1T)-1 for 7Li shows a slight increase in accord with the Curie-Weiss behavior of χ(T) and then shows a broad hump around 230 K followed by a decrease. The (T1T)-1 hump temperature is appreciably higher than that of H3LiIr2O6, ~180 K23. As 7Li atoms reside at the center of the Ir-honeycomb lattice and the nuclei experience hyperfine fields from the six surrounding Ir4+ ions, the decrease of (T1T)-1 very likely derives from the cancelation of the hyperfine fields by the development of antiferromagnetic correlations over an Ir hexagon. Hence, the higher (T1T)-1 hump temperature of D3LiIr2O6 also indicates enhanced antiferromagnetic interactions upon deuteration.

a 7Li- and b 2D-NMR spectra. The solid vertical line is a guide for spectral positions without any internal fields. The split of spectra in 2D-NMR originates from the nuclear electric quadrupole splitting for a nuclear spin I = 1. The red solid line shows a powder pattern fitted with a single set of quadrupole parameters, νQ = 0.225 MHz and η = 0, where νQ equals to 3/2 × e2qQ/h for I = 1 (e2qQ/h is the deuterium quadrupole coupling constant) and η is the asymmetry parameter, respectively61. The shoulder-like structure is attributable to the quadrupolar interactions in the randomly oriented powder sample. c Temperature dependences of the inverse of spin-lattice relaxation time divided by temperature, (T1T)−1, for 7Li atom in D3LiIr2O6 and H3LiIr2O623. A broad hump of (T1T)-1 is seen at ~230 K for D3LiIr2O6, which is higher than ~180 K for H3LiIr2O6, suggesting the enhanced antiferromagnetic interactions. d Temperature dependence of (T1T)−1 for 2D. The (T1T)-1 data of 1H in H3LiIr2O623 are shown for comparison. Magnetic fields are applied parallel to the honeycomb plane of the field-oriented powder samples.

A more significant isotope effect was found in (T1T)-1 of 2D/1H (Fig. 3d). Each D(H) atom is connected to an oxygen atom forming an Ir-O2-Ir plaquette. (T1T)-1 of D(H) should be, therefore, sensitive to the nearest neighbor Ir-Ir magnetic correlation. In H3LiIr2O6, (T1T)-1 of 1H shows a monotonic increase below 100 K, unlike that of 7Li, implying a much weaker antiferromagnetic or possibly ferromagnetic correlation between the nearest Ir atoms23. In contrast, (T1T)-1 of 2D in D3LiIr2O6 exhibits a decrease with lowering temperature below 150 K and shows a dip at ~50 K as in 7Li, suggestive of the appreciable nearest neighbor antiferromagnetic correlations, which may consistently reflect the enhanced antiferromagnetic interactions in D3LiIr2O6. We note here that the positions of H/D atoms are slightly different in H(D)3LiIr2O6 (Fig. 1c), which could influence the hyperfine field at the H/D site and make the contrast more pronounced.

Spin-liquid behavior of D3LiIr2O6

Despite the gigantic isotope effect on the magnetic interactions between the Jeff = 1/2 moments, the ground state of D3LiIr2O6 was found to be a QSL as in H3LiIr2O6. On cooling further below the hump temperature, χ(T) in Fig. 2a shows a Curie-like upturn at low temperatures below 20 K. There was no signature of magnetic order or spin-glass freezing down to 2 K. No magnetic order was observed in specific heat C(T) down to 50 mK either, as displayed in Fig. 2d. The absence of magnetic order/spin-glass freezing is corroborated by the NMR measurements. Figure 3a, b show the 7Li and 2D-NMR spectra down to 2 K, respectively. Both spectra remain sharp without showing any splits or appreciable broadening on cooling, excluding the appearance of magnetic order or a spin-glass state. These results indicate that the QSL state is robust against the large modification of magnetic couplings owing to the H/D isotope effect.

K(T) is nearly temperature-independent below 60 K, as seen in Fig. 2c, indicating that the low-temperature upturn of χ(T) originates predominantly from magnetic impurities or defects. We note that the finite K(0) does not necessarily indicate gapless excitations in the presence of strong spin-orbit coupling and Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction34,35. The analysis of low-temperature specific heat C(T) for H3LiIr2O6 provides a strong indication of the existence of a magnetic excitation gap23.

