Shaking the Tibetan Plateau: Insights from the Mw 7.1 Dingri earthquake and its implications for active fault mapping and disaster mitigation

Introduction

Earthquakes, as one of the most devastating natural disasters, pose significant risks to human life, infrastructure, and the environment. The sudden release of energy during seismic events can result in catastrophic destruction, including building collapses, landslides, tsunamis, and widespread societal disruption. Particularly in densely populated areas or regions with inadequate preparedness, earthquakes can lead to immense loss of life and long-term economic impacts1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. The Tibetan Plateau, a region formed by the continuous collision between the Indian and Eurasian Plates, is not only known as the “Third Pole” due to its extreme elevation, but also as one of the most seismically active areas in the world. The complex tectonic setting results in some of the highest rates of crustal deformation, the most active fault systems, and frequent earthquake occurrences globally12,13,14,15,16,17,18. This ongoing tectonic activity has transformed the region into a natural laboratory for the study of earthquake dynamics and their associated geohazards. Since the beginning of the 21st century, the plateau has been struck by several major earthquakes, including the 2001 Mw7.8 Hoh Xil earthquake, the 2008 Mw7.1 Yutian earthquake, and the devastating 2008 Mw7.9 Wenchuan earthquake, along with numerous other significant seismic events12,13,15,17,19,20,21. While earthquakes along the margins of the Tibetan Plateau and in surrounding areas have caused extensive casualties and property damage, seismic activity within the plateau’s interior, such as the 2001 Hoh Xil and 2008 Yutian earthquakes, has resulted in relatively minimal destruction15,21,22.

A recent destructive earthquake, known as the “Dingri earthquake,” struck Dingri County in the Tibet Autonomous Region on January 7, 2025. The epicenter, located in Cuoguo Township (87.45°E, 28.50°N), had a surface wave magnitude (Ms) of 6.8, with a focal depth of 10 km. As of January 14, 2025, a total of 3614 aftershocks were recorded, with the largest aftershock reaching magnitude M5.0. Interestingly, while the China Earthquake Networks Center (CENC) reports the earthquake’s Ms6.8, the United States Geological Survey (USGS) has determined the moment magnitude (Mw) to be Mw7.1. This discrepancy highlights the complexities in earthquake magnitude measurement and the ongoing debate within the seismological community. This paper provides an overview of the tectonic environment and disaster characteristics of the Dingri earthquake.

Tectonic setting

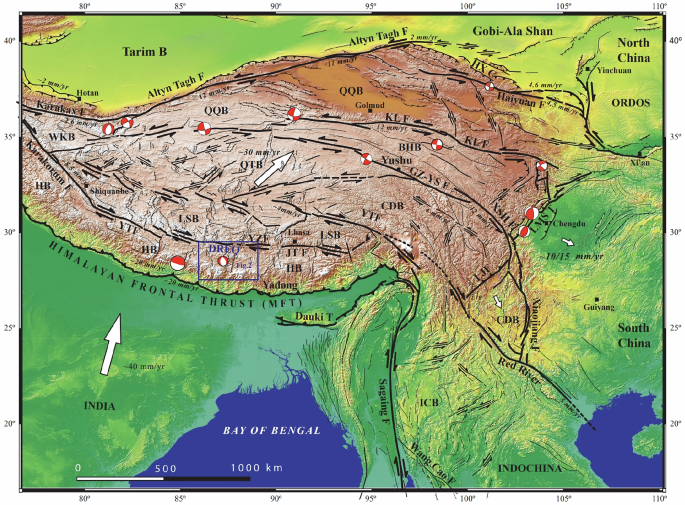

Figure 1 illustrates the key active tectonic features of the Tibetan Plateau, characterized by convergence structures accommodating crustal shortening and thickening around the plateau margins, mega strike-slip faults enabling horizontal shear and eastward block extrusion primarily in the central and eastern regions, and east-west (EW)-trending extensional structures supporting the movement of blocks in the western and central plateau9,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. The convergence structures include the Himalayan Frontal Thrust (MFT) along the southern margin and the Qilian-Hexi Corridor, Liupanshan, and Longmenshan reverse fault-fold belts along the northeastern, eastern, and southeastern margins, respectively (Fig. 1). Major strike-slip faults include the left-lateral Altyn Tagh, Haiyuan, East Kunlun, Garzi-Yushu, and Xianshuihe faults in the eastern and northern plateau, along with the right-lateral Jiali and Karakorum faults in the western and southern regions. These faults generally exhibit Holocene slip rates ranging from 2 to 12 mm/yr21,32,33,34,35. Extensional structures are defined by numerous north-south (NS)-trending normal faults and NW- and NE-trending conjugate strike-slip faults in the central and western plateau (Fig. 1). Vertical slip rates for individual normal faults are generally less than or near 1 mm/yr, while conjugate strike-slip faults can reach rates of 3.5 ± 1.2 mm/yr28,36. These patterns indicate local EW-trending crustal extension under NS compression and shortening21,26,37,38. The southern plateau hosts seven rift systems controlled by NS-trending normal faults, with extensional rates reaching up to 9 ± 2 mm/yr31,32,36.

