Site-designed dual-active-center catalysts for co-catalysis in advanced oxidation processes

Introduction

A significant issue has arisen due to sewage containing refractory organic matter, notably emerging contaminants (ECs) such as pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and surfactants, which has resulted in severe pollution of both surface and groundwater, especially in developing countries1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Consequently, extensive protocols have been developed to eliminate ECs in water matrices. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have emerged as one of the most promising technologies for water decontamination and disinfection10,11,12,13,14. AOPs produce high-valent metal species and reactive oxygen species (ROS), comprising hydroxyl radicals (•OH), sulfate radicals (SO4•⁻), superoxide radicals (O2•⁻), and singlet oxygen (1O2), which effectively oxidize and mineralize refractory organic pollutants15,16,17,18,19,20,21. The key to generating ROS lies in the activation of common oxidants, such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and peroxymonosulfate (PMS), through various catalytic methods22,23,24,25. Therefore, precise design and control of catalytic sites are of utmost importance for the advancement AOPs26,27,28,29. Recently, a variety of single-active-center catalysts have been developed for the activation of various oxidants, with the merits of30,31,32: (1) outstanding activity and selectivity caused by the unique electronic structures; (2) controllable orientation of target ROS and easy identification of mechanism due to the well-defined single site. However, the inherent limitations of single-active-center catalysts in catalyzing complex reactions remain. Due to the structural monotony of active center, single-active-center catalysts suffer from the limitation of scaling relations between the adsorption energies of similar adsorbates (i.e., the adsorptions of an adsorbate and its derived molecules on the identical site are either all strong or all weak)33. This makes it difficult for single-active-center catalysts to find a thermodynamic balance between strongly adsorbing reactants, efficiently activating intermediates and easily desorbing products. Therefore, in the complicated catalytic oxidation process involving multiple intermediates (e.g., electro-Fenton (EF): *OOH, *H2O2; PMS Fenton-like: *SO4, *OH, *O) and reaction steps, energetically unfavorable step or high energy barrier may exist34. A promising strategy to address these issues is the development of dual-active-center co-catalysts, which combine the advantages of single-active-center catalysts while offering synergistic possibilities between the two active centers34,35.

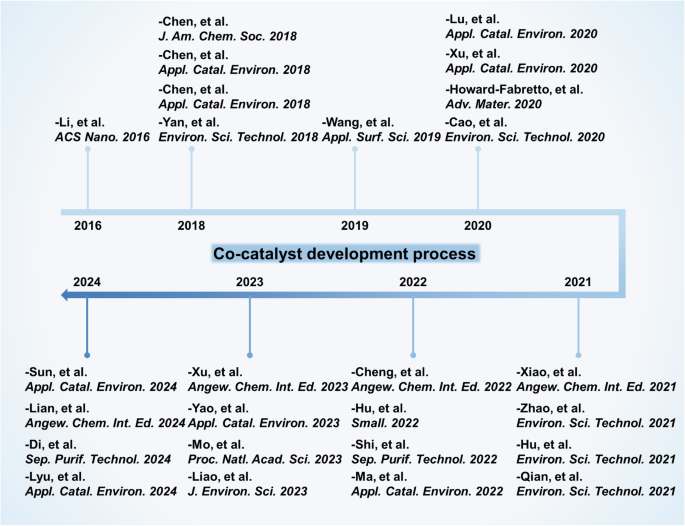

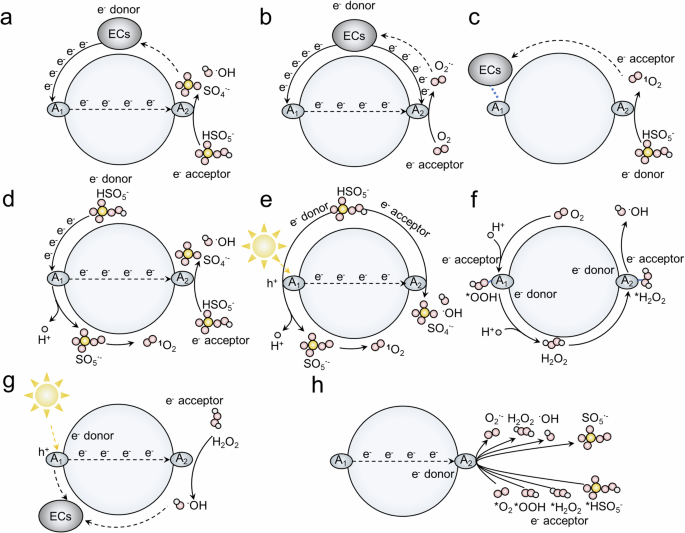

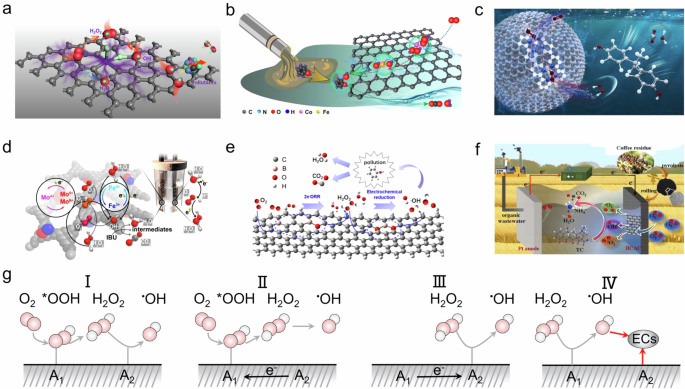

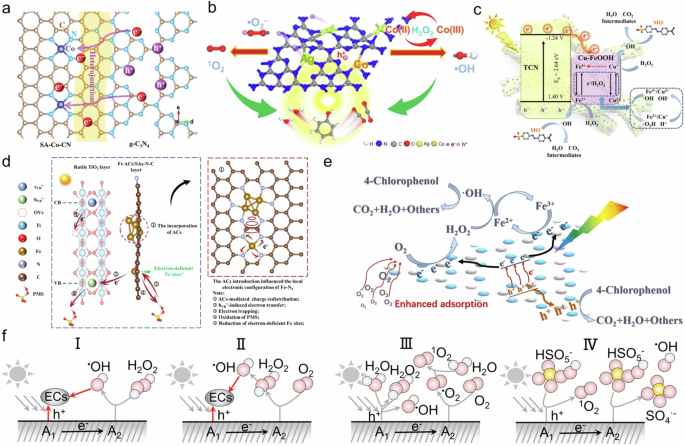

Figure 1 displays the timelines for the development of dual-active-center co-catalysis in AOP systems. Dual-active-center co-catalysis, involves additional catalytic sites (active site A1) working in concert with primary catalyst sites (active site A2) to boost overall catalytic performance36,37,38,39,40,41. Currently, research on dual-active-center co-catalysis is still in its early stages, with most studies focusing on catalyst structural design. No comprehensive review exists on the types and design principles specific to co-catalysis in AOPs catalysts, and the systematic comparison and elucidation of the catalytic mechanisms of dual-active-center co-catalysis in AOPs systems are highly appreciated. Fundamentally, several key types of dual-active-center co-catalysts involved in AOPs are summarized in Fig. 2: (1) ECs act as electron donors to drive co-catalysis between active site A1 and active site A2 (Fig. 2a, b)42; (2) Active site A1 adsorbs ECs while active site A2 generates ROS for co-catalytic ECs degradation (Fig. 2c)43; (3) PMS serves as an electron donor, facilitating co-catalysis between active site A1 and active site A2 (Fig. 2d, e)44,45; (4) In the EF process, active sites A1 and A2 co-catalysis in a 3-electron transfer pathway (O2 to •OH radical) (Fig. 2f)29; (5) In photo-Fenton systems, active site A1 generates hole (h+), which cooperates with active site A2 to degrade ECs (Fig. 2g)45; (6) Active site A1 modulates the adsorption and binding energy of oxidants/intermediates at active site A2 in Fenton/Fenton-like systems (Fig. 2h)46,47,48,49. Clearly, the integration of co-catalysis into AOPs offers new opportunities for catalyst design. To enhance the specificity and performance of catalysts for particular applications, such as targeting specific pollutants or operating under distinct environmental conditions, researchers can meticulously select and engineer the interactions between active sites.

