ROS-ATM-CHK2 axis stabilizes HIF-1α and promotes tumor angiogenesis in hypoxic microenvironment

Introduction

Multicellular organisms have developed complex stress mechanisms to sense and regulate oxygen concentrations and make adaptive changes to maintain the homeostasis of cells and tissues. Stress responses protect against pathologic hypoxia to avoid ischemic tissue damage and the development of certain diseases [1,2,3,4]. In the early stage of tumorigenesis, oxygen supplied by the blood vessels gradually fails to meet metabolic demands, which induces hypoxia, leading to cell apoptosis or necrosis. However, hypoxia caused by hypoperfusion stimulates the expression of genes that confer hypoxia tolerance in surviving tumor cells [5, 6]. It enables tumor cells to adapt to a hypoxic state and facilitates disruption of the equilibrium between pro- and antiangiogenic factors [7], stimulating angiogenesis in tumor tissues.

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) is a transcription factor characterized by a basic helix-loop-helix/Per-Arnt-Sim domain, which plays a key role in regulating cellular responses to oxygen deprivation and acts as a crucial driver in tumor angiogenesis [8]. The von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor protein recognizes cytoplasmic HIF-1α under normal oxygen concentrations because prolyl hydroxylase domain proteins (PHDs) 1–3 rapidly hydroxylate it at proline residues 402 and 564 [9, 10]. This recognition results in the recruitment of a ubiquitin-protein ligase complex, which in turn induces the ubiquitination and degradation of HIF-1α by the 26S proteasome, thereby reducing the half-life of HIF-1α in the presence of oxygen [11]. Nevertheless, PHDs are inactive under hypoxic conditions, emerging in reduced hydroxylation and degradation of HIF-1α. Subsequently, cytoplasmic HIF-1α translocate in the nucleus, where it binds to hypoxia-responsive elements of multiple target genes linked to angiogenesis, proliferation, and other related pathways [12].

Hypoxia is a familiar characteristic of solid cancers and one of the driving factors of genomic instability. It triggers DNA replication stress and even DNA damage, thereby resulting in the activation of DNA damage repair (DDR) responses. DDR-related molecules participate in regulation of HIF-1α expression [13,14,15]. For example, the tumor suppressor protein breast cancer 1 (BRCA1) is involved in the homologous recombination repair of DDR and regulates the transcription of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) through interactions with HIF-1α [13]. A crucial role in mitosis, chromosomal stability, and cell fate is played by checkpoint kinase 2 (CHK2), a crucial molecule in the DDR pathway. To date, 24 substrates of human CHK2 have been identified, including BRCA1 and E2F transcription factor 1 (E2F1), among others [16,17,18,19,20,21]. DDR in the same tumor tissue is more effective under hypoxic conditions compared to non-hypoxic ones due to the activation of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM)/checkpoint kinase 1 (CHK1)/CHK2 DDR pathway [22]. It has been demonstrated that p53-mediated apoptosis is initiated by oxalomalate, an intermediate of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, via ATM-CHK2 signaling dependent on reactive oxygen species (ROS). Furthermore, it promotes the ROS-dependent E2F1-mediated degradation of HIF-1α, which decreases VEGF expression [23]. However, no evidence supports a direct regulatory relationship between HIF-1α and CHK2.

Therefore, this study aimed to clarify the main molecular mechanism underlying HIF-1α regulation in the hypoxic tumor microenvironment to deliver a theoretical basis for developing anti-angiogenesis therapies and identifying potential therapeutic targets. The results showed that CHK2 is a key mediator of tumor angiogenesis, whereby HIF-1α is phosphorylated by a formerly uncharacterized direct phosphorylation event that dislocates HIF-1α ubiquitination and degradation without the need for hydroxylation-induced activation of the Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor pathway.