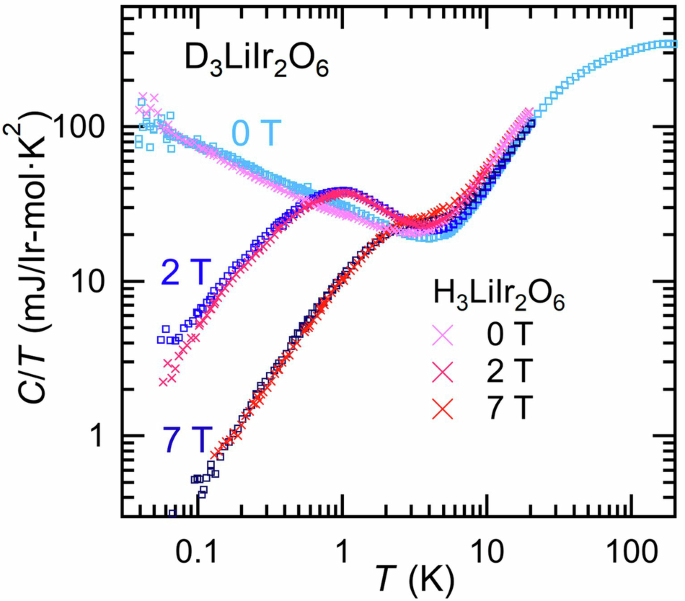

The low-temperature specific heat C(T, B) with and without applying magnetic field for D3LiIr2O6 shows strikingly similar behavior to those of H3LiIr2O6 as shown in Fig. 4. It is hard to distinguish the data for the two materials, in contrast to the gigantic H/D isotope effect on K(T) and χ(T). At zero magnetic field, C(T)/T displays a weak power-law increase C/T ∝ T-1/2, which points to abundant low-energy excitations. By application of magnetic fields, C(T)/T at low temperatures is strongly reduced, suggesting an opening of a gap. The C(T, B) of H3LiIr2O6 at low temperatures was found to follow the B/T scaling behavior, B1/2 C(T)/T = F(T/B)23, which should hold for that of D3LiIr2O6 as well. After the subtraction of the scaled contributions, C(T) of H3LiIr2O6 shows almost field-independent T3-behavior, which likely originates from the lattice, indicative of the absence of low-energy magnetic excitations and thereby a sizeable excitation gap23. The analogous C(T) behavior of D3LiIr2O6, regardless of distinct magnetic exchange parameters, supports that the low-temperature C(T, B) is dominated by spin defects of ~1% isolated from the QSL background and the magnetic contribution to C(T) from the bulk spin-liquid state is negligibly small below ~5 K. This also suggests that D3LiIr2O6 and H3LiIr2O6 share the similar disorder despite the contrast of OD and OH bonds. The low-temperature C(T, B) of H3LiIr2O6 has been argued to be in line with those of Kitaev spin liquid with bond-disorder or spin vacancies36,37,38,39.

Low-temperature specific heat C(T, B)/T of D3LiIr2O6 under magnetic fields B of 0, 2, and 7 T. The data for H3LiIr2O6 are also shown23. The low-temperature C(T)/T is strongly suppressed by B in both D3LiIr2O6 and H3LiIr2O6, indicating a similar form of low-lying excitations.

Discussion

The gigantic isotope effect on magnetic couplings is clearly linked to that on the O-D(H)-O interlayer structural unit. The formation of a covalent O-D(H) bond, unique to D(H)3LiIr2O6 among the honeycomb iridates, shall reduce the Ir 5 d-O 2p hybridization and hence suppress the super-exchange coupling between the Jeff = 1/2 moments40. If the magnetic exchange coupling is dominated by the d–p–d hopping processes, the distinct character of OD and OH bonds (Fig. 1c) naturally accounts for the giant isotope effect on the magnetic interaction. The theoretical calculations incorporating the effect of OD(OH) bonds indeed support the impact of OD(OH) bonds on magnetic couplings40,41,42 as well as the large difference between the OD and OH bonds40. We argue that this is firm evidence that the super-exchange process through oxygen is dominant in the interaction of Jeff = 1/2 moments of honeycomb iridates, which is a necessary condition but not a sufficient condition to realize the Kitaev model.