The figure depicts the typical representatives of co-catalysts in AOPs from 2016 to 2024.

a, b ECs act as electron donors to drive co-catalysis between active site A1 and active site A2. c Active site A1 adsorbs ECs while active site A2 generates ROS for co-catalytic ECs degradation. d, e PMS serves as an electron donor, facilitating co-catalysis between active site A1 and active site A2. f In the EF process, active sites A1 and A2 co-catalysis in a 3-electron transfer pathway (O2 to •OH radical). g In photo-Fenton systems, active site A1 generates hole (h+), which cooperates with active site A2 to degrade ECs. h Active site A1 modulates the adsorption and binding energy of oxidants/intermediates at active site A2 in Fenton/Fenton-like systems. The pink spheres represent oxygen atoms, the white spheres represent hydrogen atoms, the yellow spheres represent sulfur atoms, the dark gray elliptical spheres represent pollutants (ECs), the light gray elliptical spheres represent active sites A1 and A2, and the sunlight represents the light for photocatalysis.

In this review, we aim to provide a fundamental understanding of co-catalytic dual-active-center interactions in AOPs catalysts and highlight the opportunities for designing and developing the desirable catalysts. Firstly, we show the characterization techniques for dual-active-center catalysts, and then provide an overview of the synthetic approaches that have been reported to achieve different dual-active-center catalysts. Secondly, we discuss the concept of co-catalytic interactions in the binding of species in each specific reaction (EF, photocatalytic, PMS-based, and pollutant-as-electron-donor (PED) based Fenton-like systems) and how these binding effects can fundamentally impact the catalytic performance. Thirdly, we discuss the significant impact of active site distance and density on the effectiveness of co-catalysis. Lastly, we outline the challenges, opportunities, and future prospects for dual-active-center catalysts research, emphasizing the potential to fully harness the benefits of co-catalysis in creating the next generation of catalyst materials.

Synthetic strategies and characterization techniques for dual-active-center catalysts

Synthetic strategies

To obtain materials with well-defined dual-active-center sites, a carefully designed synthesis strategy is required. As summarized in Table 1, we review the synthesis methods for designing co-catalytic dual-active-center catalysts in EF, photocatalytic, PMS-, and PED- based Fenton-like systems. Techniques such as impregnation and pyrolysis, pre-coordination and pyrolysis, anchoring and pyrolysis, ball-milling, ball-milling followed by pyrolysis, self-assembly and pyrolysis, copolymerization and pyrolysis, as well as pyrolysis combined with hydrothermal treatment, can be further optimized to produce various types of dual-active-center catalysts25,42,43,50,51,52,53,54,55. These methods enable the synthesis of catalysts such as single atom catalysts (SACs)-nonmetal, SACs-metal clusters, dual atom catalysts (DACs), metal-metal clusters, nonmetal-metal clusters, and nonmetal-nonmetal clusters.

For the synthesis of SACs-nonmetal dual-active-center catalysts, there are generally two methods: the impregnation and pyrolysis method, and the pre-coordination and pyrolysis method43,50. In the EF system, Cao et al. recently reported the synthesis of co-catalytic dual-active-center catalysts (C3–Fe–Cl2 catalysts) using impregnation and pyrolysis methods13. The authors first synthesized Cu/MIL-88B (Fe) via a modified hydrothermal method. This was followed by high-temperature pyrolysis to form SACs. It should be noted that specific structures of C3–Fe–Cl2 can be formed, utilizing Cl to modulate the adsorption energy of *H2O2 at the Fe sites. Moreover, Yang et al. reported a co-catalytic dual-active-center catalyst (Fe1/TiO2 SACs) using impregnation and pyrolysis methods in the Photo-Fenton/Photo-Fenton-like system56. They first prepared TiO2 with varying oxygen vacancy (OV) content by controlling the hydrothermal temperature. Subsequently, Fe2+ was mixed with TiO2 and calcined to obtain the Fe1/TiO2 SACs. This catalyst contains -OH functional groups that selectively adsorb phenol. The Fe and OV sites then utilize photogenerated electrons to activate PMS, generating active species to degrade phenol. In the PMS Fenton-like processes, Li et al. reported a co-catalytic dual-active-center catalyst using pre-coordination and pyrolysis methods43. The catalyst was first pre-coordinated using a Prussian blue analog structure, followed by high-temperature pyrolysis to obtain the Co SACs. In this catalyst, the pyrrole nitrogen facilitates the adsorption of the pollutant bisphenol A (BPA), while the Co single-atom sites activate PMS, enabling co-catalysis between the Co sites and pyrrole nitrogen sites. Furthermore, in Fenton-like systems where pollutants serve as the electron donors, Cao et al. reported a novel process for rapid salinity-mediated water self-purification in a dual-reaction-center system with cation–π structures46. In this system, g-C3N4 and Fe ions were impregnated and pyrolyzed to obtain nZVI/FeOx/FeNy-anchored aromatic cation–π framework composites, which were applied to the rapid salinity-mediated water self-purification process.

For the synthesis of SACs-metal cluster catalysts, it is typically advantageous for the metal species to be identical within the catalyst. Introducing a different metal may lead to undesirable metal agglomeration, thereby hindering the formation of dual-active-center catalysts with single-atom and metal-cluster structures57. In the EF system, Xu et al. recently reported the synthesis of co-catalytic dual-active-center catalysts (FeO4/Fe4/C catalysts) by mixing bacterial cellulose aerogel with Fe3+, followed by high-temperature pyrolysis58. This approach yields a catalyst that features the coexistence of Fe clusters and Fe SACs. The authors achieved co-catalysis by introducing Fe clusters to modify the adsorption energy of *OOH at the Fe single-atom sites, thereby enabling co-catalysis between the Fe clusters and Fe single atoms. In the PMS Fenton-like processes, Mo et al. reported a co-catalytic dual-active-center catalyst (Fe SACs/Fe Clusters catalyst) prepared using impregnation and pyrolysis methods45. The introduction of Fe clusters induced a charge redistribution within the Fe SACs, thereby enhancing the interaction between the Fe SACs and PMS. Simultaneously, the Fe clusters optimized the HSO5⁻ oxidation and SO5•⁻ desorption steps, accelerating the overall reaction process.

For the synthesis of DACs, three common methods are typically employed: impregnation and pyrolysis, pre-coordination and pyrolysis, and anchoring and pyrolysis methods. In the EF system, Qin et al. proposed a CoFe DACs synthesized via impregnation and pyrolysis methods to cooperatively catalyze •OH electro-generation29. In this catalyst, atomically dispersed Co sites are designated to enhance the reduction of O2 to H2O2 intermediates, while Fe sites are responsible for the subsequent activation of the generated H2O2 to produce •OH radicals. Additionally, Zhao et al. employed similar impregnation and pyrolysis methods to synthesize bifunctional Fe/Cu bimetallic SACs anchored on N-doped porous carbo for the EF process59. In this system, chlorinated pollutants are first dechlorinated at the single-atom Cu sites and subsequently oxidized by •OH radicals generated from the O₂ reduction at the single-atom Fe sites. Benefiting from the synergistic effect between dechlorination on single-atom Cu and •OH oxidation on single-atom Fe, the chlorinated organic pollutants are efficiently degraded and mineralized. Sun et al. reported a co-catalytic dual-active-center catalyst (CoFe-DACs) synthesized using pre-coordination and pyrolysis methods60. The catalyst was first pre-coordinated with a Prussian blue analog structure, followed by high-temperature pyrolysis to obtain the CoFe-DACs. In this catalyst, the Co active sites selectively bind *OOH, while the Fe active sites selectively bind *H2O2, thereby enabling a 2e⁻ oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) coupled with a 1e⁻ Fenton reaction for tandem catalysis. In the photo-Fenton/photo-Fenton-like processes, Lian et al. employed impregnation and pyrolysis methods by first mixing melamine with cyanuric acid, followed by the addition of Ag+ and Co2+ ions61. The mixture was then stirred, centrifuged, and subsequently calcined to obtain a high-density (Ag: 22.0 wt%) of atomically dispersed AgCo dual sites embedded in graphitic carbon nitride, which was applied in the photo-Fenton system. In the PMS Fenton-like processes, Wang et al. reported Fe-Co DACs synthesized via impregnation and pyrolysis methods42. This catalyst features a unique FeCo−N6 structure, which achieves a nearly 100.0% electron transfer process (ETP) for highly efficient PMS activation by regulating the PMS adsorption mode. Moreover, Cheng et al. employed anchoring and pyrolysis methods, where Fe(phen)3 was first anchored onto Nano-MgO, followed by pyrolysis to obtain Fe−Fe DACs25. This approach allows for precise control of the Fe−Fe distance, enabling accurate coordination with PMS molecules of similar spacing, thereby facilitating the cleavage of the peroxide bond in PMS.

