Spin pumping effect in non-Fermi liquid metals

Introduction

Dimensionality plays a vital role in many-body physics, particularly, the universal critical phenomena near a quantum critical point (QCP)1. Two-dimensional (2D) correlated systems with strong quantum fluctuation have been a fertile land for various unconventional quantum phases of matter and associated QCPs, including the cuprate oxide layers in high-Tc superconductors2,3, non-Fermi liquid metals4 and exotic quantum magnets5. The atomic-level 2D nature facilitates the formation of the proximity effect, thus, offering a practical platform for co-integrating distinct physical ingredients by artificial design of heterostructures6. The stacking and twisting of 2D materials have expanded the boundary of condensed matter physics and give birth to the van der Waals (vdW) heterostructure5 and “twistronics”7. The lower dimensionality enables otherwise unattainable fabrication, manipulation, and measurement as their bulk counterparts8. The strain9, gating10, light11 and electric field10 can couple with various internal degrees of freedom — charge, spin, orbit, lattice, etc. This offers unprecedent tunability towards QCPs. In the mediated quantum critical region, wild quantum fluctuations can lead to Fermi liquid instability for the conduction electrons12. The breakdown of coherent Fermi-liquid quasiparticles13 is the most dramatic manifestation of the many-body correlation, which is known as non-Fermi liquid (NFL) behavior.

Despite the success in fabricating 2D magnetic thin layers, the experimental detection of the critical spin fluctuation poses significant challenges. The conventional magnetic probes, such as neutron scattering, superconducting quantum interference device magnetometry, are designed for bulk magnets, therefore, are insensitive provided the weak signals from magnetic vdW materials. The effectiveness and efficiency of optical probes, such as Raman spectroscopy or magneto-circular dichroism, are currently under investigation14. It is greatly desired that a clever implementation of the magnetic vdW heterostructure probes the many-body correlation in directly in the spin channel. Many-body correlations have been probed using the pure spin current in the spintronics community15. The interface at the heterostructure of various 2D magnetic materials is particularly beneficial for harnessing spintronic functionalities16. The spin current can be mediated by various quasiparticles given the rich combination of heterstructures.

The spin pumping effect17,18, originally designed at the interface of magnetic heterostructure to generate pure spin current, develops potential as a sensitive probe in measuring the magnetic phase transitions in 2D thin layers19. The heterostructure comprises a magnetic insulator subjected to dynamical driven field and a 2D quantum magnet as the spin current receiver. Conventionally, one consider a ferromagnetic insulator (FI) with a precessional magnetization at its resonance states, the spin current is injected into the adjacent material via interfacial spin exchange interaction20,21,22. The spin injection has a backaction on the FI in modulating the frequency of feromagnetic resonance (FMR) and the Gilbert damping. The modulated FMR signal carries information about the dynamical spin susceptibility of the 2D magnetic thin layer, making it a effective probe for studying its spin characteristics of 2D magnetic materials. It is therefore appealing to probe the spin correlation, particularly the critical spin fluctuation near the QCP, in 2D magnetic heterostructure using the spin pumping.

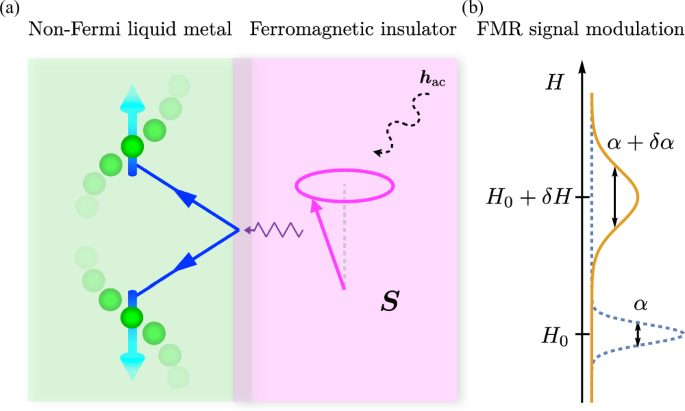

In this work, we consider the spin pumping effect in the magnetic heterostructure composed of a 2D NFL metal and a ferromagnetic insulator (FI) thin film schematically plotted in Fig. 1. We demonstrate that the spin pumping is an effective method to probe the critical spin fluctuation for 2D magnetic heterostructure in the dynamic regime near the QCP. We consider the type of QCP near a Pomeranchuk instability which is described by gapless Fermi surface coupled with critical bosons. We begin with generic analysis based on universal scaling rule near the QCP; Then, we take the 2D Ising nematic QCP induced NFL as a concrete example which is relevant to underdoped cuprates3 and Fe-based superconductors23. The FI is at the resonant frequency under the microwave radiation, the magnon excitations are damped by the phenomenlogical Gilbert mechanism. Pure spin current is injected into the adjacent NFL where the spin angular momentum is carried by “non-quasiparticles”. The backaction of the spin injection can be read off from the magnon self-energy correction. The perturbation is carried out up to second order in interfacial exchange coupling in the Keldysh representation which gives rise to a direct relation between the magnon self-energy and the dynamical spin susceptibility in the NFL metal.

