SENP1-mediated deSUMOylation of YBX1 promotes colorectal cancer development through the SENP1-YBX1-AKT signaling axis

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide, with an estimated 1.9 million new cases diagnosed annually. Approximately 900,000 deaths are attributed to the disease annually [1,2,3]. At present, the most common treatment strategy for CRC involves surgical resection combined with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy [4, 5]. However, these therapeutic interventions have yielded only limited improvements in patient outcomes. Therefore, a deeper exploration and understanding of the key molecules and pathways that drive CRC progression are warranted, which will not only facilitate the identification of novel targets for the early diagnosis and treatment of CRC patients, but also provide a solid theoretical foundation for the development of effective CRC treatment strategies.

SUMOylation is one of the most important protein translational modifications (PTMs), by which small ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO) is conjugated to the Lys residue of substrate proteins, and it confers diversity and complexity to biological functions of proteins under different physiological and pathological conditions [6,7,8,9]. Under normal physiological conditions, the protein SUMOylation/ deSUMOylation cycle is in equilibrium, while the abnormal function of SUMO pathway and related regulatory enzymes are involved in the occurrence and development of many cancers [6,7,8,9]. As one of SUMO-specific proteases (SENPs), SENP1 catalyzes protein deSUMOylation on a pool of different substrates, thereby regulating the malignant process of a variety of tumors including lung cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and liver cancer [10,11,12,13,14].

In most cases, SENP1 is considered to be an oncogenic protein [10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. But it has also been reported that SENP1 can inhibit the development of malignant tumors by regulating the development and function of immunosuppressive myeloid-derived suppressor cells [17]. More interestingly, SENP1 was reported to act as a tumor promoter by deSUMOylating RNF168 in HCT116 cells [16], whereas Choi et al reported that SENP1 could selectively mediate DKK-induced deSUMOylation of TBL-TBLR1 and suppress the tumorigenicity of SW480 cells [18]. Undoubtedly, the complexity of SENP1 function in carcinogenesis lies in its capacity to differentially target and deSUMOylate a diverse array of proteins, thereby influencing cancer cell dynamics. Therefore, it is of great research significance to further clarify the function of SENP1-mediated deSUMOylation of specific substrate proteins in CRC.

The Y box binding protein 1 (YBOX1, also known as YBX1) is a multifunctional DNA- and RNA-binding protein with an evolutionarily ancient and conserved cold shock domain [19,20,21,22]. YBX1 is mainly distributed in the cytoplasm, but can also shuttle in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Abnormal expression of YBX1 contributes to the tumorigenesis and metastasis of cancer and is closely linked with poor patient outcome. Cumulative evidence suggests that YBX1 functions as RNA/DNA binding protein in modulating target mRNA transcription and stabilization, thereby regulating cancer cell behaviors, such as cell proliferation, cell cycle progression, stemness, migration and invasion, DNA damage repair, autophagy, tumor immunity, and multidrug resistance [19,20,21,22]. Furthermore, YBX1 plays also a significant role in the activation of NF-κB pathway in CRC, and this function stems from IL-1β-mediated Ser-176 phosphorylation of YBX1 and PRMT5-mediated its Arg-205 methylation [19, 20]. However, the other PTMs of YBX1 on the regulation of its biological functions in CRC is yet to be explored.

In the present study, we have dissected the effects of SENP1-mediated YBX1 deSUMOylation on CRC progression and unveiled its underlying mechanism. We applied SUMO modification-based omics and protein interacting omics to search for SENP1-mediated deSUMOylation target proteins and identified YBX1 as a novel deSUMOylation substrate of SENP1. SENP1 bound to YBX1 protein to catalyze the deSUMOylation of YBX1. DeSUMOylated YBX1 at its K26 site activated the AKT pathway by recruiting more DDX5 to form the YBX1-DDX5 complex, thereby promoting CRC progression. Moreover, the increased expression of SENP1 and YBX1 was in CRC and associated with poor outcomes of patients. Together, our work indicates targeting SENP1-YBX1-AKT signaling axis as a potential effective strategy for the treatment of CRC.

Results

Identification of YBX1 as one deSUMOylation substrate of SENP1

Large-scale MS-based proteomic approaches are challenging to identify SUMOylated proteins due to their variable stoichiometry and the presence of long C- terminus polypeptides within the SUMO molecule that complicates the interpretation of the corresponding product ion spectra [23, 24]. Herein, we developed a mutant SUMO1T95K tagging method to overcome this problem, which involved the introduction of a mutant SUMO1 with a C-terminal Lys-C cleavage site by transfecting plasmids pHis6-SUMO1T95K (T95 was mutated to K) into HEK293T cells to enrich His6-SUMO1T95K-tagging SUMOylated proteins, and the introduction of lysine (K) at position 95 had no influence on the original SUMOylation patterns (Supplementary Fig. S1A, Supporting Information).

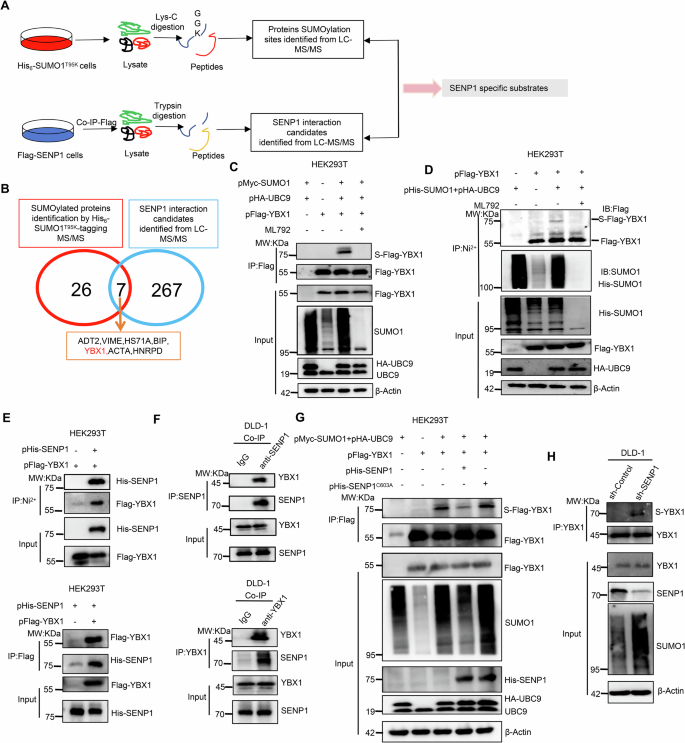

We adopted a LC-MS/MS strategy by combining SUMO modification and protein interaction analysis to systematically identify the potential deSUMOylation substrates mediated by SENP1 protein (Fig. 1A). The substrate molecules of SENP1 must meet the following two conditions simultaneously. The proteins should undergo SUMO modification and also interact with SENP1. So far, this combinatorial screening strategy will greatly enhance the accuracy and reliability of identifying SENP1-mediated targets. Applying the His6-SUMO1T95K-tagging SUMOylation analysis, we identified a total of 26 potential SUMOylated proteins and 34 SUMOylation sites (Table 1, Supporting Information). Meanwhile, 267 SENP1- interacting proteins were identified by MS/MS (Table 2, Supporting Information). Through the integrated analysis of these two MS/MS datasets, we preliminarily screened YBX1 protein as a novel candidate substrate protein of SENP1 (Fig. 1B, Supplementary Fig. S1B–D).

