S-ketamine exposure in early postnatal period induces social deficit mediated by excessive microglial synaptic pruning

Introduction

Approximately 1.5 million infants and young children worldwide require surgical treatment under general anesthesia per year [1]. Nevertheless, the long-term impact of early postnatal exposure to general anesthetics on neurocognitive development remains controversial. According to the evidence from large-scale multicenter clinical studies, such as Pediatric Anesthesia Neurodevelopment Assessment (PANDA), Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids (MASK) and General Anesthesia or Awake-regional Anesthesia in Infancy (GAS), no detectable differences in general intelligence quotient (IQ) were observed in children and adolescence who have underwent a short-term general anesthesia before 3 yr [2,3,4]. However, evaluations of neurodevelopmental outcomes by parents and caregivers also mentioned alterations of sociability and executive function in children after exposure to general anesthesia in early childhood [5]. Meanwhile, considerable evidence from preclinical studies, especially for non-human primates (NHPs) experiments, indicated that exposure to volatile anesthetics in early life might give rise to deficits of close social behaviors and dendritic heteroplasia without obvious decline in learning and memory [6, 7]. These phenomena suggest that social cognition might be more susceptible to general anesthesia, and their influence on neurodevelopment would be concealed due to the hyposensitivity of available diagnostic tools.

The development of synapses is a cardinally essential biological processes in central nervous system at early postnatal periods, including synaptic formation, maturation, pruning etc. [8], contributing to neural circuit assembling, neuronal excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) balance and long-term plasticity [9]. The aberrant synaptic development mediates a series of psycho-behavioral abnormalities, such as social avoidance, repetitive stereotyped behaviors and motor dysfunction [10, 11], which are considered as the core symptoms of autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) [12]. Indeed, previous studies have demonstrated that early exposure to general anesthetics would potentially increase the risk of ASD [13]. However, whether the neurodevelopmental abnormalities associated with general anesthesia are distinct to ASD also remains unclear.

The homeostasis of neuronal E/I balance, especially the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and hippocampal CA2, is essential for the regulation of social behaviors based on the normal dendritic structures [14, 15]. During the early postnatal period, microglia play an important role in dendritic development. Microglia modulate synaptic competition, remodeling and pruning in an activity-dependent manner through complement cascade and MHC class I [16]. Synaptic pruning mediated by microglia includes recognition, phagocytosis and digestion [17]. Through “eat-me” signals such as phosphatidylserine, calreticulin, Gas6, and complement proteins binding to the corresponding phagocytic receptors on the surface of microglia, the neuronal signaling mediated by these receptors is specifically initiated, inducing cytoskeletal protein remodeling, synaptic phagocytosis and finally synaptic digestion through the fusion of phagosome and lysosome [18, 19]. Furthermore, microglia are sensitive to various types of general anesthetics. Both isoflurane, ketamine or urethane could modulate microglial process surveillance through norepinephrine signaling [20]. Correspondingly, microglia could enhance post-anesthesia neuronal activity by shielding inhibitory synapses through microglial β2-adrenergic receptors [21]. Therefore, we hypothesize that microglia potentially affect synaptic pruning after general anesthesia during neurodevelopment, resulting in a lasting impact on social cognitive development throughout the adolescent period.

Ketamine is a widely used dissociative anesthetic in pediatric surgery due to its minor respiratory and circulatory inhibition [22]. In recent years, the therapeutic effect of subanesthetic ketamine or S-ketamine against psychiatric disorders has been exhaustively elucidated [23, 24]. Of note, subanesthetic dose of S-ketamine through intravenous injection before childbirth via cesarean delivery was also used for preventing neonatal depression [25]. Although studies in rodents have pointed out that ketamine damages neurocognition and dendritic development mediated by disrupted synapse unsilencing, neuronal apoptosis, etc. [26, 27], the sustained influence of ketamine administration in infancy on subsequent cognitions and synaptic development remains unclear. In current study, we compared the influence of a single anesthetic dose exposure to S-ketamine and sevoflurane at postnatal day 7 (P7) on following neurocognitions in adolescent mice (P28-P30). To precisely distinguish the behavioral changes in rodents, we utilized two novel behavior analysis toolbox – Brain Atlas and Social Behavioral Atlas (SBeA) based on deep learning algorithm for accurate and quantitative analysis of spontaneous behaviors and sociability among multi-animals [28, 29]. Combining with tissue clearing, transcriptomics and electrophysiology techniques, we further explored neural mechanisms underlying S-ketamine exposure on microglial synaptic pruning, dendritic structure development, and synaptic neurotransmission. This study aimed to illustrate the neural mechanism of S-ketamine exposure at early postnatal period mediating social deficit during neurocognitive development.

Methods and materials

Animals

C57BL/6 J (C57) mice were supplied by Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. The pups of C57 mice were generated by breeding pairs purchased above. Cx3cr1-CreER mice were kind gifts from Professor LJ. Wu. Animals were kept in a controlled environment with temperatures ranging from 18 to 23 °C and humidity levels between 38 and 42%. Mice followed a 12-h light/12-h dark illumination schedule and were provided with an unrestricted diet and water. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with approved principles of laboratory animal care and ethical approval by the Fourth Military Medical University.

Anesthesia administration

The day of birth was labeled as P0. P7 pups were injected (i.p.) with a bolus of S-ketamine or equivalent volume of saline on P7, and were sacrificed 6 h after S-ketamine administration, as well as on P14, P21 and P28 for morphological and biochemical experiments.

Behavior tests

Behavioral tests were performed at around the same time in the light circle, including three-dimensional (3D) free-moving spontaneous behavior, 3D free-social behavior, three-chamber test, social reciprocal interaction, marble burying, self-grooming, open field test (OFT), elevated-plus maze (EPM), novel object recognition (NOR) and Barnes maze.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence detection of ionized calcium binding adapter molecule-1 (Iba1), CD68, postsynaptic density protein 95 (PSD95), and parvalbumin (PV) was performed by standard procedures.

Tissue clearing

The neonatal mice were intracerebroventricularly injected with AAV-sparse-NCSP-RFP virus bilaterally on P0. IMARIS 10.1 was utilized to create a 3D surface rendering of the neuron and the surrounding microglia.

Microglial isolation

Microglia isolation was carried out based on the manufacturer’s standard protocol from Miltenyi Biotec. Single cell dissociation and further experiments were described in Supplementary Information.

RNA sequencing

TRIZOL reagent kit (Invitrogen, USA) was used to extract total RNA from microglia of the whole brain on P7, P14, P21 and P28. RNA sequencing was conducted by the Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co. (Guangzhou, China).

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA of PFC, hippocampal CA2, and isolated microglia was extracted and detected by qRT-PCR. The detailed procedures were described in Supplementary Information.

Western blot analysis

The protein of primary microglia was extracted, and the quantitative analysis of Stat1, Arg1 and β-actin was performed according to previous method [30].

Cell transfection

Stat1-targeting small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were produced by Tsingke Biotechnology (Beijing, China). Details of the experiments can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

The EZ ChIP Kit (Millipore, Billerica, MD, USA) was used to perform the assay, following the protocols provided by the manufacturer.

Neuron-microglia co-cultures

Co-cultures of microglia and neurons from the PFC followed previously established method [31].

Arginase inhibitor administration

The selective arginase inhibitor, nor-NOHA, was injected i.p. into C57 pups from P2 to P6 at 30 mg/kg daily before receiving a single-dose of S-ketamine on P7 [32].

Lentivirus injection into lateral ventricles

Neonatal mice (P0) were injected bilaterally with lentivirus into lateral ventricles as previous method [33]. Further experiments were conducted 1–4 weeks after virus injection.

Slice preparation and electrophysiology

Electrophysiology recording was conducted on brain slices containing PFC and hippocampal CA2. Data were analyzed using Clampfit 10.0 software along with the Mini Analysis Program (Synaptosoft, Leonia, NJ, USA).

Golgi staining

Following the previous procedures as described [34], the manufacturer’s instructions of FD Rapid Golgi Stain kit (FD NeuroTechnologies, Baltimore, MD) were referred to prepare brain tissues and perform staining.

Proteome analysis

Three PFC tissues were randomly selected from three experimental groups as biological replicates, and proteins were extracted on P7, P14, P21 and P28. Proteome analysis was conducted by the Gene Denovo Biotechnology Co. (Guangzhou, China).

