SARS-CoV-2 infection primes cross-protective respiratory IgA in a MyD88- and MAVS-dependent manner

Introduction

The continuing pandemic potential of respiratory viruses remains a serious threat to public health, as evidenced by the global impact of the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic1. As of December 8, 2024, over 777 million people have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, and more than 7 million people have died from COVID-19 worldwide. Respiratory viruses spread by direct contact, fomite transmission, or airborne transmission and are transferred to mucosal surfaces of exposed individuals2,3. Thus, mucosal antiviral IgA play an important role in protecting against respiratory virus infection by blocking virus attachment to and release from host cells and by activating antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis, and the complement pathway4.

Mounting evidence indicates that antiviral respiratory IgA is more effective and cross-protective against homologous and heterologous influenza virus infections than circulating IgG antibodies induced by parenteral vaccines4,5,6, probably due to the increased avidity resulting from its multimeric nature7. Similarly, respiratory antiviral IgA induced by intranasal vaccination plays an important role in protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection by reducing the viral load, disease severity, and airborne transmission8,9. Gut microbiota and MyD88 signaling are essential for the induction of the virus-specific nasal and salivary IgA antibodies after respiratory influenza virus infection10,11,12. In contrast, the role of innate immune signals required for the induction of the virus-specific mucosal antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 infection remains unknown.

Mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 variants are useful for studying vaccine development and the viral pathogenesis. Here we establish mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 alpha, gamma, and omicron BA.1 variants. By using the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 variant, we show that the levels of antiviral IgA in the respiratory tract correlate with cross-protection against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection. In addition, we demonstrate that MyD88 and MAVS signaling play a role in the induction of the memory IgA response following intranasal booster with unadjuvanted Spike protein in mice recovered from the SARS-CoV-2 infection. These findings provide a useful basis for the development of effective mucosal vaccines against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Results

Intranasal vaccine is superior to parenteral vaccine in blocking heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection in Syrian hamsters

We first investigated cross-protective effects against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 variants in hamsters recovered from an ancestral SARS-CoV-2 infection. To this end, we infected hamsters intranasally with ancestral SARS-CoV-2. Five weeks after the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 infection, we challenged the previously infected hamsters with homologous or heterologous SARS-CoV-2 variants. Then, we collected the lung washes at 3 days p.i. and measured virus titers by standard plaque assay. (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Infection of hamsters with ancestral SARS-CoV-2 elicited not only homologous but also heterologous virus cross-reactive IgG antibodies in serum at 5 weeks post infection (p.i.) (Supplementary Fig. 1b–f). In addition, the pre-infected hamsters completely blocked not only the homologous virus but also the heterologous SARS-CoV-2 virus replication at 3 days p.i. (Supplementary Fig. 1b–f).

Next, we compared the cross-protective effects of intranasal and intramuscular vaccination against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant challenge. To this end, we immunized hamsters intranasally or intramuscularly with formalin-inactivated ancestral SARS-CoV-2 virion twice with a 3-week interval. Two weeks after the booster, we challenged the vaccinated hamsters with a heterologous SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Both intramuscular and intranasal vaccinations elicited comparable levels of serum IgG antibodies against homologous and heterologous virions or the Spike protein (Supplementary Fig. 2b–d). These vaccinated hamsters significantly inhibited the pulmonary virus titer (Supplementary Fig. 2e) and body weight loss (Supplementary Fig. 2f) following heterologous SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant infection. In addition, both vaccinated groups increased survival following lethal SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant infection (Supplementary Fig. 2g). Importantly, the intranasally vaccinated hamsters completely suppressed the heterologous virus replication in the lung tissue (Supplementary Fig. 2e). These data suggest that mucosal immunity induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection or intranasal vaccination is superior to parenteral vaccine in blocking the virus entry or replication.

Generation of mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 variants

So far, we are unable to measure the virus-specific IgA responses in immunized hamsters because of a lack of an available anti-hamster IgA antibody. To examine the role of innate immune signals required for induction of mucosal IgA antibodies following SARS-CoV-2 infection or intranasal vaccination, we wished to generate mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 variants. To generate mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2, we first passed SARS-CoV-2 alpha (hCoV-19/Japan/QK002/2020), gamma (hCoV-19/Japan/TY7-503/2021), or omicron BA.1 (hCoV-19/Japan/TY38-873/2021) variants five times in aged mice and additional 75 times in young mice (named alpha P80, gamma P80, and omicron BA.1 P80 viruses, respectively). Next-generation sequencing analysis revealed that the alpha P80, gamma P80, and omicron BA.1 P80 virus contained 11, 19, and 18 amino acid substitutions that were distributed within the ORF1ab, S, E, M, Orf6, Orf7a, and N genes, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c and Supplementary Data 1). Next, we compared pathogenesis of these mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 variants in C57BL/6 mice. The pulmonary virus titers were significantly elevated in the lung of the gamma P80 virus-infected mice compared with those of alpha or BA.1 P80 virus-infected mice (Supplementary Fig. 3d). As a result of severe pulmonary edema, the lung weight was significantly increased in the gamma P80 virus-infected mice compared with those of alpha or BA.1 P80 virus-infected mice (Supplementary Fig. 3e). While the C57BL/6 mice were resistant to the alpha or BA.1 P80 virus infection, the gamma P80 virus caused lethal infection (Supplementary Fig. 3f, g).

