Safety and immunogenicity in humans of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli double mutant heat-labile toxin administered intradermally

Introduction

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) is a leading bacterial cause of diarrhea. It is responsible for a large burden of disease globally, affecting primarily young children living in poor-resource settings, soldiers deployed to endemic regions, and travelers1,2. The absence of a licensed vaccine compels efforts to identify safe and effective prevention and control measures. Vaccine candidates targeting the ETEC heat-labile enterotoxin (LT), a major virulence factor, along with other adhesin antigens, are among the most advanced in clinical evaluation2,3. Recent data indicates that LT alters the structure and function of the intestinal epithelium, which may underlie both the acute and long-term negative health outcomes associated with ETEC infection among infants and young children in low- and middle-income countries4. In addition, LT has the potential to modulate receptor expression in the intestine, as well as multiple other aspects of gut physiology that render infected individuals more susceptible to other enteric pathogens5,6,7. Consequently, the induction of robust immunity against this virulence factor will enhance ETEC vaccine efficacy. The potential of detoxified forms of LT to serve as a standalone ETEC vaccine requires further evaluation. Earlier studies with an oral cholera vaccine supplemented with the B-subunit of cholera toxin (CTB), a toxoid that induces cross reacting antibodies to LT, showed protection against ETEC diarrhea associated with strains expressing LT alone or in combination with the ST toxin8,9. In these studies, the anti-CTB antibody response was interpreted as the basis for the ETEC protection observed. In more recent studies, the native LT toxin delivered by transcutaneous patch was evaluated as a standalone vaccine for ETEC-associated travelers’ diarrhea (TD) in two field trials10,11. The protective efficacy of the LT patch against moderate to severe ETEC diarrhea in these trials was limited, while protection against all cause diarrhea was variable. An interesting and potentially important public health observation from both trials was that LT patch recipients experiencing TD episodes had significantly fewer diarrhea stools and TD episodes of shorter duration than placebo patch recipients, independent of etiology. The potential for LT immunization to reduce diarrhea severity was also observed in an ETEC controlled human infection model (CHIM)12. The potential broader public health benefits of effective LT immunization on overall diarrhea documented in these studies warrant further investigation as a potential basis for the value proposition of including LT as an antigen in future enteric vaccines. The limited and variable protective effect of LT immunization against ETEC toxin types also deserves further assessment because alternative parenteral routes of vaccine delivery, like intradermal (ID) or intramuscular (IM), may yield more consistent dosing, and thus more consistent protection than was possible using early patch-based technology applied to the skin. Pursuing these alternative routes of delivery for LT has been prevented by the reactogenic/enterotoxic properties of native LT. However, the interest in further evaluating LT as both a vaccine antigen and adjuvant has driven efforts to create detoxified variants, thus broadening the option for delivery.

A double mutant LT (LTR192G/L211A, dmLT) was created by sequential introduction of point mutations that disrupted enzymatic and toxigenic activity13. It has been proposed that dmLT could serve as a stand-alone vaccine, as well as a mucosal adjuvant for other co-administered vaccine antigens13. Oral and sublingual administration of dmLT in doses up to 100 µg and 50 µg14, respectively, were shown to be safe, although modestly immunogenic. While these routes would be practical and ideal to elicit local protective immunity, responses were low and variable. Successful delivery of protein-based vaccines, like dmLT, via the oral route is hindered by the hostile gut environment and the need for large doses or methods to improve bioavailability and immunogenicity. Hence, other routes of delivery have been investigated.

The intradermal (ID) route has been proposed as an alternative for an ETEC vaccine based on successes reported with other vaccines, including Hepatitis A, seasonal Influenza, Polio, Hepatitis B, ETEC, COVID, Rabies, and Measles15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Intradermal vaccination is known to engender superior immunity using a fractional dose of vaccine antigen. The CfaE tip adhesin of ETEC was evaluated as a vaccine antigen given intradermally with an attenuated single mutant LT (LTR192G); this study demonstrated robust immune responses to CfaE and LT, and mLT adjuvant effect16. In addition, immunization with the CfaE and mLT reduced moderate-severe diarrhea rates and overall ETEC disease severity in an ETEC CHIM study24. A preceding study investigated the safety and immunogenicity of an ID fractional dose of inactivated polio vaccine (fIPV) adjuvanted with dmLT and showed the capacity of dmLT to enhance systemic IPV immunity25 and an ongoing phase 1 study is evaluating the efficacy of dmLT-adjuvanted fIPV against monovalent poliovirus challenge (NCT05327426). A phase 1 study of transcutaneous delivery of dmLT as an adjuvant of a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) vaccine candidate is ongoing (NCT04826094). Additionally, clinical studies to evaluate IM administration of dmLT as an ETEC vaccine component along with CS6 (NCT06692907), or as an adjuvant for ETEC26, poliovirus27, and Shigella vaccine candidates (NCT05961059) are about to start, ongoing, or have recently been completed.

Considering the practicality and potential cost-effectiveness of the ID route for vaccine delivery, we conducted a Phase 1 study to investigate the safety and immunogenicity of ascending doses of dmLT given by the ID route to healthy adult subjects. Here, we report clinical tolerability and induction of serum and mucosal immune responses in cohorts receiving single or multiple immunizations. This study begins to address an important knowledge gap in the vaccine and adjuvant fields to understand the tolerability and immunogenic properties of dmLT given parenterally. While dmLT is known to be well tolerated and immunogenic, and a potent adjuvant when given to both adults and infants by the oral route16,24,25,26,28,29,30, the evaluation of dmLT given parenterally as an ETEC antigen or vaccine adjuvant has been limited, with doses above 0.5 μg never been assessed.

