Spatial segmentation of Jiali Fault’s Holocene activity in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau

Introduction

Tibetan Plateau is recognized as the region with the most active tectonic movements globally1,2,3. Since the late Cenozoic, the primary deformation of the plateau may be regulated by the deformation of several major strike-slip faults4,5,6,7,8,9. In southeastern Tibetan Plateau, a strike-slip shear system exists around the Eastern Himalaya Syntaxis (EHS)10,11,12,13. These strike-slip faults may have accommodated the eastwards movement caused by the extension of the central plateau14,15,16,17,18, which has led to complex crustal deformation and intense seismic activity in the southeastern Tibetan region19,20,21. Moreover, owing to the abundant mineral and hydroelectric resources, this region boasts a dense population and extensive engineering activities22,23. Consequently, accurately assessing the Holocene activity of strike-slip faults is crucial for analysing regional seismic hazards.

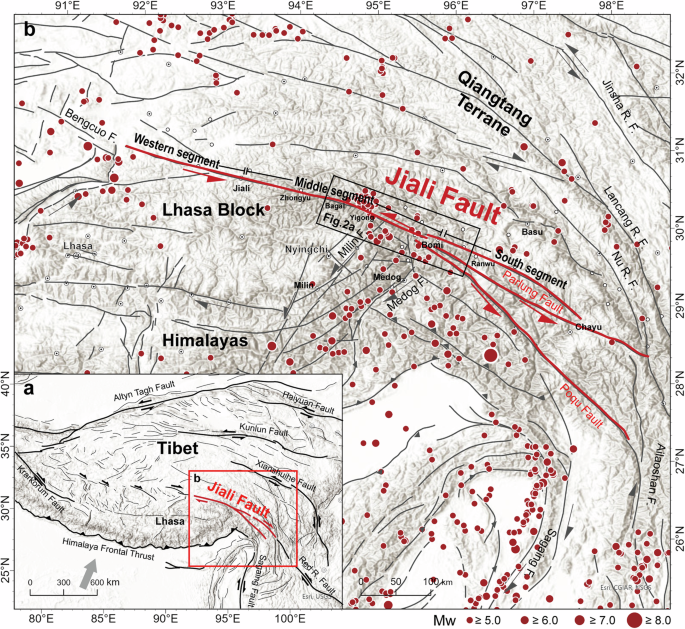

The Jiali Fault, a right-lateral strike-slip fault in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau, plays a crucial role in accommodating crustal deformation of the plateau24,25,26,27,28,29 (Fig. 1a). It defines the boundaries of the EHS10 and is considered the best target for analysing the tectonic movements and crustal deformation processes of the southeastern plateau12 (Fig. 1b). However, it remains controversial whether the Jiali Fault was truly active in the Holocene. Owing to the significant linear landform shaped by the Jiali Fault, numerous researchers have investigated its Holocene activity through remote sensing interpretation and field surveys26,30,31,32,33,34. Armijo et al.26 proposed that the Jiali Fault and other strike-slip faults were active in the Holocene on the basis of remote sensing and geomorphic observations. However, Shen et al.31 verified the geomorphological markers discovered by Armijo et al.26 and attributed their origin to the frost heave effect rather than seismic activity. The poor development of river terraces in Yigong and Parlung valleys has led to the long-term absence of Quaternary geomorphological markers20,26,35, which suggests that the Jiali Fault may have been inactive31,36,37 or exhibited a relatively low rate of activity30,33 in the Holocene. But the inactivity of the Jiali Fault does not align with the rapid strike-slip rates calculated via GPS, which may reach 10–20 m/y, according to numerous studies18,19,28,32. Furthermore, the inactivity of the Jiali fault also contradicts the frequent earthquakes38. The right-lateral strike-slip motion of the Jiali Fault is responsible for generating periodic earthquake swarms39. Therefore, it is necessary to re-examine the Holocene activity of the Jiali Fault.

a Location of the Jiali Fault. Black solid lines represent fault traces derived from Tapponnier et al.25. The red rectangle indicates the extent of Fig. 1b. b Jiali Fault and the active faults in southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Major fault traces (black lines) are obtained from the China Active Faults Database (CAFD)90 Wu et al. The red circles indicate earthquakes with magnitudes greater than 5.0 that have occurred since 1900. The earthquake catalogs compiled in this analysis are available at U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Science Base93. The map background shows the World Hillshade of the study region derived from the Esri in ArcGIS Online. The black rectangle marks the location of Fig. 2a.

The potential activity of the Jiali Fault could have a profound impact on the surrounding urban safety, large railway, and hydropower projects23,40,41. Therefore, determining whether the Jiali Fault was active in the Holocene is important. In this study, we provide evidence of Holocene activity in the middle segment of the Jiali Fault via 14C dating. This information is highly important for potential earthquakes and the active geodynamic processes of the structures in southeastern Tibetan Plateau.

