Scaling deep at the margins: coproduction of nature-based solutions as decolonial research praxis in Cape Town

Introduction

Achieving sustainability and resilience through Nature-based Solutions (NbS) is leading to urban experimentation with new forms of infrastructure planning and governance, as cities seek to address climate change impacts and transition to sustainable futures1,2,3. Current urban resilience-building agendas have necessitated a re-design of water infrastructures from centralised, conventional legacy infrastructures to decentralised, hybridised infrastructure that may be more suited to the uncertainties of a warming climate4,5. In the urban water management sector, such hybrid infrastructures combine conventional infrastructure with low-tech and/or nature-based alternatives, thus better leveraging synergies with ecosystem service provision, socio-economic equity as well as sustainability concerns4,6.

The implementation of blue-green infrastructure (BGI) as part of a water-sensitive design (WSD) framework is seen as a complementary NbS to the deficits of conventional urban water services provision in addressing these challenges7,8. WSD takes a total water cycle view through the integration of built water infrastructure with BGI in a decentralised manner, with the aim of transitioning to a water-sensitive city—one that is resilient, liveable, productive and sustainable9,10. NbS such as WSD are founded upon transdisciplinarity, wherein coproduction is key to harnessing urban nature towards sustainability through broad participation, equitable distribution of benefits and the blending of traditional, local and scientific knowledges11,12.

However, ideas such as NbS and WSD, whose current iteration has been developed in the Global North, are not without their problems when implemented in the Global South13,14. First, hybrid infrastructure landscapes are already an ongoing reality in the Global South, where infrastructure deficits have led to citizens relying on decentralised, alternative infrastructures that exist parallel or emergentlyconnected to conventional infrastructures15,16,17,18. Second, when considering NbS implementation in post-colonial cities, any efforts that neglect place-based ecological injustices rooted in socio-material legacies of apartheid/colonial histories, the formal-informal continuum and pre-existing inequalities, are likely to miss the resilience-building mark and aggravate governance challenges19,20. Indeed with the conceptualisation of climate change as a form and product of colonisation, it is imperative to understand and ground any resilience-building and transformation efforts in the Global South on decolonial frameworks21,22.

The impact of sustainability experiments such as NbS initiatives is increasingly the focus of solutions-oriented transitions research, as evidenced in mounting real-world experimentation with transformative sustainability aspects e.g. Living Labs23,24,25. Within studies of NbS and other green transition approaches, how the impacts of urban experiments can be amplified, i.e. scaled up, scaled out or scaled deeper, remains a key under-addressed question26,27,28,29,30. The notion of ‘scaling deep’, remains the least understood of the sustainability impact amplification pathways (27 p.18, 31). ‘Scaling deep’ is an amplification pathway in which experimental initiatives such as NbS become stabilised and more deeply embedded in their contexts through social learning27,31. In scaling deep, change is rooted in the stories and experiences of stakeholders which lead to shifts in cultures, values and relations for and between different stakeholders; ideally changing how the socio-material contexts attached to the experiment are constituted27,32,33.

This paper is based on a collaborative project by the Universities of Cape Town and Copenhagen that aimed to ‘… generate knowledge on the physical and institutional integration of decentralised nature-based solutions into the urban water cycle.’ The project combined physical experimentation with WSD as a NbS with reflexive social learning processes and an exploration of governance aspects required to facilitate sustainability transitions towards water-sensitive futures at different scales in Cape Town. The physical experimentation focused on repurposing a stormwater detention pond in Mitchell’s Plain, Cape Town for the treatment and harvesting of surface runoff through Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR). MAR is a process where groundwater is replenished by purposefully infiltrating or pumping water into an aquifer. This provided a platform for engaging with local residents, exploring added functions for the repurposed pond area, e.g. amenity and livelihood support.

In post-apartheid contexts like South Africa, public green space represents an opportunity to address the spatial implications of centuries of unjust colonial urban development by taking a decolonial stance that actively seeks to subvert the colonial project by scaling deep to remember and recognise the impacts of colonial violence on peoples and spaces; to re-imagine possible futures of just urban spaces as well as to seek the just transformation and renewal of post-apartheid cities34. Thus, in this paper, relying on a decolonial lens, we aim to document and reflect on the scaling-deep transdisciplinary coproduction processes characterising the experimental implementation of WSD as a NbS at community scale in Cape Town. Engaging in place-based, solutions-oriented research, we sought to coproduce NbS knowledge on the possibilities for the multifunctional repurposing of a mono-functional stormwater retention pond, whilst also co-implementing a liveable green space with enhanced ecosystem service provision and biodiversity.

There is a need for such decolonially informed studies that ‘scale-deep’ to better understand the socio-ecological impulses driving landscape change in the Global South. Such an understanding can help stakeholders envision the nature-based possibilities that the 800-plus stormwater ponds in Cape Town may hold for reaching water-sensitive futures. Studies of scaling deep through the cocreation of local NbS in marginalised communities provide a view into the leverage points for employing the urban landscape to foster socio-ecological transformation in deeply divided societies. Lastly, the Covid-19 pandemic has aggravated the socio-environmental justice deficit in post-colonial cities35. This points to the need for decolonially informed urban studies22,36 that repoliticise the governance of urban socio-natures through experimentation as the basis for transitions to just futures37,38.

