Spin-orbit entangled moments and magnetic exchange interactions in cobalt-based honeycomb magnets BaCo2(XO4)2 (X = P, As, Sb)

Introduction

The study of Kitaev spin liquid (KSL)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 has recently captured much attention because of its potential use in fault-tolerant topological quantum computation9,10,11. For material realization, early studies suggested 4d– and 5d-transition metal compounds with strong spin-orbit coupling as potential candidates12,13,14,15,16,17. However, subsequent studies showed that these materials host long-range magnetic order at low temperatures due to the appreciable presence of other interactions such as third-nearest-neighbor Heisenberg and non-cubic distortion18. While the search for more ideal candidates for KSL was ongoing, two recent theoretical works concomitantly proposed that cobalt-based compounds with the high-spin d7 configuration can host the formation of pseudospin-1/2 magnetic moments, which is an essential component for the realization of the Kitaev exchange interactions19,20.

Among the materials candidates, BaCo2(AsO4)2 (BCAO)21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32 and BaCo2(PO4)2 (BCPO)33,34,35,36 have attracted much attention recently. It has been reported that exerting magnetic fields in the honeycomb plane can induce two successive magnetic transitions in BCAO and BCPO at low temperatures, analogous to the well-known behavior observed22,23,24,25,35,36 in 4d-based α-RuCl3, where the external magnetic field is considered to suppress the long-range order and to reveal the underlying KSL phase37,38,39. On the other hand, ab initio and model Hamiltonian studies suggest that the strength of the Kitaev interactions in BCPO and BCAO is weak due to the dominant direct overlap integrals between nearest-neighboring cobalt d-orbitals, and that nearest-neighbor and third-nearest-neighbor Heisenberg exchange interactions are the most dominant contributions in these systems27,28,29,30,31.

Inspired by recent experimental and theoretical developments on BCPO and BCAO, here we investigate a whole series of three cobaltate compounds with the chemical formula ({{rm{BaCo}}}_{2}{(X{{rm{O}}}_{4})}_{2},({rm{BC}}X{rm{O}})) (X = P, As, Sb), in which BCSO has not been synthesized yet. The major motivation of the pnictogen substitution is the following: as we replace X with P, As, and Sb, the in-plane lattice constants of BCXO should systematically increase, which affect the direct d–d overlap integrals of Co and, ultimately suppress the strength of nearest-neighbor Heisenberg exchange interactions. On the other hand, the pnictogen substitution can tune the size of the trigonal distortion of CoO6 octahedra. The smaller trigonal distortion is always good for KSL since atomic spin-orbit coupling strength of Co is already small compared to 4d and 5d transition metals. Therefore, the presence of sizable trigonal distortion could lead to the quenching of Leff = 1 orbital degree of freedom, detrimental for realization of the spin-orbital-entangled magnetic moments and spin liquid phases.

For the study on the nature of magnetic local moments and exchange interactions of BCXO series, in this work, we employ first-principles density functional plus dynamical mean-field theory (DFT+DMFT) and Wannierization techniques in combination with recently developed perturbative expressions of the exchange interactions for d7 cobaltates40. Our DFT+DMFT calculations confirm the formation of unquenched Leff = 1 with S = 3/2 spins at Co2+ ions in all three compounds, which forms the Jeff = 1/2 in the presence of spin-orbit coupling. From the comparison of trigonal crystal field-splitting, we find that the size of trigonal crystal fields within the t2g orbital gradually reduces and eventually changes sign as the pnictogen element becomes heavier (P → As → Sb), showing that pnictogen substitution can be a way to tune the crystal fields in this system. Furthermore, the estimation of magnetic exchange interactions based on our first-principles calculations reveals that i) the suppression of the d–d direct overlap between the neighboring Co ions leads to weaker Heisenberg interactions and ii) the sign change of the Kitaev interaction from the antiferromagnetic to ferromagnetic in the nearest-neighbor bondings as we approach from the X = P to Sb limits. In addition, the ratio between the nearest and third-nearest Heisenberg interactions can be also chemically tuned, which can be utilized for the achievement of the geometric frustration via the competition between the nearest- and third-nearest-neighbor Heisenberg interactions in this system30,41,42. Overall, our result shows that the BCXO family is an interesting system with chemically tunable exchange interactions, where geometric and Kitaev-type exchange frustrations can coexist to realize novel magnetism.