D3LiIr2O6 and H3LiIr2O6 are distinct from the other honeycomb Jeff = 1/2 magnets in that the ground state is a QSL instead of a magnetically ordered state. The early theoretical estimate of interaction parameters predicted that Kiteav interaction becomes largest when the Ir-O-Ir bond angle is ~100°43,44. However, the estimated magnetic exchange parameters for H3LiIr2O6 seem to be away from the very narrow region of the spin-liquid phase located near the pure Kitaev limit in the framework of the extended Kitaev model, including Heisenberg, off-diagonal, and further-neighbor interactions18,40,41,42,45. Considering the large difference in the exchange parameters between D3LiIr2O6 and H3LiIr2O6 due to the gigantic isotope effect, it is highly unlikely that the parameters for both D3LiIr2O6 and H3LiIr2O6 fall into the narrow parameter region for the QSL state. Additional ingredient(s) must be incorporated to stabilize the QSL state in these two compounds.

The disorder effect associated with OD bonds should be one of the important ingredients for the suppression of long-range magnetic order and the realization of the QSL state. Within the experimental resolution, the D+ ions fully substitute the interlayer Li+ ions of the parent α-Li2IrO3, and no signature of Li-D inter-site mixing was identified in the honeycomb layers. The dominant source of disorder in D3LiIr2O6 should be the random distribution of OD bonds. If we have a mixture of four different configurations of Ir-O2-Ir edge-shared bonds, namely Ir-O(OD)-Ir, Ir-(OD)O-Ir, Ir-O2-Ir and Ir-(OD)2-Ir, we expect to have essentially three different kinds of exchange paths, which distribute randomly and give rise to strong bond-disorder in the magnetic interactions. The random distribution of OD bonds above and below a honeycomb layer gives rise to disorder in the local crystal field acting on the Ir site and, hence, site-disorder as well.

How can such bond- and site-disorder lead to the QSL state in D3LiIr2O6? The theoretical studies pointed out that the Kitaev spin liquid is robust against the presence of disorders such as spin vacancies and bond-disorder40,41,42,46. However, this does not mean that disorder stabilizes the Kitaev spin-liquid state, and competing long-range orders that mask the spin-liquid state in other Kitaev materials need to be evaded. The appearance of a spin-liquid-like state by suppressing long-range order with the disorder has been discussed in geometrically frustrated systems47,48,49. It is conceivable that bond/site-disorder associated with OD bonds destabilizes competing long-range ordering in D3LiIr2O6. The disorder of OD bonds modulates not only the Kitaev exchange but also affects non-Kitaev interactions that would stabilize a long-range order, such as off-diagonal Γ coupling and particularly the Heisenberg coupling; when the two Ir-O-Ir super-exchange paths are asymmetric in the Ir-O(OD)-Ir bond, the destructive interference in the super-exchange paths is invalidated, and the sizeable Heisenberg coupling may be restored40. It is tempting to infer that such disordered non-Kitaev interactions destabilize competing magnetic orders while the emergent spin-liquid state is robust against the bond-disordered Kitaev interactions. The recent RIXS study on H3LiIr2O6 showed momentum-independent magnetic continuum excitations, supportive of a spin-liquid state associated with Kitaev-type coupling50. We, therefore, argue that the bond-disorder and frustrated Kitaev coupling concertedly play a role in realizing the spin-liquid state. Indeed, the theoretical Kitaev-Heisenberg model, including long-range interactions, indicates that the phase range of Kitaev spin liquid is extended in the presence of bond-disorder51.

For H3LiIr2O6, if H+ ions are fluctuating between the two off-center positions due to the quantum tunneling effect, all the Ir-Ir bonds would be regarded as identical, and no bond- or site-disorder would be present. However, the time scale of H+ motions was reported to be much slower compared to that of magnetic exchange52, and H+ ions should be considered static in the magnetic exchange process. In addition, strong stacking faults of the honeycomb layers may trap and localize part of H+ ions. Analogous bond/site-disorder should be present in H3LiIr2O6 as well.

To conclude, the deuterium-substituted honeycomb iridate D3LiIr2O6 realizes a quantum liquid state of spin-orbit-entangled Jeff = 1/2 pseudospin as in H3LiIr2O6. The isotope exchange from hydrogen to deuterium induces a pronounced structural modification of the O-D(H)-O interlayer unit and results in the drastic change of magnetic interactions through the super-exchange process involving O 2p state. Nevertheless, the QSL ground state is robust against the isotope effect. We argue that the disorder of OD (or OH) bonds, incorporated in a frustrated Kitaev material, plays a key role in realizing the quantum liquid state. We also expect that the variant super-exchange interactions associated with OH(D) bonds, as well as the bond/site-disorder effect, may be exploited to realize exotic magnetic ground states not only in Kitaev materials but in a wide variety of magnets53,54.