In the following sections we first present an elaboration of a decolonial-informed framework, mapping the dimensions that are key for understanding the potential for NbS coproduction through scaling deep in post-apartheid cities. We then reflect on the transdisciplinary coproduction process we undertook in Mitchell’s Plain case site, mapping the different modes and phases of coproduction from the perspective of different actors. We conclude with a discussion of some key dimensions for realising NbS potential in post-colonial cities, highlighting the importance of first scaling deep at the margins for just socio-ecological transitions.

Results

Understanding transdisciplinary coproduction of NbS as decolonial scaling deep

Transdisciplinarity is an important approach to researching and acting on the wicked problem of transforming societies towards sustainable, resilient futures39,40,41. Transdisciplinary coproduction focuses on ‘science with society’42,43 to increase the participation of actors from outside academia in knowledge production as well as in the co-implementation of public services thus contributing to sustainability transformations through transformative space-making44,45,46.

By involving different actors and weaving together their diverse strands of knowledge, transdisciplinary (socio-ecological) coproduction offers access to indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) that results in innovative knowledge and tangible sustainability action which would be difficult to achieve without collaboration, especially for NbS11,47,48. TD coproduction in the Global South should ideally provide transformative spaces wherein indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) play a central role49,50, thus allowing the academy to begin to address its complicity in the violence and dehumanising impacts of the colonial project19,51,52.

By connecting diverse stakeholders, TD coproduction offers a framework for guiding the alignment of knowledge, experimentation and action for global sustainability and transformation43,53. With its emphasis on integrating different ways of knowing, relating and doing; TD coproduction allows for a more decolonial, relational approach to achieving just, transformative pathways to sustainability. The different roles played by actors are tied to understanding all actors as moving embodiments of value sets, knowledge and agency; all of which is influential in the realisation of sustainability solutions54,55,56. Based on such an understanding of actors, scaling deep then offers a view into unexplored, hard-to-grasp leverage points such as agency, values and knowledge for fostering transformative change27,33. By extension, NbS that scale-deep by centering relations, mindsets and values, can tap into the intangible connections between peoples and nature, ideally opening up the space for re-working power assymetries between actors, as well as the emergence of organic stewardship and care for Nature11.

Cities like Cape Town are complex sites of colonial scars, intergenerational violence and dispossession57 in which past and current regimes of urban governance and research are implicated58. Climate change adaptation and decolonial transformation are intimately linked considerations when exploring resilience-building for sustainable futures via nature-based pathways for cities in the Global South21,59. Thus, seeing through a decolonial lens can help unpack some of the leverage points that scaling deep opens up in contexts of ‘deep unresolved difference’60, such as post-apartheid cities.

In the pursuit of just and transformative futures through NbS in post-colonial cities, a decolonial accounting for multiple extant knowledges and voices whilst creating safe spaces for the exploration of the socio-ecological tensions is necessary45. This can be achieved through the reflexive surfacing of the inner worlds of researchers and marginalised stakeholders61. This is where ‘scaling deep’ comes in: as a relationally-based amplification pathway, scaling deep within NbS experiments implies reflexively seeking/constructing generative socio-ecological spaces for the surfacing of tensions/conflict and working towards making that friction fruitful31.

The privileging of such relational perspectives in the design and evaluation of NbS is fundamental to the transformation of inherent settler-colonial spatial and racialized dynamics in post-colonial cities58. This is because while the framing of NbS is normatively virtuous, in reality, NbS are not innocent forms of climate action as can be seen through green rent-seeking and marginalising impulses found in some NbS implementation62,63. Thus, the integration of NbS as part of climate action in Southern cities also needs to rest on a reflexive deconstruction of the neoliberal logics sometimes inherent in climate action64,65. Without such reflection, the implementation of NbS may reproduce coloniality and inequality by privileging technological fixes for climate change that are rooted in unequal capitalist urbanism66,67.

Within decolonial scaling deep, this deconstruction involves reflexivity about the ‘multiple roles, positionalities and intersectionalities’ of researchers58,68, whilst acknowledging the complicity of the knowledge production regime in the colonial project that has produced the legacies of inequality, socio-ecological degradation and climate emergency43,52. It also requires researchers to make their ‘gaze and pose’ explicit i.e., their normative and experimental departure points for seeking just sustainabilities that account for values, power and politics in coproduction processes69. Lastly, relationality entails giving agency to the ‘marginalised other’ by engaging intimately with the embodied, lived, ecological and historical ways of being70,71.

Finding the margins: Making space for resistance and desire in scaling deep

What, then, are the key characteristics of decolonial scaling deep in societies of deep difference when seeking the TD coproduction of just socio-ecological futures? Studies highlight that sustainability and resilience transformations in the Global South are bound to be contested and subject to dilemmas58,70. As agents of the ‘colonial matrices of power’, researchers in post-colonial cities seeking transformative pathways to sustainability through scaling deep should expect intergenerational anxieties, latent violence, dissatisfaction and suspicion72.

Thus researchers are invited to situate themselves at the ‘margin’, acknowledge the structural marginalisation of oppressed peoples, and embrace discomfort by expecting and/or designing research encounters to be sites of ‘resistance’ at the margin72,73,74,75. Resistance centres the lived experiences of those at the margins, allowing for the surfacing and re-working of the colonial matrices of power in a way that can foreground the navigational creativity and radical possibility found at the margin73,75. Resistance allows for ‘Other’ stories to be heard, moving the researcher away from stories of pain and oppression towards the potential that hope and desire at the margin imply for just change72,74,76.