Results

Electronic structure from nonmagnetic DFT

The crystal structures of BCAO and BCPO compounds possess rhombohedral geometry with the (Rbar{3}) space group symmetry33,43. We assume that BCSO, which is a fictitious compound with no experimental report yet, has the same (Rbar{3}) structure as BCPO and BCAO. Optimizations of structural parameters show that the substitution of the pnictogen element from P to Sb leads to the enhancement of the in-plane lattice parameters (see Table 1) and the distance between nearest-neighboring Co sites. On the other hand, systematic enhancement of the XO4 tetrahedral volume as a function of the pnictogen substitution (from P to As to Sb) results in contraction of CoO6 octahedral volume, which should directly impact both intra- and inter-site hoppings. Note that such tendencies mentioned above can be checked in the experimental structures of BCPO and BCAO as well, despite the lattice parameters and Co-O bond lengths being slightly underestimated in our calculation results (see Table 1).

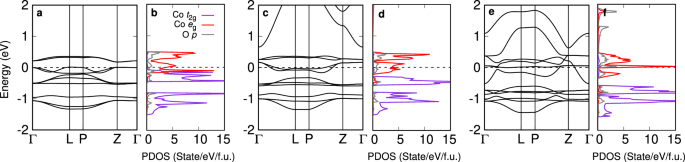

Figure 1 plots nonmagnetic band structures and projected densities of states (PDOS) for BCPO, BCAO, and BCSO without including on-site Coulomb repulsion and spin-orbit coupling. The lower-lying six fully occupied bands are derived from Co-t2g orbitals while partially occupied Co-eg bands are located around EF ± 0.3 eV. Inspecting the almost flat out-of-plane band dispersion of the Co t2g– and eg-bands along Z − Γ, we find that all BCXO compounds host almost perfect two-dimensional nature. Note that in BCSO, the presence of Sb s-orbital degree of freedom introduces dispersive bands along the Z − Γ direction at the Fermi level (see Fig. 1e), which is pushed above the Fermi level as the Coulomb repulsion is introduced (see below). The PDOS clearly shows crystal field-splitting between the t2g and eg states.

Non-spin polarized band structure alongside PDOS (Co-t2g (violet), –eg (red), and O-p (gray)) obtained from LDA calculations for a, b BCPO, c, d BCAO, and e, f BCSO.

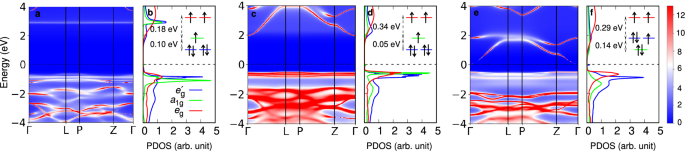

Momentum- and frequency-dependent spectral function alongside momentum integrated projected density of states, plotted for a, b BCPO, c, d BCAO, and e, f BCSO. The results are obtained employing Ising-type Coulomb interactions at 116 K. The insets in the PDOS plots show the crystal field splittings within the Co d-orbitals. Here color bar indicates the intensity of the momentum-dependent spectral function (in arb. unit).

Evidence of formation of L

eff = 1 from DMFT

To gain more insight into the formation of paramagnetic Mott insulating phase, the presence of active Leff = 1 orbital degree of freedom with S = 3/2 spins of Co2+ ions, and for the estimation of the size of trigonal crystal field splitting, we carried out DMFT calculations for BCXO. The accurate crystal structures were obtained by further invoking atomic relaxation within DMFT calculations. We mention here that simple DFT or DFT+U calculations fail to capture paramagnetic Mott insulating features and the presence of unquenched active orbital degrees of freedom in the high-spin d7 configuration28.

