Sleep and diurnal alternative polyadenylation sites associated with human APA-linked brain disorders

Introduction

Dysregulation of sleep and circadian rhythms can profoundly impact human health and compound disease1,2. Indeed, sleep disruption is associated with negative outcomes in cardiovascular, metabolic, immunologic, and cognitive health that can have substantial short- and long-term consequences3. Alterations in sleep and circadian rhythms are often observed with various brain disorders, including autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, major depression, schizophrenia, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s diseases4,5,6,7. Complicating the association between sleep and health is the fact that functional aspects of sleep remain largely undefined and inconclusive8,9; however, the use of evolutionarily distinct animal models to study sleep has historically offered keen insights10,11. For example, studies on circadian- and sleep-dependent gene-regulatory mechanisms in diverse species, including flies, rodents, and humans, have identified important phylogenetically conserved pathways with functional relevance12,13,14,15. Employing unbiased approaches, such as large-scale metabolomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses, have also greatly aided in the generation of conceptual frameworks for characterizing sleep function in health14,16. Therefore, performing such discovery-based studies of sleep and circadian regulatory processes in model organisms will help define the fundamental biological mechanisms underlying sleep function and inform preclinical relevance for comorbidities of sleep dysfunction associated with poor health.

Alternative polyadenylation (APA) site usage is an important and often overlooked mechanism of gene regulation, that can affect mRNA stability, mRNA/protein targeting, translational competence, and generate alternative protein isoforms17,18. APA sites are common and occur most frequently in the 3′ untranslated regions (3′ UTR) of mRNAs across phylogeny, with more than half of human genes having multiple polyadenylation sites (PASs) that generate alternative isoforms19. These isoforms can have altered coding sequences or 3′ UTRs, resulting in the diversification of cis-regulatory elements (e.g., RNA-binding protein sites, microRNA binding sites) that influence transcript abundance, trafficking, stability, and/or translation efficiency20. Furthermore, there’s growing evidence of cell-type-specific APA preference21. The involvement of APA in the context of sleep and circadian rhythms has been largely unexplored, with the few studies available mostly focused on peripheral organs22,23 and cells24. Here, we have characterized how APA site usage oscillates based on the time-of-day as well as how it is altered following acute changes in sleep pressure, specifically in the adult mammalian brain. Multiple methodologies have been developed for transcriptome-wide profiling and mapping of APA sites25,26. To complete this study, we performed whole transcriptome termini sequencing (WTTS-seq)27,28 analysis to profile the variations in APA usage that occur due to sleep pressure and daily rhythms in the rat forebrain. Over 31,000 PASs were recovered in total, with 45% of the represented genes having multiple APA sites. Interestingly, many of the PASs sequenced were not previously annotated in the rat genome. Moreover, a total of 2011, (6%) of PASs cycled over the day, and 831 (3%) were homeostatically regulated following sleep loss following sleep loss or during recovery. Over half of all cycling or differentially expressed PASs were APAs, (i.e., in genes with ≥2 PASs). Given the importance of sleep4,5,6,7 and APA in health and disease25,29,30, we compared our sequencing results with results from a recent study that determined APA usage in human brain disorder susceptibility31. The genes found in both studies warrant further examination and could lead to new preclinical animal models to investigate these disorders.

To the best of our knowledge, the current study represents the first comprehensive, transcriptome-wide mapping of APA sites in adult mammalian brain tissue over the day-night cycle as well as following changes in sleep homeostasis. This global temporal dataset will be useful for future comparative studies that require the determination of baseline APA site usage profiles in the mammalian brain. Furthermore, our study underscores the importance of using alternative-omic approaches to characterize phylogenetically conserved genome-phenome information and reveals another expansive layer of complexity in sleep and circadian gene regulation that has not previously been documented.

Results

Identification of PASs in the rat forebrain

Given the rat transcriptome is not as extensively annotated as the human or mouse, we first identified all PASs, including novel candidate PASs prior to determining changes in PAS usage. Replicate diurnal (central forebrains) were taken from five rats every four hours starting at two hours after lights on (i.e., ZT2, ZT6, ZT10, ZT14, ZT18 and ZT22) (Fig. 1A, B). RNA was purified from these samples and used to generate WTTS-seq cDNA libraries that were subsequently sequenced. Poly(A)-directed sequence reads were then mapped to the rat genome, giving rise to 31,757 PAS clusters (see Supplementary Table S1). Among the 31,757 PAS clusters identified, a sizable portion mapped to novel unannotated PASs, leaving 26,635 PASs that mapped to named loci (i.e., genes). Many APAs occur at different points within the longest 3′ UTR (Fig. 1C, sites 4 and 5). Some are distal to the longest documented 3′ UTR (site 6), while some occur in internal exons (site 1) or introns (sites 2 and 3) (Fig. 1C). In our dataset of all PASs that mapped to genes, 45% mapped to genes with ≥2 APA sites, and 19% mapped to genes with ≥3 APA sites (Fig. 1D).

