Sewage sludge hydrochar characterization and valorization via hydrothermal processing for 3D printing

Introduction

Sewage sludge, the biosolid product of wastewater processing, is an abundant source of rich organic compounds and nutrients including nitrogen and phosphorus. Each year the US generates 6 million dry metric tons of treated sewage sludge1, and globally this figure is estimated to be around 144 million dry metric tons2. Treated sewage sludge can be used in land applications such as soil amendment or fertilizer. However, presence of microplastics and other pollutants limits land distribution, and over half of the sewage sludge produced in the US is incinerated, sent to landfills, or otherwise disposed of, escalating issues associated with greenhouse gas emissions and solid waste accumulation1. There is a clear need for better solutions to the prevalence of sewage sludge.

In typical wastewater processing, primary sludge is extracted with chemical precipitation and sedimentation, and suspended organic matter is extracted with biological treatment as secondary sludge, after which the sludges are combined for further treatment. At this stage, anaerobic or aerobic digestion is used to stabilize the solids and neutralize harmful pathogens. Sludge is then typically dewatered to concentrate the solid matter, which comes with its own set of challenges3,4, after which it is ready for reuse or disposal5.

Treated sewage sludge has been investigated for use as toxic compound adsorbents6,7,8,9,10, as cement fillers for structural materials11,12,13, and in other applications14,15, both as-is and after further processing. Recent endeavors to further valorize sewage sludge include producing biofuels through anaerobic co-digestion with food waste to produce methane16, conversion into high-lipid black soldier fly larvae for biodiesel production17,18, and crude bio-oil production through hydrothermal processing (HTP), a method that uses high heat and high pressure to convert wet biomass into crude-like bio-oils. HTP in particular is a promising method for valorizing sewage sludge and other biomass wastes because it can be performed on hydrated biomass materials. This bypasses energy-intensive de-watering and drying steps that are required for methods such as pyrolysis, enabling more efficient energy recovery from biomass sources19,20. Furthermore, subcritical or supercritical water is used as a solvent in HTP, avoiding need for more toxic solvents often used in other processing methods21. In addition to biocrude oils, HTP also produces solid residues known as hydrochar and gaseous products (Fig. 1a)22,23,24. The yield and chemical formulation of HTP products depend highly on biomass source and reaction conditions.

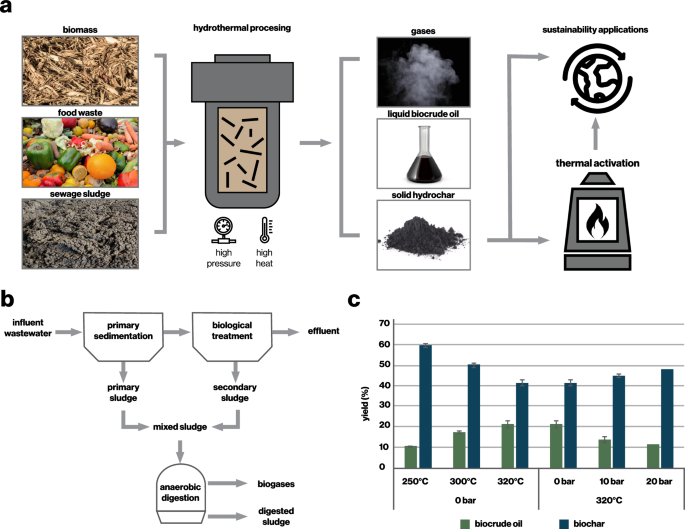

a Hydrothermal processing of hydrated organic wastes under high heat and high pressure produces products in three phases: gases, liquid biocrude oils, and solid hydrochar components. Images attributed to: Roberto Sorin, TheStockCube, digidreamgrafix, mputsylo, Nikolay, and sansiripech for biomass, food waste, sewage sludge, gases, biocrude oils, and solid hydrochar, respectively (stock.adobe.com). b Conventional sewage sludge processing. c Biocrude oil and hydrochar yields under several conditions of reactor pressure and temperature. Error bars denote standard deviation calculated over experiments completed in at least triplicate.