Unadjuvanted intranasal Spike vaccine can elicit antiviral respiratory IgA

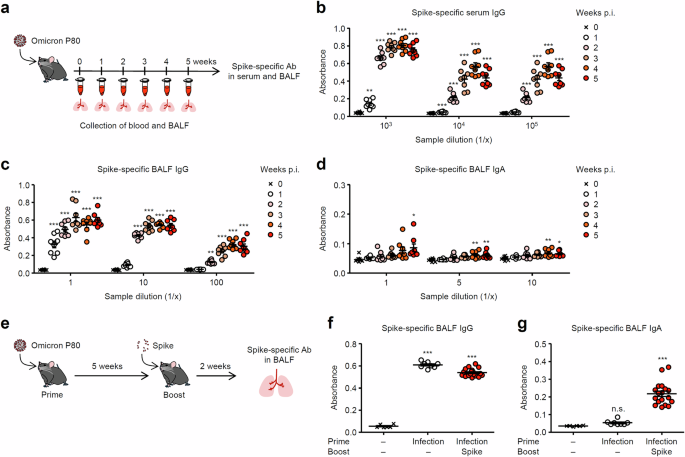

To examine the role of innate immune signals required for induction of antiviral mucosal IgA antibodies, we first measured the kinetic changes in the Spike-specific antibodies response following SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 1a). Infection of mice with 10 pfu of a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 omicron BA.1 P80 virus induced robust levels of the Spike-specific IgG antibodies in the serum and bronchoalveolar fluid (BALF) (Fig. 1b, c). In contrast, the omicron BA.1 P80 virus did not induce significant levels of the Spike-specific IgA antibodies in BALF (Fig. 1d). Similarly, infection of C57BL/6 mice with increasing doses (100 to 105 pfu) of the omicron BA.1 P80 virus did not induce significant levels of the Spike-specific IgA antibodies in BALF, compared to the group infected with 10 pfu of the virus (Supplementary Fig. 4). Since infection of Balb/c mice with 10 or 100 pfu of the omicron BA.1 P80 virus induced significant levels of the Spike-specific IgA antibodies in BALF (Supplementary Fig. 5), it is possible that the inadequate induction of the virus-specific IgA antibodies following the omicron BA.1 P80 virus infection is a characteristic immune response of C57BL/6 mice. A previous study demonstrated that intranasal booster with unadjuvanted the Spike protein elicits memory IgA antibodies response in the respiratory tract of mice previously primed with parenteral vaccines13. Thus, we next examined whether intranasal booster with unadjuvanted Spike protein induces memory IgA response in the respiratory tract of mice recovered from 10 pfu of the omicron BA.1 P80 virus infection. To test this possibility, we boosted previously infected mice with unadjuvanted Spike protein intranasally (Fig. 1e). Consistent with the previous report13, intranasal administration of previously infected mice with unadjuvanted Spike protein elicited robust levels of the Spike-specific IgA antibodies without affecting the levels of the Spike-specific IgG antibodies in BALF (Fig. 1f, g). An increase in the viral load during priming by 103 or 104 pfu significantly increased the levels of Spike-specific IgA antibodies in BALF following the intranasal Spike booster (Supplementary Fig. 6). These data indicate that primary infection of C57BL/6 mice with the omicron BA.1 P80 virus is insufficient to elicit respiratory antiviral IgA antibodies and that intranasal booster with unadjuvanted Spike protein can evoke robust levels of the virus-specific respiratory IgA antibodies in previously infected mice.

a Schematic representation of experimental setup. C57BL/6 mice were infected intranasally with 10 pfu of a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 BA.1 variant. b–d Serum and BALF were collected at indicated time points, and levels of the Spike-specific IgG (b, c) and IgA (d) antibodies were determined by ELISA. e, Schematic representation of experimental setup. C57BL/6 mice were infected intranasally with 10 pfu of a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 BA.1 variant. Five weeks later, mice were boosted intranasally with 5 μg of a recombinant Spike protein without adjuvant. f, g Two weeks after the booster, levels of the Spike-specific IgG (f) and IgA (g) antibodies in BALF were determined by ELISA. Each symbol indicates individual values (b–d, f, g). Data are mean ± s.e.m. Data are representative of two (b–d) or three independent experiments (f, g). Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (b–d, f, g). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n.s., not significant.