DREQ represent the Dingri earthquake and its focal mechanism solution; fine lines with bars on the hanging walls represent normal faults; course lines with black-triangles on the hang walls represent reverse faults; course lines with horizontal arrows represent strike-slip faults. KLF Kunlun fault, GZ-YSF Ganzi-Yushu fault, XSHF Xianshuihe fault, JLF Jiali fault, YTF Yarlung Tsangpo fault, HB Himalayan block, LSB Lhasa block, QTB Qiangtang block, CDB Sichuan-Yunnan block, BHB Baryan Har block, QQB Qaidam-Qilian block, WKB West Kunlun block, HX Hexi Corridor. The dark blue rectangle box shows extent of Fig. 2.

Present-day tectonic activity shows eastward block extrusion at rates up to ~20 mm/yr between the Jiali and Ganzi-Yushu faults, while westward extrusion peaks at ~6 mm/yr in the Pamir-Hindu Kush region34. This tectonic regime results in reverse faulting earthquakes along the Himalayan Frontal Thrust (MFT), Qilian Shan-Hexi Corridor, and Longmenshan belts, while pure-shear events are common along the strike-slip faults. In contrast, the central and western plateau are predominantly characterized by normal faulting events21,22,39,40,41,42. The Dingri earthquake, located near the western boundary of the Shenzha-Dingjie Rift (Figs. 1 and 2), was triggered by the NS-trending Dengme Co fault. This typical west-dipping normal fault exhibits downward movement of the western wall and uplift of the eastern wall, with a minor strike-slip component.

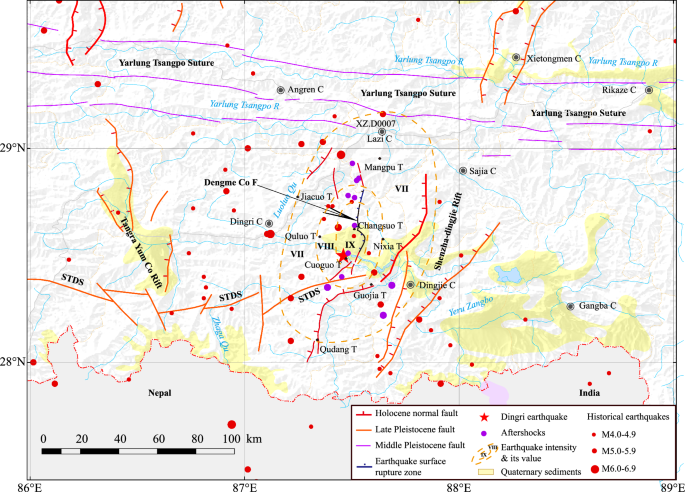

Black line with bars on the west represents the surface rupture zone of the Dingri earthquake along the Dengme Co fault; red lines indicate active faults; purple lines denote faults within the Yarlung Tsangpo suture; a red star locates the epicenter determined by CENC; red solid circles are historical instrumental earthquakes with Ms4-7; purple solid circles indicate the aftershocks of the Dingri earthquake (M3.0-5.0). Location is shown by a dark blue rectangle box in Fig. 1.

Seismogenic fault of the Dingri earthquake

Based on focal mechanism solutions from the China Earthquake Networks Center (CENC) and the Global Centroid Moment Tensor (GCMT), the seismogenic fault of the Dingri earthquake is inferred to be a north-south (NS)-trending normal fault dipping westward at approximately 50°. Rapid inversion analysis of the rupture process, conducted by the Geophysics-Source Research Group at Peking University, reveals that coseismic slips primarily occurred in the upper portion of the fault, between depths of 0 and 10 km. Integrating the spatial distribution of aftershocks, the study concluded that the initial rupture originated at the southern end of the seismogenic fault (Fig. 2) and propagated unilaterally northward, with increasing coseismic slip from south to north. It is speculated that the Dengme Co fault, a major active structure controlling Dengme Co (Lake), was fully involved in the rupture process, resulting in a vertical coseismic slip of approximately 0.5 meters along the eastern shore of the lake. Notably, the northern segment of the Dengme Co fault, situated within a north-south trending valley northeast of Longsuo Township, exhibits prominent surface ruptures, with a maximum coseismic slip of approximately 3 meters.

