Social jetlag alters markers of exercise-induced mitochondrial adaptations in the heart

Introduction

In modern societies, natural cycles of sunlight and dark have been replaced by artificial light sources, allowing behavior and necessity to dictate exposure to our strongest circadian cue, light. Mistimed exposure to light can disrupt the natural ~24-h rhythms in physiology that exist within virtually all organisms at the cellular-, tissue-, and behavioral levels. This disruption is especially pronounced in people working a night shift schedule, where circadian rhythm disruption has been associated with increased inflammation and incidence of cardiovascular diseases1,2,3,4,5. While only a fraction of the population participates in shift work, a far greater number of people experience social jetlag (SJL), an alternative and pervasive form of circadian rhythm disruption resulting from frequently changing environmental and behavioral cues.

SJL represents the misalignment between behavioral schedules on free vs workdays, and is calculated as the absolute difference in the mid-sleep phase on free days and work days6. For example, many “weekday behaviors” (including sleep/wake times, meals, etc) are dictated by rigid schedules in professional or educational settings. On weekends however, many people alter their behaviors to accommodate their social preferences. This often leads to individuals choosing to delay their sleep/wake schedule, going to bed and waking up later on weekends. This contrast in weekday and weekend schedules affects circadian rhythms similarly to conventional jet travel across time zones7,8.

SJL is extremely prevalent, with 70-80% of people undergoing at least one hour of SJL, and 30–40% undergoing two or more hours of SJL6,9,10,11. Sleep irregularity, including SJL, is associated with adverse cardiovascular and metabolic health12,13. In fact, Madiera et al. identified a dose-dependent increase in cardiovascular risk with each hour of SJL14. Additionally, many experience shorter sleep during the week and subsequently “catch up” on sleep over the weekend. Though reducing the burden of short sleep during the week seems appealing, catch up sleep is also associated with higher incidence of chronic metabolic conditions15. As such, there is a necessity for basic/mechanistic investigations into the effects of SJL on the heart.

Several studies in animals have investigated the effects of SJL on the expression of clock genes, and patterns of activity in mice. A 6-h light:dark cycle shift on weekends caused an immediate phase delay in locomotor activity and circadian clock gene expression, but when light:dark cycles returned to the “weekday” schedule, delays in activity onset persisted after five days (or a usual work week)16. Assuming that SJL occurs every weekend, this would suggest that in the case of extreme social jetlag, there is chronic desynchrony between behavioral rhythms and circadian clocks. Subsequent studies revealed that voluntary access to a running wheel accelerated the rate of reentrainment, which returned to baseline by five days while sedentary mice did not17. SJL may also inhibit adaptations to exercise training in mice13 and increase the risk of musculoskeletal injury in humans18.

Circadian rhythms are driven by molecular circadian clocks located throughout the body which serve to regulate functions in a time-of-day dependent manner19,20. In the cardiovascular system, circadian clocks have been shown to regulate a host of physiological processes including transcription21,22,23 contractility24, metabolic responsiveness to different substrates25,26, and mitochondrial turnover/health27,28,29. In order to maintain quality control and proper function, mitochondria undergo fusion (merging mitochondria) and fission (mitochondria splitting), to interchange mitochondrial DNA and enzymes, or eliminate defective mitochondria, respectively30. Mitochondrial fusion is primarily controlled by the proteins mitofusin 1 (MFN1) and mitofusin 2 (MFN2), which connect and fuse the outer membrane of the mitochondria, while optic protein atrophy 1 (OPA1) is involved in fusion of the inner mitochondrial membrane31. In contrast, dynamin-like protein 1 (DRP1) and fission 1 (FIS1) are responsible for the initiation of mitochondrial fission31,32. Previous studies have shown a direct regulation of mitochondrial dynamics proteins by the circadian clock, including DRP133 and BNIP327. Disruption of the circadian rhythm, or clock components, could therefore facilitate cardiovascular disease, potentially through hampered mitochondrial dynamics27,29.

Exercise training results in increased expression of fusion and fission proteins34,35,36, as both are necessary for mitochondrial homeostasis and optimal energy production37. Circadian rhythm disruption, however, leads to impaired mitochondrial dynamics in the heart. When myocardial circadian clock genes are inactivated daily oscillations in heart metabolism are compromised24. Other models of circadian rhythm disruption, such as inverting the LD cycle every three days, impair both fission and fusion gene expression in mice38.