HTP for sewage sludge management has been found to eliminate toxic chemicals and to have an 11-fold higher energy recovery than landfilling sewage sludge25,26. Some studies have further investigated effects of different parameters on sewage sludge HTP yields27,28,29, however most focus on the production of fuels including solids for char combustion30, liquid bio-fuels30,31, or methane-rich biogas32. Even so, sewage sludge-derived hydrochar often has lower higher heating value than even low-grade coals, limiting its use as solid fuels33. In contrast, HTP has demonstrated potential to create more complex value-added materials from biomass such as biocomposite fillers34,35, electrode materials23,36, and advanced carbon-based nanomaterials37,38. Oftentimes, this requires additional processing of the solid hydrochar products through physical (heat) or chemical (catalyzed) activation, which converts the hydrochar into graphene oxide-like nanostructured carbon with high surface area and porosity. These activated carbons (ACs) typically have decreased heteroatom content and increased carbon crystallinity, which can imbue additional properties such as enhanced strength, enhanced adsorption capacity, or conductivity22. This opens up doors to diverse applications including gas adsorption39,40,41, water purification41,42, and energy storage43.

As composite filler materials, hydrochars and ACs from biomass have the potential for two-fold benefit in reducing raw material consumption and lending additional functionality based on the properties of the carbonaceous materials22,23,36,44,45. In particular, functionalized 3D printing composites can improve the efficiency of various industries by enhancing material properties, enabling fabrication of complex architectures such as to increase surface area, and enabling on-demand production22,23,36,44,45. Several hydrochar-based 3D printing composites derived from lignocellulosic sources have already been investigated such as with incorporation into poly(lactic acid), and have been shown to generally improve mechanical properties of the printed materials46,47,48 as shown in Table 1.

Here we investigate the hydrothermal processing of sewage sludge and subsequent physical activation, characterizing the physical and chemical properties of sewage sludge hydrochar and ACs to consider their potential application spaces. We explore the impact of temperature and pressure on bio-oil and hydrochar yield and composition, as well as changes effected by physical activation. We further investigate the printability and mechanical characteristics of hydrochar-resin composites. Especially considered as a byproduct of biofuel production, utilizing hydrochar in 3D-printing reduces consumption of raw synthetic materials and enables more sustainable waste management. Finally, we explore how nature-inspired strategies such as hierarchical material architecting can improve functionality of the composites, even when increasing sustainability comes at a trade-off with mechanical properties.

Results

Hydrothermal liquefaction of sewage sludge

Sewage sludge was subjected to hydrothermal processing under five different conditions that are typical for biomass HTP: 250 °C, 300 °C, and 320 °C at 0 bar, as well as 320 °C at 10 bar and 20 bar49,50. The biocrude oil and hydrochar yield results are shown in Fig. 1c and Table S1. Products of HTP are governed by a balance between various parameters including feedstock, loading, temperature, pressure, and time. Here, as a whole, yield of biocrude oil increased as temperature increased while yield of hydrochar decreased. This is consistent with previous studies that indicated the optimal HTP conditions for biocrude oil production from sewage sludge to be approximately 320 °C or 330 °C31. In similar vein, high temperature ( > 260 C) HTP is often termed hydrothermal liquefaction for its tendency toward high biocrude yield25. Conversely, yield of biocrude oil decreased and yield of biochar increased as pressure increased. High pressure may have been favorable for repolymerization reactions that enhance the formation of hydrochar51. The aqueous and gaseous phases were not captured. High temperature and low pressure (0 bar, 320 °C) resulted in the highest biocrude oil yield, which is desirable for common biofuel and asphalt applications, while low temperature and low pressure (0 bar, 250 °C) resulted in the highest hydrochar yield.

Physical & chemical characterization

The subset of hydrochars produced at 0 bar and 250 °C, 300 °C, and 320 °C, which we will reference as H250, H300, and H320, were selected for further analysis since these lower pressure operating conditions are safer and more energy efficient and offered comparable or higher biocrude and hydrochar yields than their high-pressure counterparts. For further valorization, these hydrochars were subjected to thermal activation to produce AC, a process that typically produces porous carbonaceous materials with enhanced mechanical properties52. We will reference the respective activated carbons as AC250, AC300, and AC320 (Table 2).