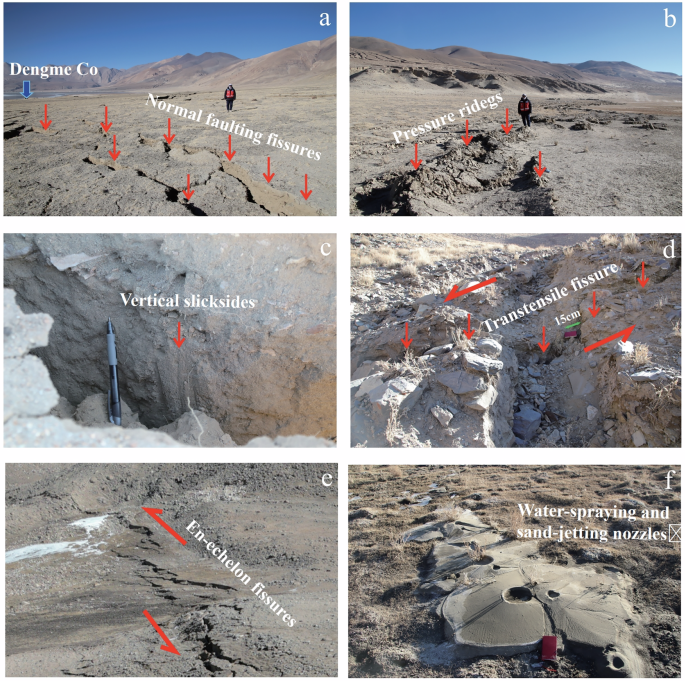

Preliminary field investigations (Fig. 3) identified an arc-shaped rupture zone approximately 11 km long along the eastern shore of Dengme Co, featuring predominantly NE-, NNE-, and NW-trending tensional or transtensional fissures and pressure ridges (Fig. 3a, b). The fissures are distributed over a width of up to 100 m. These surface features are presumed to result from the combined brittle responses of near-surface frozen lacustrine deposits to subsurface normal fault slip, earthquake vibrations, and gravitational forces. Along this arc-like rupture zone, identifying or accurately measuring coseismic vertical slip proves challenging. However, slickensides observed on the normal fault near Changsuo Township, north of Dengme Co, indicate that the surface rupture was predominantly characterized by normal faulting with a minor left-lateral strike-slip component (Fig. 3c). Additionally, a small gully crossing the rupture zone near the range front showed an oblique offset, with a visible left-lateral slip of approximately 15 cm (Fig. 3d). Further north, within the mountainous area northeast of La’ang Reservoir, the rupture zone consists of en-echelon transtensional fissures (Fig. 3e), also displaying a left-lateral strike-slip component with localized features. Using DEM data from the Chinese Gaofen-7 satellite, acquired before and after the Dingri earthquake, researchers at the Institute of Earthquake Forecasting, China Earthquake Administration (IEF, CEA), determined an average vertical offset of 2 m, with a maximum offset of up to 3 m. Field investigations and slip measurements43 confirmed these findings. Assuming a fault dip angle of 50°, the maximum coseismic vertical slip of 3 meters corresponds to an east-west crustal extension of approximately 2.5 m, aligning with the region’s ongoing crustal extension34.

a Distributed tensional fissures on the east shore of Dengme Co, view to north; b Pressure ridges illustrating local shortening on the east shore of Dengme Co, view to southeast; c Slickenside striations illustrating dominant normal faulting with a small left-lateral component on the northeast shore of Dengme Co; d Offset gully illustrating a left-lateral slip of about 15 cm at the range front northeast of Changsuo Township, view to northwest; e En-echelon surface ruptures illustrating a left-lateral component northeast of the La’ang Reservoir, view to east; f Water-spraying and sand-jetting nozzles on the east shore of Dengme Co.

Thus, the surface rupture zone of the Dingri earthquake extends from the southern end along the eastern shore of Dengme Co, continuing northward through the mountainous valley north of Changsuo Township, following the trace of the Dengme Co fault. The total length of this rupture zone is estimated to be between 25 km and 32 km (Fig. 2).

