Space exploration and risk of Parkinson’s disease: a perspective review

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the most common neurodegenerative movement disorder. It is caused by atrophy of the mid brain Nigro-striatal projections, resulting in symptoms of resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia and postural instability1. Genetic factors account for <10% of the disease burden with significant environmental contribution2. However, it is not known how the exposome (lifestyle, diet, exterior environment etc.) influences PD pathogenesis3.

Spaceflight (SF)-induced systemic changes are similar to PD. This parallel may be due to the exposome of SF including ionizing radiation (from galactic cosmic rays and solar particle events), microgravity, hypoxia, hypothermia, hypercapnia, confinement and associated physiological/psychological responses.

Review of relevant literature

Anatomical similarities between SF and PD

In the early stages of PD, perivascular spaces (PVS), a commonly observed anatomical structure around the basal ganglia and midbrain4, are affected and enlarged, presenting PVS burden, in patients4. These same regions are thought to be most sensitive to SF5,6, and are associated with PVS burden post long-duration (but not short-duration) SF, among astronauts6. SF induced changes in brain structures and circuitry linked to PD have been reported even after 7 months post-flight7,8. These changes in brain architecture include a sustained grey matter increase in the Basal Ganglia (BG)6,8, which is also seen in PD cases9. Structural changes in other brain regions such as the cortex are reportedly reversed 6-7 months post SF10,11.

Change in gait and postural instability post SF

Gait characteristics can serve as indicators of vestibular, sensory and neuromotor dysfunction, as well as musculoskeletal atrophy resulting from diverse causes (including PD). Post-flight changes in astronaut gait have been extensively documented12 and reflect deficits across multiple systems, although in humans’ symptoms abate after re-adaptation post-flight. The Rodent Research-9 (RR-9) mission, conducted aboard the International Space Station (ISS), includes the only study to date designed to investigate the impact of long-term SF (35 days in space) on motor coordination and gait. The gait pattern analysis in mice before and after returning from the ISS revealed significant alterations in gait resembling the axonal degeneration that occurs during early stage neurodegenerative movement disorders such as PD and Huntington’s disease (HD)12,13,14. However, there was no follow up post-flight study for these animals as they were sacrificed within a day of return.

Radiation exposure and PD

Radiation exposure has been linked to PD15,16. A meta-analysis was conducted from six cohorts in the Million Person Study (MPS) consisting of 517,608 American workers exposed to low-dose radiation, with maximum mean dose to the brain ranging from 0.76 to 2.7 Gy over a lifetime16. Five of the six cohorts had statistically significant positive associations with PD, based on 1573 deaths due to the disease16. This study indicates to us the need to assess the neurological implications of prolonged space travel and the benefits of specific radiation-protection measures. It should be noted that so far, the median time spent in space within Low Earth orbit (LEO) by an astronaut is about a month, which leads to an accumulated radiation dosage of 7.52 mGy. NASA has set the radiation limit for astronauts on deep space missions (such as to the moon and Mars) at 1.5 mGy/day17. For the projected 900-day mission to Mars, the maximum dosage would be about 1 Gy, which is within the range of the MPS study that showed an increased risk of PD.

Changes in metabolites

Homocysteine

Recent findings indicate that SF and PD also share visual symptoms, specifically ‘SF Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome’ (SANS), which is akin to the visual motion hypersensitivity (VMH) reported by some PD patients18. The underlying mechanism for VMH and SANS is linked to mitochondrial dysfunction (MD) and dopamine (DA) depletion18,19. Zwart et al. showed that astronauts affected with SANS had higher plasma homocysteine and iron levels post SF20. Similarly, plasma homocysteine in PD patients is elevated compared to that of healthy individuals, and this high homocysteine level is involved in MD, neuronal apoptosis, oxidative stress, and DNA damage21. Additionally, elevated integrated stress response signaling is observed in the brains of patients and animal models of PD22 as well as post-SF23.