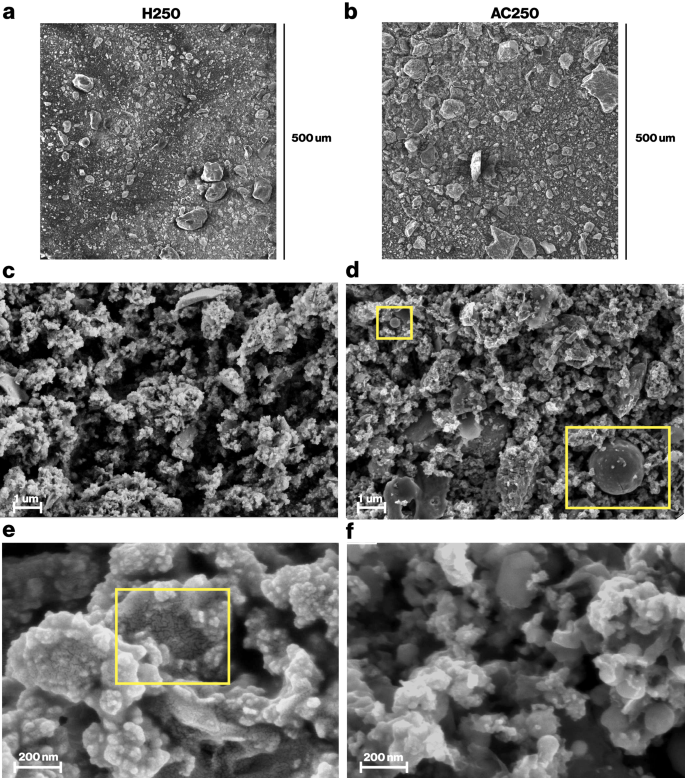

Visually, thermal activation transformed the hydrochars from a dark brown color to a deep black color. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were used to further consider the differences between activated and unactivated samples. SEM micrographs of H250 and AC250 are shown in Fig. 2 as representative samples; micrographs of H300 and H320 and their respective ACs displayed similar trends and can be found in Supplementary Figs. 1–3. Interestingly, powdered ACs appeared to have a higher quantity of large particles ( > 50 µm) than powdered hydrochars even though all samples underwent the same milling process. Upon closer inspection (Fig. 2c, d), the hydrochars and ACs appeared to have similar microstructural topology and coarseness even though activation processes typically create more porous materials with increased carbon content53. At very high magnification, however, some nanostructural differences between hydrochars and ACs were revealed (Fig. 2e, f). In hydrochars, material surfaces were marred by networks of very fine nanoscale cracks on the order of 10 s of nanometers. In ACs, surfaces were relatively smooth and carbon nanospheres could be found, demonstrating evidence of restructuring within the material.

SEM micrographs of sewage sludge biochar directly after hydrothermal processing (a, c, e) and after further thermal activation (b, d, f). Hydrochar appears to have fewer large particles (a) than activated carbon (b). At 10 KX magnification, hydrochar (c) and activated carbon (d) have similar roughness and morphology, aside from the formation of carbon nanospheres (framed in yellow boxes) in activated carbon. At 80 KX, hydrochar exhibits a network of nanoscale cracks (framed in yellow boxes) throughout its surfaces (e) while activated carbon appears to have sharper edges but smoother surfaces (f).

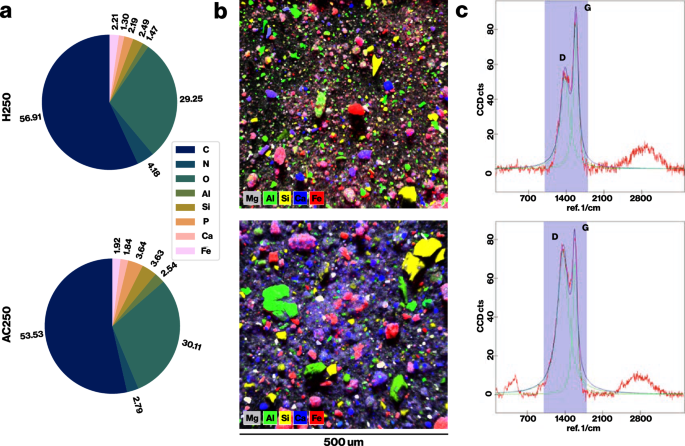

XPS analysis of elemental composition revealed that carbon content of sewage sludge hydrochars increased with increasing HTP temperature as expected54. Interestingly, however, across hydrochars from all HTP conditions, carbon content decreased after thermal activation, the opposite effect of what is typically expected (Fig. 3a, Table 3). This may be attributable to the large presence of metallic and metalloid elements such as silicon and aluminum that are not typically found in biomass residues. Interestingly, one study also found that carbon is preferably transferred to the liquid phase in HTP processing of sewage sludge29. Here, with thermal activation, nitrogen content decreased as expected but all other dopants increased in relative concentration, likely because they could not be pyrolyzed while carbon and nitrogen-based compounds were. Furthermore, energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) scans showed that some dopants including aluminum and silicon were present as small grains rather than dispersed homogenously throughout the material, and these increased in grain size after activation as if annealed, contributing to the larger particles observed in ACs. This is shown for H250 and AC250 in Fig. 3b.

