Sensitivity of rodents to SARS-CoV-2: Gerbils are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, but guinea pigs are not

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which belongs to the Coronaviridae family, causes coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in humans; however, its pathogenicity varies depending on the animal species infected. A number of animal species have been reported to be susceptible to SARS-CoV-21. For example, cats (Felis silvestris catus)2,3, dogs (Canis lupus familiaris)4, mink (Neovison vison)5, white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus)6, Rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta)7, Roborovski hamsters (Phodopus roborovskii)8, and Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus)9 are all susceptible to SARS-CoV-2. In fact, Syrian hamsters are widely used as an animal model of COVID-199,10,11. In contrast, although common marmosets (Callithrix jacchus)7,12 and mice13,14 are frequently used for infectious disease research, they are not readily infected by the ancestral strains of SARS-CoV-2 because of differences in their angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors compared to human ACE2 (hACE2). Although standard laboratory mice are not susceptible to ancestral SARS-CoV-2, hACE2-expressing mice are15. Regarding other rodents, information on their susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 is limited, although one study reported that no SARS-CoV-2 infection was detected in a pet guinea pig housed with a COVID-19 patient16. Guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) are not only popular pets, but also widely used as animal models. There have been reports that guinea pigs can be infected with SARS-CoV17, but no data are available for SARS-CoV-2. Although the SARS-CoV-2 S protein can bind guinea pig ACE2, the mode of binding is different from that of hACE218. Gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus) is also a common pet that is used as an animal model; however, the susceptibility of gerbils to SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 is not known. It is important to know the susceptibility of rodents to SARS-CoV-2 to assess their potential to transmit from humans in the home, as well as in pet breeding and selling facilities. In this study, we examined the sensitivity of guinea pigs and gerbils to SARS-CoV-2 isolated from humans.