Results

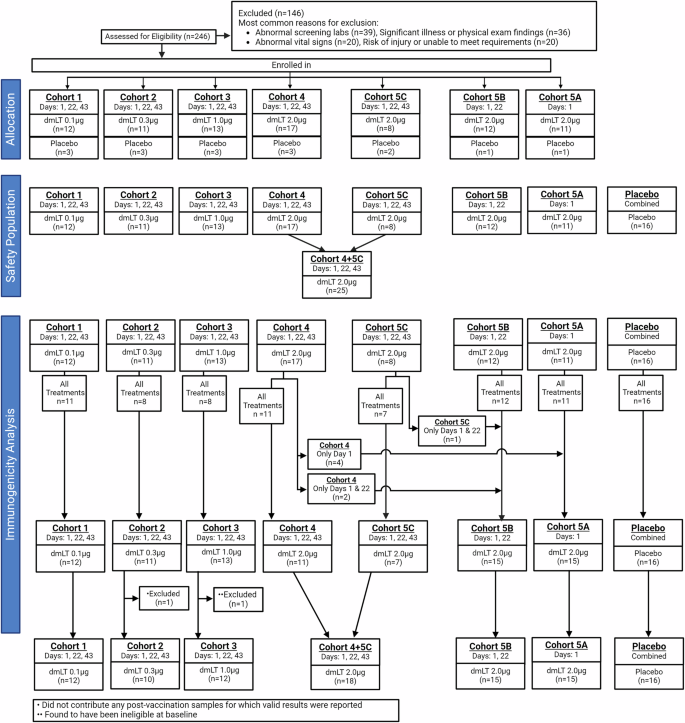

One hundred subjects were enrolled and randomized to one of five cohorts to receive dmLT in increasing dosage levels (0.1, 0.3, 1.0, and 2.0 µg) or placebo in single or multiple immunizations (Fig. 1). The demographics for all subjects enrolled showed no differences in gender, ethnicity, race, and age among cohorts (Table 1).

Of the original 246 participants screened, 100 were enrolled in seven cohorts to receive increasing dosages of dmLT ID (Cohorts 1-4), placebo, or in one to three vaccinations of highest tolerable dose, 2.0 µg of dmLT (Cohorts 5A-C).

All participants in each cohort received the first immunization, and between 62 and 100% received all immunizations corresponding to either treatment or placebo. Regardless of the number of doses received, retention through six months follow up post-last vaccination ranged from 82 to 100%, except for Cohort 5 C, for which 63% (5/8) of subjects remained.

Safety

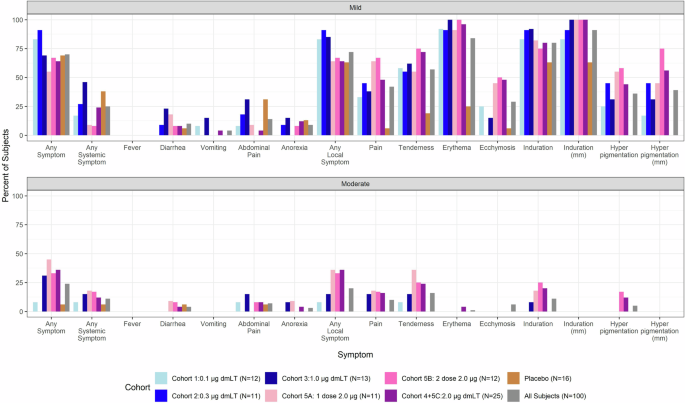

The vaccine was found to be safe at all doses evaluated. Solicited adverse events (AEs) were common but mostly mild, with no severe symptoms reported (Fig. 2). Among all 100 subjects, 92 (92%) experienced at least one local injection site solicited mild or moderate AE, and 36 (36%) experienced at least one systemic solicited mild or moderate AE. The most common local symptom across the entire study population was induration (91%), followed by erythema (85%), tenderness (73%), and pain (52%). The most common systemic events were related to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and included abdominal pain (21%), diarrhea (14%) and anorexia (12%). Those with lower dosages of dmLT (0.1 and 0.3 µg) had fewer occurrences of any moderate symptoms and had no experiences of moderate pain and induration.

Prevalence and severity of solicited symptoms by cohort at any time point after first vaccination.

Of the unsolicited treatment-related AEs, nine (9%) subjects, one of which received the placebo, experienced related unsolicited AEs of moderate severity, and one subject experienced at least one severe related unsolicited AE. There were no safety concerns regarding serum chemistry and hematology analysis following immunization, although minor transient changes were noticed. No serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported for any cohort. Five subjects discontinued study treatments due to AEs (two due to upper respiratory infection and one each due to influenza-like illness, gum infection, and elevated diastolic blood pressure), all of which were unrelated to the vaccine.

Of interest was the occurrence of hyperpigmentation at the injection site in dmLT recipients (Supplementary Table 1). These unusual lesions were lacking in the placebo cohort while somewhat dose-dependent in the vaccinated cohorts, as they occurred in 33% of participants receiving the lowest dose (0.1 µg), 64% at 0.3 µg, 69% at 1.0 µg, and 94% at 2.0 µg (across all participants receiving at least one vaccination at this dose level). Additionally, hyperpigmentation developed after any of the three vaccination time points, with those that experience hyperpigmentation after the first vaccination often experiencing it again after the second or third doses. The lesions persisted for an extended period, depending on dosage level (mean 97.5 days at 0.1 µg and ~175.8 days at a dosage of 2.0 µg). The lesions did not induce symptoms, so the concern was purely cosmetic.