Figure 2 shows the LDA+DMFT spectral functions of BCXO. The results are obtained using the Ising-type Coulomb interaction for (U, JH) = (8, 0.8) eV at 116 K. The key feature of the spectra is the formation of a clear Mott gap in all three compounds. From the spectra, it is quite evident that the size of the Mott gap gradually decreases, where dispersive conduction bands with strong pnictogen character move closer to the Fermi level as we go from P to Sb. Panels of Fig. 2b, d, and f show PDOS of BCPO, BCAO, and BCSO, respectively. Crystal field levels of the a1g, ({e}_{{rm{g}}}^{{prime} }), and eg orbitals can be obtained as self-energies in the infinite frequency limit from the quantum Monte Carlo impurity solver, which are depicted in the insets in each of the PDOS panels. We find that i) the size of the t2g–eg splitting is increased as we go from X = P to Sb, consistently with the concomitant volume contraction of the CoO6 octahedron. ii) The size of trigonal crystal field decreases and eventually reverses sign as the pnictogen element changes from P to Sb. The splitting between the a1g and ({e}_{{rm{g}}}^{{prime} }) becomes smallest at X = As, which may be suppressed to zero when a small amount of Sb replacement of As in BCAO is introduced. Importantly, in all three compounds, the size of trigonal splitting is smaller than or at largest comparable to the size of spin-orbit coupling within the Co d-orbitals.

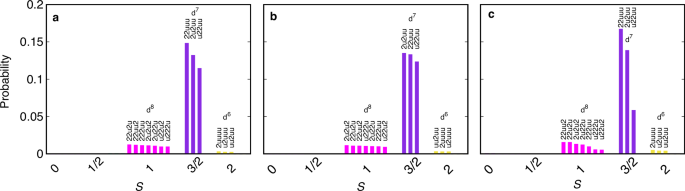

The Monte Carlo probability of atomic multiplets within the Co d-orbitals for all three BCXO compounds are shown in Fig. 3. Here we are focusing on paramagnetic states. So we show probabilities of one spin component only (probabilities of their Kramers partners are the same because of the time-reversal symmetry). Firstly, the DMFT results show that Co d-orbitals are mostly in the d7 high-spin (S = 3/2) sector, confirming the strong suppression of charge fluctuations and the presence of the Mott-insulating character across the whole BCXO series. Secondly, the presence of three major S = 3/2 d7 multiplet states can be seen, confirming the presence of the unquenched Leff = 1 orbital degree of freedom in all three compounds despite the presence of finite trigonal crystal fields. Hence, the inclusion of the atomic spin-orbit coupling should give rise to the formation of the Jeff = 1/2 doublet states in all three BCXO compounds, as suggested in BCAO previously28. Furthermore, comparing Leff = 1 states for BCXO, we find that the Leff = 1 multiplet states in BCPO and BCAO are more equally populated than in BCSO. This can be attributed to the larger size of the trigonal crystal field in BCSO than those in other two compounds (compare insets of Fig. 2b, d, and f).

a–c Probability of atomic multiplet states plotted for BCPO, BCAO, and BCSO, respectively with different spin configurations showing the formation of active Leff = 1 orbital degree of freedom. Here probabilities are depicted for one spin component because of time-reversal symmetry and only those states are shown which have probabilities greater than 10−3. In the atomic configurations u and 2 represent singly occupied state with spin-up electron and a doubly occupied state with both spin-up and spin-down electrons.

Hopping integrals and magnetic exchange interactions

As the presence of the unquenched Leff = 1 effective orbital degree of freedom which results in the formation of Jeff = 1/2 pseudospin in BCXO is checked, the following steps are adopted to estimate magnetic exchange interactions. First, hopping integrals between d–d and p–d hopping processes were computed from ab initio calculations. Then, we employed a recently developed strong-coupling perturbative expression for magnetic exchange interactions for d7 cobaltates40. Notably, this spin model has been shown to successfully explain the origin of weak Kitaev and dominant Heisenberg exchange interactions in BCAO, and may be applied for other types of honeycomb cobaltates as well44. We note in passing that because of decreasing gap size with pnictogen substitutions from P to Sb, which is analogous to the gap reduction in the α-RuX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) compounds45, screening should become stronger which may result in the strength of the Coulomb repulsion on d and p orbitals that appear in the perturbative expressions of the exchange interactions40. This might give rise to the overall enhancement of the exchange interactions in the insulating regime in the Sb-limit. In this study, we fixed the value of Coulomb parameters on d and p orbitals as per reference40 to focus on the evolution of the exchange interactions as a function of the pnictogen substitution. For ideal edge-sharing octahedra on a honeycomb lattice with three-fold symmetric first and third nearest-neighbor interactions, the Hamiltonian of the spin model can be written as

