Space Analogs and Behavioral Health Performance Research review and recommendations checklist from ESA Topical Team

Introduction

As the human-robotic Artemis lunar exploration program is about to be implemented and space agencies start planning for crewed missions to Mars, the assessment of psychological factors is becoming increasingly relevant to human spaceflight. Future space missions will feature new challenges that emerge in a multidisciplinary and multicultural workspace.

The performance of the space crews is subject to various factors, such as national, organizational, and professional cultures, as well as team dynamics and individual attributes, like personality and physical condition, technical infrastructure, procedures, natural risks, and operating environments1,2,3,4,5. These factors are key to mission performance and safety, ultimately determining mission outcomes. In-depth analysis is vital to ensure the success of human spaceflight missions in terms of individual health, work satisfaction, and crew morale. Closely related to these factors is the study of the brain and more specifically its cognitive, behavioral, and emotional correlates. Behavior in general and cognitive functioning in particular depends on the proper functioning of the brain, and, therefore, it is important to analyse the possible effects of space and the specific interactions and physical conditions of crewed space missions.

Since the early Apollo-era, analog studies have supported the preparation of planetary surface missions (e.g., ref. 6) as an effective and efficient tool, also to prepare for future missions to Mars. Mars analogs on Earth are used to understand human aspects related to exploration of the Red Planet from the scientific point of view (e.g., refs. 7,8) to optimize operational workflows9 and test field equipment and human factors in a representative environment10. Such past analog campaigns include initiatives like the NASA D-RATS field simulations conducted between 1997 and 201011,12, confinement studies conducted by the European Space Agency (ESA) and RSA, including ISEMSI, EXEMSI, HUBES, SFINCSS, and MARS500, the NASA HI-SEAS long-duration missions13,14, the MOONWALK project15, the NASA NEEMO underwater missions, the AMADEE field campaign series10, the ESA CAVES missions16, the polar station Concordia17, the NASA BASALT mission18, and others.

In summary, a variety of setups and scenarios exist today where we can study aspects of behavioral health performance and psychosocial interaction. This investigation will inform future space missions, especially the long-term missions bringing humans back to the Moon, Mars, and beyond. However, it may be challenging to determine which scenario or analog environment is better suited to study certain types of problems, whether they are cognitive, emotional, operational, or social behavioral in nature.

In the present study, a group of experts from an ESA-funded research topical team initiative reviewed the current situation of the topic, potentialities, gaps, and recommendations for appropriate behavioral health, psychological aspects, and performance research in space analogs. This paper is a review about the current state of space analogs on Earth and future perspectives on behavioral health and performance research aspects in these environments, including a classification and matrix system to help determine not only the main characteristics of each available space analog, but also the best focus for every research topic target. Although possible synergies with the study of physiological variables and the effects of gravity are mentioned, these were not the fundamental focus of this study.

Space analogs and simulations

One can distinguish between space analogs and simulations by the fact that simulations are pre-planned to recreate or project a specific space mission, with all stages clearly determined a priori, including length, overall achievements, and objectives. Mars 500 is an excellent example of this type of space mission simulation. We can use simulations to test some methods and systems, although experimental conditions can be quite different. This may be one of the reasons why we still have limited evidence from space studies that shows negative effects of spaceflight19. Space analogs may arise incidentally from other human activities in isolated and/or confined environments, such as during Antarctic expeditions, or they may be planned to simulate complex interactions of environmental, physical, physiological, and social aspects during space missions20.

Analog environments offer specific characteristics that resemble to some extent the environment of a real space mission. These analog environments are suitable platforms to study adaptation mechanisms to extreme environments, since in many cases these analog environments involve challenging and certain living conditions similar to those experienced by astronauts during space missions, including isolation, reduced space, limited equipment infrastructure, extreme physical environments, and others. An important reason for research in space analogs is the limited opportunities to collect data from astronauts during actual spaceflights. Also, there are several advantages of using analog environments. For example, they allow for larger sample sizes than those typically available during spaceflight missions. In addition, subjects are less restricted and can dedicate more time to scientific experiments. Analog environments are also more efficient, not only economically, but they also allow for a more specific focus on single areas of scientific interest. These analog environments are especially interesting from the psychological point of view since they allow the investigation of mental and social variables in very similar conditions to those occurring during real space missions. Finally, analog environments offer enhanced flexibility to set up simulated missions of different durations, from days to months, to simulate adverse weather conditions, and to simulate emergency situations19 (Fig. 1).

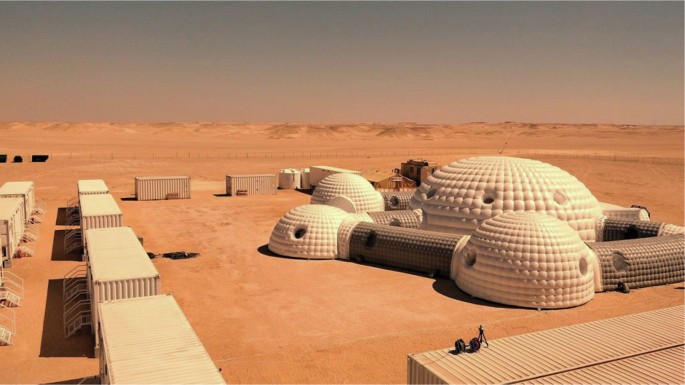

AMADEE space analog mission in Oman, 2018 by AUSTRIAN SPACE FORUM (OEWF). Image credit: OEWF.

Analog missions also represent an opportunity to test operational approaches and conditions to gather information on combinations of processes and team dynamics most optimal for completing specific aspects of missions. Considering that the exploration of planetary surfaces is challenging and difficult due to the extensive planning, resource mobilization, and technological development required, analog missions on Earth provide invaluable scientific potential for innovation and preparation.

Studies in analog settings have provided opportunities to evaluate the effectiveness of methods of monitoring psychological and interpersonal aspects that have later been useful in real flight situations21. Sandal et al.22 found that time patterns in psychological reactions differed between analogs, specifically between polar expeditions and crews confined in hyperbaric chambers. The authors concluded that the relevance of different analogs may depend on mission characteristics. Space analogs have included Antarctic stations and remote deserts, subsurface and underwater facilities, and also expeditions. An important distinction between analog environments and simulations is that analog environments are locations where human missions would take place with certain goals, regardless of space research. For example, military submarines and Antarctic stations are two types of environments where there is an operational requirement for human spaceflight missions. This distinction is important because it involves real-life operational stakes, compared to simulations, which might be in extreme environments, but where participants are investigated for the sake of the investigation. At these facilities, crew members spend days to months in isolation and in adverse weather and environmental conditions, performing a variety of tasks and procedures pertinent to space missions. Analog experiences of this type represent an invaluable source of data acquisition for the psychosocial and cognitive research in extreme conditions.