A The region of the central rat forebrain that was collected and used for RNA extraction is bounded by dotted lines and labeled ‘forebrain’ (brain illustration was generated by modifying an image obtained in Motifolio (Motifolio Inc., Ellicott City, MD, USA). B For sleep homeostasis experiments, rats were sleep-deprived for 6 h and allowed to recover for 0–8 h before tissue extraction. Three of the time-matched controls (no SD) were shared with the diurnal experiment and one additional time point (no SD at ZT8), was not in common. For the diurnal analysis, samples were taken at 4 h intervals from ZT2 until ZT22. Five biological replicates were used for all data points. C A diagram of a generic gene shows different types of APAs: within an internal exon (1); within an early intron (2); following an internal exon (3); within the longest documented 3′ UTR (4); at the terminus of the longest documented 3′ UTR (5); and distal to longest documented 3′ UTR. D WTTS-seq PAS results; the number of genes on the x-axis (log10 scale) are plotted against the number of APA sites per gene.

Identification of PASs that exhibit a daily cycle

Periodicity of PAS expression was assessed using meta2d32. Diurnal (24 h period) oscillations were demonstrated for 2011 PASs. Among these, 1173 were in genes with ≥2 total APA sites, including ones in known diurnal transcripts, such as Dbp (diurnal in 2 of 2 APA sites recovered), Nr1d2 (in 1 of 1), Per2 (in 2 of 2), and Ntrk2 (in 2 of 10)33 (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2).

To look for functions or cell components that are particularly affected by APA site usage in a time-of-day dependent manner, we performed pathway and gene ontology (GO) over-representation analyses using the online tool WebGestalt34. The set of 1173 gene symbols corresponding to diurnal PASs in genes with ≥2 APAs were input (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S3). Glutamatergic Synapse, Membrane Trafficking, and Circadian Entrainment are among the enriched terms.

The top 10 gene ontology terms and pathways identified by WebGestalt using the 1173 genes with APAs that exhibited time-of-day oscillations and had 2 or more total APAs. Minus log10 FDRs are plotted for each GO and pathway description.

We were interested whether rhythmic PASs might cluster predominantly into certain phases of peak expression, and whether APAs that share a common peak phase might also share some functional relationship. It was evident that some phases had very few APAs relative to other phases and the expression levels of many PASs peaked around ZT18-20 (Supplementary Fig. S1). When diurnal APAs from genes with ≥2 total APAs were grouped by phase, GO and pathway analysis on each group found that only phases 2, 10, and 18 had significantly over-represented terms. Phase 18 had the most, with the over-representation of multiple signaling pathways, including ‘neuron-to-neuron synapse’, ‘postsynaptic specialization’, and interestingly, genes in ‘mRNA processing’ pathways (Supplementary Table S4).

There is a growing appreciation that rhythms shorter than 24 h are biologically relevant35,36,37,38,39. Thus, we evaluated the PASs data for ultradian cycling using meta2d with the period set to 12 h. Overall, 1502 PASs that cycled with a 12 h period were identified (Supplementary Table S5). Of the 12 h cycling PASs, 1198 were in genes, and after adjusting for genes with multiple 12 h cycling APAs, there were 1149 unique genes in the set. In total, 827 of the 12 h cycling APA sites were in genes that had ≥2 APAs, representing 778 unique genes. Pathway analysis on this set of 778 unique genes (Supplementary Table S6) showed that CREB phosphorylation and circadian entrainment were highly enriched, while GO analysis of this dataset resulted in 16 GO terms related to the synapse.

PASs are differentially expressed after sleep deprivation and during recovery sleep