Results

Geomorphological analysis

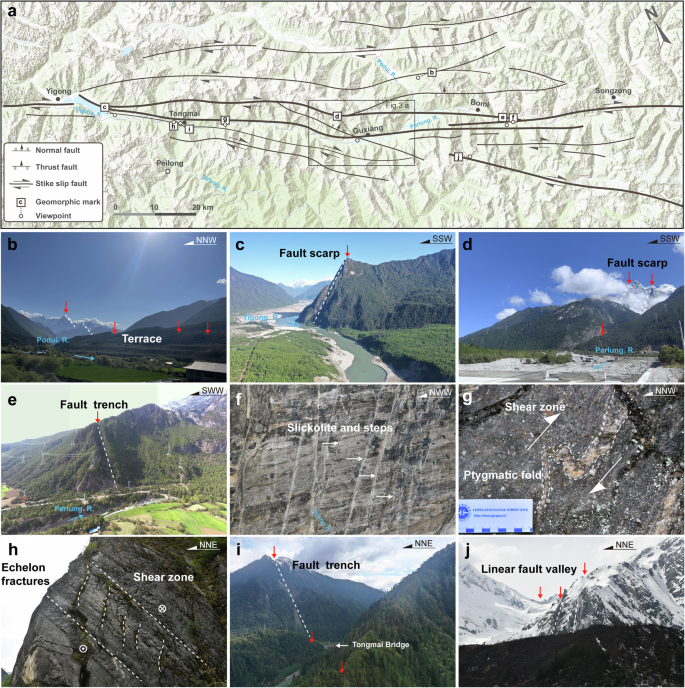

Regional faults are typically composed of numerous secondary faults with highly complex fault traces42. On the basis of remote sensing imagery and existing research34,43,44, a preliminary estimation of the Jiali Fault traces was made (Fig. 2a). In field surveys, key attention has been given to geomorphological markers, such as fault scarps, fault trenches, outcrops, and linear fault valleys, with detailed locations and photographs shown in Fig. 2b–j. Multiple fault scarps and trenches exhibiting similar right-lateral displacements were discovered, providing crucial foundational data for determining the traces of the Jiali Fault. For example, in the Podui river valley, the linear landforms formed by high terraces and fault scarps on nearby mountains are parallel to the strike of the Jiali fault (Fig. 2b). A series of fault scarps near Yigong Lake and Guxiang Lake reveal the strike of the main Jiali fault (Fig. 2c, d). In eastern Bomi city, a prominent fault trench in the same direction was also identified (Fig. 2e). On the outcrop within the fault trench, distinct slickolites and steps are visible (Fig. 2f). Moreover, typical outcrops were identified to reveal right-lateral strike-slip motion. Near the Chalung Gully, under the influence of dextral motion, quartz veins have deformed into ptygmatic folds (Fig. 2g). Near Tongmai Bridge, echelon fractures indicate dextral strike-slip movement (Fig. 2h). Some field survey sites that have been reported12,33,34, such as the fault trench near Tongmai Bridge (Fig. 2i) and the fault valley in Galong La (Fig. 2j), were re-examined during this investigation. On the basis of these indications, the traces of the Jiali Fault were further corrected, and a second field check was conducted.

a Fault traces of the Jiali Fault from Yigong to Songzong town. Fault traces are obtained from seismotectonic maps of China and adjacent regions43, the geological structural database of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau44 and the China Active Faults Database (CAFD)90. The map background shows the World Hillshade of the study region derived from the Esri in ArcGIS Online.; b–g typical fault landforms; b fault scarp near the Yigong barrier lake; c fault trench near Tongmai Bridge; d fault scarp near the Guxiang barrier lake; e fault trench near Bomi city; f linear landforms on the Podui River terrace; g linear fault valley near Galong La; h–j fault outcrops; h Shear zone and echelon fractures near Tongmai Bridge; i shear zone and ptygmatic fold near Tianmo Gully; j Slickolite and steps at the outcrop in eastern Bomi, revealing right-lateral strike-slip motion.

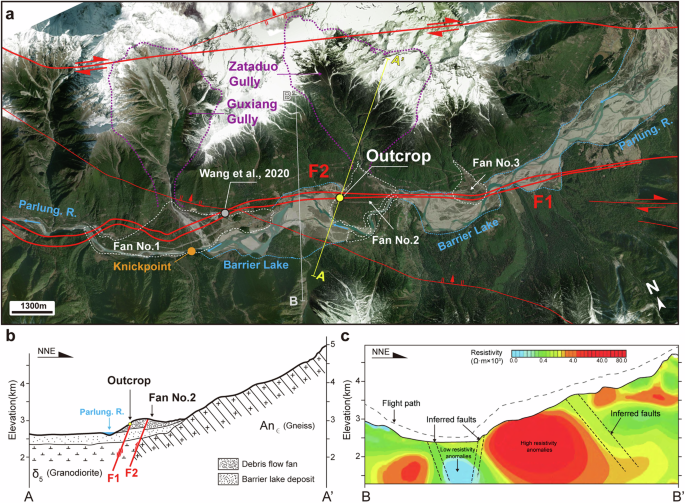

The focus of the second field survey was to search for evidence of the Jiali Fault or its secondary faults traversing Holocene strata. Temperate glaciers are widely distributed in the middle segment of the Jiali Fault (Jiali–Bomi)45. Melting produces water from these glaciers, which often causes mudslides in summer owing to solar radiation and heavy rainfall46. Giant debris flows block the Parlung River, forming barrier lakes47. The Guxiang Gully is a typical glacial debris flow gully in the area (Fig. 3a). Hanging glaciers are widely distributed upstream of this gully, and copious moraines can cause debris flows triggered by runoff generated by rainstorms and meltwater from glaciers deposited in this gully. Large debris flows have repeatedly erupted in the Guxiang Gully (1953, 1964, 1973) and blocked the Parlung River48. Therefore, Quaternary sediments, such as river deposits and barrier lake deposits, have developed in the valley above the Guxiang knickpoint (Fig. 3a, approximately 2600 m), providing good geological conditions for verifying the activity of the Jiali Fault.

a Satellite imagery of the outcrop site; the location is shown in Fig. 2a. Satellite imagery is derived from Google Earth. The yellow points represent the outcrop sites in this study. The blue dashed line represents the barrier lake. The white dashed line delineates the extent of the debris flow fans, within which there are three such fans. The outcrop site that we found is located on the No. 2 debris flow fan, formed by debris flow materials from the Zataduo Gully. b Profile A-A’ through the outcrop site. The location of the profile is shown in Fig. 3a. The digital elevation model is derived from the ASTER GDEM94. c Aeromagnetic profile B-B’ near the outcrop site. the aeromagnetic data is derived from Luo et al.49. The location of the profile is shown in Fig. 3a.