Desire is the counter-logic to the legacies of historical pain as wrought by colonialism and inequality in post-colonial societies74. It expands the horizon of personal and collective possibilities, not yet foreclosed by coloniality, for those situated at the margins and for the researcher74,76. In scaling deep at the margin, researchers thus open up spaces for the catalysis and display of the capacity for/of oppressed peoples to (re)imagine and (re)create just worlds and realities as a form of resistance to the dehumanising impulses of colonialism (76 p.g. 258).

When making space for resistance and desire at the margins, researchers acknowledge that scaling deep (and research on it) is sometimes less sure-footed, especially when confronted with uncomfortable encounters, uncomfortable knowledge and failure74,77,78,79,80. It is dependent on enacting a methodology that is ‘[…] more embedded and material…respectful of relations to people and land.’21 through e.g. compensating marginalised peoples for their time and presence as research sites and participants81. Decolonial scaling deep at the margins is, therefore, an emergent, seldom-complete endevour. It involves searching for decisive moments of action where structure and agency intersect82. It also involves sticking with and addressing these differential moments of discomfort, delay, resistance and silence, allowing the researcher to use such affective dissonance to initiate a deeper mode of engagement with communities that would otherwise remain elusive without such moments74,80,83.

Reflecting on scaling deep in Mitchells’ plain to coproduce a multifunctional stormwater pond

Here we present an analysis of the decolonial TD-research process where we explore the different modes and phases of coproduction from the perspective of ourselves as researchers, the community and the landscape. The results analysis is organised chronologically, centering on critical dynamics and pivots in the TD process.

Researchers researching solutions

Our focus was on the local scale, experimenting with the potential for harvesting stormwater through MAR and water quality improvement at the Fulham stormwater pond while simultaneously engaging with local residents on possibilities for making the pond multifunctional. We engaged with the City of Cape Town (CoCT) at a scoping level to understand the policy and practices around water resilience. We found that there was a need for more knowledge on how actual solutions such as nature-based repurposing of stormwater ponds play out on the ground; how this can be done in collaboration with local communities; and how local-scale Nbs solutions could become part of the larger water and nature governance structures.

Due to the ongoing impact of the 1960s and 70s forced removals of coloured communities from District 6 to Mitchells Plain (see Methods), as well as the continuing legacies of racial capitalism-via-apartheid in South Africa, many marginalised communities in South African cities like Cape Town are hyperlocalised spaces that are protected and policed by locals; they are sites of resistance, racial and class struggles, and more recently, xenophobic impulses as inequality widens84,85. As a team of nine researchers from different disciplines and positionalities (white, black and/or foreign researchers), we were aware of our positions on different axes of privilege/intersectionality, including being members of the modern university that has long been identified as a part of the colonial project86. As such, we were aware of the possible challenges with setting up real-life experiments in settings where we might not be accepted and where there could be safety/security concerns (e.g. installations could be stolen). Furthermore, we were aware that engaging with local residents in marginalised communities could be challenging as research activities would not necessarily contribute to addressing existing infrastructure and equity deficits. But early March 2020, we met with the local ward councillor to introduce the project and seek community buy-in for us to access and work in the area. We also met with administrators of a school that is adjacent to the pond as we saw the school and the children as key stakeholders.

In mid-March 2020, we held a public information session where we presented the project and collected scoping information on community perceptions/awareness of the Pond, as well as visions of what a repurposed multifunctional Pond could look like. Our initial observation was that the community viewed the pond with studied ambivalence. On one hand, it was not actively used as it had no amenities; however, much effort was put into deterring criminal elements and informal settlers via well-organised neighbourhood watch groups. In late March 2020, South Africa went into a COVID-19 lockdown, putting the project on a hiatus.

An unexpected impulse to scale-deep—the emergence of resistance

Permission was received from CoCT to conduct the experiment at the Pond (which is a CoCT ‘asset’) in early 2021 and June 2021 after COVID restrictions eased, the project recommenced. We tried to get in touch with the councillor, the school and the community members present at the first information meeting by sending out emails that recapped what the project was about, highlighting the next step of installing monitoring boreholes and that some scientists and contractors would be at the pond on a regular basis. However, we struggled to get in touch with all community members via email.

Subsequently, what we expected to be straightforward project initiation site visits turned into racially-heated encounters. On the day of borehole installations in late June 2021, two black researchers arrived first, along with the contractor crew. Locals showed up asking the researchers to leave, having seen a post on the community WhatsApp group that ‘…There are Africans walking around in the pond.’ The ward councillor’s arrival did not ease tensions. After the incident, the local prinicipal investigator (PI) of the project reached out to the councillor and locals for a meeting at the pond. This was a charged encounter where community members made clear that they were unhappy with having outside contractors and researchers working in their pond. The community were also frustrated with the lack of tangible benefits from the project. There were demands for more local involvement in the project than had been initially imagined.