Space analogs

A space analog (SA) site is a natural location on Earth presenting, to some extent, similarities (e.g., climatological, geological, morphological) with future space mission destinations. An SA facility is an artificial structure or location where conditions representative of certain phases of future space missions can be reproduced and controlled to some extent. A test facility is an artificial structure where environmental parameters are representative of those encountered in certain phases of future space missions, controlled and fully reproducible23. Depending on whether the analog is of the open or closed type (with some extravehicular activity [EVA] possibility or not), and due to the characteristics of the analog design, this is expected to affect performance, psychosocial aspects, etcetera, differently. EVA represents one of the most challenging aspects of space missions and surface exploration; EVA also represents an important part of an astronaut’s work. EVA can be complicated by a number of factors affecting a human, like dynamic weightlessness, working in a spacesuit, difficulties in spatial orientation, etc24. Not every analog habitat in SAs is created with the development of a space habitat prototype in mind. With the term ‘habitat’, we commonly mean the set of physical and chemical factors that characterize the environment in which a species lives. But if we broaden the definition of habitat, we can indicate an environment congenial to human needs and incorporating the social, as well as physical space. Habitats can be considered the result (or the best compromise) of the relationship between human beings and technologies in environments where survival depends on those technologies, hence their integration into the requirement and constraint definitions of the habitat. Simultaneously, these technologies and the correlated subsystems are influenced by extreme environment conditions. Many facilities were established only to simulate or test certain aspects of crewed space missions. Cohen proposed a six-level technology readiness level (TRL) scale for simulators that focuses directly on models designed for scientific and training purposes25 (Table 1). According to Table 1, the first TRL is reserved for conceptual projects and small-scale models, allowing the determination of basic construction dimensions. The second TRL is reserved for testing conceptual assumptions and architectural experiments. The third level gradually moves into full-scale concept testing and initial integration attempts of the project or its subsystems. This third stage is the earliest for any structure that could count as an analog habitat since it could, in principle, host a certain level of analog test or mission simulation. We provide a table summary of selected analog habitats – Habitation Readiness Level (HRL) and TRL factors – for available SAs and simulators.

The habitable volumes in historical vehicles listed in the Human Integration Design Handbook (NASA/SP-2010-3407/REV1, pp. 669–670) are the logarithms of mission duration according to the formula: habitable volume per crew member = 6.67 * ln (mission duration in days) −7.79. This provides a preliminary value that analog habitats could try to replicate or modify depending on a mission’s simulation nature and requirements. A volume per crew member for missions up to 12 months of approximately 20 m3 could indicate a minimum analog habitat volume for long-term simulations, given that the facility has a compatible infrastructure. The value representing the minimum volume for the crew to efficiently perform their tasks is 10 m3, while the minimum tolerable volume is 5 m3. Note that the upcoming Artemis II mission will provide 2.5 m3 per crew member for a 10-day mission and will potentially update data on performance and tolerable limits in such conditions26.

Connolly et al.27 focused on determining the habitation readiness level (HRL) (Table 2). For the present study, the most important levels seem to be the fourth, fifth, and sixth, focusing on tests of full-scale projects with varying degrees of integration and material selection. Analog habitats will fall within this range, but not all of them. Not every analog habitat was created with the development of a space habitat prototype in mind. Many facilities were established only to simulate or test certain aspects of crewed space missions. Following this line of thought, certain characteristics of analog habitats’ facility design and location could be derived to compare a research potential for future investigations. Analog facilities are often created to serve a specific scientific purpose impacting the design, location, and scope of structures.

Table 3 provides an overview of various analog habitats’ habitable area and volume per crew member. Additionally, the table includes estimated TRLs based on the available literature. The HRL was estimated for habitats referred to as habitat prototypes in the literature. The overview of selected analog habitats’ features characteristics such as date of creation, country of origin, and the type of environment represented. The table presents a curated list of habitats with publicly available data, illustrating the diverse range of environmental conditions recreated to facilitate scientific research. Notably, the potential for reproducibility of scientific data is also discussed, which highlights the importance of controlling conditions in these analog environments.

Simulations

In some cases, SAs are used to simulate complete or partial mission scenarios. A remarkable simulation was Mars 500, which started in June 2010. It simulated a round trip to Mars, with a total duration of 520 days, including 20 min delay in communications with Mission Control. The crew consisted of six men in total from Europe (2), China (1), and Russia (3). The installations were built ad hoc in Moscow with different chambers that simulated the spacecraft used in their trip to Mars, another for the landing module, and one final chamber for a Mars surface EVA simulation.

Research stations

Other locations might provide good conditions to investigate the consequences of spaceflight, and they are right here on Earth, like Antarctica, with submarines, etc. This is especially relevant for isolation, team dynamics, and adaptation to extreme environments. Human research in Antarctica is carried out at various stations. One is the McMurdo Station on Ross Island28. McMurdo was founded in 1955 by the United States Navy 29. Another base in Antarctica used as a spatial analog is Concordia, a permanently crewed French-Italian research station located 1000 km from the Antarctic Ocean coastline. The Concordia base, a major outpost of glaciological and astronomical research, has been used for experiments on the impacts of factors like isolation, confinement, cold, and darkness on brain functions, psychological reactions, and teamwork functions17,30.

Currently, 47 such stations are in the Antarctic and Sub-Antarctic regions, operated by 20 different nations. The populations of these stations vary from 14 to 1100 people during the summer months (October to February), and from 10 to 250 people during the winter (March to September). Depending on location, evacuation from these isolated environments can be difficult, if not impossible during winter. Although the purpose of these stations is not space research per se, many of them are helpful to study space-related aspects, especially behavioral and psychological performance and societal factors due to their physical characteristics and extreme environments, among others. The Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station (FMARS) is one of the two Mars-simulated habitats (or Mars Analog Research Stations) established and maintained by the Mars Society. This Arctic station is located on Devon Island, a Mars analog environment and polar desert, about 165 km (103 miles) northeast of the village of Resolute in Nunavut, Canada.

Expeditions as space analogs and behavioral health and performance research opportunities

Expedition analogs involve groups traversing challenging environments with the aim of accomplishing a specific goal, for example to recreate the experience of early polar explorers, drawing attention to climate change, proving human capacities, or setting new records for speed and distance. Such expeditions may involve polar treks, sailing expeditions, high-altitude mountaineering teams, or teams crossing desert areas (e.g., ref. 31). A similarity across these endeavors is the need to function optimally as a team to reach goals in extreme, shifting, and potentially dangerous environments. Moreover, physical exertion and risk of physical injuries are often present. As analogs to space missions, expeditions may help in understanding how individuals and teams function in environments involving long-term transit, with applications for a journey to Mars and exploration of the Martian surface. Importantly, these settings may also be used to evaluate countermeasures to optimize individual and team well-being and performance. The information from expeditions differs from analog missions where people live and work in the same environments over time, which may be more relevant for human settlements tasked with exploring the surface of Mars32.