Following a detailed field investigation, we identified two major debris flow fans and one smaller debris flow fan in the Guxiang area. The first fan (Fan No. 1 in Fig. 3a) was formed by debris flows from the Guxiang Gully, whereas the second fan (Fan No. 2 in Fig. 3a) was created by debris flows from the Zataduo Gully (Fig. 3a). The third fan (Fan No. 3 in Fig. 3a) is relatively small. Wang et al.20 identified a surface rupture point near the No. 1 debris flow fan, with dating constraining fault activity to the 2680–2160 a B.P. A more detailed fault distribution map (Fig. 3a) indicates that two branches of the Jiali Fault, F1 and F2, in the Guxiang area extend along the Parlung Valley, which is consistent with the findings of Wang et al.20. Single outcrops and the characterization of satellite images cannot directly explain the Holocene activity of the Jiali Fault. More plausible evidence is needed to prove that the Jiali Fault has experienced movement since the Holocene. Therefore, possible linear geomorphic features showing migration and new fault outcrops along the migration indicators were explored.

Satellite imagery reveals that both F1 and F2 traverse the No. 2 Fan. Consequently, we conducted a more detailed investigation of the No. 2 Fan. Initial observations of the terrain indicated that the location of the highlands did not seem to match the profile of the river terrace. Research by Zeng et al.49 suggested that this highland was formed by debris flow deposits within the Zataduo Gully, and drilling results from Meng et al.50 indicate that the No. 2 Fan was deposited on the first terrace of the Parlung River (Fig. 3b). The results of nearby geophysical surveys51 can also be used to infer the approximate strike of the Jiali Fault and its relationship with the debris flow fan (Fig. 3c). Fortunately, the best evidence of Holocene activity along the Jiali Fault was found on the No. 2 Fan (29° 54’ N, 95° 28’ E), which is an ancient seismic indicator of F1 traversing recent sediments. This evidence was found in the sediment on a cleaned steep slope on the northeast side of the G318 highway. Next, we conducted a detailed analysis of the outcrop.

Sediment deformation analysis

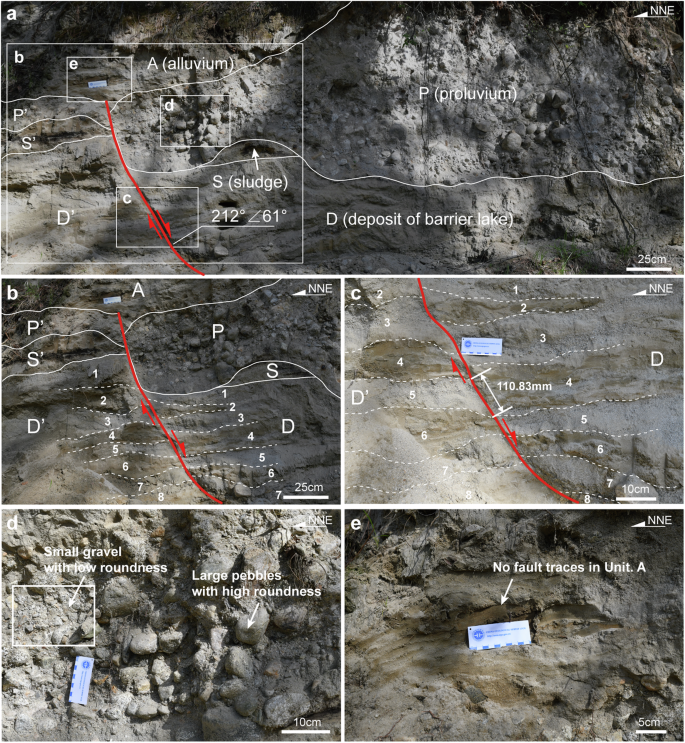

An outcrop was found approximately 10 m northeast of the G318 highway on the No. 2 debris flow fan. The exposed sediment of the outcrop can be divided into two parts. The lower part is mainly composed of fine sand, which is consistent with sedimentation in a barrier lake. The upper part is composed mainly of pebbles and gravel, which are indicative of debris flow deposits. The outcrop clearly indicates that the Jiali Fault has ruptured the Holocene sediments.