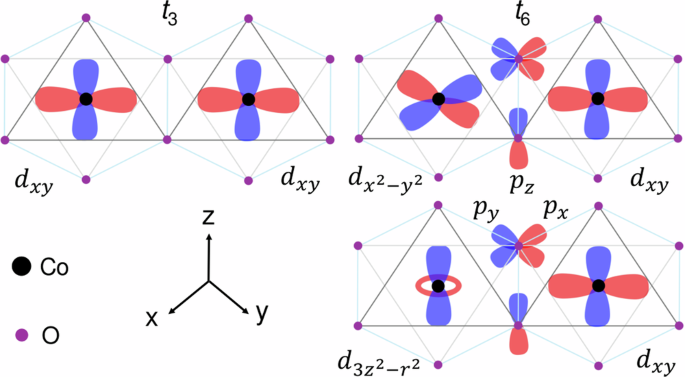

Here, α, β, γ ∈ {x, y, z} simultaneously represent the local octahedral coordinates for the directions of the spin S = 3/2 and Leff = 1 momenta and the corresponding bond directions. The J1 (J3), K1 (K3), and Γ1 (Γ3) stand for first- (third-) nearest-neighbor Heisenberg, Kitaev, and off-diagonal exchange terms, respectively. It must be noted that second-nearest-neighbor interactions are present in cobaltates, but they are much smaller in magnitude than first and third neighbors22. Table 2 summarizes the six major hopping parameters for d–d (ti (i = 1…, 6)) and two p–d (tpdσ, tpdπ) processes for a nearest-neighbor Co-Co bonding. Following the nearest-neighbor bond and local octahedral coordinate as depicted in Fig. 4, among the six hopping parameters t1, t3, t4, t5 denote intraorbital direct hopping between dxz/yz, dxy, ({d}_{{{rm{3z}}}^{2}-{{rm{r}}}^{2}}), and ({d}_{{{rm{x}}}^{2}-{{rm{y}}}^{2}}), respectively. The t2 and t6 denote hopping from dxz–dyz and t2g–eg mediated by O p orbitals, which include both direct and indirect hoppings. Note that applying the threefold rotation operation generates the other two nearest-neighbor hopping integrals.

Schematic diagram of two major hopping channels, depicting d–d and p–d hopping processes in BCXO compounds.

Analyzing d–d and p–d hopping processes for BCXO, we make several important observations. Since the in-plane lattice constants increase with the substitution of heavier pnictogen elements at X sites (see Table 1), Co-Co distance is enhanced which affects direct d–d overlap integrals. From Table 2, we identify two major hopping channels, namely t3 and t6 as schematically depicted in Fig. 4 that play a crucial role to suppress nearest neighbor Heisenberg exchange. As evident from Table 2, t3 monotonically decreases while t6 increases simultaneously as a function of pnictogen substitutions. The reduction in t3 hopping integral is attributed to enhancement in Co-Co distance due to the increase in-plane lattice constants with pnictogen substitutions. On the other hand, the enhancement of t6 hopping parameter is ascribed to a reduction in Co-O bond distance because of an increase in Co-O-Co bond angle from P → Sb (see Table 1). For the third neighbor, direct hopping strength ({t}_{5}^{{prime} }) is the largest one, which plays an important role to dictate third nearest-neighbor antiferromagnetic Heisenberg exchange.

Next we compute magnetic exchange interactions using hopping parameters from Table 2. The results are listed in Table 3 for the first- and third-nearest-neighbors. There are a total of three exchange paths denoted by A (t2g–t2g), B (t2g–eg), and C (eg–eg), respectively. Each exchange process involves three distinct mechanisms, numbered 1 (direct), 2 (double-hole), and 3 (cyclic) exchange processes, resulting total of nine contributions to exchange as described in previous studies19,40. The direct exchange involves virtual excitations due to inter-site charge fluctuations between two neighboring Co sites (({d}_{i}^{7}{d}_{j}^{7}to {d}_{i}^{6}{d}_{j}^{8})). The double-hole process is virtual charge-transfer excitations between two Co d orbitals mediated by an O p (({d}_{i}^{7}{p}^{6}{d}_{j}^{7}-{d}_{i}^{8}{p}^{4}{d}_{j}^{8})), when double-hole are created on the oxygen p-orbitals. Lastly cyclic exchange is a quantum mechanical process in which total two holes are created during an intermediate process at two O p orbitals between two neighboring Co sites (({d}_{i}^{7}{p}_{1}^{6}{p}_{2}^{6}{d}_{j}^{7}to {d}_{i}^{8}{p}_{1}^{5}{p}_{2}^{5}{d}_{j}^{8})). For the nearest-neighbor exchange, all nine different contributions are listed in Table 3. Only three direct exchange contributions are tabulated for the third-nearest-neighbor terms due to the complexity of enumerating all possible p–d virtual processes.