Polar expeditions include excursions and sojourns in summer camps or research stations throughout the year. People on such expeditions generally experience psychological changes because of exposure to long periods of isolation and confinement, and extreme physical environments. Symptoms include impaired sleep, impaired cognitive ability, negative affect, and interpersonal tension and conflict33.

Main areas of behavioral health and performance research in space analogs

Changes in psychosocial and behavioral performance are known to occur during human spaceflight missions, and these can be attributed to environmental conditions (e.g., confinement, noise, workload, social situation, provision of nutrition). Physiologically, changes are reflected and measured by changes in the neurotransmitter system, structural changes in the brain34,35,36, cardiovascular and immune function changes, and others37,38,39.

Cognitive aspects

Analog environments share yet another feature with spaceflight: the scarcity of research on cognitive performance. This issue is well described in the milestone work of ref. 40 (Casler & Cook, 1999). Surprisingly, more than 2 decades after publication, their analysis remains largely unchallenged.

Cognitive skills, like visuospatial orientation and its neural correlates, are also affected by factors such as increased social isolation, confinement, sleep disturbance, and increased stress levels, as they have a direct influence humans’ physiological and psychological well-being41. Poor sleep quality also leads to slower performance and higher error rates when navigating in newly learned environments42, and chronic stress leads to deficits in spatial orientation43,44, probably due to disruptions in neurochemical support networks45,46. Both Antarctic summer and winter crews have shown severe sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances associated with altered vigilance47,48. During Antarctic overwinterings, many Antarctic crew members exhibited a combination of depression, irritability, cognitive decline, sleep disorders, and altered states of consciousness, which were coined “The Big Eye”, or the winter-over syndrome49,50,51.

Neurocognitive changes, fatigue, circadian rhythm disturbances, sleep problems, and changes in stress hormone levels and immune functioning have been observed in situations that mimic some aspects of future human space missions20. For example, during the Mars 500 study, there was a decrease in participants’ perceived physical state, their psychological state, and their motivational state during the period of isolation. In addition, there were specific changes in the cortical activity of their brains, and specifically this activity decreased over time52.

Stahn et al.35 were the first to demonstrate structural brain changes associated with Antarctic overwintering missions. Their eight participants exhibited a reduction of approximately 7% +/− 3% in hippocampal volume of the dentate gyrus after their winter stay. This confirmed the relevance of overwintering as an analog research environment, considering the similarities with the results of Salazar et al.36, who showed structural adaptations between pre- and post-flight measurements of brain connectivity related to spatial working memory.

Psychosocial and emotional aspects

The psychological resilience, performance, and well-being of individual astronauts and the relationships between crew members are vital to the success and safety of space missions53 because, especially in long-term missions, the human psyche is a key factor. Therefore, psychological impacts of extreme situations are of great concern and have become an issue of major importance for the outcome of missions54,55.

Recognized as a key factor, psychological adaptation is considered a dynamic process of adjustment to the changes in physical, social, and psychological demands and constraints of environments (e.g., refs. 56,57,58). During space missions, astronauts are exposed to a number of challenging living and working conditions that can impact their mood, well-being, and team interactions. It is important to distinguish that people working on the International Space Station (ISS) may be exposed to lower levels of psychological stress than teams that target missions farther from Earth, as well as longer mission durations.

On the ISS, astronauts are primarily confronted with effects of weightlessness and physical adaptation processes. In this context, hypogravity has an impact on movement coordination, cognitive performance, and orientation ability59. Similarly, sleep disturbances play a role60. In diary studies, astronauts increasingly name work processes, adaptation processes, and difficulties in external communication as problems61.

Indeed, Earth environments can provide excellent analogs for spaceflight without physically resembling spaceflight, provided many of the stressors exerted on human participants are made parallel62. Different hazards and factors are tested in other analogs, such as fields of gravity, isolation, confinement, space radiation, and sustainability in space63. In this regard, naturalistic environments offer a better opportunity to conduct research that addresses difficulties in long-term missions, in particular64. Compared to missions in low Earth orbit (LEO) or on the ISS, these environments show a higher complexity to evacuate people in emergency situations, which allows a more authentic production of risk experience and resulting action options. People who overwinter, for example, regularly participate in much longer missions compared to ISS astronauts. In addition, there are fewer rotations in the teams, which allows for more long-term observations of team dynamics. Furthermore, teams in the Antarctic or other simulated missions often act more autonomously or simulate time-delayed communication, which also corresponds to a future Mars mission. A recent overview of perceived challenges in analog environments65 identified several key domains regarding challenges, including sensory deprivation, sleep, fatigue, group dynamics, displacement of negative emotions, and gender-issues, along with coping strategies like positivity, salutogenic effects, job dedication, and collectivistic thinking.

Analogs have attempted to reproduce the unusual and constraining living conditions of extreme situations, but also of working in restricted and uncomfortable spaces. They have shown the potential to capture different psychological and emotional aspects associated with space missions. In analogs, constraints and danger are obviously less severe than those in actual environments of spacecraft. However, these analogs allow for the examination of social, emotional, occupational, and physical stress experienced by the participants in specific, unique conditions66.

Especially with respect to planned long-term missions, analogs offer the possibility to recreate extra-planetary situations. They also allow psychological experiences to be induced that are not currently recreated in space (e.g., ISS). These include the ‘earth-out-of-view’ phenomenon, which can be simulated by building a habitat. Analog missions also offer the possibility of specifically simulating relevant aspects, such as time-delayed communication in the case of a Mars mission, and to record their effects on the interaction behavior of humans.

Analog settings may also provide knowledge about psychological and interpersonal reactions likely to occur in different mission scenarios and opportunities to empirically test the efficiency of interventions to manage dysfunctions and support the crew. This has the advantage that focused psychological interventions can be tested and planned. For example, expeditions may give more insight into resilient teamwork in stressful and potentially dangerous contexts. Studies of personnel overwintering at Antarctic stations or crews isolated in confinement chambers can help to understand the impacts of stressors like sensory and social monotony.

Findings showed that extreme situations can induce adverse effects including dysfunctional responses to stress in ground-based studies such as very high-altitude simulations (COMEX Everest in 199767), bed rest68,69,70, and a space simulation in the Arctic71 or Antarctic72. Contrary to these studies’ results, a significant decrease in stress was measured during the ground-based Mars 500 experimentation73. These discrepancies can be explained by the environmental conditions that were different from an actual space mission with possible clean evacuations and no physical dangers. These findings showed that isolated, confined, and extreme environments (ICEs) might not systematically induce stress leading to maladaptation in these specific contexts. Indeed, a certain level of stress is considered necessary for adapting to the demanding situations by mobilizing human resources to help adapt49,70.

During a longer stay in the context of an analog mission or a wintering in Antarctica, participants experience other conditions that can affect them psychologically (e.g., restricted social interactions, separation from family and friends, limited telecommunications and privacy), specific emotional changes, occupational drawbacks (time pressure, limited autonomy, alternative periods of high/low workloads), as well as environmental and physical challenges (e.g., unusual light-dark cycles, variations in weather and atmospheric conditions, low humidity, extreme cold, sudden storms and violent winds, long periods of confinement indoors)33,74,75. Both sensory monotony and social monotony have been considered major emotional stressors76,77. Astronauts often have certain personality traits, like high extraversion and openness to experience, which can be challenged in monotone environments.