A A simple flow diagram for LC-MS/MS identification of SENP1 targeting substrates using two proteomics strategies. The His6-SUMO-1T95K-tagging SUMOylated proteins were enriched by IP using Ni2+-NTA agarose beads, digested with the enzyme Lys-C, and the “GGK”-containing peptides was identified by LC-MS/MS to screen the SUMOylated proteins and sites (Top). Meanwhile, the SENP1 binding proteins were concentrated through Co-IP using anti-Flag magnetic beads, and performed trypsin digestion to run LC-MS/MS (Bottom). B The 7 overlapped proteins between the 26 SUMO-modified proteins and the 267 SENP1-interacting partners were the potential SENP1-mediated substrate proteins, and from which the YBX1 was selected to investigate its interaction with SENP1. C, D The SUMOylation level of YBX1 was compared in response with UBC9/SUMO1 enhancement or SUMOylation inhibitor (ML792) treatment. HEK293T cells were co-transiently transfected with pFlag-YBX1, pHA-UBC9 and pMyc-SUMO1 or pHis-SUMO1 plasmids as indicated for 24 h, then cells were treated with 10 μM ML792 for 24 h. The Flag-tagging YBX1 (Flag-YBX1) was enriched by IP assay using anti-Flag magnetic beads (C) or Ni2+-NTA agarose beads (D) to detect the SUMOylated YBX1 level. E Co-IP assays confirmed the interaction between His-tagging SENP1 (His-SENP1) and Flag-YBX1 in HEK293T cells transfected with indicated plasmids. F Co-IP assays indicated the interaction between cellular endogenous SENP1 and YBX1 in DLD-1 cells. G IP assays confirmed SENP1-induced YBX1 deSUMOylation was dependent on SENP1 deSUMOylation enzyme activity in HEK293T cells that were transiently transfected with pFlag-YBX1, pHA-UBC9, pMyc-SUMO1, pHis-SENP1 or pHis-SENP1C630A (C603 was mutated to A) plasmids at various combinations as indicated. H SENP1 depletion enhanced YBX1 SUMOylation in DLD-1 cells that were stably transfected with short hairpin RNA targeting to SENP1 (sh-SENP1). sh-Control short hairpin RNA targeting to empty vector, S-Flag-YBX1 SUMOylated Flag-tagging YBX1, S-YBX1 SUMOylated YBX1, IP immunoprecipitation, IB immunoblot, Input Same account of cell lysate to load.

HEK293T cells were transiently co-transfected with pMyc-SUMO1, pHA-UBC9 and pFlag-YBX1 plasmids to validate the SENP1-acting substrate protein of YBX1. After transfection for 48 h, the Flag-tagging YBX1 (Flag-YBX1) protein was enriched by IP using Anti-Flag magnetic beads. The SUMOylation of the ectopic YBX1 was detectable in cells co-transfected with pFlag-YBX1, pMyc-SUMO1 and pHA-UBC9 plasmids (Fig. 1C, lane 3) but not in cells co-transfected with pMyc-SUMO1 and pHA-UBC9 plasmids (Fig. 1B, lane 1) or only pFlag-YBX1 plasmids transfection (Fig. 1C, lane 2). YBX1 SUMOylation was impaired by SUMOylation inhibitor ML-792 treatment (Fig. 1C, lane 4).

Similarly, we also transiently transfected pFlag-YBX1 along with pHis-SUMO1/pHA-UBC9 plasmids in HEK293T cells, and following purification of His-tagging SUMO conjugates with Ni2+-NTA agarose beads, to capture the His-SUMO1-tagging YBX1 protein. Consistent with the above results, the most obvious His-SUMO1-tagging YBX1 band was visible only in the cells co-transfected with pFlag-YBX1, pHis-SUMO1 and pHA-UBC9 plasmids, but not in the cells from the other groups (Fig. 1D). These results indicated that YBX1 was obviously modified by SUMO1 conjugation.

We further determined the potential regulation of SENP1 on YBX1 under their ectopic overexpression or cellular natural level through Co-IP assays. Indeed, the ectopic overexpression of SENP1 and YBX1 interacted with each other in HEK293T cells (Fig. 1E). Moreover, this interaction between cellular natural level of SENP1 and YBX1 in DLD-1 cells was also observed using SENP1 antibody or YBX1 antibody to pull down each other (Fig. 1F).

Furthermore, we measured SENP1-mediated YBX1 deSUMOylation in HEK293T and DLD-1 cells. The exogenous plasmid pHis-SENP1 or pHis-SENP1C630A (C603 was mutated to A) was co-overexpressed with pFlag-YBX1, pHis-SUMO1, and pHA-UBC9 plasmids in HEK293T cells (Fig. 1G). The endogenous SENP1 was stably knocked down by short hairpin RNA (shRNA) interference in DLD-1 cells (Fig. 1H). Consistent with its deSUMOylating effect on YBX1, silencing the endogenous SENP1 enhanced the SUMOylated YBX1, while the overexpression of wild-type His-tagging SENP1 (His-SENP1) abrogated YBX1 SUMOylation compared with the inactive His-SENP1C603A expression (Fig. 1G, H).

We also further verified whether the binding of SUMO1 to YBX1 mainly occurred at K118, which was identified as a putative SUMO site in SUMO proteomic experiments. HEK293T cells were co-transfected with pMyc-SUMO1, pHA-UBC9, and pFlag-YBX1 or pFlag-YBX1K118R (K118 was mutated to R) plasmids for 48 h, and total cellular proteins were subjected to enrich the target Flag-tagging proteins with anti-Flag magnetic beads, following detected by western blotting with an anti-SUMO1 antibody. Actually, the SUMOylated degree of the mutant Flag-YBX1K118R showed similar as the wild-type Flag-YBX1 (Supplementary Fig. S1E, Supporting Information), indicating that except to the K118 site, YBX1 should contain other key SUMOylation sites.

K26 is one key SUMOylation site of YBX1

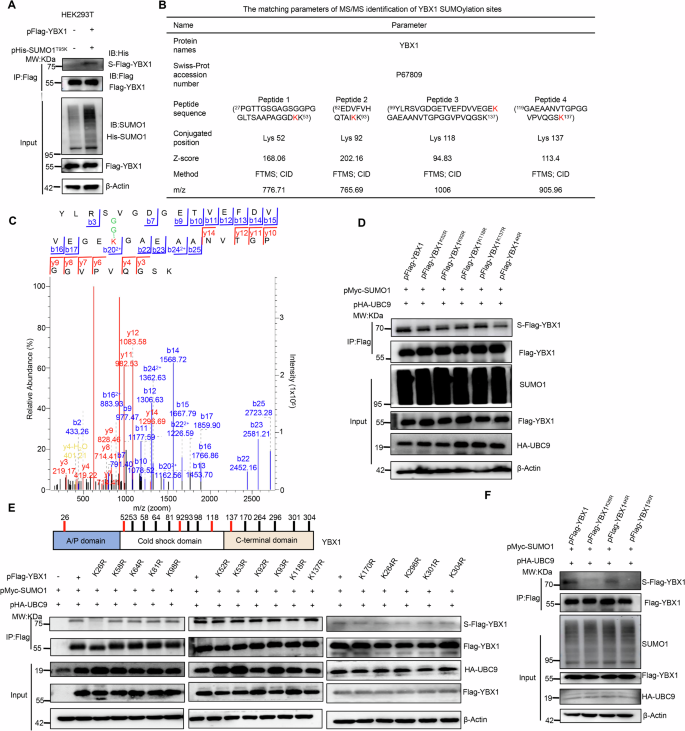

Subsequently, we identified the SUMOyaltion sites of YBX1 referencing our previous His-SUMO1T95K-tagging MS/MS approach [23]. Thus the plasmids pFlag-YBX1 and pHis-SUMO1T95K were simultaneously co-transfected into HEK293T cells to identify the YBX1 SUMOyaltion sites by MS/MS analysis again. Before MS detection, we confirmed that the YBX1 protein could also be modified by mutant SUMO1T95K (Fig. 2A). In addition to the K118 site (Fig. 2C), the K52, K92 and K137 sites of YBX1 were identified with undergoing SUMOylation modifications, as shown in Fig. 2B, C.