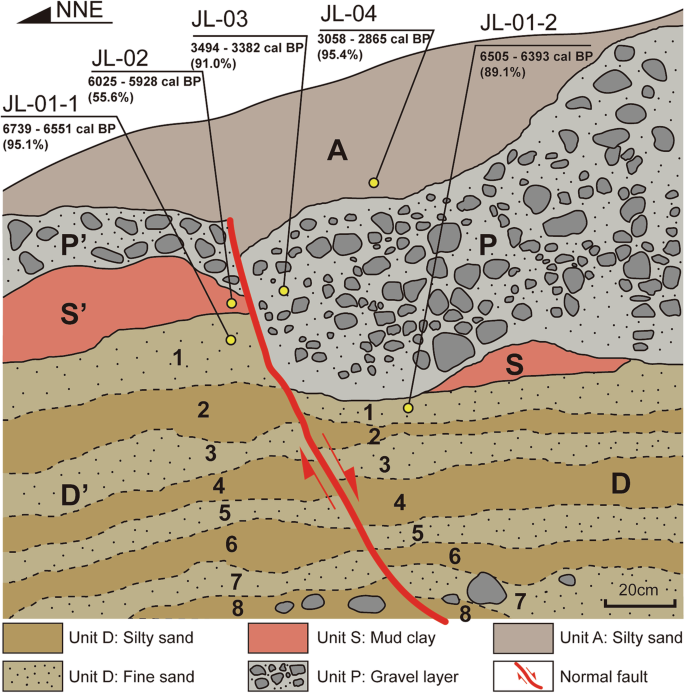

The outcrop reveals four stratigraphic units (D, S, P, and A, from bottom to top), as shown in Fig. 4 and Table 1 (letters indicate units). The NW–SE-trending normal fault crosses a fine sand layer with rhythmic bedding (D), a mud clay layer (S) and a gravel layer (P, debris flow deposits) and is then covered by a later-deposited sand layer (A, fluvial deposits) (Fig. 4b). This is a secondary branch fault of the Jiali Fault, designated F1, whose strike (122°) is parallel to the main fracture (Fig. 3a). Typically, large strike-slip fault zones comprise a series of secondary faults that are nearly parallel to the main fault zone. The dip angle of F1 is 61°. Consequently, we consider the activity of F1 to represent the activity of the Jiali Fault. The geological characteristics of the units and the relationships between the units and the Jiali Fault are described from the bottom layer to the top layer.

a Panorama photograph of the outcrop; the white dashed box indicates the position of subsequent photographs c–e. b Details of the position of fault deformation. c Details of the deformation and fracturing of the silty sand layer and the fault distance. d Details of unit P. Small gravel clasts have low roundness, and large pebbles have high roundness. e Details of unit A, which is not crossed by a fault.

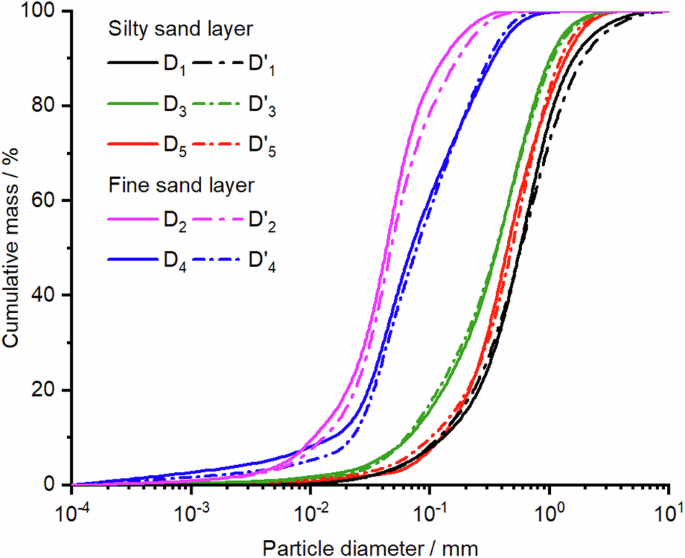

Unit D is the lacustrine deposit of the Guxiang barrier lake; it is a rhythmic layer formed by yellowish brown silt and fine sand. From top to bottom, the rhythmic layer is divided into eight subunits. The subunits are numbered D1, D3, D5, and D7; they are fine sand, whereas the subunits that are numbered D2, D4, D6, and D8 are smaller silty particles. The fault divides unit D into two parts: hanging wall D and footwall D’. Rhythmic sedimentation within the hanging wall and footwall of the fault have a corresponding relationship. To accurately assess the corresponding relationship of each subunit, we collected several samples from units D1 to D5 and analysed the particle size characteristics of the gravel via a laser particle size analyser (Better Size 2000) (Fig. 5). A similar grain size distribution curve can be used to determine the corresponding relationship between the subunits of hanging wall D and footwall D’ and thus confirm the characteristics of fault movement52. The hanging wall of the fault evidently moves down by approximately 110 mm (Fig. 4c). The sedimentary layer near the fault shows strong shear deformation, such as curved bedding. In the hanging wall, the bedding angle of the silty sand layer, which is generally horizontal, sharply increases.

Grain size distribution curve of the deposits in the Jiali Fault outcrop.

Unit S is also the lacustrine deposit of the barrier lake in Guxiang, and the unit is a greyish brown mud clay. However, owing to significant alteration by subsequent proluvium, no corresponding S’ was found near the fault plane; instead, a portion of S’ was discovered in the hanging wall, approximately 40 cm away from the fault plane. Although it is uncertain whether the fault breaks unit S, it is certain that unit S has been modified by unit P.

Unit P is a gravel layer that is not highly rounded. The smaller gravels exhibit very low roundness, whereas the larger pebbles have better roundness, but their long-axis orientations are also not uniform (Fig. 4d). The content of loose soil is greater than that of the floodplain sediment of the Parlung River. Consequently, unit P is a proluvium. The deposition of unit P has modified the upper part of unit S and unit D’ (D’1–D’2). The thickness of unit P decreases in the NNE direction, resulting in a small exposed area of P’, making it difficult to estimate deformation on the basis of the distance between P and P’. However, it is still possible to observe that the fault has traversed unit P. Overlying unit A is a silty sand layer, and its basement contact surface is not deformed. No fault crossing unit A was observed directly onsite (Fig. 4e). In unit A, the fault gradually becomes undetectable. This indicates that the earthquake event occurred between units A and P.