For the synthesis of metal-metal cluster catalysts, three common methods are typically employed: impregnation and pyrolysis, ball-milling treatment, and ball-milling treatment and pyrolysis methods. In the EF system, Hu et al. reported the synthesis of a core-shell structural Fe-based catalyst via impregnation and pyrolysis methods62. This catalyst demonstrated the predominant role of Fe3C in H2O2 generation and the beneficial effect of FeNx sites in the activation of H2O2 to produce •OH radicals. Additionally, Dong et al. synthesized dual-functional atomically dispersed Mo–Fe sites embedded in carbon nitride (C3N5) (MoFe/C3N5) using impregnation and pyrolysis methods63. Density functional theory (DFT) analysis revealed that the dual-functional MoFe/C3N5 catalyst facilitated a synergistic interaction between the Mo–Fe dual single atomic centers, which could modify the adsorption/dissociation behavior and reduce the overall reaction barriers, leading to effective organic oxidation during the EF process. In the photo-Fenton/photo-Fenton-like processes, Shi et al. fabricated a series of magnetic MgFe2O4/MIL-88A catalysts via ball-milling treatment, which were employed to degrade the antibiotic sulfamethoxazole under low-power visible light in a photo-Fenton process50. The exceptional catalytic activity of the MgFe2O4/MIL-88A catalyst can be attributed to the efficient charge carrier transfer between MgFe2O4 and MIL-88A. Additionally, the optimized MgFe2O4/MIL-88A catalyst exhibited excellent stability and recyclability. In the PMS Fenton-like processes, Zhao et al. reported a co-catalytic dual-active-center catalyst (Fe3C/Fe@N–C–x catalyst) prepared using ball-milling treatment and pyrolysis methods51. The catalyst was initially synthesized by mixing MIL-88B (Fe) with melamine, followed by high-temperature pyrolysis to produce a co-catalytic dual-active-center catalyst featuring the coexistence of Fe3C clusters and Fe@N clusters. This catalyst exhibited excellent activation of PMS for the ultrafast elimination of various emerging organic contaminants with high mineralization capacities.

For the synthesis of nonmetal-metal cluster catalysts, three common methods are typically employed: impregnation and pyrolysis, copolymerization and pyrolysis, and pyrolysis and hydrothermal methods. In the EF system, Xiao et al. reported the synthesis of FeCoC by controlling the introduction of iron/cobalt acetylacetonate during the copolymerization and pyrolysis of phenolic polymer aerogels derived from resorcinol and formaldehyde52. The graphite shell with exposed -COOH groups facilitates the 2-electron reduction pathway for H2O2 generation, which is followed by a 1-electron reduction step leading to the production of •OH radicals. In the photo-Fenton/photo-Fenton-like processes, Qian et al. fabricated dual-active-center ZnO@FePc photo-Fenton catalysts with high-speed electron transmission channels through surface hydroxyl-induced assembly64. The catalyst was obtained by combining ZIF-8 with FePc using impregnation and pyrolysis methods. The ZnO@FePc catalyst demonstrated superior performance for the photo-Fenton degradation of ibuprofen, achieving a degradation rate exceeding 90.0% within just 10 min under simulated sunlight. The exceptional performance of the ZnO@FePc catalyst is primarily attributed to the synergistic effect between the dual reaction centers of ZnO and FePc. In the PMS Fenton-like processes, Ma et al. reported the preparation of a yolk@shell nanoreactor using impregnation and pyrolysis methods65. This nanoreactor features Kirkendall effect-induced abundant hollow CoO nanoparticles encapsulated inside a Co, N atoms co-doped graphitized carbon shell. Due to the full utilization of active sites in the yolk@shell nanoreactor, nearly 100.0% PMS activation efficiency was achieved, and 80.0% of tetracycline (50 mg/L) was degraded within 40 min. Furthermore, Lyu et al. reported a twofold cation–π-assembled catalyst consisting of honeycomb microsphere-like MoS2 cross-linked with a g-C3N4 hybrid, synthesized through pyrolysis and hydrothermal methods53. This catalyst was developed to address the bottleneck of excessive resource and energy consumption in Fenton chemistry. It was found that the electrons from pollutants can be captured by H2O2 and O2 via the twofold cation–π interaction during the Fenton-like reaction, inhibiting the oxidative decomposition of H2O2 and enhancing its hydroxylation. Additionally, Liao et al. synthesized a novel Fenton-like catalyst (Cu-PAN3) through impregnation and pyrolysis methods, using coprecipitation and carbon thermal reduction66. The catalyst exhibited excellent Fenton-like catalytic activity and stability for the degradation of various pollutants with minimal H2O2 consumption.

For the synthesis of nonmetal-nonmetal catalysts, three common methods are typically employed: impregnation and pyrolysis, one-step pyrolysis, and copolymerization and pyrolysis methods. In the EF system, Zhang et al. reported the preparation of nitrogen self-doped biochar using impregnation and pyrolysis methods67. During the pyrolysis process, endogenous nitrogen transitioned from edge-doping to graphite-doping. Notably, nitrogen vacancies (NV) began to form when the peak temperature exceeded 700 °C. Structural characterization and DFT calculations indicated that graphitic nitrogen was a critical site for H2O2 generation, while both graphitic nitrogen and pyridinic nitrogen acted as electroactive sites for the activation of H2O2 to •OH. Graphitic nitrogen and NV, with their enhanced capabilities for O2 adsorption and electron trapping, were identified as the electroactive sites for the formation of 1O2 and •O2⁻. In photo-Fenton/photo-Fenton-like processes, Jing et al. reported B-doped g-C3N4 synthesized via a self-assembly and pyrolysis method54. Heteroatom B doping increased the molecular dipole, while morphological engineering exposed additional active sites and optimized band structures. Together, these effects enhanced charge separation and mass transfer between phases, leading to efficient in-situ H₂O₂ production, accelerated Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ valence cycling, and improved hole oxidation. In the PMS Fenton-like processes, Hou et al. prepared a waste plastic-derived catalyst via one-pyrolysis, using g-C3N4 as a self-sacrificial soft template and plastic as a carbon precursor to synthesize graphene-like nanosheets55. Notably, this catalyst achieved 100.0% sulfadiazine removal within 180 s through PMS activation, demonstrating significantly higher catalytic activity compared to previous studies. Additionally, Xie et al. reported a boron and nitrogen co-doped porous carbon material (B-NPC) synthesized via impregnation and pyrolysis methods68. The B species, pyridinic N, and graphitic N within the carbon matrix played key roles in activating PMS and degrading tetracycline. The metal-free B-NPC catalyst also exhibited excellent reusability and notable adaptability to various pollutants.

Characterization

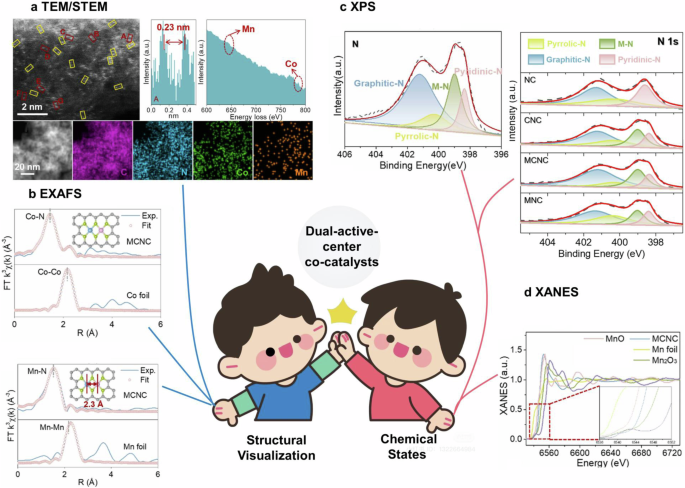

Precise characterization of dual-active-center catalysts plays a central role in the identification of active sites and further establishment of reliable structure-activity relationships. In recent decades, various techniques were developed that enabled atomic-level interrogation of the nature of active sites (e.g., geometric and electronic structures)69,70,71. Here, we focus on a few approaches as demonstrated in Fig. 2 which are sensitive towards the dual-active-center structures, including transmission electron microscopy (TEM)/scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM), extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS), DFT, X-ray diffraction (XRD)/Raman spectroscopy (Raman), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)/X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES).