Antibody responses

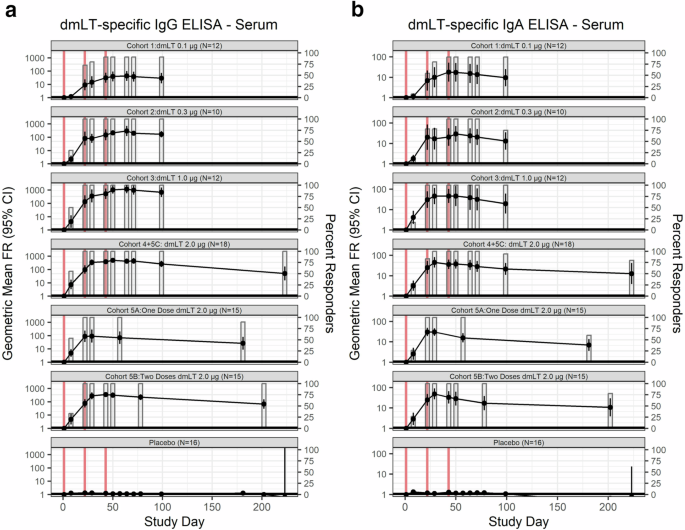

All dmLT cohorts, except for the 0.1 µg dose (Cohort 1), attained complete (all individuals in the cohort) IgG seroconversion 21 days after the first vaccination (0.3 µg n = 9, 1.0 µg n = 10, 2.0 µg one dose n = 12, 2.0 µg two doses n = 15, 2.0 µg three doses n = 18) (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. 1A-B). Compete IgA seroconversion was attained in all cohorts receiving at least 1.0 µg dmLT seven days after the second vaccination or 28 days after the first vaccination for those receiving a single dose of 2.0 µg dmLT (1.0 µg n = 9, single dose 2.0 µg n = 11, two doses 2.0 µg n = 14, three doses 2.0 µg n = 18). Cohort 2, 0.3 µg of dmLT, attained complete IgA seroconversion (n = 6) 21 days after the second vaccination, while Cohort 1, 0.1 µg of dmLT, reached a maximum IgA and IgG seroconversion of 91% (10/11) 21 days after the second vaccination.

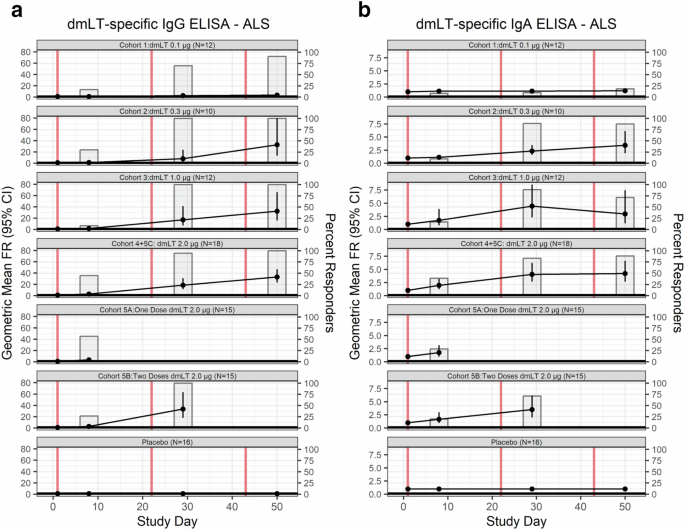

a Immunoglobulin (Ig) G and (b) IgA antibody responses in serum to dmLT in vaccinees and placebo by dosage of dmLT and number of vaccinations (represented by the vertical red lines). GMFR are represented by line while the percentage of responders (FR ≥ 4) is represented by bar plots. Subjects who received 2.0 µg of dmLT were classified based on number of vaccinations received, rather than initial randomization.

While the cohort that received 1.0 µg of dmLT (Cohort 3) had the highest geometric mean fold-rise (GMFR) for serum IgG, 673.5 [95% CI: 294.2–1541.9], eight weeks after the final vaccination, it also had a nearly three-fold smaller baseline geometric mean titer (GMT) (55.8, 95% CI: 27.0–115.1) than the group with the next lowest baseline GMT, Cohort 4 + 5 C, which received three doses 2.0 µg (146.2, 95% CI: 81.7–261.6). Eight weeks after final vaccination, those that received three vaccinations of 2.0 µg of dmLT (Cohort 4 + 5 C), had the next highest serum IgG GMFR, 260.6 [95% CI: 153.5–442.3]. Six months from last vaccination (only collected for Cohorts 5A-C), individuals who received two or three doses of 2.0 µg dmLT (Cohorts 5B and 5 C) retained 100% (9/9 and 5/5; Cohorts 5B and 5 C, respectively) IgG seroconversion. In those that received a single 2.0 µg dose of dmLT (Cohort 5 A), IgG seroconversion declined to 90.0% (9/10).

Eight weeks after third vaccination, the serum IgA depicted a dose-dependent response profile, with GMFR of 9.5 [95% CI: 3.6–24.9], 13.0 [95% CI: 4.9–34.7], 19.4 [95% CI: 6.3–59.7], and 21.2 [95% CI: 10.9–41.0], in cohorts receiving 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, and 2.0 µg of dmLT, respectively. Six months from the last vaccination (only collected for Cohorts 5A-C), both the magnitude of serum IgA GMFR and rate of retained seroconversion improved in relation to the number of doses of 2.0 µg of dmLT received; GMFR = 6.9 [95% CI: 3.6–13.4], 10.7 [95% CI: 3.8–29.7], and 12.7 [95% CI: 3.9–41.1], one-, two- and three-vaccinations (Cohort 5 C only) of 2.0 µg dmLT, respectively. Seroconversion rates six months after final vaccination with 2.0 µg dmLT were 60% (6/10), 78% (7/9), and 80% (4/5) in subjects who received one-, two- and three-vaccinations (Cohort 5 C only), respectively.