Longer missions allow for the analysis of time duration effects and can be used to postulate predictive factors such as the third quarter phenomenon78. The data are inconsistent, but anecdotal evidence has suggested individuals’ higher passivity, a reduced problem-solving ability, and fewer adaptive coping mechanisms used toward the third quarter of a mission30.

In addition to intrapsychic difficulties, interpersonal challenges between participants have been observed. For instance, team cohesion and leadership have appeared crucial in extreme environments55. Research in different extreme situations on team cooperation and leadership has shown that four main objectives are imperative for achieving missions: (1) the setting and clarification of group goals; (2) the improvement of interpersonal relationships; (3) the adequacy of the leader’s behavior; and (4) the clarification of individual roles (i.e., the clarity of the responsibilities linked to the roles but also to their acceptance by the members seemed to be major social variables inherent in the dynamics and cohesion of a team)79.

Future long-duration space missions will include heterogeneous crews, particularly in terms of culture and gender80. The heterogeneity within a crew could generate risks of stress and interpersonal tensions linked to differences in languages and cultures81. In the international polar station Concordia peopled by winterers of various nationalities, social interactions with the same limited number of people over a long period were associated with a decrease in professional performance according to both cultural characteristics and professional status75. However, heterogeneity is not always harmful; it can even become conducive to adaptation when the group manages to establish common values and objectives and to accept these cultural differences with curiosity to better share the extraordinary and unique experiences of a space mission81. Research on gender has even suggested that the presence of gender balance can promote functioning and exchanges within the group71.

This body of research tells us that these factors are not harmful themselves but depend above all on individual and collective representations which can benefit from prior psychological preparation54,73. Indeed, many studies of extreme psychology have focused on the pathogenic effects (e.g., dysfunctional stress, disturbances on health, well-being, and performance) and have largely ignored the salutogenic effects (e.g., personal development, positive experiences, pleasant emotions, constructive relationships) of adaptation to these extreme situations33,82.

Nevertheless, the research on analog missions still has many gaps in psychosocial and emotional areas. Three main steps might be taken as countermeasures: (1) selection and pre-mission training (e.g., stress management, interpersonal training, leadership, coping strategies); (2) monitoring and supporting crews during missions (e.g., telepsychology); and (3) monitoring and supporting crews during the post-mission phase (i.e., rehabilitation, psychological follow-up)72.

First, there is a need for a better focus on selective processes in the context of personality psychology diagnostics. Although analogs are rising in use, selection criteria remain inconsistent. As much as selections presently target individual performance, future selections should also address team compositions and choose participants in relation to potential team functioning. Furthermore, selections should address the needs for long-term missions more than for short-duration stays. This may include a shift in personality choices, as much as a stronger focus on intrapersonal emotion regulation strategies and coping mechanisms, but also selecting for social reciprocity, patience, and low neuroticism. Research should address and test selection criteria and evaluate them post-mission.

Future long-term missions will not allow the possibility for ongoing crew support and will require high levels of autonomy, also regarding psychological well-being. Therefore, crews must be trained prior to their missions to cope with conflicts, mood-shifts, and minor clinical symptoms by themselves, fostering the need for evaluating training methods for individuals and teams in ICEs. Teams should be taught to recognize and address psychological questions with specific debriefing and coping techniques. The functionality of these should be evaluated post-mission. Analog missions offer the potential to test targeted interventions to build and stabilize individuals’ psyches. However, interventions are most often tested only in simulations, so the reliability of many interventions is severely limited. Therefore, interventions that work should be operationalized and replicated. Salutogenic concepts can play a role in this process. Further improvements in the development and validation of preventive countermeasures would minimize dysfunctional psychological outcomes to promote salutogenic or psychological growth effects64,83 and human adaptation to such environments over a long period.

Much of the world’s psychological research has used parameters like cognitive performance, stress, or subjective well-being as outcome variables for psychological well-being. To broaden the research, more precise variables, including emotion regulation strategies, conflict resolution approaches, and team interactions, should be explored in more detail to help paint a holistic picture.

As a longer mission duration increases the potential of psychological challenges, longer missions (i.e., IBMP Mars 500, NASA CHAPEA) should be conducted. Much psychological research covers missions of a shorter duration (e.g., a few months), showing that the psychological challenge can grow with the length of a mission. Therefore, there is a need for more detailed studies on long-term psychological effects and intervening resource management, perhaps turning to tele-physiological intervention options.

The link between supporting astronaut teams in terrestrial and spatial environments and using artificial intelligent support systems will increase. Future research should question the potential of chat-based models with monitoring and therapy for teams not able to reconnect to Earth. A better understanding of psychological processes assessed in analogs might have practical implications for psychological countermeasures to deal with human factors in extreme situations.

Physical activity/exercise

Physical activity is important for the mental well-being and physical health of astronauts during space missions84,85,86. During missions, physical activity is reduced due to multiple factors, like partial gravity or weightlessness. Fluids in weightlessness disperse differently, with a tendency towards the head when gravity is reduced or missing87. Muscles within the body, including the heart, need to work less because they do not have to counter gravity. Consequently, muscular-skeletal and cardio-vascular deconditioning takes place88. Yet gravity is not the only factor that contributes to reductions of physical activity during spaceflights. The limited space available for daily, working, leisure, or exercise activities is the second factor that determines being more or less physically active89. Space shuttles and stations are very limited in space. The ISS, for example, expands to 932 m3, and many modules must be used in a multi-functional way. Gym equipment needs to be of limited weight, size, storable, and/or multifunctional. Applicable physical activity-related countermeasures must consider these limitations. Another issue is the time needed to integrate sport into the daily mission routine. Space missions are often subject to pressures to operate economically and effectively. Thus, physical activity should also be effective and ideally short, while at the same time exercises to maintain the musculoskeletal system require a certain amount of time.

SAs (e.g., Antarctic Research Stations [McMurdo, Concordia] or high-sea stations [NEEMO] and SA habitats [OeWF, HI-SEAS]) allow physical protocols to be evaluated. These SAs differ in their space volume and capabilities for physical activity to a great extent. Some analogs are closed and contain, more or less, volume/space inside the habitat or even several modules, while others allow or include outside (extravehicular) activities (e.g., Concordia Station). Some have extensive gym facilities, while others host limited exercise equipment (e.g., Human Exploration Research Analog [HERA] habitat). The Concordia Station in Antarctica, for example, covers 1500 m2, hosts a well-equipped gym, and allows outdoor activities, albeit limited due to extreme temperature and hypoxic conditions. The size of the Nezemnyy Eksperimental’nyy Kompleks (NEK) in Moscow, in contrast, is about 550 m3 and contains a small gym; however, it does not provide opportunities to exit the chamber, with an additional planetary surface simulator of 1200 m3. The HERA habitat is also a closed 194 m2-sized module that only provides a very small space for a bicycle ergometer, a mat, and some weights. Austrian Forum missions have a large habitat, but usually do not have any exercise equipment. Thus, team members can only exercise or do yoga with their own weight.