To this point, there are no investigations of chronic or prolonged SJL on myocardial adaptations to exercise. Furthermore, whether SJL impedes exercise-induced cardiovascular adaptations, including mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics, remains unknown. For that reason, the purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of SJL on the myocardial adaptations elicited from voluntary exercise training in mice.

Materials and methods

Mice and housing

To complete this study, 40 adult male C57BL/6 mice (10 weeks of age) were randomly allocated to 4 experimental groups (n = 10/group); 1) Sedentary mice housed on a Control LD cycle (CON-SED), 2) Sedentary mice housed on a SJL schedule (SJL-SED), 3) Exercised mice housed on a Control LD cycle (CON-EX), and 4) Exercised mice housed on a SJL schedule (SJL-EX). At the beginning of the experimental protocol, mice were single housed in temperature and humidity controlled microisolator cages (~23 °C, 20% humidity). The Control LD cycle was a strictly enforced 12:12 flipped cycle with beginning of the light cycle (ZT0) at 3:00 AM and the beginning of the dark cycle (ZT12) at 3:00 PM, to allow for all animal handling to be performed during the dark/active period under dim red light. All animals had ad libitum food access for the duration of the study. Experimental conditions persisted for 6 weeks. At the conclusion of the study (at least 24 h after the last active period with running wheels), mice were euthanized ~ZT5 (to minimize circadian variation), and hearts were tested for gravimetric and molecular markers of exercise-induced adaptations. Tissues were flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent analysis. Members of the research team were not blinded to the animal groups during handling or analysis. All aspects of the present study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Nevada Las Vegas.

Social jetlag

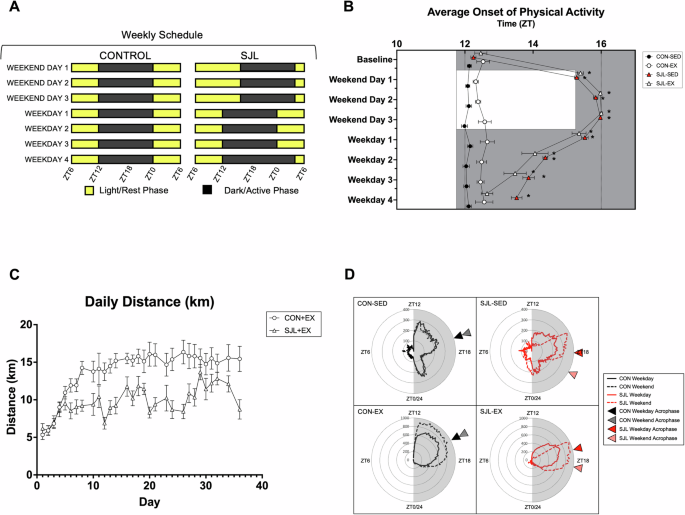

A simulated SJL schedule was performed by moving the mice between two vivarium rooms on differing LD schedules, the Control LD schedule (described above, representing the ‘weekday’ schedule), and a room delayed by 4 h (lights on/ZT0 at 7:00 AM and lights off/ZT12 at 7 PM) and is shown in Fig. 1A. During the ‘weekdays,’ all mice were housed in the room with the Control LD schedule. On weekends, a 4-hour phase delay (lengthening the dark period by 4 h) was induced starting on Fridays by moving the SJL mice to the room on the SJL LD schedule, persisting through the weekend. SJL mice returned to the original LD schedule three days later, undergoing a 4-h phase advance.

Representation of the social jetlag schedule with four days of normal LD cycle, a four-hour phase delay to begin the weekend, and a four-hour phase advance to begin the week (A). Average onset of physical activity with baseline days 1–5, average Weekend (WE) days 1–3, and average Weekday (WD) days 1–4 (B). Daily running distance (km) for CON-EX and SJL-EX (C). Radar plot depicting average weekday/weekend activity (cage PIR sensor/wheel) (D). (*) p < 0.05 relative to baseline.