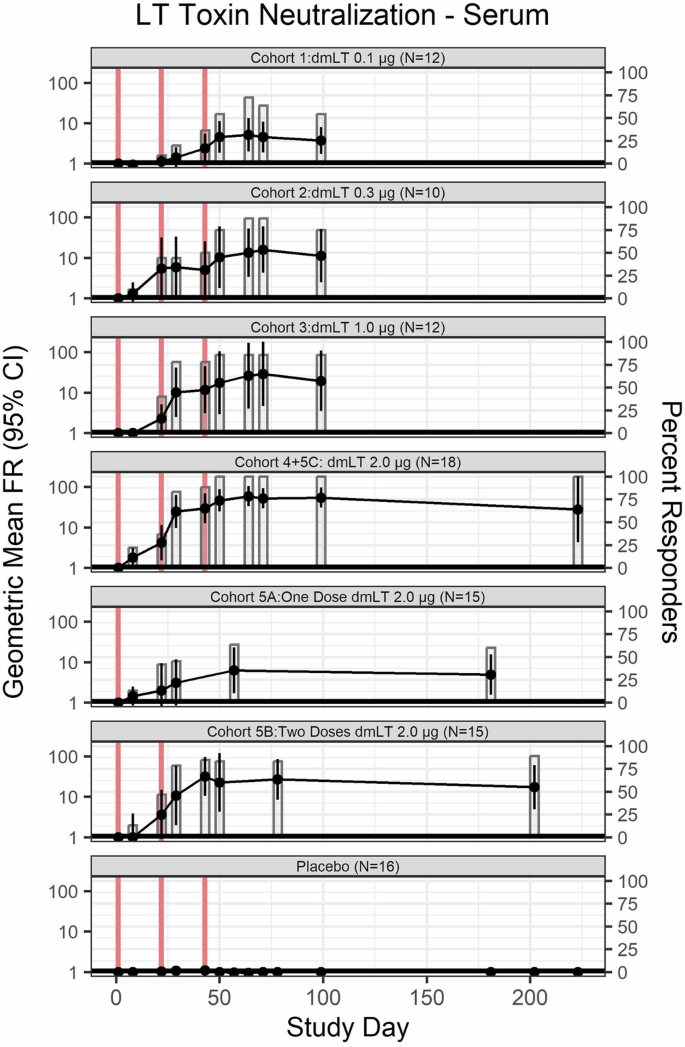

Similarly, LT neutralizing antibodies at eight weeks after the third vaccination depicted dose-dependent response profiles with GMFR of 3.8 [95% CI: 1.8–8.1], 11.3[95% CI: 2.5–51.6], 19.5 [95% CI: 3.5–109.4], and 54.4 [95% CI: 30.7–96.2], in cohorts receiving 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, and 2.0 µg of dmLT, respectively (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. 1C). Only subjects who received three vaccinations of the highest dosage level, 2.0 μg dmLT (Cohort 4 + 5 C), reached 100% (17/17) response rate one week after the third vaccination. Additionally, six months from the final vaccination (only collected for Cohorts 5A–C), both the GMFR of LT neutralizing antibodies and response rate exhibited a dose-dependent trend in recipients of 2.0 µg of dmLT; GMFR = 4.9 [95% CI: 1.6–15.5], 17.3 [95% CI: 4.9–61.1] and 27.9 [95% CI: 4.3–180.0] for one, two, and three vaccinations respectively. Seroconversion rates were 60.0% (6/10), 88.9% (8/9), and 100% (5/5) in subjects who received one, two, and three vaccinations (Cohort 5 C only), respectively.

LT neutralizing antibody in vaccinees and placebo by dosage of dmLT and number of vaccinations (represented by vertical red lines). GMFR are represented by line while the percentages of responders (FR ≥ 4) are represented by bar plots. Subjects who received 2.0 µg of dmLT were classified based on number of vaccinations received, rather than initial randomization.

No seroconversions were detected in the placebos; the maximum GMFR was 1.3 [95% CI: 1.1–1.6], 1.3 [95% CI: 1.1–1.6], and 1.1 [95% CI: 1.0–1.3], for IgG, IgA, and LT neutralizing antibodies, respectively.

We also examined the presence of antibodies in lymphocyte supernatants (ALS) (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 1D–E). ALS IgG response rate reached 100% one week after final vaccination in all cohorts (0.3 µg n = 8, 1.0 µg n = 7, two doses 2.0 µg n = 14, three doses 2.0 µg n = 17), except for the lowest dosage level group, 0.1 µg (Cohort 1) and those who only received one dose of 2.0 µg (Cohort 5 A). Still, Cohort 1 reached a response rate of 91.0% (10/11) after the third vaccination of 0.1 µg of dmLT, while Cohort 5 A reached a response rate of only 57.1% (8/14) after the first and only vaccination. The peak GMFR for ALS IgG occurred after the final vaccination regardless of dose level in those that received three doses of at least 0.3 µg of dmLT. After the third vaccination, those subjects who received 2.0 µg of dmLT (Cohort 4 + 5 C) had the highest ALS IgG GMFR, 32.8 [95% CI: 23.2–46.5], followed closely by those receiving 0.3 and 1.0 µg of dmLT (GMFR: 32.6 [95% CI: 13.4–79.3], and 32.3 [95% CI: 15.8–65.9], respectively).

a Immunoglobulin (Ig) G and b IgA antibody responses in ALS to dmLT in vaccinees and placebo by dosage of dmLT and number of vaccinations (represented by vertical red lines). GMFR are represented by line while the percentages of seroconversion (FR ≥ 2) are represented by bar plots. Subjects who received 2.0 µg of dmLT were classified based on number of vaccinations received, rather than initial randomization.