Structural visualization

TEM, especially high-resolution aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-HAADF-STEM), is crucial for elucidating the geometry of dual-active-center catalysts due to HAADF-STEM unique capability to distinguish the contrast of z number for active center element68. Typically, heavier metal atoms (with higher Z numbers) located on a lighter, uniform support appear as bright dots in dark-field images30. When the active centers in dual-active-center catalysts are composed of metals, they can be easily observed using STEM. For instance, Fig. 3a displays a representative example of Mn-Co pair sites identified by STEM as reported by Christopher and colleagues69. The intensity profile in the HAADF-STEM image reveals the formation of Mn-Co pair sites based on element-specific electron scattering cross-sections. Additionally, element-specific energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) provide information about atomic structure and chemical properties, further aiding in the identification of metal pairs. Additionally, non-metallic dual-active-center catalysts cannot be structurally visualized using TEM/STEM. Further structural details can be extracted from the average bond length measured by line-scan intensity profiles of numerous paired sites, which can assist in determining detailed bonding structures when combined with X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and DFT techniques, as discussed in the following section. However, for catalysts without metal active centers, TEM/STEM might only provide morphological characteristics and may not be as intuitive as in metal-containing catalysts.

a Geometric characterization by TEM/STEM. b EXAFS fitting. c and (d) XPS/XANE69. Copyright 2023 Elsevier B.V.

EXAFS investigates local coordination environment. By fitting the EXAFS spectra with bonding paths from reference samples, one can estimate the coordination number and bonding environment38,39. Based on model obtained from the STEM and EXAFS results, theoretical calculation suggest that the distance between Mn and Co of the Mn, Co−N6 model is 2.3 Å, which is in accord with the measured space (Fig. 3b)69. We emphasize that the optimal use of XAS for characterizing dual-active-center catalysts is most effective when dinuclear sites are predominant.

It is important to note that XAS provides sample-averaged information, and contributions from other species, such as single atoms and clusters, need to be carefully considered. Therefore, integrating XAS with other characterization methods, such as TEM/STEM and DFT, is crucial for accurately determining the structure of dual-active-center catalysts.

Chemical states

The combined use of STEM and XAS techniques enables structural visualization of paired active sites and their surrounding environment, while XPS and XANES offer insights into the chemical state and electronic interactions of dual-active-center catalysts. XPS was conducted to examine the chemical composition of the MnCo N-doped carbon catalyst. As shown in Fig. 3c, after Mn/Co introduction, the content of pyridinic N (398.4 eV) decreases compared to N-doped carbon, and a new N species emerges at 399.0 eV, corresponding to the metal-N bond. This transformation of N species indicates the formation of atomically dispersed metal-nitrogen complexes associated with pyridinic N. Additionally, Fig. 3d shows that the Mn K-edge XANES spectra for Mn N-doped carbon fall between MnO and Mn₂O₃, suggesting a Mn valence state between +2 and +3. Together, these techniques provide a comprehensive understanding of the structural, chemical, and electronic properties of dual-active-center catalysts, deepening insights into their performance and interactions.

Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) can be utilized to analyze the chemical states of dual-active-center catalysts, providing complementary insights into their structure and reactivity. FTIR spectroscopy is effective in identifying functional groups within the catalysts by measuring infrared light absorption at specific wavelengths, revealing chemical bonds and molecular vibrations such as C–N, N–H, and C=O stretching modes. The presence of characteristic absorption bands in FTIR spectra, for instance, can signal the formation of metal-nitrogen (M–N) or metal-oxygen (M–O) bonds upon metal incorporation. By examining these spectral features, researchers can better understand the coordination environment of active sites and the interactions between metal centers and the carbon matrix, both crucial for optimizing catalytic performance. Conversely, EPR spectroscopy excels at probing the electronic states of species with unpaired electrons, such as transition metal ions or radical intermediates formed during catalytic reactions. EPR provides details on the electronic structure, oxidation states, and local symmetry of metal centers within dual-active-center catalysts. For example, EPR can detect signals corresponding to different oxidation states of manganese or cobalt, offering insights into their electronic configurations and the stability of reactive species. Additionally, analyzing EPR spectra can illuminate the dynamics of radical intermediates in catalytic processes, essential for understanding reaction mechanisms and improving catalyst efficiency.

For co-catalysts featuring dual active centers of metal clusters or non-metal elements, the analytical approach for metal clusters aligns with that of SACs, as both require precise determination of metal species distribution, coordination environments, and oxidation states to elucidate structure-activity relationships. However, unlike SAC catalysts, metal clusters involve more complex metal-metal interactions, which are further characterized using high-resolution STEM and XAS to confirm the exact structure and electronic states of the clusters. For non-metal dual active centers, where distinct metal signals are absent, techniques such as XPS, Raman, and FTIR are employed to analyze structural and chemical states. These methods allow identification of functional group characteristics, bonding states, and interactions of carbon-based or other non-metal active centers with additional components. For example, XPS assesses bonding states and electron density distributions of non-metal elements, while Raman spectroscopy provides insights into defect structures and the degree of graphitization in carbon-based materials, offering critical information on the reaction mechanisms of non-metal catalysts. Combining these characterization techniques enables a comprehensive understanding of the structure-reactivity relationship in dual-active-center co-catalysts.

Co-catalysis in electro-Fenton process

The EF method is widely utilized in AOPs due to its environmental friendliness, cost-effectiveness, and ease of operation71,72,73. The principle of EF involves the synthesis of H2O2 from O2 at the cathode, which can further be activated to generate •OH74,75. Co-catalytic dual-active-center catalysts can enhance the EF process by improving the adsorption and binding energy of 2e⁻ ORR and 1e⁻ Fenton intermediates through their synergistic interactions.

For SACs in EF processes, the primary co-catalytic approach involves using active center A1 to regulate the electronic distribution of active center A2, thereby altering the adsorption and binding energy of 2e⁻ ORR or 1e⁻ Fenton intermediates on A2. For instance, Cao et al. developed a C3−Fe−Cl2 SACs, and DFT calculations revealed that the H2O2 molecule can be effectively activated into adsorbed •OH at the C3−Fe−Cl2 active site with an exothermic energy of −1.38 eV (Fig. 4a)13. It was observed that the activation of H2O2 to •OH is more facile when the two oxygen atoms of H2O2 interact with both Fe and para-positioned carbon atoms, compared to other configurations. This co-catalytic strategy effectively activates H2O2, leading to the cleavage of peroxide bonds.

a Co-catalysis with SACs13. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society. b, c Co-catalysis with DACs29,60. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society. Copyright 2024 Elsevier B.V. d Co-catalysis with metal cluster catalysts63. Copyright 2023 National Academy of Science, USA. e, f Co-catalysis with nonmetal catalysts67,76. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society. Copyright 2022 Elsevier B.V. g Four co-catalysis mechanisms in the EF process. The pink spheres represent oxygen atoms, the white spheres represent hydrogen atoms, the dark gray elliptical spheres represent pollutants (ECs), and the black solid line represent electron transfer pathway.