Voluntary wheel running exercise

Mice in the exercise groups (CON-EX and SJL-EX) were provided a wireless running disc (Med Associates, Fairfax, VT), and underwent 6 weeks of voluntary wheel running exercise. Wheel access was provided ad libitum. Exercise volume was monitored with accompanying Wheel Manager software. Running distance was monitored in 10-min bins continuously over the 6-week period and summed to represent daily distance. Sedentary mice were provided with a running disc without the base on which it revolves to account for cage enrichment.

Passive infrared activity monitoring

Sedentary mice were individually housed in cages with a passive infrared (PIR) sensor attached to the cage to monitor circadian rhythms in activity without the exercise stimulus provided by the running disc. The PIR sensor was developed and validated with open-source software as an accurate and reliable way to monitor locomotive behavior in mice39. Activity data was generated by the PIR and digitally recorded on a flash disc with a 1-min bin. Activity data was subsequently processed in 10-min bins to monitor total activity, as well as the circadian rhythm in activity.

Circadian rhythm assessment

The circadian rhythm of activity was monitored in sedentary mice using the PIR data, and exercised mice using the running disc data. Activity data was evaluated for the onset of physical activity, which was determined as the transition from the 6-h period of lowest activity to the 6-h period of higher activity16,17.

Western blotting

Frozen hearts were powdered with mortar and pestle in liquid nitrogen, and ~20 mg of powdered tissue was homogenized with lysis buffer with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were electrophoresed on polyacrylamide gels (6%, 10%, 4–20%), and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. After blocking with 5% nonfat dry milk, membranes were treated with primary antibodies for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC1-α; Novus Biologicals, NBP1-04676), phosphorylated mammalian target of rapamycin (p-mTOR; Cell Signaling, 5536), mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR; Cell Signaling, 2983), mitofusin 1 (MFN1; Novus Biologicals, NBP1-51841), mitofusin 2 (MFN2; Cell Signaling, 9482S), optic atrophy gene 1 (OPA1; Cell Signaling, 80471S), mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS1; Proteintech, 10956-1-AP), phosphorylated dynamin-related protein 1 (p-DRP1; Cell Signaling, Ser616), dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1; Cell Signaling, 4E11B11), or a cocktail antibody containing specific constituent proteins within the five oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) complexes (CI – NDUFB8, CII – Succinate Dehydrogenase B (SDHB), CIII – ubuquinol-cytochrome c reductase core protein 2 (UQCRC2), CIV – mitochondrially encoded cytochrome C oxidase I (MT-CO1), and CV – ATP5A, Abcam, [ab110413]). Antibodies were diluted 1:1000 in 5% BSA based blocking reagent and applied overnight. HRP-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies wereused to visualize protein expression with ECL substrate (BioRad ChemiDoc, Hercule, CA), and the resulting images were analyzed using ImageJ software. A complete assembly of uncropped and unedited western blot images can be found in supplementary files.

RNA Isolation and RT-PCR

RNA was isolated from ~20 mg of powdered heart tissue using conventional trizol isolation methodology, and the concentration and purity was assessed spectrophotometrically (NanoDrop 2000, Wilmington, DE). Approximately 1000 ng RNA was then converted to cDNA using commercially available cDNA synthesis kits (BioRad), and diluted to 5 ng/uL with DEPC water. Master mixes containing forward and reverse primers and SYBR Green SuperMix (Quanta Biosciences, Beverly, MA) were prepared and loaded into 96 well plates with 25 ng cDNA/reaction. Amplification of target genes was tracked in real time fluorescently through 40 PCR cycles on a CFX Connect ThermalCycler (BioRad). Canonical circadian clock genes were evaluated using specific primer sequences listed below: Bmal1 F’ – CACCAACCCATACACAGAAG, Bmal1 R’ – GGTCACATCCTACGACAAAC, Per1 F’ – CAGACCAGGTGTCGTGATTAAA, Per1 R’ – CGAAACAGGGAAGGTGAAGAA, Per2 F’ – ATGAGTCTGGAGGACAGAAG, Per2 R’ – CCTGAGCTGTCCCTTTCTA, Clock F’ – ACTCAGGACAGACAGATAAGA, Clock R’ – TCACCACCTGACCCATAA, Rev-erb-α F’ – TGGCCTCAGGCTTCCACTATG, Rev-erb-α R’ – CCGTTGCTTCTCTCTCTTGGG, Cry1 F’ – AGAGGGCTAGGTCTTCTCGC, Cry1 R’ – CTACAGCTCGGGACGTTCTC, Cry2 F’ – GTCTGTGGGCATCAACCGA, Cry2 R’ – TGCATCCCGTTCTTTCCCAA, Actb F’ – CTTGGGTATGGAATCCTGTG, Actb R’ – GCATAGAGGTCTTTACGGATG. Gene expression was quantified using the 2^∆∆Ct method and reported as ‘fold change from CON-SED’ for each gene.