a Schematic plot of the NFL/FI bilayer structure for the FMR-driven spin pumping experiment. The pink arrow in the FI indicates the spin S precessing in the external ac magnetic field hac. The blue arrows in the NFL metal indicate the itinerant electrons exchanging spin angular momentum at the interface with magnons in the FI layer. The gradually fainted green balls illustrate the incoherent quasiparticles in the NFL metal. b The FMR signal modulation due to the interlayer coupling, where H is the magnitude of the Zeeman field and α is the coefficient of the Gilbert damping.

We evaluate the dynamical spin susceptibility χuni(ω) near Ising nematic QCP when the itinerant spins in NFL metal are subjected to the interfacial exchange interaction from the FI. The interfacial spin exchange interaction not only facilitates the spin injection and FMR modulations but also provides a relaxation channel for the itinerant spins. Thus, it promotes the spin dynamics in the uniform component which conceives the non-quasiparticle nature of the underlying NFL metal. To this end, we deal with the fermion-boson coupling near the QCP in a self-consistent manner, and then we obtain power-law scalings for χuni(ω) perturbatively in terms of interfacial exchange interaction. The FMR signals, namely the shift of resonance frequency and enhanced Gilbert damping coefficient, are significantly modulated: The enhanced Gilbert damping coefficient exhibits a power-law divergence in the low-energy limit indicating that the conventional Gilbert mechanism becomes invalid. The scaling exponents are intimately related to the university class of the underlying QCP. At finite temperatures, we adopt revised Eliashberg equations for fermions and bosons where bosonic correlation length and electron scattering rate acquire characteristic temperature dependence. In the quantum critical regime, the Gilbert damping is restored and the temperature dependence in the enhanced Gilbert damping coefficient captures the distance towards the QCP. We show out that, at both zero and finite temperatures, the shift of resonance frequency captures characteristics of quasi-particle disappearance.

Results

Magnetic heterostructure

Let’s consider the magnetic heterostructure composed of a NFL metal and a FI thin film shown in Fig. 1a. The FI is driven by an external ac magnetic field in resonance with the precession of local spins. The spin current is injected into the NFL metal via the spin exchange coupling at the interface. The full Hamiltonian of the NFL/FI heterostructure comprises three parts,

The first term describes the FI with the ferromagnetic Heisenberg model subjected to an oscillating magnetic field,

in which J > 0 is the ferromagnetic exchange coupling constant. Si stands for the local spin at site i in the FI. H is the magnitude of the Zeeman field. γg (< 0) is the gyromagnetic ratio. hac and ω are the amplitude and the frequency of the circularly oscillating external magnetic field, respectively. The second term in Eq. (1) is the exchange coupling at the interface between local spins in the FI and itinerant electrons in the NFL metal,

where ({{boldsymbol{s}}}({{boldsymbol{r}}})=frac{1}{2}{c}_{alpha }^{{dagger} }({{boldsymbol{r}}}){{{boldsymbol{sigma }}}}_{alpha beta }{c}_{beta }({{boldsymbol{r}}})) is the itinerant electron spin operator. The exchange coupling function in the reciprocal space is approximately given by ref. 24

where A is the area of the NFL at the 2D interface, and N is the number of sites in FI. The first and second terms describe averaged uniform and spatially uncorrelated roughness respectively. l is introduced as an atomic scale length for the continuous model. J1 and J2 are the mean value and the variance of the exchange coupling.

The third term in Eq. (1) is a fermion-boson coupled model describing the NFL induced by critical boson modes. The mechanism and classification of different types of NFL has a long and distinguished history4,25,26,27 with ever-increasing new developments28,29,30,31,32. The critical boson induced NFL can be described by a generic form of Hamiltonian,

Here ({c}_{alpha }^{{dagger} })(cα) is the electron creation (annihilation) operator for spin the spin up/down α = ± . ϵ(k) is the spin degenerated, bare electronic dispersion near the Fermi surface. ϕ is a critical fluctuating bosonic field admitting a Ginzburg-Landau expansion near a QCP tuned by r → 0. λ is the coupling constant of electrons and the bosonic order parameter field. O(r) is a fermion bilinear operator, which transforms inversely as ϕ(r) under symmetry actions guaranteeing the invariance of the coupling term. We note that the boson field ϕ(r) is not directly coupled to the FI via magnetic exchange interactions. It’s reasonable to assume that the boson field is either regarded as non-magnetic for the Ising nematic case, or being ineffective in coupling to the local magnetic moment Si in FI. Invoking the direct coupling of both itinerant spins and local moments, e.g., near the magnetic QCPs, would introduce additional complexity, which is left for future studies.