Results

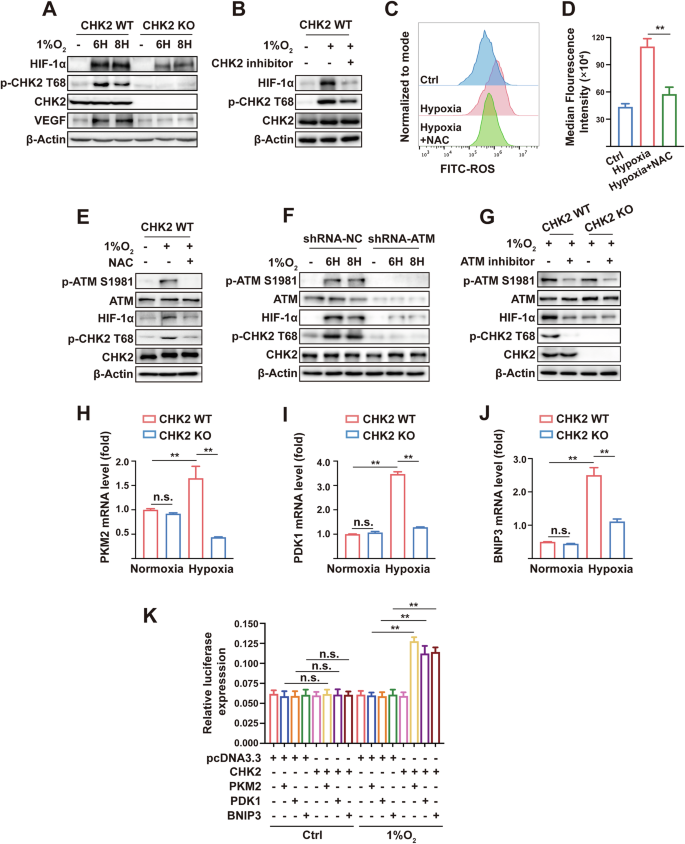

HIF-1α is sustained under hypoxic conditions by phosphorylated CHK2

To evaluate the regulatory relationship between CHK2 and HIF-1α, we seeded HEK293-WT and HEK293-CHK2-KO cells under a hypoxic environment (1% O2) for 6 h and 8 h. Next, we used western blot analysis to show that p-CHK2 (Thr68) was significantly activated in HEK293-WT cells under hypoxic conditions, accompanied by up-regulation of HIF-1α and its down-stream target VEGF (Fig. 1A). However, in HEK293-CHK2-KO cells, hypoxic conditions did not increase HIF-1α or VEGF expression levels (Fig. 1A). In addition, the CHK2 inhibitor reversed the increased expression of HIF-1α triggered by hypoxia (Fig. 1B), suggesting that hypoxia promotes up-regulation of HIF-1α via p-CHK2 (Thr68). As reported, hypoxic conditions may induce excessive production of ROS by cells and trigger oxidative stress. NAC, a scavenger of free radicals, was used to determine whether ROS acts to transduce signals in hypoxia-induced regulatory responses. It is elucidated that hypoxia was correlated with an increase in ROS production, while the administration of NAC counteracted this increase in ROS generation in H1299 cells (Fig. 1C, D). Furthermore, the outcomes of western blot analysis demonstrated that the addition of NAC eliminated the increased expression of HIF-1α brought by hypoxia through inhibiting phosphorylation of CHK2 (Fig. 1E), demonstrating that ROS-induced perturbations transmitted hypoxia signals through the CHK2/HIF-1α pathway to activate hypoxia-tolerant regulation. Oxidative stress is frequently followed by CHK2 (Thr68) phosphorylation through ATM stimulation, signifying that ATM is a significant sensor of ROS in human cells [24]. Moreover, hypoxia failed to phosphorylate CHK2 (Thr68), resulting in low expression of HIF-1α in ATM shRNA-treated cells (Fig. 1F). Similar results were observed with cells under hypoxic conditions by adding the ATM inhibitor (Fig. 1G), suggesting that hypoxia promotes up-regulation of HIF-1α through the ATM/CHK2 pathway. The results of RT-qPCR (Fig. 1H–J) and dual-luciferase reporter gene experiment (Fig. 1K) demonstrated that CHK2 augmented hypoxia signaling via enhancing HIF-1α-dependent transcriptional activity in a hypoxic condition. Consequently, these findings propose that hypoxia enhances HIF-1α expression by activating the ATM/CHK2 pathway via ROS transmission, thereby augmenting hypoxia signaling.

A Western blotting of HIF-1α, p-CHK2 Thr68, CHK2, VEGF. For all Western blotting, β-actin was used as a loading control. 1% O2 was performed in HEK293 cells and HEK293-CHK2-KO cells for indicated times. B Western blotting of HIF-1α, p-CHK2 Thr68 and CHK2. HEK293 cells were stimulated by 1% O2, CHK2 inhibitor and combination for 6 h. C, D Flow cytometric analysis of ROS levels and median fluorescence intensity of ROS expression. H1299 cells were stimulated by 1% O2 with or without NAC for 6 h. **p < 0.01. E Western blotting of p-ATM S1981, ATM, HIF-1α, p-CHK2 Thr68 and CHK2. HEK293 cells were pretreated with NAC for 4 h and then cultured in 1% O2 for 6 h. F Western blotting of p-ATM S1981, ATM, HIF-1α, p-CHK2 Thr68 and CHK2. H1299 cells were transfected with the indicated shRNA and exposed to 1% O2 for indicated times. G Western blotting of p-ATM S1981, ATM, HIF-1α, p-CHK2 Thr68 and CHK2. HEK293 and HEK293-CHK2-KO cells were exposed to 1% O2 or combination with ATM inhibitor for 6 h. RT-qPCR analysis of PKM2 (H), PDK1 (I) and BNIP3 (J) mRNA in CHK2-deficient or wildtype HEK293 cells treated with or without hypoxia for 6 h. **p < 0.01, n.s. not significant. K Dual-luciferase reporter gene experiment of PKM2, PDK1 and BNIP3. HEK293-CHK2-KO cells were co-transfected with reporter gene and CHK2 plasmid under normoxia (21% O2) and hypoxia (1% O2). **p < 0.01, n.s. not significant.