Statistical analysis

Average onset of physical activity, average daily distance, PIR activity, protein expression, gene expression, and tissue weights were all analyzed using two-way ANOVA tests. Values greater than 2 standard deviations from the group mean were treated as outliers and removed from analysis. When significant interactions were found, Tukey’s honestly significant difference post hoc tests were run. All data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Unless otherwise noted, the level for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9 (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Results

Social jetlag induces weekly shifts in behavior of sedentary and exercised mice

To evaluate the chronic effect of SJL, the activity onset was averaged for baseline days (before SJL began), each Weekday and Weekend Day throughout the study, such that the averages of all five SJL shifts were analyzed. At baseline, before any SJL shifts occurred, Sedentary groups (CON-SED and SJL-SED) and Exercise groups (CON-EX and SJL-EX) demonstrated similar times of onset of physical activity (Fig. 1B). SJL caused an immediate and significant delay in the time of onset of physical activity in SJL-SED and SJL-EX on the first day of the ‘weekend’ LD schedule (SJL-SED: Weekend Day 1 = 15.28 ± 0.07 vs Baseline = 12.25 ± 0.08, p < 0.001; SJL-EX: Weekend Day 1 = 15.39 ± 0.09 vs Baseline = 12.47 ± 0.18, p < 0.001). On weekdays, SJL mice did not immediately return to baseline onset of physical activity times, but gradually shifted toward ZT12 as the week progressed. Exercise promoted more rapid reentrainment to the weekday LD schedule, as SJL-EX onset of physical activity returned to baseline at Weekday 4 (SJL-EX: Baseline: 12.047 ± 1.79; Weekday 4: 12.65 ± 0.17, p < 0.928), while SJL-SED was still significantly delayed (SJL-SED: Baseline: 12.25 ± 0.08; Weekday 4: 13.38 ± 0.04, p < 0.001). Daily wheel running distances of exercised mice were analyzed, and revealed that while both groups ran similar distances during the baseline week, SJL-EX ran significantly lower distances for weeks 2-4, and similar distances during weeks 5 and 613. Additionally, average weekday and weekend activity (cage/wheel) was averaged for each mouse throughout the duration of the study, and visualized on a radar plot (Fig. 1D). The acrophase of average activity for each group was assessed, which shows identical Weekday/Weekend acrophase of activity in CON-SED (ZT17.1) and CON-EX (ZT18.1). SJL mice demonstrated delays in the activity acrophase in SED (SJL-SED WD = ZT18.1 vs WE = ZT19.8) and EX mice (SJL-EX WD = ZT17.1 vs WE = ZT18.4).

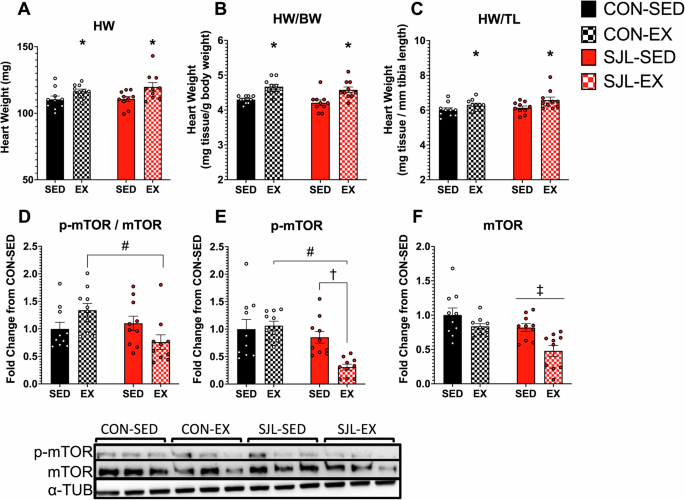

SJL does not inhibit exercise-induced myocardial hypertrophy

To evaluate myocardial hypertrophy, heart mass was analyzed by absolute weight (mg tissue) (Fig. 2A), and normalized to body mass (HM/BM in mg tissue/g body mass) (Fig. 2B), and standardized to tibia length (HM/TL in mg tissue/mm tibia length) (Fig. 2C). There was a main effect of EX for increased absolute heart mass (p = 0.003), HM/BM (p < 0.001), and HM/TL (p = 0.007), providing evidence that that voluntary wheel running was sufficient to induce cardiac hypertrophy, and SJL did not attenuate this response.