A YBX1 was modified by the exogenous His-tagging SUMO1T95K (His-SUMO1T95K) protein. Under co-overexpression of Flag-YBX1 with His-SUMO1T95K in HEK293T cells, the Flag-YBX1 was enriched by IP using anti-Flag magnetic beads to detect the SUMOylated YBX1 level. B The K52, K92, K118 and K137 residues of YBX1 were identified as the SUMOylation sites by MS/MS. C The MS/MS spectrum of one peptide (YLRSVGDGETVEFDVVEGEK118GAEAANVTGPGGVPVQGSK) from YBX1 whose K118 was conjugated with SUMO in FTMS/CID fragmentation mode. D The levels of SUMOylated YBX1 were significantly reduced in the four K sites-mutant (4KR) YBX1 with the simultaneous K52R/K92R/K118R/K137R mutation. HEK293T cells were co-transiently transfected with pHA-UBC9, pMyc-SUMO1 and pFlag-YBX1 (or each of pFlag-YBX1K52R, pFlag-YBX1K92R, pFlag-YBX1K118R, pFlag-YBX1K137R, pFlag-YBX14KR) for 48 h, and cell lysates were performed IP to capture Flag-YBX1 to detect the SUMOylated YBX1 level. E The K26 residue of YBX1 was identified being the major SUMO modification site. Top: Diagram for domain organization of YBX1 and the locations of all K residues. Bottom: Different single K-point mutants of YBX1 were transfected into HEK293T cells as indicated to measure YBX1 SUMOylation level. F The SUMOylation level of YBX1 was almost completely abolished in the five K sites-mutant (5KR) of YBX1 with the simultaneous K26/K52R/K92R/K118R/K137R mutation. HEK293T cells were co-transiently transfected with pHA-UBC9, pMyc-SUMO1 and pFlag-YBX1 or each of pFlag-YBX1K26R, pFlag-YBX14KR, pFlag-YBX15KR. After 48 h later, cell lysates were extracted to capture Flag-YBX1 and detect the SUMOylated YBX1 level. S-Flag-YBX1 SUMOylated Flag-tagging YBX1, S-YBX1 SUMOylated YBX1, IP immunoprecipitation, IB immunoblot, Input Same account of cell lysate to load.

We further created single SUMOylation residue mutation of the other three sites, including K52R, K92R and K137R, and all the four sites-mutation (K52R/K92R/K118R/K137R, 4KR) plasmid of YBX1, then transfected these mutation plasmids into HEK293T cells to validate SUMOylation level change of YBX1. As results, the SUMOylation level of the single mutant Flag-YBX1K52R, Flag-YBX1K92R, Flag-YBX1K118R, and Flag-YBX1K137R was similarly as the wild-type Flag-YBX1 (Fig. 2D). But the SUMOylated YBX1 level dramatically decreased in the mutant Flag-YBX14KR samples (Fig. 2D, Lane 6), which indicated that the SUMO modifications really generated on these 4 sites (K52, K92, K118, and K137) of YBX1.

Considering that SUMOylation typically occurs on lysine residues of the substrate, in fact the YBX1 protein totally contains 16K residues, including K26, K52, K53,K58, K64, K81, K92, K93, K98, K118, K137, K170, K264, K293, K301 and K304. We therefore separately mutated all K residues to R in the YBX1 protein, and assessed the SUMOylation status of each mutant protein. Excitingly, only the mutant Flag-YBX1K26R caused a significant decline in the total YBX1 SUMOylation level (Fig. 2E, Lane 3), which indicated that K26 was the major SUMOylation site of YBX1 protein. Moreover, the K26R/ K52R/ K92R/ K118R/ K137R five-mutation (5KR) of YBX1 exhibited the lowest level of SUMO modification among all YBX1 variants, almost completely abolishing the SUMOylated YBX1 level (Fig. 2F, Lane 4). Thus, K26, K52, K92, K118 and K137 are sites of YBX1 SUMOylation, among which K26 is the predominant SUMOylation site.

Elimination of YBX1 SUMOylation at K26 contributes YBX1 binding with DDX5 protein to activate AKT pathway

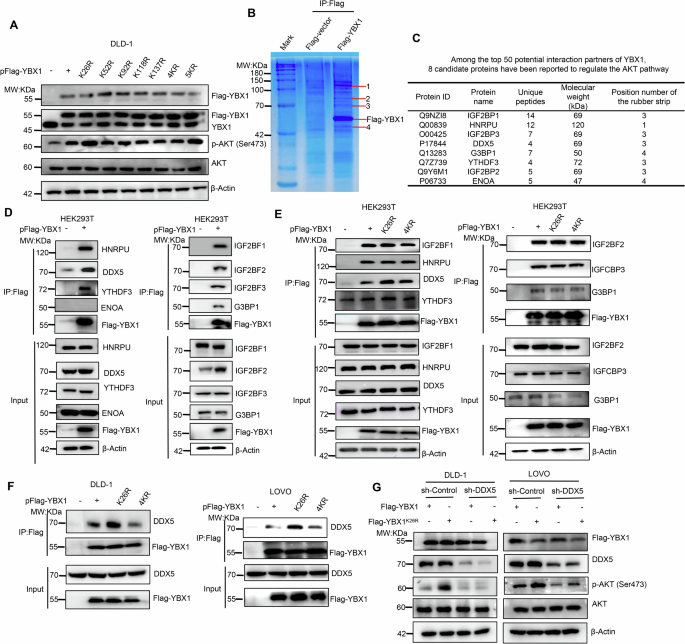

Given that YBX1 is an oncogenic factor in CRC through activating AKT pathway [22], therefore we would explore whether SUMOylation of YBX1 is involved in AKT signaling regulation. Consistent with a previous report [22], YBX1 knockdown significantly down-regulated the phosphorylation level of AKT and effectively inhibited CRC cell proliferation, colony formation, and migration (Supplementary Fig. S2A–D, Supporting Information). Subsequently, we separately transfected pFlag-YBX1, pFlag-YBX1K26R, pFlag-YBX1K52R, pFlag-YBX1K92R, pFlag-YBX1K118, pFlag-YBX1K137, pFlag-YBX14KR or pFlag-YBX15KR plasmids into DLD-1 cells to further examine the effect of each K mutation on AKT phosphorylation (p-AKT). Compared with Flag-YBX1, the overexpression of Flag-YBX1K26R or Flag-YBX15KR, but not the other mutants, significantly promoted AKT phosphorylation in DLD-1 cells (Fig. 3A), which suggested that YBX1 SUMOylation at K26 may be the only critical site for regulating the cancer-promoting function of YBX1.

A Effects of YBX1 and its mutants on AKT signaling in DLD-1 cells transfected with indicated plasmids. B YBX1-binding proteins were enriched from total lysates of HEK293T cells with over-expression of Flag-YBX1 with anti-Flag magnetic beads, separated by SDS-PAGE and stained by Coomassie brilliant blue. The specific binding protein bands (shown as arrows) were subjected to MS/MS analysis. C The MS/MS identification parameters of YBX1 and its eight candidate binding partners, including IGF2BP1, HNRPU, IGF2BP3, DDX5, G3BP1, YTHDF3, IGF2BP2 and ENOA proteins. D Interaction of YBX1 with its eight candidate binding partners (GF2BP1, HNRPU, IGF2BP3, DDX5, G3BP1, YTHDF3, IGF2BP2 and ENOA) was validated in HEK293T cells transfected with indicated plasmids. E Interaction of YBX1K26R or YBX14KR with IGF2BP1, HNRPU, IGF2BP3, DDX5, G3BP1, YTHDF3, IGF2BP2 was compared to that of the wild-type YBX1 in HEK293T cells transfected with indicated plasmids. F The interaction between DDX5 with YBX1, YBX1K26R, YBX14KR was measured in CRC cells transfected with indicated plasmids. G Flag-YBX1 or Flag-YBX1K26R overexpression had influence on p-AKT level in CRC cells stably transfecting with sh-DDX5. IP immunoprecipitation, Input Same account of cell lysate to load, sh-Control short hairpin RNA targeting to empty vector, sh-DDX5 short hairpin RNA targeting to DDX5.

As the cellular localization and stable expression of YBX1 protein were closely related with the activation of AKT pathway in CRC [22], we wondered whether SUMOylation was required for the cellular localization and stability of YBX1 protein to activate AKT pathway. In fact, SUMOylation did not affect stability and cellular localization of YBX1 (Supplementary Fig. S3A–C, Supporting Information). Since SUMOylation usually affected protein-protein interactions, we then captured Flag-YBX1 and its associated proteins from HEK293T cell lysates by Co-IP (Fig. 3B), and the complex was subjected to rounds of liquid chromatography and high-throughput mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The YBX1-binding protein complex analysis identified 167 potential YBX1-interacting proteins (Supplementary Table 3, Supporting Information).