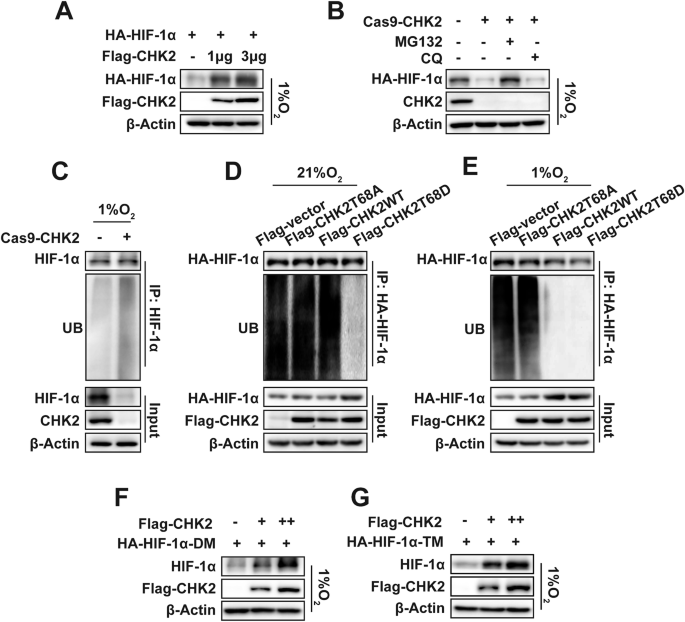

CHK2 stabilizes HIF-1α by blocking ubiquitination of HIF-1α

The main mechanism employed by CHK2 to sustain HIF-1α concentrations during a hypoxic state was further investigated. Ectopic CHK2 expression in H1299 cells led to a dose-dependent increase in co-transfected HIF-1α protein levels (Fig. 2A). The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) is the main regulator of the stability and degradation of HIF-1α. This study showed that CHK2 significantly reduces HIF-1α degradation under hypoxic conditions through the proteasomal pathway. KO of CHK2 significantly reduced HIF-1α protein concentrations under hypoxic conditions, and this effect was maintained when the cells were treated with the specific proteasome inhibitor MG132 but not with the lysosome inhibitor chloroquine (Fig. 2B). The results of the Co-IP analysis confirmed that ubiquitination of HIF-1α was increased in CHK2-KO HEK293 cells compared to WT HEK293 cells under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 2C). Under normoxic and hypoxic conditions, mimicking phosphorylation of Thr68 with a negatively charged amino acid, Asp (T68D), inhibited CHK2 ubiquitination, while the CHK2 T68A mutant did not (Fig. 2D, E). We verified the hypothesis that CHK2 might regulate hydroxylation-dependent proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α because proline hydroxylation is a chief regulator of HIF-1α protein concentrations. However, increased concentrations of a double mutant HIF-1α protein with Pro → Ala mutations at both hydroxylation sites (P402A/P564A) were brought about by CHK2 overexpression (Fig. 2F). The same outcome was observed with a triple mutant HIF-1α protein (P402A/P564A/N803A) (Fig. 2G). Of note, after treatment with the proline hydroxylase inhibitor FG4592 at extended periods (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A, B) and increased concentrations (SI Appendix, Fig. S1C, D), endogenous HIF-1α protein levels were lower in CHK2-KO HEK293 cells than WT HEK293 cells. These results indicate that irrespective of HIF-1α proline hydroxylation, CHK2 stabilizes HIF-1α by blocking the UPS degradation pathway.

A Western blotting of exogenous HA-HIF-1α and Flag-tagged CHK2. HA-tagged HIF-1α (3 μg) and Flag-tagged CHK2 (1 μg, 3 μg) was transiently transfected into H1299 cells and then exposed to 1% O2. B Western blotting of exogenous HA-HIF-1α and CHK2. HA-tagged HIF-1α was transiently transfected into HEK293 and HEK293-CHK2-KO cells under hypoxic microenvironment. MG132 and CQ was then added to above cells respectively or together as indicated. C Endogenous HIF-1α ubiquitination in HEK293 and HEK293-CHK2-KO cells under hypoxia (1% O2) for 6 h. Exogenous HA-HIF-1α ubiquitination under normoxia (D) and hypoxia (E) in HEK293-CHK2-KO cells transiently transfected with indicated plasmids. F Western blotting of exogenous double mutant HIF-1α protein at both hydroxylation sites P402A/P564A (HA-HIF-1α-DM). HEK293 cells were transfected with an increasing amount of Flag-CHK2 expression plasmid and exposed to hypoxia. G Western blotting of exogenous triple mutant HIF-1α protein at P402A/P564A/N803A (HA-HIF-1α-TM). HEK293 cells were transfected with an increasing amount of Flag-CHK2 expression plasmid and exposed to hypoxia.