In addition, the freedom or degree of regulation and physical activity prescriptions from Mission Control or SA providers highly varies between SA. Each comes with unique circumstances in terms of schedules or work for the crew members. Some analogs are restrictive regarding the exercise protocol or fully prescribe exercise, while others at least allow crew members to be relatively active during leisure times. While SA isolation missions intend to mimic real spaceflight scenarios, isolation missions at, for example, Concordia Station in Antarctica are performed mainly by professional personnel to run the station, to overwinter at this station, and to conduct research. In some missions, there is a large physical component in the performance of EVAs, as in missions of the Austrian Space Forum, in which the spacesuits already weigh up to 50 kg. Mass and the execution in warm or cold desert regions put astronauts under regular physical stress, which should be accounted for in possible analyses.

Overall, reduced physical activity (for whatever reason) is known to cause multiple physiological changes that affect hormone regulation, immune system functioning, and metabolic processes, amongst others, which directly or indirectly affect individuals’ psychological state, cognitive performance, and mental health. Physical activity is therefore important not only for physical health, but also for cognitive performance and psychosocial aspects (see sections Cognitive Aspects and Psychosocial and Emotional Aspects). Increased physical activity, in turn, has been shown to positively impact individual psychological aspects, such as well-being and cognition90,91. Other collective psychological aspects, like team cohesion, can be improved92,93. Because of this complex interaction, both physical and psychological health should be considered together for ongoing and extended future space missions. Scientific evidence is required to both compare and confirm efficient exercise countermeasures and prepare future missions to Mars or beyond. However, data about the effects of physical activity/exercise from astronauts in space are scarce due to the small number of spaceflights and crew members onboard. In addition, biological sex has not been equally considered in previous studies, which have questioned whether findings generalize to female astronauts.

Moreover, effects of physical activity are difficult to disentangle from other physical and psychosocial stressors, as most studies have lacked a systematic approach, which can only be achieved if research opportunities are restricted per the integration of interacting factors or exclusively designed for exercise interventions. In either case, investigators need to carefully choose and control for the influence of physical activity and concurrently consider present circumstances.

Control groups for exercise interventions have been largely missing because the benefits of regular physical activity are indisputable, and it is an ethical, health, as well as a mission success issue at the end, if physical activity is severely restricted or even forbidden. In some cases, it has been possible to compare more with less physically active crew members retrospectively94,95. These studies indicate that the more active people showed a steadier mood compared to the less active people, who showed a deterioration of mood. A study including a non-isolated control group might highlight the short-term and severe consequences of exercise abstinence96. In general, studies are required in which crew members maintain a regular profile of exercise behavior in order to be meaningful, which leads to the corresponding problem of exercise adherence or motivation. Consequently, the existing literature on the effects of physical activity or exercise training for physical and mental health outcomes in SA environments is heterogeneous and should be reviewed with caution.

During SA missions, in fact, most of the existing studies found no severe psycho-physiological impairments when the exercise was performed on a regular basis89,94,96,97. Schneider et al.52 focused on the ability of exercise to counteract psychophysiological functioning. Over a 105-day isolation period, the authors evaluated the acute effect of an incremental bike test on mood and brain activity, and they demonstrated that exercise is a suitable method to counteract psycho-physiological deconditioning during confinement52. A rare example that compared different exercise protocols was provided by Fomina and Uskov98. They assessed the efficacy of two physical activity interventions (i.e., interval running training in the aerobic-anaerobic power zone vs. continuous low-intensity running training in the aerobic power zone) to prevent disturbances in the motor system that accompany long human stays in weightlessness. The authors reported that the low-intensity training group experienced a greater level of reduction in physical fitness than the interval group after completing the spaceflight98. However, between the participants of both groups who were able to perform the post-landing incremental running test (three out of eight from the low-intensity group vs. all the interval training group), no significant differences between groups were found in terms of maximum running speed, maximal lactate level, or changes in heart rate. For cognitive functioning, neuro-psychological findings by Schneider et al.89 indicate that running is more beneficial than bicycling or resistive, expander, or vibration platform exercise89. Others suggest for psycho-physiological health that it might be possible to refrain from daily exercise regimes96, at least for month-long missions.

To date, the best option to mimic microgravity on Earth, also for long-term investigations, is head-down, tilted bed rest87. Bed rest allows for the mimicking of physical unloading and headward fluid-shifts that occur in weightlessness, which is why investigations of head-down bed rest are irreplaceable in SAs, and they have been extensively reviewed, also in regard to physical activity/exercise (e.g., refs. 99,100).

Besides these SA studies, many other physical activity interventions have been evaluated on the ISS; an overview of this research is provided by Loehr et al.85. In their publication, physical activity interventions to counteract and minimize any mission impacts were subdivided into three distinct phases (i.e., pre-flight, in-flight, and post-flight). This distinction was important and will be crucial for future investigations to account for when designing physical activity interventions and holistically evaluating the effectiveness of physical interventions for in-flight and post-flight human physical performance. Furthermore, Loehr et al.85 specifically emphasized the difficulty of predicting appropriate exercise loads for use in microgravity and indicated that future research should attempt to increase the understanding between heart rate, treadmill belt speed, and subject loading. Besides this first review of physical exercise interventions in space by Loehr et al.85, two other reviews on this topic were recently published101,102. Jones et al.101 focused on the application of concurrent training in space and formulated several guidelines. For example, if strength and aerobic exercise are performed in close proximity, strength should precede aerobic exercise101. Moreover, concerning strength exercise, eccentric strength training is recommended. In terms of aerobic capacity, cycling- and/or rowing-based high-intensity intermittent training should be the preferred training method101. Moosavi et al.102 systematically reviewed the efficacy and limitations of exercise countermeasures on the musculoskeletal system under microgravity in humans and concluded that the heterogeneity of study designs, methodologies, and outcomes deemed their review unsuitable for meta-analysis. Their main message was that the most effective exercise countermeasure was likely to be robust, individualized, involving resistive exercise, and primarily targeting muscle mass and strength102.