Comparing Heisenberg, Kitaev, and off-diagonal exchanges in Table 3 for the nearest-neighbor part, we find that the ferromagnetic Heisenberg exchange is the most dominant in all BCXO. As the pnictogen element changes from P to Sb, the strength of J1 monotonically decreases. Concurrently, antiferromagnetic Kitaev exchange gradually decreases and eventually flips the sign to become ferromagnetic. The values of our estimated exchange interactions for BCAO are consistent with those reported previously, which predicted dominant Heisenberg and weak Kitaev exchange terms40. Furthermore, to unravel how Heisenberg and Kitaev exchange change with pnictogen substitutions, we analyze the contribution of each exchange process to total exchange. Table 3 reveals that A1, B2, and B3 are the three dominant contributions from three different exchange paths in BCXO. Because of the opposite sign of B2 and B3, a large part of exchange interactions from t2g–eg and eg–eg paths cancel each other so that total Heisenberg and Kitaev exchange interactions mostly arise from the t2g–t2g path.

In addition, we find that the largest contribution to nearest-neighbor Heisenberg exchange stems from t3 hopping in BCXO, whose strength gradually reduces from P to Sb. On the other hand, the direct exchange process originating from t1t3 hopping results in largest contribution to nearest-neighbor antiferromagnetic Kitaev exchange for P and As. With the substitution of Sb, t6-derived direct exchange term now dominates over t1t3 mediated exchange, resulting in the sign reversal of the Kitaev exchange.

Since many cobaltate compounds show significant third-nearest-neighbor exchanges that play a crucial role in geometrical frustration, and also in stabilizing experimentally observed double zigzag magnetic order22, we compute those from the third-neighbor hopping terms. The results are shown in Table 3. We comment that due to the overwhelming number of possible oxygen-mediated virtual processes in the third-neighbor exchange interactions, here we only present results from the direct exchange process. We observe finite antiferromagnetic Heisenberg exchange with almost negligible Kitaev interaction. The values of estimated − J3/J1 ratios are 0.26, 0.43, and 0.22 for BCPO, BCAO, and BCSO, respectively. According to the study of the J1–J3 model, there are three plausible ground states for BCXO, namely ferromagnetic for 0< − J3/J1<0.25, spiral phase for 0.25< − J3/J1<0.40, and zigzag magnetic ground state beyond 0.4041,42. Experimentally, − J3/J1 for BCAO has been reported to be 0.26-0.3422,30 which is indicative of geometrical frustration. Our calculated − J3/J1 ratios are reasonably comparable to the reported one.

Discussion

Based on our first-principles calculations and estimations of magnetic exchange interactions, we comment on a few important aspects of this study. To capture paramagnetic Mott phase and formation active Leff = 1 orbital degree of freedom, incorporation of dynamical mean-field correlation is essential in BCXO. Since the substitution of the pnictogen elements systematically increases the lattice constants, it is effective in controlling the Co-Co direct hopping and hence, the strength of direct exchange interaction. Besides, it can result in switching the sign of Kitaev exchange from antiferromagnetic to ferromagnetic and also, tuning the −J3/J1 for the realization of the geometric frustration. In addition to those, the size of trigonal crystal-field splitting within t2g sector in BCXO can be tuned via the pnictogen substitution. We predict that, despite the absence of the X = Sb limit of the BCXO system, a gradual Sb replacement of As in BCAO via chemical doping can be an interesting way to tune exchange interactions. This may lead to an interesting coexistence of geometric frustration induced by the J3–J1 competition and sizable Kitaev interaction, which might result in a novel phase of matter. Furthermore, based on the recent literature report on BaCo2(AsO4)2−2x(VO4)2x46 we comment that a similar role of Sb substitution in BCXO can be achieved via partial substitutions of As with V. With a low concentration of V substitutions in this compound, suppression of long-range magnetic order has been reported, which is consistent with our understanding on Sb substitution. Additionally, here we mention a similar observation in another layered honeycomb cobaltate Cu3Co2SbO6, where applying epitaxial strain suppresses magnetism due to enhanced frustration44, similar to the case of BaCo2(AsO4)2−2x(VO4)2x46.