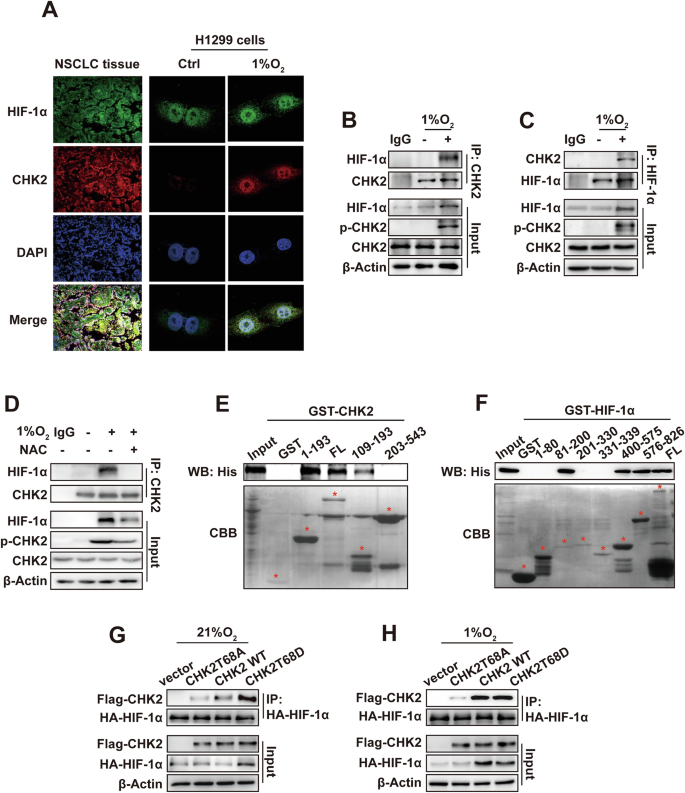

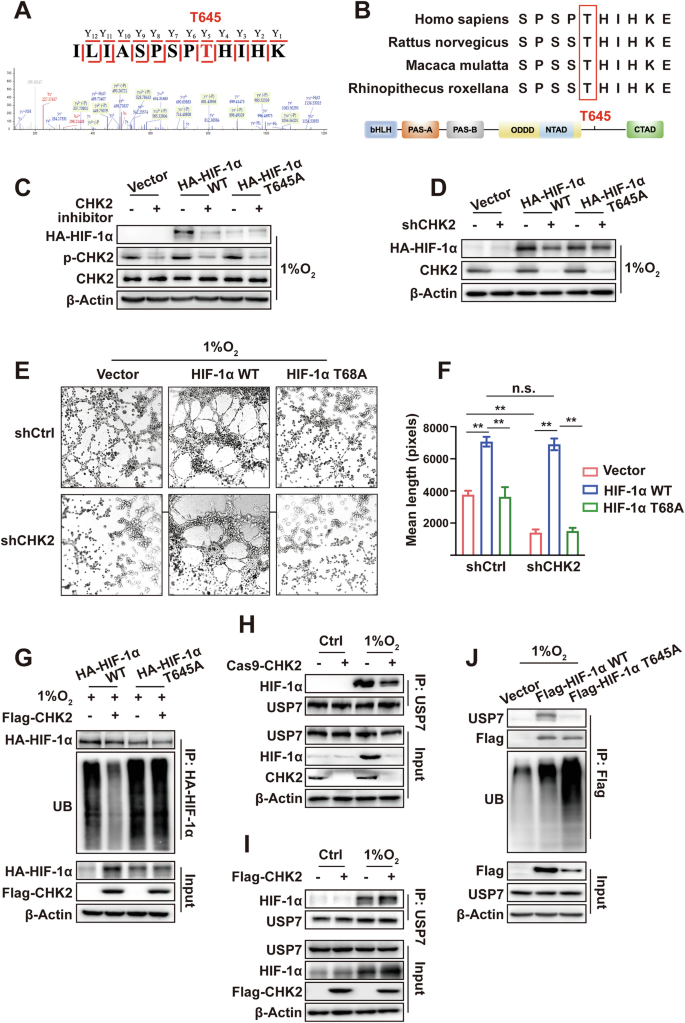

Hypoxia prompts CHK2-induced phosphorylation of HIF-1α at Thr645

The serine/threonine kinase CHK2 substrates include proteins related to the DDR and cell cycle and transcription factors, such as p53 and E2F-1 [25]. Whether CHK2 curbs UPS degradation (phosphorylation) of HIF-1α, a pivotal transcription factor in hypoxia signaling remains unclear. The immunofluorescence of NSCLC tissues elucidated the colocalization of CHK2 and HIF-1α in tumor tissue (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the confocal microscopy results found that hypoxia promoted colocalization of endogenous CHK2 and HIF-1α in nuclei of H1299 cells (Fig. 3A). Next, the Co-IP assay confirmed that hypoxic conditions enhanced the interactions between CHK2 and HIF-1α in H1299 cells (Fig. 3B, C) and HEK293 cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A, B). However, NAC inhibited complex formation between CHK2 and HIF-1α triggered by hypoxia via prohibiting CHK2 phosphorylation in H1299 cells (Fig. 3D). The study used both full-length and truncated forms of CHK2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) to identify the specific sections of CHK2 responsible for interacting with HIF-1α. The results showed that the forkhead-associated domain (residues 115–175) of CHK2 was adequate to bind HIF-1α (Fig. 3E). Domain mapping indicated that the Per-Arnt-Sim-A domain (residues 81–200), oxygen-dependent degradation domain (residues 400–575) and inhibitory domain-C terminal transactivate on the domain (residues 576–826) of HIF-1α (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B) could directly interact with CHK2 (Fig. 3F). Moreover, we detected CHK2 phosphorylation at Thr68 under hypoxic conditions, which promoted interactions with HIF-1α. Under both normoxic and hypoxic conditions, Imitating Thr68 phosphorylation with Asp (T68D), a negatively charged amino acid, endorsed relationships between CHK2 and HIF-1α (Fig. 3G, H). Consistent with the above hypothesis, the formation of a WT CHK2 and HIF-1α complex was observed under hypoxic conditions, while mutant CHK2 (T68A) did not form a complex (Fig. 3H). Next, in vitro CHK2 kinase assay was performed using recombinant CHK2 and HIF-1α (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Then, phosphorylation site mass spectrometry analysis according to in vitro CHK2 kinase assay was conducted, which detected that CHK2 could phosphorylate HIF-1α at Ser641, Ser643, and Thr645 (Fig. 4A). Among these, Ser641 and Ser643 are purportedly target sites of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), involved in HIF-1α transcriptional activity and nuclear buildup, but not stability. Thr645 is a formerly uncharacterized site positioned within the inhibitory domain of HIF-1α, which inhibits transcriptional activity of the trans-activating domains under normoxic conditions [26]. Thr645 is evolutionarily preserved among mammals (Fig. 4B), signifying its importance as a regulatory site. To further evaluate the Thr645 phosphorylation effect on the stability of the HIF-1α protein, site-directed mutagenesis was used to produce HIF-1α T645A (phospho-null) constructs. The CHK2 inhibitor and CHK2 shRNA treatment prohibited WT HIF-1α’s stability under hypoxic conditions. It is demonstrated that expression of the mutant HIF-1α (T645A) was relatively lowered under hypoxic conditions and not regulated by phosphorylation of CHK2 (Fig. 4C, D). Meanwhile, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) tube formation assay was conducted to verify that WT HIF-1α transfection counteracted the inhibition of tube formation induced by CHK2 shRNA treatment under hypoxia condition, however, the mutant HIF-1α (T645A) transfection failed (Fig. 4E, F). Consistently, transfection of Flag-CHK2 in CHK2-KO HEK293 cells enhanced protein expression of WT HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions by reducing ubiquitination of HIF-1α (Fig. 4G). While transfection of Flag-CHK2 failed to increase the stability of mutant HIF-1α (T645A) due to persistently high ubiquitination levels (Fig. 4G). These findings strongly suggested that CHK2 might phosphorylate HIF-1α at Thr645 to improve protein stability by reducing UPS degradation under hypoxic conditions.

A Colocalization of CHK2 and HIF-1α shown by representative confocal microscopic images of NSCLC tissues and H1299 cells. For H1299 cells, experiments were conducted under normoxia (21% O2) and hypoxia (1% O2), respectively. B, C. Co-IP of endogenous CHK2 with HIF-1α in H1299 cells under normoxia (21% O2) and hypoxia (1% O2). IgG, immunoglobulin G. D Co-IP of endogenous CHK2 with HIF-1α in H1299 cells pretreated with NAC for 4 h and then cultured in 1% O2 for 6 h. E GST-pull-down assay of His-HIF-1α fusion proteins with bacterially expressed GST-CHK2 fragments. Coomassie Brilliant Blue (CBB) staining shows expression of GST and GST-CHK2 fragments. F GST-pull-down assay of His-CHK2 fusion proteins with bacterially expressed GST-HIF-1α fragments. CBB staining shows expression of GST and GST-HIF-1α fragments. G, H Co-IP of exogenous HA-HIF-1α with Flag-CHK2 under normoxia (21% O2) and hypoxia (1% O2) in HEK293-CHK2-KO cells transiently transfected with indicated plasmids.