Some identified YBX1-binding partners overlapped with the literature reports-based AKT pathway regulators, including IGF2BP1, HNRPU, IGF2BP3, DDX5, G3BP1, YTHDF3, IGF2BP2 and ENOA [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] as the top hit among the 50 potential YBX1 interactors (Fig. 3C). We further confirmed that YBX1 could interact with seven proteins, including IGF2BP1, HNRPU, IGF2BP3, DDX5, G3BP1, YTHDF3 and IGF2BP2 (Fig. 3D). Additionally, further studies indicated that abolishing SUMOylation at K26 only promoted the interaction between YBX1 and DDX5, but K26 mutation had no influence on the binding of YBX1 to the other six proteins (Fig. 3E). Compared with the Flag-YBX1 protein (Fig. 3E, F, Lane 2), Flag-YBX14KR protein bound an equivalent amount of DDX5 (Fig. 3E, F, Lane 4), whereas the mutant Flag-YBX1K26R protein bound more DDX5 protein (Fig. 3E, F, Lane 3), which indicated that the binding ability of YBX1 to DDX5 was mainly inhibited by YBX1 SUMOylation at K26, while other SUMOylation sites of YBX1 had no significant effect on it.

We transiently transfected pFlag-YBX1 or pFlag-YBX1K26R plasmids into DLD-1 or LOVO cells with stable knockdown of endogenous DDX5 to determine whether the SUMOylation-mediated interaction of YBX1 with DDX5 changed the biological function of YBX1. Bioinformatics analyses revealed that DDX5 was highly expressed in tumor tissue of CRC patients (Supplementary Fig. S4A, Supporting Information). Consistent with these analyses, IHC staining of CRC samples confirmed the higher abundance of DDX5 in CRC tissues compared with the adjacent normal tissues (Supplementary Fig. S4B, Supporting Information). And patients with higher DDX5 expression had shorter overall survival time (Supplementary Fig. S4C, Supporting Information). Moreover, DDX5 knockdown significantly down-regulated the level of p-AKT and effectively inhibited CRC cell proliferation, colony formation, and migration (Supplementary Fig. S4D–I, Supporting Information). Interestingly, the p-ATK level in YBX1K26R-overexpressing cells was significantly higher than that in YBX1-overexpressing cells (Fig. 3G, Lane 1 VS Lane 2). Under DDX5-knockdown cells, there was no significant difference of p-ATK level between YBX1 and the mutant YBX1K26R expression status (Fig. 3G, Lane 3 VS Lane 4), which demonstrated that SUMOylation regulated YBX1-invovled in AKT signaling in a DDX5-dependent manner. Together, YBX1 deSUMOylation at K26 enhanced YBX1 binding to DDX5, thereby inducing the activation of p-AKT.

Abolishment of YBX1 SUMOylation at K26 promotes CRC tumorigenesis by activating AKT phosphorylation

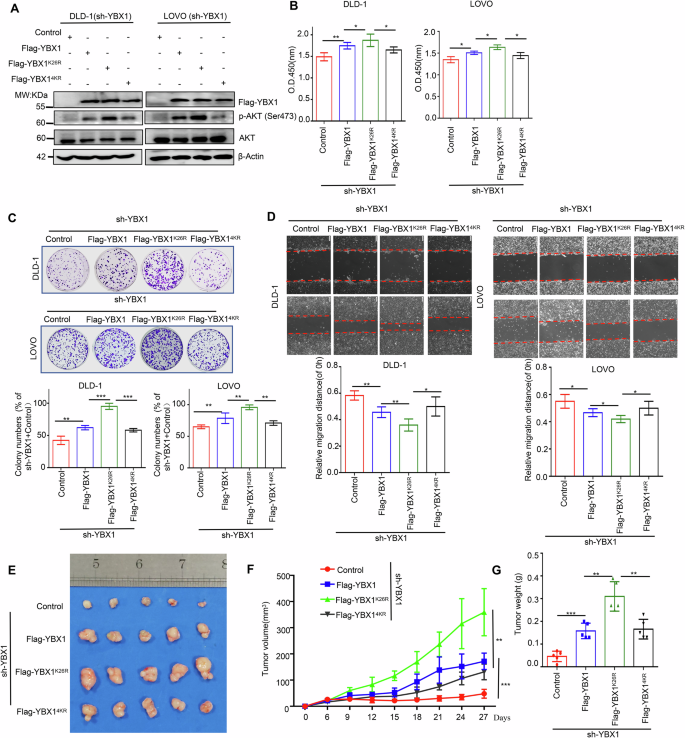

Next, DLD-1 and LOVO cells with stable knockdown of endogenous YBX1 were re-overexpressed Flag-YBX1, Flag-YBX1K26R or Flag-YBX14KR to investigate role of YBX1 SUMOylation in CRC tumorigenesis. Consistent with the above results, Flag-YBX1K26R expression significantly promoted p-AKT in YBX1-knockdown DLD-1 and LOVO cells compared with Flag-YBX1 and Flag-YBX14KR-expressing cells (Fig. 4A). In addition, the CCK-8 assay, colony formation assay and wound healing assay revealed that abolishing YBX1 SUMOylation at K26 enhanced YBX1 cancer-promoting ability in CRC. Compared with Flag-YBX1 or Flag-YBX14KR, the re-overexprssion of Flag-YBX1K26R significantly promoted cell proliferation, clone formation, and migration of CRC cells with YBX1 knockdown (Fig. 4B–D).

A Flag-YBX1K26R, or Flag-YBX14KR overexpression had influence on p-AKT level in YBX1-knockdown CRC cells. B Cell viability was compared in Flag-YBX1K26R or Flag-YBX14KR-expressing CRC cells under the endogenous YBX1 knockdown. All data presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. C Cell proliferation capacity was compared in Flag-YBX1K26R or Flag-YBX14KR-expressing CRC cells under the endogenous YBX1 knockdown. Representative images of the colony formation of the indicated cells in top and quantification of clone numbers in bottom. All data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. D Cell migration capacity was compared in Flag-YBX1K26R or Flag-YBX14KR-expressing CRC cells under the endogenous YBX1 knockdown. Representative images of the wound healing of the indicated cells in top and quantification of clone numbers in bottom. All data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Scale bar: 100 μm. E–G The subcutaneous tumor capacity was compared in Flag-YBX1K26R or Flag-YBX14KR-expressing CRC cells under the endogenous YBX1 knockdown. Tumor images (E), volume (F), and weight (G) were shown. Data were presented as the mean ± SD (n = 5 mice). Control Flag-vector, sh-YBX1 short hairpin RNA targeting to YBX1. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

We further verified associations of CRC growth with YBX1 SUMOylation in xenograft nude mouse model. 5 ×106 CRC cells for each group were inoculated into the right flank of nude mice. About 6 days after injection, the tumors in each group were obviously palpable with 35 mm3, and subsequently the tumor size was totally monitored for seven times from then on. Under YBX1- knockdown xenograft tumors, the overexpression of Flag-YBX1K26R significantly promoted xenograft tumor growth compared with Flag-YBX1 and Flag-YBX14KR-expressing xenograft tumors (Fig. 4E–G). At 27 days of inoculation, the tumor volume and weight of the overexpression of Flag-YBX1K26R (359.3 ± 98.9 mm3, 0.31 ± 0.07 g) was the largest and heaviest compared with Flag-YBX1 (171.7 ± 36.5 mm3, 0.16 ± 0.04 g) and Flag-YBX14KR-expressing xenograft tumors (131.4 ± 32.9 mm3, 0.17 ± 0.05 g) (Fig. 4F, G). Taken together, our in vitro and in vivo evidences demonstrated that deSUMOylation at K26 but not at other sites enhanced the oncogenic activity of YBX1.