Intranasal booster protects mice from heterogeneous SARS-CoV-2 infection

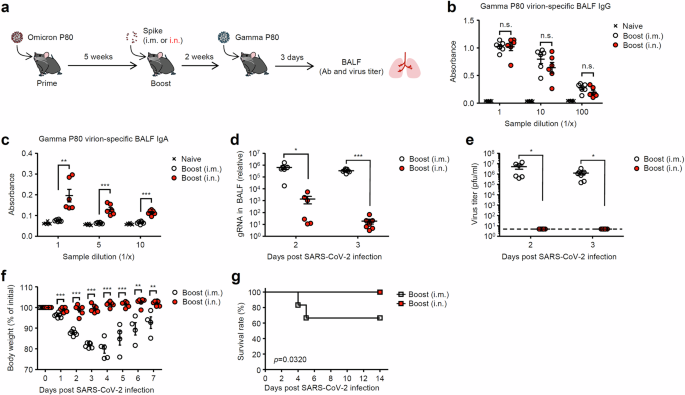

We next examined the relationship between the levels of antiviral IgA in respiratory tract and cross-protective effect against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection. To this end, we boosted mice recovered from BA.1 P80 virus infection with unadjuvanted Spike (BA.1) protein intranasally or intramuscularly. Two weeks after the boost vaccination, mice were challenged with a heterologous mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 gamma P80 virus (Fig. 2a). The levels of the gamma P80 virion cross-reactive IgG antibodies in BALF of immunized mice were comparable after the booster (Fig. 2b). In contrast, intranasal booster elicited robust levels of the gamma P80 virion cross-reactive IgA antibodies in BALF (Fig. 2c). Remarkably, the intranasally boosted group significantly reduced the levels of viral genome in the BALF and completely blocked the viral replication at 2 and 3 days p.i. (Fig. 2d, e). After the heterologous gamma P80 virus infection, intramuscularly boosted mice reduced their body weight by 20% and exacerbated the diseases, whereas intranasally boosted group were highly resistant to the heterologous virus infection (Fig. 2f, g). These data suggest that intranasal vaccine is superior to parenteral vaccine in protection against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection.

a Schematic representation of experimental setup. C57BL/6 mice were infected intranasally with 10 pfu of a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 BA.1 variant. Five weeks later, mice were boosted intranasally with 5 μg of a recombinant Spike protein without adjuvant. Two weeks after the booster, immunized mice were challenged with 1 × 106 pfu of a mouse-adapted heterologous SARS-CoV-2 gamma variant. b, c BALF was collected at 3 days postinfection, and levels of the gamma variant P80 virion-specific serum IgG (b) and IgA (c) antibodies in BALF were determined by ELISA. d, e BALF was collected at indicated time points, and levels of the viral genome RNA (d) or viral titers (e) were assessed by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (d) or standard plaque assay (e), respectively. The dashed line indicates the limit of virus detection (e). f, g Body weight (f) and mortality (g) were measured on indicated days after the challenge. Each symbol indicates individual values (b–f). Data are mean ± s.e.m. Data are representative of two independent experiments (b–g). Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (b, c), two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (d–f), or two-sided log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test (g). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n.s., not significant.

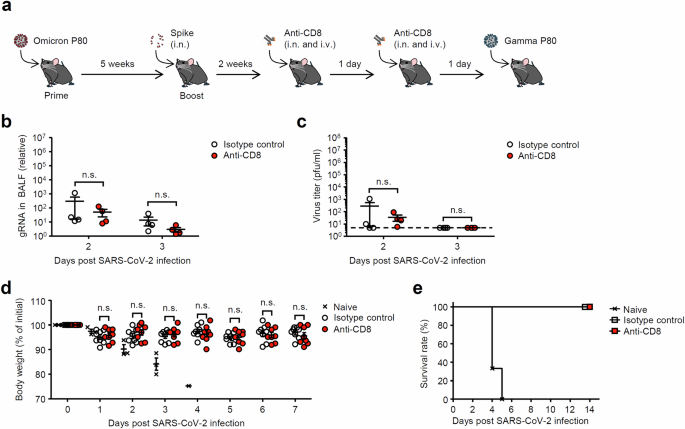

Recent studies indicate that CD8 T cells play a crucial role in protection against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection14,15. Therefore, we next examined the role of CD8 T cells in protection against heterologous gamma P80 virus infection after intranasal Spike booster. To this end, CD8 T cells were depleted by antibody against CD8 a few days before heterologous gamma P80 virus infection in intranasally boosted mice (Fig. 3a). Systemic and local administration of anti-CD8a antibody depleted CD8 T cells in lung and spleen (Supplementary Fig. 7). Depleting CD8 T cells in mice that had been immunized with an intranasal booster showed no significant difference in antiviral protection against heterologous gamma P80 virus infection compared to the control group (Fig. 3b–e). These data suggest that the antiviral protection conferred by the intranasal spike booster against heterologous gamma P80 virus infection is independent of CD8 T cell-mediated immunity.