To better facilitate the tandem coupling of the 2e⁻ ORR and the 1e⁻ Fenton process, establishing dual-active-center catalysts for both the 2e⁻ ORR and 1e⁻ Fenton processes is crucial, with DACs emerging as optimal candidates. Qin et al. developed CoFe DACs where CoN4 sites facilitate the adsorption of *OOH to synthesize H2O2, while FeN4 sites are responsible for the activation of H2O2 (Fig. 4b)29. Similarly, Sun et al. optimized the coordination of N in CoFe DACs by adjusting the calcination temperature to produce distinct structures featuring pyrrolic CoN4 and pyridinic FeN4 (Fig. 4c)60. DFT calculations confirmed that pyrrolic CoN4 sites are conducive to the formation of H2O2 from *OOH, while H2O2 is readily activated at pyridinic FeN4 sites to generate •OH. This co-catalytic approach enhances the number of active sites for H2O2 generation and activation, but it is crucial to screen the selectivity of metal centers for 1e−, 2e−, 3e−, and 4e− ORR processes when selecting metal active centers. In addition to DACs, metal clusters can also achieve the 3e⁻ process (2e⁻ ORR + 1e⁻ Fenton). Dong et al. developed a dual-functional Mo–Fe cluster-based EF catalyst (Fig. 4d)63. This catalyst demonstrated exceptional catalytic activity for the three-electron-dominated oxygen reduction reaction in sodium sulfate, resulting in a highly efficient EF reaction with a low overpotential for the removal of organic contaminants from wastewater. DFT analysis revealed that the dual-functional MoFe/C3N5 catalyst facilitated a synergistic effect of the Mo–Fe dual single-atom centers, which altered the adsorption/dissociation behavior and reduced the overall reaction barriers, thereby enhancing organic oxidation during the EF process. Additionally, Xiao et al. reported a catalyst capable of selectively electrochemical reduction of O2 to •OH via a three-electron pathway with FeCo clusters encapsulated by carbon aerogel52. The graphite shell with exposed -COOH groups promotes the two-electron reduction pathway for H2O2 generation, which is then stepped by a one-electron reduction towards •OH. The electrocatalytic activity can be tuned by adjusting the local electronic environment of the carbon shell with electrons derived from the inner FeCo clusters. This co-catalytic approach allows direct three-electron ORR at individual active sites through the electronic interactions between the clusters and other active centers.

In the pursuit of metal-free catalysts for EF systems aimed at electro-generation and activation of H2O2, several researchers have focused on the catalytic potential of nitrogen-doped carbonaceous materials for decomposing H2O2 into •OH. Zhang et al. prepared a metal-free EF catalyst by pyrolyzing coffee residues to create a nitrogen self-doped biochar air-cathode (Fig. 4e)67. During pyrolysis, endogenous nitrogen transitioned from edge-doping to graphitic-doping, and N vacancies began to form when the peak temperature exceeded 700 °C. Structural characterization and DFT calculations indicated that graphitic N was a critical site for H2O2 generation, and both graphitic and pyridinic N were active sites for H2O2 activation to •OH. Graphitic N and N vacancies, with their stronger capabilities in O2 adsorption and electron trapping, were proposed as the electroactive sites for 1O2 and •O2− formation. Utilizing different nitrogen electronegativities for co-catalysis can avoid the introduction of metals. However, precise control of the catalyst’s calcination temperature is crucial, as variations directly affect the types and quantities of nitrogen species present. Furthermore, Liu et al. developed a metal-free EF system using nitrogen-doped activated carbon modified graphite felt (NACs/GF) for degrading sulfamethazine through self-generation and utilization of H2O2 (Fig. 4f)76. As the activation temperature increased from 700 to 1100 °C, graphitic nitrogen became predominant, and its neighboring pyridinic nitrogen formed N vacancies. The NAC-1100/GF EF system exhibited high H2O2 selectivity (94.3%) and excellent H2O2 yield (44.6 mg/L). The *OOH intermediate, which is the main barrier in the 2e− ORR process, was formed and desorbed at the graphitic N sites, while the N vacancies enhanced electron transfer with *O2 and *OOH to accelerate H2O2 generation. Graphitic N and pyrrolic N adsorbed sulfamethazine via van der Waals forces, while pyridinic N interacted with H2O2 through hydrogen bonding, establishing a controlled reaction zone near the cathode. The highly electronegative pyridinic N provided electrons for catalyzing the formation of •OH from H2O2, while N vacancies generated more unpaired electrons to facilitate the formation of 1O2. Finally, we compared and summarized the catalytic performance of the above catalysts in the EF system in Table 2.

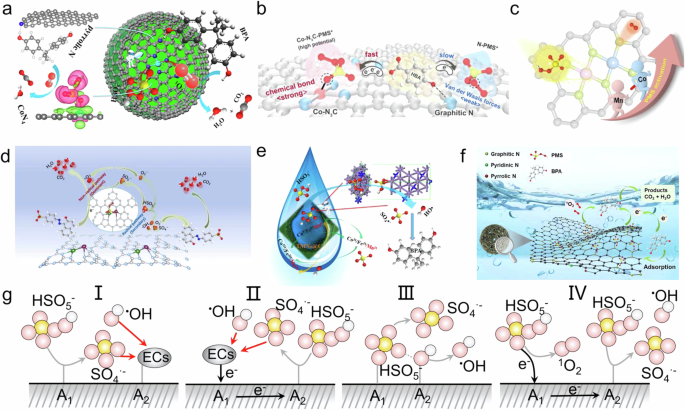

In summary, we propose that there are four potential co-catalytic mechanisms for dual-active-center catalysts in the EF system (Fig. 4g): 1) Active site A1 enhances H2O2 generation, while active site A2 is responsible for activating H2O2; 2) Active site A2 influences the electron distribution of A1, thereby regulating A1 H2O2 synthesis; 3) Active site A1 impacts the electron distribution of A2, thereby modulating A2 H2O2 activation. 4) Active site A1 activates H2O2, while active site A2 adsorbs pollutants.

Co-catalysis in Photo-Fenton/Photo-Fenton-like process

Photo-Fenton/photo-Fenton-like process is a promising method to achieve chemical transformation by harnessing solar energy, which involves three consecutive steps: 1) the adsorption of the reactants, 2) the charge generation and transfer for ROS generation, and 3) the surface reaction and product desorption77,78,79. The co-catalytic of dual-active-center catalysts can be effectively integrated into these three processes.

OV have been confirmed by several studies to effectively enhance the adsorption of hydroxyl groups, which in turn facilitates the subsequent surface reaction of phenol oxidation80,81. Furthermore, in the context of ROS generation, single-atom metals are recognized as efficient active sites in both Fenton-catalytic and photocatalytic ROS production, due to their metal centers high electron density. Single-atom dual-active-center catalysts can realize the co-catalytic effect of OV and ROS. For instance, Yang et al. reported a highly efficient Fe/TiO2-OV SACs, which demonstrated a synergistic effect in the photo-Fenton mineralization of phenol56. In this system, oxygen vacancies significantly accelerate the separation of photogenerated charges and direct their transfer to Fe single atoms, enabling rapid ROS generation while also promoting the selective adsorption and activation of phenol. This synergistic catalysis between Fe single atoms and oxygen vacancies results in a high reactivity for phenol photo-Fenton mineralization, surpassing the performance of most reported transition-metal-based catalysts. Additionally, Qian et al. constructed an innovative heterojunction between Co–CN SACs and g-C3N4 for heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like reactions (Fig. 5a)82. The built-in electric field across the heterojunction promotes the separation and migration of photogenerated charge carriers, facilitating rapid electron transfer from g-C3N4 to Co–CN SACs. Theoretical calculations and transient absorption spectroscopy revealed that this modulated charge transfer and trapping in the SA–Co–CN/g-C3N4 heterostructure significantly enhances ROS generation via PMS activation under light irradiation.

a Co-catalysis with SACs82. Copyright 2023 John Wiley & Sons. b Co-catalysis with DACs61. Copyright 2024 John Wiley & Sons. c, d Co-catalysis with metal cluster catalysts45,83. Copyright 2023 John Wiley & Sons. Copyright 2023 National Academy of Science, USA. e Co-catalysis with nonmetal catalysts54. Copyright 2023 Elsevier B.V. f Four co-catalysis mechanisms in the photo-Fenton/photo-Fenton-like process. The pink spheres represent oxygen atoms, the white spheres represent hydrogen atoms, the yellow spheres represent sulfur atoms, the dark gray elliptical spheres represent pollutants (ECs), the black solid line represent electron transfer pathway, and the sunlight represents the light for photocatalysis.

Dual-atom metal dual-active-center catalysts have been a major focus in the study of photo-Fenton/photo-Fenton-like catalysts. These catalysts utilize independent dual-active metal centers to enhance photogenerated charge transfer and redox processes separately. Recently, Lian et al. synthesized atomically dispersed AgCo doped in g-C3N4 as a typical model to investigate the proposed photo-Fenton reaction for the degradation of various pollutants, leveraging the synergistic effects of efficient photogenerated charge transfer and redox-active sites (Fig. 5b)61. Theoretical calculations and experimental measurements confirmed that the single-atom Ag acts as a reservoir for photoinduced electrons, while Co serves as the Fenton redox center. In designing dual-active-center co-catalysts for photo-Fenton and photo-Fenton-like reactions, it is crucial to select an active site A1 with strong photogenerated charge transfer capabilities, while site A2 should possess elements with high selectivity for Fenton-driven ROS generation. Furthermore, optimizing the distance between A1 and A2 is another key challenge, as this is an inherent issue in all dual-metal SACs.

