Solar-driven interfacial evaporation technologies for food, energy and water

Introduction

Many people lack secure access to food, energy and water (FEW), especially in rural areas or areas that lack centralized infrastructure and access to efficient distribution networks. In 2022, for instance, 1.3 billion people in rural areas lacked access to safely managed drinking water1. Technologies are needed that will alleviate FEW insecurities, but these technologies should be cost-effective and community-managed and they need to work off-grid to be effectively implemented.

Solar evaporation is a well-established method of evaporating seawater to obtain salt and fresh water2 without external energy inputs. This process can be sped up by floating a solar evaporator on the water’s surface to capture solar energy and localize this energy to evaporate water molecules3,4. This method, known as solar-driven interfacial evaporation, offers high solar-to-vapour efficiency independent of water volume3 and is adaptable to various applications5,6,7,8,9. After nearly a decade of research, this technology is approaching its thermodynamic efficiency limit of 92.5%5 and produces fresh water at a rate exceeding 80 l m–2 h–1 under concentrated sunlight10, operating stably for over 600 hours11.

Interfacial solar evaporation technologies have potential applications across the FEW nexus (Fig. 1). Potable water can be generated from various water sources (including seawater4, brackish water12 and industrial wastewater13) and the resulting water can be used domestically and in food production14. Wastewater — including domestic sewage15 and industrial wastewater from textiles16, thermal power plants13 and pharmacy manufacturing17 — can be treated with this technology, reaching zero liquid discharge13 (the complete separation of water and solutes). Hot vapour generation with solar evaporation can be used for disinfection and sterilization18,19. Moreover, interfacial solar evaporation can integrate with other renewable energy technologies to boost evaporation rates, electricity output and system efficiency, enhancing practicality and viability20.

Solar-driven interfacial evaporation technologies can use solar energy to treat wastewater and produce clean water, food, energy, minerals and chemical resources. These technologies can be used in rural and remote communities that lack access to water or energy infrastructure. Interfacial solar evaporation technologies include floating solar stills, which produce fresh water from seawater, and materials that are integrated into water-treatment plants. They can also be designed to produce fresh water for agriculture on land and on the ocean: the Farming On Ocean via Desalination (FOOD) system. Resources can be recovered from water by using interfacial solar evaporation to extract metals, such as lithium, or in combination with catalytic systems to produce hydrogen gas from water. Emerging designs integrate interfacial solar evaporation with renewable energy technologies like photovoltaic panels and wind turbines, enabling the simultaneous generation of electricity and other resources.

In this Review, we discuss interfacial solar evaporation innovations and design strategies in materials, devices and systems for water, food, energy, resources and wastewater treatment. We assess these technologies within the framework of production capabilities, suitability for low-resource settings, and key challenges for practical implementation. Last, we explore co-generation strategies and synergies with other technologies.

Water production and treatment

Interfacial solar evaporation efficiently separates water and solutes by localizing the solar heat at the liquid–vapour interface, transforming liquid water into vapour while leaving solutes behind6 (Fig. 2a). The resulting vapour can be condensed into drinking water or utilized in catalytic processes to produce hydrogen and other valuable chemicals. The solutes can be concentrated and precipitated, facilitating the extraction of valuable minerals like lithium and uranium. This section discusses water-centred applications of solar-driven interfacial evaporation, including clean water production, wastewater treatment and resource recovery from water, and efforts to enhance the performance and practical implementation of these technologies.

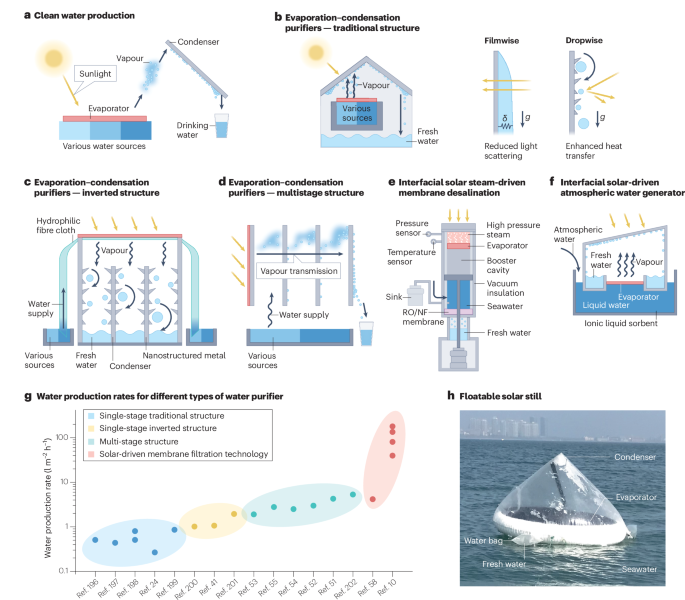

a, In interfacial solar evaporation, solar energy is absorbed by an evaporator, which warms and generates water vapour. The vapour condenses into water upon contact with the condenser. b, Traditional solar water generators use a transparent cover for condensation. Condensation can be enhanced by adjusting the surface hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity to promote filmwise condensation to avoid light scattering (left) and dropwise condensation for a high heat transfer coefficient (right). δ represents thermal resistance, g is gravity. c, Inverted-structure solar water purifiers decouple light absorption and condensation by placing the solar absorber above the condensation surface, shown here as hydrophobic condensers with rough structural designs. The water is drawn into the purifier through materials such as flexible hydrophilic fibre cloth. d, Multistage solar water generators have multiple hydrophilic water supply layers and condensation layers separated by air gaps to recycle the enthalpy of condensation. e, A solar steam-driven membrane technology for fresh water production uses solar energy to generate high-power steam, which generates the pressure to push saltwater through a reverse osmosis nanofiltration (RO/NF) membrane, producing clean water. f, Interfacial solar-driven atmospheric water generators use ionic liquids to harvest atmospheric moisture, which is then used in interfacial solar evaporation to produce clean water. g, Water production rates for different types of solar-driven interfacial evaporation technology (data from refs. 10,23,40,50,51,52,53,54,57,195,196,197,198,199,200,201 and detailed in Supplementary Table 1). h, A commercial floatable solar still. Panel d adapted with permission from ref. 50, RSC. Panel e adapted from ref. 10, Springer Nature Limited. Panel f adapted with permission from ref. 58, Wiley. Panel h photo credit: Weichao Xu.

Clean water production

Interfacial solar evaporation purifies water by condensing vapour from sources such as seawater, brackish water and industrial wastewater (Fig. 2a). The resulting distilled water consistently meets the World Health Organization’s ion concentration standards for drinking water3,21,22. This strategy has an estimated cost of US$0.4–2.2 per ton23,24,25,26,27, cheaper than small-scale reverse osmosis (US$5–10 per ton)28 and comparable to large-scale water purification systems (US$0.9–1.4 per ton)29. The decentralized nature of solar evaporation and its potential ability to provide high-quality water at low cost makes it a potential solution for drinking water in rural areas or islands8. There are various methods of producing clean water, including tandem evaporation and condensation, solar steam-driven membrane desalination and interfacial solar-driven atmospheric water generation, as discussed below.

Evaporation–condensation purifiers

Water purifiers that use a tandem solar evaporation and condensation strategy operate on the same fundamental principle (Fig. 2a), even when using different system designs. Solar evaporators made from materials with high solar absorptivity, such as carbon-based substances and plasmonic metals, capture and convert solar energy into heat through processes like electron excitation–relaxation30,31 and the localized surface plasmon resonance effect4,32. This localized heating at the evaporation interface accelerates the transition of water from liquid to vapour. The generated vapour diffuses towards the condensation surface, driven by the vapour pressure gradient. At the condensation interface, the vapour reaches a supersaturated, high-energy metastable state, leading to nucleation upon perturbation. The nucleated water droplets grow and coalesce, eventually reaching a critical size where they overcome surface tension and slide down under gravity, collecting as condensate water33,34. Advances in materials and device development have enabled evaporation efficiencies of over 90% under reduced optical concentrations35,36,37,38,39.