Importantly, this profile is not a fake fault due to gravity collapse, which is commonly observed in slopes composed of lacustrine sediments. Two pieces of evidence corroborate the reliability of the fault. First, a key characteristic of the fake fault is that the lowest unit remains undeformed, as clearly shown in Fig. 4a, where the units at the base of the outcrop are still intersected by F1. Second, fake faults typically occur on high slopes with large dips, whereas the outcrops that we observed do not exhibit such elevated slopes in the SSW direction. In gently sloping terrain, it is difficult to generate deformation caused by gravity collapse, even in weak lacustrine sediments. Therefore, the vertical offset in this outcrop should be of tectonic origin.

The age of the sediments in the outcrop was determined by 14C to obtain the approximate time of this event. The 14C samples were collected from D1 (JL-01), S (JL-02), P (JL-03), A (JL-04) and D’1 (JL-05). As shown in Table 2, the 14C dating results were consistent with the stratigraphic sequence displayed in the outcrop. The dating results for the same units, D1 and D’1, are very close, which proves that using the results of particle size testing to determine the corresponding relationships among the sand layers is accurate and reveals the direction of fault deformation. The 14C dating results indicate that the earthquake event occurred in the period from 3494 to 2865 cal B.P. (Fig. 6). This event was older than that reported by Wang et al.20. This may be related to multiple seismic events. However, further research is needed with the discovery of additional outcrops.

The stratigraphic contacts are shown via black lines, and the dashed lines represent rhythmic bedding. The red lines represent faults. The yellow points represent the 14C samples.

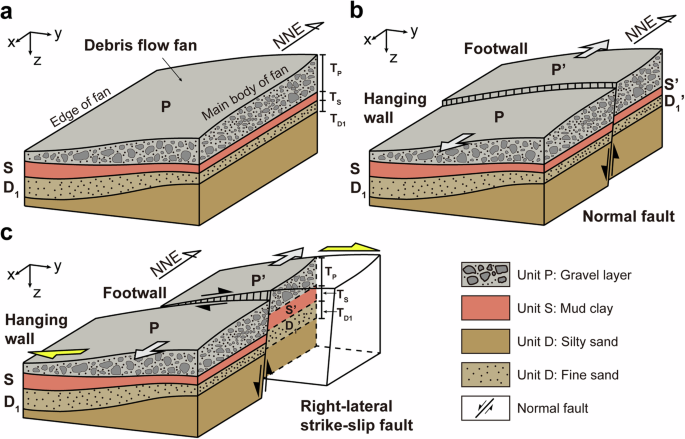

Motion sense analysis

The characteristics of right-lateral strike-slip movement along the Jiali fault are significant12,18,20, as evidenced by the outcrops discovered in this study. The outcrops clearly exhibit a sense of normal motion, but this is not the sole mode of motion along F1. Notably, the different thicknesses of units P, S, D1, etc., on both sides of the fault plane clearly indicate that in addition to vertical offset, there should be significant right-lateral strike-slip displacement. The identified outcrop is located at the boundary between the debris flow fan and the dammed lake. We reconstructed the prefailure bedding of the sediments (Fig. 7a). The thickness of the debris flow deposits (unit P) decreases farther away from the main body of the debris flow fan, whereas the thickness of the dammed lake deposits (units S and D1) increases correspondingly. Moreover, the thickness of P (Tp) decreases in the direction of debris flow movement, whereas the thicknesses of S and D1 (TS and TD1) remain unchanged.

a Variations in the thickness of sedimentary deposits at the edges of debris flow fans, without displacement; b: normal fault, which does not alter the thickness of sediments on either side of the fault plane; c only when right-lateral strike-slip displacement occurs can it lead to a reduction in the thickness of the downwards-thrown unit P while simultaneously increasing the thicknesses of units S and D1. Tp represents the thickness of unit P, Ts represents the thickness of unit S, and TD1 represents the thickness of unit D1.

To facilitate the description of the variation in sediment thickness, a simple coordinate system was established, as shown in Fig. 7a, where the x-axis represents the direction of debris flow movement, and the y-axis represents the direction perpendicular to it. In the x direction, Tp decreases, whereas TS and TD1 remain unchanged. In the y direction, Tp increases, and TS and TD1 decrease. If F1 is a typical normal fault (Fig. 7b), it does not alter the thickness of sediments on either side of the fault plane53. In the outcrop, the thickness of unit P in the hanging wall should be less than that of P’ in the footwall, whereas the thicknesses of S and D1 should be approximately equal. However, the thickness of P’ in the footwall is significantly less than that of P in the hanging wall, whereas the thicknesses of S’ and D1’ in the footwall exceed those of the corresponding layers in the hanging wall (Fig. 4a). This finding indicates that the footwall experienced horizontal displacement opposite of the y-direction, leading to an increase in the thickness of the dammed lake sediments and a decrease in the thickness of the debris flow deposits (Fig. 7c). The thickness variations in the sediments substantiate that F1 is a right-lateral strike-slip fault with normal displacement. Although no linear landform caused by strike-slip faults has been found on the surface due to the deformed sediment cover produced by the undeformed unit A, the results are sufficient to indicate that the middle section of the Jiali fault underwent strike-slip motion in the Holocene. In summary, the displacement of sedimentary rhythmites caused by palaeoearthquakes is compelling evidence, strongly supporting the activity of the Jiali Fault during the Holocene.

