Solid base-assisted photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene via the Norrish mechanism through the generation of alternating polyketones

Introduction

Polyethylene is a polymer obtained by the polymerization of ethylene monomers [1]. As the most ubiquitous plastic material, polyethylene is known for its nontoxic nature and chemical stability. Therefore, polyethylene is widely used in various applications, such as in the manufacturing of thin films, containers, pipes, wires, cables, etc. [2]. However, owing to its inert hydrocarbon chains, polyethylene is resistant to natural degradation in the environment. According to a 2018 United Nations report [3], the annual consumption of polyethylene products is five hundred billion, and the majority of these products are eventually discarded without proper treatment, leading to severe environmental issues.

With the growing global emphasis on environmental protection, traditional plastic waste disposal methods, such as incineration and landfilling, are increasingly considered unsustainable, as they release toxic substances and exacerbate environmental issues [4, 5]. Consequently, in recent years, numerous environmentally friendly plastic recycling methods have been proposed, including thermo-oxidative degradation, biodegradation, mechanical degradation, and photocatalytic degradation [6,7,8,9]. Among these methods, photocatalytic degradation is considered a promising approach because of its mild operating conditions, low energy consumption, pollution-free nature, and simple process [10,11,12].

In the field of photocatalytic degradation, TiO2 is a highly favorable photocatalyst, primarily due to its excellent redox capability under UV exposure, chemical stability, cost-effectiveness, and environmental friendliness [13, 14]. Nonetheless, its tendency to aggregate, the large band gap (~3.2 eV), and the rapid recombination of photoexcited electron-hole pairs limit the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of TiO2 [15,16,17]. Many studies have been devoted to overcoming the limitations mentioned above to improve the degradation efficiency of TiO2. Wenyao Liang et al. recently showed that grafting polyacrylamide onto TiO2 can increase the dispersibility and hydrophilicity of TiO2 in polyethylene, allowing TiO2 to adsorb moisture and generate more({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) to attack C‒C chains [18]. As reported by Shenyang Li et al., by using sol-gel and emulsion polymerization methods to prepare polypyrene (PPy)/TiO2 nanocomposites as photocatalysts, electrons, and holes can be effectively separated at the interface between PPy and TiO2 to improve the degradation efficiency of polyethylene [19]. However, the complex catalyst preparation process reduces the applicability of these methods.

According to the proposed photocatalytic degradation mechanisms, photoexcited holes readily react with ({{mbox{OH}}}^{-}) to generate a large amount of ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) radicals [20], which are the primary species responsible for the mass loss of polyethylene [21, 22]. To increase the efficiency of TiO2 in the photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene, in this study, polyethylene degradation by TiO2 under alkaline conditions was first examined. The FTIR results indicate that, in an alkaline environment, TiO2 induces the formation of alternating polyketone (APK) structures, which present a greater density of ketone groups than isolated carbonyl groups on C–C bonds. These two types of ketone groups were introduced by Baur et al. [23]. Under identical polymer lengths, polymers with alternating polyketone (APK) structures inherently contain a higher density of ketone groups than those with isolated carbonyl (IC) structures. Since photocatalytic degradation involves the decomposition of C=O bonds through a Norrish type I reaction, leading to mass loss [24], the formation of APK groups within the polyethylene structure can effectively increase the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of polyethylene.

A non-toxic and low-cost solid base, K2CO3, was employed after confirming the effects of the catalyst under alkaline conditions in the above photocatalytic degradation system, which was combined with TiO2 to prepare LDPE and HDPE composite films through simple processes, including blending and hot pressing. Additionally, the structures of LDPE and HDPE also generated APK functional groups under TiO2 and K2CO3 catalysis, leading to enhanced photocatalytic degradation efficiency.

Materials and methods

Materials

Commercial low-density polyethylene powder (LDPE) (Sigma‒Aldrich; molecular mass (MM) = 35,000; Mn: ~7000; ρ = 0.906 g/cm3; particle size < 400 µm) and commercial high-density polyethylene powder (HDPE) (Formosa Plastics Group; MM = 120,000; ρ = 0.920 g/cm3; particle size < 100 µm) were used as representatives of plastic waste. TiO2 nanoparticles (99.5%; Sigma‒Aldrich; MM = 79.87 g/mol; ρ = 4.23 g/cm3; particle size = 21 nm) were used as the photocatalyst. Potassium carbonate (K2CO3) (98%; Sigma‒Aldrich; MM = 138.21 g/mol; ρ = 2.43 g/cm3; particle size = 325 mesh) and NaOH (98%; Uniregion Bio-Tech; MM = 40 g/mol; ρ = 2.13 g/cm3) were applied as additives.

To prepare the PE composite films via drop casting and to verify the absorption wavelength of the PE samples via UV‒Vis spectroscopy, cyclohexane (99.9%; Alfa Aesar; MM = 84.16 g/mol; ρ = 0.779 g/cm3) was used to dissolve the LDPE powder.