Statistical analysis

The experimenters were blind to the group assignment during all experiments and analysis. The sample size of each group was comparable to those typically used in related studies. Mice were randomly assigned to treatment using a random number table. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 9.0. All results are presented as mean ± SEM. The number of samples was described in figure legends. The normality test was performed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. The homogeneity of variance test was performed by Levene’s test. Two different sample comparisons were conducted using a two-tailed unpaired or paired t test. Wilcoxon Signed Rank test and Mann–Whitney U test were used when normality of samples was failed. For multiple comparisons, two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak post hoc test were conducted. Details of the statistical analyses can be found in Supplementary Table 1. P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Results

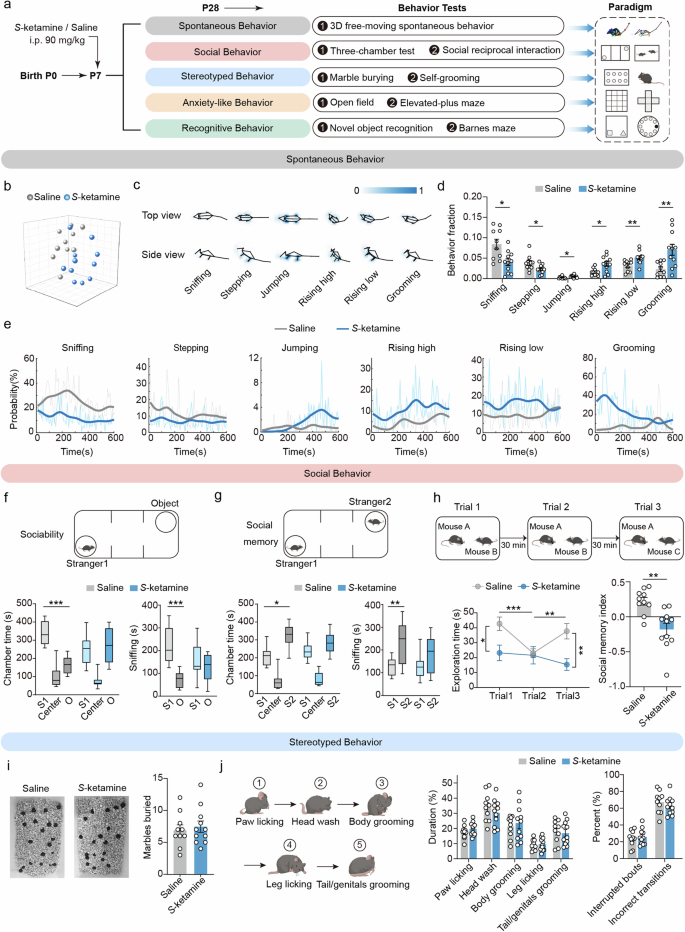

Behavioral changes induced by S-ketamine exposure at early postnatal period

We firstly confirmed the general anesthetic effects of a series of S-ketamine concentration, including 70 mg/kg, 80 mg/kg, 90 mg/kg, 95 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg one bolus. The rating criteria of consciousness after anesthesia for neonatal mice was optimized based on the previous scoring criteria [35]. Considering the survival rates (Supplementary Fig. 1a) and the sedative effect after S-ketamine administration (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c), the anesthetic concentration of 90 mg/kg was identified as the optimal concentration, without obvious alterations in mouse arterial pH, PaCO2, PaCO2 and SaO2 (Supplementary Fig. 1d). To investigate the effects of S-ketamine exposure at early postnatal period on social behaviors and distinguish with ASD-like symptoms, we performed a set of behavior tests in adolescent mice (Fig. 1a). Spontaneous behaviors were evaluated using a hierarchical 3D-motion learning framework and displayed 40 behavioral motifs (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). We observed that the saline and S-ketamine groups were well classified into two clusters in the low-dimensional space (Fig. 1b). The S-ketamine-exposed mice exhibited reduced exploring (stepping and sniffing), but more jumping, rising (both high and low), and self-grooming (sniffing, P < 0.05; stepping, P < 0.05; jumping, P < 0.05; rising high, P < 0.05; rising low, P < 0.01; grooming, P < 0.01, Fig. 1c–e). In the three-chamber social paradigm, control mice directly engaged more in the chamber with a stranger mouse than with an object in the test of sociability (P < 0.001, Fig. 1f), whereas S-ketamine-exposed mice exhibited no interest in side chambers. Sniffing time, a more sensitive parameter reflecting sociability, was consistent with the exploration time in different side chambers (P < 0.001, Fig. 1f). Furthermore, control mice preferred remaining in the side chamber with the novel mouse than with the familiar mouse (P < 0.05), as well as sniffing with the novel mouse during social memory test (P < 0.01, Fig. 1g). In contrast, S-ketamine-exposed mice showed no preference between the novel and familiar mouse (Fig. 1g).

a Schematic of experimental design for S-ketamine exposure and behavior tests. b Low-dimensional representation of saline and S-ketamine groups. The 21 samples in 3D space were dimensionally reduced from 40-dimensional movement fractions, and they are well separated. c, d Averaged skeletons c and comparison of fraction d of 6 different behavior movements in two groups. e Comparison of probability of 6 behavior movements across time. The bold traces were derived from the mean of the percentage of all the samples through Gaussian smoothing. f, g Diagram (top) and time spent in each chamber (bottom left) and close interaction (bottom right) with O and S1 in the sociability test f and with S1 and S2 in the social memory test g of three-chamber test. h Protocol of social reciprocal interactions including three trials (top), social exploration time (bottom left) and social memory index (bottom right) in the direct interaction of mice from two groups. i Representative results (left) and quantification (right) of buried marbles of two groups in the marble burying test. j Diagram of mouse grooming pattern (left), the proportion of duration in regional grooming (middle), and the percentage of interrupted bouts and incorrected transitions in grooming sub-regions (right). Saline, n = 10 mice, S-ketamine, n = 11 mice. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistical information.

Correspondingly, we detected the time duration of direct social interaction in homecage, which reflected spontaneous social contact under a physiological circumstance. A significant distinction was observed in the duration of social exploration during trial 1 after S-ketamine exposure (F(2, 38) = 9.064, P < 0.05, Fig. 1h), as well as the social time during trial 3 (P < 0.01, Fig. 1h). Along with the performance shown above, S-ketamine-exposed mice could not achieve social memory encoding so that no variation of time duration between trial 1 to trial 2 and trial 2 to trial 3. Social memory index was notably decreased after S-ketamine exposure (P < 0.01, Fig. 1h). We then evaluated the repetitive behaviors, including marble burying and grooming behaviors. The Saline and S-ketamine groups buried similar amounts of marbles (Fig. 1i). The pattern of rodent grooming proceeds in a cephalo-caudal direction, and the proportions of duration spent in paw licking, head washing, body grooming, leg licking and tail/genital grooming were comparable in two groups, as well as the percentage of interrupted bouts and incorrected transitions (Fig. 1j). In addition to these core phenotypes-abnormal social interactions and stereotyped repetitive behaviors in ASD, elevated anxiety-like behaviors and cognitive inflexibility are common concomitant symptoms [36, 37]. Thus, we performed the EPM and OFT to determine the anxiety-related behaviors in adolescent mice. In EPM test, the S-ketamine-exposed mice spent similar time in the open arms and displayed similar percentage of open arm entries to the control mice (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Track in open field test showed that the time in center and total distance were not affected by S-ketamine (Supplementary Fig. 3b), indicating no change occurred in locomotion and anxiety. Additionally, there was no significant difference in the escape latency and duration of target quadrant in the probe trial between two groups during acquisition phase of Barnes maze (Supplementary Fig. 3c), so as reversal phase (Supplementary Fig. 3d), reflecting no impairments in the cognitive flexibility after S-ketamine exposure. Likewise, S-ketamine-exposed mice showed no difference in the discrimination index compared to the control mice in NOR test (Supplementary Fig. 3e), suggesting S-ketamine exposure at early postnatal period had no effect on working and spatial memory of adolescence in mice.

Clinically, subanesthetic doses of S-ketamine are widely used for treatment of mental illness. To confirm whether subanesthetic S-ketamine will trigger similar symptoms, the neonatal mice were injected with S-ketamine (25 mg/kg) on P7 and subjected to autism-related behavior tests in adolescence (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Similar to the control mice, S-ketamine-exposed mice exhibited preference toward the stranger/familiar mouse in three-chamber test (chamber time, P < 0.05; sniffing time, P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 4b, c) and social reciprocal interaction test (F(2, 40) = 0.1712, P = 0.8432, Supplementary Fig. 4d). No significant difference in stereotyped marble burying and self-grooming behaviors was observed between saline and S-ketamine groups (Supplementary Fig. 4e, f), as well as anxiety-like symptoms in OFT and EPM test (Supplementary Fig. 4g, h). The recognitive levels detected in the Barnes maze and NOR test in two groups were consistent (Supplementary Fig. 4i to k). In addition, S-ketamine was also utilized in adult patients. Thus, adult mice were injected with S-ketamine (90 mg/kg) at 8 weeks, then subjected to social behavior tests 24 h after S-ketamine administration (Supplementary Fig. 5a). S-ketamine-exposed mice spent more time exploring/sniffing the stranger mouse in the sociability phase (chamber time, P < 0.001; sniffing time, P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 5b), as well as the novel mice in the social memory phase of three-chamber test (chamber time, P < 0.01, sniffing time, P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 5c). In the social reciprocal interaction test, S-ketamine exposure did not induce different social performance between two groups (F(2, 46) = 1.827, P = 0.1724, Supplementary Fig. 5d). Therefore, it is suggested that the effects of S-ketamine on social performance are dose- and age-dependent.