Dopamine

PD is characterized by a loss of dopaminergic neurons in the Substantia Nigra pars compacta (SNpc) region, which results in a decrease in striatal DA. Data from post-flight astronauts suggest decreased levels of DA metabolites, homovanillic acid (HVA) and 3-Methoxytyramine (3-MT), in urine and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), indicating lower DA levels. Simulated microgravity experiments using C. elegans proved that the loss of mechanical contact stimuli in microgravity elicits decreased DA and comt-4 (catechol-O-methyl transferase) expression; and the animals displayed reduced movement24. These results corroborate findings by Popova et al., who showed that space-flown mice had significantly decreased expression of a key DA biosynthesis gene (TH), and genes involved in DA metabolism (MAOA) and O-methylation (COMT), in the SNpc region of the brain5,25, adding to the list of Parkinsonism features in animal models post-SF.

Vitamin D

Deficiency in serum vitamin D (25(OH)-D) is prevalent among PD patients, with levels corresponding to the risk of falls and non-motor symptoms26. Astronauts, too, experience significant decreases in both 25(OH)-D and 1,25(OH)2-D forms of vitamin D, for which they take vitamin D3 supplements during missions23. It is important to note that Vitamin D3 is modified by liver mitochondria into its active form, 1,25 vitamin D, and systemic MD may contribute to the reduced levels23.

Physiological parallels

Both PD patients and astronauts (in-flight and post-flight) complain of olfactory dysfunction (OD) and sleep disturbances. In PD, OD serves as a hallmark for early-stage diagnosis27, while astronauts experience altered senses of taste and smell during (and post) SF23. PD patients present symptoms of REM sleep disorder26,27, and astronauts report space-insomnia including shortened sleep duration, reduced sleep quality, and an increased difficulty in falling or staying asleep23. However, it should be noted that the sleep disturbance among astronauts aboard the ISS is often attributed to noise, confinement and stress, and it abates over time post-flight. Additionally, both SF and PD present with similar changes in the gut microbiome, with overall dysbiosis and a decrease in short chain fatty acid synthesizing bacteria28. Thus, while spaceflight impacts share some physiological similarities with PD, many of the effects of space flight are temporary, while the degenerative trajectory of PD is usually irreversible and thus requires further research on intervention measures to mitigate any risk of permanent damage during exploration mission.

Systemic inflammation

Neutrophil to Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is regarded as a hallmark biomarker for systemic inflammation and stress, and there is a significantly increased NLR, due to increase in neutrophil count and lower lymphocyte counts in PD patients, throughout the disease course29. SF leads to an increase in NLR among astronauts, however, it reverts within a week after landing30.

Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS) pathway analysis post SF viewed through lens of PD

Since MD, and OXPHOS dysregulation are key hallmarks of PD31, we analyzed OXPHOS genes differentially regulated post-SF in relation to PD and other neurodegenerative pathways.