Condensation is the limiting factor in water productivity, because the evaporation rate often exceeds the condensation rate, resulting in insufficient vapour recovery40. Traditional solar purifiers use a single- or double-sloped transparent cover positioned above the evaporator. The cover allows sunlight to pass through while facilitating condensation when the vapour reaches saturation41,42 (Fig. 2b). Although easy to install, this structure has two limitations: the polymer or glass materials used for the cover typically have low thermal conductivity (<5 W m–1 K–1)40,43, leading to insufficient heat transfer and hindering condensation; and the condensed droplets exacerbate the thermal barrier and scatter sunlight, resulting in substantial light loss of up to 35%44.

To maximize water productivity, the condensation structure can be optimized and condensation efficiency can be enhanced45,46,47. For example, hydrophilic and/or hydrophobic modifications of the cover have been developed to enhance condensation48 (Fig. 2b). Hydrophilic covers promote filmwise condensation, reducing the light scattering caused by droplets. However, the water film formed on the cover has relatively low thermal conductivity (about 0.6 W m–1 K–1), which is detrimental to condensation49. By contrast, hydrophobic covers encourage dropwise condensation, with the heat transfer coefficient being 5–7 times higher than that of filmwise condensation34. Nevertheless, they suffer from substantial optical loss and potential durability issues.

Inverted-structure solar purifiers have been designed to overcome the limitations and enhance condensation40. The inverted structure places the condensation surface below the solar absorber, thereby decoupling the light absorption and condensation (Fig. 2c). As such, the condensation surface does not require high light transmittance45. The increased flexibility in material choice allows for the use of materials with high thermal conductivity and hydrophophic properties such as copper40 and aluminium (thermal conductivity of >400 W m–1 K–1)50 to enhance condensation. A 70% solar-to-clean-water efficiency has been achieved in the inverted condensation set-up40, compared with 20–50% in traditional set-ups.

Multistage solar water purifiers harvest and reuse the vaporization enthalpy by using multiple hydrophilic water supply layers and condensation layers separated by air gaps50,51,52,53,54 (Fig. 2d). This design recycles the latent heat released during condensation in one stage for evaporation in the next, enabling water production efficiency beyond the thermodynamic limit50,51. Optimizing the structure of a multistage still, such as the number of stages N and the thickness of the air gap tg, can further improve performance50,55. For instance, increasing N has produced a sixfold enhancement in water production rate compared with a single-stage device when N > 20 (ref. 50). However, water production and investment costs must be balanced when determining the number of stages, because overall efficiency does not increase linearly with N thanks to cumulative heat losses. Additionally, tg substantially affects water production. A small tg < 2.5 mm leads to strong heat conduction that decreases efficiency, whereas a large tg > 2.5 mm increases mass transport resistance, also limiting efficiency55. Therefore, quantitative analysis of heat and mass transfer and careful optimization of multistage device design are necessary50.

Steam-driven membrane desalination and beyond

Solar steam-driven membrane desalination uses high-temperature high-pressure steam generated by interfacial solar heating to push salty water through a reverse osmosis or nanofiltration membrane to produce clean water10 (Fig. 2e). Membrane desalination involves separating ions and water molecules using a selective membrane and requires much less energy than a single-stage solar evaporation–condensation purifier — the theoretical energy consumption for seawater desalination is 5.76 kJ kg–1, nearly three orders of magnitude lower than for the single-stage evaporation-condensation purifier, which is constrained by the vaporization enthalpy of water (about 2,400 kJ kg–1)56. Owing to the relatively low separation energy requirement, these membrane-desalination-based devices have reached rates of up to 81 l m² h–1 under 12-sun illumination10. This rate is higher than for single-still evaporation–condensation purifiers, which have a theoretical water production rate of 1.47 l m² h–1 under one-sun illumination5.

Thermal-responsive shrinking can drive water through a membrane by utilizing materials that undergo substantial shape or size changes in response to temperature variations, such as solar heating. This mechanism has been demonstrated in a solar-driven water purifier that combines a graphene nanofiltration membrane and poly(nisopropylacrylamide) (poly-NIPAM) with switchable hydrophilicity57. In this system, the purifier absorbs a large amount of water from a polluted water source. Upon photothermal heating, the absorbed water is released via the thermal-responsive hydrophilicity switching in poly-NIPAM (from hydrophilic to hydrophobic) while the outer graphene membrane effectively retains ions and molecules with a high rejection rate (>99%)57.

Integrating interfacial solar heating and atmospheric water harvesting allows direct generation of water from atmospheric moisture, further broadening the potential applications of both techniques58,59. This combination was demonstrated in an interfacial solar-driven atmospheric water generator that combined interfacial solar evaporators with an atmospheric water-harvesting sorbent based on ionic liquid58 (Fig. 2f). The system operates through a simultaneous adsorption–desorption process, and under outdoor conditions had a water production rate of 2.8 l m–2 per day in outdoor conditions58. In principle, this system can provide fresh water flexibly in areas that have an acute need for clean water but do not have a surface source of liquid water (like the ocean)60. However, improvements are needed, given that its water yield is typically lower than that of liquid-water-based processes61,62.

Application and the next generation

Clean-water production is an established application of interfacial solar evaporation with production rates of up to 81 l m–2 h–1 (ref. 10) under concentrated sunlight (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Table 1). Several simple and portable evaporation–condensation solar-powered water purifiers have advanced beyond the laboratory and are now commercially available (Fig. 2h). Once deployed, they float on water, absorb sunlight and convert it into heat, producing water vapour that condenses into purified water that is collected in a water bag attached to the device. These stills can reportedly produce approximately 2 l of water per day.

Advanced multistage50,51,52,53,54 and solar-membrane water purifiers10 have been evaluated at a scaled performance of 1 m2 and are capable of producing enough drinking water for an individual (3 l per person per day) and even meeting the basic clean-water needs for living (50 l per person per day). For example, a 10-stage device is expected to generate 36–60 l of clean water per day during the sunny summer months45. Solar steam-driven membrane desalination can produce over 600 l per day under 8–10 hours of 12-sun irradiation10. However, these systems are not yet commercially available. Scalability remains a challenge — they are effective at the laboratory scale (typically under 1 m²), but adapting them for larger communities or industrial use requires substantial technological refinement and infrastructure.

Although real-world application demonstrates the usefulness of this technology in clean-water production, further development and engineering are needed to address challenges such as the intermittent production caused by diurnal cycles, scale, stability and cost. The next generation of prototypes should aim to produce several litres of water per day to meet human daily needs. This scalability is feasible owing to the cost-effective and industrially mass-produced materials used in solar evaporation. Intermittent water production could be addressed through combining solar energy technologies like photovoltaic (PV) cells63 and phase-change materials64 to store energy during the day and use it at night for water purification, enabling continuous, all-day solar-powered water production.

Improving condenser performance is key to overall system performance, because the condenser typically contributes the most mass to the system. Indeed, the weight of the condenser is more than 40 times that of evaporator or sorbent65, greatly reducing the water yield per unit mass of the device. Strategies such as nanostructuring the surface of the condenser33,66 and implementing passive radiative cooling67,68,69 are expected to enhance the performance of the condenser. Nanostructuring creates micro- and nanoscale textures that promote the rapid coalescence of water vapour to liquid33. Passive radiative cooling lowers the surface temperature by emitting thermal radiation to the cold sky, creating a temperature gradient that accelerates condensation.