After the meeting, a series of candid emails between community representatives and the research team further underscored resistance from local residents who wanted to know whether there would be skills transfer during the project as a way of empowering the community to take more responsibility for the Pond as well as pointed questions on budget availability. As highlighted by one resident in a terse email, ‘This project you are talking about should be for our community members and not people outside of Rondevlei[…] why was the community not consulted when a contractor was appointed because we have a variety of skills including construction within our community’.

With this pushback, the research project had become a site of unforeseen resistance. What the researchers saw as an ordinary pond for an experiment on the potential of NbS to support water resilience, was based on a limited accounting for the ongoing impacts of the legacies and associated traumas of apartheid and the implications this would have for planning, designing and implementing NbS interventions; an implicit assumption of society as a blank canvas, possibly emanating from our (privileged) position within the colonial power matrices as researchers. With their unequivocal refusal, the community placed before us an alternative to these assumptions: their own desire for deeper engagement with and through the experiment, on their own terms, in their own space. They countered our framing of the Pond experiment as a rational endeavour by foregrounding it as an expression of the ‘margin’: a space of ongoing exclusion pregnant with imagination, desire and hope. By doing so, the community brought a grammar of the margin to the fore, one that centres the ‘material debris of apartheid’87,88, its ongoing legacy and the anxieties related to dispossession; while also inviting a reflexive expansion of possibilities for the experiment. This provided an unexpected impulse for decolonial scaling deep at the margin.

Making space for empathy, resistance and desire

Reactions from the research team members to the heated encounters were varied tones of discomfort and frustration. As put by one member, ‘They obviously do not want us there…yes, I am black but not a criminal, so what is their problem? […] But I do understand their frustration in a way.’ We, therefore, took a step back through June and July 2021 to try to understand the situation. Email correspondence became more civil, and one resident highlighted that the community would be pleased with more hands-on involvement in the project via the hiring of local workers, and he looked forward to ‘[…] engaging because I believe we have the capacity to manage a project like this and not only supply the labourers.’ (G, 2021).

Ultimately residents were interested in moving beyond supportive roles towards more oversight/management of the operational aspects of the project, an exclamation of desire beyond resistance. The resistance set in motion a relational process of renegotiating the agency assigned to the researchers and community through scaling deep based on decolonial sensibilities. It also set the stage for the community’s articulation of desires for more agency and compensation as well as power over what happens in their environment.

The relational process meant we as researchers had to reflexively problematise our own assumptions; our gazes and poses, as well as our positionalities and intersectionalities as knowledge workers in a context of deep unresolved difference. Through this reflexivity we could engage in a relational process that demanded we place ourselves at the margin, a difficult yet necessary73 and possibly only space from which to work for socio-ecological transformation. On the other hand we had a project to run and report on, a pragmatism which pushed each of us to reconnect with the community again. We sought ways to build trust between ourselves and the community whilst managing risks; ensuring the community’s concerns were addressed so that the project could proceed. Even though the university’s procurement processes made it difficult to involve local service providers, we clarified what the budget was and found a way of giving some of the construction work to residents under the supervision of the project contractor during which skills and knowledge, e.g. sandbag construction were exchanged.

The project contractor had previous experience with NbS projects and working in informal and marginalised settlements. He became an important intermediary between the community and research team due to his ability to read the intimate dialectic grammars of the margin and privilege at play in the relational process. He set up a sandbag demonstration day with 30 community members at the Pond in late July 2021 as a platform to discuss the scope of works for the upcoming construction. Here too, residents emphasised that the community must benefit or else they would stop the project. The research team took a hands-off approach to how the community then organised who was employed for the construction days. We continued to build trust based on sustained daily contact with residents during the four construction weeks in August 2021, as well as by setting up a PaWS research WhatsApp group bringing together the community and researchers.

Community members opted to spread the paid construction work between four different groups of 6–8 workers so as to broaden the reach of the livelihood support benefit of the Pond construction period. They voted for a supervisor who would work parallel alongside the Contractor, as well as four local caterers to provide meals for the workers. They also set up different WhatsApp groups for coordination during the four weeks and added the researchers to each group; this proved to be more efficient in communication and coordination versus previous emails.

Doing transformation—physical engagement while unpacking complex intersectionalities

Construction of the Pond’s sandbag walls/overflow weirs took place in August 2021. With daily WhatsApp coordination and communication updates from the pond workers, we were able to track and understand how the young people working on the Pond were interacting with the space and the experiment. Banter was positive, ranging from reminders to latecomers, to uploads of photos showing the progress.

In this phase of our TD coproduction process, cultivating relationality was key to exploring the differences that emerged during the first encounters between researchers and the community. During the construction, researchers worked alongside the locals and got time to talk, e.g. on why they were so angry when they first spotted us at the pond. Locals told of how they worked hard to keep informal settlers (who are often black) from invading the pond with no help from the police. They also highlighted that although crime is a problem in parts of Mitchells Plains it was not in Rondevlei due to the community’s security efforts, without help from the city. It was clear the community did not trust the city or outsiders.

Additionally, whilst we considered the School adjacent to the Pond as a key interest in the Pond’s retrofit, some community members raised fears that the school (as a Muslim institution in a multi-faith community) would have ‘control’ over the Pond. Furthermore, the local community and its representatives is made up of different, potentially conflicting interests, which we needed to navigate carefully. There was also general concern within the community WhatsApp groups about the security of the sandbag installations as well as worries about littering at the Pond. However, we also found a strong crime prevention capacity in the community, which is an essential feature for retaining functional GI in Sub-Saharan cities89. There is a respected, active ‘Neighbourhood Watch’ programme, and residents look out for the installations at the Pond.