a Schematic representation of experimental setup. C57BL/6 mice were infected intranasally with 10 pfu of a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 BA.1 variant. Five weeks later, mice were boosted intranasally with 5 μg of a recombinant Spike protein without adjuvant. Two weeks after the booster, mice were administered intranasally (17 μg) and intravenously (75 μg) with isotype rat IgG or anti-CD8 antibodies on days −2 and −1 before virus challenge. b, c BALF was collected at indicated time points, and levels of the viral genome RNA (b) or viral titers (c) were assessed by quantitative reverse transcription PCR (b) or standard plaque assay (c), respectively. The dashed line indicates the limit of virus detection (c). d, e Body weight (d) and mortality (e) were measured on indicated days after the challenge. Each symbol indicates individual values (b–d). Statistical significance was analyzed by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (b–d). n.s., not significant.

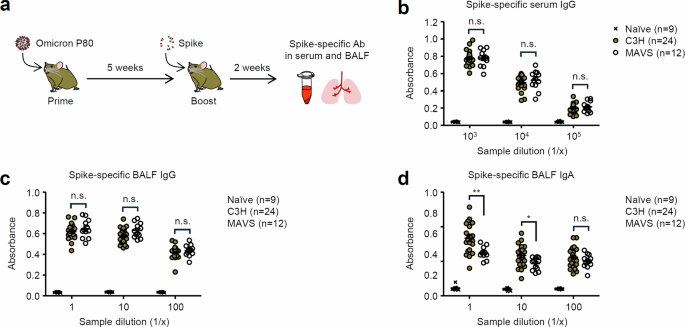

MyD88 and MAVS play a role in the induction of antiviral respiratory IgA by intranasal unadjuvanted Spike booster in previously infected mice

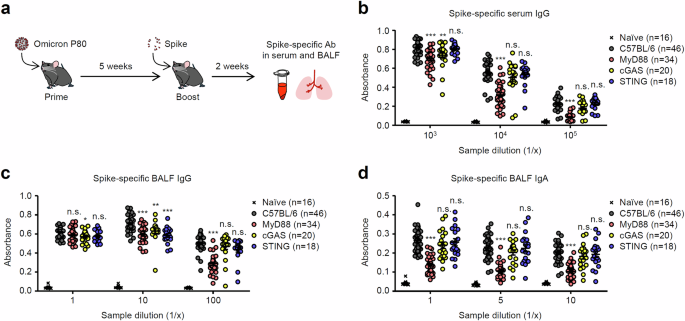

Previous studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 activates innate immune pathways, including MyD88, MAVS, and the cytosolic DNA-sensing cGAS-STING pathway16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. Furthermore, recent studies have demonstrated that intranasal administration of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike trimer adjuvanted with the STING agonist induces the Spike-specific IgA antibody and protects K18-hACE2 transgenic mice against challenges with SARS-CoV-2 variants26,27. However, the role of innate immune signaling required for the induction of Spike-specific IgA during SARS-CoV-2 infection remains completely unknown. Therefore, we wished to determine the role of innate immune signals required for induction of antiviral mucosal IgA antibodies in previously infected mice after intranasal unadjuvanted Spike booster. To this end, we infected wild-type (WT) C57BL/6, MyD88, cGAS, and STING knock out (KO) mice intranasally with the omicron BA.1 P80 virus. Five weeks after infection, we boosted these mice intranasally with unadjuvanted Spike protein (Fig. 4a). Notably, the Spike-specific IgG and IgA antibodies in the serum and BALF were severely impaired in mice deficient for MyD88, but not cGAS or STING (Fig. 4b–d). To test whether the defect in inducing Spike-specific IgA antibodies responses in MyD88 KO mice correlates with their failure to migrate respiratory tract dendritic cells (DCs) into the mediastinal lymph node (mLN) upon SARS-CoV-2 infection, we intranasally inoculated mice with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) and enumerated lung-migrant DCs in the mLN 18 h postinfection. Migration of lung DCs to the mLN was severely impaired in MyD88 KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). In addition, expression levels of MHC class II and CD86 were lower in DCs from MyD88 KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 8c). These data suggest that MyD88 signals are required for lung DCs to migrate to the mLN after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Finally, we examined the role of MAVS, an adapter molecule for cytosolic RNA sensors, in the induction of antiviral mucosal IgA antibodies in previously infected mice after intranasal unadjuvanted Spike booster. To this end, we infected WT (C3H) and MAVS KO mice intranasally with the omicron BA.1 P80 virus and boosted them intranasally with unadjuvanted Spike protein (Fig. 5a). The Spike-specific BALF IgA but not serum or BALF IgG antibodies were significantly reduced in MAVS KO mice (Fig. 5b–d). Together, these data suggest that MyD88 and MAVS signals play a role in the induction of antiviral respiratory IgA by intranasal unadjuvanted Spike booster in previously infected mice.