Active solar water generators, powered by electricity from solar energy, deliver higher water productivity than passive systems70. PV-driven reverse osmosis, a typical active system, converts solar energy into electricity via PV cells to drive the reserve osmosis membrane, producing clean water at a rate of 12–15 l m–2 h–1. These rates are an order of magnitude higher than those of most passive systems71. However, PV-driven reverse osmosis systems are heavier and larger owing to the additional PV modules.

Finally, most solar water generators are tested under stable indoor conditions with standard 1-sun illumination or in ideal outdoor conditions, such as sunny summer days or at noon9. These conditions are not realistic in terms of real-world operation, which has fluctuating solar illumination and substantial temperature variations. Therefore, the productivity and stability of upcoming solar water generators should be monitored and maintained over several months in the field. Factors such as water quality, especially organic matter content, must be tracked, as volatile organic compounds can evaporate with water, contaminating the distillate and compromising drinking water safety. Additionally, investment and maintenance costs must be thoroughly evaluated to assess the technology’s readiness for long-term field operation.

Wastewater treatment

Interfacial solar evaporation is being tested in the treatment of various types of wastewater, such as industrial wastewater, brines and domestic sewage21,72 (Fig. 3a). In this process, liquid water is continuously evaporated until only solids remain, achieving zero liquid discharge73. This approach mitigates the ecological threat of discharging highly concentrated brine and allows for the reuse of evaporated water by coupling a condenser, with the remaining solutes used for resource extraction.

a, Wastewater can be treated through interfacial solar evaporation, whereby solar energy heats an evaporator, generating clean-water vapour and leaving behind contaminants. b–d, Salts, microorganisms and organic matter can foul the evaporator, requiring mitigation strategies: Janus-design-based (panel b), Donnan-effect-based (panel c) and enhanced ion diffusion (panel d) evaporators can be used to reduce local salt concentration. e–h, Direct salt precipitation on the evaporator can be enabled through designing structures for salt rejection, such as a disc (panel e), cone (panel f), cup (panel g) or sphere (panel h). i, Spherical evaporators have been applied to a 25 m × 10 m wastewater treatment pond. j, Contactless evaporation is another strategy to confer salt resistance. k, Antimicrobial materials (such as silver, Ag, carbides and nitrides of transition metals, known as MXene, and reduced graphene oxide, rGO) can be added onto the evaporator to achieve anti-biofouling. l, Underwater superoleophobicity can be incorporated into the absorber for anti-oil-fouling. m–o, Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) can be removed through photocatalysis (panel m), size exclusion (panel n) and selective permeable membranes (panel o). CB, conduction band; e–, electron; Eg, band gap; h+, hole; hν, photon energy; VB, valence band. Part i is adapted from ref. 13, CC BY 4.0.

However, given that wastewater is a complex mixture that can contain high levels of salts, bacteria, oil and organic compounds, it can cause severe fouling on the solar evaporator. This fouling can block water flow and light absorption, leading to evaporator malfunction74,75,76,77. Therefore, developing evaporators with excellent operational stability, including resistance to salt, biofouling and organic contamination, is crucial for the successful application of interfacial solar evaporation in the treatment of wastewater.

Salt resistance

Salt resistance is essential for solar evaporators, because salt buildup is a common fouling issue in wastewater treatment9,78,79. When the rate of water evaporation exceeds the rate at which salt ions return to the bulk water, the local salt concentration increases rapidly, resulting in salt deposition on the evaporator. Strategies to enhance salt resistance can be grouped into three main approaches: reducing local salt concentration80,81,82,83, directing salt precipitation84 and implementing contactless evaporation22.

A Janus evaporator with dual hydrophilicity can reduce the salt concentration on its top surface, thereby preventing salt fouling80,85,86,87 (Fig. 3b). In this design, the upper surface is hydrophobic, acting as a protective barrier to prevent salt ions from reaching the evaporator’s top surface. The lower surface is hydrophilic, facilitating the back diffusion of salt ions into the bulk water and reducing the salt concentration within the evaporator. This approach is simple and feasible, using a common hydrophobic coating — fluorinated alkyl silane — which can be easily brushed onto the evaporator’s surface, and it maintained a stable water yield of 1.46 l m–2 h–1 for 15 days using seawater from the Yellow Sea85. However, ensuring the long-term stability of the hydrophobic and hydrophilic surfaces is a challenge. Prolonged exposure to sunlight and oxidative substances in water potentially degrades these functional surfaces, diminishing the performance of the evaporator88,89.

The Donnan effect can also be used to reduce salt concentration in solar evaporators83 (Fig. 3c). This approach uses a polyelectrolyte hydrogel evaporator with anions (such as COO−) fixed on its surface and cations (such as Na+) within to maintain electric neutrality. The confined Na+ ions establish a Donnan distribution equilibrium at the boundary between the evaporator and the surrounding brine, which reduces salt ion diffusion into the evaporator and minimizes local salt concentration. This approach supports stable evaporation of 1.3 l m–2 h–1 for 11 days with a 15 wt% NaCl solution83. However, the effectiveness of Donnan-effect-based salt resistance is reduced in high-salinity water with salinity greater than 150 g l–1 owing to the charge screening effect83.

Structural design can also be used to reduce salt concentration within the evaporator. For example, incorporating macroscopic water transport channels into the evaporator improves water convection, facilitating salt ions flow back to the bulk water and preventing salt buildup81,90 (Fig. 3d). However, this enhanced water convection also increases heat loss to the surrounding water, reducing evaporation efficiency to approximately 57% under 1-sun illumination. Therefore, several materials and structure designs have been developed to balance thermal localization and salt rejection91,92, such as enhancing conductive heat recovery93 and optimizing transport channel diameter94. Specifically, selecting an appropriate channel size induces natural convection, which speeds up salt rejection and minimizes heat loss, achieving an efficiency of 91%94.

Directing salt crystallization to specific areas of the evaporator and regularly removing it can enhance operational stability while maintaining high photothermal evaporation rates11,13. These salt crystallizers feature elaborately designed structures and shapes, such as disc11, cone84, cup74,95 and particle shapes13,76 (Fig. 3e–h). The disc evaporator11 uses a one-dimensional water uptake thread at the centre, creating a radial concentration gradient that directs salt crystallization to the edges (Fig. 3e). The disc design enables continuous, stable steam generation and salt harvesting for over 600 h with a 3.5 wt% NaCl solution11. Similarly, 3D cone evaporators form a water film with varying thickness and temperature gradients, causing salt crystallization at the apex, where the water film is thinner and hotter84 (Fig. 3f). This design achieves an evaporation rate of 2.63 l m–2 h–1 and an energy efficiency of over 96% with a 25 wt% NaCl solution84. Cup evaporators physically separate the water evaporation and the light absorption surface95 (Fig. 3g). The bottom and inner walls absorb solar energy and then transfer the heat to the outer wall, where evaporation and salt crystallization occur, achieving an evaporation rate of 2.42 l m–2 h–1 with 21.6 wt% brine95.

Manual74,95 and automatic13,42 methods can be used to remove salt crystals. For example, a dynamic and self-cleaning salt crystallizer has been developed as an automatic method13 (Fig. 3h). In this approach, a thin water film at the top (red spots in Fig. 3h) promotes preferential salt crystallization. As the salt crystals grow and disrupt the mechanical balance, the spherical crystallizer rotates, self-cleans and restarts the process. The surface tension causes these spherical crystallizer to act collectively, because the rotation of one crystallizer can induce correlative rotations of its nearby ones, leading to simultaneous self-cleaning of the whole system13. Of the crystallizer shapes discussed, spherical salt crystallizers are well suited for practical applications thanks to their self-cleaning ability and scalability. Over 100 m2 of crystallizers have been constructed and used to treat wastewater from coal-fired power plants, accelerating the concentration process13 (Fig. 3i).