Representative data from H250 and AC250; data from the remaining samples displayed similar trends and can be found in supplementary materials. a Elemental composition of hydrochar and activated carbon from XPS analysis. Relative carbon content decreased after thermal activation, while relative content of metallic and metalloid dopants increased. b Metallic and metalloid dopants were congregated in individual particles rather than dispersed throughout. Particle sizes in hydrochar (top) increased after thermal activation (bottom). Micrographs are of the same scale. c Raman spectra from hydrochar (top) and activated carbon (bottom) are characteristic of disordered carbons, with relatively broad D and G bands (in purple highlight) indicating higher disorder detected in the activated carbon.

Raman spectroscopy was used to assess the aromatic structure of the materials and revealed structural reordering further: spectra of disordered graphitic carbons typically exhibit two bands around 1357 and 1580 cm−1, often referred to as the D and G bands respectively, whose intensity and line width are characteristic of the carbon structure55. In particular, higher D band intensity is indicative of higher disorder including defects and vacancies, while higher G band intensity is representative of in-plane vibrations of aromatic sp2 atoms23. Here, the D/G band intensity ratio was higher among the ACs than the hydrochars, indicating that the material had become more disordered after physical activation (Fig. 3c, Table 4). This suggests that despite some congregating of the inorganic dopants, the increased relative ratio of dopants still had a negative overall effect on graphitic ordering of the carbons. This is further supported by findings that sewage sludge ACs derived through pyrolysis also possessed high heavy metal and silicon content compared to typical commercial ACs, which resulted in unique microstructure and different adsorption behavior56. As before, decreased graphitic ordering is contrary to what is typically expected for activation processes. Amongst the hydrochars, Raman spectra were internally consistent and displayed similar trends, as did the Raman spectra for the ACs. Nevertheless, both hydrochars and ACs displayed two relatively broad peaks characteristic of highly disordered carbons55. Figure 3 shows the elemental composition, EDS scans, and Raman spectra for H250 and AC250 as representative analysis; this data for the remaining samples can be found in Supplementary Figs. 4-5.

The hydrochars were slightly more insulating than the ACs as evidenced by both slight shifting in their XPS spectra and by charge accumulation during SEM imaging. However, measurable conductivity was not detected in any of the samples with resistivity measurements on pressed powders, powders dispersed in deionized water, or in hydrochar and AC-doped composites. Some bio-based activated carbons do demonstrate conductivity22,23, however, conductive ACs typically have much higher carbon content (90+ wt%) than the sewage sludge-derived ACs here (50–60 wt%), which enables higher carbon crystallinity and electron delocalization57.

Incorporation of sewage sludge into 3D printing materials

So far, we have investigated the products of hydrothermal processing of sewage sludge and the effects of an additional thermal activation step. As a potential route for valorization, we next investigated the use of the resulting sewage sludge hydrochars and ACs as sustainable fillers for 3D printing. Briefly, for each sample, powdered hydrochar or AC was mechanically mixed into liquid-crystal display 3D printing resin and sonicated for dispersion, and this mixture was used directly in 3D prints (Fig. 4a). These materials were tested with micro indentation and in tension and compression to determine bulk mechanical properties of the resulting composites.