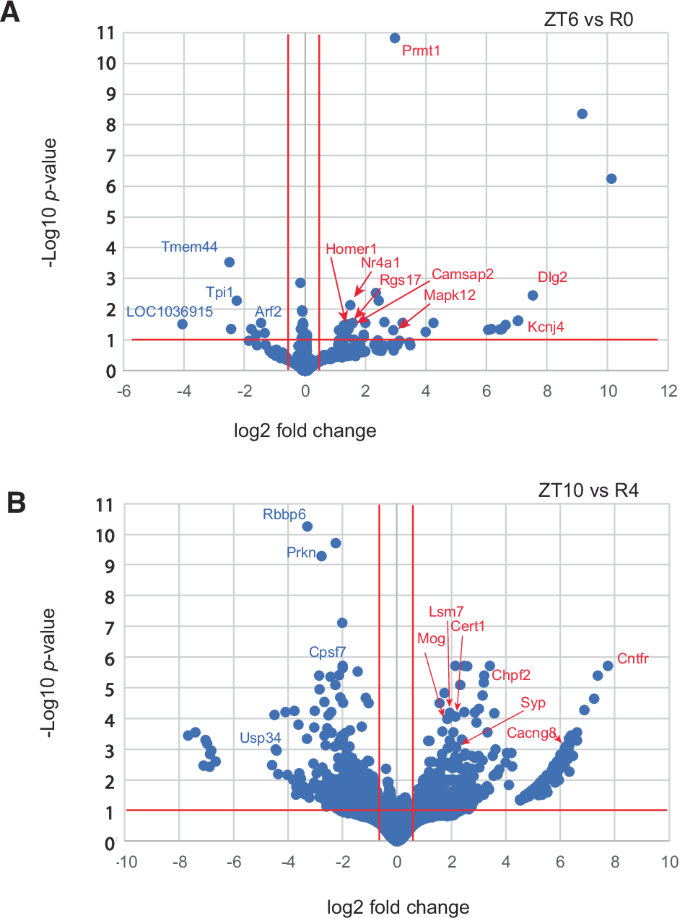

To investigate changes in APA site usage related to sleep pressure, rats were subjected to SD for 6 h from ZT0 to ZT6, and central forebrain tissue was collected immediately afterward (R0). Additional animals were allowed to recover for 2, 4, or 8 h after SD (R2, R4, and R8) before tissue was collected. WTTS-seq data from these samples were compared to time-matched controls that were allowed to sleep undisturbed (ZT6, ZT8, ZT10, and ZT14). All groups consisted of 5 biological replicates. Our sequencing data showed that the most significant differences in expression were seen when we compared R0 with its control (ZT6) and R4 with its control (ZT10) (Supplementary Table S7 and Fig. 3). Interestingly, a Homer1a APA isoform is the most abundant at R0, R4, and ZT6, whereas a full-length isoform is dominant at ZT10 (Supplementary Fig. S2a, b) Also, the expression of one APA isoform of Prmt1, was upregulated with high confidence after 6 h of sleep deprivation (Fig. 3). PRMT1 protein regulates multiple stress response pathways40,41, which have a roll in acute sleep loss.

Log of adjusted p-values are plotted against log2 fold changes from (A) ZT6 vs R0 and (B) ZT10 vs R4.

The gene names of differentially expressed APA sites from genes with ≥2 APAs were used for GO and pathway over-representation analysis (Table 2). ZT6 vs R0 only had significant results for GO while ZT10 vs R4 had significant GO and pathway results.

Comparison of APA-linked brain disorder susceptibility genes with WTTS-seq identified diurnal APAs and APAs differentially expressed with sleep pressure

A recent survey by Cui et al.31 using APA transcriptome-wide association studies (TWAS) highlighted the importance of APA site usage in brain disorders. To establish the extent to which genes with APA-linked neurological phenotypes had diurnal or sleep-related changes in rats, our list of diurnal genes with ≥2 APA sites were compared to those reported in Cui et al. 31. There were 25 overlapping genes (representing 28 APAs in our data since three genes had 2 diurnal APA sites). Another 19 genes with WTTS-seq-identified APA sites that cycle on a 12 h period were identified in the TWAS dataset, as were nine genes (11 APA sites) that were differentially expressed with sleep pressure. Altogether, 54 APAs representing 46 genes were observed in common with genes having disease-associated APAs (Table 3).

Discussion

APA site usage is an understudied aspect of gene regulation. Although APA sequencing can reveal changes in overall gene expression, it’s designed to focus on changes in APA usage and cannot reveal differences in splicing or transcription start sites (TSSs). On the other hand, bulk RNA-seq analysis often ignores APA, TSS and splice isoforms to simply assess reads per gene. Currently it would be very difficult to enumerate copies of all the mRNA isoforms for each gene. Yet appreciation is growing for the importance of APA sites in regulating mRNA stability17,42, mRNA/protein localization20,43,44, and human disease31,45.

Rhythmic APA site usage has been uncovered in the mouse liver22,23,46, and in temperature-entrained cultured cells, circadian APA usage occurs in many genes and can regulate expression of specific central clock genes24. Still, alternative poly(A) site usage hasn’t been given much attention in the sleep and circadian field. We therefore initiated this investigation into the conjunction of APA with sleep and diurnal expression. As far as we are aware, the current study is the first to examine APA sites related to circadian rhythms and sleep pressure in any mammalian brain. There are several, diverse ways in which data from this study can translate into biological relevance as described in the examples below.