Differences in Holocene activity

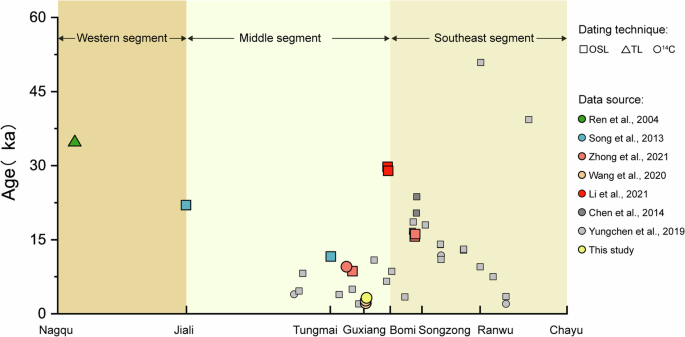

Previous studies have divided the Jiali Fault into three segments on the basis of its spatial distribution (Fig. 1b): the western segment runs from Kamanie southeast of Nagqu to the Jiali area northwest; the middle segment runs from the Jiali area to the Bomi area; and the southern segment runs from the Bomi area to the Zayu area southeast. In the southern segment, there are two branches: the Parlung Fault in the north and the Poqu Fault in the south30,33,35. Previous studies have investigated the activity of different segments of the Jiali Fault. Combined with published dating results, the characteristics of Holocene activity of the Jiali Fault were discovered to have obvious spatial segmentation (Fig. 8).

The grey and light grey points represent the ages and locations of terrace sediments that have not been deformed by the fault (data from Chen et al.55 and Yungchen et al.56). The points with different colours are the ages of surface-rupturing palaeoseismic events determined in this study and previous studies (data are from references20,30,33,34,54,55,56,88). Different shapes of points represent different dating methods.

In the western segment of the Jiali Fault, the older fault is buried by dated and undeformed sediments. The age of the sediment is approximately 34.7 ± 2.71 ka (Fig. 8)30, which was determined via thermoluminescence (TL) dating. In southern Jiali District, the age of the undeformed glacial lacustrine sediments is approximately 22.0 ± 1.8 ka (Fig. 8)33, which was determined via optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating. Because the western segment of the Jiali Fault is located mainly along the valley of the Yigong River, river terraces are not developed. This leads to a lack of young geomorphic features and sediments that can preserve evidence of Holocene deformation. Therefore, the Holocene activity of the western segment is not significant37,54.

In the middle segment of the Jiali Fault, the activity clearly differs. On the east side of the Tungmai Bridge, the age (OSL) of the river terrace gravel layer disturbed by the fault is 11.06 ± 0.94 ka. Evidence from Guxiang Lake has shown that the Jiali Fault passes through the Holocene alluvial proluvial fan20. The ages of the sediments disturbed by the fault are approximately 2.160 ± 0.030 and 2.680 ± 0.030 ka, as determined by 14C dating. Combined with the dating results in this study, the Holocene activity in the middle segment of the Jiali Fault is concluded to be significant.

In the southern segment of the Jiali Fault, near the Galong La Temple south of Bomi District, the ages (OSL) of moraines disturbed by the fault are 28.96 ± 2.60 and 29.74 ± 2.54 ka (Fig. 8)54. On the river terrace of Songzong town, two palaeoseismic events are revealed by the landform and deformation of late Quaternary lacustrine sediments, with time limits of 16.1 ± 1.06–15.66 ± 0.92 a (OSL) and 8630 a ± 60 a–9561 a ± 37 a B.P. (14C)34. Chen et al.55 and Yungchen et al.56 also conducted extensive dating work on terrace sediments that were not affected by fault deformation (Fig. 8). Their results revealed no evidence of Holocene activity.

In general, the results of the field survey and sediment dating indicate that the middle segment of the Jiali Fault was more active than the adjacent segments during the Holocene.

Discussion

The differences in the Holocene activity of the Jiali Fault may be attributed to continued northeastwards compression of the northeastern corner of the Indian Plate57,58. The lithosphere around the EHS bears the main N–S/NNE–SSW compressive and vertical extension stresses59,60. The continuous convergence of the plate margins caused the lower crust of the Indian Plate to thrust northwards61,62. Deep subduction of the front edge of the Indian margin resulted in strong folds, thrusting, and crustal thickening63,64. As a rigid block, the EHS is being torn from the main Indian Plate and is rotating clockwise relative to the Indian Plate65. Simultaneously, the Jiali Fault has served as a crucial boundary fault regulating southeastwards compression during the late Cenozoic25. Part of the eastwards movement of central Tibetan Plateau was transferred to the eastern Himalayan syntaxis and surrounding faults66. The right-lateral strike-slip movement of the Jiali Fault balances the eastwards movement from central Tibetan Plateau7. Moreover, the movement and local uplift of the middle and southern sections of the Jiali Fault regulate the rotational deformation of the EHS10. Furthermore, tectonic forcing has altered the hydrological systems and geomorphology of the region57. Therefore, the activity of the middle segment of the Jiali Fault is more pronounced than that of the other segments. This conclusion is supported by the eastwards migration of crustal deformation in central Tibetan Plateau19, the movement of the crustal deformation centre from the eastern Himalayan syntaxis to the Jiali Fault67 and the notable concentration of stress within the Guxiang–Tongmai segment of the Jiali Fault68.