Moreover, we confirmed that the carcinogenic effect of YBX1 deSUMOylation at K26 in a DDX5-dependent manner. Consistent with the above results, the proliferation and migration capabilities of Flag-YBX1K26R-overexpressing cells were significantly enhanced compared to those Flag-YBX1-overexpressing cells (Supplementary Fig. S5A–E in the Supporting Information). Conversely, under conditions of DDX5 knockdown, there was no significant difference in proliferation and migration capabilities between Flag-YBX1-expressing cells and those Flag-YBX1K26R-expressing cells (Supplementary Fig. S5A–E in the Supporting Information).

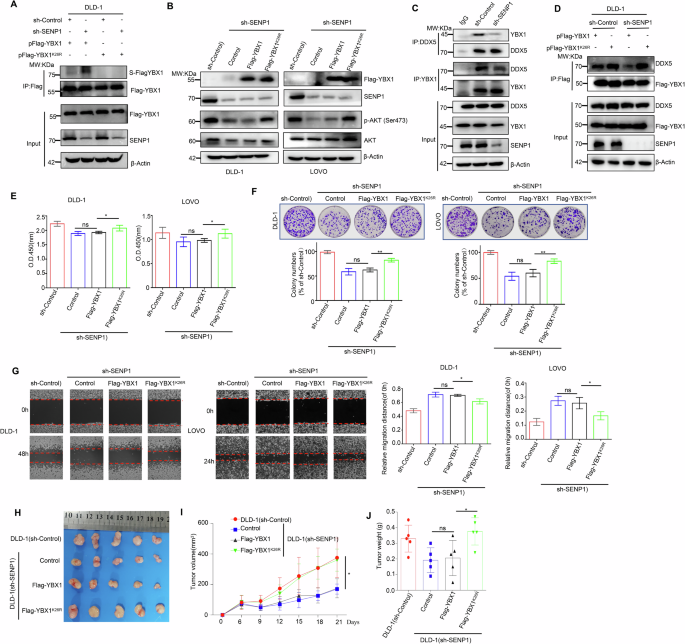

SENP1 facilitates CRC progression partly by catalyzing deSUMOyaltion of YBX1 protein at K26 site

As SENP1 specifically deSUMOylated YBX1, and SUMOylation negatively regulated the oncogenic function of YBX1, we investigated whether SENP1 facilitated CRC progression via inducing deSUMOylation of YBX1 protein. We firstly explored the regulatory functions of SENP1 in CRC cancer cells. SENP1 knockdown significantly down-regulated p-AKT and inhibited CRC cell proliferation, colony formation, and migration, which could be reversed by the overexpression of Flag-tagging SENP1 (Flag-SENP1), but not the Flag-SENP1C603A (Fig. 5A–H, Supporting Information). Together, our data indicated that SENP1 exerted an oncogenic potency mainly dependent on its deSUMO-specific protease role in CRC.

A SENP1 could specifically remove SUMOylation modification at the K26 site of the YBX1 protein. And IP assays indicated the SUMOylation level of Flag-YBX1 in HEK293T cells transfected with indicated plasmids. B Flag-YBX1 or Flag-YBX1K26R overexpression had influence on p-AKT level in CRC cells stably transfecting with sh-SENP1. C SENP1 knockdown had influence on the interaction between cellular endogenous DDX5 and YBX1 in CRC cells. D SENP1 knockdown had influence on the interaction between DDX5 and Flag-YBX1 or Flag-YBX1K26R in CRC cells. E Cell proliferation capacity was compared in Flag-YBX1-expressing or Flag-YBX1K26R-expressing CRC cells under the endogenous SENP1 knockdown. All data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. F Cell proliferation capacity was compared in Flag-YBX1-expressing or Flag-YBX1K26R-expressing CRC cells under the endogenous SENP1 knockdown. Representative images of the colony formation of the indicated cells in top and quantification of clone numbers in bottom. All data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. G Cell migration capacity was compared in Flag-YBX1-expressing or Flag-YBX1K26R-expressing CRC cells under the endogenous SENP1 knockdown. Representative images of the wound healing of the indicated cells in left and quantification of clone numbers in right. All data are presented as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. Scale bar: 100 μm. H–J The subcutaneous tumor capacity was compared in Flag-YBX1-expressing or Flag-YBX1K26R-expressing CRC cells under the endogenous SENP1 knockdown. Tumor images (H), volume (I), and weight (J) were shown. Data were presented as the mean ± SD (n = 5 mice). ns no statistical significance, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. S-Flag-YBX1 SUMOylated Flag-tagging YBX1, S-YBX1 SUMOylated YBX1, IP immunoprecipitation, Input Same account of cell lysate to load, sh-Control short hairpin RNA targeting to empty vector, sh-SENP1 short hairpin RNA targeting to SENP1, Control Flag-vector.

Moreover, we separately transfected the plasmids pFlag-YBX1 and pFlag-YBX1K26R into SENP1-knockdown DLD-1 cells to further investigate whether SENP1 can specifically remove the SUMOylation modification of YBX1 protein at K26. As a result, the knockdown of SENP1 significantly increased the SUMOylation level of the Flag-YBX1 protein (Fig. 5A, lane 1 vs lane 2), yet it failed to induce SUMOylation alteration in Flag-YBX1K26R protein (Fig. 5A, lane 3 vs lane 4), despite the mutant YBX1K26R protein maintained other SUMOylation sites. This observation suggested that SENP1 specifically removed the SUMOylation modification of YBX1 protein at the key K26 site.

Subsequently, we stably transfected pFlag-vector, pFlag-YBX1 and pFlag-YBX1K26R plasmids into SENP1-knockdown cells, respectively. Firstly we detected the p-AKT expression level in each group and the results showed that SENP1 knockdown significantly reduced p-AKT level, while overexpression of the Flag-YBX1K26R protein, but not the Flag-YBX1 protein, restored the expression of p-AKT (Fig. 5B, Lane 3 VS Lane 4), which suggested that SENP1 activated AKT signaling pathway by mediating deSUMOylation of YBX1 protein. Furthermore, we also compared the interaction between YBX1 and DDX5 in CRC cells with stable knockdown of SENP1, and the results showed that SENP1-mediated deSUMOylation of YBX1 indeed promoted the association of these two proteins (Fig. 5C). In addition, to further confirm that SENP1 promoted the binding of YBX1 to DDX5 by specifically removing the SUMOylation of YBX1 at K26 site, we examined the binding of Flag-YBX1 or Flag-YBX1K26R and DDX5 in CRC cells under stable knockdown of SENP1. And the Co-IP assay results showed that knockdown of SENP1 significantly inhibited the binding of Flag-YBX1 to DDX5 protein (Fig. 5D, Lane 1 VS Lane 3), but it did not affect the binding of Flag-YBX1K26R to DDX5 protein (Fig. 5D, Lane 2 VS Lane 4). Besides, the overexpression of Flag-YBX1K26R, but not Flag-YBX1, could alleviate the inhibitory effect of SENP1 knockdown on the proliferation, colony formation and migration of CRC cells (Fig. 5E–G). Taken together, our results suggested that SENP1 mediated YBX1 deSUMOylation at K26 to promote the binding of YBX1 with DDX5, thereby activating AKT signaling pathway and exerting its cancer-promoting ability.

To further determine the function of SENP1 was exerted through inducing YBX1 deSUMOylation in vivo, a CRC cell lines-injected xenograft mouse model was used to compare the differences in tumorigenicity. 1 ×107 CRC cells for each group were inoculated into the right fank of nude mice. About 6 days after injection, the tumors in each group were obviously palpable with 55 mm3, and subsequently the tumor size was totally monitored for five times from then on. Consistent with the in vitro findings, the overexpression of Flag-YBX1K26R but not Flag-YBX1, reversed the inhibitory function of SENP1 knockdown on cellular tumorigenicity in vivo (Fig. 5H–J). At 21 days of inoculation, the tumor volume and weight of SENP1- knockdown xenograft tumors (169.7 ± 43.3 mm3 and 0.20 ± 0.11 g) was the smallest and lightest. However, under SENP1- knockdown xenograft tumors, the overexpression of Flag-YBX1K26R (359.7 ± 94.7 mm3 and 0.38 ± 0.12 g) but not Flag-YBX1 (164.4 ± 82.2 mm3 and 0.21 ± 0.15 g), restored its volume and weight to levels comparable to those of xenograft tumors without SENP1-knockdown (375.5 ± 177.8 mm3 and 0.33 ± 0.12 g) (Fig. 5I–J). Taken together, our in vitro and in vivo data suggested that SENP1 exerted its oncogenic function in part through deSUMOylation at K26 of YBX1 protein.