Even though these exercise protocols were found to positively counteract some of the spaceflight-associated negative effects on human functioning103, it is important to continue assessing and revising the efficacy of other physical activity interventions. They should not be neglected; despite the benefits of physical activity, exercise protocols might also lead to an increased stress experience. This might be reflected in saliva cortisol levels from a comparison of crew members of two isolation missions involving different exercise training volumes96. Exercise also leads to a strain on the immune system104. Likewise, studies have shown that high physical stress can have a negative impact on sleep95 and psychosocial and emotional aspects (see section Psychosocial and Emotional Aspects). Additionally, sport increases the risk of injury and draws on physical resources. These aspects demonstrate that it is important to derive a precise definition of the exercise intervention target with a holistic perspective and to adapt protocols accordingly (mental health, physical well-being, leisure time) to avoid unintended countereffects. The evaluation of multiple outcome measures (e.g., mental health, physical fitness) will be highly valuable for providing insights into the question of the most optimal physical activity protocol for applications in space. Moreover, the development of an effective method (e.g., questionnaires, wearable movement trackers, and/or physiological outcomes) to validly estimate the absolute physical activity level during long-term missions will also be crucial.

Also notable is the importance of physical activity in human spaceflight and SA missions. After all, physical activity/exercise has a positive interacting effect on astronauts’ health, well-being, physical fitness, immune system105, and psychological well-being and mental health106. But before the research on physical activity and exercise regarding human spaceflight is continued, the following shortcomings, remarks, and recommendations should be understood. First, when planning a future analog mission, physical activity should be consciously incorporated into the design and architecture of the habitat, as well as the planning of daily activities. Protocols should be oriented to given workloads and daytime and sleep schedules, but also involve alternating physical activity in the form of physical experiments or EVAs. Physical activity should be incorporated in a balancing, but not overstraining, way. Crews should be given opportunities for exercise that are easy, practical, and attractive to implement in their particular contexts. Less strict exercise protocols can feel more relieving than rigid physical activity protocols. These, together with permitting a higher degree of self-determination and individual preferences when designing exercise interventions, would help support individuals’ adherence to exercise prescriptions107,108 and augment mental benefits109,110,111. Finally, new possibilities for physical training should be taken into account that propose, for example, the use of virtual technologies to exercise. Physical training in virtual reality (VR) can positively impact physical fitness, mental well-being, and possibly induce rehabilitative effects112. Modern fitness trackers and wearables, including individual exercise diaries and motivational features, might help to document, examine, and reach individual exercise protocol targets.

Ground-based models for weightlessness as space analogs

The evident constraints of using the space environment to study space-related physiological adaptations have led science teams to focus portions of their research on ground-based analog models that mimic some of the effects of weightlessness. Different models can be used on Earth to simulate microgravity, for instance. The microgravity analogs discussed in this paper include the head-down bed rest, the supine bed rest, and the dry immersion models. They have their own advantages and disadvantages regarding their effects on the different physiological systems113, and they can be seen as complementary to the exercise/physical activity study domain.

Bed rest model

The model most often used in humans is the −6° head-down bed rest (HDBR) model. This model, used since the 1970s, reproduces different aspects of spaceflight, such as microgravity, physical inactivity, and confinement. Changes induced by HDBR include the upward shift of body fluids, the absence of changes in posture, unloading of the body’s upright weight, reduced energy requirements, reduced proprioceptive stimulation, altered social interactive and work/rest cues, and a reduction in overall sensory stimulation87,114. However, in all bed rest models (supine or head-down tilt [HDT]), the gravity force vector remains present but transferred from the head to the feet, to the chest, and back direction. All factors, including physical activity, nutrition, sleep/wake cycles, and social activities, were well controlled for and standardized across the studies. The selection of volunteers included measurements of physiological parameters, blood tests, and a psychological selection by experts in this area. A core set of standardized physiological measurements was also defined in order to compare the data of different studies115. Standard measurements have also included a set of psychological assessments and questionnaires.

The duration of bed rest depends on the objectives of the experiment. Five days of HDBR are sufficient to induce a cardiovascular deconditioning, but long duration bed rests are needed to assess the effects on human bone. Supine bed rest is also a model of inactivity leading to cardiovascular deconditioning and musculoskeletal changes. This model induces a homogeneous fluid distribution in the body, but the fluid shift is less marked than in HDBR. Therefore, this model is not currently used as a ground-based reference model for spaceflights. Long-duration bed rest is widely employed, however, to simulate the effects of microgravity and test the effects of countermeasures especially on the musculoskeletal and cardiovascular systems. This model also provides unique opportunities to assess interactions between the different physiological systems87. These types of experiments represent a well-accepted method to simulate an acute stage of human adaptation to microgravity in spaceflight116. People undergoing bed rest can experience high anxiety and psychological stress117, as well as headache, sleep disturbances, and other types of discomfort due to cardiovascular changes caused by the head-down position117. It is evident that these factors can cause a deterioration in a human’s psychological condition and lead to performance decrements.

Different types of countermeasures have been tested in HDBR, including physical measures, such as different muscular training (aerobic or resistive), vibrations (to prevent bone changes), lower body negative pressure (LBNP) sessions, pharmacological, and nutritional countermeasures. Artificial gravity could represent a global countermeasure to act on different physiological systems. However, many questions remain to be answered if it is to be implemented on future spaceflights per its amount, association with exercise, and the inter-individual responses to hyper-gravity. Finally, a ground-based ongoing simulation program was defined by the ESA to assess the effects of centrifugation in association with exercise.

Dry immersion model

Complementary to HDBR, a Russian-developed model has been recently implemented, called dry immersion (DI). It consists of immersing a subject in thermoneutral water who is covered by a fabric that prevents their skin from contact with the water. Specific support unloading, profound mechanical and axial gravitational unloading, enhanced muscular inactivity, acute fluid shifts, and fluid transfers inherent to DI make this tool particularly relevant for studying physiological responses and deconditioning to gravity118. It is a good model to study neuro-motor and postural disorders related to microgravity. DI induces a prompt orthostatic intolerance, rapid metabolic impairment, and even impacts the early biomarkers of bone remodeling119. The HDBR and DI models provide new insights for evaluating the effects of physical inactivity and countermeasures on mental health and psychomotor performance.

Virtual reality/augmented reality-based research in ICE conditions and space analogs

The use of virtual environments to treat physical ailments like pain (e.g., in the context of pain management therapy with burn victims and cancer patients) or psychological disorders, such as PTSD and phobias (in the context of CBT and exposure therapy), has been tested in various studies and shows promising results120,121,122. Also, the area of providing VR/extended reality (XR)-mediated positive psychological interventions holds much promise. Immersive virtual reality (IVR) environments may become vessels for psychological interventions that help maintain good mental health and well-being, and that support cognitive functions. Hence, they may help mitigate negative effects of ICE conditions. IVR tools used with real-time monitoring and analytics, including psychophysiology, could constitute responsive systems that adapt to the responses and needs of individuals. This is an active area of current VR-based research.