Preparation of PE composite films

Hot pressing

LDPE films were prepared by adding 0.5 g of LDPE powder to 20 ml glass vials. For the LDPE/TiO2 composite films, 0.5 g of LDPE powder was mixed with TiO2 (1, 5, or 10 wt% LDPE powder) and manually shaken for 30 s. Similarly, LDPE/TiO2/K2CO3 composite films were prepared by adding K2CO3 (3 wt% LDPE powder) to the LDPE/TiO₂ (1, 5, and 10 wt% LDPE powder) mixture and shaking for the same duration. The raw materials were then sequentially placed in a hot press (LFT-1503-01, Ling Fong Technology Co. Ltd., Taiwan), preheated at 90 °C for 1 min, and then hot pressed for 1 min to produce LDPE films and LDPE composite films (150 µm).

The same process was applied to produce HDPE films (0.5 g HDPE powder) and HDPE/TiO2/K2CO3 composite films (0.5 g HDPE powder, 1 wt% TiO2, and 3 wt% K2CO3), with the only difference being an increase in the hot-pressing temperature to 120 °C.

Drop casting

LDPE films and LDPE/TiO2 composite films were prepared by dissolving LDPE (0.5 g) and adding TiO2 (1 wt% LDPE powder) in cyclohexane (50 ml) at 70 °C under stirring for 1 h. Then, the solution was ultrasonicated (15 min) to obtain a uniform dispersion of TiO2 powder. The LDPE-TiO2 solution was spread on a Petri dish (ID = 3 cm), and the solvent was evaporated at 70 °C on a hot plate for 30 min. The films were subsequently incubated at room temperature for 48 h to remove the remaining solvent (thickness = 40 μm). After LDPE-TiO2 composite films were prepared via drop casting, a 5 M NaOH solution was added to the Petri dishes to test the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of the LDPE‒1T composite films under alkaline conditions.

Photocatalytic degradation and characterization of composite films

The composite films were placed in a UV crosslinker (35 × 27 × 16 cm) at room temperature. UV light was emitted from six eight-watt lamps (λ = 254 nm; intensity = 5 mW cm−2). The cut films (4 × 4 cm) were placed 16 cm away from lamps. The degradation performances of the films were obtained by calculating their mass loss following Eq. 1 (Mb: mass before irradiation; Ma: mass after irradiation). Each set of mass loss data was measured four times, and the average value was calculated. The data are presented as the mean mass loss with the standard error.

To compare the degree of oxidation in the film before and after irradiation, attenuated total reflection-Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) (PerkinElmer, Spectrum Two) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used to analyze the functional groups on the films. The surface morphology and elemental composition of all the samples were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JEOL JSM-6460) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS).

A tensile test (Universal Testing Machine, EZ-XS, max capacity 500 N) was used to determine the mechanical properties of the films before irradiation, and the mechanical properties were determined via Eqs. (2 and 3).

To verify the thermal properties of the films, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, TA Instruments TA 550) was used to test their decomposition temperatures (Td), and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC, TA Discovery DSC-25) was used to determine the melting point (Tm). Additionally, to ensure that the mechanical properties of all the samples were consistent under extreme conditions from −20 to 80 °C, dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA Q800 – TA Instruments) was performed.

Verification of photocatalytic degradation mechanisms

Scavenger

To confirm the influence of ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}), ({{mbox{h}}}^{+}), ({{{rm{e}}}}^{-}), and ({{mbox{O}}}_{2}^{,bullet -}) free radicals on the photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene by TiO2, corresponding free radical scavengers were utilized in this study to capture the free radicals generated during the photocatalytic reaction. The scavenger solutions used for ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}), ({{mbox{h}}}^{+}), ({{{rm{e}}}}^{-}), and ({{mbox{O}}}_{2}^{,bullet -}) were 0.1 M tertiary butyl alcohol (99%; Tedia; MM = 74.12 g/mol; ρ = 0.789 g/cm3), 0.25 M isopropyl alcohol (99.5%; Duksan; MM = 60.10 g/mol; ρ = 0.782 g/cm3), 5 × 10−4 M ammonium persulfate (98%; Showa Kako India; MM = 60.10 g/mol; ρ = 0.782 g/cm3), and 10−3 M p-benzoquinone (98%; Alfa Aesar; MM = 228.19 g/mol; ρ = 1.98 g/cm3), respectively [25, 26]. These free radical scavengers were separately added to polyethylene samples, and their inhibitory effects on photocatalytic degradation were tested to determine the influence of free radicals on the photocatalytic degradation reaction.