As relations thawed and the researchers and pond workers interacted more, the basis for the initial resistance became clearer. During the construction weeks, ‘jokes’ (i.e. 7 racial incidents in 22 working days) were made about one (black) researcher’s dark complexion. Such events prompted the researcher, the project partner and the local workers to have an informal dialogue about race. One of the residents pointed out that their reservations with ‘Africans’ working in their community were based on the coloured community also not being able to work in ‘African’ (black) areas whilst struggling to make ends meet in a country where their community feels neglected by the predominantly-Black national government.

It seems a large part of the community’s resistance stems from collective anxieties about dispossession, exclusion and neglect; resulting in an always-emergent resistance to perceived and actual dispossession by powerful actors like the CoCT, researchers and other outsiders. This was also evident from the recurring question by community members about where the water would go after it is harvested in the Pond. There were fears of the City coming to drill boreholes for water supply as had happened in other parts of Mitchells Plain during the 2015–2018 drought. As highlighted by one of the pond workers when asked what the Pond would represent to them in a few years, ‘We can now tell them [the kids] the reason the wall was built—it’s so that the water stays here, and the council cannot steal it from us.’ (Dv). Indeed, such fears of further dispossession harken to the forced removals of people-of-colour from District 6 to Mitchells Plain, as mentioned in the Discussion section.

Continuing with desire and hearing frog calls from the pond

During August 2021, as the construction of the pond proceeded and several months after, we monitored the WhatsApp dynamics. Beyond good-natured banter, the pond workers and wider community were surveilling the Pond: reporting littering, deliberate oil spills into the stormwater inlet, children damaging installations and delinquent behaviours by some users. In line with our hands-off approach, we moved from more steered involvement as originally envisaged at the start of the project towards more punctuated engagement where Whatsapp provided a forum for questions and mutual exchange of ideas about the Pond with the community.

From the start of the TD process in June 2021 and after the construction period, we saw evidence of enhanced social learning and ecological literacy as the Pond Workers and other community members posted photos of the changes to the landscape i.e. photos of flowers in bloom and stories about the endangered leopard toads as well as the changing wetland section of the pond. When asked what he now believed the purpose of the Pond was, one young man highlighted the multiple functions of the pond and the signs of enhanced biodiversity, saying, ‘[…] there’s this ecosystem over here, endangered species, there’s a lot going on here.’ (K).

The community also exhibited an enhanced sense of stewardship of the Pond by placing rocks demarcating the boundaries of the wetland section, thereby preventing the municipal contractor from mowing the wetland section of the Pond as part of the city’s maintenance operations. Another member of the Pond workers team also pointed to improved ecological literacy as well as an increased sense of ownership of the Pond by highlighting that ‘[…] we knew about this ecosystem, but now are able to talk about specifics. A board about this place […] to educate people on this space is important.’ (K). Along with enhanced ecological literacy, the pond workers gained new skills e.g. sandbag technology for construction.

During September 2021, the community and the school organised two planting days as part of celebrating Spring Day and Arbor Month. In an exhibition of empowered ecological agency, community representatives arranged for donations of indigenous plant seedlings from a local nursery, while the project contractor arranged for a talk by a well-known socio-environmental activist on the importance of indigenous plants for maintaining and enhancing the biodiversity of community green spaces like the Pond. In this instance, the community representatives and project contractor initiated and mediated an important encounter between one of the researchers and the ecological activist in a way that has supported the continued development of the project for the research team via network building. The two planting days generated interest in the Pond in the wider community as was reported by local newspapers. See the article at https://www.plainsman.co.za/news/indigenous-trees-planted-as-part-of-research-pilot-project-4c179898-1108-4c7b-8194-f704f4378c84.

Interviews with users of the Pond and adjacent households in late 2021 and 2022 clearly indicate that locals now have a more favourable view of the pond. They exercise there, children play there more often, and others walk their dogs there. The pond is greener and ‘louder’ than before, with an enhanced wetland patch in the middle from which deepened sounds of nature now emanate, including frog calls and birds. Perceptions of the Pond’s functionality have also changed discursively, especially among those who worked on its retrofitting; they now show sensitivity to birds and flowers and the site as an ecosystem, “The good thing is there is no more water that pools, it drains quickly […] now it’s (the Pond) a nice place to be.” (B and Za).

Centering the landscape—Moving from imagination to tangible action at the margins

A year after the retrofit works at the Pond, the main activities of the research team include maintenance work, such as addressing the problem of moles burrowing through the infiltration trench. Landscape design and amenity aspects have also been a key part of this later stage of the retrofit, including the commissioning of a painted Mural. The Mural process was intended as a Pond activation activity to empower the community, research team and landscape further by providing a place-making device which supports the Pond as a multifunctional landscape whilst building the public’s ecological literacy about the functions of the Pond and its contribution to water resilience.