A Mass spectrogram of phosphorylation sites of HIF-1α protein T645. B Sequence alignment surrounding the T645 residue of HIF-1α homologs in various species. C Western blotting of HA-HIF-1α, p-CHK2 and CHK2. CHK2 inhibitor was added to HEK2923 cells transiently transfected with plasmids as indicated under hypoxia (1% O2). D Western blotting of HA-HIF-1α and CHK2. shCHK2, HA-HIF-1α and HA-HIF-1α Thr645A plasmids was transiently transfected into HEK293 cells as indicated under hypoxia (1% O2). E Representative images of HUVEC tube formation assay after 24 h incubation in the indicated conditioned media from H1299 cells. F Mean tube length in E was quantified. **p < 0.01, n.s. not significant. G Exogenous HA-HIF-1α ubiquitination was detected by Co-IP. Flag-CHK2, HA-HIF-1α and HA-HIF-1α Thr645A plasmids were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells as indicated under hypoxia (1% O2). H Co-IP of endogenous HIF-1α with USP7 in HEK293 cells and HEK293-CHK2-KO cells under normoxia (21% O2) and hypoxia (1% O2). I Co-IP of endogenous HIF-1α with USP7. Flag-CHK2 plasmids was transiently transfected into HEK293 cells as indicated under normoxia (21% O2) and hypoxia (1% O2). J Ubiquitination of Flag-HIF-1α WT and Flag-HIF-1α T645A. Flag-HIF-1α and Flag-HIF-1α Thr645A plasmids were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells as indicated under hypoxia (1% O2).

CHK2-induced phosphorylation of HIF-1α increases HIF-1α stability by promoting complex formation with USP7

As reported, a key regulator of HIF-1α‘s ubiquitination and degradation is the von Hippel–Lindau E 3 ligase complex. However, some ubiquitin-specific proteases can shear the conjugated ubiquitin chains from HIF-1α into free ubiquitin, thus reversing the regulatory effect of ubiquitination modification on HIF-1α protein stability [27]. USP7, a deubiquitinating enzyme that acts on HIF-1α, mainly plays a regulatory role in the deubiquitination of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions by mediating epithelial-mesenchymal transformation, tumor invasion, and metastasis in NSCLC [28]. CHK2 KO weakened the complex formation of HIF-1α and USP7 (Fig. 4H), while CHK2 overexpression promoted the binding of USP7 and HIF-1α (Fig. 4I). However, these changes were not detected under normoxic conditions due to the absence of p-CHK2 (Fig. 4H, I). In addition, HIF-1α phosphorylation at Thr645 is necessary for the HIF-1α/USP7 complex to form under hypoxic conditions. When mutated to Thr645A, the binding intensity of HIF-1α and USP7 was significantly weakened, leading to more ubiquitination of HIF-1α (Fig. 4J). Consequently, these data show that CHK2 promotes the binding of HIF-1α to the deubiquitinating enzyme USP7, which is dependent on the phosphorylation of HIF-1α at Thr645.

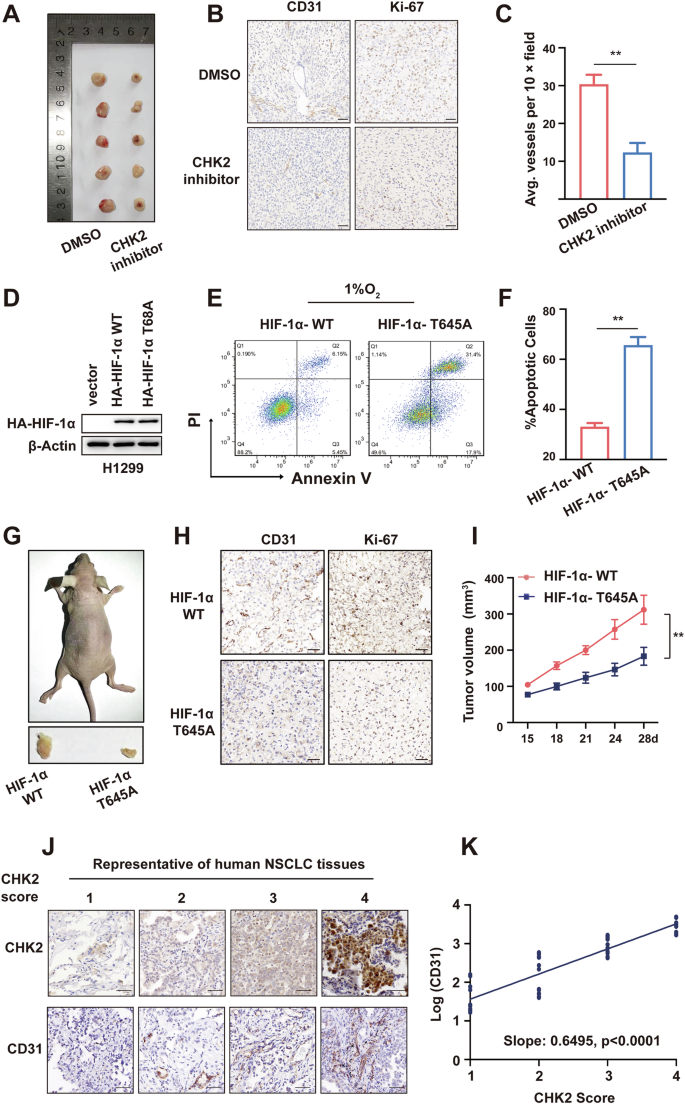

Mutation at HIF-1α Thr645 aggravates hypoxia-induced cell apoptosis and prohibits tumor proliferation and angiogenesis