Spin pumping and FMR modulations

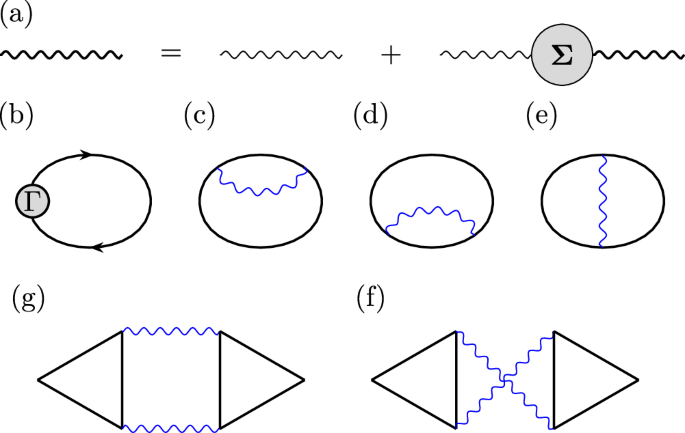

The spin pumping, at a microscopic level, is initiated by the magnetic exchange interaction at the heterostructure interface between the magnetization in the FI and the electron spin of the NFL. This interaction promotes spin injection and generates a self-energy correction for the magnons in the FI as a backaction, modulating the frequency of FMR and Gilbert damping20,21,22. The modulated FMR signal carries information about the dynamical spin susceptibility and is shown to be related to the magnon self-energy. The Dyson equation for the magnon Green function, illustrated in Fig. 2a, is written as

where the bare magnon Green function ({G}_{0}^{-1}) has a dispersion that reads ωk = Dk2 − γgH (γg < 0) and the imaginary term proportional to ω33 is known as Gilbert damping with a coefficient α17. In addition, there emerges a magnon self-energy Π(k, ω) due to the backaction of the spin injection. The FMR modulation shown in Fig. 1b is determined by the uniform component (k = 0) of the magnon Green’s function, in which the pole dictates the resonance condition, (omega +{gamma }_{{{rm{g}}}}H-{{rm{Re}}}{Pi }_{{{boldsymbol{k}}} = 0}(omega )=0), thus the resonance frequency is shifted by (delta H={gamma }_{{{rm{g}}}}^{-1}{{rm{Re}}}{Pi }_{{{boldsymbol{k}}} = 0}(omega )). The imaginary part of the self-energy leads to an enhanced Gilbert damping coefficient, (delta alpha =-{omega }^{-1}{{rm{Im}}}{Pi }_{{{boldsymbol{k}}} = 0}(omega )).

a Dyson equation for the magnon Green’s function. The thin and the thick wavy lines are the bare and the renormalized magnon Green’s functions, respectively. The shaded circle represents the magnon self-energy Π. b The fully renormalized charge polarization bubble. Thick straight lines are the fermion propagators and shaded circle represents the vertex function in the fermion-boson model Eq. (5). c–g Feynman diagrams for the charge polarization bubble. At leading order in interfacial exchange coupling (tilde{J}), there are (c, d) the self-energy diagrams and (e) the vertex diagrams. On the next leading order, the potentially relevant diagrams are (f, g) the Aslamazov-Larkin diagrams.

The magnon self-energy can be calculated perturbatively up to the second order in terms of the external oscillating magnetic field hac and the exchange coupling ∣Jk,q∣ [see Supplementary Note 2 for derivations],

with (chi ({{boldsymbol{q}}},omega )equiv iint,dt{e}^{i(omega +i{0}^{+})t}Theta (t)langle [{s}_{{{boldsymbol{q}}}}^{+}(t),{s}_{-{{boldsymbol{q}}}}^{-}(0)]rangle ) being the retarded spin susceptibility for NFL metals. Inserting the exchange coupling function in Eq. (4), the magnon self-energy is given by ref. 24

where two terms corresponds to uniform and uncorrelated roughness contribution of the interfacial exchange interaction. J1, J2 are the mean value and variance, singling out the uniform and the local components of the dynamical spin susceptibility. They are expressed as χuni(ω) ≡ χ(q = 0, ω) and χloc(ω) ≡ ∑qχ(q, ω).