The mural process, completed in December 2022, was facilitated by a popular Capetonian artist team where researchers, along with the community, were asked what we understand about the Pond, what we envision it could be and how we see it contributing to the community. During this visual harvesting segment of the mural painting process, residents highlighted visions of the Pond as a park with benches and trees for relaxation as well as generosity gardens to support community health and nutrition needs, thus empowering the Pond to be a crucial green space supporting community needs. On the other hand, there have been calls for it to be protected from vandalism, invasion and litter dumping, thus highlighting the centrality of security concerns.

Whilst we, as a research team, engaged in the experimental, physical alteration and the resultant water quality and quantity functions of the Pond, the community and city practitioners called for more observable changes to the landscape itself. This highlighted a shortcoming in our TD coproduction process: the engineering phase of the project proceeded faster and parallel to the landscape design research work resulting in a Pond whose hydraulic and quality function have improved ahead of the (still forthcoming) visual changes. For now, these have been limited to the landscape being greener and wetter in some parts, along with increased nature sounds. Other than the large mural, the Pond lacks amenity-supporting landscape changes which would further enhance how people experience and use it. This was also highlighted by stakeholders such as the ward councillor, ‘When is it (work on the Pond) going ahead, people feel more should be happening?’ (J); as well as a city practitioner, ‘The engineering seems fine enough, but the landscaping has been left to the end, and it (the Pond) doesn’t look so good.’ (T).

Where to go from here?

Whilst the mural is aimed at reframing the Pond’s agency as a landscape, another aspect of reframing the community and researcher agency has been the Pond’s maintenance needs after construction. From the outset, Pond maintenance post-project has been a concern of the research team, specifically how best to encourage community stewardship of the retrofitted Pond and what engagement approach is appropriate. The maintenance aspects have also been a concern and frustration for the community, along with questions of what should happen next in upgrading the amenity functions of the Pond as well as voicing their frustration with not knowing who should maintain it and how best to do so. As one Pond worker highlighted via WhatsApp, ‘[…] I would honestly like to know what is happening regarding the Pond, the plants should be watered, cleaning operations around the Pond, nothing of that is taking place and the plants are drying out […].’ (K).

Another concern was highlighted by a resident in an interview, ‘The City needs to come on board because if we pick up litter and clean the Pond we don’t want to have the rubbish pile up.’ (B) The same resident also underscored the community’s willingness to engage in maintenance, highlighting that the community needs a maintenance protocol ‘[…] to tell people what the maintenance plan is as well as when to come and maintain the Pond […] if there is a plan the community can do it […]’ (B). On the other hand, there also remains the issue of how different interests within the community could be modulated in ways that build an inclusive constituency around maintenance and addresses issues such as the dumping of oil and refuse at the Pond.

From the city’s perspective, the maintenance of a multifunctional pond presents an unfamiliar governance conundrum as it requires coordination between the city and the community, as well as between the city’s departments whose mandates intersect at the Pond. At the moment, the pond is a stormwater department’s asset, yet as a repurposed multifunctional pond, its maintenance needs will be more aligned to the Open Space management department. For now, maintenance has been through the city’s stormwater management department with subcontractors mowing the pond, and ad hoc litter collection by residents and the research team.

The question remains how a repurposed multifunctional pond can be maintained in a way that supports and links community efforts with the work of relevant different city departments. In response, the research team has discussed having a non-profit ‘Friends of…’ group set up to design, fund and operationalise a maintenance plan/landscape management plan. Such an organisation could tap into the City’s funding allocations at the ward level and possibly provide an avenue to link what’s happening at the Pond with relevant city departments in accessing Pond-specific services such as requesting ad hoc waste pick-up after maintenance activities.

Discussion

Scaling deep at the margins: why resistance and desire matter for decolonial praxis of nature-based solutions in the Global South

The aim of this article has been to reflect, using a decolonial lens, on the transdisciplinary research and coproduction processes of scaling deep at the margins characterising the experimental implementation of WSD as an NbS at the community scale in Cape Town. Our article builds upon intersecting literatures on socio-ecological transitions90, climate action, decoloniality, urban marginality and TD coproduction to present an analysis of TD-research-in-practice in a post-colonial city. While many studies exploring socio-ecological change through NbS, such as WSD, have hitherto concentrated on the Global North, our research demonstrates the dynamics of socio-ecological and technological climate action in contexts where the historical legacies of apartheid and colonialism continue to frame urban infrastructural realities and futures for many who remain marginalised. In this section, we distil from our reflections, insights on what we see as the key contours that characterise scaling deep at the margins as a transdisciplinary coproduction of NbS in the post-apartheid/colonial context of Cape Town.

First, our experience has highlighted the university’s situatedness within colonial power matrices, which if not interrogated with a decolonial lens may hinder the transformative potential of TD coproduction processes. Within a global knowledge economy, most funding mechanisms overlook practical interventions that might be deemed ‘development work’. This makes it difficult to find meaningful mechanisms for leveraging communities’ involvement at the project conceptualisation stage in ways that avoid overpromising and disappointing local communities. Furthermore, in our case the university procurement process (whose conditions for enrolment local service providers have found difficult to navigate), resulted in an outside contractor taking the lead in the operational aspects of borehole drilling and pond retrofitting. This highlights the continued structural exclusion of historically-marginalised citizens from gainful city-making processes. It also underscores the importance of decolonial sensibilities for researchers in contexts of deep difference, such as South Africa58. It shows how a TD process with transformative socio-ecological goals may unintentionally concede to the still-strong extractive and exclusionary impulses of coloniality that characterise the knowledge economy and production, especially in the Global South52,91.