To determine whether the social deficits were unique to early-life S-ketamine exposure, we also explored the effects of another commonly used anesthetic in pediatric surgery, sevoflurane. Similarly, neonatal mice were administrated 3% sevoflurane for 2 h on P7, and applied with autism-related behavior tests (Supplementary Fig. 6a). In the three-chamber test, the sevoflurane group showed apparent interest in the stranger mouse in the sociability phase (chamber time, P < 0.001; sniffing time, P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 6b), as well as the novel mouse in the social memory phase (chamber time, P < 0.05; sniffing time, P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 6c). In the social reciprocal interaction test, no significant differences in variation tendency of social exploration and social memory index were found between two groups (F(2, 36) = 2.829, P = 0.0723, Supplementary Fig. 6d). Likewise, the sevoflurane-exposed mice did not exhibit abnormal stereotyped marble burying and self-grooming behaviors compared to the controls (Supplementary Fig. 6e, f). The results of anxiety-like behaviors showed that there were no significant differences in the percentage of open arm time and entries in the EPM test (Supplementary Fig. 6g), as well as center time and total distance in the OFT between the saline and sevoflurane mice (Supplementary Fig. 6h). Additionally, the recognitive behaviors in the Barnes maze and NOR test were not affected by sevoflurane (Supplementary Fig. 6i–k). Thus, early-life sevoflurane exposure does not trigger abnormal social behaviors or other autistic symptoms in adolescence. Together, these findings demonstrated that the S-ketamine exposure in early postnatal period could induce social deficits in adolescence, accompanied by abnormalities in spontaneous behaviors.

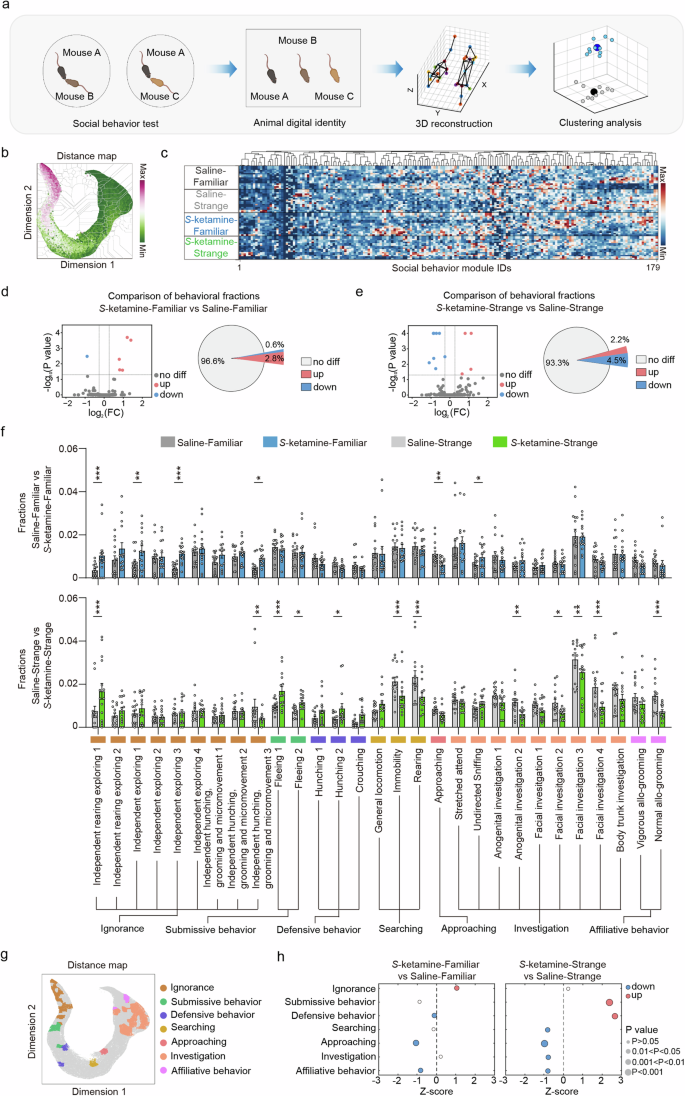

Deficits of spontaneous sociability in adolescent mice with S-ketamine exposure

Recent deep learning algorithm promoted a more comprehensive depict of animal social behaviors [29]. Here, we used SBeA to quantify the free social behaviors (Fig. 2a) and construct a low-dimensional representation of movements (Fig. 2b), aiming to reveal S-ketamine-induced subtle social behavioral changes towards strange/familiar mice. The cluster diagram displaying the social behaviors with potential differences among groups (Fig. 2c).

a Pipeline of mouse behavior recording and analysis via 3D-motion learning framework. b Social behavior atlas with distance map of all mice. c The cluster gram of social behavior modules across 4 groups of mice. d, e Volcano plot and pie chart representing the number of differential behavior modules between saline and S-ketamine groups when interacting with a familiar mouse d and a stranger mouse e. Red represents increased phenotype and blue indicates decreased phenotype. f Comparison of the fractions of social behavior modules between saline and S-ketamine groups when interacting with a familiar mouse (top) and a stranger mouse (bottom). g SBeA of differential social behaviors. h Comparison of the merging fractions of seven social behaviors when interacting with a familiar mouse (left) and a stranger mouse (right). n = 15 mice per group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistical information.

The social interactions with familiar mice of the S-ketamine mice showed marked differences in 6 behavior phenotypes compared to the saline mice, including 1 (0.6%) decreased and 5 (2.8%) increased phenotypes (Fig. 2d). When interacting with stranger mice, the S-ketamine group displayed 8 (4.5%) significantly reduced and 4 (2.2%) increased behavior phenotypes than the control group (Fig. 2e). The behavior modules were classified into seven social behaviors based on the characteristics of body movements and mouse ethogram (Fig. 2f), and were mapped to behavior atlas (Fig. 2g). All postures of various social behaviors are illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 7. The seven social behaviors highlighted significant differences among two groups. Specifically, S-ketamine group exhibited more ignorance (P < 0.05), less approaching and affiliative behaviors towards familiar mice than saline group (approaching, P < 0.01; affiliative behavior, P < 0.05, Fig. 2h left). However, S-ketamine group also showed relatively higher fractions of defensive behaviors (P < 0.05). In addition, there were even more dramatic differences between two groups when interacting with stranger mice, displaying as more submissive and defensive behaviors (submissive behavior, P < 0.001; defensive behavior, P < 0.01), but less searching, approaching, investigation and affiliative behaviors in S-ketamine group (searching, P < 0.05; approaching, P < 0.001; investigation, P < 0.05; affiliative behavior, P < 0.05, Fig. 2h right).

Considering that social behavioral differences exhibited various patterns in saline and S-ketamine mice, we next compared the behavioral differences between familiar and stranger mice in two groups. Social interactions with familiar mice in saline group displayed significant differences in 17 behavior phenotypes compared to the interaction with stranger mice, including 12 (6.7%) decreased and 5 (2.8%) increased phenotypes (Supplementary Fig. 8a, c first row). However, the social interactions with familiar mice in S-ketamine group displayed 4 (2.2%) significantly reduced phenotypes and 7 (3.9%) increased phenotypes (Supplementary Fig. 8b, c second row). To comprehensively present the details of behavioral differences, the word cloud was utilized to build up the social behavior fingerprints to reduce the complexity of comparisons (Supplementary Fig. 8d), suggesting that S-ketamine exposure increased more ‘independent’ and less ‘investigation’ words no matter interacting with strange or familiar mice. By merging the social behaviors of the same category, it was found that the interaction between saline group and familiar mice had more frequent submissive and defensive behaviors (submissive behavior, P < 0.01; defensive behavior, P < 0.001), and reduced investigation and affiliative behaviors compared to stranger mice (investigation, P < 0.01; affiliative behavior, P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 8e left). Nevertheless, S-ketamine led to difference in social ignorance and affiliative behaviors between the interaction with familiar and stranger mice (ignorance, P < 0.05; affiliative behavior, P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 8e right).

In conclusion, S-ketamine exposure exhibited impacts both on interactions with familiar and stranger mice. These subtle social behaviors are organized together as fingerprints to indicate that S-ketamine in early postnatal period induces social avoidance and lack of social interests, which are comprehensive behavior complements of limited parameters of the three-chamber test.

S-ketamine exposure disrupted dendritic structure and hyperactivated excitatory synaptic transmission

Social behavior is closely related to the regulation of multiple brain regions, among which the PFC is a central hub of the social brain [38], and the hippocampal CA2 subregion was considered essential for social memory [39]. Furthermore, the structural and functional alterations in pyramidal neurons are reported to affect social behaviors [40, 41]. Thus, Golgi staining was performed to examine the variation of synaptic structures in pyramidal neurons after S-ketamine exposure. Sholl analysis showed an elevation in the basal dendritic complexity of PFC pyramidal neurons of S-ketamine-exposed mice (F(9, 198) = 7.704, P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 9a, b). The S-ketamine-exposed neurons in the PFC showed a markedly increased number of intersections at the distance of 50–90 μm to the soma (Supplementary Fig. 9b right). Besides, S-ketamine-exposed mice displayed less apical (P < 0.001) and basal dendritic spine densities than control mice in PFC (P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 9c, d), accompanied by a higher ratio of immature spines (filopodia and long thin spines) and a lower ratio of mature spines (mushroom spines) (apical spines: long thin, P < 0.05; stubby, P < 0.05; mushroom, P < 0.01; basal spines: filopodia, P < 0.01; long thin, P < 0.01; mushroom, P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 9e, f). Next, we conducted whole-cell patch recordings on PFC pyramidal neurons. S-ketamine-exposed mice showed significantly increased frequencies (P < 0.001) and amplitudes of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current (sEPSC) compared to the control mice (P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 9g), without changes in the frequencies and amplitudes of spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic current (sIPSC) (Supplementary Fig. 9h), which was consistent with the variation trend in the frequencies and amplitudes of miniature EPSC (mEPSC) and miniature IPSC (mIPSC) (Supplementary Fig. 9i, j).