Ground-based facilities designed for analog studies have differed vastly. Diverse factors and types of stressors have been introduced to these environments, and they provided varying degrees and kinds of challenges to participants. Due to this large variability among experimental conditions, protocols, and measurement methods, there are a lot of difficulties in comparing results obtained in different studies and settings123. Still, comparisons are necessary because a single analog mission provides a small sample size and, therefore, small effect size. Therefore, a key strength of using VR or XR environments in this context lies in the replicability of the studies done solely in VR124. VR studies, when conducted correctly125, have the potential to mitigate many risks associated with data not being comparable across different research venues126. Immersive virtual environments can combine free exploration with a high level of experimental control, both in terms of physiological and behavioral measures127. In VR studies, one can collect synchronized psychophysiological data, like data on body and eye movement and changes in cardiac function and skin conductivity, often in easily replicable conditions. For example, eye movements can be monitored by an eye-tracking system built into a headset, while motion capture data can be obtained by trackers. Moreover, it is possible to employ sensor networks for EEG/PPG, GSR/EDA, EOG, EMG, and other parameters. Virtual environments may also include self-report measures embedded in VR128. The equipment and software required to conduct such studies are becoming increasingly available, portable, and easy to use. Thus, such studies may be successfully conducted by the users themselves in various locations outside of research laboratories, including analog habitats and further-out space research facilities like the ISS, and in the future, Gateway. Accurate IVR tools may closely mimic environments, potentially down to the whole study experience, and bridge the gap between different habitats, helping researchers conduct larger collaborative studies across diverse crews and at different sites.

IVR can also simulate environments beyond ICE conditions, typically associated with daily terrestrial life. IVR representing nature has been used to reduce stress levels and improve mood. This positive change was observed both with subjective and objective measures of stress and relaxation. Still, individual preferences for the characteristics of the scenes presented and their dynamics may affect the subjective evaluations of experiences. Personal preferences and subjective impressions have made no difference on objective physiological measures of stress reduction (in HRV and EDA) but have captured the difference between positive relaxation versus boredom129,130. IVR can also be used to combat negative effects of monotony and lack of sensory stimulation in ICE environments, which may result in a lack of motivation and decrements in cognitive performance129,130. Also in this context, the effects of exposure to artistic IVRs were recently studied during an exploratory ALPHA-XR mission in an analog habitat131. The results of this pilot case study suggest that interactive artistic virtual environments are a promising alternative to real environments, enabling the exploration of nature, and they might be equally effective in mitigating some of the negative psychological effects of ICE conditions on crews.

Several complex solutions such as the EARTH of Well-Being system or ANSIBLE were tested during long-term Martian simulations. The EARTH (i.e., Emotional Activities Related to Health) of Well-Being system was based on a positive psychology intervention. The system helps induce two positive emotions (relaxation or joy), teaches several techniques of emotion regulation, and helps users practice positive reminiscence and future planning132. ANSIBLE (i.e., A Network of Social Interactions for Bilateral Life Enhancement) was designed as a communication support toolset for human-human and human-virtual agent interactions. The toolset helps combat sensory and social monotony and gives opportunities to recall positive memories, participate in cultural and familial rituals, and create shared experiences60. The research pointed to significant differences in the use of the systems and their various modules by diverse users, leading to the conclusion that such systems should offer advanced personalization and customization capabilities. Both studies were conducted several years ago using personal computer VR environments and would be worth repeating with IVR and VR headsets.

While the subject of training in VR environments has been previously explored in the context of space133,134,135, there is room for further studies, especially in terms of providing just-in-time training, since crews are often expected to retain a large amount of information136,137. For this reason, XR-based support mechanisms, reminding crews about protocols in a hands-free way when they are needed, may lessen the load on crews to recall all the details of instructions. These mechanisms may also benefit from the real-time support of Mission Control staff who could present real-time instructions on-screen28,135,138.

Collaboration and communication in ICE conditions can also be challenging, as people exposed to them may experience anxiety, anger, or fatigue. Moreover, conflicts that develop in such conditions among crew may be transferred to the Mission Control staff, and communication quality may suffer. An exploratory ALPHA-XR mission attempted to evaluate this aspect of missions in a pilot study related to the quality of communication in analog Mission Control briefings. The study hinted at VR improving communication when compared to voice-only briefings, potentially due to participants’ abilities to better interpret gestures and express and receive attention.

VR environments in analog habitats may also replicate diverse planetary terrains139. Mars’ surface can be accurately mapped for rover driving simulations140, but also for pre-EVAs and mission training133,141 and, in analog habitats, EVA missions themselves. Moreover, such IVR environments for use in analog habitats, also replicating potential EVAs, may be co-designed with astronauts to contribute to a realistic ICE experience and to provide testing grounds for the practical training of complex skills.

The need to use VR in training with complex hardware has emerged in areas where the machines to be operated are expensive, and there is a high risk of damage in the preliminary stages of training. German space agency DLR initiated multi-user access to their virtual lab for the COLUMBUS module project. More advanced scenarios, involving operations of the remote robotic manipulator system, also referred to as the Canadarm, have taken place in NASA’s Johnson Space Center Virtual Reality Lab. Station arm operators were able to train in an immersive environment with virtual spacewalkers mounting the end of the arm. In summary, XR (VR/augmented reality [AR]) technology has many potential benefits for this field, from training, to psychological well-being, exercise, and technical task benefits.

Operational aspects/planning of maintenance of space analogs and extra vehicular activity

SA missions should ideally include several experienced teams who manage the facility, analog astronaut selection, pre-mission, mission, and post-mission operations, and research projects and Mission Control teams (including the mission support members). It is crucial that these teams work well together and share information in a structured and documented manner. Proper science data archiving is also necessary for successful mission operations and research data storage. An example of a well-functioning science data archive is the Multi Mission Science Data Archive of the Austrian Space Forum.

Analog missions may include communication latencies that mimic the signal travel-time between Earth and Mars, as well as complex mission architectures that may include multiple EVA teams, robotic assets, etc. The coordination effort to optimize asset deployment grows exponentially with the number of teams and operational assets, leading to situations where the traditional Mission Control architecture (a.k.a., concept of operations [ConOps]), like that applied during ISS operations, might not apply. Thus, crew members’ decision-making may shift towards being more autonomous from Mission Control, especially in the field. While some functions may be automated (e.g., the monitoring of consumables), the crew will still be tasked with decisions that must be made in the field and at times without inputs from Mission Control over extended periods (e.g., due to a loss-of-signal from planetary constellations). More decision-making autonomy in increasingly complex environments will likely increase stress load. For instance, in less complex mission architectures, such as at MDRS, the stress load may not have a significant short-term impact on the crew. Conversely, more complex mission architectures, for example during AMADEE missions and at HI-SEAS, the missions can be significantly more challenging and thus stressful for the crews.

Performing EVAs today requires extensive training, preparation, and ground support and are – compared to other daily ISS activities – a rare event during orbital missions. However, projected EVA frequencies may rise to as high as several sorties per week for each Mars mission crew member, rendering it a routine task within weeks. Also, the amount of self-reliance regarding spacesuit maintenance, repair workflows, and system checkouts will generally field-forward many tasks that are nowadays ground-based or ground-supported. It is a general observation that complex EVA protocols that require human attention may deteriorate under the scrutiny of how crew members observe the protocols, potentially leading to additional risks. EVA-related protocols can be burdensome (e.g., waiting for airlock decompression time), but they are necessary for the success of mission simulations. If the analog protocols leave too much room for individual crew decisions, this can cause the fidelity of the simulation to decrease to the detriment of the mission and the analogs’ fidelity. Thorough and well-applied EVA protocols focused on crew-centered ConOps may not only lead to a more efficient and safer analog mission, but also to a more scientifically useful mission dataset.