In the vicinity of the QCP at r = rc, the dynamical spin susceptibility takes the following universal scaling form at (T=0,chi ({{boldsymbol{q}}},omega ,r-{r}_{{{rm{c}}}})={xi }^{{d}_{chi }}chi ({{boldsymbol{q}}}xi ,omega {xi }^{z})), in which ξ is the spatial correlation length, dχ is the scaling dimension of the spin susceptibility, and z is the dynamical exponent. At the QCP, the correlation length diverges, leading to the reduced scaling form, (chi ({{boldsymbol{q}}},omega ,T=0)={omega }^{-{d}_{chi }/z}tilde{chi }({{boldsymbol{q}}}/{omega }^{1/z})). The magnon self-energy correction has different power-law scaling forms inherited from the uniform and local components in respective limits,

Here dχ and z are two independent critical exponents which can be uniquely determined by tuning the interfacial roughness (eta ={J}_{1}sqrt{A}/({J}_{2}l)). And, dχ is often related to the physical dimension d where deviation are encountered when hyperscaling is violated approaching certain QCPs34,35. The power-law scalings are in sharp contrast to the conventional linear-in-frequency Gilbert damping term, thus reflects the NFL behavior associated with the QCP. In the finite temperature regime mediated by the QCP, a different set of critical exponents ({d}_{chi }^{{prime} }) and ({z}^{{prime} }) emerge (chi ({{boldsymbol{q}}},omega ,r-{r}_{{{rm{c}}}},T)={L}_{tau }^{{d}_{chi }^{{prime} }/{z}^{{prime} }}tilde{chi }left({{boldsymbol{q}}}{L}_{tau }^{1/{z}^{{prime} }},omega {L}_{tau },xi (T)/{L}_{tau }^{1/{z}^{{prime} }}right)). Lτ = 1/(kBT) is the characteristic scale in the imaginary time. Note that the correlation length (or the boson mass) is originally a quantum parameter, now, acquires a T-dependence endowed by higher order magnon interactions. The uniform and local components are expressed in terms of correlation length as

Henceforth, we consider the smooth interface η ≫ 1 and the interfacial exchange interaction is reduced to ({{{mathcal{H}}}}_{{{rm{ex}}}}={J}_{1}/sqrt{N}{sum }_{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}{{{boldsymbol{s}}}}_{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}cdot {{{boldsymbol{S}}}}_{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}). Our focus is the uniform component of the spin susceptibility χuni(ω) that dominates the magnon self-energy correction in Eq. (8). However, for a decoupled Fermi liquid/NFL metal layer with a single source of magnetism, χuni(ω) vanishes as a consequence of total spin conservation. In contrast, the scenario illustrated in Fig. 1a is fundamentally different. The magnetic heterostructure constitutes a correlated system with two magnetic degrees of freedom. The interface provides a relaxation channel for itinerant spins enabling the spin dynamics in the NFL metal. Additionally, we note that the local component of the spin susceptibility χloc(ω), at a rough interface is not subject to the strict constraints of spin conservation, which is an interesting topic but beyond the scope of this study.

Non-Fermi liquid at the Ising nematic QCP

The Pomeranchuk instability near the 2D Ising nematic QCP is described by critical bosonic modes of the collectively distorting Fermi surface. The four-fold lattice rotational symmetry of the 2D Fermi surface is on the verge of spontaneously breaking down to two-fold. The order parameter field ϕ(r), in the NFL Hamiltonian in Eq. (5), is coupled to the fermionic bilinear O(r) as