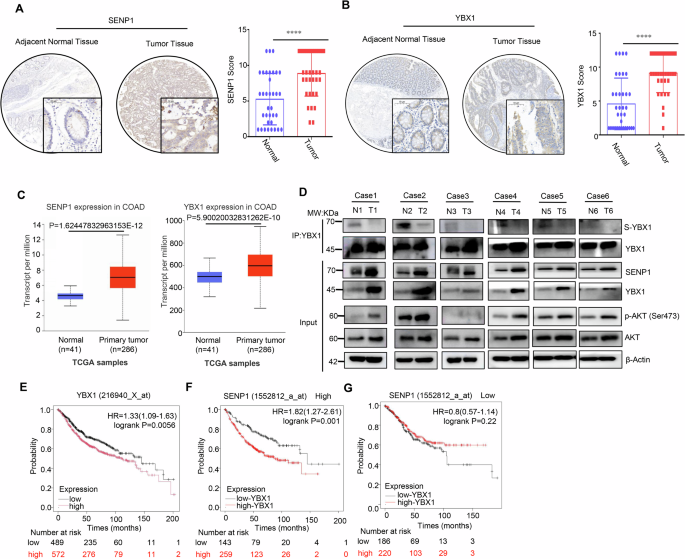

Clinical significance of SENP1-YBX1-AKT signaling axis in human CRC tissues

Finally, we performed IHC staining on commercial tissue microarrays containing 35 paired CRC samples with SENP1 and YBX1 antibodies, and scored every sample on a scale of 0–4 based on the percentage of immunoreactive cells and the staining intensity. The value was obtained by multiplying the positive staining intensity score of each microarray spot with the percentage score of positive staining cells, which was defined as the SENP1 or YBX1 protein expression score. IHC results revealed that SENP1 and YBX1 were both upregulated in CRC tissues compared to the adjacent non-tumor tissues (Fig. 6A, B), consistent with its expression in public database TCGA (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu/index.html) (Fig. 6C).

A Representative images (left) and quantitative analysis (right) of SENP1 expression profiling in CRC tissues and paired normal tissues (n = 25) by IHC staining. Scale bars: 50 μm. Statistical analysis was performed using the paired two-tailed Student’s t test. B Representative images (left) and quantitative analysis (right) of YBX1 expression profiling in CRC tissues and paired normal tissues (n = 25) by IHC staining. Scale bars: 50 μm. Statistical analysis was performed using the paired two-tailed Student’s t test. C Expression variance of SENP1 and YBX1 in CRC tissues and normal tissues of CRC patients using UALCAN portal analysis. D IP and immunoblotting analysis with indicated antibodies in 6 CRC tissues (T) and paired normal tissues (N). Input, whole cell lysates. SUMOyaltion of immunoprecipitated YBX1 was determined and normalized to YBX1 protein (n = 6 samples). E–G Overall survival based on YBX1 expression among all patients or in stratified groups according to SENP1 expression using Kaplan–Meier Plotter portal analysis. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. S-YBX1 SUMOylated YBX1, IP immunoprecipitation, IB immunoblot, Input Same account of cell lysate to load.

To further evaluate the clinical relevance of SENP1-mediated YBX1 deSUMOylation, we performed Co-IP or immunoblotting analysis in 6 paired CRC tissues and para-cancerous tissues. Compared with para-cancerous tissues, SENP1, YBX1 and AKT phosphorylation were significantly upregulated, while YBX1 SUMOylation was obviously downregulated in 6 CRC tissues (Fig. 6D), which indicated that the SUMOylation level of YBX1 displayed a negative relation with the expression level of SENP1 and p-AKT.

In addition, we compared the overall survival duration of CRC patients using the public database Kaplan–Meier Plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis), and found that the association of the high expression of YBX1 with a poor prognosis in CRC patients (Fig. 6E). Interestingly, when patients were stratified by the expression of SENP1, YBX1 lost its role as an indicator for poor outcomes among patients with lower expression of SENP1 (Fig. 6F, G), implicating that high expression of SENP1 might worsen the prognosis of CRC patients by promoting the deSUMOylation of the YBX1 protein. Taken together, these data provide strong evidences that SENP1 induces YBX1 deSUMOylation to promote the activation of AKT signaling and contribute to the poor prognosis of CRC patients.

Discussion

SUMO system plays a pivotal role in regulating diverse cellular processes, such as including cancer cell proliferation, migration, senescence and cancer stem cell maintenance and self-renewal [33,34,35,36,37]. The balance between SUMOylation and deSUMOylation is regulated by SENPs [37]. Among the SENP family, SENP1 stands out as the most well-studied deSUMOylation protease, with its dysregulation involves in tumor progression and associated with the prognosis of patients suffering from various tumor types, including CRC [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. However, the specific role of the SENP1 in CRC is not fully understood before.

Previous reports have demonstrated that the SENP1 exerts pathogenic effects by modulating distinct signaling pathways in various disease contexts, such as NF-κB, STAT3, and AKT pathways [13, 38,39,40]. Our studies have revealed that SENP1 promotes cancer phenotype of CRC cells by specifically activating the AKT signaling pathway, which is largely reported to be regulated by the SUMO pathway. Intriguingly, AKT as a central component of the AKT signaling cascade, is also subject to SUMOylation [36, 37]. And AKT deSUMOtylation significantly decreases itself kinase activity and phosphorylation [41, 42], which suggests activation of the AKT pathway in CRC by SENP1 is unlikely to occur directly via inducing AKT deSUMOylation, implying the presence of alternative regulatory mechanisms of other substrate protein of SENP1. Thus, we postulated that SENP1 presumably governed activation of AKT signaling pathway through the modulation of deSUMOylation events involving other target proteins.

The challenge in detecting SUMOylated proteins at a proteome scale lies in several factors as follows. (1) Target proteins undergo SUMOylation, which are often low abundance, as are SUMO proteins themselves. (2) High deSUMOylase activity leads to a rapid deconjugation of SUMO from the target substrate, complicating in vitro extraction of SUMOylated proteins. (3) Traditional proteomics methods yield long peptide sequences (19 or 23 amino acids) due to lack of K or R residue at the C-terminus of SUMO, hindering MS recognition and reducing proteome coverage [24, 43]. To overcome the challenges in large-scale analysis of SUMO-modified proteome in mammalian cells, we employed an amino acid site-directed mutagenesis approach targeting the C-terminus of SUMO to improve SUMOylated peptides identification by MS/MS. We constructed a lentiviral overexpression plasmid containing a mutant SUMO1T95Kand a 6xHis tag to enhance protein enrichment and specificity. This SUMO1T95K modification, by replacing threonine (T) at position 95 with K, resulted in a unique peptide feature as enzyme digestion. Upon Lys-C cleavage, only two diglycine peptides would be generated on the SUMO-modified K. Crucially, this alteration kept the SUMOylation pattern, and the short -GG sequence minimized false positive ubiquitination interference.

We further employed an integrative LC-MS/MS identification of SUMOylation-proteomics and SENP1 interactomics to identify novel substrate molecules for SENP1-regulated deSUMOylation activity. By integrating SUMO modified proteomics and SENP1-interacting proteins data in this system, we had identified YBX1 as a high-confidence novel substrate of SENP1. Although others have documented that YBX1 could be SUMOylated, and SUMOylation participates in the regulation of YBX1-mediated mismatch repair deficiency and alkylator tolerance [44], the mechanism responsible for the regulation of YBX1 by SENP1 remains to be fully deciphered. Herein our data have confirmed that SENP1 interacts with YBX1 and catalyzes the deSUMOylation of YBX1, which accepts SUMO molecules at K26, K52, K92, K118 and K137. And we also proved that knockdown of SENP1 and YBX1 significantly inhibited cell growth and migration, which could be rescued by introduction of the SUMOylation-deficient mutant Flag-YBX1K26R.