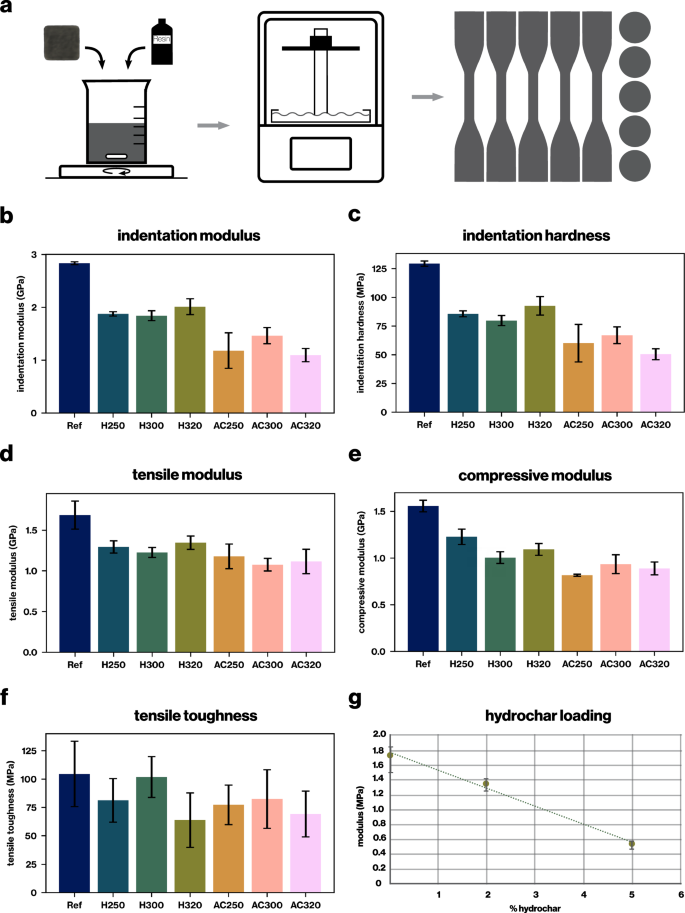

a Hydrochar and commercial resin are combined with mechanical mixing and sonification for dispersal, after which the mixture can be used for 3D-printing with a DLP system. Incorporation of sewage sludge-based residues decreases the indentation modulus (b) and hardness (c) of printed composites. Similar trends are observed with tensile modulus (d), compressive modulus (e), and tensile toughness (f). g Composite modulus scales approximately linearly with respect to hydrochar (H320) loading. In all plots, error bars denote standard deviation calculated over 20–25 measurements (b, c) or over experiments completed in replicates of 5 (d–g).

Microindentation revealed that both indentation hardness and indentation modulus decreased with incorporation of hydrochar, and even more so with incorporation of ACs (Fig. 4b, c). As shown in Fig. 4d-f, tensile modulus, tensile toughness, and compressive modulus all demonstrated similar trends. This is consistent with some findings that incorporation of various hydrochars and ACs into 3D printing materials like poly(lactic acid) resulted in decreased tensile strength47,58, including a study that utilized biochar from pyrolysis of sewage sludge59. In contrast, some studies have found that bio-based carbonaceous filler can increase tensile modulus in composites46,47,58,60,61. This has been proposed to be a result of the higher rigidity of hydrochar and AC fillers relative to 3D printing plastics62, and the high surface area of the biochar which enhances adhesion between matrix and filler materials63,64. In this case, diminishing mechanical properties with the addition of hydrochar and AC suggest limited adhesion between the cured resin and the fillers, which inhibits stress transfer and allows deformability, or poor mechanical properties in the hydrochars and ACs themselves. In similar vein, elongation at break decreased with addition of the hydrochars and ACs, as is often seen in plastics with nonintercalated fillers, which can aggregate and cause embrittlement65. Nevertheless, up to 5 wt.% hydrochar was still easily incorporable and printable (Fig. 4g), demonstrating that notable portions of synthetic 3D-printing resins can be replaced with sewage sludge as a more sustainable filler, especially in applications such as visual prototyping where mechanical strength is not of pinnacle importance. Even higher hydrochar loading is likely feasible as some studies have shown plastic composites with up to 20% biochar loading59, however the mechanical properties of resulting composites are expected to continuously decrease which presents an important tradeoff to consider.

An interesting observation is that the hydrochar-filled composites displayed stronger mechanical properties than the AC-filled composites. One potential explanation for this is the nanoscale cracks previously observed throughout the hydrochars, which may enhance adhesion with resin by increasing surface area and promoting resin impregnation. Another potential explanation is the higher degree of order observed in hydrochars, which may contribute to stronger mechanical properties within the hydrochar powders themselves as compared to the ACs.

Because the mechanical behavior of composites with the various hydrochars were quite similar, H250 was selected as a representative material for the remaining experiments based on the quantity of material available. The hydrochar imbued a rich dark color to printed specimens, as can be seen in Fig. 5a.