Fluorescence technique

The concentration of ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) generated during the photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene samples was determined via a fluorescence technique (ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy: U-4100 UV/VIS/NIR spectrophotometer, Hitachi; and spectrofluorometry: Fluorolog-3 spectrofluorometer, HORIBA Jobin Yvon). The reaction between terephthalic acid and ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) rapidly generates 2-hydroxy terephthalic acid, which exhibits significant fluorescence properties. In this study, the samples were immersed in a solution containing terephthalic acid (5 × 10−4 M) dissolved in NaOH (2 × 10−3 M) and exposed to UV light to generate 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid. After being excited (λ = 315 nm), 2-hydroxyphthalic acid emits light (λ = 425 nm). The fluorescence intensity of 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid is directly proportional to the concentration of ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) [27].

UV/VIS/NIR spectroscopy was employed to assess the oxidation level of the samples. Specifically, 5 mg each of LDPE, LDPE-5T, and LDPE-5T-3K samples were dissolved in 4 mL of cyclohexane on a hot plate at 70 °C. The mixture was then left undisturbed for 2 h to allow the LDPE to dissolve in cyclohexane and enable the precipitation of TiO2/K2CO3. After this period, the supernatant was collected for analysis.

Results and discussion

Photocatalytic degradation of LDPE by TiO2 under alkaline conditions

To determine the optimal TiO2 ratio in LDPE films, TiO2 was added at ratios of 1, 5, and 10 wt%. and the degradation performances were evaluated under UV irradiation. Figure S1a shows that the degradation efficiency increased as the TiO2 addition ratio increased. Compared with pure LDPE (mass loss of 24.14%), the LDPE-5T composite film and the LDPE-10T composite film strongly improved the degradation efficiency (mass loss of 41.15% and 42.45%, respectively). Although the latter exhibited the highest degradation efficiency, the amount of TiO2 used was two times greater than that of the former, and the degradation efficiency increased by only 1.3%. As shown in Fig. S1b, the mechanical properties of the pure LDPE film and the LDPE/TiO2 composite films were assessed. The LDPE-10T composite film exhibited the lowest tensile strength and strain among the samples. Figure S1c shows the surface morphology of the pure LDPE film and LDPE/TiO2 composite films before irradiation. The TiO2 particles exhibited severe aggregation in the LDPE-10T composite film, which significantly reduced the efficiency of the catalyst. As shown in Fig. S1a–c, the optimal TiO2 ratio was less than 5 wt%.

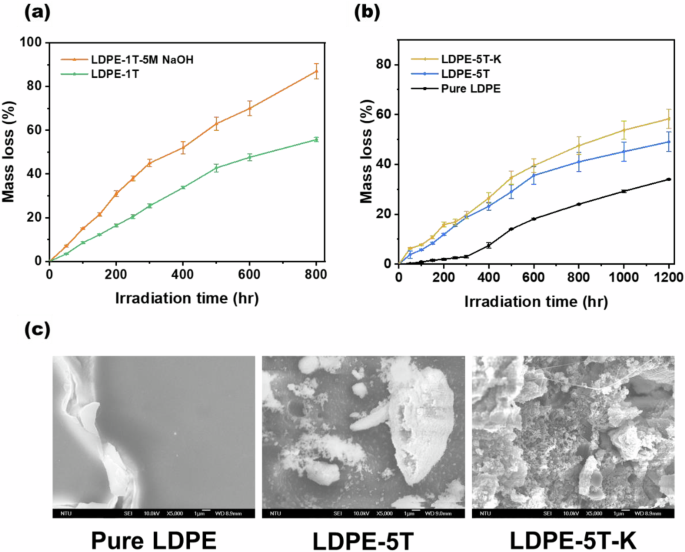

Figure 1a shows that after 800 h of UV irradiation, the degradation efficiency of the LDPE-1T composite film soaked in a 5 M NaOH solution reached 87%, whereas the degradation efficiency of the LDPE-1T composite film was only 55.72%. These findings suggest that the TiO2 photocatalytic degradation system is effective at degrading polyethylene under alkaline conditions. However, to simplify the process, the method of film production for the samples in Fig. 1b was changed from drop-casting to hot pressing. Because the thickness of commercial polyethylene bags is generally less than 100 μm [28, 29], the thickness of the film samples was increased from 40 to 150 µm to increase the applicability of this study. The mass loss performances are shown in Fig. 1b, where the LDPE-5T-K composite film displayed a degradation efficiency of 58.30% after 1200 h of UV irradiation and the LDPE-5T composite film showed a degradation efficiency of 49.05%. These findings indicate that the solid base K2CO3 can increase the degradation efficiency of polyethylene.

a Mass loss curves of LDPE composite films with a thickness of 40 µm under UV light irradiation (film samples were prepared by drop casting). b Mass loss curves of LDPE films with a thickness of 150 µm under UV light irradiation (film samples were prepared by hot pressing). c SEM images of pure LDPE film, LDPE-5T composite film, and LDPE-5T-K composite film after 600 h of irradiation