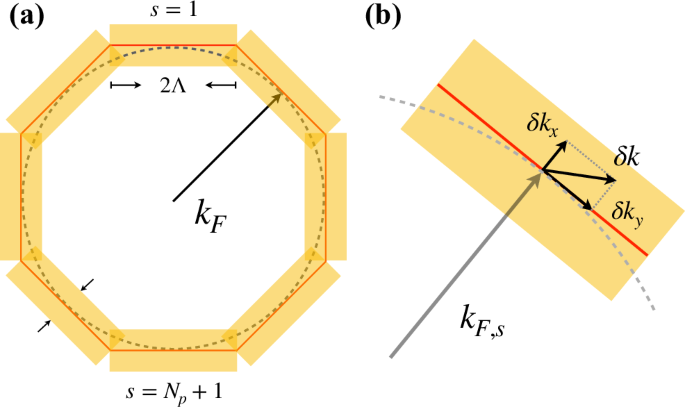

where the d-wave form factor can take a form ({d}_{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}=cos {k}_{x}-cos {k}_{y}). We adopt the patch decomposition scheme4 and divide the Fermi surface into 2Np number of patches labeled by s-index in Fig. 3a. The s’th patch is centered at the Fermi momentum kF,s and the momentum nearby is expanded as k = kF,s + δk in Fig. 3b. The small variation δk can be further decomposed into radial and tangential components δkx, δky with respect to the directional vector (hat{k}={{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}},s}/{k}_{{{rm{F}}},s}). The coupled fermion-boson model specified by Eq. ((5), (11)) admits a self-consistent solution[see Supplementary Note 1 for a self-contained review], where the renormalized fermionic Green function reads ({g}_{s,{{rm{R}}}}(delta {{boldsymbol{k}}},omega )={left(i{c}_{{{rm{F}}}}{d}_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}},s}}^{2}| omega {| }^{a}-{v}_{{{rm{F}}}}delta {k}_{x}-frac{kappa }{2}delta {k}_{y}^{2}right)}^{-1})36 where the spin index α is omitted and the exponent is expressed as (a=frac{d}{z}=frac{2}{3}). The dynamical exponent z = 3 holds up to three-loop perturbations36. The bare dynamic term iω is overwritten by the fermionic self-energy ΣF(kF,s, ω) in the low-energy regime (| omega | < {omega }_{{{rm{c}}}}={c}_{{{rm{F}}}}^{3}). The real part of the self-energy can be derived using the Kramer-Kronig relation in the low-energy regime as ({{rm{Re}}}{Sigma }_{{{rm{F}}}}({{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}},s},omega )=-sqrt{3}{d}_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}},s}}^{2}{c}_{{{rm{F}}}}{{rm{sgn}}}(omega )| omega {| }^{2/3}). The NFL feature with kF,x ≠ ± kF,y manifests as a vanishing quasiparticle weight: ({Z}_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}},s}}(omega )equiv {left[1-{partial }_{omega }{{rm{Re}}}{Sigma }_{{{rm{F}}}}({{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}},s},omega )right]}^{-1}simeq {d}_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}},s}}^{-2}{omega }^{1/3}{to }^{omega to 0}0).

a The critical Fermi circle in 2D is approximated by the orange polygon, the dashed gray circle represents the Fermi surface and each red line segment stands for decoupled patches with the width 2Λ. Orange fainted rectangle is the low-energy region for a single decoupled patch labeled by index s ∈ [1, 2Np]. b The small momentum variation δk in the s‘th patch centered at kF,s is decomposed into radial component δkx and tangential component δky.

The itinerant spins in the NFL are degenerate and are not on the verge of forming any magnetization since the critical fluctuation is in the charge channel. The spin susceptibility is proportional to the charge polarization bubble, plotted in Fig. 2b, is given by ({chi }_{{{rm{uni}}}}(i{q}_{0})=-Amathop{sum }_{s = 1}^{2{N}_{{{rm{p}}}}}{Pi }_{s}(i{q}_{0})). The charge in each patch is separately conserved provided that the inter-patch scattering is ignored. A direct evaluation of polarization bubble at s’th patch Πs(iq0) using the fully renormalized fermionic Green function yields a non-vanishing result [see Supplementary Note 2a]

where we have kept a shortened notation for the small variation denoted as k. However, this naive result contradicts the generic constraint imposed by the spin conservation: χuni(iq0) = 0 for any given frequency. The discrepancy arises from inappropriate and incomplete accounting of the critical boson fluctuations. By using the renormalized Green function, we take into account of the self-energy corrections in Eq. (12); Whereas, the vertex corrections are overlooked, which is crucial in maintaining the Ward-Takahashi identity in the dynamic limit ∣Ω∣ > vFq. In fact, at the QCP, if we adopt the renormalized fermion Green function, the vertex corrections are of order one at any perturbative order in ({{mathcal{O}}}(lambda ))37,38. Summing up infinite ladder series of vertex corrections in Fig. 2b yields the correct result for uniform spin susceptibility at Ising nematic QCP,

We derive the cancellation between self-energy and vertex in Supplementary Note 2 where we extend the derivation to a noncircular 2D Fermi surface.

Furthermore, we turn on the coupling between itinerant spins and local moments at the magnetic heterostructure interface [see Eq. (3)]. The magnetic excitation in the FI is a Goldstone mode of the FM order, which has been proven ineffective in coupling to quasiparticles in the Fermi liquids39. The NFL phase already formed at Ising nematic QCP is not sabotaged. As a result, the primary effect of the magnetic excitations is the promotion of the spin dynamics in the NFL metal. To this end, we use the fully renormalized NFL Green function at Ising nematic QCP, and treat interfacial spin exchange perturbatively. Since the restriction of spin conservation for the NFL metal is lifted, the magnetic heterostructure, originally designed for the spin pumping, represents a natural setup to directly probe the spin dynamics of non-quasiparticles at a Pomeranchuk instability.

Divergent FMR modulation at T = 0

The analysis of the spin dynamics at the magnetic heterostructure interface involves two magnetic degrees of freedom. The evaluation of spin-polarization bubble for the itinerant electrons perturbatively in interfacial spin exchange interaction requires renormalizations from all diagrams depicted in Fig. 2, that includes (a) the self-energy(SE) diagram, (b) the vertex(V) diagram and (c) Aslamazov-Larkin(AL)-type diagrams.