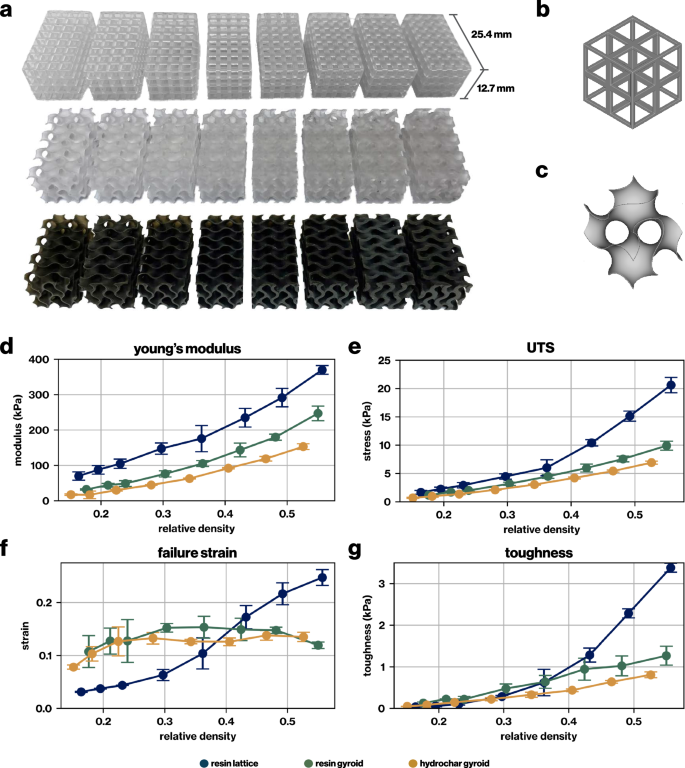

Commercial resin was used to fabricate samples in a range of relative densities with (a) traditional lattice infills and (b) bioinspired gyroid infills. c Alongside the resin prints, hydrochar-loaded resin was used to fabricate samples in a range of relative densities with gyroid infills. These samples were tested in compression to find their (d) effective moduli, (e) fracture strength, (f) strain-at-failure, and (g) toughness. Especially at lower densities, biomass-loaded resin can achieve toughness and elongation that exceeds conventional resin alone by using bio-inspired architecture. In all plots, error bars denote standard deviation calculated over experiments completed in at least triplicate.

Use of gyroid geometries to recover mechanical properties

Many materials in nature are composed of relatively weak building blocks but achieve remarkable properties through careful architecting of their microstructures66,67,68,69. With this inspiration, we investigated the use of geometry to enhance the mechanical properties of the relatively weaker hydrochar composites. A bio-inspired gyroid geometry was employed, which is trigonometrically approximated by Eq. (1).

Gyroids are triply periodic minimal surfaces that have been observed in butterfly wing scales, bird feathers, and mitochondrial membranes70,71. As a lattice structure, gyroids have been shown to yield high tensile strength materials with low density as well as near isotropy, and have been investigated in the design of high-performance carbon-based materials72,73,74. Therefore, we expect that in lightweight composites, we can use the gyroid structure to compensate for the decreased mechanical properties resulting from sewage sludge incorporation. Interestingly, due to the intricate pattern of connected surfaces and passages, gyroid geometries were near-impossible to manufacture until the advent of 3D printing.

We contrast hydrochar composite printed in gyroid geometries with resin alone printed in a traditional rectilinear lattice geometry. Gyroid architectures were also printed with pure resin for comparison. Printed samples, and their respective unit cells, are shown in Fig. 5a-c. With matched unit sizes, we found that across several relative densities, the rectilinear lattice with neat resin demonstrated the highest modulus and tensile strength (Fig. 5d, e). However, both the gyroid prints with neat resin and hydrochar composite surpassed the rectilinear lattice in failure strain and toughness up to relative density of approximately 0.3 (Fig. 5f, g). The neat resin gyroids generally performed better than the hydrochar gyroids as expected. Nevertheless, this demonstrates that geometry can be used to compensate for some material weaknesses when using more sustainable materials, such as in packaging or similar applications where lightweighting and energy absorption may be more important than stiffness.

Conclusion

This study investigated the valorization of sewage sludge with hydrothermal processing and additive manufacturing. A key observation was that the notable presence of metallic and metalloid dopants in sewage sludge, which are not typically found in biomass residues, were retained throughout the hydrothermal process and had a profound multiscale effect on the results of thermal activation to yield materials that are atypical of these processes. Many HTP studies explore the impact of varying HTP conditions on the properties of resulting materials, but here it was observed that the different HTP products varied minimally. Hydrothermal processing of sewage sludge created highly textured hydrochars with coarse microstructure and nanoscale cracks throughout (Fig. 2). Interestingly, dopants of different elements were not spread homogenously throughout the material but tended to congregate in individual particles. Thermal activation typically yields increased porosity, increased carbon content, and enhanced mechanical properties23,75. However, in this case, the dopants likely interfered with typical carbonization reactions and were not pyrolyzable, so thermal activation decreased the relative carbon content in the resulting activated carbons (Fig. 3). Furthermore, the activated carbons demonstrated decreased carbon ordering and aromaticity, smoother nanoscale topology without the presence of cracks, and larger particles with dopant impurities.