As shown in Fig. 1c, the morphology of the LDPE film after 600 h of irradiation was analyzed via SEM. Compared with the pure LDPE film and the LDPE-5T composite film, the LDPE-5T-K composite film presented only minor cracks and shallow structural damage, whereas the LDPE-5T-K composite film presented the most severe structural damage and deep fractures. The above results show that under alkaline conditions, the degradation efficiency of the LDPE film sample improved. The optimal ratio for TiO2 combined with K2CO3 in PE was determined, and the results in Fig. S1d show that after 400 h of irradiation, the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of the LDPE-5T-K sample was greater than that of the LDPE-10T-K sample. As observed in the SEM images in Fig. S1e, the aggregation of TiO2/K2CO3 was evident in the LDPE-10T-K composite film before UV irradiation, which significantly affected the photocatalytic performance of TiO2. Therefore, regardless of whether K2CO3 is added, keeping the TiO2 content in PE below 5 wt% is optimal.

Characterization of LDPE composite films under UV irradiation and alkaline conditions

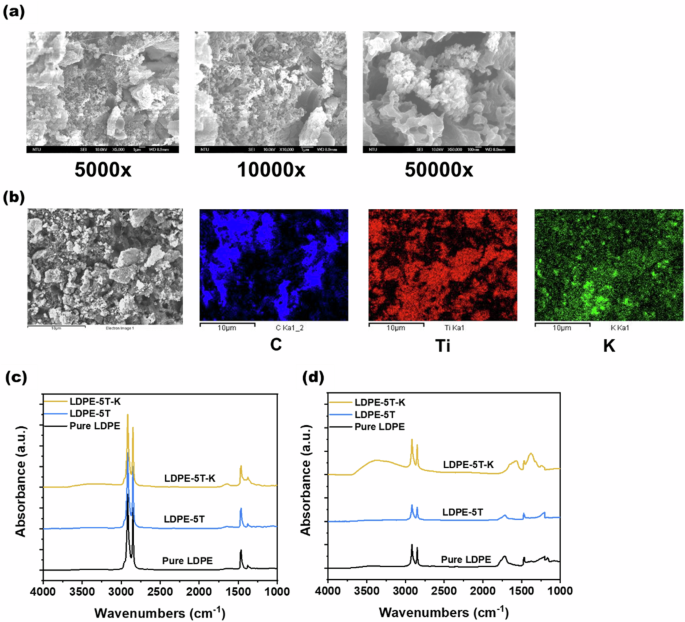

As shown in Fig. 2a, SEM images of the LDPE-5T-K composite film were taken at magnifications of 5000x, 10,000x, and 50,000x. Significant amounts of TiO2 and K2CO3 particles were observed within the ruptures, indicating that TiO2 and K2CO3 can effectively degrade the polyethylene film under UV light irradiation. To confirm the presence of the particles in the ruptures of the LDPE-5T-K composite film, SEM-EDS was conducted. Figure S2 shows the presence of several elements in the LDPE-5T-K composite film: carbon (C) from polyethylene, oxygen (O) from TiO2 and polyethylene oxidation, titanium (Ti) from TiO2, and potassium (K) from K2CO3. Furthermore, SEM-EDS elemental mapping analysis was performed to examine the distribution of these elements on the film samples. The results shown in Fig. 2b indicate that carbon (C) is sparsely distributed, whereas titanium (Ti) and potassium (K) are abundant. These findings suggest that TiO2 and K2CO3 effectively degrade the polyethylene film.

a 5000x, 10000x, and 50000x SEM zoomed-in images of the LDPE-5T-K composite film after 600 h of UV light irradiation. b SEM-EDS elemental mapping analysis of the LDPE-5T-K composite film after 600 h of UV light irradiation. c Before UV irradiation and (d) after 600 h of UV irradiation, ATR-FTIR spectra of pure LDPE film, LDPE-5T composite film, and LDPE-5T-K composite film

To compare the functional group changes in the pure LDPE, LDPE-5T, and LDPE-5T-K samples before and after UV light exposure, the characteristic peaks of the samples before UV irradiation are shown in Fig. 2c and Table S1. C-H stretching vibrations in the PE chain occurred at 2925 and 2850 cm−1, and C‒H bending vibrations occurred at 1465 and 1380 cm−1 [30]. The samples also showed O-H bending at 1649 cm−1 due to the intrinsic hydrophilicity of TiO2. In addition, the LDPE-5T-K composite film presented a relatively strong O‒H bending characteristic peak because K2CO3 is prone to deliquescence [31, 32]. The characteristic peaks of the samples after 600 h of UV irradiation are shown in Fig. 2d and Table S2. The characteristic C-H stretching vibration peaks were at 2925 and 2850 cm−1, and the characteristic C-H bending vibrations were at 1465 and 1380 cm−1 in the PE chain. Furthermore, a characteristic peak of the isolated carbonyl group was found at 1715 cm−1 in the spectra of the pure LDPE film and LDPE-5T composite film. In addition, the LDPE-5T-K composite film presented an alternating polyketone group at 1650 cm−1 [23].