We also detected the morphology and synaptic transmission of pyramidal neurons in CA2. There was no difference in the apical and basal dendritic complexity of CA2 pyramidal neurons between two groups (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). But S-ketamine-exposed mice also displayed less apical (P < 0.01) and basal dendritic spine densities (P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 10c, d), with a higher ratio of filopodia-like spines in the apical and basal dendrites (apical, P < 0.05; basal, P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 10e, f). Likewise, the amplitudes of sEPSC (P < 0.001) but not frequencies were elevated in CA2 pyramidal neurons of S-ketamine-exposed mice without any change in the frequencies and amplitudes of sIPSC (Supplementary Fig. 10g, h).

To verify whether early postnatal S-ketamine exposure affects the function of inhibitory neurons in the PFC, we bred a PV-Cre line crossed to a Rosa26-STOP-tdTomato (tdT) reporter line (Ai9 mice) to obtain PV::tdT mice. Since PV was not expressed until P14, we conducted quantitative analysis of PV+ neurons in different layers and subregions of PFC on P14, P21 and P28 (Supplementary Fig. 9k). It was observed that there was no difference in the number of PV+ neurons in different layers (layer II/III and layer V) and subregions (PrL and IL) of PFC between two groups at different stages of neurodevelopment (Supplementary Fig. 9l). S-ketamine exposure did not change the amplitudes or frequencies of sEPSC/sIPSC (Supplementary Fig. 9m–o) and mEPSC/mIPSC in PFC PV+ neurons of adolescent mice (Supplementary Fig. 9p, q). This suggests that early postnatal S-ketamine exposure has no effect on the distribution and function of PFC PV+ neurons. Together, these results provide evidence that S-ketamine-exposed mice showed deficits in the morphology and maturation of the PFC pyramidal neurons, which possibly caused reduced excitability within the neural network of the PFC.

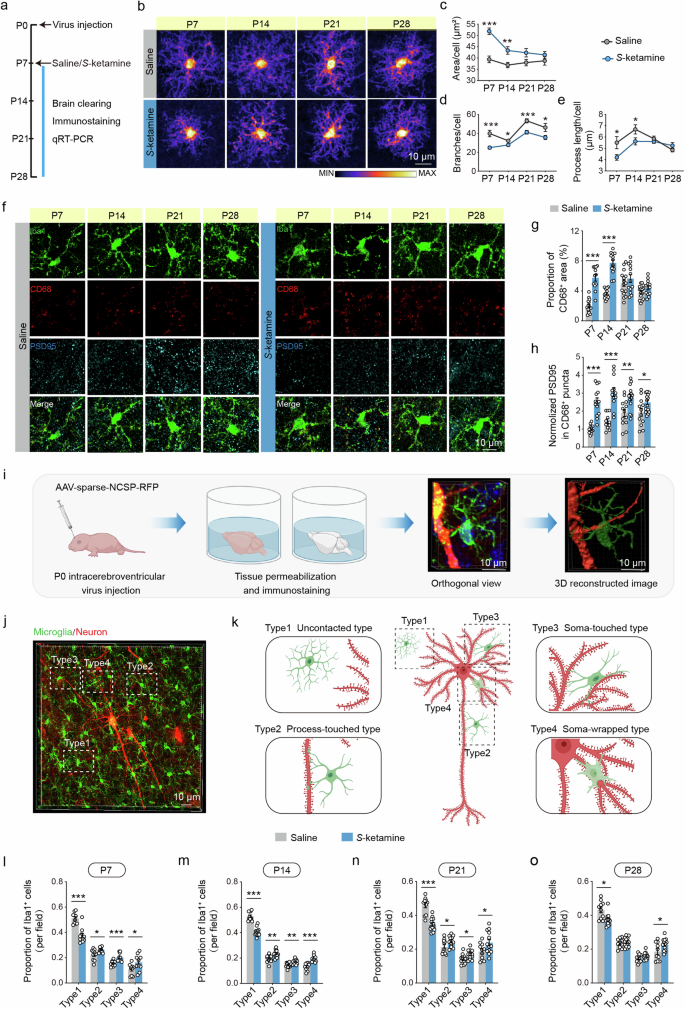

S-ketamine exposure activated microglia and enhanced synaptic pruning

Microglia are involved in synapse remodeling through synaptic pruning in early postnatal period, and dysregulated synaptic pruning is linked with social deficits [42]. To investigate whether the disrupted dendritic structure of pyramidal neurons was mediated by microglia, the microglial morphological characteristics and capabilities of synaptic pruning in PFC and hippocampal CA2 were specifically evaluated on P7, P14, P21 and P28 (Fig. 3a). The microglia in the PFC of S-ketamine-exposed mice were highly activated (Fig. 3b), as the soma area obviously enlarged from P7 to P14 (P7, P < 0.001; P14, P < 0.01, Fig. 3c), whereas the number of branches reduced from P7 to P28 (P7, P < 0.001; P14, P < 0.05; P21, P < 0.001; P28, P < 0.05, Fig. 3d), and the process length decreased from P7 to P14 (P7, P < 0.05; P14, P < 0.05, Fig. 3e). However, the microglia in CA2 of S-ketamine-exposed mice only displayed enlarged soma from P7 to P14 (P7, P < 0.001; P14, P < 0.05) and increased branches on P7 (P7, P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 11a–d).

a Schematic illustrating the experimental protocol for microglial assessments. b Heatmaps of overlapped microglia to assess their morphological alterations in different developmental stages in the PFC of saline and S-ketamine groups. Scale bar: 10 μm. c–e Quantification of microglial morphologic parameters, including area of cell body c, branch numbers d and average process length e in the PFC. n = 3 mice per group, average of 5–8 cells from each mouse. f Representative confocal images of Iba1 (green), CD68 (red), PSD95 (blue) in the PFC of saline and S-ketamine-exposed mice. Scale bar: 10 μm. g, h Proportion of CD68+ area in microglia g and quantification of PSD95+ area in CD68+ puncta h in the PFC of two groups. n = 3 mice per group, average of 4–7 cells from each mouse. i Schematic of experimental design for neonatal virus injection, brain clearing and 3D reconstruction. j, k A representative orthogonal view j and schematic illustrations k of microglia and a neuron in the PFC, displaying different contact intensity. The microglia were classified into four types, including uncontacted type (type 1), process-touched type (type 2), soma-touched type (type 3) and soma-wrapped type (type 4). Scale bar: 10 μm. l–o Comparison of the proportion of different typed microglia around a neuron in saline and S-ketamine groups on P7 l, P14 m, P21 n and P28 o. n = 3 mice per group, average of 4–6 neurons from each mouse. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistical information.

By coimmunostaining of CD68 (a phagolysomal microglial marker) and PSD95 (a postsynaptic marker) with Iba1 (Fig. 3f), it was observed that the immunoreactivity of CD68 was obviously increased in the PFC of S-ketamine group from P7 to P14 (P7, P < 0.001; P14, P < 0.001, Fig. 3g). We also found significantly more PSD95 immunoreactivity inside CD68+ lysosomes from P7 to P28 in the PFC of S-ketamine-exposed mice than the control mice (P7, P < 0.001; P14, P < 0.001; P21, P < 0.01; P28, P < 0.05, Fig. 3h), reflecting that microglial phagocytosis of excitatory synapses was enhanced after early-life S-ketamine exposure. In CA2 of S-ketamine group, the immunoreactivity of CD68 was transiently increased on P7 (P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 11e, f), but immunoreactivity of PSD95 inside CD68+ lysosomes was also increased from P7 to P28 (P7, P < 0.01; P14, P < 0.05; P21, P < 0.05; P28, P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 11e, g). These results suggest that the microglia in the PFC are more vulnerable to early-life S-ketamine exposure than that in hippocampal CA2. We further detected mRNA levels of microglial receptors in the PFC related to synaptic pruning, including CR3 (CD11b/CD18), CD68, Cx3cr1, Trem2 and P2ry12 [43,44,45]. S-ketamine exposure significantly increased mRNA levels of CD68, CD11b and CD18 (CD68: P7, P < 0.05; P14, P < 0.05; CD11b: P7, P < 0.001; P14, P < 0.001; P21, P < 0.001; P28, P < 0.01; CD18: P7, P < 0.01; P14, P < 0.01; P21, P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 12a–c). Whereas, the mRNA levels of Cx3cr1 and Trem2 were not affected by S-ketamine at various stages (Supplementary Fig. 12d, e). The mRNA level of P2ry12 was transiently decreased after S-ketamine exposure on P7 (P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 12f). Different from PFC, S-ketamine injection only transiently elevated the mRNA levels of CD11b, CD68 and decreased P2ry12 level (CD68: P7, P < 0.05; CD11b: P7, P < 0.05; P14, P < 0.05; P2ry12: P7, P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 11h, I, m), but not of CD18, Cx3cr1 and Trem2 in CA2 (Supplementary Fig. 11j–l).