Next, a CHK2 inhibitor was used to check if CHK2 is enough to endorse angiogenesis in vivo. Briefly, the flanks of 10 female nude (n = 5/group) were subcutaneously inoculated with 1 × 107 H1299 human NSCLC cells. DMSO or the CHK2 inhibitor (1 mg/ kg) was administered intraperitoneally on alternate days for 20 days. The results of IHC analysis revealed a significant decrease in CD31 expression (p < 0.01) in mice xenografts in the CHK2 inhibitor group (Fig. 5A–C), indicating that p-CHK2 inhibition prohibits tumor angiogenesis. Flow cytometry made it possible to determine the impact of hypoxia-induced Thr645 phosphorylation of HIF-1α on cell apoptosis. We first validated the HA-tagged protein expression in HIF-1α-WT and HIF-1α-T645A stable transduced H1299 cells by western blotting (Fig. 5D). The results of flow cytometry indicated that HIF-1α-T645A transduced H1299 cells were more susceptible to hypoxia-induced apoptosis than HIF-1α-WT transduced H1299 cells (Fig. 5E, F). Considering the significance of HIF-1α in the tumor microenvironment and on physiological processes critical for tumorigenesis, we aimed to check if HIF-1α-T645A was enough to cause tumor growth in vivo. To lessen inter-mouse variability, we injected six nude mice in either the right or left flank with H1299 cells expressing HIF-1α-WT or HIF-1α-T645A, respectively. IHC staining of Ki-67 and tumor volume curve revealed that the HIF-1α-T645A tumors had lower multiplication than HIF-1α-WT tumors (Fig. 5G–I). Additionally, the HIF-1α-T645A tumors revealed impaired angiogenesis, as shown by immunostaining for CD31 (Fig. 5H). Consequently, these findings propose that mutant HIF-1α (T645A) increases cell vulnerability in the hypoxic microenvironment and diminishes vascularity and cell proliferation in vivo. Furthermore, IHC analysis was performed to measure the expression concentrations of CHK2 and CD31 (a marker of endothelial cells) in 50 NSCLC tissue samples (Fig. 5J) attained from diagnostic cores of patients before treatment at Shengjing Hospital. A statistically significant relationship between microvessel density and CHK2 expression was found (Fig. 5K), indicating a potential role for CHK2 in vascularization during human tumor trials.

A Ten mice (n = 5/group) were injected with H1299 cells. DMSO or the CHK2 inhibitor (1 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally on alternate days for 20 days. B Representative CD31 and Ki-67 staining of harvested xenografts of mice treated by DMSO or CHK2 inhibitor. Scale bar = 50 μm. C Quantification of IHC. **p < 0.01. D Western blotting of HA-tagged protein in HIF-1α-WT and HIF-1α-T645A stable transduced H1299 cells. E, F Flow cytometry and statistical analysis showing cell apoptosis exposed to hypoxia of the H1299 cells with indicated transfection. **p < 0.01. G H1299 cells stably expressing HIF-1α WT or HIF-1α T645A were injected subcutaneously into the rear flanks of athymic nude mice (n = 6). H IHC of harvested tumors in G with antibodies specific for CD31 and Ki-67 to assess angiogenesis and proliferation respectively. I Measurement of tumor volume of mice in (G). **p < 0.01. J Representative CHK2 and CD31 staining in NSCLC tissues, n = 50. K Scattering plot depicting the correlation between CHK2 and CD31 score.

Discussion

A recent study reported that antiangiogenic therapy combined with chemotherapy improved the prognosis of patients with NSCLC [29]. Anti-angiogenic drugs inhibit neovascularization by targeting the VEGF pathway, resulting in relatively low perfusion of tumor tissues while inhibiting ischemic necrosis of tumor cells [30]. However, long-term hypoxia caused by limited blood supply results in adaptive responses of tumor cells and subsequent elevated resistance to antiangiogenic drugs [31].

HIF-1α could be the key driver of adaptive regulation in response to hypoxia, thus presenting a promising antiangiogenic target to regulate tumor growth by interfering with the responses of cancer cells to hypoxic conditions. It has been reported that the angiogenic gateway blockers benzophenone-1B, acriflavine, and topotecan interfere with HIF-1-α-mediated angiogenesis by blocking HIF-1α nuclear translocation and dimerization with β, HIF-1α/HIF-2α-mediated activation of VEGF, or HIF-1α mRNA translation [32]. It has been shown that there are no approved selective HIF-1α inhibitors for clinical usage, despite several studies.

To our knowledge, epigenetic therapy drugs alone do not usually have a significant anti-tumor effect but act as a ‘whetstone’ to make an already blunt anti-tumor weapon sharp again. This special ‘sharpening weapon’ possesses the potential to reverse resistance to anti-tumor drugs. Although successful therapeutic targeting of HIF-1α has proven challenging, targeting of HIF-1α post-translational modification might be plausible.

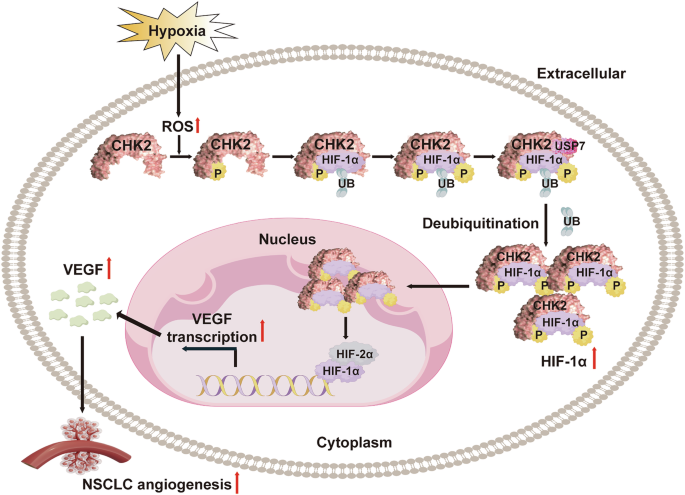

CHK2 expression showed a significant correlation with human tumor sample vascularization. Meanwhile, inhibition of CHK2 phosphorylation down-regulated HIF-1α and prohibited angiogenesis, as confirmed with a xenograft model, establishing a new mechanism of tumor progression promoted by CHK2 kinase (Fig. 6). Moreover, our findings suggest that hypoxia enhanced expression of HIF-1α by activation of the ATM/CHK2 pathway via ROS transmission, thus augmenting hypoxia signaling. A novel post-translational variation controlling proteasomal degradation of HIF-1α was identified. Theoretically, it is extremely possible that independent of proline hydroxylation, phosphorylating HIF-1α at Thr645 by CHK2 kinases might prevent ubiquitination and HIF-1α degradation by the 26S proteasome. Though we could not directly verify the phosphorylation of Thr645 by CHK2 using in vitro kinase assays due to strict management of 32P following the National Environmental Protection Agency, site-directed mutagenesis indirectly confirmed that Thr645 is the very phosphorylation site by CHK2.