Contactless evaporation is the most stable and effective salt-resistant strategy94,96, because it spatially separates the solar evaporator from the water (Fig. 3j). This approach requires an evaporator with asymmetric optical properties: the top surface needs high visible absorption and low infrared emission, whereas the bottom surface requires high infrared emission96. Such an evaporator can efficiently convert sunlight into thermal radiation, which is then emitted towards the wastewater and absorbed within a very thin layer (<100 μm) beneath the water–vapour interface, forming an interfacial evaporation structure22. This method offers long-term stability for high-salinity wastewater treatment and complete separation of solution and solute. However, owing to its non-contact nature, the photothermal conversion efficiency of contactless evaporation is limited to a maximum of 51%94, much lower than traditional contact-mode solar interfacial evaporation (>90%)6. Therefore, further improvements are needed to optimize heat and mass transport to improve solar utilization efficiency to make the contactless evaporation commercially viable. Higher efficiency would increase water yield and lower costs, making the process more competitive and sustainable for large-scale applications like desalination and wastewater treatment, where contact-mode systems face salt-fouling challenges.

Biofouling and organic contamination resistance

Solar evaporators are vulnerable to biofouling and organic contamination. For example, microorganisms and bacteria can adhere to the evaporator, forming biofilms that hinder water transport and light absorption, compromising operational stability97. A key strategy to combat biofouling is integrating antibacterial materials into the evaporator (Fig. 3k). Common antibacterial materials include inorganic nanomaterials like metallic nanoparticles98,99, reduced graphene oxide77,100, MXene101,102, and organic polymers such as chitosan103 and polyethyleneimine104. These materials act by disrupting cell walls101, denaturing bacterial proteins98 and/or generating reactive oxygen species103. Evaporators decorated with these antibacterial materials have demonstrated nearly 100% effectiveness against various bacteria, including Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus103,105.

Organic pollutants that are found in wastewater and affect evaporator performance include non-volatile organic compounds, such as oils, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs). High-viscosity oil contaminants in wastewater, for example, can clog pores and obstruct water flow in evaporators106. An effective way to prevent oil fouling is by creating superoleophobicity on the evaporator surface77,107 (Fig. 3l). Cassie contact induced by nanostructures can enhance surface oleophobicity, achieving a contact angle of 143° with soybean oil underwater77. This angle allows oil droplets to retain their spherical shape, thereby preventing them from sticking to and clogging the evaporator.

VOCs can evaporate together with water and pose health risks108,109,110, so physical and chemicals approaches are being developed for their removal from wastewater with solar evaporation109. Merging photocatalysis with interfacial solar evaporation is the most common chemical VOC removal approach (Fig. 3m). This method uses sunlight to excite photocatalysts to generate strong oxidizing •OH radicals that degrade VOCs into CO2 and other nonhazardous products111,112,113,114. For example, a reduced graphene oxide/polypyrrole aerogel has achieved an evaporation rate of 2.08 l m–2 h–1 and 94.8% VOC removal at 20 parts per million (ppm)115. However, photocatalysis becomes less effective at higher VOCs concentrations (<20 ppm), limiting its use to low-concentration wastewater116.

Physical methods, such as molecular sieving117 (Fig. 3n) and semipermeable membrane filtration77,110,118 (Fig. 3o) have been proved effective in removing higher concentrations of VOCs in condensate water during solar evaporation. Both methods allow water to pass through while blocking VOCs, but they rely on different mechanisms. Molecular sieving is based on the size-exclusion effect, whereas semipermeable membranes exploit different affinities of the membranes for water and VOCs. These physical methods effectively treat high-concentration VOCs (up to several hundred parts per million) with a retention rate of 99% at 400 ppm (ref. 117). A potential issue with physical VOCs removal methods is that they do not degrade the pollutants, which could lead to secondary pollution. In this regard, developing physicochemical strategies that combine the advantages of both physical and chemical approaches is essential to achieve the efficient degradation of high-concentration VOCs.

Application and the need for rigorous long-term testing

For use in the real world, with complex contaminants in wastewater, solar evaporators designed for wastewater treatment need to be resistant to fouling from many sources. Some progress has been made in this area, such as the development of a multi-effect anti-fouling evaporator that resists salt, bacteria, oil and VOCs. This evaporator features a graphene/alginate hydrogel evaporator with a dense internal structure and bio-inspired surface engineering77. Ion rejection (>99.3%) is achieved by creating a high osmotic pressure difference between the graphene/alginate hydrogel and contaminated surface water. The underwater anti-oil-fouling function is achieved through superoleophobicity (contact angle >140°) based on hydrophilic micro–nanostructure-induced Cassie contact. VOCs are removed (>99.5%) through the differential transport abilities of water and contaminant molecules in graphene/alginate hydrogel. Antibiotic properties are conferred by the exposed reduced graphene oxide nanosheets. The multiple anti-fouling mechanisms suggests that this graphene/alginate hydrogel can process wastewater with complex components into safe drinking water.

An important prerequisite for the commercialization of interfacial solar-driven wastewater treatment is a thorough assessment of stability over several months in real wastewater. Technology validations on simulated wastewater are acceptable, provided that these solutions mimic the physical, chemical and biological constituents of real wastewater. However, many studies primarily use sodium chloride solutions, which do not adequately represent real wastewater complexities. Difficult-to-remove salts, such as calcium sulfate, barium sulfate and silica, can form challenging scales; excluding these from simulations can lead to misleading results95.

Monitoring the performance and stability of wastewater evaporators in the field for several months is crucial to prove the technology’s long-term viability. Extended field testing allows evaluation under real environmental conditions, with variations in temperature, humidity and pollutant levels that can strongly affect performance. Additionally, long-term monitoring provides insights into system lifespan and maintenance needs. However, most reported field tests last less than 1 month. A minimum field test period of 6–12 months is recommended to assess performance stability, accounting for changes in weather and wastewater composition.

Resources from water

Resource extraction from water through interfacial solar evaporation is emerging as a way to meet the growing demand for resources such as critical metals119,120 and fuels121,122,123,124,125. For instance, valuable metals like lithium and uranium can be extracted from brines during evaporation and catalytic techniques like photocatalysis and electrolysis can be integrated with solar-driven interfacial evaporation to produce chemical fuels like hydrogen. This section describes resource recovery and generation using interfacial solar evaporation.

Critical metals

Interfacial solar evaporation can enable the selective extraction of critical metals (like lithium and uranium) from aqueous sources (such as seawater, salt lakes, and geothermal aquifers)119. However, the salinity of seawater and brines (35 to 400 g l–1) and the trace level of target resources in aqueous solutions (sometimes as low as parts per billion126) mean that these technologies must be salt-resistant and highly selective.