The alternating polyketones and O‒H bending functional groups had the same peak at 1650 cm−1. To determine the source of the peak at 1650 cm−1, other characteristic peaks of the LDPE-5T-K composite film after exposure to UV were analyzed. The O-H stretching characteristic peaks at 3555 and 3340 cm−1 were attributed to hydroperoxide products [33] and oligomeric alcohols [34]. C=C stretching was also detected at 1595 cm−1 [35]. The above functional groups are generated after the samples produced ketone groups and underwent Norrish reactions to degrade PE [36, 37]. Notably, as shown in Fig. 2d, the LDPE-5T-K composite film exhibited stronger characteristic peaks of C=C stretching and O‒H stretching than the other samples did. These results suggest that alternating polyketones were produced in the LDPE/TiO2 composite film under alkaline conditions after exposure to UV light, increasing the content of carbonyl groups in the PE chain, which led to easier degradation. Thus, the addition of K2CO3 is effective in performing the Norrish reaction to degrade PE.

Figure S3 confirms the thermal properties of the pure LDPE film, LDPE-5T composite film, and LDPE-5T-K composite film before irradiation. Thermal gravimetric analysis was performed by heating the samples from 50 to 550 °C, and the thermal decomposition temperature (Td) of polyethylene was found to be in the range of 310–325 °C. Differential scanning calorimetry was conducted by heating the samples from 50 to 150 °C, and the melting point (Tm) of polyethylene was determined to be in the range of 95–97 °C. Dynamic mechanical property analysis was carried out by heating the samples from −20 to 100 °C, and the storage modulus and loss modulus of the test samples were measured. The above results indicate that there were slight changes in the thermal properties of the LDPE-5T composite film and LDPE-5T-K composite film compared with those of the pure LDPE film. This suggests that the photocatalytic degradation strategy in this study is beneficial for practical application in commercial polyethylene products.

Photocatalytic degradation of HDPE by TiO2 under alkaline conditions

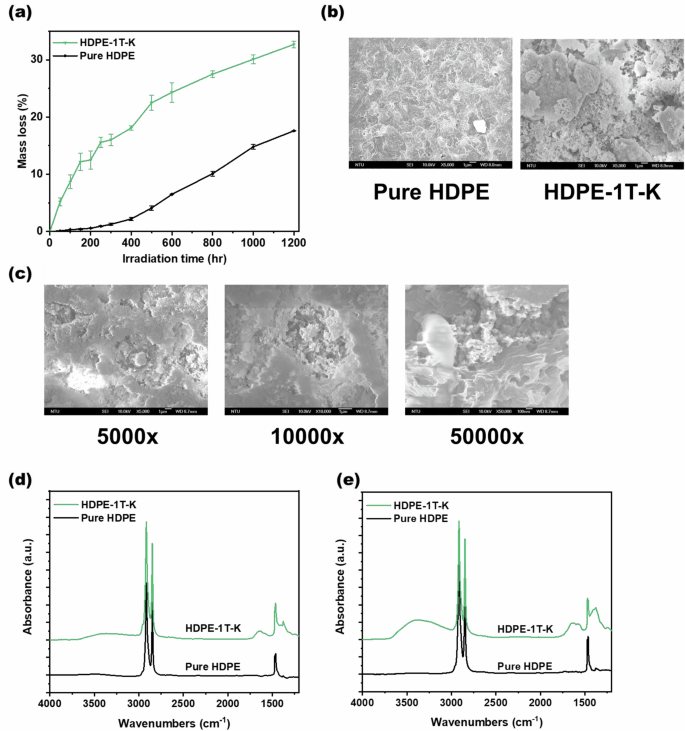

Figure 3a reveals that the addition of TiO2 and K2CO3 to HDPE films can enhance photocatalytic degradation efficiency. After 1200 h of UV light irradiation, the HDPE-1T-K composite film exhibited a mass loss of 32.7%, whereas the mass loss was 17.6% for the pure HDPE film. As shown in Fig. 3b, after 600 h of irradiation, the surface of the pure HDPE film exhibited minimal cracking. However, the HDPE-1T-K composite film was severely damaged. Figure 3c shows zoomed-in images of the most severely damaged area of the HDPE-1T-K composite film. Significant amounts of TiO2 and K2CO3 particles were observed within the ruptures.