Methods

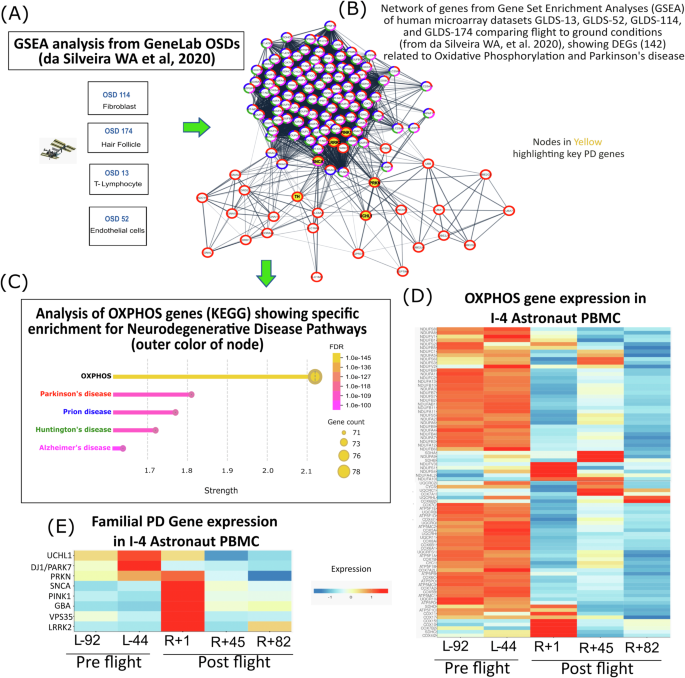

Using GSEA data (in vitro human cells) from GeneLab OSDs-13 (lymphocyte), -52 (HUVEC), -114 (Fibroblasts) and -174 (hair follicles) (Fig. 1A), comparing flight to ground treatment as published23, we reanalyzed the gene sets related to the OXPHOS cluster and PD node in Cystoscape (v3.10.1) (Fig. 1B). Edges are shown in confidence view with active interaction sources from experiments, databases, co-expression, neighborhood, gene fusion and co-occurrence32 (interaction score > 0.4). Nodes were modified as individual gene names with outer color representing genes overlapping in other neurodegenerative disease: Red- PD, Blue- Prion disease, Green- Huntington’s disease (HD) and Pink- Alzheimer’s disease (AD). To emphasize the overlap of OXPHOS genes with PD we performed a String (v12.0) enrichment analysis of all enlisted OXPHOS human genes (from KEGG pathway: ko00190) showing specific functional enrichment for listed neurodegenerative disease pathways (color coded as Fig. 1B) with corresponding false discovery rate (FDR) values, strength and the count of associated genes in each disease (Fig. 1C). From the list of OXPHOS genes altered in PD, we investigated their expression in the Inspiration 4 (I-4) mission astronaut blood PBMC transcriptomics data during pre and postflight, using the Inspiration4 Multiome Data Explorer, PBMCs33,34 (Fig. 1D). We further investigated the expression of key familial PD genes such as PRKN, PINK1, UCHL1, LRRK2, DJ1, VPS35, SNCA and GBA in the I-4 astronaut blood PBMCs (Fig. 1E).

A Data sets reanalyzed from GeneLab (OSDs-13, 52, 114, 174) used for GSEA analysis by da Silviera W.A. et al.23. B Network of PD genes from OXPHOS node with outer color representing participation in following diseases from KEGG pathways: Red- PD, Blue- Prion disease, Green- Huntington’s disease (HD) and Pink- Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Key familial PD genes highlighted in yellow. Edges shown in confidence view with active interaction sources from experiments, databases, co-expression, neighborhood, gene fusion and co-occurrence32 (interaction score > 0.4). C Enrichment analysis of OXPHOS genes using String database (v12.0) showing specific functional enrichment for PD, Prion, HD and AD along with their false discovery rate (FDR) values, strength and gene counts. D Expression heatmaps for PD related OXPHOS pathway genes in I-4 astronaut blood PBMCs showing downregulation postflight compared to preflight. E Key familial PD gene expression altered in I-4 astronaut’s blood postflight. All I-4 data were generated from Inspiration4 Multiome Data Explorer, PBMCs22,23. Flight timeline denoted as L= Launch or R=Return followed by the number of days.

Results

OXPHOS pathway genes are altered post SF and in PD (Fig. 1A, B). Based on the Strength and FDR values post String enrichment analysis of the human OXPHOS genes, PD showed the highest enrichment effect and significance (FDR 3.42e-111) followed by Prion disease (FDR 2.14e-108), HD (FDR 1.95e-105) and AD (FDR 1.63e-100), emphasizing that alteration in OXPHOS pathway could not only lead to PD but also other neurodegenerative diseases (Fig. 1C). Additionally, we found, PD related OXPHOS pathway genes were found to be downregulated in the I-4 astronaut blood PBMCs with a sustained decrease even after 82 days post return (R + 82) (Fig. 1D). Interestingly, familial PD genes such as PRKN, PINK1, UCHL1, LRRK2, DJ1, VPS35, SNCA and GBA exhibited altered expression immediately after return (R + 1) with sustained changes persisting even months post recovery (R + 82) compared to preflight levels (Fig. 1E).