In one approach, interfacial solar evaporation has been combined with membrane technology to use the large, passively generated capillary pressures during interfacial solar evaporation to drive the membrane separation process, thereby eliminating the need for mechanical pumps119. For example, a solar transpiration-powered lithium extraction and storage (STLES) device comprising three functional layers has been developed for sustainable lithium recovery from brines119 (Fig. 4a). The top layer is a solar transpirational evaporator, acting as a green high-pressure (around 18 bar) and high-permeance (1.8 l m−2 h−1) pump. In the middle is a lithium storage layer, which conducts pressure and water between the evaporator and membrane and stores the extracted lithium salts. The bottom layer is a Li+-selective membrane, which allows Li+ to pass through and block other coexisting ions, like Ca2+ and Mg2+. The fabricated STLES operates through three main steps. First, solar transpiration creates a high capillary pressure within the evaporator. Next, this transpiration pressure is transmitted to the membrane, resulting in an influx of lithium from the brine to the lithium-storage layer. Finally, water circulation transports the extracted lithium to the reservoir and regenerates the device. The modular configuration allows scalable lithium extraction by combining multiple STLES units into an extended platform (Fig. 4a). For proof of concept, a 50 cm × 30 cm STLES platform was fabricated and successfully operated using solar energy to extract lithium from brines.

a, Solar transpiration-driven membrane separation (STLES) uses solar-driven transpiration to create a high capillary pressure within the evaporator. This pressure is transmitted to the selective membrane, causing an influx of brine lithium to the storage layer. Water circulation transports the extracted lithium to the reservoir and regenerates the device. b, An ion-selective evaporator selectively extracts resources such as lithium from aqueous sources. c, Spatially separated crystallization selectively extracts lithium from saline water. As water evaporates, salts with higher concentrations and lower solubilities (like NaCl) crystallize at lower heights of the fibre crystallizer. Salts with lower concentrations and higher solubilities (like LiCl) precipitate near the top. d, Prototype Li extraction array containing 10 × 10 three-dimensional spatial crystallizers. Salt crystals are seen on the blue cellulose fibre crystallizers. e, Photocatalysts embedded in interfacial evaporators catalyse the conversion of generated water vapour into hydrogen. Part a adapted with permission from ref. 119, AAAS. Part d adapted from ref. 136, Springer Nature Limited.

The evaporation-driven membrane filtration strategy is versatile and can be adapted for various applications by replacing the membrane127. For instance, capillary-powered desalination water bottles have been developed by combining solar evaporation with a reverse osmosis membrane128,129. These bottles, with a 9.4 cm diameter and a 10 cm wide annular fin, are capable of producing approximately 1 l of fresh water daily from seawater, thus facilitating water production in coastal regions.

Another strategy for extracting critical metals from water sources combines interfacial solar evaporation with selective adsorption130,131 (Fig. 4b). Interfacial solar evaporation offers two key benefits. First, it accelerates ion adsorption through enhanced diffusion and mass transport132; second, it boosts ion adsorption capacity because ion adsorption is typically endothermic, and increasing temperature shifts the equilibrium towards greater adsorption capacity, according to Le Chatelier’s principle133. This approach has been implemented in a Li+ sieve-integrated solar evaporator that was used for lithium recovery from a hypersaline salt lake131. Notably, both lithium capture capacity and adsorption kinetics are doubled thanks to the elevated temperature from the photothermal effect, which raises the temperature by 32 °C. Moreover, the produced fresh water is recycled for elution and Li+ sieve regeneration, achieving near-zero water and carbon footprint.

Similarly, various sorbents have been anchored to porous solar evaporators for selective metal recovery130,134. However, a potential limitation of this approach is stability — the sorbent particles are loosely attached to the evaporator and can fall off during operation135. An elegant solution is to directly functionalize the evaporator backbone. For instance, lithium-specific DNAzyme can be tethered to the polyacrylamide network via copolymerization, forming a stable DNA hydrogel for uranium extraction from natural seawater120.

Solar-driven interfacial evaporation is one of the few technologies that can completely dehydrate hypersaline solutions. By exploiting differences in solubility (different salts crystallize under distinct conditions or spatial locations), this process can selectively separate valuable metals from brines. For instance, string-based evaporators have been developed for harvesting lithium from saline water based on spatially separated crystallization136 (Fig. 4c). The string-based evaporators are made of porous, twisted cellulose fibres featuring a hydrophilic core and a hydrophobic exterior. When their ends are immersed in saltwater, the porous structure can raise water via the capillary action and allows for fast water evaporation on the side surfaces137. As water evaporates, salts with higher concentrations and lower solubilities, like sodium chloride, crystallize at lower heights of the fibre evaporator. By contrast, salts with lower concentrations and higher solubilities, like lithium chloride, move further upward and precipitate near the top (Fig. 4c). This spatially separated crystallization enables the collection of lithium and sodium individually, eliminating the need for additional chemicals. Another notable advantage of string-based evaporators is their scalability and adaptability. For example, a prototype array consisting of 100 string-based evaporators has been successfully demonstrated (Fig. 4d). However, further investigation is required to examine the effects of scaling up a treatment system that incorporates a larger number of strings. Potential drawbacks could include reduced vapour diffusion137.

Hydrogen

Merging interfacial solar evaporation with photocatalysis is being developed for the direct production of hydrogen from seawater121,122,123,124,125. The interfacial photothermal–photocatalysis approach offers three key benefits: the water vapour generated is inherently purified, eliminating the need for large-scale capital desalination plants and complex corrosion-resistant electrodes; the configuration of the liquid–vapour interface facilitates the rapid removal of evolved hydrogen (H2) and oxygen (O2) gases, promoting the catalysis reaction towards the desired product; and vapor-phase photocatalysis demands less energy for water splitting due to the lower standard Gibbs free energy of formation of gaseous water compared with liquid ((Delta {G}_{{text{H}}_{2}text{O}(text{g})}) = –228.6 kJ mol–1 versus (Delta {G}_{{text{H}}_{2}text{O}(text{l})}) = –237.2 kJ mol–1)138.

One interfacial photothermal–photocatalytic approach uses a biphase system, which is constructed by spin-coating photocatalytic cobalt oxide (CoO) nanoparticles onto carbonized wood slices123 (Fig. 4e). Under sunlight, the charred wood generates abundant water vapour via photothermal transpiration, which is then split into H2 by CoO. This photothermal–photocatalytic biphase system kinetically lowers the hydrogen gas’s transport resistance by nearly two orders of magnitude and thermodynamically reduces the interface barrier in the adsorption process of gas-phase water molecules to photocatalysts. As a result, the CoO–wood biphase system achieved a hydrogen production rate of up to 220.74 μmol h–1 cm–2, which is 17 times higher than that of CoO nanoparticles alone139.

Following the same principle as the biphase systems, hybrid photothermal–photocatalyst sheets have been developed for concurrent water purification and hydrogen generation from seawater121. The hydrophobically treated sheets can float on water, allowing for complete separation of the photocatalysts from the solution underneath. This separation prevents fouling of the photocatalysts, which would otherwise compromise their performance over time, thereby enhancing their stability and effectiveness. As a result, this design confers an operational stability exceeding 154 h in seawater and other aqueous waste streams.

Interfacial evaporation can also be integrated with PV electrolysis to generate hydrogen140. A prototype has been developed comprising a transparent cover, a PV cell and an electrolyser. The PV cells convert solar energy into electricity to power the electrolyser, which then uses this electricity for water splitting, producing H2 and O2. Importantly, the photothermal heating of the electrodes raises the local catalytic temperature, enhances convection above the catalyst surface for faster gas release, and enriches OH− near the catalyst surfaces, all of which boost catalytic performance140.

Scale and multi-product recovery are needed

Sustainable resource extraction through interfacial solar evaporation is interlinked with the concept of circular economy. Processing methods that allow for the simultaneous or sequential recovery of multiple products are needed to reduce the impact of resource extraction. For example, existing solar evaporitic technologies for lithium extraction from brines primarily focus on extracting lithium while discarding other valuable materials like the magnesium, potassium, calcium, sodium and boron present in the brines. To ensure sustainability and improve economic feasibility, future technologies should be designed for the joint recovery of two or more of these products.

Huge volumes of brine are processed at the industrial scale. For example, producing 20,000 tons of lithium carbonate requires the processing of approximately 7,668,254 m3 of a 700 ppm Li+ brine126. Interfacial solar evaporation techniques for resource recovery will need to scale appropriately to be applicable in the real world. Therefore, experiments conducted under elevated solar irradiations or within small-scale closed chambers are useful for research purposes, but are only a starting point, and larger demonstrations are needed.