The ALS IgA were somewhat lower as compared with ALS IgG responses, yet nonetheless robust, with the maximum rate responses occurring in individuals who received three doses of dmLT at either 0.3 (88.9%, 8/9), 1.0 (88.9%, 8/9), or 2.0 µg (88.2%, 15/17) (Fig. 5). The IgA GMFR peaked in participants that received 1.0 µg of dmLT (Cohort 3) after the second vaccination (GMFR: 4.4 [95% CI: 2.3–8.5]). The remaining cohorts peaked after the final vaccination regardless of number of doses received (GMFR = 1.2 [95% CI: 0.9–1.6], GMFR = 3.4 [95% CI: 1.9–6.1], GMFR = 4.2 [95% CI: 2.7–6.6], GMFR = 3.5 [95% CI: 2.0–6.2], GMFR = 1.7 [95% CI: 1.0–3.1], 0.1 µg, 0.3 µg, three doses of 2.0 µg, two doses of 2.0 µg, and one dose of 2.0 µg, respectively).

Lastly, the ratio of dmLT-specific IgA to total IgA mucosal antibodies was measured in stool supernatants (Supplemental Fig. 2). Less than half of the participants (5/12), receiving 0.1 µg of dmLT reached the level of detection (3.0 ng/mL) at any post-vaccination time point, none of whom reached a positive response rate at any time point. The remaining treatment groups had on average 89% of participants above the limit of detection for at least one post-baseline time point; 8/10, 9/12, 11/15, 14/15, and 15/18 for those receiving 0.3, 1.0, and 2.0 µg of dmLT in one-, two- and three-vaccinations, respectively. Of participants with detectable fecal dmLT IgA, approximately half had a positive response at least one time point post vaccination among those who received 0.3 µg of dmLT (Cohort 2; 4/8), one dose of 2.0 µg of dmLT (Cohort 5 A; 6/11), and three doses of 2.0 µg of dmLT (Cohort 4 + 5 C; 8/15). Cohorts 3 (1.0 µg of dmLT) and 5B (two doses of 2.0 µg of dmLT) had lower proportions of participants with a positive fecal response for a least one time point post vaccination: 22% (2/9) and 29% (4/14), respectively. Additionally, the placebo cohort had 23% (3/13) of participants with a positive response for at least one time point post-vaccination.

Association of immunological endpoints

The correlation between the maximum post-vaccination titers of various humoral responses was examined across all cohorts (Table 2). Serum IgA had a strong correlation (Spearman coefficient, rs,>0.5, p < 0.05) with ALS IgA in all cohorts except those receiving 1.0 µg of dmLT, or a single dose of 2.0 µg, which were both nearly significant, p = 0.053, 0.052, respectively. Serum IgA was also strongly correlated with LT neutralizing antibodies (rs>0.5, p < 0.05) for all cohorts receiving dmLT. Serum IgG was strongly correlated to ALS IgG for those receiving 0.1 µg, 1.0 µg, and one or two doses of 2.0 µg of dmLT (rs>0.5, p < 0.05). Similarly, serum IgG was correlated with LT neutralizing antibodies (rs>0.7, p < 0.05) in all treatment groups except the lowest dosage (Cohort 1, 0.1 µg of dmLT) and in those receiving three doses of 2.0 µg dmLT (Cohort 4 + 5 C). ALS IgA was only correlated with serum LT neutralizing antibodies in participants who received 1.0 µg of dmLT (rs=0.67, p = 0.018) and those who received a single dose of 2.0 µg of dmLT (rs=0.71, p = 0.004). ALS IgG was correlated with LT neutralizing antibodies (rs>0.5, p < 0.05) in all treatment groups except the lowest dosage, 0.1 µg, (rs=0.25, p = 0.426) and those receiving three doses of 2.0 µg of dmLT (rs = −0.20, p = 0.418).

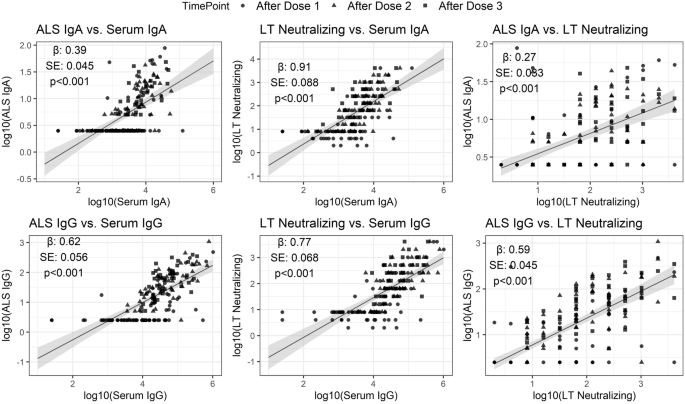

To account for timing of vaccinations, the maximum titers after each vaccination, as applicable and after final vaccination were correlated through generalized estimating equation (GEE) analysis across all dmLT recipients regardless of dosage amount or number of vaccinations (Fig. 6, Table 3). In the GEE model, participant ID was used as a clustering variable for each analyzed pair of immunological markers to account for the multiple time points. LT neutralizing antibodies were positively associated to serum IgA (effect estimate, β, =0.91 ± 0.09, p < 0.001) and IgG (β = 0.77 ± 0.07, p < 0.001), as well as to ALS IgA (β = 0.27 ± 0.03, p < 0.001) and IgG (β = 0.59 ± 0.05, p < 0.001). IgA in serum was positively associated with IgA in ALS (β = 0.39 ± 0.05, p < 0.001), a trend which also was observed between IgG antibodies (β = 0.62 ± 0.06, p < 0.001).

Data represent maximum titers after each dose, as applicable, and after final vaccination for all cohorts. Effect estimate (β), standard error (SE) and p value significance (p) reported for each comparison.

Discussion

This single-center, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, Phase 1 dose escalation study in healthy adults demonstrated the tolerability and immunogenicity of dmLT as a potential ETEC candidate vaccine, administered by the ID route. The study design involved an initial dose escalation (0.1 µg–2.0 µg) of dmLT given ID on three occasions, and the evaluation of the most immunogenic and well tolerated dosage level (2.0 µg) in either one, two, or three occasions.