Absolute and relative heart mass and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways. Raw heart mass (A), heart mass standardized to body weight (B), heart mass standardized to tibia length (C), phosphorylated mTOR (D), mTOR (E), and p-mTOR to mTOR (F). Values are displayed as means ± SEM. (*) p < 0.01, EX relative to SED; (#) p < 0.01 SJL-EX relative to CON-EX; (†) p < 0.05 SJL-EX relative to SJL-SED; (‡) p < 0.01 SJL relative to CON; (#) p < 0.05 SJL-EX relative to CON-EX.

To investigate a potential pathway for myocardial hypertrophy, p-mTOR (Fig. 2D) mTOR (Fig. 2E) and p-mTOR/mTOR (Fig. 2F) protein expression was analyzed. For p-MTOR, a significant interaction effect was found (p = 0.012), and post-hoc analysis revealed decreased p-mTOR expression in SJL-EX compared to SJL-SED (SJL-EX: 0.308 ± 0.054 vs SJL-SED: 0.851 ± 0.108, p = 0.010) and CON-EX (SJL-EX: 0.308 ± 0.054 vs CON-EX: 1.063 ± 0.082, p < 0.001). For total mTOR, significant main effects for both SJL (p < 0.001) and exercise (p = 0.002) reveal lowered total mTOR expression compared to control LD schedule, and sedentary mice, respectively. We also observed a significant exercise x SJL interaction effect in p-mTOR / mTOR ratio (p = 0.011). Post-hoc analysis revealed significantly lower p-mTOR expression in SJL-EX compared to CON-EX (SJL-EX: 0.759 ± 0.132 vs CON-EX: 1.338 ± 0.124, p = 0.014)

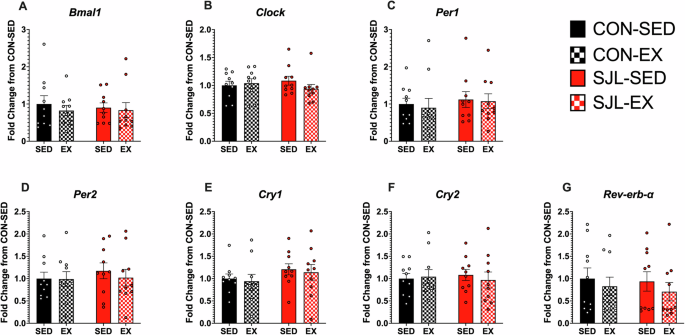

Neither SJL nor exercise altered myocardial circadian clock gene expression

No main effects or interactions were observed for any of the circadian clock genes in the heart (Interaction Effects: Bmal1: p = 0.761; Clock: p = 0.248; Reverb-ɑ: p = 0.897; Per1: p = 0.898; Per2: p = 0.681; Cry1: p = 0.979; Cry2: p = 0.810;) (Fig. 3).

Gene expression standardized to β-Actin expression and quantified as fold change con CON-SED. Gene expression shown for Basic Helix-Loop-Helix ARNT Like 1 (Bmal1) (A), Circadian Locomotor Output Cycles Kaput (Clock) (B), nuclear receptor subfamily 1 group D member 1 (Rev-erb-ɑ) (C), Period Circadian Regulator 1 (Per1) (D), Period Circadian Regulator 2 (Per2) (E), and cryptochrome circadian regulator 1 (Cry1) (F), and cryptochrome circadian regulator 2 (Cry2) (G).