Here, we observed that 6% of all PASs cycled with a 24 h period. One of the top pathways identified for the diurnal APA gene set was ‘circadian entrainment’ (Fig. 2). Since transcription-translation feedback loops are central to circadian regulation, this may not be surprising, but APA site usage suggests a more complex role24,46. For example, we find that one Sin3b APA follows a diurnal rhythm (Fig. 3A, B). Sin3b encodes short and long variants conserved in mammals. The short variant binds to CRY1 but cannot bind HDAC147. The long isoform is implicated in regulation of Per1/Per2 transcription48, along with many other genes49. In our data, long Sin3b APA reads constitute the predominant isoform at ZT6 and ZT22, while the short, diurnal isoform is the most abundant one at ZT10, ZT14 and perhaps ZT2 (Fig. 3B). Sin3b transcript levels in mouse hippocampus have previously been reported to be affected by sleep deprivation50, although this effect was not observed using TRAP-seq51, suggesting post-transcriptional processing can lead to changes in sleep-dependent differential expression. Together with our work, this example highlights the importance of utilizing various “-omic” approaches to properly decipher the complexity of molecular processing tied to changes in behavioral state in the brain.

Additional significant pathways emerged from the diurnal APAs, such as Oxytocin, Ephrin, and MAPK signaling that have demonstrated links to the circadian clock52,53,54. In the GO analysis of the diurnal genes with multiple PASs, we discovered that terms related to the synapse (12), protein localization (6), and vesicles (7) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S3) were enriched suggesting APAs are poised to affect neural communication.

A large proportion of diurnal APAs had expression peaks around ZT20 (Supplementary Fig. S1). Considering that rats are nocturnal, this is similar to what has been seen for bulk transcripts in several human tissues, including brain55. Interestingly, among the identified diurnal APA sites, 3 were in genes for RNA-binding proteins (Celf2, Elavl3, and Rbfox1) whose expressions correlate with more distal APA usage47. Peak expression of these three genes is from ZT21 to ZT1, so it would be interesting to see if transcripts of predicted targets tend to be longer at these times.

In addition to the 24 h circadian rhythm, recent studies have also demonstrated the existence of cell-autonomous ultradian clocks that run independently of the circadian clock to regulate 12 h oscillations in gene expression and metabolism35,36,37,38,39. Here we found that 5% of all PASs cycle with a 12 h period. Further analysis of these genes showed enrichment of gene ontology terms and pathways such as “regulation of trans-synaptic signaling” and “protein-protein interactions at synapses” (Supplementary Table S6), indicating that APAs could function to regulate cyclic actions of cell signaling and communication.

Gene expression studies following changes in sleep homeostasis have largely ignored alternative polyadenylation. Of the 31,795 total PASs characterized in rat forebrain in our study, we determined that 2.5% were differentially expressed with sleep deprivation and recovery sleep. Few PASs were differentially expressed at ZT14 vs R8 which may indicate that transcription/PAS use has recuperated after 8 h (Supplementary Table S7), and none were significant at ZT8 vs R2. The reasons for this result remain unclear as the total number of PASs recovered for ZT8 and R2 approximate the average of the other groups. It could be that transcription/PAS use is transitioning through a temporal window of recovery that closely resembles ZT8. Ample differentially expressed PASs were found at the other timepoints, and we observed six GO terms significantly enriched following 6 h of sleep loss and 26 following 4 h of recovery sleep (Table 2).

Human APA isoforms have been linked to many neurological disorders31. Among the genes that we identified to have rhythmic expression of APA sites or had APA sites that were affected by sleep pressure, we found that 46 have also been correlated with brain disorder susceptibility (Table 3). For example, the human MAPT/TAU gene produces transcripts containing short or long 3′ UTRs (Fig. 4C), and a 3′ single-nucleotide polymorphism, (SNP) is associated with both 3′ UTR length and risks for 8 neurological disorders, including Alzheimer’s (AD) and Parkinson’s diseases (PD)31. Homozygosity of the more common SNP variant is associated with short MAPT 3′ UTRs, homozygosity of the less common SNP variant is associated with long 3′ UTRs, and heterozygosity is associated with 3′ UTRs of intermediate lengths. In our rat APA data, there were both short and long 3′ UTR forms (5 in total) of the Mapt gene that were identified (Fig. 4C, D). Only two are currently annotated in the rat genome and one of the newly discovered APAs was observed to cycle with time-of-day. In mouse, binding of the ALS-associated protein TDP-43 to two sites in the 3′ UTR of Mapt has been shown to destabilize the mRNA56. In Alzheimer’s disease, the expression level of TDP-43 protein is often low, and TAU is overexpressed and eventually forms neurofibrillary tangles. The two TDP-43 binding sites that were experimentally determined in mouse are conserved in sequence and position in the rat gene, implying that transcripts with shorter 3′ UTRs would not be affected by TDP-43, while longer ones could be destabilized56,57. The presence of at least one putative TDP-43 binding site in the human MAPT 3′ UTR suggests that this may be contributing to the neurological disorder risk. Another interesting candidate is the miRNA 150-5p, which has been implicated in AD58,59,60, PD61,62, and possibly depression63. This mRNA has four putative binding sites in human MAPT/TAU 3′ UTR, of which two align at corresponding positions in the rat and mouse genes. Again, APAs producing the short transcripts would lack these sites (Fig. 4C).