Food production

Interfacial solar evaporation produces water that is suitable for agriculture, driving efforts to integrate interfacial solar desalination with agriculture. Interfacial solar desalination–agriculture systems could be particularly useful in coastal areas where fresh water and fertile soils are scarce. Coastal farming often relies on costly and energy-intensive desalination methods141,142, but solar evaporation systems passively desalinate water, making it more cost-effective143,144,145. Solar evaporation systems can wash saline or contaminated soils, thereby expanding arable land146. Finally, some of these systems can operate on the ocean, which reduces land use and is useful in space-constrained areas14. This section discusses interfacial solar evaporation applications in direct food production and soil remediation to increase land available for safe food production.

Farming on ocean via desalination

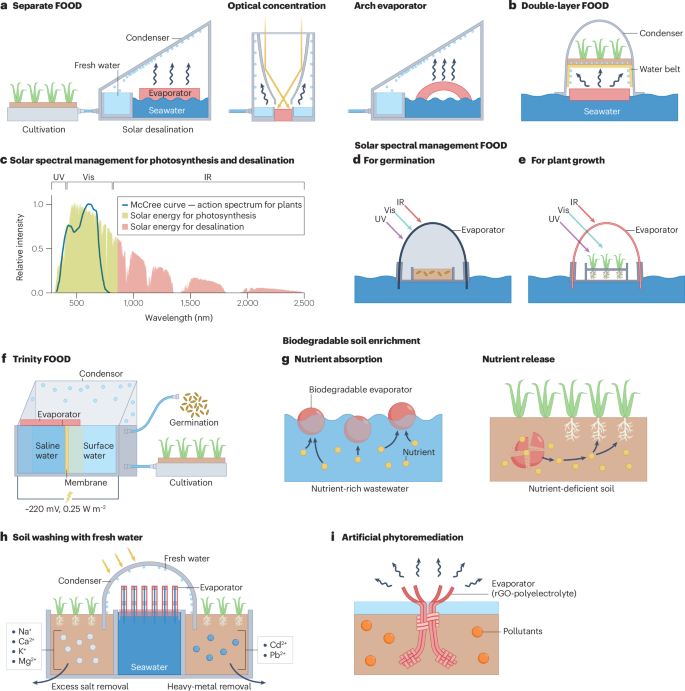

The Farming On Ocean via Desalination (FOOD) strategy integrates interfacial solar-driven seawater desalination with agriculture14. A FOOD system can have two separate chambers connected by a pipe to transport fresh water from the desalination chamber to the plant-growth chamber (the separate FOOD system in Fig. 5a). Desalination and agriculture can be independently optimized in this system, and strategies to enhance fresh water production could be implemented into the desalination unit. For instance, optical concentration of sunlight has been used to reduce the spatial requirements for solar evaporation (Fig. 5a), leaving more area available for agriculture147. Multistage distillation148, environment-enhanced evaporation146 and Marangoni-driven salt rejection149 (the arch evaporator in Fig. 5a) have also been used to improve the water production and long-term stability of the FOOD system.

a, Farming On the Ocean via Desalination (FOOD) system with two separate devices connected via a pipe to convey water from the desalination chamber to the cultivation chamber. Optical concentration and Marangoni-driven salt rejection (using an arch evaporator) can improve the system’s water production and long-term stability. b, The evaporator and cultivation area are stacked in double-layer vertical FOOD systems, which can sit directly on a saline water source. c, The action spectrum for plants (McCree curve, blue line) with the reference AM 1.5G spectrum. Desalination and photosynthesis use different spectra of sunlight, thereby improving the overall solar utilization efficiency by minimizing spectral overlap and maximizing energy conversion across processes. d,e, FOOD system based on solar spectral management with an external arched desalination chamber and an internal fan-shaped growth chamber. Tuning the evaporator can darken the interior of the chamber for germination (panel d) and allow ultraviolet (UV) and visible (Vis) light to pass through for plant growth (panel e). f, Integrated trinity FOOD systems desalinate water, generate power and irrigate crops. The system includes a desalination–power-generation chamber and a cultivation chamber. The energy of the salinity gradient between high-salinity seawater and surface water is extracted by the reverse electrodialysis technique to produce electricity. g, In solar-driven soil remediation, fresh water produced through interfacial solar evaporation is directly transferred into the soil, where it can be used for soil washing and/or agricultural irrigation. h, Biodegradable solar evaporators adsorb nutrients from wastewater and are transferred to soils, where they degrade and release nutrients. i, Artificial phytoremediation uses evaporators that are structured like plants. These evaporators use the solar interfacial process to accelerate the immobilization of pollutants in soil or water, enhancing remediation processes. IR, infrared; rGO, reduced graphene oxide. Part f adapted from ref. 153, Springer Nature Limited. Part h adapted with permission from ref. 146, Elsevier.

The installation of FOOD systems with separate desalination and agricultural chambers is straightforward, but the system has two fundamental drawbacks14. First, the physically separated operational units can use a substantial amount of land (even with optical concentrators), which can be problematic in land-constrained areas. Second, the overall efficieny of solar energy utilization is low because photosynthesis relies solely on visible light, which is only 51% of solar energy150,151. To overcome these limitations, vertical double-layer FOOD systems integrate solar desalination and plant cultivation on the same land152 (Fig. 5b). This design has two chambers, with agriculture in the upper chamber and fresh water production through interfacial solar desalination in the lower chamber. A water-transportation belt connects the two chambers and continuously supplies the desalinated water from the lower desalination chamber to the agricultural chamber. The vertical FOOD system uses space efficiently but lacks solar efficiency, because the upper agricultural chamber limits the sunlight reaching the lower desalination chamber.

Solar spectral management FOOD systems address space and energy utilization limitations by dividing solar energy into two components14. Shorter wavelengths (such as ultraviolet and visible light, about 300–800 nm) are used for plant growth and longer wavelengths (in the near-infrared, about 800–2,500 nm) are used for solar desalination (Fig. 5c). A key advantage of the solar spectral management FOOD system is that sunlight and fresh water are adjustable for different plants and growth stages. For instance, during the germination stage, seeds require abundant water but sunlight is unnecessary. A black dome, which absorbs the entire spectrum of sunlight (ultraviolet, visible and infrared), is installed and maximizes water production while completely blocking sunlight (Fig. 5d). During the plant growth stage, plants require both sunlight and water. Therefore, the black dome is replaced with a semi-transparent dome made of a selective photonic material that absorbs near-infrared light while allowing ultraviolet and visible light to pass through. This configuration enables ultraviolet and visible light to reach the plants for photosynthesis, while near-infrared light is absorbed by the outer cover for desalination (Fig. 5e). Consequently, this strategy optimizes both land and solar energy utilization efficiency.

Coupling other energy extraction technologies (such as salinity-gradient energy153, tidal energy154, thermoelectric energy155, and wave energy156) with the FOOD system can generate electricity in addition to food and fresh water, enhancing overall solar energy utilization. For example, a trinity FOOD system combining solar desalination, power generation and crop irrigation simultaneously produces fresh water, electric power and crop cultivation media using solar energy153 (Fig. 5f). Solar desalination increases the salinity of seawater from around 3.50 wt% to around 5.19 wt%, providing a continuous supply of high-salinity seawater. Energy is extracted from the salinity gradient between high-salinity seawater and surface water using reverse electrodialysis, generating a voltage of approximately 220 mV and a maximum power density of 0.25 W m–2. The fresh water produced from the solar desalination process (9.28 l m–2 per day) is centrally collected and supplied to the wheat cultivation section, which requires 6.0 l m–2 per day.