Owing to the lack of definite records of major earthquakes20 and the absence of sediments caused by rapid erosion26, the understanding of the rupture behaviour of the Jiali Fault is quite limited, which is crucial for comprehending seismic activity in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. The 1950 Mw 8.6 Chayu/Assam earthquake was once believed to be associated with this fault69. However, recent research has shown that this earthquake was caused by the main Himalayan frontal thrust70. The focal mechanism solution and location of the 2017 Mw 6.9 Milin earthquake indicate that the seismogenic fault is the Xixingla Fault71,72,73. Although no large earthquakes have been directly recorded, the results of reported studies on the Holocene activity of the Jiali Fault have revealed that at least five earthquakes have occurred on the Jiali Fault since the Holocene. Song et al.33 identified a moraine truncated by a fault near Galong La, estimating the timing of this event to be 650 a B.P. Wang et al.20 discovered that the Jiali Fault had offset a barrier lake and fluvial–lacustrine deposits near Guxiang Lake, identifying two events dated to 2160 ± 30 and 2680 ± 30 a B.P., as determined by 14C dating. Zhong et al.34 identified a Holocene event along the Jiari Fault on the basis of 14C and OSL dating results of earthquake-induced soft sediment deformation in lacustrine deposits, with the event occurring between 9561 ± 37 and 8630 ± 600 a B.P. Considering the timing of these results and the palaeo-earthquake events discovered in this study (3494 to 2865 cal B.P.), it is speculated that the period of earthquakes on the Jiali Fault in the Holocene may have been 1.5–3 ka. Certainly, the current data remain insufficient for an accurate assessment of the Holocene slip rate and the major earthquake period of the Jiali Fault. However, the seismic hazard presented by the Jiali Fault, which is a potential seismic zone73, deserves further attention.

Although no recorded major historical earthquakes have occurred, Mw <5 earthquakes near the Jiali Fault have been frequent73,74,75 and exhibit clustering characteristics. Mukhopadhyay and Dasgupta39 attributed this cluster of earthquakes to the fluid pressure generated due to shearing and infiltration of surface water within dilated seismogenic faults. This intriguing insight draws our attention to other types of natural hazards. High-frequency small earthquakes may have significant impacts on the rock materials on slopes76 along the Jiali Fault, potentially leading to the formation of an earthquake–landslide–river blocking disaster chain. This is a more threatening and frequent disaster. For example, the No. 1 debris flow fan depicted in Fig. 3a was formed by the Guxiang debris flow. In 1953, a massive debris flow event occurred in Guxiang Gully, where approximately 1.1 ×107 m3 of landslide material blocked the Parlung River, causing the water level of the barrier lake to rise by approximately 40 m50. Additionally, large-scale debris flows took place in Guxiang Gully again in 1963 and 197347. In addition to the influence of glaciers, some studies suggest that earthquakes play a significant role in the formation of debris flows by weakening rock and soil structures and creating loose debris configurations48,77. Similar hazards occur frequently along the Jiali fault, causing serious casualties. For example, the Yigong landslide in 2000 blocked the Yigong River from forming a 200-metre-high dam and caused a fairly high-energy flood78, and from 2007 to 2018, four large-scale debris flow events occurred in Tianmo Gully79. The occurrence of such mutual earthquake‒geological disaster feedback events generally manifests in three stages: (1) earthquakes weaken the mechanical properties of slope rock masses, leading to landslides, collapses, or debris flows80,81,82; (2) landslide masses block rivers, forming landslide-dammed lakes; and (3) the elevated water level of landslide-dammed lakes changes seepage pressures and may even trigger additional small-scale earthquakes39. Multiple barrier lakes, such as the Yigong, Guxiang, and Ranwu barrier lakes, are distributed along the Jiali Fault. The impact of water level changes on small earthquakes remains unclear, as does the stability of nearby slope rock and soil masses in response to small earthquakes. Therefore, the risk arising from the mutual feedback of earthquakes and geological hazards along the Jiali Fault necessitates extensive research efforts.

In this study, the Holocene activity of the Jiali Fault in southeastern Tibetan Plateau was investigated. Quaternary sediments developed in Guxian city because debris flows blocked the Parlung River, which provided favourable geological conditions for verifying the Holocene activity of the Jiali Fault. Remote sensing interpretation and field surveys have revealed evidence of secondary faulting of the Jiali Fault disrupting Holocene strata in the Zataduo debris flow fan. The NW–SE-trending fault traverses silty and fine sand rhythmites, as well as debris flow deposits, and is subsequently overlain by later-deposited silty sand layers. The different thicknesses of sediments on both sides of the fault plane clearly indicate right-lateral strike-slip motion. The 14C dating results indicate that the event occurred within 3494 to 2865 cal B.P. In this study, data on the activity of the Jiali Fault is compiled from existing research and reveals that the activity varies in different segments of the fault. Specifically, the middle segment of the Jiali Fault has been more active than the other segments during the Holocene.

The evidence that the Jiali Fault cuts through Holocene strata provides new insights for assessing seismic risk in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau. However, because rapid erosion has led to a scarcity of Quaternary sediments in the Parlung River Basin, the current data are insufficient to establish the slip rate and the major period of earthquakes in southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Therefore, more geophysical, GPS, and trenching data are needed. Further work is being undertaken to address these issues.