Second, our study adds several insights to the call by Lam et al.27 and Woiwode et al.33, for socio-ecological research that explores ‘scaling deep’ as an amplification pathway in socio-ecological transitions. In contexts saddled with the unjust legacies of colonialism, experiments in socio-ecological transitions should concentrate on scaling deep first, before considering scaling -up or -out. This is predicated on the understanding that black, Indigenous- and other people-of-colour (BIPOC) in settler or post-colonial societies have traumatic intergenerational anxieties about violence, displacement, disinvestment and exclusion from urban infrastructures, including BGI. As such, NbS interventions that fail to account for the histories, capacities and contextual dynamics of different actors, and are not collaboratively conceived, implemented and governed by city departments, local communities and other stakeholders may further entrench inequality and bring in new forms of exclusion 63,92. Thus, in line with Smith76, we argue that to pursue TD coproduction as a transformative decolonial enterprise in contexts of continuing inequality, research on socio-ecological and technological change must scale-deep first, by reflexively finding and situating itself at the ‘margin’ as far and early as possible.

In addition to scaling deep at the margin, this paper argues for the importance of centring resistance and desire when pursing socio-ecological change through NbS in post-colonial cities, as do other studies of resistance to so-called ‘just socio-technical-ecological transitions’93,94. As we have shown, it is at the urban margin that marginalised peoples carve out agency for resistance, desire and alternative narratives about their socio-ecological realities and futures. In our case, the local community, a people historically disadvantaged and who continue to struggle daily at the margins of a post-colonial city, turned the encounter with us as researchers (and the TD process) and their own marginality into a ‘site of resistance and desire’ where the margin is intimately interwoven with impulses of power73,75,76. However, the discussions between researchers and locals during construction also reveal the deep complexity found in a post-apartheid city. The embodied positionalities and intersectionalities: be they of researchers, locals or of the city render the ‘margin’ itself a fluid construct, where, for instance, emergent- as well as negotiated- resistance in the form of racism and aggression served to also marginalise darker-skinned researchers initially.

To allay the resistance and anxieties that arose early in our TD process, we also trace how relationality became key to unlocking possibilities for working together as found by many studies on TD coproduction56,59. In the face of resistance, the research process had to slow down to allow for trust and relationship-building on the community’s terms, including allowing for self-organisation of the work to be done at the Pond. By exercising their collective agency through resistance, the community found ways to recalibrate the power differentials and unequal exchange on which much knowledge production is based. They were able to leverage what happens in their community, Pond and in the local environment on their own terms while to making us as researchers accountable too.

As such, making space for resistance to emerge and for desires to be articulated, can allow researchers and other stakeholders in contexts of inequality to begin the hard, risky work of re-working the contours of the colonial power matrix in ways that foreground a decolonial knowledge production process and possibilities for just and sustainable futures for all. The TD process of scaling deep at the margin also placed us as researchers in a position to begin to bridge the often-fraught relations between the City and the community. With empathetic listening and knowledge exchange, we could articulate needs, translate views, and widen our own positional boundaries by joining in the ‘navigational creativity’ the community had opened up when they turned our encounters into sites of resistance at the margins.

On the other hand, making space for resistance and desire also means resisting the impulse to frame socio-ecological action research as virtuous. Instead, it means allowing for the possibilities of failure when resistance is encountered and seeking generative insights thereof, as also found by Collins77 and Zielke et al.78. Our case highlights that scaling deep at the margin may always be an emergent, seldom-complete endeavour, and that (the threat of) failure is more productive when reflexively interrogated as a learning opportunity about what so-called ‘just and sustainable futures’ are (not) for different peoples.

We also found that at the heart of decolonial scaling deep at the margin in contexts of deep difference is the need for research with tangible outcomes and impacts. In our case, our research became more impactful when it was recalibrated beyond the aim of producing knowledge on the possibilities for water resilience through the multifunctional repurposing of a stormwater Pond, towards also supporting livelihoods through paid labour and skills transfer. The support for human wellbeing through improved amenities at the Pond remains another possible tangible impact of the project to be realised in the near future. However, questions remain about how to initiate collaborative maintenance and stewardship of the multifunctional Pond across CoCT’s departments as well as in collaboration between the CoCT and the local community. As such, one of the limitations of our approach was the lack of clear linkages between the local-scale activities we engaged in, with city-level infrastructure governance dynamics. In this respect we propose future research that explores how social relations between local communities, city departments and non-profits can be best constituted to make the use of the affective and physical resources available for governing multifunctional landscapes in a post-colonial city.

Our case speaks to the importance of socio-ecological research praxis in post-colonial cities that privileges the real-world material production of NbS as improved and accessible green infrastructure areas where safe green spaces remain inaccessible or present as a security risk for many in marginalised communities. It also speaks to the need for a decolonial scaling deep TD-research processes that are cautiously ambitious, seeking not only pathways to policy impact but, more importantly, avenues for material impact in showcasing possibilities for NbS coproduction best practice that is situated at the margin in cities of historical and ongoing deep difference. By scaling deep and making space for resistance and desire at the margins, researchers make space for a studied, if radical, relinquishing of hegemonic power over infrastructural realities and futures in contexts of deep unresolved difference, such as Cape Town. Finally, we contend that sustainability transitions in the Global South may be more productively understood as contested, emergent and seldom-complete endeavours in which justice should remain the goal.