Recent studies have consistently highlighted the pivotal role of PTMs, including phosphorylation, methylation, O-GlcNAcylation, and acetylation, in augmenting the oncogenic potential of YBX1 [45,46,47,48]. Indeed, our studies have revealed SUMOylation of YBX1 impairs its oncogenic properties in CRC cells. The mutant Flag-YBX1K26R but not Flag-YBX14KR exhibited a more pronounced oncogenic effect compared to the wild type Flag-YBX1 protein. Furthermore, the expression levels of SENP1 and YBX1 were increased in CRC and associated with poor outcomes in patients. Interestingly, the prognostic value of YBX1 was not significant in patients with low expression of SENP1, indicating that SUMOylation statue played an important role in the YBX1-mediated pro-tumor effect. Given that stratification is considered as a promising strategy in fighting CRC for the sake of heterogeneity [49], our findings provide evidences for application of YBX1 inhibition in CRC patients with different expression of SENP1.

SUMOylation, a well-established regulator of protein function, modulates substrate protein activities through localization, stability, and intermolecular interactions [50,51,52,53,54,55]. While our results showed that deSUMOylation of YBX1 did not alter its stability and localization in CRC cells. Moreover, through LC-MS/MS analysis, we identified 168 potential YBX1-binding proteins. After rigorous screening and verification, IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, IGF2BP3, HNRPU, G3BP1, YTHDF3, and DDX5 were confirmed indeed YBX1 partners, but only the interaction with DDX5 protein was responsive to the SUMOylation level of YBX1 protein. Increasing evidences have confirmed the oncogenic role of DDX5 in a variety of human tumors [56, 57]. Recently, DDX5 was demonstrated to affect CRC progression by regulating activation of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway [58, 59]. Our findings revealed that DDX5 knockdown abolished the YBX1K26R-involved AKT activation, and SENP1-mediated deSUMOylation of YBX1 enhanced YBX1 interaction with DDX5, which therefore rendered AKT pathway activation and CRC cell excessive proliferation. Moreover, other researches show DDX5 regulates RNA stability, particularly it boosts m6A levels in TLR2/4 mRNA through its interaction with methyltransferases METTL3 and METTL14 [60], and its role in modulating circRNA stability in collaboration with the m6A reader protein YTHDC1 [61]. As previously reported by other studies, YBX1 is recognized as a dedicated m5C reader protein [62]. Thus, the potential role of the YBX1-DDX5 complex in discerning m5C-modified mRNAs and specifically, how the deSUMOylation of YBX1 by SENP1 mediates this process will be elucidated in the future.

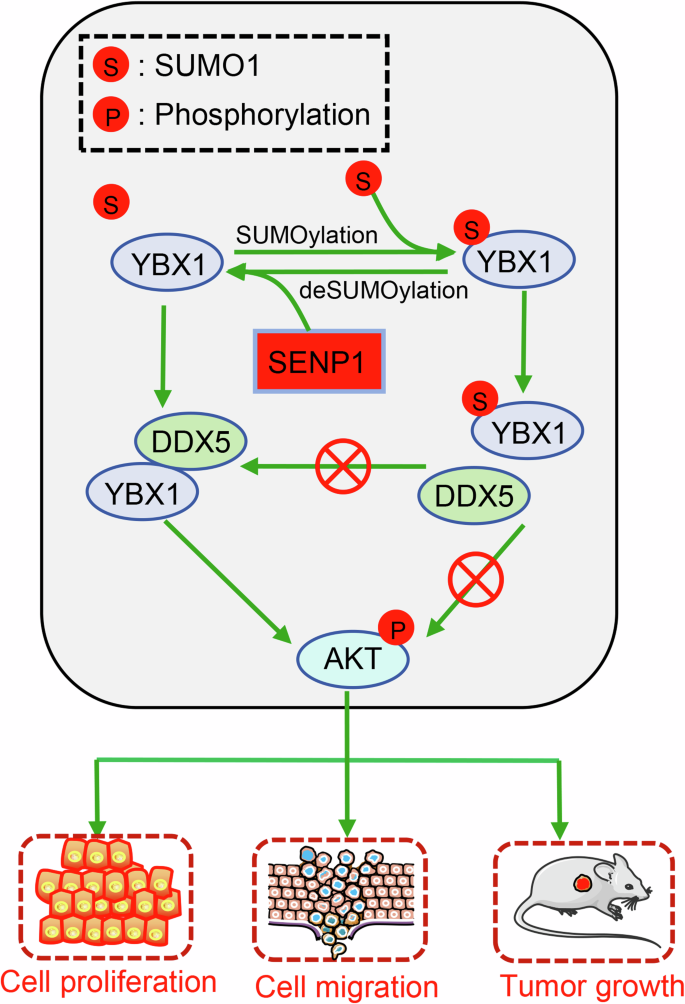

In summary, our findings conclude that knockdown of SENP1 efficiently reduced CRC cell proliferation and migration ability and suppressed activation of AKT signaling, implying a positive role for SENP1 in colon tumorigenesis (Fig. 7). Mechanistically, SENP1 interacts with YBX1 and catalyzes the deSUMOylation of YBX1 at K26, which recruits more DDX5 to activate the AKT pathway, thereby promoting the subsequent progression of CRC. This SENP1-YBX1 interaction is consistent with that the upregulated SENP1 and YBX1 in CRC are related with poor outcomes in patients. Among patients with low expression of SENP1, there has no prognostic difference between patients with different expression level of YBX1. Our study underscores the significance of SENP1-mediated deSUMOylation in CRC progression and suggests targeting the SENP1-YBX1-AKT axis could be a promising therapeutic strategy for CRC.

SENP1 catalyzes deSUMOylation of YBX1 to promote its affixion and recruitment of DDX5 protein, which contributes to cancer cell proliferation and migration.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

The following antibodies were used in this study: β-actin antibody (TA-09, Zsbio), β-tubulin antibody (TA-10, Zsbio), SUMO1 antibody (ET1606-53, Huabio), UBC9 antibody (ET1610-21, Huabio), SENP1 antibody (ET7108-53, Huabio), YBX1 antibody (ET1609-10, Huabio), DDX5 antibody (ET1705-32, Huabio), HNRPU antibody (ET7107-10, Huabio), G3BP1 antibody (HA721314, Huabio), ENOA antibody (ET1705-56, Huabio), FLAG-tag antibody (0912-1 or HA601080, Huabio), Myc-tag antibody (EM31105, Huabio), HA-tag antibody (ET1611-49, Huabio), Lamin B1 antibody (ET1606-27, Huabio), His-tag antibody (66005-1-Ig, Proteintech), IGF2BP1 antibody (22803-1-AP, Proteintech), IGF2BP2 antibody (11601-1-AP, Proteintech), IGF2BP3 antibody (14642-1-AP, Proteintech), YTHDF3 antibody (25537-1-AP, Proteintech), p-AKT (ser473) antibody (381555, ZEN-bioscience), AKT1 antibody (380617, ZEN-bioscience), mouse IgG (A7028, beyotime), rabbit IgG (A7016, beyotime), goat anti-rabbit IgG (HRP) (ZB-2301, Zsbio), goat anti-mouse IgG (HRP) (ZB-2305, Zsbio), and anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 (Ab150113, Abcam).

The following reagents were used in this study: ML-792 (HY-114166), N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) (HY-D0843), and cycloheximide (CHX) (HY-12320), were obtained from Med Chem Express. Anti-Flag Nanobody Magarose Beads (KTSM1355), was ordered from AlpaLifeBio company. BeyoMag™ Protein A+G Beads (P2108) and BeyoMag™ Anti-His Magnetic Beads (P2135) were purchased from Beyotime Biotechnology.