In summary, our electronic structure calculations of BCXO reveal the formation of the paramagnetic Mott phase in all three compounds. Our study reveals the existence of the unquenched effective orbital degree of freedom Leff = 1 and S = 3/2 at Co2+ ions with a sizable trigonal crystal field, which is comparable to the size of atomic spin-orbit coupling of Co. Therefore, with spin-orbit coupling many-body Jeff = 1/2 Kramer’s doublet is expected to form in BCXO. The analysis of magnetic exchange interactions reveals that in all three compounds, nearest-neighbor Heisenberg exchange is the dominant interaction with finite Kitaev exchange. Finally it is shown that the pnictogen substitution can be a useful tool to tune the exchange interactions and frustrations in the BCXO series, highlighting the potential of these compounds in studying novel quantum magnetism.

Methods

Density functional theory calculations

DFT calculations were carried out using pseudopotential-based Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (vasp) within projector augmented wave (PAW) formalism47. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) generalized gradient approximation (GGA) adapted for solids48 was chosen as the exchange-correlation functional. Additionally, effective on-site Coulomb potential (Ueff = 2, 4 eV) was applied to the d orbitals of Co using a rotationally-invariant DFT+Ueff formalism49. The planewave cutoff and size of k-grids were set to 500 eV and 14 × 14 × 14, respectively. The structural optimization was performed using PBEsol+U to get a better agreement of Co-O bond lengths and lattice constants with the experiment. For optimization of crystal structures, force and energy tolerance factors were fixed to be 10−4 meV/Å and 10−9 eV respectively. It is worth noting that optimizing the crystal structure without the consideration of the on-site Coulomb repulsion and magnetism greatly underestimates Co-O bond length, resulting in spurious metallic behavior in the dynamical mean-field calculations28. Furthermore, to estimate hopping parameters between different Co d orbitals, we employed the maximally-localized Wannier function (MLWF) method50 as implemented in wannier9051 package. Note that the Wannier functions were obtained from DFT calculation without including the Ueff and magnetism to avoid double-counting effects of the Coulomb repulsion and exchange splitting.

Dynamical mean-field theory calculations

First-principles DFT+DMFT calculations were performed within the framework of the local density approximation (LDA) of the Cerpeley-Alder parametrization52, employing the Embedded DMFT Functional (edmftf) code53,54, interfaced with the full-potential wien2k55 code. The primitive Brillouin zone of BCXO was sampled with a 14 × 14 × 14 k-grid mesh. The (R{K}_{max }) was set to 7.0. The calculation results were obtained using an Ising-type density-density Coulomb interaction and were further verified using the rotationally-invariant full Coulomb interaction. The temperature of the bath was set to be 116 K. The on-site Coulomb repulsion and Hund’s coupling parameters were chosen to be (U, JH)=(8, 0.8) eV. All calculation results presented below employed a nominal double-counting scheme53. Furthermore, DMFT calculation results were tested with different choice of nominal occupancies in nominal double counting scheme and main result is justified by comparing with exact double counting scheme56 (see Supplementary Note 3). We emphasize that our DMFT results remain qualitatively the same within a range of the values of (U, JH) parameters and choices of nominal occupancies28. The single-site quantum impurity problem was solved self-consistently using a hybridization-expansion continuous-time quantum Monte Carlo method, where the Co d orbitals were chosen as the correlated subspace and the number of the total Monte Carlo steps was chosen to be 24 × 108. To achieve better accuracy in crystal structures of BCXO, DFT+Ueff-optimized structures were further subject to the structural relaxation within DMFT calculations until the largest Hellmann-Feynman force on each atom reaches below 3 meV/Å.

Responses