a Mass loss of HDPE film with a thickness of 150 µm: pure HDPE film and HDPE-1T-K composite film were prepared by hot pressing under UV light irradiation. b SEM images of the pure HDPE film and HDPE-1T-K composite film after 600 h of irradiation. c 5000x, 10000x and 50000x SEM zoomed-in images of the HDPE-1T-K composite film after 600 h of UV light irradiation. d Before UV irradiation and (e) after 600 h of UV irradiation, ATR-FTIR spectra of the pure HDPE film and HDPE-1T-K composite film

Figure S4 shows the results of the elemental analysis of the HDPE-1T-K composite film via SEM-EDS. Carbon (C), oxygen (O), titanium (Ti), and potassium (K) were detected in the film sample. It was observed that areas with a relatively high distribution of carbon had relatively low distributions of titanium and potassium. The changes in the functional groups of the pure HDPE and HDPE-1T-K samples before and after UV light exposure are also shown in Fig. 3d, e. After 600 h of irradiation, alternating polyketones (1650 cm−1), O–H stretching (3555 and 3340 cm−1), and C=C stretching (1595 cm−1) were observed in the HDPE-1T-K sample, showing the same results as those of the LDPE-5T-K sample. After UV light irradiation, the HDPE-1T-K composite film was analyzed for mass loss, surface morphology, and functional group formation.

Owing to the negative correlation between photocatalytic degradation efficiency and film thickness, no significant trend was observed in relation to the molecular mass [38,39,40,41]. LDPE-1T-5M NaOH demonstrated the highest photocatalytic degradation efficiency among the LDPE samples listed in Table 1, even with a thicker film. Additionally, in this study, no complex catalyst modifications were required, and samples were prepared through simple blending and hot pressing techniques. Finally, HDPE can also be used in this photocatalytic degradation system, significantly broadening the applicability of this research.

Verification of the photocatalytic degradation mechanism

According to the photocatalytic degradation mechanism, TiO₂ particles are excited under UV irradiation, producing photoexcited e− and h⁺ (Eq. 4) [14, 42]. These photoexcited electrons then react with O2 to form superoxide radicals (({{mbox{O}}}_{2}^{,bullet -})), which oxidize H2O to generate hydroxide ions ({left(right.{mbox{OH}}}^{-}) and hydroperoxyl radicals (({}^{bullet }{mbox{HO}}_{2})) (Eqs. 5, 6) [14, 43]. Furthermore, hydroperoxyl radicals self-react to produce hydroxyl peroxide (H2O2) and O2 (Eq. 7) [43]. When H2O2 absorbs UV light energy, hydroxyl radicals(({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}})), which are important species in the photocatalytic degradation mechanism, are generated (Eq. 8) [44]. In this study, hydroxide ions from NaOH and K2CO3 were used to increase the photocatalytic degradation efficiency of polyethylene through reactions with h+, producing ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}), which also came from water (Eqs. 9–13) [20, 45,46,47,48].

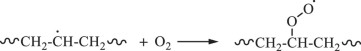

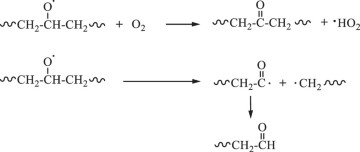

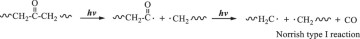

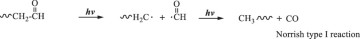

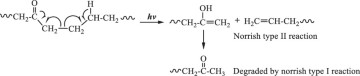

Then, hydroxyl radicals serve as initiators of the degradation process by oxidizing the C‒C chains of polyethylene. (Eq. 14). In the presence of atmospheric oxygen, the oxidized C‒C chains rapidly form peroxy radicals (({{{rm{ROO}}}}^{bullet })), which propagate with other polymer chains (RH) to generate hydroperoxide (ROOH) (Eqs. 15, 16) [22, 49, 50]. Once hydroperoxide (ROOH) is formed, it decomposes into an alkoxy radical (({{{rm{RO}}}}^{bullet })) and a hydroxyl radical (({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}})) under light irradiation because of its weak O‒O bond (Eq. 17) [51]. Owing to their instability, alkoxy radicals facilitate the formation of polymers containing ketone and aldehyde groups through reactions with O2 and β-scission (Eq. 18) [52,53,54,55,56,57]. Upon subsequent UV irradiation, these ketone and aldehyde groups undergo Norrish type I and II reactions. Norrish type I involves α-cleavage, which degrades the polymer into CO and causes mass loss (Eqs. 19, 20) [58, 59], whereas the Norrish type II reaction involves α,β-carbon–carbon bond cleavage, forming carbonyl and vinyl groups (Eq. 21) [60]. In this study, the proposed mechanisms require both Norrish type I and II reactions (Eqs. 19–21) to achieve mass loss, which is considered the rate-determining step.