The floating cultivation farm based on interfacial solar evaporation leverages ocean and sunlight for agriculture, providing food in coastal regions. Crops such as wheat153 and vegetables such as lettuce148 and peas14 have been successfully cultivated via FOOD. To date, solar desalination–cultivation farms, as an emerging technology, have been mainly confined to laboratory-scale studies. Scaling these systems will require substantial engineering advances. The low condensation efficiency of passive devices poses challenges for improving water productivity, highlighting the need for enhanced condensation designs. Long-term practical studies are essential to evaluate the potential for bioaccumulation and the durability of devices in extreme weather events, such as cyclones.

To fully harness the potential of FOOD systems, further development and testing are required to produce food and achieve material circularity. Saline-tolerant, profitable species such as white-leg shrimp, Indian prawn, tilapia fish and milk fish could be farmed in the desalination pool. Nutrients and critical minerals can be extracted from the concentrated salts left from desalination. Moreover, agricultural waste, such as rice straw and corn cobs157,158,159, can be repurposed to construct solar evaporators, reducing material costs and minimizing waste generation. Solar pyrolysis can drive this process, converting by-products into eco-friendly, high-performance photothermal materials160. This circular approach enhances both sustainability and the economic viability of FOOD systems.

Soil remediation

Solar-driven interfacial evaporation can remediate contaminated soils through washing146, biodegradable soil enrichment161 and artificial phytoremediation162,163,164,165,166,167,168. The remediated soils can then be used for food production, after careful safety testing.

Soil washing with fresh water produced by interfacial solar desalination leaches contaminants such as excess salts, heavy metals and pesticides from the soil. Its exclusive use of free solar energy and applicability to various water resources (including seawater) makes it particularly well suited for coastal areas, where interfacial solar desalination can provide a steady supply of fresh water from seawater for both saline soil remediation and agricultural irrigation146. A typical set-up for interfacial solar fresh water leaching includes a seawater tank, an interfacial solar desalination chamber and a saline soil chamber (Fig. 5g). Sunlight transmits through the transparent cover and is absorbed and converted into heat by a photothermal evaporator. This heat facilitates seawater evaporation and the resulting vapour condenses into fresh water that drips down into the soil. Field tests demonstrate that this method removes hazardous contaminants at a rate three times faster than solar distillation, based on natural evaporation, completing the process in 16 days instead of 50 days146.

Soil quality deteriorates due to nutrient and microbial loss during soil washing, which is problematic when the treated soil is intended for agriculture169. Biodegradable solar evaporators (such as polysaccharide-based photothermal aerogel beads) are designed to mitigate these issues. They are initially used in wastewater remediation, where they adsorb nutrients from wastewater161. Once saturated, the beads are added to soil, where they slowly degrade and release the nutrients (such as phosphate, nitrate and potassium) (Fig. 5h).

Artificial phytoremediation absorbs, concentrates and removes contaminants (such as heavy metals) from soil163,164 by mimicking plant-based phytoremediation. Solar evaporators can be placed directly on contaminated soil to extract heavy-metal ions through transpiration163. Interfacial solar heating enhances evaporation to facilitate the migration of heavy metals from the soil into the evaporator along with water (Fig. 5i). As water evaporates, contaminants are concentrated and retained by the evaporators. Artificial phytoremediation is more efficient than plant-based phytoremediation and has several advantages165: effectiveness with high contamination levels; rapid contaminant absorption; and high contaminant-absorption capacity. In a trial addressing lead (Pb) contamination in soil, an artificial phytoremediation system used an evaporator equipped with Pb-binding agents, and was compared with a traditional plant-based phytoremediation using ryegrass163. After 2 weeks, the bioavailable Pb fractions in the soil decreased by 40% with artificial phytoremediation, compared with a 20% reduction with plant-based remediation.

Energy

Energy can be harvested from water evaporation through techniques such as thermoelectric, pyroelectric, salinity gradient and hydrovoltaic power generation (Fig. 6a). Interfacial solar evaporation can also be integrated with solar PV cells to enhance the performance of both technologies, allowing for joint production of clean water and electricity. Interfacial water–electricity co-generation is off-grid and decentralized, so it could provide an energy source for remote and rural areas that lack access to grid electricity. This section discusses methods of generating energy from interfacial solar evaporation and possible combinations with other energy-generation technologies.

a, Water evaporation can be harnessed to generate electricity by leveraging salinity gradients, thermal gradients and coupling with photovoltaic technology. b, Solar-driven interfacial evaporation of saline water creates a salinity gradient, and the diffusion of sodium ions (yellow dots) across the membrane generates electricity. c, Electricity is generated from directional ion diffusion driven by the salinity gradient. d, Thermoelectric methods can extract thermal energy from interfacial solar evaporation for electricity generation. e, Thermoelectrochemical methods extract energy through redox reactions driven by temperature gradients across an electrochemical cell. f, Pyroelectric methods extract energy by exploiting temperature fluctuations to induce electric polarization in pyroelectric materials, generating an electric current. g, Integrated tandem solar electricity–water generator. Thermalization heat generated in the photovoltaic (PV) cell is transferred to the water purifier through the thermal interconnecting layer, which enhances the water generation and cools down the PV cell. h, Electrical output and water purification rates for different types of solar-driven interfacial evaporation technology (Supplementary Table 2).

Salinity-gradient energy generation

Rapid water evaporation creates a salinity gradient between the high-salinity evaporation interface and the surrounding low-salinity solution. In interfacial solar evaporation systems, the energy density of the salinity gradient power can be higher than that of river–sea mixing and can be used for electricity generation170,171,172. For example, mixing evaporation-induced high-salinity brine (6 mol l–1) with seawater (0.6 mol l–1) yields about 12 kJ l–1, whereas mixing seawater (0.6 mol l–1) with river water (0.01 mol l–1) yields only 2 kJ l–1 (ref. 153). One system for solar evaporation and salinity power generation has an ion-selective membrane between the evaporator and seawater170 (Fig. 6b). Under solar irradiation, water evaporates quickly and creates a concentration difference between the solution beneath the evaporator and the bulk seawater. This gradient drives Na+ ions to diffuse through the membrane, generating 1 W m–2 of power and evaporating water at a rate of 1.15 l m–2 h–1.

Another approach uses a membrane to interface evaporated high-salinity brine with untreated low-salinity brine171 (Fig. 6c). An ionization electronegativity hydrogel is both the solar evaporator for daytime evaporation and the selective ion membrane for nighttime electricity generation. The system therefore produces either fresh water or electricity 24 hours of the day. Integrating evaporation and ion-selective functions into a single material reduces component complexity, potentially lowering operational costs. However, the need to switch modes between day (water generation) and night (energy generation) presents challenges in material design, mechanical durability and thermal management, requiring careful optimization for long-term performance.

Two considerations are key to advancing salinity-gradient energy generation. First, the current power output of about 1 W m–2 is far below the theoretical maximum of 12.5 W m–2 (ref. 170). Optimizing the ion-selective membrane’s properties, such as pore size, surface functionalization173 and selectivity, is expected to further enhance the output. Second, the high cost and complex fabrication of ion exchange membranes are a major barrier to widespread adoption. Ionized wood membranes could be more cost-effective for this application174. A wooden membrane (1.2 m × 1 m × 1 mm) costs about US$10, compared with US$350 for commercial membranes175. However, the relatively large thickness of wood membranes could constrain the power and energy density of wood-based salinity energy generators, as performance typically scales inversely with membrane thickness174.

Thermal-gradient energy generation

Thermal energy from interfacial solar evaporation can be extracted and converted to electricity through thermoelectric176,177,178, thermoelectrochemical179,180, and pyroelectric41,181,182 methods. Thermoelectric methods generate electricity by using a temperature difference across a thermoelectric module, which operates via the Seebeck effect183. In this set-up, one side of the thermoelectric module (Bi2Te3) is connected to the heated part of a solar evaporation system, such as hot vapour177 or the evaporator176, while the other side is kept in contact with a cooler area, like ambient air or surrounding water (Fig. 6d). This temperature gradient across the module creates a voltage, which can be used to power external devices or stored in batteries. This approach has generated power outputs of 292.9 W m–2 under 30-sun irradiation and 63 mW m–2 under 1-sun irradiation177.