To delineate the potential links between the susceptibility of microglia to S-ketamine exposure at early postnatal period and neuronal dendrites, we detected the contact intensity between microglia and dendrites. Intracerebroventricular virus injection of AAV-sparse-NCSP-RFP was adopted on P0, and we utilized tissue permeabilization approach combined with immunostaining for microglia on P7, 14, 21, 28 (Fig. 3i). By 3D reconstruction, the perineuronal microglia were classified into four types based upon their contact intensity, including uncontacted type (type 1), process-touched type (type 2), soma-touched type (type 3) and soma-wrapped type (type 4) (Fig. 3j, k) (Supplementary Fig. 13a, b). Compared with the control mice, the quantities of uncontacted microglia around a neuron on P7 were significantly decreased (P < 0.001), while the quantities of process-touched type (P < 0.05), soma-touched type (P < 0.001) and soma-wrapped type were greatly increased in the PFC of S-ketamine group (P < 0.05, Fig. 3l). Similar results were obtained on P14 (type1, P < 0.001; type2, P < 0.01; type3, P < 0.01; type4, P < 0.001, Fig. 3m) and P21 (type1, P < 0.001; type2, P < 0.05; type3, P < 0.05; type4, P < 0.05, Fig. 3n). However, the difference between the number of saline and S-ketamine groups on P28 only existed in uncontacted and soma-wrapped microglia (type1, P < 0.05; type4, P < 0.05, Fig. 3o).

To identify the sensitivity of microglia to S-ketamine exposure in different brain regions, we performed immunostaining for Iba1 in the whole brain section on P7, P14, P21 and P28. We observed that the total quantities of microglia in isocortex (P21, P < 0.05; P28, P < 0.05) and hippocampus changed remarkably after S-ketamine injection (P21, P < 0.05; P28, P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 14a–i). The comparison of microglial quantities in different subregions were displayed as Supplementary Fig. 15a–h. We also assessed the microglial morphological characteristics in other brain regions related to social behaviors, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and basolateral amygdala (BLA), on P7, P14, P21 and P28 (Supplementary Fig. 16a, b). The microglia in ACC of S-ketamine-exposed mice displayed enlarged soma (P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 16c) and shortened process on P7 (P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 16e), and reduced branches from P7 to P14 (P7, P < 0.01; P14, P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 16d). However, the microglia in BLA only showed enlarged soma on P7 (P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 16f), without alterations in branch number and process length (Supplementary Fig. 16g, h). Together, these findings reveal that early-life S-ketamine exposure induces enhancement of microglial synaptic pruning in postnatal development, especially in the PFC.

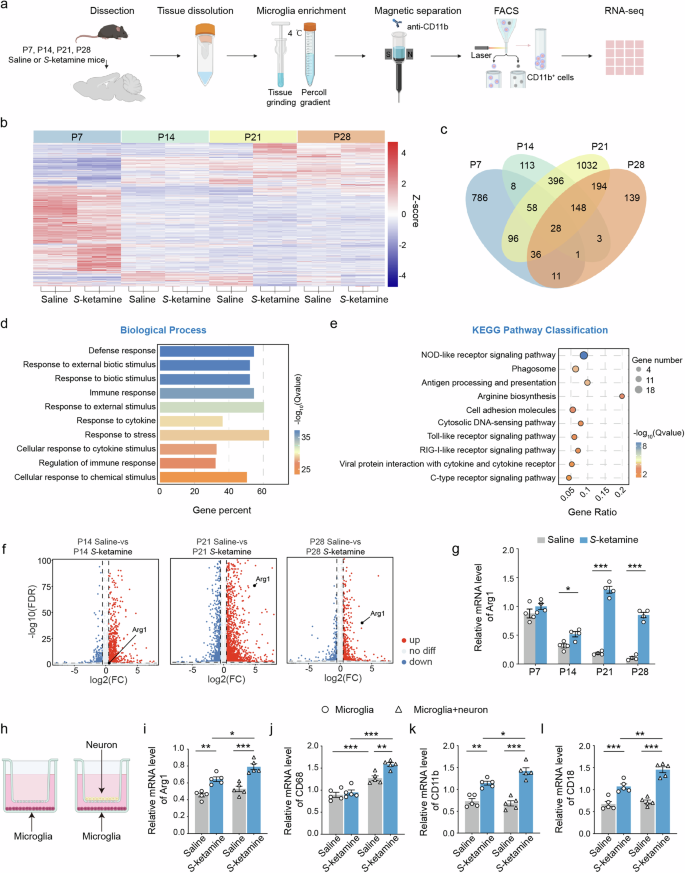

S-ketamine exposure directly activated Stat1-Arg1 pathway of microglia in the PFC

Considering that S-ketamine exposure caused impacts on microglial activity and function in different brain regions, the brains were isolated on P7, P14, P21 and P28 and their microglia were screened out for further analysis by RNA sequencing (Fig. 4a). There were hundreds of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) after S-ketamine exposure (Fig. 4b), but only 28 DEGs on four timepoints. Given that the expressions of critical genes did not alter apparently at once after S-ketamine exposure, 148 common DEGs on P14, P21 and P28 were involved in the analysis (Fig. 4c). Gene ontology (GO) analysis on these 176 DEGs showed a notable enrichment in biological processes related to defense response against external stimulus (Fig. 4d). Notably, the DEGs within arginine biosynthesis (Arg2, Nos2, Ass1, Arg1) in KEGG pathways took up the highest proportion (Fig. 4e).

a Microglia were isolated from mice on P7, P14, P21 and P28. 5–10 brains were dissected per biological replicate. Brains were ground on ice before performing Percoll gradient centrifugation. Microglia were sorted by magnetic separation, flow cytometry, followed by RNA sequencing. b The heat map showing the gene profiling expression in two groups. c Venn diagram of co-regulated DEGs by S-ketamine exposure and different developmental stages. d, e Enriched biological processes d and KEGG pathways e of co-regulated 176 DEGs. f Volcano plots for Arg1 on P14, P21 and P28. Red represents relative increased expression and blue indicates relative decreased expression. g qRT-PCR validation of Arg1 in different developmental stages. n = 4 independent experiments. h Schematic of neuron-microglia co-culture. i–l Levels of Arg1 i, CD68 j, CD11b k and CD18 l mRNA in primary microglia cultured solely or co-cultured with neurons after S-ketamine exposure. n = 5 independent experiments. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistical information.

Besides, a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network of these 176 DEGs revealed that Stat1, closely correlated to Arg1 expression, differentially transcribed on P14, P21 and P28 between the control and S-ketamine-exposed mice (Supplementary Fig. 17a). Moreover, Stat1 was included in NOD-like receptor signaling pathway which contained the most DEGs among 176 DEGs (Fig. 4e). The mRNA levels of Arg1 detected by qRT-RCR (P14, P < 0.05; P21, P < 0.001; P28, P < 0.001, Fig. 4g) were consistent with the sequencing results (Fig. 4f). The mRNA levels of Stat1 in microglia from two groups were also confirmed (P14, P < 0.01; P21, P < 0.001; P28, P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 17b). To verify the functional relationship between Stat1 and Arg1, we performed ChIP assay and found that Stat1 was the transcription factor of Arg1, as they had markedly effective binding sites (Supplementary Fig. 17c). In addition, the mRNA and protein level of Arg1 were markedly down-regulated by Stat1 knockdown (si-Stat1-1 had the highest knockdown efficiency) (P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 17d), while up-regulated by Stat1 overexpression (P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 17e, f). To explore whether S-ketamine-induced neuronal abnormalities was mediated by microglia, we performed the co-culture model of primary microglia and neuron in vitro, which was established by transwell (Fig. 4h). Results indicated significantly increased mRNA levels of Arg1, CD11b and CD18 after S-ketamine exposure when microglia were cultured solely or co-cultured with neurons (Arg1, F(1, 16) = 1.572, P = 0.2279; CD11b, F(1, 16) = 6.997, P < 0.05; CD18, F(1, 16) = 0.375, P < 0.05, Fig. 4i, k, l). However, there was no difference between the mRNA levels of CD68 in microglia from saline and S-ketamine groups (Fig. 4j). Compared with microglia cultured solely, microglia co-cultured with neurons showed higher mRNA levels of Arg1, CD68 and CR3, suggesting microglia exerted stronger function of dendritic phagocytosis (Fig. 4i–l). Together, these findings indicate that the Arg1 signaling is involved in S-ketamine-induced microglial activation and enhanced synaptic pruning in postnatal development.