Model showing CHK2 interaction with the HIF-1α inhibitory domain and phosphorylate HIF-1α at Thr645 site, enhancing HIF-1α binding to its deubiquitinating enzyme USP7, prohibiting HIF-1α ubiquitination and thus triggering angiogenesis by upregulating VEGF.

To date, three phosphorylation sites have been detected in the inhibitory domain of HIF-1α, namely Ser641, Ser643, and Ser668. Among these, Ser641 and Ser643 can be phosphorylated by MAPK, which enhances the intracellular accumulation and transcriptional activity of HIF-1α by preventing its nuclear translocation via the chromosomal maintenance 1-dependent pathway [33]. CDK1 can phosphorylate Ser668 to stabilize HIF-1α expression independent of changes in oxygen concentration [34]. However, phosphorylation of HIF-1α at Thr645 has not yet been confirmed. Hence, the regulatory relationship between HIF-1α Thr645 phosphorylation and UPS degradation remains unclear. This is the first study to strongly suggest that HIF-1α phosphorylation at Thr645 might improve protein stability of HIF-1α via reducing UPS degradation under hypoxic conditions, thereby offering novel insights into modified phosphorylation and ubiquitination of HIF-1α.

KO of CHK2 is a potential way to address hypoxia-mediated therapeutic resistance by simultaneously targeting hypoxic tumor cells and inhibiting HIF-1α phosphorylation and angiogenesis. Additionally, HIF-1α phosphorylation at Thr645 was found to be a promising biomarker of CHK2 inhibitor efficacy in human tumors, which contributes to clarifying the molecular-level roles of CHK2 inhibition in anti-angiogenesis.

Materials and methods

Cell line and culture conditions

We procured the HEK293 and H1299 cell lines from the Cell Resource Center (Chinese Academy of Science Committee, Shanghai, China). We employed 10% fetal bovine serum in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (HyClone Laboratories, Inc., South Logan, UT, USA) as a culture medium and kept it at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2/95% air. We replicated hypoxic conditions with a bis-gas incubator (1% O2, 5% CO2, balanced with N2). The source of cell lines were authenticated and tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Antibodies (Abs) and chemical reagents

We acquired antibodies against HIF-1α (20960-1-AP) from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL, USA). Antibodies against CHK2 (05-649) were purchased from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Antibodies targeting phosphorylated CHK2 (Thr68, #2661), ATM (#2873), p-ATM (Ser1981, #13050), VEGF-A (#50661), ubiquitin (#3933S), β-actin (#3700), human influenza hemagglutinin (HA)-tag (#2367) and His-tag (#2365) were sourced from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). The FLAG (DYKDDDDK)-tag antibodies (SG4110-16) were acquired from Shanghai Genomics Technology, Ltd. (Shanghai, China). N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), adenosine triphosphate, puromycin, and antibodies against ubiquitin-specific peptidase 7 (USP7) (SAB1307082) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Corporation (St. Louis, MO, USA). Protein A/G agarose was acquired from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Dallas, TX, USA). The CHK2 inhibitor II (S8632), ATM inhibitor (KU-55933) and the HIF-α prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor FG4592 (S1007) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals (Houston, TX, USA).

Plasmid constructs, mutagenesis, transfection and viral infection

We procured CHK2 and HIF-1α expression plasmids from Addgene, Inc. (Watertown, MA, USA) and GeneChem Inc. (Daejeon, South Korea). The pGEX-5X-1 vector was used to generate plasmids coding for His-CHK2 (WT), His-HIF-1α(WT), glutathione S-transferase (GST)-CHK2 (amino acids [aa] 1–193), GST-CHK2 (aa 109–543), GST-CHK2 (aa 203–543), GST-HIF-1α (aa 1–80), GST- HIF-1α (aa 81–200), GST- HIF-1α (aa 201–330), GST- HIF-1α (aa 331–399), GST- HIF-1α (aa 400–575), and GST- HIF-1α (aa 576–826). Mutagenesis (CHK2 T68A, CHK2 T68D, and HIF-1α T645A) was performed via the QuikChange™ Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA). All constructs were confirmed using DNA sequencing, and the plasmids were then transfected into cells using the jetPrime Transfection reagent (Polyplus PT-114-15).

Lentiviral small hairpin RNA (shRNA) against CHK2 (5′-ACAGATAAATACCGAACAT-3′) and ATM (5′-GGAGCCATTTATTGAAACT-3′), as well as a control, were purchased from Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Puromycin (2 g/ml) was added to the cell cultures to select for stable silencing and control cell lines.

Lentiviral vectors coding for HIF-1α WT (5E + 8 TU/ml) and HIF-1α T645A (1E + 9 TU/ml) were produced by Heyuan Biotechnology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The H1299 cells were incubated with the lentiviral vectors at a multiplicity of infection of 20–30 for 24 h, following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Puromycin was used to select for infected cells.

Immunofluorescence and confocal images

Cells were seeded on coverslips and fixed with a 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 15 minutes. They were then made permeable using a 0.1% Triton X-100 solution. The cells were treated with a blocking solution containing 5% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to prevent non-specific binding. The cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary Abs: rabbit anti-HIF-1α (dilution, 1:200) and mouse anti-CHK2 (dilution, 1:400; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; #17332). After a PBS wash, the coverslips were stained for 60 min using Alexa Fluor 594- and 630-conjugated secondary Abs (diluted at a ratio 1:400; Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Next, they were again washed with PBS, stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Sigma-Aldrich Corporation), and imaged using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Ti-E, DS-Ri2; Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a 60× oil objective lens.

Flow cytometry

We applied the Annexin VAPC/ 7-AAD kit (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech. Co. Ltd, Nanjing, China) to quantify the proportion of apoptotic cells cultured under hypoxic conditions for 96 h.