a Schematic representation of experimental setup. C57BL/6 WT, MyD88, cGAS, or STING KO mice were infected intranasally with 10 pfu of a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 BA.1 variant. Five weeks later, mice were boosted intranasally with 5 μg of a recombinant Spike protein without adjuvant. b–d Two weeks after the booster, serum (b) and BALF (c, d) were collected, and levels of the Spike-specific IgG (b, c) and IgA (d) antibodies were determined by ELISA. Each symbol indicates individual values (b–d). Data are mean ± s.e.m. Data are pooled from three independent experiments (b–d). Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (b–d). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, n.s., not significant.

a Schematic representation of experimental setup. C3H WT or MAVS KO mice were infected intranasally with 10 pfu of a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 BA.1 variant. Five weeks later, mice were boosted intranasally with 5 μg of a recombinant Spike protein without adjuvant. b–d Two weeks after the booster, serum (b) and BALF (c, d) were collected, and levels of the Spike-specific IgG (b, c) and IgA (d) antibodies were determined by ELISA. Each symbol indicates individual values (b–d). Data are mean ± s.e.m. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (b–d). Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (b–d). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, n.s., not significant.

Discussion

Respiratory tract epithelial cells are the primary target for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Therefore, the mucosal immune systems, especially secretory IgA antibodies, play the most important role in protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our results showed that hamsters recovered from ancestral SARS-CoV-2 infection were cross-protective against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 alpha, gamma, delta, and omicron variants infection. In this study, it was difficult to determine whether the virus-specific respiratory IgA contributes to cross-protection against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters due to a lack of an available anti-hamster IgA antibody. Given that none of the hamsters immunized intranasally, but not intramuscularly, detected infectious virus in BALF following heterologous SARS-CoV-2 alpha variant infection, we speculate that antiviral respiratory IgA antibodies induced by intranasal vaccination contribute to cross-protection against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection in hamsters.

To examine the role of innate immune signals required for induction of mucosal IgA to SARS-CoV-2 infection in mice, we established three mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 variants by serial passaging 80 times in mice. During 80 serial passages in mice, the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 alpha, gamma, and BA.1 variants acquired 11, 19, and 18 amino acid substitutions throughout the viral genome, respectively. Although the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 alpha and BA.1 variants did not cause lethal infection, the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 gamma variant caused severe pulmonary edema and lethal infection in 6-week-old young C57BL/6 mice. In addition, the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 gamma variant significantly enhanced viral replication in the lung tissue compared to the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 alpha and BA.1 variants. The mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 gamma variant is characterized by a few amino acid substitutions in nsp3, nsp6, M, and receptor binding domain (RBD) of the Spike protein. Since multiple SARS-CoV-2 proteins antagonize type I IFN production and signaling28,29,30, these amino acid substitutions in nsp3, nsp6, and M proteins of the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 gamma variant could contribute to inhibit host interferon responses and efficient viral replication in vivo.

BALB/c mice develop more robust respiratory IgA responses to intranasally administered antigens than that of their C57BL/6 counterparts, probably due to the difference in total IgA amounts in these mouse strains31. Thus, we usually use the BALB/c mice as a model animal for developing intranasal vaccine against influenza virus or SARS-CoV-232,33,34,35,36. In this study, we used C57BL/6 mice as WT controls for MyD88, cGAS, STING, and IFNAR1 KO mice to examine the role of innate immune signals required for induction of mucosal IgA antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 infection. In C57BL/6 mice, infection with a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant failed to induce significant levels of the Spike-specific IgA antibodies in BALF, while the levels of the Spike-specific IgG antibodies in serum and BALF were significantly increased following the virus infection. However, intranasal booster with unadjuvanted Spike protein evoked robust levels of the virus-specific respiratory IgA antibodies in previously infected mice. These data suggest that primary infection with a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant led to the establishment of lung-resident IgA-secreting B cells and secondary intranasal, but not intramuscular, booster with unadjuvanted Spike protein stimulates robust levels of the virus-specific respiratory IgA antibodies in the BALF. Importantly, levels of the respiratory antiviral IgA antibodies correlated with superior protection against heterologous a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 gamma variant challenge than the respiratory antiviral IgG antibodies. In addition, our results demonstrated that CD8 T cell depletion did not significantly alter the antiviral protection provided by the intranasal Spike booster. This suggests that the protection conferred by intranasal Spike boosters is independent of CD8 T cell-mediated immunity. These findings highlight the predominant role of mucosal IgA antibodies in cross-protection and further support our hypothesis that respiratory antiviral IgA antibodies, rather than cellular immune responses, are the primary mediators of protection against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thus, understanding the mechanisms by which SARS-CoV-2 infection led to the establishment of lung-resident IgA-secreting B cells are essential for development of effective mucosal vaccines against future SARS-CoV-2 variants that rapidly evolve the mutations in the Spike protein to evade humoral immunity.