Upregulation of Arg1 in microglia mediates excessive synaptic pruning and abnormal social behaviors

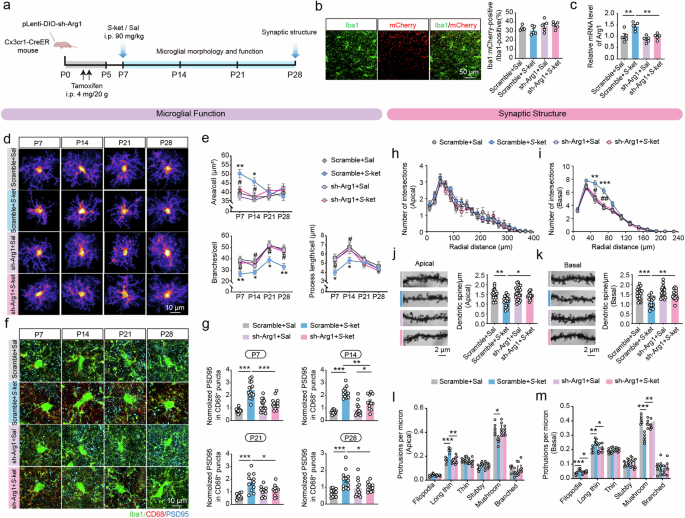

To explore the role of Arg1 signaling in S-ketamine-induced microglial activation, Arg1 was downregulated via intracerebroventricular injection of pLenti-CMV-DIO-mCherry-sh-Arg1 (pLenti-DIO-sh-Arg1) into Cx3cr1-CreER mice on P0, tamoxifen was administered twice between P0 and P5 (Fig. 5a) [46]. Seven days after lentivirus transduction, we observed selective and efficient expression of mCherry in PFC Iba+ microglia (Fig. 5b). The decreased mRNA level of Arg1 in the PFC was verified by qPCR (F(1, 16) = 3.997, P = 0.0629, Fig. 5c). Then, we assessed the PFC microglial morphology and function from P7 to P28. As expected, the microglial activation in S-ketamine-exposed mice treated with pLenti-DIO-sh-Arg1 was greatly inhibited (Fig. 5d), as the soma area of microglia obviously decreased from P7 to P14 (P7, F(1, 47) = 3.002, P = 0.0897; P14, F(1, 45) = 2.818, P = 0.1001), the branch quantities increased from P7 to P28 (P7, F(1, 47) = 5.309, P < 0.05; P14, F(1, 45) = 8.648, P < 0.01; P21, F(1, 51) = 3.441, P = 0.0694; P28, F(1, 58) = 5.361, P < 0.05), and the process length extended from P7 to P14 (P7, F(1, 47) = 4.674, P < 0.05; P14, F(1, 45) = 5.649, P < 0.05, Fig. 5e), in comparison with microglia of S-ketamine-exposed mice. Based on inhibition of microglial hyperactivity, the capability of microglial synaptic pruning was markedly reversed from P7 to P28 (P7, F(1, 56) = 36.82, P < 0.001; P14, F(1, 44) = 13.56, P < 0.001; P21, F(1, 40) = 13.07, P < 0.001; P28, F(1, 44) = 9.000, P < 0.01, Fig. 5f, g), which was also displayed by 3D reconstructed images (Supplementary Fig. 18). There was also significant difference in PSD95 immunoreactivity inside CD68+ lysosomes between saline mice and S-ketamine-exposed mice on P14 after neonatal pLenti-DIO-sh-Arg1 administration (Fig. 5g).

a Schematic diagram of intracerebroventricular bilateral virus infusion and functional tests. b Representative images of mCherry signals co-expressed with sh-Arg1 (left) and the proportions of mCherry-positive cells (right) in Iba1+ microglia in the PFC of Cx3cr1-CreER mice. Scale bar: 50 μm. c qRT-PCR validation of Arg1 mRNA levels in the PFC of different groups after lentivirus transduction and S-ketamine exposure. n = 5 independent experiments. d Heatmaps of overlapped microglia in the PFC of Cx3cr1-CreER mice infected with lentivirus in saline and S-ketamine groups in different developmental stages. Scale bar: 10 μm. e Quantification of microglial soma size (top), branch numbers (bottom left) and average process length (bottom right) in the PFC. n = 3 mice per group, average of 4–8 cells from each mouse. f Representative confocal images of Iba1 (green), CD68 (red), PSD95 (blue) in the PFC. Scale bar: 10 μm. g Quantification of PSD95+ area in CD68+ puncta in the PFC of four groups in different developmental stages. n = 3 mice per group, average of 4–7 cells from each mouse. h, i Sholl analysis of branch complexity in apical h and basal dendrites i on P28. Scramble+Sal, n = 10 neurons, Scramble+S-ket, n = 10 neurons, sh-Arg1+Sal, n = 11 neurons, sh-Arg1+S-ket, n = 10 neurons. j, k Sample images of dendritic branches (left) and quantification (right) of apical j and basal spine density k. Scramble+Sal, n = 20 dendrite segments, Scramble+S-ket, n = 17 dendrite segments, sh-Arg1+Sal, n = 23 dendrite segments, sh-Arg1+S-ket, n = 15 dendrite segments. Scale bar: 2 μm. l, m Proportion of different-typed spines in apical l and basal dendrites m. Data in (h to m) are from 5 mice per group. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001(Scramble+Sal vs Scramble+S-ket); #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 (Scramble+S-ket vs sh-Arg1+S-ket). See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistical information.

Furthermore, the disrupted dendritic structure caused by S-ketamine was apparently normalized via Arg1 downregulation. The branch complexity of basal but not apical dendrites of PFC neurons was greatly decreased in S-ketamine-exposed mice treated with pLenti-DIO-sh-Arg1 (basal: F(33, 407) = 5.384, P < 0.001, Fig. 5h, i), along with increased apical and basal dendrite spines (apical: F(1, 71) = 2.148, P = 0.1472; basal: F(1, 71) = 4.412, P < 0.05, Fig. 5j, k). The maturation of dendrite spines was also notably restored by Arg1 downregulation, which decreased the ratio of long thin spines in apical dendrites (F(1, 16) = 7.490, P < 0.05, Fig. 5l) and filopodia/long thin spines in basal dendrites (filopodia, F(1, 16) = 9.76, P < 0.01; long thin, F(1, 16) = 5.724, P < 0.05, Fig. 5l, m), and increased the ratio of mushroom spines in the basal dendrites (F(1, 16) = 16.29, P < 0.01, Fig. 5m). Finally, we examined whether the social performance was affected by Arg1 downregulation. In three-chamber test, S-ketamine-exposed mice treated with pLenti-DIO-sh-Arg1 preferred the stranger mouse to the object in sociability test (chamber time, P < 0.01; sniffing time, P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 19a, b), and preferred the novel mouse to the familiar mouse in the social memory test (chamber time, P < 0.01; sniffing time, P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 19c, d). In reciprocal social interaction test, similar results were obtained upon pLenti-DIO-sh-Arg1 injection, as these mice spending more time interacting with novel mouse (F(6, 72) = 6.002, P < 0.001, Supplementary Fig. 19e). Likewise, S-ketamine-exposed mice showed elevated social memory index after Arg1 downregulation (F(1, 36) = 8.556, P < 0.01, Supplementary Fig. 19f). Taken together, these findings indicate that specific downregulation of Arg1 in microglia is sufficient to suppress microglial hyperactivation induced by S-ketamine, with reduced synaptic pruning, thus contributing to restoration of neuronal dendrites and social deficits.

Nor-NOHA restored microglial and synaptic functions for preventing social deficits induced by S-ketamine exposure