To set the stage, let’s first consider the case for a free-standing 2D layer of itinerant electrons where the magnetism has a single source. The uniform spin susceptibility calculated from SE+V diagrams in Fig. 2c–e is not vanishing, which reads

It is pointed out that40 the seemingly higher order AL diagrams in Fig. 2f, g are crucial in restoring the spin conservation near the magnetic QCPs. The dynamical fermion-fermion interaction is mediated by the critical fluctuations in the spin channel. The Stoner criterion reduces AL diagrams to the same order as self-energy and vertex diagrams which restores the spin conservation with χuni(q0) = ISE(q0) + IV(q0) + IAL(q0) = 0.

In sharp contrast, the spin pumping setup in Fig. 1a is at the magnetic heterostructure interface with two sources of magnetism, namely, the itinerant electron spins in NFL metal and the local moments in FI. It is important to note that the NFL is formed at an Ising nematic QCP in the charge channel. And, the effective interaction between these non-quasiparticles is in the spin channel, which is mediated by the magnon excitations in the adjacent FI. The magnon has its own dynamics due to magnon-magnon interaction as described in Eq. (6), which is fundamentally different from the Landau damping inherited from the gapless fermions. In this case, the AL diagrams is officially a higher order perturbation compared with SE+V diagrams. As a result, the overall dynamic spin susceptibility at leading order, as given in Eq. (14), is non-vanishing, consistent with the expected breaking of spin conservation for the NFL metal.

To be concrete, we adopt the zero-temperature NFL Green function and calculate the uniform spin susceptibility by evaluating the SE and V diagrams in Fig. 2c, d and Fig. 2e, respectively. They are given by

where ∫k ≡ (2π)−3∫ dk0d2k and ({int}_{q}equiv {(2pi )}^{-3}int,d{q}_{0}^{{prime} }{d}^{2}{{boldsymbol{q}}}). Σex and Γ are the self-energy and vertex functions due to interfacial spin exchange coupling, respectively. We define a modified interfacial coupling strength (tilde{J}={J}_{1}{(16pi {v}_{{{rm{F}}}}Nsqrt{D})}^{-1/2}) and all the calculations below are provided up to leading order in ({{mathcal{O}}}({tilde{J}}^{2})). Moreover, to proceed analytically, we firstly focus on the the low frequency limit (| {q}_{0}| ll {xi }_{{{rm{b}}}}^{-2}equiv -{gamma }_{{{rm{g}}}}H). At the end of the section, we present the results for (| {q}_{0}| sim {xi }_{{{rm{b}}}}^{-2}equiv -{gamma }_{{{rm{g}}}}H) and provide the detailed derivations in Supplementary Note 3.

We start with the SE diagram in Eq. (15) by evaluating the self-energy function Σex. In the FM phase with a short correlation length ξb ≪ 1, the self-energy function is given by

In the low frequency limit (| {q}_{0}| ll {xi }_{{{rm{b}}}}^{-2}), we approximate the bare magnon Green function as ({G}_{0}^{-1}({{boldsymbol{q}}},{q}_{0})simeq i{q}_{0}-D{q}_{y}^{2}-{xi }_{{{rm{b}}}}^{-2}-alpha | {q}_{0}| ). Substituting this expression into Eq. (15) and carrying out the k-integral, we obtain

where the functional difference is defined as (Delta {{mathcal{M}}}(x,y)equiv {{mathcal{M}}}(x-y)-{{mathcal{M}}}(x)), and a is the power of the frequency dependence in the renormalized fermionic Green function, which has been previously defined. Next, we evaluate the V diagram in Eq. (15) starting from the vertex function

Similarly, by substituting this expression into Eq. (15) and carrying out the k-integral, we obtain

From Eq. ((17), (19)), we conclude that the contributions from SE and V diagrams are proportional to each other at the QCP in the presence of the NFL self-energy, which leads to

We remark that (i) the generic scaling exponent of the uniform spin susceptibility in Eq. (9) can be explicitly expressed as dχ = 2(z − d) = 2; (ii) This proportionality has been justified previously in the Fermi liquid phase with well-defined quasiparticles40.

After analytic continuing to real frequency ik0 → ω + i0+, and evoking the correspondence in Eq. (8), we arrive at the retarded magnon self-energy correction in the regime (| omega | ll {xi }_{{{rm{b}}}}^{-2}), which reads

Accordingly, the FMR modulations, namely the resonance frequency shift and the enhanced Gilbert damping, acquire peculiar scalings in frequency