To be applied in photo-Fenton/photo-Fenton-like processes, metal clusters must be combined with materials capable of semiconductor behavior. For example, Tang et al. constructed 0D/3D Cu-FeOOH/TCN composites as photo-Fenton catalysts by assembling amorphous Cu-FeOOH clusters onto 3D double-shelled porous tubular g-C3N4 (TCN), synthesized through one-step calcination (Fig. 5c)83. DFT calculations demonstrated that the synergistic effect between Cu and Fe species facilitates both the adsorption and activation of H2O2, as well as the efficient separation and transfer of photogenerated charges. Moreover, Mo et al. designed TiO2@Fe species-N-C catalysts with Fe atomic clusters and satellite Fe–N4 active sites to initiate the PMS oxidation reaction (Fig. 5d)45. The charge redistribution induced by the clusters was verified, enhancing the interaction between the single atom and PMS. Specifically, the incorporation of clusters optimized the HSO5− oxidation and SO5•− desorption steps, accelerating the overall reaction process. Characterization of the reaction mechanism suggested that PMS, acting as an electron donor, transfers electrons to Fe species within the TiFe clusters, leading to the generation of 1O2. Subsequently, hVB+ induces the formation of electron-deficient Fe species, thereby promoting the reaction cycle.

Nonmetal dual-active-center photo-Fenton/photo-Fenton-like catalysts are generally based on modified g-C3N4. g-C3N4 is a low-cost organic semiconductor that has been widely used for photocatalytic H2O2 generation and photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants due to its suitable band structure, specific photo response properties, good stability, and ease of modification. For instance, Jing et al. developed a novel photocatalysis-self-Fenton system based on a coral-like B-doped g-C3N4 photocatalyst for the removal of 4-chlorophenol (4-CP) (Fig. 5e)54. In this system, H2O2 is generated in situ through photocatalysis on B-doped g-C3N4, while the cycling of Fe2+/Fe3+ is accelerated by photoelectrons, and photogenerated holes promote the mineralization of 4-CP. The effective combination of these processes enhances charge separation and mass transfer between phases, leading to efficient in-situ H2O2 production, faster Fe2+/Fe3+ cycling, and improved hole oxidation. The catalytic performance of the above catalysts in the photo-based system are summarized in Table 3.

In summary, we propose four potential co-catalytic mechanisms for dual-active-center catalysts in the photo-Fenton/photo-Fenton-like system (Fig. 5f): 1) Active site A1 generates h+ to directly oxidize pollutants, while photogenerated electrons are transferred to active site A2 to activate H2O2; 2) Active site A1 produces h+ to directly oxidize pollutants, and photogenerated electrons are transferred to active site A2 to synthesize H2O2; 3) Active site A1 generates h+ to produce H2O2 from H2O, while the subsequent photogenerated electrons activate the H2O2, and additional photogenerated electrons at active site A2 contribute to the formation of O2•− from O2; 4) Active site A1 generates h+ to convert HSO5− to •SO4−, and subsequently, photogenerated electrons at active site A2, along with h+, convert O2 to 1O2.

Co-catalysis in PMS Fenton-like process

PMS Fenton-like systems have been demonstrated as powerful techniques for generating various ROS, such as •OH, SO4•–, O2•–, and nonradical species84,85,86,87. These active species can be produced through the reduction (PMS as electron accepter) and oxidation (PMS as electron donor) processes of PMS85,86. Consequently, dual-active-center catalysts can exhibit various co-catalytic behaviors during the generation of ROS from PMS Fenton-like processes for pollutant degradation. The following sections will discuss different co-catalytic mechanisms associated with various types of dual-active-center catalysts.

In the PMS Fenton-like process, SACs typically co-catalyze PMS in conjunction with the supporting nitrogen atoms. Li et al. demonstrate that single cobalt atoms anchored on porous N-doped graphene, featuring dual reaction sites, act as highly reactive and stable Fenton-like catalysts for the efficient catalytic oxidation of recalcitrant organics through the activation of PMS (Fig. 6a)43. DFT calculations reveal that the CoN4 site, with a single Co atom, serves as the active site with optimal binding energy for PMS activation, while the adjacent pyrrolic N site adsorbs organic molecules. The presence of dual reaction sites significantly reduces the migration distance of the active 1O2 produced from PMS activation, thereby enhancing the Fenton-like catalytic performance. Additionally, Zhu et al. report the preparation of carbon-supported cobalt-anchored single-atom catalysts with controlled Co−N sites and free functional N species (Fig. 6b)16. They systematically investigate the roles of metal- and non-metal-bonded functionalities in SACs for PMS-driven Fenton-like reactions, revealing their contributions to performance enhancement and pathway steering. Experiments and computations demonstrate that the Co−N3C coordination is crucial for forming a surface-confined PMS* complex, which triggers the ETP and promotes reaction kinetics due to the optimized electronic state of Co centers. Meanwhile, the non-metal-coordinated graphitic N sites serve as favorable pollutant adsorption sites and additional PMS activation sites, accelerating electron transfer.

a, b Co-catalysis with SACs16,43. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society. Copyright 2024 John Wiley & Sons. c, d Co-catalysis with DACs69,88. Copyright 2023 Elsevier B.V. Copyright 2024 Elsevier B.V. e Co-catalysis with metal cluster catalysts89. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society. f Co-catalysis with nonmetal catalysts91. Copyright 2024 Elsevier B.V. g Four co-catalysis mechanisms in the PMS Fenton-like process. The pink spheres represent oxygen atoms, the white spheres represent hydrogen atoms, the yellow spheres represent sulfur atoms, the dark gray elliptical spheres represent pollutants (ECs), and the black solid line represent electron transfer pathway.

Dual-atom catalysts have emerged as a research hotspot due to their controllable dual-atom active sites, making them ideal candidates for achieving co-catalysis with PMS Fenton-like dual-active-center catalysts. Wang et al. successfully fabricated Fe−Co DACs with an FeCo−N6 moiety anchored in the carbon skeleton42. This catalyst achieves nearly 100.0% ETP for highly efficient PMS activation by regulating PMS adsorption modes. The Fe−Co dual-site optimizes the adsorption mode of PMS, enhancing electron rearrangement of the adsorbed PMS* complex with weak stretching of the O−O bond. This optimization drives exclusive selectivity for the ETP pathway, as demonstrated through experiments and DFT calculations. Additionally, DACs can achieve precise coordination with PMS through accurate control of inter-atomic distances, facilitating peroxide bond cleavage. Cheng et al. demonstrate that by precisely controlling the Fe1−Fe1 distance to <4 Å, PMS is saturated, while Fe−N−C−PMS* formed on Fe sites with an Fe1–Fe1 distance of 4–5 Å can coordinate with the adjacent FeII−N4, forming an inter-complex that enhances charge transfer to produce FeIV = O25. Furthermore, Yao et al. reported the use of a programmable metal-triazolate framework as a precursor to introduce bimetallic sites (comprising Mn and Co) for the synthesis of contiguous MCNC (Fig. 6c)69. Through a combination of 1O2 quantification, 18O isotope labeling, and theoretical simulations, they revealed that MCNC activates PMS via a unique “relay” mechanism, where one site interacts with the oxygen atom in PMS, while the other accelerates the production of 1O2 through the activation of PMS*. This work advances the fundamental understanding of PMS activation and enhances the removal of refractory pollutants by rationally regulating dual-site synergistic catalysts, thereby deepening the on-demand design of Fenton-like reactions. Additionally, Qin et al. reported a novel dual Fe-Ni atomic catalyst on graphitic carbon nitride with NV sites (Fig. 6d)88. The Nv in FeNi-NV/CN significantly augments the electron density around the Fe-Ni atomic pairs, which enhances the ETP and improves pollutant degradation efficiency. DFT calculations and experimental results for FeNi-NV/CN confirmed the robust synergistic interactions between dual single-atomic reaction sites and NV. Therefore, DACs offer two approaches in the PMS Fenton-like co-catalysis process: 1) optimizing adsorption and activation pathways through dual active sites, and 2) fine-tuning inter-atomic distances to enhance bond cleavage and charge transfer efficiency.