Discussion

Mitochondrial dysfunction in PD and SF

Extensive research on astronauts and animals has revealed that exposure to SF stressors can lead to accelerated aging, central nervous system impairments, and systemic MD35. A landmark multi-omics study involving data from 59 astronauts and space-flown mice revealed that mitochondrial stress is a key hub for driving systemic changes contributing to health risks post SF23. Data from the NASA Twin Study on long term space missions demonstrated increased mitochondrial stress and higher levels of mitochondria in the blood, both signs of MD23,36.

MD in PD results in increased mitochondrial DNA damage and ROS; dysregulation of bioenergetic capacity by OXPHOS downregulation, quality control, fusion-fission dynamics, and mitochondrial transport. These aberrations lead to the activation of cell death pathways31,37,38,39,40. Systemic MD is observed in PD patients’ SNpc; as well as in muscle and blood (lymphocytes and platelets)31,40. This systemic MD mirrors observations seen post SF23.

Our analysis of the I-4 astronaut PBMC transcriptomics data reveals a sustained downregulation of PD-related OXPHOS pathway genes. Although the I-4 astronauts had a short stay of only three days in space, they traveled farther than the ISS or Hubble, reaching a distance of 585 km experiencing increased radiation exposure, which may result in impairment of mitochondrial OXPHOS Complex I41 causing this prolonged MD.

Proteostasis and Ribostasis failure in PD and SF

Systemic failure in both proteostasis and ribostasis have been inferred post-SF by alterations in ribosome assembly, mitochondrial function, and cytosolic translation pathways23. Emerging evidence from Drosophila and human induced Dopaminergic neurons suggests a link between MD and proteostasis failure involving the PINK1/Parkin pathways42. Age-related neurodegenerative diseases including PD also manifest proteostasis and ribostasis failure in patients43.

Similarities with other neurodegenerative disorders

While the increased risk to astronauts of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and dementia are being studied44,45, to our knowledge this is the first evidence of PD related-marker gene alterations in humans linking PD and SF. Because there are molecular similarities between PD and other neurodegenerative disorders such as AD and HD (Table 1, Fig. 1) more research is needed to establish a specific link to PD. This is challenging because PD and related diseases, collectively referred to as Parkinsonism, share common cardinal movement symptoms but are heterogeneous in their molecular signatures, such as presence or absence of Synucleinopathy1. Although the presence of alpha synuclein inclusions post space-flight has not been investigated, it has been reported that 6 months after exposure to Galactic Cosmic Radiation (GCR) there was an increase in Aβ plaque accumulation and cognitive impairment in an AD mouse model45.

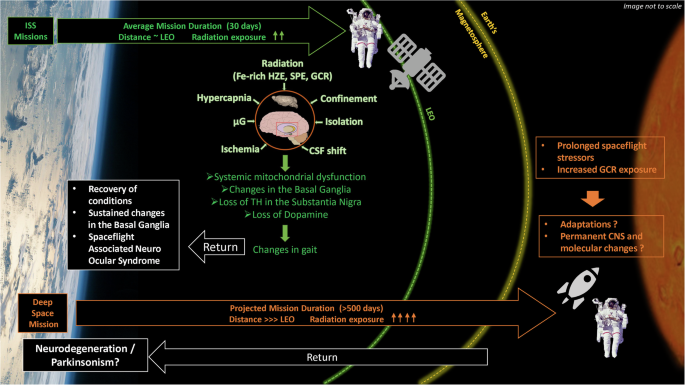

We hypothesize (Fig. 2) that the stressors of SF may consistently lead to systemic MD23 and elevated inflammation30 resulting in structural changes in the BG6,8, loss of TH in the SN, and decreased DA neurotransmitter5,15,25—which may produce a temporary altered gait, posing a risk of permeance during prolonged space missions12. However, other regions of the brain exhibit greater plasticity and may return to normal function several months after SF7. Nevertheless, the sustained changes in the BG, which includes the SNpc and Str, may pose a yet not clinically encountered risk of PD to astronauts for developing movement disorders during and post prolonged deep space travel. These brain regions house the most vulnerable neurons, the degeneration of which underlies at least two neurodegenerative movement disorders: PD40 and HD46.