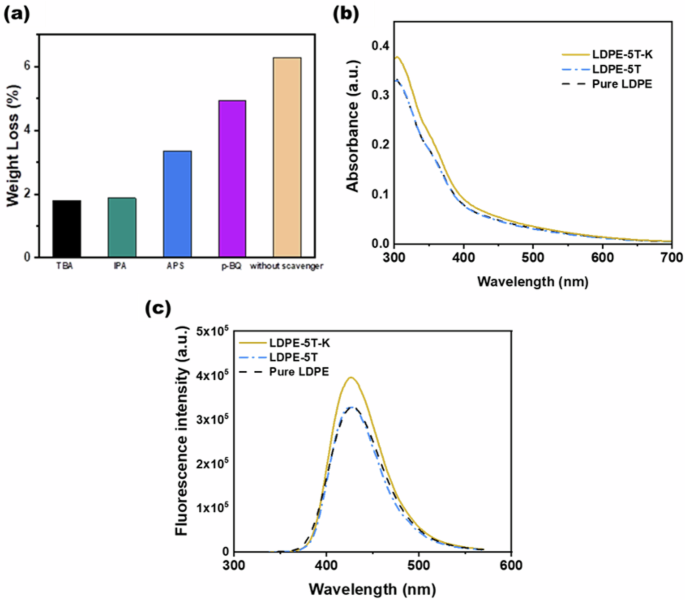

During TiO2 photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene, various free radicals, such as electrons (({{{rm{e}}}}^{-})), holes (({{mbox{h}}}^{+})), superoxide radicals (({{mbox{O}}}_{2}^{,bullet -})), and hydroxyl radicals (({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}})), are generated. To clarify the influence of these free radicals on the photocatalytic degradation of polyethylene, different free radical scavengers were utilized in this study to capture specific free radicals generated during the photocatalytic degradation process. By reducing the concentration of these free radicals in the reaction mixture, the degradation efficiency of the LDPE-5T-K composite film was evaluated. In this case, tertiary butyl alcohol (TBA), isopropyl alcohol (IPA), ammonium persulfate (APS), and p-benzoquinone (p-BQ) were used to scavenge ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}), ({{mbox{h}}}^{+}), ({{{rm{e}}}}^{-}), and ({{mbox{O}}}_{2}^{,bullet -}), respectively. Figure 4a shows the effects of different scavengers on the photocatalytic degradation of the LDPE-5T-K composite film. TBA and IPA, as scavengers for ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) and ({{mbox{h}}}^{+}), were added to the LDPE-5T-K composite film, followed by 50 h of UV light exposure. The mass losses were 1.8% and 1.88%, respectively. APS and p-BQ, which act as scavengers for ({{{rm{e}}}}^{-}) and ({{mbox{O}}}_{2}^{,bullet -}), exhibited mass losses of 3.35% and 4.93%, respectively. Without a scavenger, the mass loss of the sample was 6.29%. The above results show that the concentration of ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) in the photocatalytic degradation system determines the efficiency of photocatalytic degradation.

a Effects of different scavengers on the degradation efficiency of the LDPE-5T-K composite film after 50 h of UV irradiation. b UV‒Vis absorption spectra of LDPE film samples immersed in 2 × 10−3 M NaOH solution containing 5 × 10−4 M terephthalic acid after 2 h of UV irradiation. c Fluorescence spectral changes observed (excitation at 315 nm) during illumination of LDPE film samples after 2 h of UV irradiation

In the proposed photocatalytic degradation mechanism, hydroxyl radical (({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}})) generation primarily occurs via water adsorption by the base, followed by dissociation into ({{mbox{OH}}}^{-}) and subsequent reaction with holes (Eqs. 9–12), rather than through photolysis of hydrogen peroxide (Eq. 8) or the reaction of water with holes (Eq. 13). Therefore, there are two approaches to verify the contributions of the reactions shown in Eqs. 6–8: Eqs. 9–12 and Eq. 13. The result of the p-BQ scavenger (({{mbox{O}}}_{2}^{,bullet -})) experiment indicates that ({{mbox{O}}}_{2}^{,bullet -}), which directly affects the generation of hydrogen peroxide (Eqs. 6–8), has a relatively minor effect on the degradation of polyethylene. However, when APS (({{{rm{e}}}}^{-})) was used as a scavenger, it inhibited the photocatalytic degradation reaction. Owing to the acidic nature of the APS solution, it underwent an acid-base neutralization reaction with ({{mbox{OH}}}^{-}), thereby inhibiting the generation of ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) (Eq. 12). Figure S5a compares the mass loss of pure LDPE films, LDPE/TiO2 composite films with and without water immersion, and LDPE/TiO2/K₂CO3 composite films under UV light irradiation. The results show that both pure LDPE and LDPE/TiO2, regardless of water immersion, have a limited impact on photocatalytic degradation. In contrast, the addition of K2CO3 to the samples significantly enhanced the photocatalytic degradation effect. These findings confirm that the ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) generated in this photocatalytic degradation system originates from the reactions in Eqs. 9–12 rather than those in Eqs. 6–8 and Eq. 13.