Metal-clusters co-catalyze PMS Fenton-like catalysts by utilizing the valence state cycling of the cluster metals to influence the PMS Fenton-like process. For instance, Li et al. synthesized FexMn6-xCo4−N@C nanodices, which were systematically characterized and functionalized as Fenton-like catalysts for the catalytic oxidation of BPA through PMS activation (Fig. 6e)89. The mechanism of PMS activation is as follows: First, ≡Co0/Fe0/Mn0 in FexMn6-xCo4 − N@C activates PMS to produce SO4•– and •OH radicals while itself being oxidized to ≡Co2+/Fe2+/Mn2+ and ≡Co3+/Fe3+/Mn3+, respectively. Second, the generated ≡Co2+/Fe2+/Mn2+ can be rapidly oxidized by PMS to produce SO4•– radicals. Both PMS and ≡Co0/Fe0/Mn0 further reduce ≡Co3+/Fe3+/Mn3+ back to ≡Co2+/Fe2+/Mn2+, thus allowing the reaction to proceed continuously until PMS is completely consumed. Additionally, the stronger adsorption energy, and greater number of electrons received on PMS catalyzed by Mn4N significantly enhance the catalytic activity of FexMn6-xCo4 − N@C.

1O2 is an excellent ROS for the selective conversion of organic matter, particularly in AOPs. However, due to the significant challenges associated with synthesizing single-site type catalysts, controlling and regulating 1O2 generation in AOPs remains challenging, and the underlying mechanisms are still largely obscure. To address this issue, Weng et al. utilized the well-defined and flexibly tunable sites of covalent organic frameworks (COFs)90. They achieved precise regulation of ROS generation in PMS-based AOPs through site engineering of COFs. Notably, COFs with bipyridine units (BPY-COFs) facilitate PMS activation via a nonradical pathway, resulting in 100.0% 1O2 production. In contrast, biphenyl-based COFs with nearly identical structures activate PMS to produce radicals (•OH and SO4•⁻). The authors demonstrate that COFs achieve C−H and N coordination with PMS to cleave the O–O bond, followed by C−C sites in the COFs adsorbing O₂ to generate 1O2. Furthermore, Di et al. designed an in-situ nitrogen-doped hollow carbon catalyst (DNC-9), which balances efficient catalytic performance with metal-free catalysis (Fig. 6f)91. Graphitic nitrogen in DNC-9 plays a crucial role in this activation by providing adsorption sites that facilitate the decomposition of PMS and the generation of 1O2. Additionally, graphitic nitrogen forms a transient active intermediate, DNC-9-PMS*, which enhances the degradation of bisphenol A. This non-metallic co-catalytic approach has the following advantages: it enhances selectivity and efficiency in generating 1O2, which can lead to more effective and controlled oxidation processes compared to conventional radical-based systems. Table 4 showcases the catalytic performances of the above catalysts in PMS-based systems.

In summary, we have outlined several potential co-catalytic mechanisms for PMS Fenton-like dual-active-center catalysts (Fig. 6g): 1) Active site A1 adsorbs PMS, transforming it into SO4•⁻ and •OH, while active site A2 adsorbs pollutants; 2) Pollutants transfer electrons to active site A1 via an ETP, and active site A1 then transfers electrons to A2, facilitating the activation of PMS at site A2; 3) Active sites A1 and A2, positioned at specific distances, cleave the peroxide bond in PMS, generating SO4•⁻ and •OH; 4) PMS, acting as an electron donor, transfers electrons to active site A1, converting PMS into 1O2, while A1 then transfers electrons to active site A2 for further PMS activation.

Co-catalysis in PED-based Fenton-like systems

H2O2 and O2 can be efficiently reduced to ROS at electron-rich centers, while pollutants are captured and oxidized at electron-deficient sites92,93,94. Electrons derived from the pollutants are transferred to the electron-rich centers via bonding bridges95,96,97. This process surpasses the classic Fenton mechanism, significantly enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of pollutant removal across a wide pH range. Therefore, we provide a comprehensive overview of co-catalysis, where pollutants act as the electron donor in Fenton-like systems, detailing their performance in pollutant degradation and interfacial reaction processes.

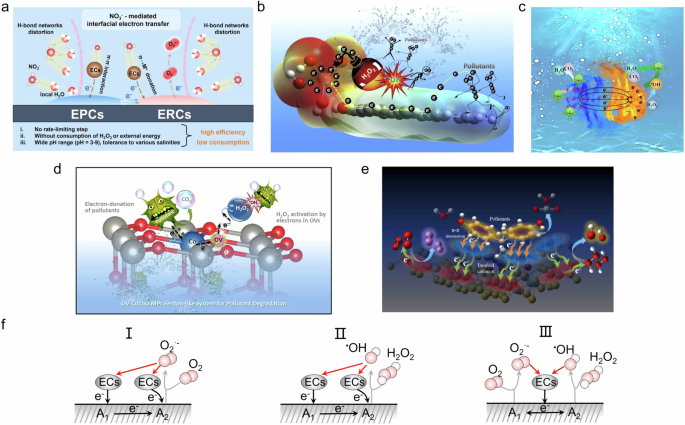

For SACs in Fenton-like processes where pollutants are the electron donor, the primary co-catalytic mechanism involves using active center A1 to obtain electrons from pollutants, which are subsequently transferred to active center A2 to generate ROS via the Fenton process. Cao et al. designed Fe SACs anchored on aromatic carbon (π) framework composites, which feature reinforced cation–π structures and were successfully synthesized through a cascaded self-assembly and thermal treatment process46. It was observed that the local bond networks of H2O molecules on the surface structure can be distorted by salinity anions, facilitating the preferential adsorption of ECs and strengthening the orbital interactions (π→cation donation) between ECs and surface electron-rich centers through intermolecular forces (Fig. 7a). Moreover, Lyu et al. reported that Cu single-atom catalysts demonstrate high activity and efficiency in removing refractory organic compounds with H₂O₂ (Fig. 7b)98. Characterization reveals that nanoscale Cu(0) and Cu(II) form on the rGO surface during annealing, accompanied by C–O–Cu bond formation between the rGO substrate and Cu(II) species in the nZVC-Cu(II)-rGO structure. This bonding induces cation–π interactions on the surface, resulting in reinforced electron-rich micro-centers around the nZVC-enhanced Cu(II) species and electron-poor micro-centers on the rGO aromatic rings. The generation of nanoscale Cu(0) further polarizes these dual reaction micro-centers, significantly accelerating electron transfer within the system and enhancing H₂O₂ reduction to •OH radicals at the electron-rich micro-centers. Meanwhile, Liao et al. reported a novel Fenton-like metal-cluster catalyst Cu-PAN3 (Fig. 7c)66. Their research demonstrated that the dual-active centers consist of Cu–N–C and Cu–O–C bridges between copper and graphene-like carbon, forming electron-poor/rich centers on the catalyst surface. H2O2 is primarily reduced at electron-rich Cu centers to generate radicals for pollutant degradation, while pollutants are oxidized by donating electrons to the electron-poor C centers. This electron transfer mechanism helps prevent the ineffective decomposition of H2O2 at the electron-poor sites. Zhan et al. reported the surface OV as the electron temporary residences to construct a dual-active-center Fenton-like catalyst with abundant surface electron-rich/poor areas consisting of OV-rich Co-ZnO microparticles (Fig. 7d)95. The lattice-doping of Co into ZnO wurtzite results in the formation of OV with unpaired electrons (OV) and electron-deficient Co3+ sites according to the structural and electronic characterizations. Both experimental and theoretical calculations prove that the electron-rich OV are responsible for the capture and reduction of H2O2 to generate hydroxyl radicals, which quickly degrades pollutants, while a large amount of pollutants are adsorbed at the electron-deficient Co3+ sites and act as electron donors for the system, accompanied by their own oxidative degradation. Additionally, Lyu et al. reported a honeycomb microsphere-like MoS2 cross-linked g-C3N4 hybrid metal-cluster catalyst (Fig. 7e)53. Using a combination of advanced characterization techniques and theoretical calculations, they revealed the presence of twofold cation–π interactions (Mo–O–C and Mo–S–C bonding bridges). These interactions enable pollutants to transfer electrons to H2O2 and O2, effectively inhibiting the oxidative decomposition of H2O2 and promoting its hydroxylation during the Fenton-like reaction. Therefore, these studies demonstrate that Fenton-like processes in SACs and metal-cluster catalysts are primarily driven by the electron transfer between pollutants and active centers. The interaction between electron-rich and electron-poor sites enables the efficient generation of ROS, while the incorporation of cation–π structures and dual-active centers further enhances the catalytic performance. By facilitating the selective transfer of electrons and preventing the premature decomposition of H2O2, these systems offer a more sustainable and effective approach for pollutant degradation, even under complex environmental conditions such as high salinity. The catalytic performances of the above catalysts in the PED-based system are summarized in Table 5.

a, b Co-catalysis with SACs46,98. Copyright 2023 National Academy of Science, USA. c, d, e Co-catalysis with metal cluster catalysts53,66,95. Copyright 2024 Elsevier B.V. Copyright 2023 Elsevier B.V. f Three co-catalysis mechanisms in PED-based Fenton-like processes. The pink spheres represent oxygen atoms, the white spheres represent hydrogen atoms, the yellow spheres represent sulfur atoms, the dark gray elliptical spheres represent pollutants (ECs), and the black solid line represent electron transfer pathway.