Methods

Sample synthesis and characterizations

Powder sample of D3LiIr2O6 was prepared by an ion-exchange reaction on α-Li2IrO3. The powder of α-Li2IrO3 was sealed in a Teflon-lined autoclave together with 4 M D2SO4 solution diluted by D2O, and heated at 125 °C for 120 h. The obtained powder was rinsed with D2O and dried in air. For the neutron diffraction study, α–7Li2193IrO3 was synthesized from 7Li2CO3 and metallic 193Ir, and the ion-exchange reaction was conducted on it. Transport, magnetic, and thermodynamic properties above 0.4 K were measured on a cold-pressed pellet by commercial apparatus (Quantum Design, MPMS-XL, and PPMS). The heat capacity measurement was performed by a relaxation method.

Powder X-ray diffraction

The crystal structure of the product was analyzed by powder X-ray diffraction. The diffraction patterns were collected at room temperature with Bruker D2 Phaser with Cu-Kα radiation. The detailed measurement shown in Fig. S1 was performed by using a Stoe Stadi-P transmission diffractometer (primary beam Johann-type Ge (111) monochromator for Ag-Kα1 radiation (λ = 0.55941 Å), Mythen-Dectris PSD with 12° 2θ opening) with the sample sealed in a glass capillary of 0.5 mm diameter (Hilgenberg, glass No. 50). The sample was spun during measurement for better particle statistics in both cases.

Neutron diffraction

The powder neutron diffraction measurement was performed at room temperature on the HRPD beamline at the ISIS Neutron and Muon Source. The powder was contained in a 6 mm diameter cylindrical vanadium can with data being collected using the 10–110 ms time-of-flight window. Isotope-enriched powder samples of D37Li193Ir2O6 and H37Li193Ir2O6 were prepared for neutron diffraction to reduce the absorption of neutrons to allow the refinement of fine structural details. The Rietveld refinement of crystal structure was performed using the GSAS-II software55. The crystal structure is visualized by using VESTA software56.

Low-temperature specific heat measurement

Specific heat C between 0.05 and 1 K was measured by using a cell installed in a dilution refrigerator57. The sample was wrapped by an annealed silver foil (residual resistivity ratio, RRR > 1000) and fixed by silver paste to ensure enough thermal link between the sample and the sample stage. A commercial setup (Quantum Design PPMS) was used above 0.4 K. The data was analyzed by the relaxation method. The subtraction of nuclear Schottky contributions was performed with the procedure described in ref. 23.

NMR measurements

NMR measurements were carried out with a standard coherent pulse spectrometer, cryo-cooled preamplifier, double-rotation probe, and 3He-circulation lines. The NMR frequency-swept spectra were acquired using a Fourier-step-sum technique, where each Fourier-transformed spectrum shifted with its center frequency are accumulated during the sweep. The quadrupole splitting for 7Li nuclei (I = 3/2) was very small, less than 20 kHz, throughout the experiment. The spin-lattice relaxation rate 1/T1 for 7Li was measured by a comb-shaped pulse recovery method with an empirical stretched-exponential recovery function, 1 − exp{−(t/ T1)β}, while that for 2D (I = 1) was obtained with the formula, 1 − {0.75exp(−(3t/T1)β) + 0.25exp(−(t/T1)β)}. The field-oriented samples were used for the measurements23.

Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering

(RIXS): The RIXS experiment at the Ir L3-edge was performed at BL11XU of SPring-8. The energy of incident X-rays was tuned at 11.214 keV, which is about 3 eV below the peak energy of the white line in the X-ray absorption spectrum at the Ir L3-edge. This energy corresponds to the excitation of Ir 2p3/2 to 5d t2g. The incident X-ray beam was monochromatised by a double-crystal Si(111) monochromator and a secondary Si(844) four-crystal monochromator. The scattered X-rays were analyzed by a diced and spherically bent Si(844) crystal. The scattering angle was kept at 90 degrees, and π-polarized incident X-rays were used to minimize the elastic scattering. The measurement was performed at 10 K, and the total energy resolution was about 50 meV. The cold-pressed pellets of D(H)3LiIr2O6 powder were used for the measurement. The spectrum of α-Li2IrO3 sintered pellet was also measured for comparison. The obtained spectra can be regarded as a q-averaged one. Since the d–d excitations do not show sizable q-dependence31, the spectra should reflect the essential features of d–d excitations. Further discussions about the RIXS spectra are given in Supplementary information, which includes refs. 58,59,60.

Responses