Although the mechanism by which influenza virus infection induce the virus-specific adaptive immune responses has been extensively studied10,12,37,38,39, the role of innate immune signals required for induction of mucosal antibodies responses following SARS-CoV-2 infection remains less clear. In this study, we demonstrate that MyD88 and MAVS signals play a role in the induction of antiviral respiratory IgA after intranasal booster of mice recovered from primary infection with unadjuvanted Spike protein. To further investigate the role of MyD88 in the induction of mucosal IgA responses, we examined the migration of respiratory tract DCs to the mLN in MyD88 KO mice. Our results showed that the migration of lung DCs to the mLN was severely impaired in MyD88 KO mice following SARS-CoV-2 infection, as indicated by reduced CFSE-labeled lung-migrant DCs in the mLN. Moreover, DCs from MyD88 KO mice exhibited lower expression levels of MHC class II and CD86 compared to WT controls. These findings suggest that MyD88 signals are required not only for the migration of lung DCs to the mLN but also for their activation, which could subsequently impact the induction of IgA responses. Thus, defective migration and activation of lung DCs may partially explain the impaired antiviral IgA responses observed in MyD88 KO mice. A previous study showed that toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) senses the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines through MyD8840. Thus, the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein and cytosolic viral RNA may activate the innate immune signals such as MyD88 and MAVS to evoke establishment of the lung-resident IgA secreting B cells. In addition to the recognition of the viral envelope protein by TLR2, cytosolic chromatin fragment released from the nucleus activates the cGAS-STING pathway following SARS-CoV-2 infection19. Deficiency in cGAS or STING had a moderate effect on induction of systemic and local antiviral IgG, but not respiratory IgA, antibodies responses following intranasal booster with unadjuvanted Spike protein in mice recovered from the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Although the detailed mechanism needs to be further elucidated in future studies, our data collectively indicate that MyD88 and MAVS signals play a role in the induction of antiviral respiratory IgA after intranasal Spike booster of mice recovered from primary infection. In addition, it remains possible that innate immune molecules tested, including MyD88, cGAS, STING, and MAVS, induce redundant signaling pathway that compensate for each other to evoke systemic and local antiviral IgG antibodies.

In summary, our data demonstrate that respiratory tract antiviral IgA antibodies are superior to circulating IgG antibodies in preventing heterologous SARS-CoV-2 infection. Intranasal administration of previously infected mice with unadjuvanted Spike protein elicits robust levels of the Spike-specific IgA antibodies. Induction of antiviral respiratory IgA antibodies following SARS-CoV-2 infection requires MyD88 and MAVS signaling. The knowledge gained from our current study may be useful in the development of cross-protective mucosal vaccines against heterologous SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

All experiments with SARS-CoV-2 were performed in enhanced biosafety level 3 (BSL3) containment laboratories at the University of Tokyo, in accordance with the institutional biosafety operating procedures. All animal experiments including generation of mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 variants were performed in accordance with University of Tokyo’s Regulations for Animal Care and Use, which were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of the Institute of Medical Science, the University of Tokyo (PA22-32).

Animals

Six-week-old female C57BL/6JJmsSlc, C3H/HeYokSlc mice, and 4-week-old female Syrian hamsters obtained from Japan SLC, Inc (Shizuoka, Japan). were used as WT controls. For generation of mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 variants, we used aged (46- to 48-week-old) female C57BL/6JJcl mice obtained from CLEA Japan, Inc. MyD88- and MAVS-deficient mice were purchased from Oriental Bioservice (Kyoto, Japan) and Jackson Laboratory (strain #008634), respectively.