As a filler in resin-based additive manufacturing, we found that both hydrochars and activated carbons decreased the stiffness and hardness of composites, which may be attributable to limited adhesion between the printing resin and sewage sludge derivatives. Interestingly, the hydrochar-doped composites performed better than the activated carbon-doped composites, which may result from smaller particle sizes and better resin impregnation due to nanoscale cracks throughout the materials.

These structural and mechanical results present phenomena contrary to typical understanding of biomass HTP and thermal activation, demonstrating that sewage sludge may not be able to be treated like typical biomass residues. This presents potential drawbacks, as much more analysis of sewage-sludge based materials is necessary, as well as opportunities, as new functionalities can be discovered.

Here, we further demonstrated that despite decreased stiffness, hydrochar-doped composites can outperform pure synthetic resin in toughness and failure strain by architecting it in a nature-inspired gyroid geometry, as compared to traditional rectilinear lattices. This phenomenon demonstrates a merger of geometry and material that is common to hierarchical biological materials and shows that sewage sludge can still be successfully used as a sustainable filler to decrease consumption of raw synthetic material. Some potential applications include visual prototyping and packaging, i.e. applications where toughness may be more important than modulus or strength alone. Furthermore, we conclude that sewage sludge hydrochar may not be the best option as a 3D-printing additive, but it is still functional and a good outlet for excess residues that may result from sewage sludge HTP for other applications. If the sewage sludge hydrochar is not already a byproduct, although HTP is considered to be an efficient method for processing biomass, energy consumption should be quantified and weighed against the impacts of raw material usage and solid waste accumulation before being implemented at scale.

In our perspective, it would perhaps be more interesting to further investigate the effects of various dopants on HTP and carbon activation, such as how results would vary with different methods of activation. Mixing sewage sludge with other biomass waste streams could also potentially dilute the dopants enough to enhance carbon ordering or to harness other properties such as conductivity. Understanding how dopants affect functional bio-based materials may have implications on the valorization of various biomass residues, especially as the field of sustainability shifts towards using waste streams that may not have tightly controlled constituents. In fact, it is possible that these dopants may have properties that can yield new functionalities to biobased materials, such as in one study that found that arsenic removal was positively correlated with inorganic content in carbonized waste materials for water treatment52. We present a first foray here and anticipate further research on the valorization of disordered biomass waste streams.

Methods

Hydrothermal processing

Sewage sludge was procured from Bay State Fertilizer (Quincy, MA), which dewaters and pelletizes digested sewage sludge from the Deer Island wastewater treatment plant (Winthrop, MA). The digested sludge is composed of 60-65% primary sludge by weight, with the remainder being secondary sludge.

Batch HTP experiments were carried out with a 1.8 L Parr reactor (Parr Instrument Company, Mode 4578). To the 1.8 L chamber, 200 g (dry weight) of sewage sludge was loaded, and D.I. water was added to reach a solid content of 20% (w w−1). The reactor was tightly sealed and pressurized with pure nitrogen to reach the target initial pressure (0, 10, or 20 bar). The reactor was heated up to the target temperature (250, 300, or 320 °C) at a rate of 3.33 °C min−1, then held at the target temperature for 30 min before cooling down. When the temperature of the reactor dropped below 50 °C, the residual pressure and temperature were recorded before releasing the residual pressure and opening the chamber. The resulting slurry was transferred to a 2 L container, and a small amount of water was used to wash the chamber to recover all slurry. To separate the products, 400 mL dichloromethane (DCM) was added to the slurry and mixed well. The mixture was then filtered through a Büchner funnel with one Whatman GF/B glass filter (diameter 110 mm) with vacuum. The solid cake in the Büchner funnel was rinsed again with 400 mL DCM, then dried at 105 °C overnight to yield the hydrochar. The liquid DCM layer was separated from the aqueous layer, then dried at room temperature in a fume hood to remove the DCM until mass of the mixture plateaued. Finally, the resulting bio-oil was dried at 60 °C for 1 h to remove residual DCM.