Results

Infection of guinea pigs with the D614G, Delta, or Omicron variant

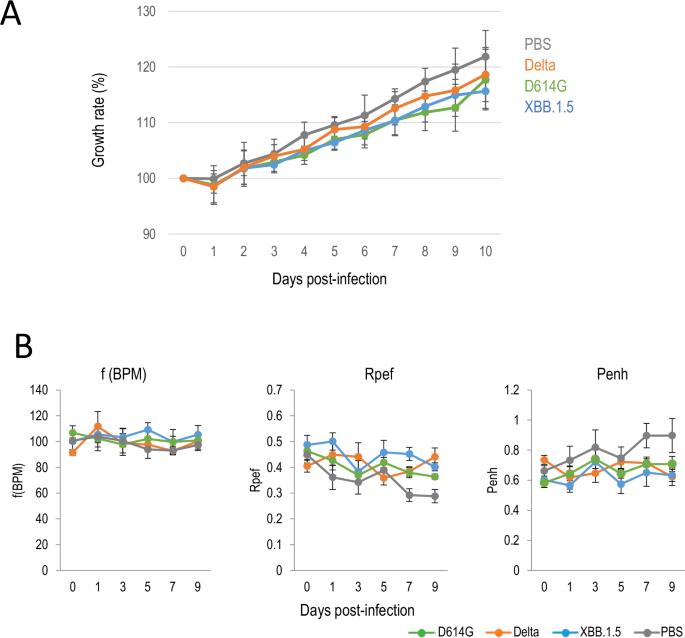

Six-week-old female guinea pigs (n = 4) were anesthetized and intranasally inoculated with 105 plaque forming units (PFU)/animal (in 100 μl) of a D614G variant [SARS-CoV-2/UT-HP095-1N/Human/2020/Tokyo (HP095)] or a Delta variant [hCoV-19/USA/WI-UW-5250/2021 (UW5250)], or an Omicron/XBB.1.5 variant [hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP40900-PIDYSWHNUB/2022 (HP40900)]. Clinical signs and body weight were monitored for 10 days post-infection (dpi). None of the D614G (HP095)-, Delta (UW5250)- or XBB.1.5 (HP40900)-infected animals showed any clinical signs, and their body weights increased similarly and were not significantly different from mock-infected animals (Fig. 1A). We also measured pulmonary function in the infected guinea pigs by measuring f(BPM), Rpef, and Penh, which are surrogate markers for respiratory rate, bronchoconstriction, and airway obstruction, respectively, by using a whole-body plethysmography system. No changes and no significant differences were observed in the f(BPM), Penh, or Rpef of the D614G (HP095)-, Delta (UW5250)- or XBB.1.5 (HP40900)-infected groups compared with the mock-infected group at any time point after infection (Fig. 1B). In addition, no virus was detected in the nasal turbinates or lungs of any of the D614G (HP095)-, Delta (UW5250)- or XBB.1.5 (HP40900)-infected animals at 3 and 6 dpi (data not shown). None of the animals had antibodies to SARS-CoV-2, as determined by using blood collected at 21 dpi in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent (ELISA) assay (data not shown). These results indicate that guinea pigs are not susceptible to the D614G (HP095), Delta (W5250), or XBB.1.5 (HP40900) variants.

A, B Guinea pigs were intranasally inoculated with 105 PFU of D614G (HP095), Delta (UW5250), or XBB.1.5 (HP40900), or with PBS (mock). A Growth rate of infected guinea pigs. The growth rate of virus-infected (n = 4) and mock-infected (n = 4) guinea pigs was monitored by recording their body weight daily for 10 dpi. Body weights of individual animals are shown as the percentage of the body weight compared with that on Day 0. B Pulmonary function of infected guinea pigs. For pulmonary function analyses in virus-infected (n = 5) and mock-infected (n = 4) guinea pigs, f(BPM), Rpef and Penh, were measured by using whole-body plethysmography. Data are means ± s.e.m.