A A map of the entire rat Sin3b gene depicts exons, introns and short and long APA sites (S and L). The corresponding genes in mouse and human are extremely similar. B The average normalized read counts ±SE (y-axis) of the short (diurnal) and long Sin3b APAs are plotted against time-of-day (x-axis). C Maps of the 3′ UTR regions of the human, mouse, and rat Mapt genes are shown. Arrows labeled 1–5 indicate the positions of APA sites found in rat. The human and mouse genes have 2 APAs depicted by red and black arrows respectively. In human MAPT, APA usage correlates with several brain disorders. RNA-seq coverage from individuals homozygous for the less common SNP allele that is associated with longer transcripts (adapted from Cui. et al. 27) is shown above the human MAPT 3′ UTR map. Binding sites for TDP-43 (indicated by red arrows) that were experimentally determined in mouse align with putative sites in the rat gene, and one possible TDP-43 binding site is indicated in the human 3′ UTR. The significantly diurnal APA is marked with an asterisk. Blocks of homologous sequence between the rat and human genes that were found by BLAST search are indicated by purple bars. Conserved predicted mir-181-5p binding sites are marked by red bars near the 3′ end in all three species, while two of the four predicted human mir-150-5p binding sites align with two in the rodent genes (black bars). The 3′ UTR lengths are 4380, 4119, and 3946 n.t. for human, mouse, and rat, respectively. D The average normalized read counts ±SE (y-axis) of the short Mapt isoforms lacking TDP binding sites (1 + 2) and the sum of the three longer isoforms (3 + 4 + 5) plotted against time-of-day (x-axis) are shown. E The 3′ UTR of tyrosine kinase-deficient (TK-) isoforms of the human, mouse, and rat Ntrk2 TK- genes are shown. Arrows indicate the positions of APA sites. The depicted rat APAs are from this current dataset. Diurnal rat APAs are indicated with asterisks. The 3′ UTR lengths are 5125, 5008, and 8004 n.t. for human, mouse, and rat, respectively. Mouse and rat sequence comparison by BLAST produced 4 segments having 91%, 83%, 86% and 82% identity for regions 1, 2, 3 and 4, depicted by blue bars.

Ntrk2 is among the APA TWAS genes linked to anxiety31 and has been associated with autism in other studies64. We found strong time-of-day oscillations of the 2 most abundant APA sites of the short, tyrosine kinase-deficient (TK-) Ntrk2 isoform. The TK- isoform of Ntrk2 has several known functions, including a dominant negative effect on the full-length TK+ isoform during neuronal proliferation, differentiation, and survival. In addition, the TK- version promotes filopodia and neurite outgrowth; sequesters, translocates, and presents BNDF; and affects calcium signaling and cytoskeletal modifications in glia65. Our WTTS-seq data revealed short, medium, and long 3′ UTRs in the rat Ntrk2 TK- isoform (Fig. 4E). In mice, the longer Ntrk2 TK- transcripts are preferentially targeted to apical dendrites66. Since the sequence of the rat 3′ UTR is highly conserved with the mouse sequence, it is plausible that an analogous dendritic localization mechanism is also in use in the rat (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, ‘Ntrk signaling’ was one of the pathways over-represented in the diurnal APA genes (Supplementary Table S3). APA sites in Src, Frs2, Atf1, Nras, Sh3gl2, Ntrk3, Mapk1, Grb2, Pik3r1, and Mapk14 contributed to this enrichment.