In summary, we have outlined three potential co-catalytic mechanisms for PED-based Fenton-like processes involving dual-active-center catalysts (Fig. 7f): 1) Active site A1 receives electrons from the pollutant and transfers them to active site A2. Meanwhile, active site A2 can function both as an electron acceptor to receive electrons from pollutants and as an electron donor for O2 reduction; 2) Similar to the 1) mechanism, active site A2 acts as an electron donor to activate H2O2; 3) Pollutants act as electron donors to the catalyst support, which transfers electrons to active sites A1 and A2, where A1 reduces O2 to 1O2 and A2 activates H2O2 to produce •OH, with both 1O2 and •OH attacking the pollutants.

Effects of distance on dual-active-center catalysts

The ultimate goal in designing co-catalytic dual-active-center catalysts is to precisely control the spatial arrangement of active centers, thus achieving optimal catalytic performance by leveraging synergistic effects between these centers99. This intricate design demands a thorough understanding of the role that the inter-site distance plays in governing catalytic activity. These interactions can be broadly classified based on distance: (a) short-range interactions, typically confined to sub-nanometer scales, where strong covalent or metallic bonding between neighboring atoms or ions dominates; and (b) long-range interactions, which extend to nanometer scales and involve weaker forces such as van der Waals interactions, electrostatic attraction, or dipole-dipole interactions99.

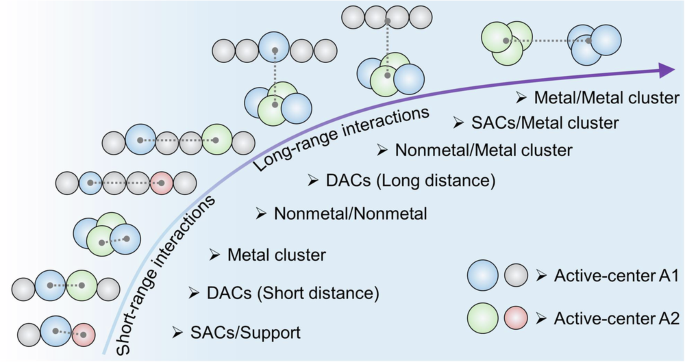

As shown in Fig. 8, short-range interactions are mainly observed in SACs, where co-catalysis occurs between heteroatoms, such as metal-nonmetal (M–N) or metal-carbon (M–C) bonds. Similarly, in DACs or metal clusters, dual-active centers play a key role in modulating the electronic environment, influencing electron density redistribution and adjusting the adsorption energy of reaction intermediates through orbital hybridization. The spatial arrangement of these active centers can also significantly affect transition state stability, thereby impacting reaction kinetics and overall catalytic efficiency. In contrast, long-range interactions are more common in systems involving nonmetal/nonmetal, DACs, nonmetal/metal clusters, SACs/metal clusters, or metal/metal clusters in AOPs. These extended interactions can govern overall catalytic efficiency by affecting diffusion-limited mass transfer or charge separation over larger distances, both critical for maintaining high catalytic turnover rates and enhanced pollutant degradation. Maintaining an optimal inter-site distance is essential: excessively close spacing may cause detrimental charge delocalization, while overly distant centers weaken co-catalytic synergy, reducing selectivity of active sites for intermediates or pollutant molecules. Balancing proximity and electronic coupling is crucial to maximizing electron transfer efficiency and increasing the rate of desired reactions. Thus, precise spatial control is vital for optimizing reaction pathways toward desired outcomes, such as ROS generation or pollutant adsorption.

The blue sphere and gray sphere represent active site A1, while the green sphere and pink sphere represent active site A2. The gray dashed lines represent the specific positions and distances of the active sites.

Beyond inter-site distance, the atomic density of active sites is equally significant in co-catalytic SACs/DACs systems100,101. A higher density reduces the average distance between adjacent sites, fostering cooperative effects such as increased electron exchange and enhanced localized adsorption of reactive species. This greater density also promotes synergistic interactions among active centers, collectively boosting catalytic activity. Thus, manipulating atomic density effectively regulates inter-site distances, thereby enhancing overall catalytic performance. Future research should prioritize refining synthesis methodologies—such as atomic layer deposition, solvothermal methods, and templating techniques—to achieve precise control over site density and spatial distribution. The development of advanced characterization tools, including HAADF-STEM and XRD, will be essential for elucidating the atomic-scale arrangement and electronic properties of active centers. Additionally, exploring innovative catalyst supports, such as nanocrystals, metal oxides, MXenes, and transition metal dichalcogenides, which can accommodate varying densities and promote electron transfer, will be pivotal in advancing dual-active-center catalyst design102,103,104,105.

Conclusions and outlook

In conclusion, this review has thoroughly summarized the synthesis strategies and advanced characterization techniques developed for co-catalytic dual-active-center catalysts in AOPs systems. These catalysts, employed in EF, photocatalytic, PMS-, and PED-based -based Fenton-like systems, demonstrate diverse co-catalytic interactions that significantly enhance their performance. We have provided detailed mechanistic insights into these interactions, emphasizing how they influence the generation of ROS and pollutant degradation pathways under various conditions. A key takeaway from our analysis is the importance of controlling short-range and long-range interactions, as well as optimizing the atomic density of active sites. These factors fundamentally affect the charge distribution and adsorption energy, thereby guiding the design of high-performance SACs/DACs co-catalysts. By offering a fresh perspective on these design principles, this review aims to inspire new directions in catalyst development.

Moving forward, a profound comprehension of the electronic interactions between dual-active centers, which dictate catalytic efficiency, is imperative for the rational design of catalysts tailored to specific reactions. To accomplish this, innovative synthesis techniques that enable precise control over the spatial arrangement and inter-site distances of active centers are essential. Furthermore, the progression of characterization technologies, particularly in situ and operando techniques, is anticipated to elevate our capability to monitor catalyst behavior with unparalleled resolution and speed, providing real-time insights into their operational mechanisms. Another limitation lies in the scalability of these precise synthesis methods, as many laboratory techniques are difficult and costly to translate to an industrial scale. Additionally, the integration of machine learning techniques into catalyst design and optimization presents a promising avenue. By utilizing extensive datasets and predictive algorithms, researchers can pinpoint optimal configurations of dual-active centers and predict their performance under various reaction conditions. Moreover, the application of machine learning to the study of dual-active-center co-catalysts has the potential to further unravel the intricate relationships between structure and function, thereby enhancing our understanding of co-catalysis in complex systems. Finally, achieving cost-effectiveness without sacrificing performance remains an ongoing challenge, especially for applications requiring large quantities of catalysts. Scaling up the precise engineering of dual-active-center catalysts to industrial levels is a significant frontier to address. Dual-active-center catalysts show remarkable versatility by adapting to various pollutant profiles and operational parameters, making them well-suited for extensive use in environmental remediation. Notably, they exhibit strong catalytic performance in complex matrices where multiple pollutants coexist, enabling selective ROS generation and pollutant adsorption, both of which are essential for maximizing contaminant removal efficiency in real-world water treatment. The creation of scalable and economically viable synthesis methodologies is crucial for bridging the gap between laboratory-scale innovations and practical applications in AOPs technologies. Achieving this will pave the way for commercial-scale production and implementation, allowing these advanced catalysts to reach their full potential in real-world applications.

Responses