Thermoelectrochemical approaches exploit the temperature-dependent electrochemical redox potentials to generate energy184 (Fig. 6e). A typical thermoelectrochemical cell has two identical electrodes, a redox couple electrolyte, and an external connection. Applying a thermal gradient induces oxidation at the anode and reduction at the cathode, with reduced species diffusing back to the anode to sustain continuous reaction and current flow185. For example, these cells have been applied to harvest the latent heat released from vapour condensation, with a maximum power output of 6.94 mW m–2 under natural solar irradiation179. Compared with thermoelectric methods, thermoelectrochemical cells are more cost-effective but typically have lower power densities.

Unlike thermoelectric and thermoelectrochemical devices, pyroelectric devices do not require a spatial temperature gradient. Instead, they convert temporal temperature fluctuations into electricity186 (Fig. 6f). This conversion is achieved by integrating a composite film of tungsten-doped vanadium dioxide (W-doped VO2) and polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) into the interfacial solar evaporation system182. Upon sunlight exposure, the W-doped VO2 undergoes a phase transition that alters its solar-to-heat conversion and generates temperature oscillations. These temperature fluctuations activate the PVDF layer, producing continuous electrical output. The system exhibited self-adaptive temperature oscillations up to 7 °C, with a maximum electrical power density of 104 μW m–2 (ref. 182).

Solar-driven interfacial evaporation has an abundant dynamic flow of water, vapour and ions. Therefore, evaporation-induced kinetic energy can be converted into electrical energy by utilizing streaming potential — the voltage difference created by fluid movement through a porous medium. For instance, the evaporation-induced directional flow of seawater through ionic channels in a porous evaporator can generate a stable potential of 117.8 mV (ref. 187). The evaporation of pure water vapour from nanostructured carbon surfaces can produce voltages of up to 1 V, sustained for over 300 hours188.

Water–electricity co-generation

Coupling PV with interfacial solar evaporation can improve the PV panel’s performance, enhance the overall utilization efficiency of solar irradiance, and simultaneously produce electricity and clean water189,190 (Fig. 6g). The set-up comprises three components that work synergistically: a PV cell at the top to generate electricity, a thermal interconnecting layer in the middle to transfer the thermalization heat from the PV cell to the water purifier, and an interfacial solar water purifier at the bottom to generate clean water189. The solar panels can be up to 11 °C cooler by evaporation from the purifier below, enabling an increase in electricity generation of up to 7.9% relative to the PV system without the purifier189. The heat from the PV cells is transferred to the water purifier to purify water at a rate of 0.80 l m–2 h–1 under natural sunlight. The tandem system also maximizes photon utilization. The top PV cells use above-bandgap photons while the bottom purifier uses below-bandgap photons, representing an overall solar energy utilization efficiency of 74.6%189. The water-production rate can be further increased through a PV-multistage distillation device, in which the latent heat released during vapour condensation is recycled53,54. A three-stage version of this system has a water production rate of 1.64 l m–2 h–1 (ref. 54), while a five-stage system produces 2.35–2.45 l m–2 h–1 of fresh water from seawater (ref. 53).

Application and viability

The demonstration of four types of water–electricity co-generation technique highlights the viability of solar-driven interfacial evaporation technologies for decentralized electricity generation (Fig. 6h and Supplementary Table 2). Hybrid systems that combine interfacial solar evaporation with thermal, salinity or hydrovoltaic energy-harvesting techniques are lightweight and cost-effective, and off-grid solutions can generate 1–10 W m–2 of electricity. These technologies are suitable for small-scale, distributed, low-energy applications such as Internet of Things devices and sensors. For example, the evaporation-induced hydrovoltaic device is sensitive to ambient wind speed, which can be utilized to construct wind-speed sensors191.

Solar PV–desalination hybrid systems are better suited for larger-scale implementation, as these systems have reached up to 204 W m–2 for electricity189 and 2.5 l m–2 h–1 for water53 in separate systems. A roof-sized PV-desalination hybrid system can produce the daily drinking water and energy needs of a household, defined here as a family of four with average consumption of 50–60 l of drinking water per day and 10–12 kWh of electricity.

Power generation through interfacial solar evaporation is technologically immature, with opportunity for material and system development. For example, we could envision a dual-function strategy that combines solar-driven interfacial evaporation with hydrovoltaic technology192 to achieve simultaneous resource recovery and power generation. In this dual-function system, solar evaporation utilizes solar energy to evaporate water, concentrating valuable minerals and salts for easier extraction, while hydrovoltaic technology converts the kinetic energy of water movement into electrical energy.

Comprehensive assessment and optimization of evaporative power generation technologies are needed to maximize their efficiency and address potential challenges. For instance, although pairing interfacial evaporation with solar cells results in higher efficiency for both PV and desalination, there are still uncertainties regarding the technology’s technical and economic aspects193. The potential biofouling of panels by microbial biofilms could pose a greater problem over water than on land and could decrease PV output194.

Summary and future perspectives

Solar-driven interfacial evaporation technologies use solar energy to treat or desalinate water, extract resources, aid food production and/or produce power. They can function off-grid, making them potentially suited to addressing FEW demands in rural areas with limited infrastructure. Advances in materials, devices and systems have improved the efficiency, productivity and stability of the systems. However, in most cases, FEW resources are produced individually, reducing energy and space efficiency while increasing costs. Co-generation strategies that can produce FEW resources simultaneously within a unified system need to be prioritized to maximize energy efficiency and deliver collective benefits, such as lower cost, better space efficiency, and improved availability and stability (Box 1).

Because different solar technologies rely on different parts of the solar spectrum, efficient solar energy management is key to maximizing energy utilization and engineering interfacial solar evaporation systems for co-generation. Solar radiation spans approximately 200 to 2,400 nm, with 47% of its total energy in the visible (380–780 nm), 51% in the infrared (780–2,500 nm), and the remaining 2% in the ultraviolet parts of the spectrum (Box 1). Interfacial solar evaporation can harness almost the entire solar spectrum, but PV converts sunlight into electricity primarily within the visible (380–780 nm) and near-infrared (780–1,100 nm) ranges (Box 1). Photosynthesis operates in much narrower bands, specifically 400–500 nm and 600–700 nm (refs. 150,151). Engineering co-generation systems that independently harness different parts of the spectrum, working synergistically, would enable usage of nearly the entire spectrum.

Serial transduction is also important to boosting overall output, as it captures energy intermediates (Box 1). For instance, the kinetic and internal energy of hot vapour, often discarded as waste, can be recovered by recycling the heat released during condensation50. Pairing the photothermal evaporator with radiative cooling to create thermal gradients can generate electricity through thermoelectric systems.

From these principles, we propose strategies for FEW co-generation with high energy efficiency and outputs, including syngas–water co-generation, heat–water co-generation and electricity–water co-generation with cooling, heating, water or biochar (Box 1). Developing these systems will require integrating advanced materials, optimizing heat and mass transfer, precisely controlling energy flows and synchronizing various techniques. Ultimately, it is essential to monitor the long-term productivity and stability of these systems in real-world conditions. Moreover, we strongly recommend comprehensive life-cycle assessments to evaluate environmental impacts before implementation to guide application and more efficient and sustainable use. Finally, advances in hardware design and mass production will be crucial to reducing costs and making these technologies widely accessible, ensuring global access to FEW solutions.

Responses