Methods

Geological background

The collision of the Indian Plate and the Eurasian Plate has led to the rapid uplift of the Tibetan Plateau25. The continuous northwards convergence of the Indian Plate is controlled by strike-slip faults at both ends of the collision zone8. Particularly in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau, the Himalayan collision zone has undergone significant deflection around the EHS, accompanied by sharp changes in tectonics, geomorphology, and river systems. The EHS plays a crucial role in connecting the Eurasian Plate, the Indian Plate, and the Burmese Plate12. As collision‒compression tectonics transition to strike-slip tectonics, a series of active faults with varying strike-slip rates, sizes, and mechanical properties control crustal deformation and the distribution of major earthquakes in southeastern Tibetan Plateau21,25,83. Similarly, strike-slip shear zones and faults converging near the EHS have segmented the southeastern Tibetan Plateau into structural units, such as the Namche Barwa massif, the Lhasa Block, and the Qiangtang Block10,84. The left-lateral strike-slip Dongju–Milin shear zone and the right-lateral strike-slip Aniqiao–Medog shear zone form the boundaries between the Namche Barwa massif and the Lhasa Block62. The dextral strike-slip Jiali shear zone separates the Qiangtang Block from the Lhasa Block10,26,85. The transitions in the strikes of its branch faults, the Parlung Fault and the Puqu Fault, mark clockwise rotation east of the EHS27,86. Similarly, the deformation of the Gaoligong shear zone, the Ailao Shan–Red River shear zone, and the Sagaing Fault further complicates the movement and deformation patterns in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau13. These fault systems have made southeastern Tibetan Plateau one of the most active regions in terms of global tectonic movements75. The Jiali Fault, on the other hand, is located at the boundary between the continuously compressing Indian Plate and the relatively stable Eurasian Plate and is the most active tectonic boundary north of the EHS.

The Jiali Fault is a large strike-slip fault that separates the Lhasa terrane and is located in front of the collision in the southeastern Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 1a). The Jiali Fault is at the eastern boundary of the Himalayan orogenic belt, which reflects the material flow under Tibetan Plateau and restricts block escape and stress field transformation of the plateau27,87,88. It is considered to play an important role in adapting to the crustal deformation of the Tibetan Plateau25. The total length of the Jiali Fault striking NW–SE (Fig. 1b) is approximately 600 km, and the width of this fault zone is approximately 3–7 km33. The Jiali Fault can be divided into three segments, according to differences in the spatial distribution and GPS data19,33 (Fig. 1b). The western segment stretches from Kemaniya southeast of Naqu to the Jiali District. The sense of movement in this segment is mainly dextral compression, with a strike-slip rate of 5.7 mm/a and a compression rate of 4.6 mm/a. From Jiali to Bomi Districts, the middle segment of the Jiali Fault experiences dextral strike-slip movement, with a strike-slip rate of 1.3 mm/a and a compression rate of 2.9 mm/a. The southeast segment passes along the Yigong and Parlung Rivers and extends from Bomi to Chayu Districts. Near Bomi County, the Jiali Fault is divided into two branches, i.e., the Parlung Fault in the north and the Puqu Fault in the south, and the Poqu Fault likely merges with the Sagaing Fault89.

Remote sensing interpretation and geomorphologic survey

In this study, seismotectonic maps of China and adjacent regions43, the geological structural database of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau44 and the China Active Faults Database (CAFD)90 were utilized as fundamental data for analysing the geometric characteristics and traces of the Jiali Fault. High-resolution satellite imagery (Google Earth) and a digital elevation model (DEM) with a 30 m resolution were employed to estimate the trace of the Jiali Fault on the basis of linear structural patterns and anomalous geomorphic features. Field verification of fault geomorphology was conducted on the basis of the results of remote sensing interpretation and geological data analysis. The survey followed the trend of the Jiali Fault, which extends from Zhongyu city to Ranwu city and has a total length of approximately 286 km (Fig. 1b). Building upon comprehensive analysis of geological data, remote sensing interpretation, and the results of previous studies, the trace of the Jiali Fault was jointly identified (Fig. 2) through field surveys that noted geomorphic indicators, such as fault scarps, fault trenches, outcrops, and linear fault valleys. A secondary field verification was subsequently carried out on the debris flow fans and river terraces intersected by the fault trace. The aim of the second field survey was to search for evidence of the Jiali Fault or its secondary faults traversing Holocene strata. An outcrop was discovered on a debris flow fan near Guxiang, and this outcrop clearly displayed a secondary fault of the Jiali Fault crossing Holocene strata (Fig. 3). The slopes of the outcrop were systematically cleared to reveal clear evidence of the rupture event, which was then photographed and digitally processed on a computer. Additionally, samples from different sedimentary units were collected to determine the ages of the sediments related to the fault.

14C dating method

The materials exposed in the outcrop of the Jiali Fault in this study are river sediments and debris flow sediments, which are good targets for 14C dating. 14C dating has been widely adopted in palaeoseismic studies because of its small error margin and high precision. From the outcrop of the Jiali Fault, sediment samples from various units were collected for 14C dating. The pretreatment, preparation, and testing of the carbon-14 dating samples were conducted at the Beta Analytical Testing Laboratory in the United States via the accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) technique. The AMS measurement was performed on graphite generated through hydrogen reduction of the CO2 sample over a cobalt catalyst. The detailed testing procedures can be found in the standard beta testing process91. The obtained data were calibrated to calendar years via dendrochronological correction. In the application of the calibration curve, the latest IntCal20 curve was used for all the samples92, with OxCal v4.4.

Particle size measurement of the sediment

To accurately identify the relationships between different sand layers at the rupture site, thereby determining the direction of fault movement, we employed a Bettersizer 2600 to measure the particle sizes of the sand layers via the wet method. This instrument supports materials with particle sizes ranging from 0.02 μm to 2600 μm, utilizing a new patented technology that combines Fourier and inverse Fourier optical systems to precisely measure both large and small particles across the widest range. The particle size distribution characteristics of the sand were obtained by receiving and measuring the distribution of energy from the scattered light.

Responses