We found 118 genes that had a diurnal APA and an APA that cycles on a 12 h period. The Sorl1 gene is among these, exhibiting four different APAs with significant changes in our analyses; two diurnal, one cycled with a 12 h period, and one was reduced during recovery from sleep deprivation (Fig. 5). In total, there were seven APAs in the Sorl1 3′ UTR, three short, one medium and two long. The longest and most abundant isoform cycles per 12 h, the second longest and medium ones are diurnal and the shortest isoform is differentially expressed after SD (Fig. 5). SORL1 encodes an endosomal recycling receptor67, and a deficiency of SORL1 as well as many polymorphisms are strong risk factors for AD68,69. The mouse and human 3′ UTRs share extensive similarities including 5 APAs in mouse and 3 in human based on the PolyA_DB v3 (https://exon.apps.wistar.org/polya_db/v2/) and UCSC database70. Four microRNA binding sites with high probability of preferential conservation are in good alignment (TargetScanHuman v8.0)71. The first motif can be bound by five miRNAs (miR-25-3p, miR-32-5p, miR-92-3p, miR-363-3p, and miR-367-3p), while the second contains overlapping 7mer and 8mer motifs bound by miR-128-3p and miR-27-3p, respectively. The final two more distal sites are recognized by miR-153-3p and mir-137 (Fig. 5A). Sequences matching the consensus binding site for CPEB are present in the 3′ UTRs of all three species, with 2 in very good alignment. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein (CPEB) facilitates mRNA trafficking to synapses and local translation72,73, and we have previously shown that the core clock-controlled Fabp7 mRNA74,75 contains functional CPE sites in its 3′ UTR to regulate translation76. Since APOE4, an apolipoprotein E variant with increased risk of AD77, disrupts FABP7 interaction with sortilin, (an APOE receptor similar to Sorl1), to interfere with neuroprotective lipid signaling78, this suggests circadian variation in local translation of CPEB-mediated polyadenylation of target mRNAs may be a generalizable mechanism that modulates AD susceptibility through downstream lipid pathways. Any one or more of these conserved features could lead to conserved functional consequences dependent on APA choice.

A Maps of the human, mouse and rat Sorl1 gene 3′ UTRs show APA sites indicated by arrows. Four highly conserved miR binding sites are marked by red bars in all three species. The first 2 are recognized by multiple miRs. The size of dark blue bars under the rat APAs depict the individual proportion compared to the total of all WTTS Sorl1 reads. The human APAs are from established isoforms which also include different exon configurations. The first 4 mouse APAs are suggested by ESTs, and, in the latter 3 cases, by upstream polyA signals and PolyA_DB v3 data. Red ‘c’s indicate matches to the consensus CPE sites. B The proportion each Sorl1 APA contributes to the total for the gene are plotted for each of the diurnal timepoints. C The proportion each Sorl1 APA contributes to the total for the gene is plotted for the differentially expressed samples: ZT10 and 4 h after SD. D Graph of normalized read numbers of 4 Sorl1 APAs that either cycle with 24 h (M4 and L6) or 12 h (L7) hours and the one differentially expressed after SD (S1). Total reads and the corresponding scale are in red.

One caveat to our approach is that WTTS-seq generates Ion Torrent PGM sequences which may retain more noise compared to Illumina platform reads and since only Illumina has the option of paired-end reads, there can be more uncertainty in mapping Ion Torrent reads. Our strategy was to capture the maximum number of PASs, including the discovery of novel PASs, and the rat genome is not as thoroughly annotated as some other vertebrate species, we therefore included potentially intergenic reads. In our analysis, we found 5122 PASs and 318 diurnal PASs that mapped outside of known genes, and many APAs within genes mapped to regions in which 3′ ends have yet to be annotated. Based on prior WTTS-seq data sets and other PAS mapping approaches, some portion of our PASs could be method-based artifacts27,79, (see Zhou et al. 27. Figs. 3, 4 and 5). In this, our initial PAS survey, we assayed a large portion of the brain. Therefore, future studies in restricted brain structures or cell types will be required to uncover APAs that cycle or are differentially expressed at a finer scale. Overall, the newly discovered PASs should add valuable insights into regulation of the rat transcriptome and for characterizing PAS usage in the mammalian brain.

Here we used an unbiased discovery-based approach for uncovering novel APA usage following time-of-day or changes in sleep pressure in mammalian brain. These data leverage a call to action for additional work to elucidate the core mechanisms of PAS usage in the brain and to examine the capacity of APA to affect the transcriptomes and proteomes that regulate central brain processes known to be altered by time-of-day and sleep/wake homeostasis. Moreover, it known that PAS usage varies across brain region and cell-type21 (i.e., substructure-, circuit-, laminar- or nucleus-specific)80. These hypothesis-generating data provide an impetus for continued research aimed at delineating how sleep and circadian rhythms impact mental health and neurodegenerative disease.