Infection of gerbils with the ancestral strain, Delta, or Omicron variant

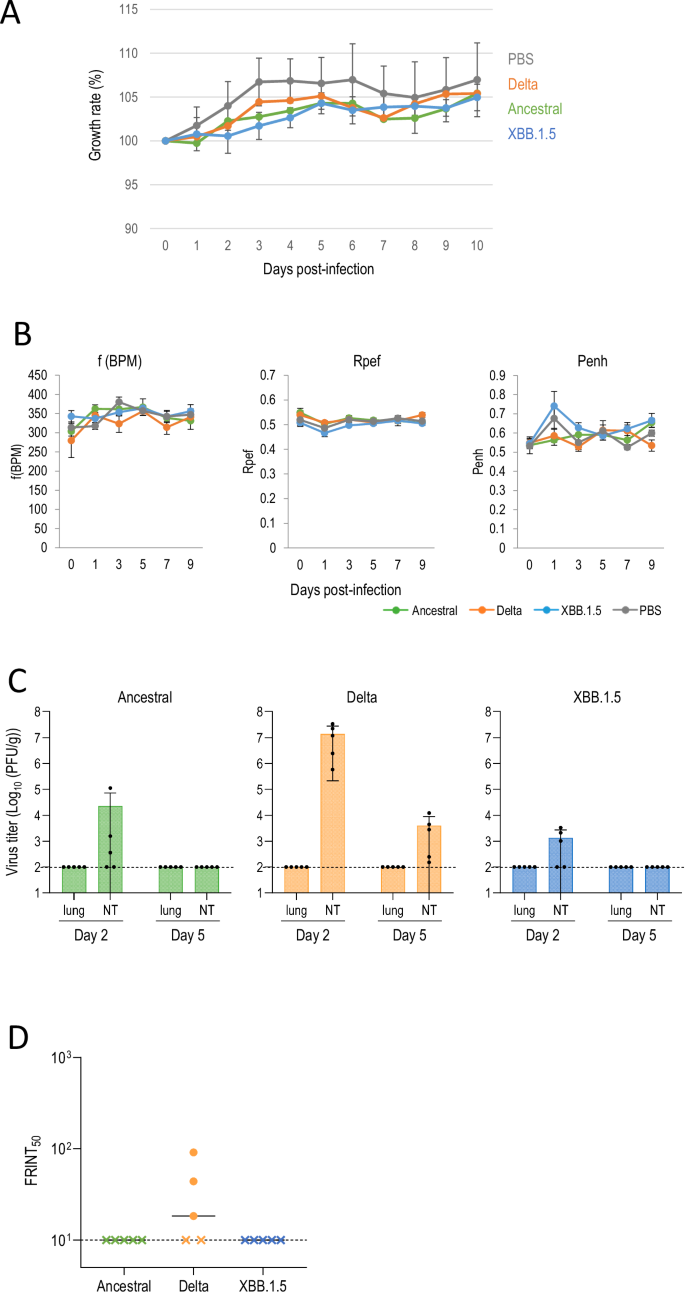

Six- or seven-week-old female gerbils (n = 5) were anesthetized and intranasally inoculated with 105 PFU/animal (in 50 μl) of the ancestral strain [SARS-CoV-2/UT-NC002-1T/Human/2020/Tokyo (NC002)], Delta (UW5250), or XBB.1.5 (HP40900). Clinical signs and body weight were monitored for 10 dpi. None of the animals infected with ancestral (NC002), Delta (UW5250), or XBB.1.5 (HP40900) showed any clinical signs, and their body weights increased similarly and were not significantly different from mock-infected animals (Fig. 2A). No changes and no significant differences were observed in the f(BPM), Penh, or Rpef of the ancestral (NC002)-, Delta (UW5250)-, or XBB.1.5 (HP40900)-infected groups compared with the mock-infected group at any time point after infection (Fig. 2B). Although no virus was detected in the lungs of any of the animals, the ancestral (NC002), Delta (UW5250), and XBB.1.5 (HP40900) viruses were recovered from the nasal turbinates of the infected gerbils (Fig. 2C). The ancestral (NC002) and XBB.1.5 (HP40900) viruses were recovered from 3 of 5 gerbils at 2 dpi but not at 5 dpi. In contrast, Delta (UW5250) replicated in the nasal turbinates of all gerbils at 2 and 5 dpi. To detect antibody responses to infection, we performed a focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT). Although the virus was isolated from the nose of animals infected with the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 or XBB.1.5 variant, neutralizing antibodies were not detected (Fig. 2D). However, three of five gerbils infected with Delta variant had neutralizing antibodies (Fig. 2D).

A–D gerbils were intranasally inoculated with 105 PFU of ancestral (NC002), Delta (UW5250), or XBB.1.5 (HP40900), or with PBS (mock). A Growth rate of infected gerbils. The growth rate of virus-infected (n = 5) and mock-infected (n = 5) gerbils was monitored by recording their body weight daily for 10 dpi. Body weights of individual animals are depicted as the percentage of the body weight compared with that on Day 0. B Pulmonary function of infected gerbils. For pulmonary function analyses in virus-infected (n = 5) and mock-infected (n = 5) gerbils, f(BPM), Rpef and Penh were measured by use of whole-body plethysmography. Data are means ± s.e.m. C Virus replication in infected gerbils. Gerbils were euthanized at 2 and 5 dpi for virus titration. Virus titers in the nasal turbinates (NT) and lungs were determined by performing plaque assays. Data are means ± s.e.m.; points represent data from individual animals. The detection limit is indicated by the horizontal dashed line. D Neutralizing antibody titers of serum obtained from each animal at 21 dpi. FRNT50 values were determined in Vero E6-TMPRSS2-T2A-ACE2 cells. Each dot represents a value from one animal. The lower limit of detection (value = 10) is indicated by the horizontal dashed line. Samples under the detection limit (<10-fold dilution) were assigned an FRNT50 of 10 and are represented by X.

Discussion

Here, we showed that gerbils are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, but guinea pigs are not. For the experimental infection of guinea pigs, we used three SARS-CoV-2 variants: the early variant D614G, a Delta variant, and the more recent variant Omicron/XBB.1.5. D614G replicates efficiently in hamsters19. The Delta variant is highly pathogenic in hamsters20 and hACE2 transgenic mice21, whereas Omicron variants are less pathogenic than D614G in hamsters22 and in hACE2 transgenic mice21,23. Our study thus demonstrates that three variants with different pathogenicity do not replicate in guinea pigs. Moreover, we did not detect antibodies to these viruses in any of the guinea pigs, indicating that these variants did not replicate in the guinea pigs at all. Brooke and Prischi analyzed the ACE2 of various animal models by using structural and functional modeling, and found that although the SARS-CoV-2 S protein can bind guinea pig ACE2, the mode of binding differs from that to hACE218. These data are consistent with our finding that guinea pigs lack susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2.