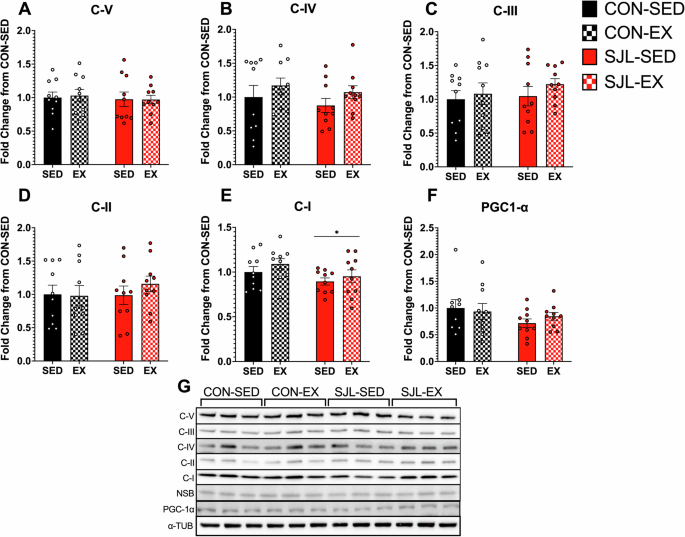

Neither SJL nor exercise altered mitochondrial content

To assess potential exercise-induced adaptations in mitochondrial content, we evaluated the myocardium for expression of constituent proteins found within mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complexes (OXPHOS, Fig. 4A) and PGC-1α (Fig. 4B). While SJL caused a decrease in Complex I protein expression relative to CON (Main Effect; SJL, p = 0.048), no other main effects or interactions were observed in any other OXPHOS complexes (Interaction Effects: C-V: p = 0.851; C-IV: p = 0.919; C-III: p = 0.725; C-II: p = 0.491; C-I: p = 0.784) or PGC-1α (p = 0.426).

Western blot quantification for OXPHOS CV alpha subunit (C-V) (A), CIV subunit I (C-IV) (B), CIII-Core protein 2 (C-III) (C), CII-30kDa (C-II) (D), CI subunit NDUFB8 (C-1) (E), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator (PGC-1α) (F). Representative images for OXPHOS (G) and PGC-1α (H). (*) p < 0.05 SJL relative to CON.

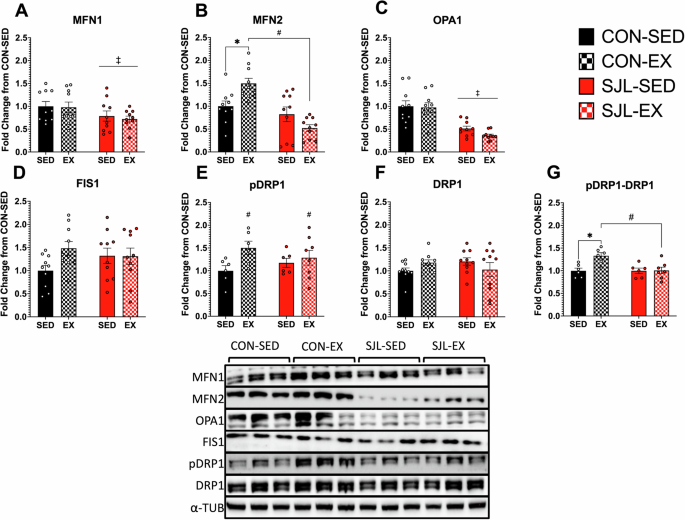

SJL inhibits exercise-induced changes in markers of mitochondrial dynamics

Mitochondrial dynamics were evaluated by measuring protein expression of markers of mitochondrial fusion and mitochondrial fission. ANOVA analysis revealed a significant reduction of MFN1 expression in SJL mice compared to CON (Main Effect SJL; p = 0.027) (Fig. 5A). For MFN2 expression, a significant SJL x Exercise interaction effect was observed (p = 0.002). Post-hoc analysis revealed that exercise resulted in a significant increase in MFN2 production in CON-EX relative to CON-SED (CON-SED: 1.00 ± 0.113: CON-EX: 1.497 ± 0.112, p = 0.027), but SJL significantly blunted the increased MFN2 expression in SJL-EX (CON-EX: 1.497 ± 0.112; SJL-EX: 0.522 ± 0.073, p < 0.001). Both SJL-SED and SJL-EX showed similar MFN2 expression (SJL-SED: 0.823 ± 0.160; SJL-EX: 0.522 ± 0.073, p = 0.294). We also found that SJL led to a significant decrease in OPA1 expression independent of exercise (Main Effect SJL; p < 0.001). Taken together, SJL attenuated expression of markers of mitochondrial fusion.