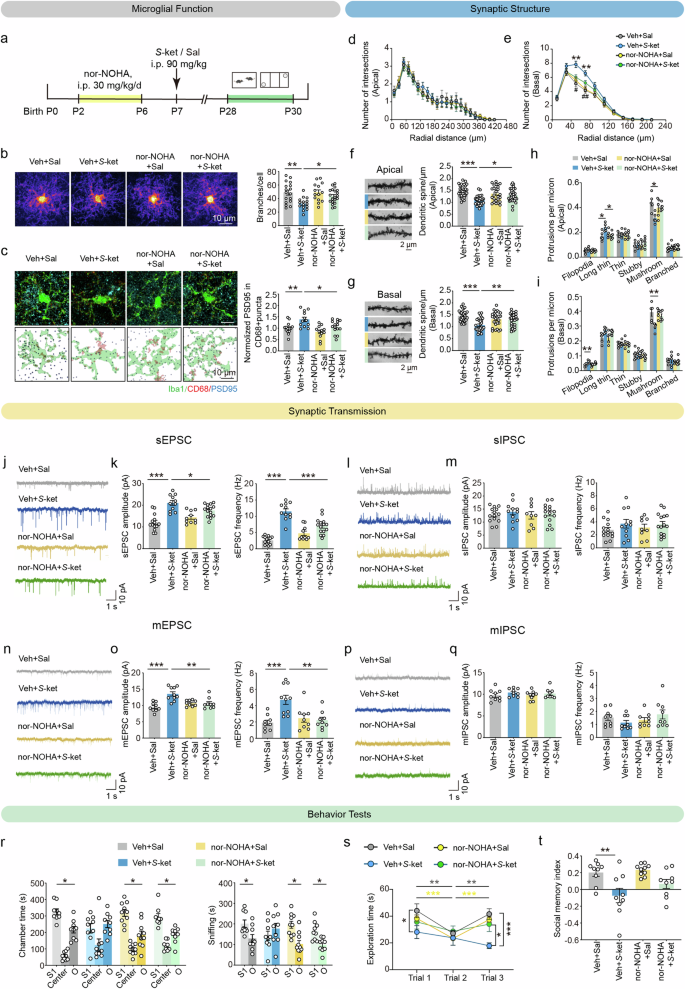

The effects of nor-NOHA, a selective arginase inhibitor, were also explored. Neonatal C57 mice were injected with nor-NOHA (30 mg/kg) daily from P2 to P6 before S-ketamine injection on P7 (Fig. 6a). The overlaid heatmaps showed that nor-NOHA restored the branch number of microglia in the PFC of S-ketamine-exposed mice (F(1, 62) = 3.688, P = 0.0594, Fig. 6b). Likewise, increased PSD95 immunoreactivity inside CD68+ lysosomes in the PFC microglia of S-ketamine-exposed mice were reversed by nor-NOHA on P28 (F(1, 49) = 1.184, P = 0.2818, Fig. 6c). In addition, nor-NOHA reduced the complexity of basal but not apical dendrites of PFC pyramidal neurons induced by S-ketamine exposure (basal: F(30, 370) = 4.197, P < 0.001, Fig. 6d, e), accompanied by increased apical (F(1, 113) = 9.943, P < 0.01, Fig. 6f) and basal dendrite spines (F(1, 113) = 13.81, P < 0.001, Fig. 6g), decreased ratio of long thin spines in the apical but not basal dendrites (F(1, 16) = 7.799, P < 0.05, Fig. 6h, i). Moreover, the redundant amplitudes and frequencies of sEPSC (amplitude: F(1, 46) = 9.537, P < 0.01; frequency: F(1, 46) = 29.79, P < 0.001, Fig. 6j, k) and mEPSC (amplitude: F(1, 33) = 15.36, P < 0.001; F(1, 33) = 11.58, P < 0.01, Fig. 6n, o) in the pyramidal neurons of PFC were downregulated by nor-NOHA administration, whereas no effect on sIPSC (Fig. 6l, m) and mIPSC (Fig. 6p, q).

a Schematic diagram of nor-NOHA treatment and behavior tests. b Heatmaps of overlapped microglia (left) and quantification of microglial branch numbers (right) in the PFC on P28. Scale bar: 10 μm. n = 3 mice per group, average of 4–8 cells from each mouse. c Representative confocal images (left top) and 3D reconstructed images (left bottom) of Iba1 (green), CD68 (red), PSD95 (blue) and quantification of PSD95+ area in CD68+ puncta (right) in the PFC of four groups on P28. Scale bar: 10 μm. n = 3 mice per group, average of 4–7 cells from each mouse. d, e Sholl analysis of branch complexity in apical d and basal dendrites e on P28. Veh+Sal, n = 10 neurons, Veh+S-ket, n = 10 neurons, nor-NOHA+Sal, n = 9 neurons, nor-NOHA + S-ket, n = 12 neurons. f, g Sample images of dendritic branches (left) and quantification (right) of apical f and basal spine density g. Veh+Sal, n = 31 dendrite segments, Veh+S-ket, n = 28 dendrite segments, nor-NOHA+Sal, n = 26 dendrite segments, nor-NOHA + S-ket, n = 32 dendrite segments. Scale bar: 2 μm. h, i Proportion of different-typed spines in apical h and basal dendrites i. Data in (d to i) are from 5 mice per group. j–m Representative traces, amplitudes (left) and frequencies (right) of sEPSC j, k and sEPSC l, m from the pyramidal neurons in the PFC. k Veh+Sal, n = 14 neurons, Veh+S-ket, n = 11 neurons, nor-NOHA+Sal, n = 10 neurons, nor-NOHA + S-ket, n = 15 neurons. m Veh+Sal, n = 14 neurons, Veh+S-ket, n = 11 neurons, nor-NOHA+Sal, n = 9 neurons, nor-NOHA + S-ket, n = 15 neurons. n–q Representative traces, amplitudes (left) and frequencies (right) of mEPSC n, o and mIPSC p, q from the pyramidal neurons in the PFC. o Veh+Sal, n = 9 neurons, Veh+S-ket, n = 10 neurons, nor-NOHA+Sal, n = 9 neurons, nor-NOHA + S-ket, n = 9 neurons. q n = 9 neurons per group. Data in j–q are from 3 mice per group. r Time spent in each chamber (left) and close interaction (right) with O and S1 in the sociability test of three-chamber test. s, t Social exploration time (s) and social memory index t in the direct interaction of mice from four groups. Veh+Sal, n = 9, Veh+S-ket, n = 9, nor-NOHA+Sal, n = 10, nor-NOHA + S-ket, n = 9. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (Veh+Sal vs Veh+S-ket); #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 (Veh+S-ket vs nor-NOHA + S-ket). See Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistical information.

Besides, nor-NOHA remarkably increased the duration spent in the chamber with the stranger mouse (P < 0.05), as well as sniffing time with the stranger mouse in the sociability test of three-chamber social paradigm (P < 0.05, Fig. 6r). Nor-NOHA also alleviated the impaired social memory of S-ketamine-exposed mice, as they showed more preference towards the novel mouse than the familiar mouse in the social memory test (chamber time, P < 0.05; sniffing time, P < 0.05, Supplementary Fig. 20a, b), and more exploration time of reciprocal social interactions with novel mouse in homecage (F(6, 66) = 3.814, P < 0.01, Fig. 6s), without significant elevation in the social memory index (F(1, 33) = 0.9443, P = 0.3382, Fig. 6t). These results collectively suggest that nor-NOHA reverses S-ketamine-induced abnormal neuronal morphology via inhibiting elevated microglial activation and synaptic engulfment in the PFC, ultimately contributing to normalization of social behaviors.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that S-ketamine exposure in mice at early postnatal period induced significant social cognitive impairments during adolescence, including deficits in sociability and social memory, which were not accompanied by working memory deficits and other ASD symptoms, such as stereotyped behaviors, motor dysfunctions, and damages in reversal memory. These compromised social deficits were attributed to impaired excitatory synaptic transmission, which was mediated by excessive microglial synaptic pruning in the PFC. Additionally, microglia in the PFC exhibited high expression of Arg1 following S-ketamine exposure. The specific downregulation of Arg1 in microglia and pretreatment with the Arg1 inhibitor nor-NOHA could restrict the overactivation of microglia and suppress the capacity of microglial synaptic pruning and normalize the dendritic complexity of pyramidal neurons in the PFC, thereby restoring the performance of social interaction during adolescence. These results illustrated that the disrupted dendritic complexity during neurodevelopment, which was mediated by dysfunction of microglial synaptic pruning, represented a critical mechanism of neural developmental anomalies induced by S-ketamine exposure at early postnatal period.

In accordance with previous findings in children and NHPs exposed to general anesthesia during the neonatal period, S-ketamine exposure at early postnatal period preferred to induce social deficits rather than cognitive decline in adolescent mice. Evidence from clinical trials have demonstrated that general anesthesia at early childhood was the high-risk factor of lower social linguistic function, instead of other symptoms of neurocognitive deficits [13]. Besides, studies on juvenile NHPs also reported that isoflurane exposure to infant would impair close social behavior but not cognitive domains, including spatial working memory, executive function or cognitive flexibility [7, 47]. Particularly, the abnormal social cognition could not be induced by subanesthetic dose exposure of S-ketamine at early postnatal period, as well as anesthetic dose exposure in adulthood. We speculated that this age- and dose- dependence might be attributed to the higher reactiveness of neurocytes to changes in exocellular environment during neurodevelopment period.

Although the principle of social memory should not be simply divided into the superposition of sociability and working memory [48], we speculated that the social memory impairments detected by three-chamber test resulted from the aberrant sociability displayed in this study. Consequently, we utilized the novel machine learning-assisted toolbox of SBeA, and categorized the social interactions of mice into seven distinct clusters. The findings demonstrated that mice exposed to S-ketamine displayed a proclivity to disregard the actions of their conspecifics and exhibited a reduction in affiliative interactions with familiar individuals. Furthermore, they exhibited pronounced avoidance and defensive behaviors when confronted with strange individuals, indicating a generalized aversion to social interactions. According to Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS), which is widely used to diagnose ASD, these social behaviors in mice could be reclassified into four categories for closer interpretation to the clinical phenotype [49]. S-ketamine group mice exhibited significantly lower social motivation (more ignorance), social awareness (submissive and defensive behavior) and social communication (approaching and affiliative behavior), without alteration in social cognition (searching and investigation) when interacting with familiar mice. As interacting with stranger mice, S-ketamine group mice also performed higher fractions of social awareness and less fractions of social cognition and social communication. These phenotypes were similar to the symptom of children with social disabilities: difficulty responding positively to intimate people such as parents, and avoiding communication with unfamiliar people. Moreover, mice exposed to S-ketamine showed increased rates of grooming and rising/jumping movements, while exhibiting decreased rates of exploration in locomotion. Given that the core symptoms of ASD encompass social deficits and stereotyped behaviors, we also investigated whether S-ketamine-exposed mice exhibited alterations in repetitive stereotyped motions and whether these were accompanied by anxiety and aberrant cognitive flexibility [12]. To this end, we performed marble burying experiment and sequential self-grooming, and revealed that such cognitive dimensions were not impaired. As for different sorts of general anesthetics, such as sevoflurane, cannot induce social deficit. The results provided a more accurate and refined behavioral identifications of the effects of S-ketamine exposure at the early postnatal period on the neurocognitive development. Our findings suggested that the aberrant phenotype induced by S-ketamine exposure differed from that observed in other developmental disorders with social deficits as major symptom.