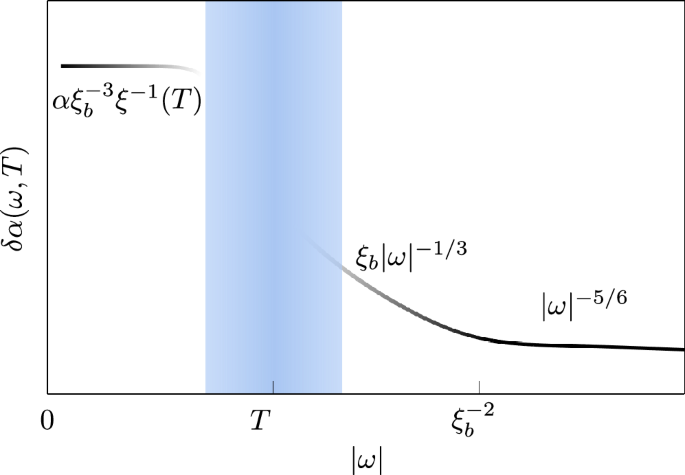

These power scalings are schematically plotted in Fig. 4 and are subjected to experimental validations. In the low energy and zero temperature limit: T < ∣ω∣ < ωc, the diverging coefficient δα indicates a different spin relaxation mechanism, which is in sharp contrast to the conventional linear-in-ω Gilbert damping. The exponents reflect the universal scaling behavior near the Ising nematic QCP in the dynamic limit. Near the resonant frequency (| omega | sim {xi }_{{{rm{b}}}}^{-2}), we show that [see Supplementary Note 3a] one can simply replace ξb in Eq. (22), which leads to (delta alpha sim {{rm{sgn}}}(omega )| omega {| }^{-5/6}). The FMR modulations take distinct set of scaling forms where the enhanced Gilbert damping coefficient becomes even more divergent. Finally, we point out that by comparing with the quasiparticle weights, the FMR modulations capture the disappearance of the quasiparticles in the low-energy limit.

The frequency and temperature dependence of the enhanced Gilbert damping coefficient ∣δα(ω, T)∣ is plotted in distinct regimes. The low-frequency(∣ω∣ < T, left) and high-frequency(∣ω∣ > T, right) regimes are separated by a blue shaded region.

FMR modulations at finite temperatures

The finite-temperature properties of NFLs in the quantum critical regime mediated by the Ising nematic QCP cannot be simply inferred from the zero-temperature results. The quantum fluctuation of the bosons obeys the ω/T scaling rule and leads to ({T}^{frac{2}{3}}) dependence for fermion self-energy; while, the contribution from thermal fluctuation is drastically different and dominates at low temperatures41. Importantly, it is demonstrated that vertex correction is subdominant when both thermal and quantum fluctuations are included42. As a result, one can write down the finite temperature version of Eliashberg equations which leads to the solution

where a and b are nonuniversal constants. The boson correlation length and electron scattering rate scale as ({xi }^{-1}(T) sim sqrt{Tln ({epsilon }_{{{rm{F}}}}/T)}) and (gamma (T) sim sqrt{T/ln ({epsilon }_{{{rm{F}}}}/T)}), respectively. We note that the expressions in Eq. (23) can not be deduced from the opposite T = 0 limit by applying the ω/T scaling. This is due to the T-dependence of the boson correlation arising from the dangerously irrelevant boson interactions. The imaginary part of the retarded fermion self-energy at T ≫ ∣ω∣ is derived as ({gamma }_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}}}}(T)={lambda }^{2}{d}_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}}}}^{2}Txi (T)/(4{v}_{{{rm{F}}}}sqrt{a})) for T ≪ T0. The upper energy bound ({T}_{0}={epsilon }_{{{rm{F}}}}{e}^{-{lambda }^{2}/{v}_{{{rm{F}}}}^{2}}) is specified by the condition (| {gamma }_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}}}}(T)| ll {xi }^{-1}(T){v}_{{{rm{F}}}}/sqrt{a}) within which the solutions in Eq. (23) hold. Moreover, we focus on the quantum critical regime (| omega | ll | {gamma }_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}}}}(T)| ) where the fermion self-energy overwrites the bare dynamics. The finite-T expression in Eq. (23a) can be further simplified as ({{rm{Im}}}{g}_{{{rm{R}}}}({{boldsymbol{k}}},omega )simeq {gamma }_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}}}}(T)/left[{({v}_{{{rm{F}}}}{k}_{x})}^{2}+{gamma }_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}}}}^{2}(T)right]).

In parallel with the previous section, we evaluate the uniform spin susceptibility in the quantum-critical finite-temperature fan from the SE+V diagrams. The calculation details are written in Supplementary Notes 4 and 5. Similarly, we first calculate the fermion self-energy due to interfacial spin exchange interaction where the local moments in FL are in the FM ordered phase with small correlation length ({xi }_{{{rm{b}}}}^{-2}gg T(gg | omega | )). The imaginary part of retarded component is given by

Using the Lehmann representation, we obtain the expression at Matsubara frequencies as

We note that the dominant contribution in the frequency integral comes from the finite-temperature regime approximately bounded by ∣ω∣≤T. Then, we substitute this expression into ISE(q0, T) and sum over the Matsubara frequencies, which yields