On the basis of the above results, the dissociation of ({{mbox{OH}}}^{-}) from a solid base can effectively generate ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}), and capturing ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) and ({{mbox{h}}}^{+}) in the TiO2 photocatalytic degradation system can significantly inhibit the occurrence of photocatalytic degradation reactions. The results in Fig. 4a demonstrate that ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) is the key free radical in the degradation of polyethylene. To verify the concentration of ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) in the TiO2 photocatalytic degradation system, a fluorescence technique was used to measure the amount of ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) generated. Figure 4b shows the UV‒vis absorption spectra, revealing that the terephthalic acid solution exhibited the strongest absorption at a wavelength of 315 nm. Hence, 315 nm was selected as the excitation wavelength for photoluminescence (PL) testing. The fluorescence emission spectrum of the terephthalic acid solution excited at 315 nm was measured. Figure 4c shows the fluorescence induced from soaking pure LDPE, LDPE-5T, and LDPE-5T-K films in 5 × 10−4 M terephthalic acid in 2 × 10−3 M NaOH solution, followed by 2 h of UV light exposure. The results indicated that the LDPE-5T-K composite film presented the strongest light intensity at a wavelength of 425 nm.

To further confirm that combination of TiO2 with alkali effectively generates C=O and enhances photocatalytic degradation efficiency (Eqs. 19–21), UV‒Vis spectroscopy was used to determine the concentration of C=O. Figure S5b shows that the absorption peak of the LDPE-5T-K sample in the 250–310 nm range is stronger than those of the LDPE and LDPE-5T samples. Specifically, the 250–280 nm range corresponds to the signals of C=O and C=C, whereas the 280–310 nm range corresponds exclusively to the C=O signal [61]. The XPS results, as shown in Fig. S5c, indicate that the LDPE-5T-K sample exhibits strong signals at binding energies of 528–531 eV, 530–532 eV, and 532–535 eV, which are attributed to the O=C-OH, C-O, and C=O functional groups, respectively [62,63,64,65,66]. Both tests are consistent with the results shown in Fig. 2d.

Furthermore, FTIR analyses of LDPE and HDPE samples under different irradiation times (100, 200, and 300 h) are shown in Fig. S5d. The results indicate that, compared with LDPE, HDPE has slightly lower peak intensities for carbonyl signals (1715 cm−1 for isolated carbonyls and 1650 cm−1 for alternating polyketones), alcohol signals, and hydroperoxide signals (3555 and 3340 cm−1), which vary with irradiation time. This variation suggests that these three functional groups are formed through irradiation (Eqs. 14–18) and that the C=O groups are subsequently consumed by the Norrish I reaction (Eqs. 19–21). Consequently, HDPE exhibited only a 17% mass loss after 800 h of irradiation (Fig. 3a).

Conclusion

The mass loss, surface morphology, and mechanical property results in this study first confirm that the optimal ratio of TiO2 in polyethylene films is less than 5%. Alkaline conditions were subsequently induced using NaOH to assess the efficiency of polyethylene degradation in the TiO2 photocatalytic system. The experimental results revealed that after 800 h of UV light exposure, the LDPE-1T composite film soaked in a 5 M NaOH solution exhibited a mass loss of 87%. In comparison, the mass loss of the unsoaked sample was 55.72%, demonstrating the feasibility of this photocatalytic degradation strategy.

To simplify the sample preparation process, the film fabrication method was changed from drop-casting to hot pressing, and the thickness of the film was increased from 40 to 150 μm to increase the applicability of this study. The experimental results demonstrated that the mass loss of the LDPE-5T-K composite film was 58.30% after 1200 h of light exposure. In comparison, the mass loss of samples without the addition of K2CO3 was 49.05%. Furthermore, analysis of functional groups via FTIR spectroscopy indicated that under alkaline conditions, polyethylene undergoes photocatalytic degradation with TiO2 to produce alternating polyketone structures that are conducive to photocatalytic degradation, whereas samples without the alkaline additive only exhibited isolated carbonyl formation.

Additionally, through the use of scavengers, it was confirmed that ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) is the most important free radical in this photocatalytic degradation system. Moreover, PL analysis confirmed that the addition of a solid base to the TiO2 photocatalytic degradation system effectively increased the concentration of ({}^{bullet }{{rm{OH}}}) radicals. These radicals subsequently generated C=O groups on the PE chain, leading to mass loss through the Norrish I reaction. Finally, by applying this photocatalytic degradation strategy to HDPE, the degradation efficiency of HDPE can also be improved.

Supplementary Information

The supporting information is available from the Springer Nature Library or from the author. Mass loss curves, tensile strength and strain curves, and SEM images of LDPE samples with varying ratios of TiO2. Functional group analysis, SEM-EDX images, and thermal property analysis of PE samples.

Responses