All dosage levels and regimens were safe and well tolerated; solicited reactions were mostly local and mild, and no severe solicited symptoms were reported for any of the cohorts. The most common local symptoms were induration and erythema, whereas the most common systemic events were GI related. Local hyperpigmentation was also common in dmLT recipients and persisted up to several months but was absent in those receiving the placebo. Long lasting hyperpigmentation and erythema were also reported as common reactions in subjects who received LT delivered by transcutaneous patch10,12. Erythema followed by induration and hyperpigmentation were likewise reported in subjects who received 0.1 µg of mLT combined with ETEC CfaE ID16,24. Biopsy and histopathology from some of these subjects suggested residual chronic inflammation. Mild induration, hyperpigmentation and pruritis at the injection site were reported in volunteers that received 0.47 µg of dmLT with fIPV ID25. Because our study included multiple doses and dose escalations, we were able to show that occurrence of hyperpigmentation increased with dosage level but was not affected by subsequent immunizations. We interpret this local event as a toxin-triggered local inflammatory response that likely included innate immune cell tissue infiltration. In line with this hypothesis, we previously reported a rapid recruitment of large numbers of neutrophils, followed by macrophages, dendritic and Langerhans cells, in mice immunized ID with dmLT and Shigella proteins31.

The antibody responses to dmLT given ID in this study were very strong. At least two doses of 2.0 μg of dmLT were the most immunogenic, eliciting complete and long-lasting IgG and IgA seroconversion. Comparisons with other clinical studies that examined immune responses to LT or mutant LT molecules are challenging because of differences in assay methods and data reporting. Nonetheless, the frequency of IgG and IgA responses elicited by ID-delivered dmLT in our study appears to be similar to those reported for individuals immunized with 50 µg of LT in a patch12 or 0.1 µg of mLT given ID16.

Importantly, dmLT given ID in our study elicited long-lasting LT neutralizing antibodies. The cohorts that received three doses of 2.0 μg of dmLT were the highest responders and those with the highest retention of immunity six-months after final vaccination. These results demonstrate that ID dmLT delivery elicits not only binding (i.e., by ELISA) but also long lasting, functionally active antibodies capable of blocking the toxin attachment to host tissues and its cytopathic effect.

ALS are a proxy for the presence of antibody-secreting plasmablasts in circulation32,33,34. A majority of the individuals who received dmLT given ID developed ALS IgG and IgA responses (84.0% and 63.0%, respectively), which indicates activation of vaccine-specific B cells.

Notably, we report for the first time, that peak dmLT-specific serum IgA and IgG responses were strongly correlated with peak ALS IgG and IgA responses in most study groups receiving dmLT, and both serum and ALS IgG and IgA were in turn associated with LT neutralizing antibodies. It was noticed that some of the correlations lacked significance for the group that received the highest dose of dmLT (2.0 µg). One possibility is that antibody levels reached a plateau in this group resulting in a lack of linearity in the comparisons. The agreement among antibody responses supports the option of streamlining measurements in future studies, possibly focusing on serum binding outcomes and demonstration of toxin neutralization increases at peak and late follow up time points.

The induction of mucosal IgA was much lower than systemic responses; less than half of the participants who received three vaccinations of 2.0 μg dmLT exhibited a positive fecal IgA response. Crothers et al. report minimal fecal IgA responses against IPV antigens in individuals that received fIPV co-administered with dmLT, although dmLT responses per se were not reported25.

A number of vaccines against ETEC containing various antigens and dmLT as adjuvant have been tested in clinical trials in the past few years. Lee et al.26 found a clear dmLT adjuvanticity in the antibody responses induced by IM administered CS6 vaccine. A study of ETVAX delivered orally with and without dmLT adjuvant found that significantly more infants developed fecal secretory IgA responses when they received vaccine + dmLT in comparison with those that received vaccine alone28. The dmLT adjuvant given orally with ETVAX improved expression of B cell memory markers in vaccinated adults and T cell responses in Bangladeshi adults and infants35,36. In a follow-on field study, the dmLT adjuvanted ETVAX vaccine was shown to provide protection against ETEC diarrhea in Finnish travelers to Benin in West Africa37.

The ID route is practical and appealing for its dose-sparing properties. Other benefits include lower costs and potential improvement in compliance due to fewer doses required38. These features are advantageous in situations of vaccine shortage or of increased demand (i.e., during an outbreak). Its safety profile appears to be generally comparable to IM and subcutaneous (SC) routes, although minor local reactions (erythema, pruritus, and pigmentation) appear to be more frequent. New devices for easier to use, more accurate, reliable, and safe ID delivery are being explored39. The World Health Organization supports the use of ID vaccination for certain diseases (i.e., rabies and polio) due to its cost effectiveness and vaccine efficiency.

Limitations of this study include the different follow-up lengths for the collection of samples between cohorts 1-4 and cohorts 5A-C, which prevented the assessment of the durability of immunity in the low dosage groups. Because there is no established correlate of protection for ETEC, the protective efficacy of dmLT given ID remains to be determined. Nevertheless, the high levels of LT neutralizing antibodies observed suggest the induction of critical anti-microbial immunity.

The utility of dmLT given ID as a stand-alone vaccine or as a vaccine adjuvant to help prevent ETEC or other enteric infections remains to be determined. The encouraging safety and immunological results detailed in this report should serve to facilitate further testing of dmLT-ID as an ETEC vaccine antigen and support its use in combination vaccines as well as a vaccine adjuvant for vaccine developers considering parenterally delivered products. The full health benefit of acquiring dmLT-immunity for reduction of ETEC and overall diarrhea severity for travelers and infants and children in low- and middle-income countries may not yet be fully appreciated. Thus, more clinical investigation is needed to better understand the benefits of dmLT immunization and to optimize routes of delivery to realize the potential for dmLT as both an ETEC antigen and vaccine adjuvant40,41. The results presented here demonstrate its safety and robust immunogenicity when administered to healthy adults in multiple doses of up to 2.0 µg using the ID route. The vaccine and immunostimulatory properties of dmLT also make it an attractive component for inclusion in combination vaccines against enteric pathogens under development. The results from our study support further clinical evaluation of dmLT administered ID, particularly its ability to afford or enhance protective efficacy against ETEC and contribute to protection against other enteric pathogens.