Cell culture

VeroE6 cells stably expressing transmembrane protease serine 2 (VeroE6/TMPRSS2; JCRB Cell Bank 1819) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (low-glucose) (Nacalai Tesque, 08456-65) supplemented with 10% v/v fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% v/v penicillin (100 units/ml)/streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and G418 (1 mg ml−1; Nacalai Tesque, 16512-94).

Viruses

An ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain bearing aspartic acid at position 614 of Spike (S) protein (S-614D)41, the alpha variant hCoV-19/Japan/QK002/2020 (lineage B.1.1.7, GISAID ID: EPI_ISL_768526)42, the gamma variant hCoV-19/Japan/TY7-503/2021 (lineage P.1, GISAID ID: EPI_ISL_877769)43, the Delta variant hCoV-19/Japan/TY11-927-P1/2021 (lineage B.1.617.2, GISAID ID: EPI_ISL_2158617)44, and the omicron BA.1 variant hCoV-19/Japan/TY38-873/2021 (lineage BA.1.18, GISAID ID: EPI_ISL_7418017)45 were grown in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells for 2 or 3 days at 37 °C. Viral titers were quantified by a standard plaque assay using VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells and viral stock was stored at −80 °C.

For generation of mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 variants, 46- to 48-week-old C57BL/6 mice were intranasally infected with the alpha, gamma, or BA.1 variant. The lung washes were collected at 3 days p.i. Then VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells were inoculated with the lung washes to propagate the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 (refer to as P1). After 7 serial passages in aged mice, 6-weeks-old young C57BL/6 mice were intranasally infected with the P7 virus. The lung washes were collected at 3 days p.i. and VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells were inoculated with the lung washes to propagate the P8 virus. After 3 serial passages in young mice, we serially passaged the lung washes (P10 virus) of the virus-infected young mice every 3 days without virus propagation in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells. The mouse-adapted alpha, gamma, and BA.1 P80 viral stocks used in the experiments were grown in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells for 2 or 3 days at 37 °C. Viral titers were quantified by a standard plaque assay using VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells and viral stock was stored at −80 °C.

Whole-genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2

Whole-genome sequencing of the mouse-adapted SARS-CoV-2 variants were determined as described previously46. In brief, the sequence libraries were prepared using the SureSelect XT HS kit (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) and a custom panel designed against the SARS-CoV-2 reference genome (NC_045512.2) with a 6× tiling density using a 20 bp sliding window47. Paired-end sequencing of 2 × 151 bp reads was performed using the MiSeq sequencer (MGI, Shenzhen, China). After trimming the adapter sequences using Cutadapt version 3.2, the trimmed sequence reads were aligned to the reference genome of SARS-CoV-2 (GenBank accession number: NC_045512.2) using BWA version 0.7.17. After marking duplicate reads in the BAM files using SAMtools version 1.11 and Picard in GATK 4.2.0.0, variant calling was executed using Mutect2 in GATK 4.2.0.0. The consensus sequences were obtained using BCFtools version 1.9.

Vaccination and virus infection in vivo

An ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain grown in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells were treated with 0.1% formalin under constant shaking at 4 °C for a week. Virus inactivation was confirmed by the absence of cytopathic effects after inoculation of the inactivated virus into VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells for 3 days. Western blot analysis with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein (Abcam, ab272504; 1:1000) demonstrated that the formalin-inactivated virus contains 10 μg/ml Spike protein. For vaccination, Syrian hamsters were randomly divided into three groups: a control group (naive), an intramuscular vaccination group, and an intranasal vaccination group. In intramuscular vaccination group, 200 μl of formalin-inactivated virus was injected into each leg (2 μg of Spike protein/leg) without adjuvant. In intranasal vaccination group, 400 μl of formalin-inactivated virus was administered intranasally (4 μg of Spike protein/hamster) without adjuvant.