Methods

Subjects

All animal procedures were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and ARRIVE and OLAW guidelines and approved by the WSU Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC; ASAF# 6804). Male Long Evans rats (7–9 weeks old) were housed in pairs at 22 ± 2 °C on a 12:12 h light-dark cycle. The rats were acclimated to this light cycle for at least 10 days prior to tissue collection, with water and chow ad libitum. Cages were cleaned weekly (between 8 and 11 AM) unless the rats were being euthanized within 24 h. Thirty rats were randomly assigned to one of six groups (n = 5/group) that were sampled every 4 h, beginning 2 h after light onset (zeitgeber time (ZT)) (i.e., ZT2, 6, 10, 14, 18, and ZT22). For the sleep deprivation (SD) study, twenty rats were randomly assigned to 6 h SD from ZT0–6, wherein rats were kept awake by an automated bedding stir bar (Pinnacle) at the bottom of a cylindrical cage. The bar was set to rotate for 4 s, randomly changing rotation direction, and stopped for a random interval ranging from 10 to 30 s81,82. Following SD, rats (n = 5/time point) were euthanized immediately (R0) by live decapitation or were returned under red light to their home cage for 2 h (R2), 4 h (R4), or 8 h (R8) without disruption before sampling. Five additional rats were euthanized at ZT8 as undisturbed, time-matched controls. The other time-matched controls with undisrupted sleep (i.e., ZT6, 10, and 14) were taken from the corresponding time-of-day matched samples described above. Ambient lighting was matched in all R vs ZT rat pairs. No animals or data points were excluded.

Tissue collection

Rats were decapitated by guillotine under normal room light (ZT2–10) or under dim red light (ZT14–22). Following decapitation, forebrains were resected (Fig. 1A), frozen in 2-methylbutane suspended in dry ice, and then stored at −80 °C until homogenization for RNA extraction. Following tissue collection, total RNA isolates were coded and sent for WTTS-Seq and remained blinded until analyses.

RNA isolation

Just before RNA isolation, forebrains were removed from −80 °C storage and placed on dry ice. Prior to use, a stainless-steel mortar and pestle were cleaned with RNase Zap (Thermo Fisher) and 70% ethanol. The mortar was then partially filled with liquid nitrogen before a forebrain was added, pulverized, and placed in a conical tube. Between each sample, the mortar and pestle were cleaned with 70% ethanol. A small aliquot of sample was removed for RNA isolation using Trizol Reagent (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified RNA was resuspended in water, and concentration and purity were measured with a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher). Samples were stored at −20 °C until further processing was performed.

Library preparation

WTTS-seq libraries were prepared as described by Zhou et al. 27. Briefly, total RNA (2.5 µg) was incubated at 70 °C with 10× Fragmentation buffer (Invitrogen) for 3 min. The fragmentation reaction was halted by the addition of Stop Solution and incubation on ice for at least 2 min. Next, poly(A) + RNA was purified from the fragmented total RNA with Dynabeads Oligo (dT)25 (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s directions, and used for first-strand cDNA synthesis in a 20 µL reaction mixture. First, 1.0 µL of barcode primer (100 µM) and 1.0 µL of a common SMART primer (100 µM) were annealed to the poly(A) + RNA template by heating to 65 °C for 5 min and incubating on ice for at least 2 min. Next, 4.0 µL of 5x First-strand buffer (Invitrogen), 1.0 µL of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen), 1.0 µL of 0.1 M dithiothreitol, 2.5 µL of 10 mM dNTP, and 1.0 µL of RNase OUT (Invitrogen) were added to the mixture. First-strand cDNA was synthesized by incubating the mixture at 40 °C for 90 min in the presence of library-specific adaptors. Synthesis was terminated by heating the mixture at 70 °C for 15 min. RNases I (100 U/µL; Invitrogen) and H (2 U/µL; Invitrogen) were subsequently added and incubated with the mixture at 37 °C for 30 min to hydrolyze the remaining single-stranded RNA molecules and ensure that only single-stranded cDNA remained. RNase activities were terminated by heating the samples at 70 °C for 20 min. Following purification with solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads, second-strand cDNA was synthesized from first-strand cDNA by asymmetric PCR. In addition to the cDNA, the 50 µL PCR reaction contained 1.0 µL of Phusion Hi-Fidelity DNA polymerase, 10.0 µL of 5X HF buffer, 1.0 µL of 0.4 µM barcode primer, 1.0 µL of 0.8 µM common primer, 1.0 µL of 10 mM dNTP, and nuclease-free water. The PCR reaction was carried out by heating at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 20 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 50 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s, with a final elongation step at 72 °C for 10 min. SPRI beads were used to purify and select 200–500 bp fragments from the final library. After quality control analyses, the size-selected library was sequenced with an Ion PGM Sequencer at the WSU Genomics Core Laboratory.