Regarding gerbils, there have been no previous reports on their sensitivity to SARS-CoV-2 or the character of their ACE2. We analyzed the sensitivity of gerbils to three SARS-CoV-2 variants: the ancestral strain; a highly pathogenic Delta variant, and a less pathogenic Omicron/XBB.1.5 variant, as described above. Although the virus replicated in the nasal turbinates but not the lungs of gerbils, the pathogenicity trend was consistent with that seen in hamsters and hACE2 transgenic mice in that Delta showed the highest pathogenicity, followed by the ancestral virus, and then Omicron. In addition, neutralizing antibodies were produced in gerbils infected with the Delta variant. Further research comparing the ACE2 of guinea pigs and gerbils would be valuable for understanding differential susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 among rodents. It is well known that hamsters are highly susceptible to SARS-CoV-29,10,11. In this study, gerbils were also found to be susceptible to SARS-CoV-2, although less susceptible than hamsters. Given that pet sellers often displayed rodents in the same area, caution should be exercised during COVID-19 outbreaks.

Materials and methods

Cells

VeroE6/TMPRSS224 (JCRB 1819) cells were propagated in growth medium in the presence of 1 mg/ml geneticin (G418; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) and 5 μg/ml plasmocin prophylactic (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) containing 10% FCS and antibiotics. VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2, and regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination by using PCR and were confirmed to be mycoplasma-free.

Viruses

Ancestral strain, SARS-CoV-2/UT-NC002-1T/Human/2020/Tokyo (NC002); D614G variant, SARS-CoV-2/UT-HP095-1N/Human/2020/Tokyo (HP095); Delta variant, hCoV-19/USA/WI-UW-5250/2021 (UW5250); and Omicron/XBB.1.5 variant, hCoV-19/USA/MD-HP40900-PIDYSWHNUB/2022 (HP40900) were propagated in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells in VP-SFM (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.).

All experiments with SARS-CoV-2 were performed in enhanced biosafety level 3 (BSL3) containment laboratories at the University of Tokyo, which are approved for such use by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, and Fisheries, Japan.

Animals

Five-week-old female Hartley guinea pigs and five- or six-week-old female Mongolian gerbils were purchased from Japan SLC Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan). After about one week of acclimation, the then six-week-old guinea pigs and six- or seven-week-old gerbils were used for this study. The animal room was kept at 25 °C and 50% humidity. Food and tap water were supplied ad libitum.

Experimental infection of guinea pigs

Under atropine and ketamine-xylazine anesthesia, 12 guinea pigs per group were intranasally inoculated with 105 plaque forming unit (PFU)/animal of D614G (HP095), Delta (UW5250), or XBB.1.5 (HP40900) virus in 100 μl. To assess virus growth in respiratory organs, animals were euthanized at 3 and 6 dpi (n = 4 per time point) and nasal turbinates and lungs were collected. The collected organs were homogenized with MEM containing 0.3% BSA and titrated in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells by using plaque assays. The remaining animals (n = 4) were monitored daily for body weight changes for 14 dpi. Respiratory parameters [f(BPM), respiratory rate; Penh, a nonspecific assessment of breathing patterns; and Rpef, a measure of airway obstruction] were also measured on days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 by using a whole-body plethysmography system (Prime Bioscience Pte Ltd, Pantech Business Hub, Singapore) as previously described25,26. Baseline body weight and respiratory parameters were measured prior to infection. These animals were euthanized at 21 dpi and sera were collected for antibody titer measurements.