Methods

Participants

This single-center, outpatient, randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, Phase 1 dose escalation study in healthy adults was designed to determine the safety and immunogenicity of attenuated recombinant dmLT as a potential ETEC candidate vaccine, administered by the ID route. The study began enrollment in July 2016 and concluded in May 2020.

Healthy males and non-pregnant females between 18 and 45 years of age, inclusive, who were in good health and met all eligibility criteria (history, physical exam, and clinical laboratory tests, including pregnancy test for women of childbearing potential) were recruited at a single site, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC). Subjects who tested positive for Hepatitis B and C and HIV were excluded. Additionally, subjects could not have received any prior vaccinations or challenges with E. coli or cholera, or antibiotics within two weeks of vaccination. Subjects with a positive urine drug screen for opiates were excluded. Subjects with either previous experimental E. coli, LT, or cholera vaccines or live E. coli or Vibrio cholera challenges were excluded. Similarly, subjects were excluded if they had a known infection of cholera or diarrheagenic E. coli, or had traveled to, or planned to travel to during the study-period, ETEC-endemic areas in the past three years (defined as Africa, Middle East, South Asia, and Central or South America). The complete eligibility criteria are published at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02531685.

The study protocol and informed consent were approved by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Division of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (DMID) and the institutional review board at CCHMC. Participants provided written informed consent prior to any study activities. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Randomization and blinding

The list of randomized treatment assignments for all cohorts was prepared by statisticians at The Emmes Company using SAS software (version 9.3) and included in the enrollment module of The Emmes Company’s Internet Data Entry System (IDES). Randomization was stratified by study cohort and used permuted block randomization. Cohorts 1-3 were randomized using one block of six (allocation ratio of 5:1 dmLT to placebo) and two blocks of five (allocation ratio 4:1 dmLT to placebo). The Cohort 4 sentinels were randomized in a block of 6 (allocation ratio 5:1 dmLT to placebo), and the remainder of Cohort 4 was randomized in two blocks of five (allocation ratio 4:1 dmLT to placebo). Cohort 5 subjects were randomized to a dose schedule and a treatment using an allocation ratio of 11:1:12:1:8:2 one dose dmLT: one dose placebo: two doses dmLT: two doses placebo: three doses dmLT: three doses placebo. The number of doses was known to all subjects and study staff.

Blinded site staff entered demographic and eligibility-related data into the IDES. Once eligibility was confirmed, the IDES assigned each enrolled subject a blinded treatment code from the list of randomized treatment assignments. A designated unblinded individual at the site was provided with a treatment key, which linked the blinded treatment code to the actual treatment assignment and was kept in a locked and secure place with limited access.

The unblinded Research Pharmacist performed all preparations of the study product. Preparation of the study product and administration to the subjects occurred in separate rooms to preserve the blinding of staff except for the Research Pharmacist and unblinded vaccine administrator. The study subjects, the study personnel who performed study assessments after the administration of the study product, data entry personnel at the site, and laboratory personnel performing immunologic assays were blinded to treatment assignment. The immunology laboratory also remained blinded subject ID and visit number. The DSMB was provided an unblinded study report, with the treatment group identified, to review in the closed session of the DSMB meeting.

Study design

The study was designed to include four increasing dosages (0.1, 0.3, 1.0, and 2.0 µg) of dmLT ID through three immunizations. A total of 13 vaccinees and 3 placebos were enrolled in each cohort to account for loss of follow-up of evaluable participants. After reviewing Cohorts 1-3 (0.1 μg–1.0 μg), the Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) recommended a sentinel group to be added to Cohort 4, increasing the number to 17 vaccinees. After completion of Cohorts 1-4, the optimal dosage for inducing immune responses with no safety concerns was determined to be 2.0 µg. The final cohort (Cohort 5, n = 35) was randomized to receive one (Cohort 5 A, n = 12, 11 vaccinees and 1 placebo), two (Cohort 5B, n = 13, 12 vaccinees and 1 placebo), or three vaccinations (Cohort 5 C, n = 10, 8 vaccinees and 2 placebo) of 2.0 µg dmLT or placebo.

Treatment was administered within 15 minutes of preparing the syringe, intradermally (into the inner surface between the layers of dermis) over the deltoid area of the preferred arm. Following vaccinations, subjects remained in the clinic for observation for a minimum of 30 minutes.

The details of number of subjects included and excluded per cohort are summarized in Fig. 1.

Sample size

The initial recruitment for Cohorts 1-4 planned for a sample size of ten evaluable vaccine subjects and one evaluable placebo subject. These numbers were chosen as an appropriate group size for a Phase 1 study to evaluate a new vaccine in humans. Placebo subjects were included to reduce observer bias and not for statistical comparisons. Evaluable subjects were defined as those who received all vaccinations and completed Day 50 of safety follow-up. With 40 expected evaluable vaccine subjects in Cohorts 1-4, the absence of a dose-limiting AE provided for an exact upper 95% confidence bound of 8.8%.

The highest tolerated dosage (2.0 µg) was then evaluated in a confirmatory cohort (Cohort 5) of 25 evaluable vaccine recipients and at least 2 evaluable placebo subjects. Through all five cohorts, with an overall expected total of 65 evaluable vaccine subjects, the absence of a dose-limiting AE provided for an exact upper 95% confidence bound of 5.5%.