Raw read processing

Raw data were obtained from 55 samples and stored in FASTQ format. We filtered raw reads with the FASTQ quality filter in the FASTX Toolkit (v0.0.13), allowing for a minimum score of ≥10 for ≥50% of bases (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/). We trimmed T nucleotides or T-rich sequences located at the 5’ ends of the reads using Perl scripts, as described previously27. Trimmed reads of at least 16 bp in length were kept for further analysis.

Read mapping and poly(A) site clustering

For each dataset, the processed reads were aligned to the Rattus norvegicus genome (mRatBN7.2/rn7) using the torrent mapping program (TMAP, v3.4.1; http://github.com/iontorrent/tmap) with the unique best hits parameter (-a 0). Raw PASs supported by the uniquely mapped reads were extracted from SAM files and merged into a polyadenylation tag (PAT) file with a script previously used for WTTS-seq (freely available by contacting Dr. Zhihua Jiang, Washington State University). The PAT files were merged to determine the final PASs for all samples. PASs within 25 nucleotides of one another were grouped into one polyadenylation site cluster (PAC) using GetPolyaSiteCluster83. PACs were filtered taking into account the library size. For libraries that had less than 1.7 M reads, PACs were required to have ≥1 set of 5 biological replicates had ≥3 samples with ≥3 reads. For libraries with more than 1.7 M reads, at least 3 samples with ≥4 reads were required.

Gene annotation and usage of poly(A) sites

We annotated all the final PACs for PAS_ID, gene symbol, functional region, and other factors, as indicated, using Cuffcompare (v2.2.1)84, Perl scripts, and annotation file (GCF_000001895.5_Rnor_6.0_genomic.gtf; https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Clusters that mapped to mitochondrial genes were removed, then the number of PAS-covered reads was normalized85 to the total number of covered reads within each library and rescaled by a factor of 107.

Diurnal/ultradian PAS discovery

Using normalized PAS read counts as input, rhythmic patterns were identified using the MetaCycle32 R package meta2d, which synthesizes the results of three cycle analysis algorithms (ARSER, JTK_Cycle, and Lomb-Scargle). The five replicates were arranged sequentially over five days since at least two complete cycles of data are recommended86, and the analysis was run five times with different replicates inserted into each of the appropriate ZT time slots, and the median p-value, median BH.Q, average phase, amplitude, and relative amplitude were calculated according to32. We found when 5 meta2d runs were combined, they out-performed randomized data much better than a single run. Following the meta2d analysis as referenced in86, only the highly corroborated PASs that were significant (p < 0.05) in all five trials were used for all analyses. Plots of read counts use normalized reads per 107 and show the SEM of five biological replicates.

Detailed mapping of APA sites

The data supporting all figures depicting APA sites was from rat genome build BN7.2 and the UCSC (http://genome.ucsc.edu) and RDG (https://rgd.mcw.edu/rgdweb/homepage/) genome browsers70,87.)

Gene ontology and pathway analysis

Gene over-representation analysis was performed with the web-based tool WebGestalt34. Input gene symbol sets representing genes with cycling APA sites (p < 0.05 in 5 of 5 trials and >1 PAS) or APA sites that were differentially expressed with sleep pressure (p < 0.01, log2FC > 0.5 and >1 PAS), were compared to relevantly annotated rat genes using an output threshold of FDR ≤ 0.05. For phase-specific analysis, a sliding window of 5 h centered on each sample collection time point was used. For example, for phase ZT6, all PASs with average phase calculations that ranged from 3.5 to 8.5 were grouped. This produced a sufficient number of PASs to do gene over-representation analysis. The 0.5 h overlap in adjacent phase clusters was to account for uncertainty in phase calls.

Differential expression analysis of sleep deprivation/recovery

To evaluate the expression of PASs in sleep homeostasis experiments, PAS counts from rats recovering from 6 h SD were contrasted with time-matched controls (R0 vs ZT6, R2 vs ZT8, R4 vs ZT10, R8 vs ZT14). We removed high variation from the first principal component systematically, resulting in improved variance estimates for low read counts. Prcomp (in R) was used to perform principal component analysis (PCA) and to find eigenvectors by way of singular value decomposition. DESeq-2 with “Apeglm” Shrinkage88 and the Wald Test were used to generate test statistics in R software. The FDRtool was used to determine the Local FDR.

Responses