In addition, crew recruitment seems to be a performance indicator of the professionality of an analog mission (e.g., random crew compilation vs. careful selection process). There is a wide range of selection processes both for crews and support personnel. The appropriate selection is a generally recognized predictor for in-sim social and technical challenges; for instance, the Austrian Space Forum analog astronaut recruitment process proceeds over a period of 5 months, evaluating 637 individual parameters ranging from anthropometric measurements, health parameters, psychological assessments, technical competence tests, and others.

Maintenance

Habitats need proper maintenance between missions, distributed amongst crew members as housekeeping, regular maintenance in and on the habitat, during and at the end of each mission. This not only helps to maintain the facility in a normal working condition, but it adds to the fidelity of maintenance being an important part of an actual space mission. Habitat maintenance generally needs to be scheduled as part of the mission planning and crew training on habitat management and operations. Depending on the analog facility, such training and maintenance work can take between several hours to several weeks. Studying the crew’s ability to learn and implement the maintenance could lead to valuable data on the crew members’ abilities to perform such tasks and operational work, as well as their abilities to learn these new tasks during the training they are provided with.

Safety & management

Safety aspects are vital for the success of analog missions to standardize operations and satisfy legal and regulatory border conditions and scientific mission performance. Also, many analog missions are performed in isolated and/or extreme environments, increasing, for instance, the risk of traumatic injuries by a factor of 4 compared to control groups based at the Mission Support Center142. Unfortunately, various analog habitat operators undervalue planning for operational safety and have limited or lack protocols in place for the risks that may be pertinent to analog missions. Accidents reported range from minor trauma to electrocution with associated heart arrhythmias, gas and fluid poisoning, hypo- and hyperthermia, and exceeding permissible occupational standards (e.g., CO2 inhalation in poorly ventilated spacesuit simulators). There have been life-threatening events both because of poor safety measures and little to no protocols in place for, for instance, evacuating an injured crew member. Oftentimes crew and Mission Control members do not know where the nearest level-1 trauma center is located and how to organize medical evacuation. For these reasons, crew members should get both facility-related safety training and outdoor emergency medicine training for analog sites in remote and/or extreme environments, and these are oftentimes more appropriate types of training programs than spaceflight-compatible protocols offer.

Safety measures also need to be in place within the analog station itself and be subject to rigorous monitoring and – preferably external – assessments. For instance, there are some analog stations where CO2 levels and carbon monoxide levels are not monitored, which can lead to medical issues for crew members. Physiological workload projections before an EVA are also highly recommended, though they are not frequently performed at analog facilities. This is another factor that can increase the risk of injury for crew members and premature mission termination.

Furthermore, simulation quality is connected to the level of isolation, minimizing the intrusion of non-crew individuals. Some analog stations have effective regulations in place to minimize the risk of bystanders who enter test sites but may “over-interfere” with crew operations via management, visits with minimum or no prior notice from site operators, or patronizing behavior detrimental to the crew’s ability to mentally enter a simulation setting.

Finally, only a few analog site operators will have a clear vision of how the research program shall evolve over time, and they often do not have a proper ConOps document (thus, increasing mission risk) or science data archive in place to avoid redundant experiments, and in general, crew members lack a predefined list of success criteria, as customary for space missions. One way to mitigate these deficiencies may be to define ‘analog mission performance criteria’, which allow habitat operators to compare missions, assess their scientific and engineering soundness, evaluate simulation fidelity and complexity, and validate administrative concepts in comparison to other habitats. An example of such an analog mission performance (AMP) quantification is the AMP benchmarking tool provided by the Austrian Space Forum143, which measures the complexity and fidelity of analog missions.

Indeed, design characteristics of planetary habitats are very important not only for survival but also because of physical and social aspects for future astronaut explorers. Space habitats are designed for extreme environments. Astronauts on Mars but also on the Moon will have to work and live inside these habitats while exploring and working outside, during EVAs. Designing a habitat for an SA mission requires intertwining these two main groups of activities (living and working) with the rest of the environment: This leads to both human-machine and human-human interactions, which have been defined in ergonomic terms in the SHELL-model (software, hardware, environment, liveware)144. Recent studies have shown the potential benefit of space biology (plants) for psychological support of the crew145. If we consider a habitat not as a union of different engineering-driven subsystems but as the result of requirements coming from human needs and their interaction with the environment, we must change the predominant habitat design approach and involve not only engineers but also space science, architecture, industrial design, ergonomics, medicine, and psychology disciplines, to name a few.

Overall, all these parameters should be integrated into a cohesive SA mission definition. Yet, “too often, programs consider the human element in a human-machine system after making other key decisions, only to raise mission or design problems they otherwise might have avoided”146.

Discussion and recommendations

Beyond the technological aspects, the human factor is now recognized as essential to promote humans’ adaptation to such environments, which might otherwise exacerbate and threaten adaptation processes over a long period of time. Humans in space must not only adapt to unusual and constraining living conditions, but also live and work in restricted and uncomfortable spaces.

The research of analogs is rich in lessons and can help forge necessary models for studying adaptation processes in all their cognitive, affective, occupational, social, and physical dimensions55,147. These studies report that such challenges are not harmful in themselves but depend primarily on individual and collective representations that can benefit from prior psychological preparation54,73.

Psychologists should be involved in the development and validation of interventions to promote adaptation with psychological countermeasures to stimulate adaptation processes and consequently, participants’ well-being and performance148. These interventions are best oriented, for example, towards effective coping strategies for stress and emotion regulation, leadership and team building, a sense of control, and “meaning” in one’s activities49,149. Because there is no substitute for actual experience, these interventions should be conducted with regular exercises and especially practiced during simulated missions in analog situations.

As the recent efforts of space agencies gain momentum towards going back to the Moon with human spaceflight missions, and the human exploration of Mars seems more real than ever, there is an increasing need to research the long-term consequences of long-duration human spaceflight missions. Many SAs are appearing with different degrees of fidelity to scientific methods and goals, with a very diverse panoply of characteristics from environmental, crew composition, habitat design, and duration of missions, to mention a few.

The present study integrated space research experts’ points of view, and more specifically, leading ideas and research from the space behavioral health and performance scientific community. Also, we formulated a set of recommendations and guidelines to assure that the flourishing SA activity serves beneficial and clear scientific objectives in SA research. The main objective of behavioral health and performance and SA research should be to promote the rigorous scientific research of the aspects covered in this review, and in accordance with ESA priorities in this field. Finally, to help facilitate quality assessment of the behavioral health and performance research and SA development activity, we developed a checklist tool and recommendations (Table 4).

Responses