Representative Western blot images and quantification of mitofusion 1 (MFN1) (A), mitofusin 2 (MFN2), (B), optic atrophy gene 1 (OPA1) (C), mitochondrial fission 1 protein (FIS1) (D), phospho-dynamin-related protein 1 (p-DRP1) (E), dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) (F), and p-DRP1 to DRP1 ratio (pDRP1-DRP1) (G). (‡) p < 0.05, SJL relative to CON; (*) p < 0.05, CON-EX relative to CON-SED; (#) p < 0.05, CON-EX relative to SJL-EX.

Activation of DRP1 was measured by the ratio of p-DRP1/DRP1. There was a significant main effect of exercise for increased p-DRP1 expression relative to SED mice (p = 0.041). When the p-DRP1 – DRP1 ratio was analyzed, a significant interaction effect was revealed (p = 0.023). Post-hoc analysis further revealed that while CON-EX had an increased p-DRP1 – DRP1 ratio compared to CON-SED (CON-SED: 0.998 ± 0.058; CON-EX: 1.330 ± 0.070, p = 0.015), SJL-EX had a blunted pDRP1-DRP1 ratio expression (CON-EX: 1.330 ± 0.070; SJL-EX: 1.006 ± 0.072, p = 0.010). There were no main effects or interactions for FIS1 protein expression.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to directly investigate the effects of chronic SJL on circadian rhythms and exercise-induced myocardial adaptations. The major finding of this study was that SJL impacted exercise-induced increases in markers of mitochondrial fusion and fission despite observing no changes in mitochondrial content.

In the present study, exercise caused an increase in MFN2 protein expression. MFN2 is a downstream target of PGC-1α, and is demonstrated to increase mitochondrial fusion in the heart40,41,42. These findings agree with previous work that demonstrated after two weeks of treadmill exercise training, myocardial MFN2 protein expression was increased in rats35. In contrast, No et al. had rats perform treadmill exercise for 60 min, five days a week for eight weeks36. In young rats, they found no effect of exercise for MFN2 or OPA1, but a significant increase in MFN1 expression36. Taken together, endurance exercise training usually leads to increases in proteins responsible for mitochondrial fusion.

The present study demonstrated that SJL-induced alterations in the circadian rhythm of activity was sufficient to influence mitochondrial dynamics. While markers of mitochondrial fusion increased with exercise under normal LD conditions, MFN2 and OPA1 protein expression were blunted by SJL even though they still maintained ~10 km voluntary exercise per day. SJL disruption of the circadian rhythm may contribute to this decreased expression. MFN2 and OPA1 have both been shown to have decreased gene expression in both BMAL1 knockout mice and in mice with inverted L:D schedules every three days38. Abnormal mitochondrial fission or fusion impedes ATP production, exacerbates free radical production43, and impairs enzymatic activity within the mitochondria, which can lead to cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and early aging44.

Mitochondrial fission is a crucial process that helps maintain homeostasis in the heart tissue and maintain quality control generally37. Mitochondrial fission and fragmentation in the heart can indicate pathologies and defective mitochondria37,45. DRP1 knockout mice surprisingly maintain regular mitochondrial function, but ultimately end in heart failure due to inability to clear out dysfunctional mitochondria46. Under normal physiologic conditions, mitochondrial fusion occurs acutely as an adaptation to exercise. Coronado et al. demonstrate the role of fission in the heart in enhancing mitochondrial function34. During both submaximal and maximal exercise, they demonstrated that DRP1-induced mitochondrial fission occurs in the heart and is needed to meet energy demands needed to reach maximal exercise capacity34. While Coronado’s tissues were taken acutely post exercise, the present study provides evidence that pDRP1 is elevated with chronic exercise. When pDRP1-DRP1 expression ratio was analyzed, however, SJL-EX had a blunted response compared to the increased expression in CON-EX, suggesting that the disruptive effect of SJL may be inhibiting exercise-induced mitochondrial fission. Previous studies using chronic, regular shifts in LD cycles impaired normal diurnal rhythms and lower overall RNA expression of DRP138. Schmitt and colleagues demonstrated that the phosphorylation of DRP1 is under circadian clock control, and blocking DRP1 activity severely impaired ATP production33. Together, this provides more evidence that disrupted circadian rhythms may not only impact mitochondrial dynamics, but in some cases, may inhibit beneficial exercise-induced mitochondrial adaptations in the heart.