Post SF there is a sustained increased in the Basal Ganglia (BG) volume several months post-SF, loss of Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) gene expression and Dopamine neurotransmitter levels in the Substantia Nigra pars compacta and Striatum, and systemic mitochondrial dysfunction with PD pathway genes affected. These molecular and physiological changes in the Central Nervous System (CNS) may lead to the observed PD-like changes in gait and muscle loss, which fade over time upon return. However, there are some sustained changes such as SANS and changes in the volume of BG. While the average mission duration at the ISS is about a month, a round-trip mission to Mars without landing would likely take around 500 days. For such deep space missions beyond LEO and Earth’s magnetosphere, radiation exposure increases dramatically, which could lead to permanent damages in the CNS with neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinsonism. (Credits: The image includes elements obtained and modified from Wikimedia Commons such as the “Earth’s cloudscape over the Philippine Sea” from NASA, “Mars: The Red Planet” by Madhav fallusion, and “Bruce McCandless II during EVA in 1984” from NASA.

Limitation of the study

While this study draws parallels between neurodegenerative changes seen in PD and SF, several limitations should be considered. In microgravity, humans undergo a series of adaptive responses, many of which mirror hormesis—the process through which low-level stressors can trigger beneficial adaptations47. For example, changes in mitochondrial function and muscle atrophy may improve metabolic efficiency in microgravity, reducing energy expenditure and making bodily functions more suited to a low-gravity environment48. Similarly, adaptations in gait and balance in astronauts are reversed with neuromuscular and neurovestibular retraining after the return to Earth. OD is primarily due to CNS fluid shifts and reverses once astronauts return to normal gravity. By clearly separating these adaptation-driven changes from the progressive, irreversible nature of PD, we recognize that while analogies can be made, the mechanisms and outcomes may differ, requiring further longitudinal research. Such longitudinal research would allow us to better differentiate between temporary adaptive responses and any long-term neurological or physiological consequences. This would be particularly valuable in evaluating if and how spaceflight-induced adaptations could inform our understanding of PD and potentially contribute to preventive strategies or therapies in neurodegeneration research. Although the associated risk of PD is justified here, the absence of widespread PD reports among astronauts could be due to several factors: astronauts are rigorously selected for good health, and post-flight changes often revert to normal, particularly with the short duration of current missions within LEO. Additionally, while there are reports of other diseases among astronauts, comprehensive studies specifically focused on the incidence of PD in this population are lacking.

Conclusion

The list of analogous features (Table 1) are not intended as a diagnostic, but shows that the concerns raised in this paper extend to other neurodegenerative disorders with overlapping symptoms. The parallels between SF and Parkinsonism raise significant concerns that deserve clinical vigilance regarding the development of Parkinsonism-like conditions during prolonged deep space missions. While some shared characteristics may resolve over time, the risk of any significant neurological degradation of performance on long duration missions is potentially catastrophic. As humanity sets its sights beyond LEO to the Moon and Mars missions23, it is imperative to understand and mitigate these neurological hazards.

Given the absence of a cure for PD, preventive measures are essential to safeguard space explorers. Proactive antioxidant therapy30 and mitochondrial protections are sensible, considering the link

between MD and PD. Studies focusing on mitochondria-targeted therapies (pre and during SF) would help mitigate these concerns19,23. Furthermore, emerging evidence suggests that α-synuclein seed amplification assays (SAAs) may enable the early diagnosis of PD, years before the onset of classical symptoms and significant neuronal loss in the SNpc27. Recently a diagnostic tool has been reported for detection of phosphorylated α-synuclein from skin biopsies of individuals affected with Synucleinopathy such as PD, Multiple System atrophy, Lewy body dementia and pure autonomic failure49. Monitoring these changes could allow astronauts to assess the potential risk of PD and related disorders.

PD may represent a potential long-term health concern for astronauts on and after exploration space missions. Understanding the interplay between SF stressors, MD, and PD could help mitigate damage, and benefit those on Earth who are affected by, or at risk for, PD.

Responses