For intranasal infection, hamsters were infected intranasally with 3 × 106 pfu (in 150 μL) of SARS-CoV-2 under isoflurane anesthesia. Mice were infected intranasally with 10 or 1 × 106 pfu (in 50 μL) of the mouse-adapted variants, under isoflurane anesthesia. Mice recovered from the BA.1 P80 virus infection were boosted intranasally or intramuscularly with 5 μg of a recombinant Spike protein (Sino Biological Inc. 40589-V08B1). Baseline body weights were measured before infection. Mice and hamsters were deemed to have reached endpoint at 70% of starting weight. Aminals were euthanized under anesthesia with an overdose of isoflurane if severe disease symptoms or weight loss were observed.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from lung washes using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, 15596018) and reverse transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, 18080085) with a SARS-CoV-2 N reverse primer (5’-tctggttactgccagttgaatctg-3’). TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (TaKaRa, RR820A) and a LightCycler 1.5 instrument (Roche Diagnostics) were used for quantitative PCR with the following primers: SARS-CoV-2 N forward, 5’-gaccccaaaatcagcgaaat-3’, and reverse, 5’-tctggttactgccagttgaatctg-3’.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Serum and BALF were collected from the immunized mice or hamsters for measurement of the virion- or Spike-specific IgA and IgG antibodies. BALF was collected by washing the trachea and lungs of mice or hamsters twice by injecting a total of 2 ml low-glucose DMEM (Nacalai Tesque, 08456-65) containing 5% FBS. The levels of the virion- or Spike-specific IgA and IgG antibodies were determined by ELISA as described previously42. In brief, a 96-well plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 442404) was coated with 0.1% formalin-inactivated SARS-CoV-2 virion or a recombinant Spike protein (Sino Biological Inc. 40589-V08B1) with carbonate buffer. After overnight incubation at 4 °C, the coating antigen was removed and 200 μL per well of 2% FBS in PBS was added to the plates at room temperature for 1 h as a blocking solution. Serum and BALF were diluted with 2% FBS in PBS. The blocking solution was removed and 100 μL of diluted serum or BALF samples were then plated in the wells and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. After wells were washed in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20, the reactions were detected by goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, 115-035-003), goat anti-mouse IgA (Invitrogen, 626720), or goat anti-Syrian hamster IgG (Abcam, ab6892) antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP). Absorbance at 450 nm was measured by using Microplate Manager version 6 (Bio-Rad).

Measurement of virus titers

For measurement of SARS-CoV-2 titer, BALF was collected by washing the trachea and lungs of mice or hamsters twice by injecting a total of 2 ml low-glucose DMEM (Nacalai Tesque, 08456-65) containing 5% FBS. The virus titer was measured as follows: aliquots of 200 μl of serial 10-fold dilutions of the BALF by low-glucose DMEM containing 5% FBS were inoculated into VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells in 6-well plates. After 1 h of incubation, cells were washed with PBS thoroughly and overlaid with 2 ml of agar medium. The number of plaques in each well was counted 2 days after inoculation.

Flow cytometry

The single-cell suspension of lung, spleen, or mediastinal lymph node samples were prepared as previously described10,48. Briefly, lung, spleen, or mediastinal lymph node was minced using razor blades, and incubated in HBSS containing 2.5 mM Hepes and 1.3 mM EDTA at 37 °C for 30 min. The cells were suspended in PRMI containing 5% FBS, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM Hepes, and 0.5 mg/ml collagenase D (Roche, 11088882001) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Spleen and mediastinal lymph were minced using razor blades, and incubated in DMEM containing 1% FBS, 30 μg/ml DNase I (Roche, 10104159001), and 2 mg/ml collagenase D (Roche, 11088882001) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, The cells were suspended in HBSS containing 5% FBS and 5 mM EDTA at 37 °C for 5 min. The resulting cells were filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer (BD). A single-cell suspension was prepared after red blood cell lysis. For detection of CD4 T, CD8 T, B, or DCs, cells were incubated with PE-labeled anti-CD4 (Invitrogen, 12-0041-83; 1:200), APC-labeled anti-CD8 (Invitrogen, 17-0081-83; 1:200), APC-labeled anti-B220 (Invitrogen, 17-0452-82; 1:200), or eFluor 450-labeled anti-CD19 (Invitrogen, 48-0193-82; 1:200). To analyze surface expression of MHC-II and CD86 on DCs, cells were incubated with PE-labeled anti-MHC-II (Invitrogen, 12-5322-81; 1:200) or PE-labeled anti-CD86 (BioLegend, 105015; 1:200). Flow cytometric analysis was performed with CytoFLEX LX flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter). The final analysis and graphical output were performed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.).

In vivo depletion of CD8 T cells

To deplete CD8 T cells, mice were administered intranasally (17.5 μg in 70 μl) and intravenously (75 μg in 300 μl) with anti-CD8a (Invitrogen, 14-0081-85, clone 53-6.7) or corresponding isotype control antibody rat IgG2a (Invitrogen, 14-4321-85) on days −2 and −1 before analysis or infection. Twenty-hour hours later, spleen and lung were isolated and the frequency of CD8 T cells were determined by flow cytometry.

In vivo staining of respiratory DCs with CFSE

CFSE (Invitrogen, C34554) was dissolved at 1 mM in DMSO and subsequently diluted to 100 μM in PBS. CFSE (70 μl) was administered intranasally to each mouse after anesthesia as previously described12.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was tested using non-parametric one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s multiple comparison test, non-parametric Mann–Whitney t test, or Student’s two-tailed, unpaired t test where indicated in the figure legend, using PRISM software (version 5; GraphPad software). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Responses