Methods

The Universities of Cape Town (Future Water Research Institute) and Copenhagen partnered on a DANIDA-funded research project entitled ‘Pathways to water-resilient South African cities’ (PaWS) that aims to ‘… generate knowledge on the physical and institutional integration of decentralised nature-based solutions into the urban water cycle.’ It combines physical experimentation and reflexive social learning processes with an exploration of governance aspects required to facilitate sustainability transitions towards water-sensitive futures. The physical experimentation focused on repurposing a stormwater detention pond in Mitchell’s Plain, Cape Town, for the treatment and harvesting of surface runoff through Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR). MAR is a process where groundwater is replenished by purposefully infiltrating or pumping water into an aquifer. This provided a platform for engaging with local residents, exploring added functions for the repurposed pond area e.g. biodiversity, amenity and livelihood support. Informed consent was obtained for all interviews conducted in the study. The study complies with the Ethics in Research (EiR) approval granted for the study by the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment at the University of Cape Town in September 2019. Participation in PaWS project activities was on a voluntrary basis and informed consent was obtained from participants for all interviews conducted in the study.

Context and case site

The pond is situated in Rondevlei Park in Mitchells Plain, a meduim-density residential neighbourhood of mostly single-storey houses, adjacent to a school. Mitchells Plain (43.76 km²) is a low-lying, sandy area, 25 km southeast of Cape Town centre. It was developed in the 1960s to 1970s to provide housing for coloured people—victims of forced removal due to the implementation of the Groups Areas Act85. In 1968, two thousand (mainly coloured) families were moved to Mitchell Plains from District Six in the inner city of Cape Town as it was declared a whites-only area85. The dislocation dissolved kinship and community ties and resulted in unemployment, crime and other social problems in the area which still persist95 (Fig. 1).

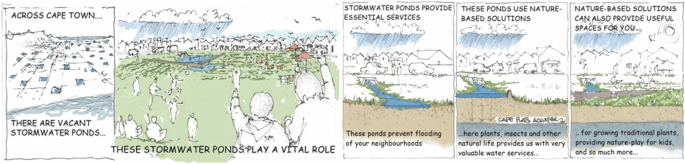

Comic strip presenting the idea behind PaWS project to local community (Comic by J. Mclachlan).

The physical experiment

The detention pond is an excavated green space connected to a stormwater system with two inlets and an outlet. Rainfall-runoff is directed to the pond via the piped stormwater network as a means of slowing and confining the flow before releasing it to the main stormwater pipeline (trunk) and leaving the pond to dry out, thereby easing urban flooding. Please refer to McLachlan et al.96, for more information. (Fig. 2).

a Residents positioning the PVC sheet on the berm. b Assembling the sandbag berm.

The PaWS experiment sought to re-design the pond and create infiltration areas to promote MAR while incorporating landscaping elements to promote the pond’s amenities and biodiversity. A low-cost technical re-design was chosen to improve stormwater quality and maximise the groundwater recharging while ensuring the pond achieves its core function of handling stormwater before release into the city’s stormwater drainage system. The complexity of the technical interventions was kept low so that local residents and contractors could take responsibility for management/maintenance. The technical design considered four critical components (a) energy dissipaters in the form of ripraps, (b) litter traps fashioned as rock check dams, (c) an infiltration swale and (d) a sandbag berm and outlet weirs (Fig. 3).

Multifunctional retrofitted stormwater pond – The retrofitted stormwater Pond in Rondvlei Park featuring inlets, ripraps, rock check dams, infiltration swale, outlet weirs and the outet.

Engagement methods

Please see Table 1 for a listing of the engagement activities between 2020–2022; from initial information meetings on the water experiment in 2020, to crisis meetings on whether (and how) to involve locals in the construction of the water experiment, to the planting days and mural painting. It is this ’engagement’ process which we unfold and reflect on throughout the paper. We have also conducted informal talks with locals during and after construction, semi-structured interviews, surveys, workshops and focus group discussions on perceptions and usage of the pond area, understandings of its functions and multifunctional possibilities as well as understanding of socio-ecological aspects of the Pond area.

In total 24 semi-structured interviews were conducted, on how the pond area was used and perceived before and after the construction of the water experiment. The participants in the construction were also interviewed about their experiences from the construction process and what they learned etc. Further, leaders of associations and the councillor were asked to reflect on the agency of the local community and give background into the organisation and mobilisation of the community. City officials were interviewed and a workshop was conducted, which included a field trip to the Pond site. City officials were asked for their thoughts on the potential for multifunctional repurposing of stormwater ponds. The various activities in this two-year engagement process provide ‘data’ for this paper in the form of meeting notes, summaries, and photos of all various activities. Another major data source is WhatsApp communication. During the construction of the infiltration trench for MAR and the installation of monitoring boreholes in June 2021– September 2021 WhatsApp groups were set up. The WhatsApp conversations and posts form an important basis for understanding the changes in perceptions of the area; how it is talked about and portrayed in photos. Email correspondence between researchers and locals on coordination of activities and wishes for the area is also a data source. Please see the Supplementary Methods material attached.

Responses