Experimental infection of gerbils

Under isoflurane anesthesia, 15 gerbils per group were intranasally inoculated with 105 PFU/animal of ancestral (NC002), Delta (UW5250), or XBB.1.5 (HP40900) virus in 50 μl. To assess virus growth in multiple organs, animals were euthanized at 2 and 5 dpi (n = 5 per time point) and brain, olfactory bulb, liver, spleen, kidney, jejunum, colon, heart, lung, and nasal turbinate were collected. The collected organs were homogenized with MEM containing 0.3% BSA and titrated in VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells by using plaque assays. The remaining animals (n = 5) were monitored daily for body weight changes for 14 dpi. Respiratory parameters (Penh and Rpef) were also measured on days 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 by using a whole-body plethysmography system (Prime Bioscience). Baseline body weight and respiratory parameters were measured prior to infection. These animals were euthanized at 21 dpi and sera were collected for antibody titer measurements.

Plaque assay

Viruses were diluted in the growth medium. Confluent monolayers of VeroE6/TMPRSS2 cells were infected with the diluted viruses, and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. After the virus inoculum was removed, the cells were washed with growth medium and overlayed with a 1:1 mixture of 2x growth medium and 2% agarose. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 48 h before virus plaques were counted.

ELISA

Ninety-six-well Maxisorp microplates (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) were incubated with 2 μg/ml of recombinant RBD (ancestral strain-type) or ectodomain (ancestral strain-type, Delta, BA.1, and BA.2) of the S protein, the N protein (ancestral strain-type) or with PBS at 4 °C overnight and were then incubated with 5% skim milk in PBS containing 0.05% tween-20 (PBS-T) for 1 h at room temperature. Serum samples were diluted 40-fold in PBS-T containing 5% skim milk. As positive controls, human monoclonal antibodies (S309, Ly-CoV1404, and S2P6) and a mouse anti-His mAb were used. The microplates were reacted for 1 h at room temperature with the diluted serum samples, followed by peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig IgG (H + L) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. West Grove, PA, USA), peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG Fcγ Fragment specific antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.), or peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG, Fcγ Fragment specific antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.). After the plates were washed, 1-Step Ultra TMB-Blotting Solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) was added to each well and incubated for 3 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped by the addition of 2 M H2SO4 and the optical density at 450 nm (OD450) was immediately measured. A OD450 value of 0.1 or more was regarded as positive.

Focus reduction neutralization test (FRNT)

Neutralization activities of serum were determined by using a focus reduction neutralization test as previously described27. Briefly, the samples were first incubated at 56 °C for 1 h. Then, the treated serum samples were serially diluted five-fold with DMEM containing 2% FCS in 96-well plates and mixed with 100–400 FFU of virus/well, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 1 h. Fifty microliters of the serum-virus mixture was inoculated onto Vero E6-TMPRSS2-T2A-ACE2 cells in 96-well plates in duplicate and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Then, 100 μl of 1.5% Methyl Cellulose 400 (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) in culture medium was added to each well. The cells were incubated for 14–16 h at 37 °C and then fixed with formalin.

After the formalin was removed, the cells were immunostained with a rabbit monoclonal antibody against SARS-CoV-2 nucleoprotein (Sino Biological Inc., dilution: 1:10,000, Cat #: 40143-R001) followed by a horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., dilution: 1:2000, Cat #: 111-035-003). The infected cells were stained with TrueBlue Substrate (SeraCare Life Sciences) and then washed with distilled water. After cell drying, the focus numbers were quantified by using an ImmunoSpot S6 Analyzer, ImmunoCapture software, and BioSpot software (Cellular Technology). The results are expressed as the 50% focus reduction neutralization titer (FRNT50). The FRNT50 values were calculated by using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software). Samples under the detection limit (<10-fold dilution) were assigned an FRNT50 of 10.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the values measured for each experiment and the mean value. A two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test was performed, and differences were considered to be statistically significant when the p-value was less than 0.05.

Ethics statements

The research protocol for the animal studies is in accordance with the Regulations for Animal Care at the University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan, and was approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of the Institute of Medical Science of the University of Tokyo (approval number: PA21-25, PA21-43). Animals were humanely euthanized by total blood collection or release under deep anesthesia with ketamine-xylazine (for guinea pigs) or isoflurane (for gerbils) to minimize any suffering after virus infection.

Responses