Social cognition is contingent upon the normal neuronal excitability and synaptic plasticity in the neocortex, hippocampus, and other higher-order brain regions. Actually, the causal support for the elevated cellular E/I balance hypothesis in PFC excitatory neurons underlying disrupted information processing and social dysfunction has been illustrated [14]. For instance, the variant ArpC3 gene in mice significantly increased excitatory synaptic transmission and therefore disrupted E/I balance of the pyramidal neurons within the PFC and downstream circuit, mediating impaired performance in social affiliation test [50]. Particularly, the normal structure of synapses is an essential substrate for maintaining E/I balance in neurons. The abnormal synaptic pruning and dendritic structures have been observed in human patients and multiple animal models with social cognitive impairment [51, 52]. In line with previous findings, we noticed abnormal dendritic structures of pyramidal neurons in the PFC after S-ketamine exposure, including increased dendritic complexity but decreased density of dendritic spines, and a lower ratio of mushroom spines but a higher ratio of immature spines. The structural plasticity of dendrites is important for synaptic transmission, particularly for the maintenance of neuronal E/I balance [53]. One possibility of enhanced excitatory neurotransmission is that neurons that undergo excessive synaptic pruning develop microscopic synaptic structures in which axonal nodules bind multiple dendritic spines [54, 55]. Therefore, reduced spine density might lead to more efficient or stronger synapses on the remaining spines, enhancing neurotransmitter release probability or receptor sensitivity at existing synapses [56].

As a psychoactive substance, ketamine has been reported to result in persistent change of E/I balance in cortical synaptic activity, and increase the overall excitability of the mPFC [57]. In current study, we found that the frequencies and amplitudes of sEPSC in PFC pyramidal neurons increased without alteration of sIPSC after S-ketamine exposure. It implied that the influence of S-ketamine exposure on neurotransmission might be sustained and selective to excitatory synapses. Differed from other general anesthetics targeting to GABA receptors, such as propofol and etomidate, S-ketamine, an enantiomer of (R, S)-ketamine, exhibits a stronger affinity for N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptors (NMDARs) [58]. Overactivation of excitatory synaptic transmission was closely linked to compromised social behaviors in ASD as well. For example, CUL3 or CDKL5 deficiency resulted in enhanced excitatory neurotransmission and induced dissociation [57, 59]. The frequency of mEPSC and synaptosomal protein as VGluT1 and Syntaxin (STX) 18 were markedly increased in 59fl/fl;Lyz2 mice [59]. Therefore, we considered that the overactivated excitatory synaptic transmission may potentially alter the signal-to-noise ratio (excitatory noise), which could result in impaired social information processing [60]. In other words, it also indicated that the abnormal sociability induced by S-ketamine might share a similar mechanism of abnormal dendritic development with ASD individuals.

Microglia are instrumental in the process of synaptic refinement throughout postnatal development [61]. In a resting state, microglia are highly ramified with small soma and interspersed protrusions [62]. In the event of a significant alteration in the extracellular microenvironment, microglia would become activated and migrate towards the site of infection or injury. This ultimately results in the transformation of microglia into ameboid cells with minimal and short protrusions, which in turn triggers a multitude of functions, including phagocytosis [63]. The structure of microglia undergoes dynamic remodeling throughout the early postnatal period, manifesting as a gradual transformation from an ameboid to a primarily branched state at approximately 1–2 weeks after birth and reaching maturity around P28 [64]. In the present study, we observed that microglia exhibited pronounced activation, characterized by enlarged soma, retracted branches, and shortened processes, following exposure to S-ketamine. Concurrently, S-ketamine exposure augmented microglial contacts with dendrites and microglial phagocytosis of spines during development, as evaluated by PSD95 co-localization with CD68. Furthermore, mRNA levels of CR3 and CD68 in microglia were also significantly increased after S-ketamine exposure, indicating that the complement system was activated to mediate the engulfment of synapses [51, 65] and the phagocytosis of excitatory synapses [66]. The complement system is a component of the innate immune system that plays a pivotal role in microglial function, including synaptic pruning, debris removal, and neuroinflammatory regulation. Within a pathological condition, the activated complement pathway prompted microglia to engulf normal synapses, resulting in synaptic loss. It was demonstrated that a deficiency in the C3-CR3 signaling pathway resulted in a reduction in microglial phagocytosis of apoptotic photoreceptor cells [67]. Inhibition of the complement C3-CR3 pathway was observed to improve microglia-mediated abnormal synaptic pruning, and subsequently, to enhance the antidepressant-like effects in mice underwent chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) [68]. These findings indicated that S-ketamine induced a morphological differentiation in microglia and intensified synaptic pruning, which could potentially result in damage to the dendritic structure of pyramidal neurons during adolescence. Additionally, our findings revealed that these variations were more pronounced and prolonged in the PFC compared to hippocampal CA2, suggesting that the PFC exhibited hypersensitivity to S-ketamine during the early postnatal period.

The S-ketamine-modulated genes of microglia were further explored by RNA sequencing. The enrichment analysis of GO terms revealed significant variations in the defense response to external stimuli, and KEGG pathway analysis highlighted enrichment in immune response and microglial activity. The PPI network revealed a tight correlation between Arg1, which is involved in arginine biosynthesis, and Stat1, a major transcription factor of Arg1 that is differentially expressed on P14, P21, and P28. Specifically, based on the enrichment analysis of DEGs, it is speculated that NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, Toll-like receptor signaling pathway and biological processes such as inflammatory response are involved in the activation of Stat1-Arg1 pathway in microglia [69]. Arginase 1 (Arg1) is an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of L-arginine to ornithine and urea [70]. Recent studies have demonstrated that Arg1+ microglia in the basal forebrain regulate postnatal development and neurocognition by modulating cholinergic innervations and affecting dendrite maturation in the hippocampus [71]. The reduction in Arg 1 expression led to a reduction in dendritic complexity, intrinsic excitability, and modified synaptic transmission in layer 5 motor cortical neurons [72]. Here, we demonstrated that specific downregulation of Arg1 in microglia significantly inhibited sustained microglial activation, reduced phagocytosis of excitatory synapses, and rescued the synaptic structures of pyramidal neurons in the PFC, thereby normalizing social behaviors. Moreover, the preventive administration of nor-NOHA, a selective arginase inhibitor, also modified the branch complexity of microglia, restored the synaptic structures and neurotransmission of pyramidal neurons in the PFC, and alleviated social deficits. However, this intervention was applied systemically, which precludes the possibility of excluding the direct modulatory effect of nor-NOHA on neurons. In clinic, nor-NOHA has been utilized in the treatment of cerebral ischemia and acute kidney injury [73, 74]. Its effectiveness and safety for use in infants and young children have yet to be verified. Of note, this activation of microglia and elevated expression of Arg1+ were not temporary but endured to adolescence. We speculated that the sustained activation of microglia may be related with variations in several biological process modulated by S-ketamine exposure. The results of proteomics showed a notable variation enriched in biological processes associated with neuroinflammation and neuroimmunity from P7 to P28 (Supplementary Fig. 21). Specifically, S-ketamine exposure immediately induced the acute inflammatory response in the PFC on P7. Then, the production and recruitment of inflammatory cytokines, the assembly of inflammasome complex, and innate immune response were subsequently occurring in the PFC until P28, which potentially mediated lasting functional and morphological changes in microglia.

However, the discrepancy between the social behaviors in mice and human should be noted. Human social interactions often involve intricate language, emotional exchanges, facial expressions and tonal variation, and are influenced by higher-order cognitive processes, such as theory of mind and empathy, which are not fully replicable in rodents. Besides, human social interactions are affected by diverse environments and contexts, whereas rodent models are limited to controlled laboratory settings. Therefore, when applying our findings to explain the mechanisms of human social behavior disorders, interspecies differences need further investigations.

Overall, this study elucidated a molecular mechanism that general anesthesia by S-ketamine during early postnatal period induces social behavioral deficits, mediated by microglial dysfunction. This provides novel insight into the usage of S-ketamine in infant and young children and uncovers a possible target for the prevention of neurodevelopmental disorders with social symptoms like ASD.

Responses