Cell culture

HEK293T, DLD-1 and LOVO cell lines were endowed by Prof. Canhua Huang (State Key Laboratory of Biotherapy, Sichuan University, China) [63] and maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 unit’s penicillin-streptomycin in incubators at 37 °C under 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Plasmid construction and generation of stable cell pools

The cDNA encoding full-length human YBX1 (GI:1519244821) or SENP1 (GI:1519316223) was cloned into pcDNA3.1 or pLVX-EF1α-IRES-EGFP-Puro containing a 3×Flag tag, and the recombinant plasmid named pFlag-YBX1 or pFlag-SENP1 was verified by DNA sequencing. The point mutations of YBX1 (K26R, K52R, K53R, K58R, K64R, K81R, K92R, K93R, K118R, K137R, K170R, K264R, K296R, K301R and K304R), four point mutations of YBX1 (4KR, K52/58/118/137R) and five point mutations of YBX1 (5KR, K26/52/58/118/137R) were constructed by by Beijing Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd., which was confrmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmids pHis-SUMO1, pMyc-SUMO1, and pHA-UBC9 were used and stored in our laboratory [23, 64].

To generate SENP1 or YBX1 stable knockdown (KD) cell pools, shRNA sequence targeting SENP1 (targeting CDS, 5’-CCGAAAGACCTCAAGTGGATT-3’) or YBX1 (targeting 3′UTR, 5’-GCTTACCATCTCTACCATCAT-3’) were cloned into pLKO.1-NEO vector. The retrovirus was produced by using a two-plasmid packaging system according to the previous report [23]. Cells were infected with the retrovirus and selected with G418 (1 mg/mL) for 2 week. pLVX-EF1α-IRES-EGFP-Puro vector was used to rescue SENP1 (WT or C603A) expression in SENP1 KD cells, or YBX1 (WT, K26R or 4KR) expression in YBX1 KD cells. The retrovirus was produced using a two-plasmid packaging system and transfected in SENP1 knockdownt or YBX1 knockdown cells. Cells were then selected with puroromycin (1 μg/ mL) for 1 week.

The CCK8 assay

The CCK8 assay was used to detect the tumor cell viability, and the details were previously described [23, 64, 65]. Briefly, cells (2 ×103 cells per well) were seeded into a 96-well plate to incubate for up to 120 h with medium replenished every 48 h. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm wavelength with a multiwell spectrophotometer.

Colony formation assay

The tumor cell proliferation was analyzed by colony formation assay according to our previous methods [23, 64, 65]. Cells (500 cells per well) were seeded in 6-well plates, and culture medium was changed every 3 days. The colonies were stained with crystal violet staining solution (C0121, Beyotime Biotechnology) for 2 h after 2 weeks.

Wound healing assay

The wound healing assay assay was used to detect the tumor cell migration ability, as previously described [23, 64]. Cells with an appropriate concentration were seeded in 6-well plates. Once the cells were fully adherent, a scratch was made across the center of each well. And Cells were washed with PBS three times to remove the detached cells. After cells were allowed to grow for 24 h in DMEM, wound margins were photographed and cell migration was observed under an inverted microscope [60, 63].

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitation assays

The immunoprecipitation (IP) and co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments were conducted in a standardized manner [23]. For exogenous IP, HEK293T cells transfected with target plasmids were lysed using RIPA buffer, and the supernatant (containing 1-2 mg protein) was incubated with anti-FLAG-agarose or Ni-NTA beads overnight at 4 °C. For endogenous IP, cells or human tissue samples were lysed in RIPA buffer, and after clarification, the supernatants were incubated with anti-SENP1 or anti-YBX1 antibodies for 2 h at 4 °C, followed by protein A/G-agarose binding overnight. Negative controls were established by using normal rabbit IgG for IP to exclude non-specific protein interactions. The precipitates were washed four times with RIPA buffer and analyzed via Western blotting using specific antibodies, such as anti-Flag, anti-SUMO1, anti-SENP1, anti-YBX1, and anti-β-actin. In Co-IP experiments, NP40 lysis buffer replaced RIPA, while all other conditions remained unchanged.

Protein extracts from IP or Co-IP experiments were analyzed using a 7.5–12.5% SDS-PAGE gel to evaluate protein expression levels. Western blot analysis was performed with a panel of specific primary antibodies, including anti-Flag, anti-SUMO1, anti-SENP1, anti-YBX1, and anti-β-actin, to detect the targeted proteins. Following primary antibody incubation, the respective secondary antibodies were bound to the PVDF membrane for detection.

Enrichment of the SUMOylated protein

To test the SUMOylation statues of a target protein, HEK293 T cells were cultured in 10 cm plates and transfected with indicated plasmids. Whole-cell lysates were collected by lysing in SUMO lysis buffer (RIPA buffer + 20 μM NEM + PMSF), subsequent procedures were same as the immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation assays.

SUMOylation identification by mass spectrometry (MS)

HEK293T cells were transfected with pHis-SUMO1T95K for 48 h, SUMO1-tagged proteins were enriched through IP. Proteins were digested with Lys-C alone for 18 h at 37 °C [23], and peptides were identified by Nano LC-MS/MS on an LTQ-Orbitrap (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA). MS data were analyzed by software MaxQuant 1.6.0.1 and Andromeda 1.5.6.0. The search parameters included the human Swiss-Prot database (version 2023.12), allowing up to two missed cleavages for Lys-C, a 7 ppm peptide mass tolerance, and a 0.5-Da fragment mass tolerance for collision-induced dissociation (CID). Fixed modifications included carbamidomethylation, while variable modifications encompassed oxidation, N-terminal acetylation, and KGG (indicative of SUMOylation) [23]. A Mascot confidence level of 95% was enforced, with a minimum requirement of one unique peptide per protein for validation.

SENP1 or YBX1 interacting proteins analysis

For investigating SENP1 or YBX1 interacting proteins, HEK293T cells were transfected with pFlag-SENP1 or pFlag-YBX1 plasmids to enrich Flag-tagging proteins by Co-IP. The immunoprecipitated proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE and stained for 20 min with Coomassie brilliant blue G-250. The protein bands of interest were excised, carefully washed, alkylated, reduced and digested with MS-grade trypsin for 18 h at 37 °C, peptides were identified by MS/MS as described above.

Subcutaneous mouse xenograft model

The animal experimentation protocol was rigorously operated under the ethical approval from the Institutional Animal Care and Treatment Committee of Sichuan University. Aged 4-6 weeks, a balanced cohort of female BALB/c nude mice were procured from Beijing Huafukang Technology Co., Ltd., and randomly assigned for subsequent procedures. To establish a subcutaneous colorectal cancer xenograft model, a suspension of 1 × 107 or 0.5 × 107 DLD-1 cells in 100 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was injected into the right flank of mice, following established methodology [23, 64, 65]. At the 27th day of post-inoculation, mice were humanely sacrificed, and tumors were harvested, documented, weighed, and collected for further analysis. Tumor volumes were measured daily in a blinded manner, employing the formula: tumor volume (mm³) = (length × width²)/2.

Immunohistochemical staining

The CRC tissue microarray was composed of 25 CRC tissues and paired adjacent normal tissues, which was ordered from Wuhan Saiweier Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining and evaluation was carried out as we previously described [23, 66]. Briefly, SENP1 and YBX1 expression levels in CRC samples were detected using IHC with a DAB kit. Semi-quantitative immunoreactive score (IRS) was used to estimate the ratio of SENP1 and YBX1 positive tumor cells. And the primary antibodies for SENP1 and YBX1 were diluted at a ratio of 1:200 for accurate IHC assessment.

Bioinformatics software

UALCAN (http://ualcan.path.uab. edu/analysis-prot.html) databases were used to analyze the difference of SENP1 or YBX1 expression between CRC and normal kidney tissues. Kaplan–Meier Plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) database was used to assess the correlation between SENP1 or YBX1 expression and overall survival in CRC patients.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of Sichuan University and approved by the Animal Care Committee of Sichuan University (Approval number: 20220531054). The CRC samples were collected from General Hospital of Western Theater Command, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of Western Theater General Hospital (Approval number: 2024EC3-ky004). And informed consent was obtained from all participants. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Statistics analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), derived from at least three independent experiments. Survival outcomes were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method. Statistical significance was determined through a two-tailed Student’s t test, with *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

Responses