Hydrochar and bio-oil yield were calculated as the ratio of the weight of the recovered product mass (mi, where i = hydrochar, or bio-oil) and the dry mass of sewage sludge (msludge) initially loaded to the reactor, according to Eq. (2):

Thermal activation and ball milling

Thermal activation of hydrochar was conducted in a Carbolite Gero tube furnace under continuous flow of nitrogen. For each sample, 4 g of hydrochar was placed in a ceramic crucible. Temperature was ramped from room temperature to 850 °C at a rate of 5 °C min−1, then held at 850 °C for 2 h, after which the furnace was allowed to cool to room temperature before opening. Activated and non-activated samples were ground with a ball-mill (SPEX SamplePrep, 8000 M Mixer/Mill) for 5 min to obtain a fine powder.

Physical and chemical characterization

XPS was performed on a PHI VersaProbe II to evaluate elemental composition and surface chemistry of samples. Milled samples were pressed onto copper tape with a metal spatula, after which excess was tapped off, and mounted on a sample holder. X-rays were generated with a monochromatic aluminum Kα source. Pass energy of 187.85 eV and a 200 µm spot size were used, with a step size of 0.100 eV for high-resolution scans and 0.800 eV for full sweeps. High-resolution spectra were taken for C1s, O1s, and N1s. Data analysis was performed using CasaPXS (Neal Fairley).

Raman spectroscopy was performed with a confocal Raman microscope (Alpha 300Ra; WITec, Germany) using a Nd:YAG laser (λ = 532 nm) and a 50× Zeiss objective. Spectra were acquired from ball milled HC and AC placed on glass microscope slides. The excitation wavelength was calibrated using a silicon wafer standard. For each sample, 10 individual Raman spectra were acquired at random locations with an accumulation time of 20 s per data point and a laser power of 3–4 mW. After background removal, Lorentzian distribution functions were fitted to the spectra to evaluate the D-to-G band intensity ratio (ID/IG) based on the integrated areas. The average crystal planar domain size La was then calculated using the relation formulated by Knight and White55 and based on the work of Tuinstra and Koenig76, using the coefficient 4.4 for the green laser as shown in Eq. (3):

SEM was performed using a Vega3 XMU (Tescan, Czech Republic) SEM. This was paired with a Bruker Xflash 630 silicon drift detector for EDS elemental mapping. High-resolution SEMS were acquired with a Zeiss Merlin High-resolution SEM. Hydrochar samples were gold-sputtered with a Denton Vacuum Desk V (Moorestown, NJ, USA) for 30 s before imaging.

Geometry design

Sample geometries and 3D printing STL files were prepared using nTopology software (nTopology Inc.)77. Compression sample geometries were 12.7 mm (diameter) × 25.4 mm (height) cylinders as designated in ASTM d695, and tensile sample geometries were taken from ASTM d638 Type IV. Bioinspired geometries were 12.7 mm × 12.7 mm × 25.4 mm rectangular prisms and were designed such that gyroid and rectilinear lattices had the same unit cell size, but varying wall thickness to achieve similar relative densities at 8 different points ranging from approximately 0.15 to 0.55. Samples for testing of bulk material properties were prepared at least in triplicate to assess reproducibility.

Resin incorporation and 3D printing

Milled hydrochar and AC samples were mechanically incorporated into Anycubic Plant-based UV photocurable resin. Hydrochar was incorporated at 2% w w−1 with constant stirring at 450 rpm for 30 min. The mixture was then sonicated for 5 min to ensure particle dispersion and stirred for an additional 30 s to reduce bubbles.

Stereolithography 3D printing was executed with a mono LCD printer (Elegoo Mars 2 Pro), where resin is selectively cured layer-by-layer with an LCD screen. After printing, samples were removed from the build plate with a metal spatula, washed of excess resin for 2 min in an ethanol bath, and crosslinked with UV light exposure for 3 min (Elegoo Mercury Plus V2).

After printing, conductivity of pressed powders, powders dispersed in deionized water, and bulk printed materials was assessed with a multimeter.

Mechanical testing

Micro-indentation was performed using an Anton Paar Instruments system. All measurements were conducted with a Berkovich tip. 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm cylindrical samples were 3D printed, and sample surfaces were polished prior to testing using a sequence of polishing pads with reduced abrasiveness. Indentation hardness and indentation modulus were calculated for all data sets using the Oliver-Pharr method78. The specimens were loaded in force-control mode up to the maximum indentation depth limit of 24 μm at a loading rate of 3 N min−1. At the peak load, the force was held constant for 10 s before unloading at a rate of 3 N min−1. Each sample underwent 20 to 25 microindentation measurements.

Compression testing was performed on an Instron universal tensile testing system with a 5 kN load cell and 15 cm platens. Tensile testing was performed on an Instron universal tensile testing system with a 5 kN load cell and pneumatic grips.

Responses