For ROS detection by flow cytometry, cells were pretreated with NAC for 4 h and then replace the culture medium. After that, cells were stimulated with 1% O2 with or without NAC for 6 h followed by incubation with FITC-ROS (MAK143, Sigma) at 37 °C for 45 min in the dark.

In vitro CHK2 kinase assay

Purified Flag-tagged HIF-1α protein was incubated with recombinant CHK2 (200 ng) in a kinase buffer [50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2,10 mM MnCl2, 0.2 mM DTT containing 100 μM ATP per reaction] for 45 min at 30 °C. SDS-PAGE was then performed to separate phosphorylated proteins. Phosphorylation site identification was further analyzed via mass spectrometry.

HUVEC tube formation assay

The growth factor-reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences, USA), pipette tips and 96-well plates were all prechilled at 4 °C overnight. 50 μl Matrigel was carefully dispensed into each well of the 96-well plate and then incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to allow the Matrigel to solidify and form a gel-like matrix. The harvested HUVEC cells were gently seeded onto the solidified Matrigel at 37 °C. The conditioned media harvested from H1299 cells was added into 96-well plates. After 6 h co-culture, the conditioned media was removed. The tube formation was observed under a phase-contrast microscope. The mean tube length was quantified by using Image J software.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis

We steered the IHC analysis to notice CHK2, Ki-67, and CD31 expression in tumor tissues. The nuclei were stained with hematoxylin (Fuzhou Maixin Biotech, Co., Ltd, Fuzhou, China). Sections of the tumor tissues were hydrated, clarified, sealed with neutral resin, and photographed.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) assay

Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used to reverse transcribe the extracted total RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA). We extracted the total RNA using RNAiso Plus total RNA extraction reagent (TaKaRa Bio, Inc., Shiga, Japan). The latter was amplified via RT-qPCR using MonAmp™ SYBR® Green qPCR Mix (High Rox) provided by Monad Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China.

Dual-luciferase reporter gene experiment

Reporter gene vectors carrying the promoter sequence of PKM2, PDK1 and BNIP3 were designed and synthesized. Subsequently, the reporter gene, CHK2 plasmid and renilla luciferase plasmid was co-transfected into HEK293-CHK2-KO cells for 48 h under normoxia or hypoxia. The dual-luciferase detection kit (Promega, Madison, WI) was utilized to detect the luciferase activity.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and western blot assays

We applied the previously described Co-IP and western blot assays [35].

In vitro GST pull-down assay

Escherichia coli BL21 cells seeded in lysogeny broth medium with 100 mg/mL ampicillin were used to express proteins with GST tag and His tag. A 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside solution was added and left for 3 h at 30 °C to produce protein overexpression. The cells were again suspended in bacterial lysis solution (20% glucose, 10% glycerol, 2 mM MgCl2, 50 mM Tris–Cl at pH 8.0). After ultrasonication, the GST-proteins were purified using glutathione sepharose 4B GST-tagged protein purification resin (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) in compliance with the manufacturer’s protocol, while the His-proteins were purified using HisTRAP Fast Flow columns (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA). Full-length HIF-1α and CHK2 proteins with His-tag were used as Input. The pull-down assay was performed between GST tag proteins and His coupled proteins. Empty GST-tagged protein was performed as the negative control. We triple-washed using binding buffer, and then we eluted the proteins with 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer for succeeding western blot analysis.

Clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 knockout (KO) cell lines

KO of the target genes was carried out in HEK293 cells co-transfected with single-guide RNA sequences inserted into the Lenti-CRISPRv2 plasmid, along with the viral packaging plasmids psPAX2 and pMD2G. At 6 h post transfection, we changed the medium and collected and filtered the viral supernatant through a 0.45-μm membrane. We used puromycin at 1 μg/ml for 2 weeks to select the targeted cells infected by the viral supernatant. The single-guide RNA sequence targeting CHK2 was GGTCCTGCTGAGCCATGA.

In vivo studies

We held BALB/C nude mice (female; age 4–6 weeks; body weight, 14–16 g) under a normal laboratory environment in an explicit pathogen-free chamber. A total of 200 μL of PBS/Matrigel (v:v) was subcutaneously injected via the rear flanks, containing 1 × 106 H1299 cells. When the tumor size was about 60 mm3, DMSO or the CHK2 inhibitor (1 mg/kg) was administered intraperitoneally on alternate days for 20 days after randomly grouped (n = 5/group). The long and short diameters of subcutaneous tumors were measured weekly. Tumor volume was then calculated via 0.5236 × r12 × r2 (r1 < r2); 1 × 106 H1299 cells that expressed WT HIF-1α or the T645A mutant firmly in PBS/Matrigel (v:v) were subcutaneously injected via the rear flanks in a volume of 200 μL. On the 28th day, the mice were then euthanized by cervical dislocation. We cultured the tumors, fixed them, embedded them in paraffin, sectioned them, and either marked them with hematoxylin and eosin or immunostained with specific Abs. The guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals, which can be found at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK54050/, were followed for the animal study procedure, which was approved by the China Medical University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (approval no. CMUKT2023223).

Clinical samples

Paraffin-embedded sections of principal non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) tissue specimens (n = 50) were collected at the time of resection between 2021 and 2022 at Shengjing Hospital (China Medical University) and immediately stored in liquid nitrogen until protein extraction for IHC analysis. All patients were detected with NSCLC following the American Joint Committee Cancer guidelines. The study procedure was approved by the China Medical University Medical Ethics and Human Clinical Trial Committee (approval no. AF-SOP-07-1.1-01), and it adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki’s ethical guidelines for medical research involving human participants. All participants wrote informed consent before proceeding with this study.

Statistical analysis

We presented the data as mean ± standard error. Significance was set at 0.05. The One-way ANOVA was used for the multiple groups, while the Student’s t-test was employed to compare two groups. Two-way ANOVA was conducted for groups with two independent variables. Simple linear regression analysis was used to analyze correlations. We performed all statistical analyses using either GraphPad 8 (Software Inc., CA) or SPSS 17.0 version (IBM, USA).

Responses