Vaccine

ETEC dmLT (LTR192G/L211 Lot No. 1575), conforming to cGMP specifications, was produced at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR Pilot BioProduction Facility Forest Glen, MD) and used in Cohorts 1-4. For Cohort 5, another lot of dmLT, Lot 001-08-16, was produced to cGMP specifications by IDT Biologika Dessau. Both dmLT lots had the same analytical characteristics based on release and stability test specifications. Lyophilized dmLT vaccine was reconstituted to 1 mg/mL using sterile water for injection and kept on wet ice or refrigerated (up to 6 h) until diluted in 0.9% normal saline to the appropriate dosing level, delivered in 0.1 mL volume. The amount of dmLT was verified by PATH in each dosage level using a previously published SDS-PAGE densitometry method42.

Outcomes

The primary objective of the study was to assess the safety and tolerability of the ETEC dmLT vaccine when administered in three doses intradermally over a range of dosages in healthy adult subjects. The secondary objectives reported here were to assess long-term safety follow-up from immunization through six months post-last vaccination and to evaluate dmLT-specific immune response via LT neutralization and IgA- and IgG-response in serum, lymphocyte supernatant, and feces.

Serum and fecal antibodies

Initial measurements were collected prior to any vaccinations on day 1 for all immune response measurements. Layout of timing of assay measurements depicted in Table 4.

In all cohorts, serum antibody samples were collected as follows.

-

Cohort 1-4, 5 C (Three vaccinations): Day 1, 8, 22, 29, 43, 50, 64, 71, 99, 223 (5 C only)

-

Cohort 5 A (One Vaccination): Day 1, 8, 22, 29, 57, 181

-

Cohort 5B (Two Vaccinations): Day 1, 8, 22, 29, 43, 50, 78, 202

Serum dmLT-specific IgA and IgG were measured by ELISA as previously described14. LT-toxin neutralizing antibodies were measured using an assay adapted from Glenn et al.43 and described in detail elsewhere14. End-point titers are reported as the reciprocal of the highest serum dilution that resulted in ≥50% reduction in toxin activity.

In all cohorts, stool antibody samples were collected as follows.

-

Cohort 1-4, 5 C (Three vaccinations): Day 1, 8, 22, 29, 43, 50, 64, 71

-

Cohort 5 A (One Vaccination): Day 1, 8, 22, 29

-

Cohort 5B (Two Vaccinations): Day 1, 8, 22, 29, 43, 50

Total and dmLT-specific IgA were measured in stool supernatants as previously described44,45. The limit of detection (LOD) for the dmLT-specific IgA ELISA is 3.0 ng/mL. Values after baseline that were below the limit of detection were excluded from analysis. Values below LOD at baseline were denoted 3.0 ng/mL to assume the worse-case scenario and avoid post vaccination false responders.

Antibodies in lymphocyte supernatants (ALS)

ALS samples were collected prior to first vaccination, and seven days after each subsequent vaccination [Days: 1, 8, 29, and 50]. For ALS measurements, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (1×107 cells/mL in complete Roswell Park Memorial Institute Medium [RPMI]) were incubated for 72 hours at 37 oC and 5% CO2. The supernatants were collected and stored at -20 oC until tested by ELISA.

Safety analysis

Safety was assessed by solicited adverse events (AEs) using a memory aid through seven days after each dose, clinical laboratory AEs through seven days after each dose, and unsolicited AEs from the time of vaccination through six months after the last study vaccination. Unsolicited AEs were coded by the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA®) for the preferred term and system organ class. The safety analysis population included all subjects who received at least one dose of the study product (N = 100); participants were analyzed according to their randomized cohort even if they did not receive all planned vaccinations.

Immunogenicity analysis

The immunogenicity data are presented for the per protocol (PP) population, which includes all subjects who received at least one dose of study product and contributed both pre- and at least one post-study vaccination sample for which valid results were reported and excludes participants found to be ineligible at baseline (n = 1), data from visits subsequent to major protocol deviations, and data from visits that were out of window. Participants in Cohorts 4 and 5 C who did not receive all scheduled vaccinations were analyzed according to the number of vaccinations actually received. Two participants randomized to Cohort 4 and one participant randomized to Cohort 5 C only received two vaccinations and were analyzed with Cohort 5B. Four participants randomized to Cohort 4 only received one vaccination and were analyzed with Cohort 5 A.

All antibody responses were represented as percent responders, as well as both geometric mean fold-rise (GMFR) and geometric mean titer (GMT) with respective 95% confidence intervals. Serum antibody and serum LT-toxin neutralization antibody responders were defined as those with a ≥ 4-fold rise from baseline. ALS responders were defined as those with an increase of ≥ 2-fold over baseline. Fecal IgA antibodies were calculated by the ratio of dmLT-specific IgA to total IgA, and a positive response defined as a ≥ 4-fold increase of the ratio over the baseline ratio.

The relatedness of immune response biomarkers was first assessed by Spearman correlation for the maximum assay response beyond the baseline sample. Spearman correlations with p < 0.05 and correlation coefficient, rs, >0.5 were defined as strong correlations. There were no corrections for multiple comparisons as this was an exploratory analysis.

Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) analysis was performed on PP population of vaccinees, using the maximum titer during the period after final vaccination and between vaccinations (Dose 1 and Dose 2; Dose 2 and Dose 3), as applicable based on number of vaccinations received for each participant. Values were log10-transformed before modeling, and participant ID was included as a clustering variable to account for the multiple time points. Marginal means of each model with a 95% confidence interval was graphed for each biomarker pair.

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software (version 9.4) and RStudio (version 4.4.1). R packages used include ggplot2, ggpubr, DescTools, geepack, ggeffects, and EnvStats46,47,48,49,50,51,52.

Responses