The present study found that a four-hour phase shift on weekends was sufficient to shift the activity onset of SJL mice, and that only SJL-EX returned to baseline activity onset time after four days. Our results are congruent with several studies that implemented simulated SJL, or other investigations of reentrainment following phase shifts in LD cycles. Circadian rhythms measured by PER2::LUC bioluminescence suggest that voluntary exercise shifts the circadian clock in the skeletal muscle, but not the SCN47. Leise et al. found that voluntary wheel running exercise accelerated harmonization of circadian clock genes and rhythms of behavior when aged mice underwent a LD phase advance48.

Exercise caused a more rapid reentrainment to baseline activity rhythms in the present study, as previously reported in other animal studies16,17. In human studies, exercise has also been demonstrated to attenuate negative effects of circadian rhythm disruption. Compared to normal sleepers (~7.5 h), sleep deprivation (~4 h) resulted in impaired glucose tolerance, mitochondrial respiratory function, and protein synthesis49,50. Sleep-deprived participants who completed high-intensity interval training, however, had no changes in glucose tolerance, mitochondrial respiratory function, or skeletal muscle protein synthesis49,50. Though it may be difficult for many people to completely prevent circadian rhythm disruption from SJL or sleep deprivation, exercise is clearly therapeutic in preventing many of the maladies stemming from circadian rhythm disruption.

The present study showed no significant changes in myocardial circadian clock genes in response to SJL or exercise. These findings are similar to Bruns et al., who demonstrated no significant changes in left ventricular Bmal1, Per2, or Clock in young, male mice after two weeks of free access to a running wheel and averaging ~10 km per day51. In the present study, SJL mice were sacrificed 48 h after their last shift. As such, it is possible that the myocardial circadian clock may have returned to baseline. In humans, circadian rhythms in heart rate and blood pressure are resynchronized within 48 h after LD cycle inversion52,53. In rats, clock gene oscillations in the heart may take up to eight days to resynchronize following a LD cycle reversal25. As our SJL intervention was only four hours, reentrainment of circadian clock genes may have occurred more quickly.

Another finding of this study was that there was no effect of SJL on protein expression for any of the OXPHOS complexes, and there was a very mild effect of exercise on Complex I. These findings are consistent with No and colleagues, who had rats perform forced treadmill exercise daily for 60 min36. No effects of exercise were observed for myocardial OXPHOS complexes of young mice, but found that exercise significantly increased complexes I, II, and IV in older mice when compared to sedentary older mice36. The lack of exercise-induced increases in mitochondrial content could be related to the relatively oxidative phenotype of the myocardium, which may require a more robust exercise stimulus to elicit mitochondrial biogenesis.

There were various limitations to the present study that should be considered. The study only included male mice. Thus, a sex difference analysis was not possible. In humans, SJL has been associated with worse sleep quality54 and cardiorespiratory fitness55 in males, but not in females. Future work should include biological sex as a variable. Additionally, food consumption was not monitored. Higher levels of SJL are associated with higher caloric intake and later meal times in humans56, though in mice a 6-h SJL intervention did not change caloric intake16. Another limitation is the timing of tissue collection. All animal sacrifices were performed at one time of day (~ZT5), not a 24-h time-course tissue collection. While tissue collection at a single time point allows for simple differences in circadian clock gene expression, it does not allow for analysis of clock gene expression rhythms.

In summary, SJL is an extremely common behavior that drives circadian rhythm disruption, affecting most of the modern adult population. These data provide evidence that exercise was a potential avenue for faster synchronization following circadian rhythm disruption like SJL. Furthermore, despite no changes in mitochondrial content or abundance, SJL inhibited exercise-induced increases in markers of mitochondrial fusion and fission. Circadian rhythms play a role in how the heart muscle adapts to exercise, as when these rhythms are chronically disrupted with SJL, mitochondrial dynamics in the heart are changed. Future studies should investigate how exercise timing and potentially different exercise modalities affect mitochondrial dynamics in the heart and other myocardial adaptations to exercise.

Responses