Analysis of causes of heavy earthquake disaster

The Tibetan Plateau historically experienced a significant normal faulting earthquake in 2008, the Mw7.1 Yutian earthquake, which occurred in the western Kunlun Mountains. Field investigations documented a surface rupture zone extending approximately 31 km, with a maximum vertical offset of about 3.3 m. Notably, no casualties or property damage were reported21. The moment magnitude (Mw7.1) of the Dingri earthquake is comparable to that of the 2008 Yutian event. However, the densely populated epicentral area of the Dingri earthquake, which covers numerous towns and villages, resulted in severe disaster impacts. As of January 9, 2025, the earthquake had caused 126 casualties and the collapse of 3612 houses. It affected 26 towns and townships across Dingri, Lazi, Sajia, Dingjie, and Angren Counties (Fig. 2). According to the earthquake intensity map released by the China Earthquake Administration (CEA), the highest intensity reached IX, covering 411 square kilometers, primarily in Changsuo, Quluo, Cuoguo, Nixia, and Jiacuo Townships of Dingri County (Fig. 2). The seismic intensity VIII zone covers about 869 square kilometers, involving Quluo, Changsuo, Cuoguo, Nixia, Jiacuo, and Qudang Townships in Dingri County, GuoJia in Dingjie County, and Manpu and eight other townships in Lazi County. The intensity VII area spans approximately 5350 square kilometers, involving 20 townships.

The severity of the disaster can be attributed to several factors. First, the earthquake’s large magnitude and shallow focal depth generated strong ground shaking. According to the report of Institute of Engineering Mechanics, China Earthquake Administration, the data from the XZ.D0007 seismic intensity meter (87.63°E, 29.09°N) in Quxia Town, Lazi County, 67.5 km from the epicenter, recorded a peak horizontal ground acceleration of 395 cm/s², exceeding local seismic fortification standards. Second, the Dengme Co Basin near the epicenter contains thick layers of silt and sandy soil, which amplified ground motion and triggered liquefaction during the earthquake (Fig. 3f). Third, the Dengme Co fault, responsible for the Dingri earthquake, traverses Cuoguo and Changsuo Townships, with the basin’s poor site conditions amplifying seismic intensity. Fourth, traditional Tibetan-style soil-stone houses prevalent in rural areas have poor seismic performance, contributing to large-scale collapses and higher casualties.

Earthquake-induced landslides are a significant hazard in mountainous regions during strong seismic events, as evidenced by the 2008 Wenchuan, China Earthquake44, the 2013 Lushan, China Earthquake45, the 2015 Gorkha, Nepal Earthquake46,47, and the 2022 Luding, China Earthquake48,49, all of which triggered numerous landslides across the Tibetan Plateau and its periphery. However, the recent Dingri Earthquake did not result in severe landslides. This can likely be attributed to several factors. Firstly, unlike typical earthquakes with strong landslide-triggering potential, the epicenter of this event was located in the interior of the plateau, where the terrain is relatively gentle, with limited elevation changes and moderate slopes. Secondly, the seismogenic fault of this earthquake was a normal fault, which generally has a weaker capacity to trigger geological hazards compared to reverse faults. Additionally, the timing of the earthquake in winter may have played a crucial role, as the potential frozen state of the surface likely increased slope stability and reduced landslide susceptibility. A similar phenomenon was observed during the January 8, 2022, M6.9 Menyuan Earthquake12 in Qinghai, China where the low temperature was considered a key factor in suppressing the development of coseismic landslides. Although the Dingri, China Earthquake did not cause significant landslides, this does not imply that the landslide risks in similar regions can be disregarded. The presence of numerous landslide relics in the area suggests a potential link to historical or paleo-seismic events50. This highlights the need for a comprehensive approach to earthquake disaster mitigation, including active fault detection, seismic risk assessment, structural resilience improvement, secondary disaster prevention, and the enhancement of high-altitude emergency response capacities.

Conclusions and suggestions

The Dingri earthquake on January 7, 2025, was a typical normal faulting event along the Dengme Co fault, with a surface rupture zone extending approximately 25 to 32 km. The maximum vertical slip reached up to 3 m, with a minor left-lateral strike-slip component. The disaster’s severity can be attributed to several key factors: strong ground shaking, significant liquefaction within the basin, distributed surface ruptures along the seismogenic fault affecting Changsuo and Cuoguo Townships, and the vulnerability of traditional Tibetan-style soil-stone houses. To mitigate the risk of similar earthquake disasters on the Tibetan Plateau, the following measures are recommended:

-

Active Fault Mapping and Geological Monitoring: Intensify efforts to comprehensively map active faults and identify unfavorable geological conditions.

-

Structural Resilience: Improve the seismic performance of rural housing, particularly in high-risk zones, by promoting earthquake-resistant construction techniques.

-

Secondary Disaster Prevention: Enhance monitoring and early warning systems for earthquake-induced hazards such as landslides and glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs). Strengthen emergency response plans to address these threats effectively.

These proactive measures will be essential in reducing the impact of future seismic events and improving the region’s disaster resilience.

Responses