For the V diagram, we first calculate the vertex function,

where the bare magnon self-energy at finite-T is approximated as ({{rm{Im}}}{G}_{0}({{boldsymbol{q}}},Omega )=-alpha Omega /[{(D{q}_{parallel }^{2}+{xi }_{{{rm{b}}}}^{-2}-Omega )}^{2}+{alpha }^{2}{Omega }^{2}]simeq -alpha Omega /{(D{q}_{parallel }^{2}+{xi }_{{{rm{b}}}}^{-2})}^{2}). Substituting this expression into Eq. (15) and carrying out the k-integral, we obtain:

By comparing Eqs. ((26), (28)), we conclude that the proportionality between SE and V in Eq. (20) continuities to hold at finite temperatures in the quantum critical regime (| {q}_{0}| ll | {gamma }_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}}}}(T)| ).

Finally, we arrive at the retarded finite-temperature magnon self-energy at leading order in ({{mathcal{O}}}({tilde{J}}^{2})), which reads

where the real part is at the next order taking a form ( sim -({omega }^{2}{T}^{2})/{gamma }_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}}}}^{3}(T)) and is therefore omitted. This expression is consistent with the generic scaling form in Eq. (10) with ({d}_{chi }^{{prime} }=-2) at finite temperatures. Accordingly, the enhanced Gilbert damping coefficient is given by

and the resonant frequency shift vanishes δH ≃ 0 in the quantum critical fan region, which are schematically plotted in Fig. 4. We note that, in the quantum critical fan at finite-T, the Gilbert damping mechanism is restored, in contrast to the divergent Gilbert damping coefficient at T = 0 in Eq. (22). The information of the correlation length can be extracted from the FMR modulations which, at the same time, reflects the non-quasiparticle nature of the NFL metal and the underlying QCP. To see this, we evaluate the real part of the fermionic self-energy ({{rm{Re}}}{Sigma }_{{{rm{F}}}}({{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}}},omega ) sim -{d}_{{{{boldsymbol{k}}}}_{{{rm{F}}}}}^{2}omega xi (T)) for ∣ω∣ < T < ωc which leads to a vanishing quasiparticle weight due to the divergent correlation length [see Supplementary Note 6]

Discussion

We have presented a practical implementation of the magnetic heterostructure that probes the many-body spin/charge correlations. We study the FMR-driven spin pumping effect at the interface of NFL/FI heterostructure in the absence of quasiparticles. The NFL metal is induced near a Pomeranchuk-type of QCP in the charge channel; while, the dynamic spin correlation function of the NFL metal is non-vanishing and acquires universal power-law scalings in frequency and temperature domains, due to its interfacial exchange coupling to the adjacent FI. The experimental measurable FMR modulations, namely the resonance frequency shift and the enhanced Gilbert damping, convey valuable information characterizing the NFL behaviors and the disappearance of the quasiparticles. We conclude that the spintronics experiments, particularly spin pumping, can take full advantage of the magnetic heterostructure, meanwhile, shed light on the non-quasiparticle feature of spin relaxation in NFLs. Our proposal is also helpful in reconciling the current theoretical debates in the scaling forms of dynamic correlation functions near Ising nematic QCP.

The magnetic heterostructure is far from simple stacking of two different materials. The heterostructure by design breaks inversion symmetry, thus, allowing the existence of anti-symmetric spin exchange interaction, which is also known as the Dzyaloshinski–Moriya interaction (DMI). On one hand, the DMI can drive the magnetic insulators into forming more complex magnetic orders, such as the skyrmion lattice structures where local magnetic moments swirl spatially in a non-collinear way while forming a periodical lattice. The formation of more complex magnetic ordered states inevitably makes the phenomena of the spin pumping effect more diverse and interesting. It has already been reported that the magnetic fluctuation of the skyrmion lattices can mediate exotic type of electron interaction in normal metals. Owing to the non-collinear nature of the magnetic ground state, topological superconductivity can be induced directly43. The investigation of the competiting role between 2D topological superconductivity and novel type of NFLs is an intriguing topic. Moreover, the heterostructure setup offers an ideal platform for studying the spin pumping effect, which is particularly appealing to the spintronics community. On the other hand, the DMI is an essential ingredient when the magnetic insulator approaches its criticality. Infinite many critical bosons can simultaneously reach criticality due to the presence of DMI in three-dimensional chiral magnet30 as well as 2D magnetic heterostructure interface31. The infinite many critical boson can induce a different type of NFL state for the itinerant magnets nearby29,30,31,44,45.

Finally, we remark on the non-equilibrium theoretical framework adopted in the present study. The FMR modulations are derived perturbatively in terms of interfacial exchange coupling strength J1 in the Keldysh representation. In contrast, the self-energy correction of the NFL is independent of J1, that is, the stability of the NFL state is assumed as prior. From a theoretical point of view, it is greatly desired that the coupled two sides of the magnetic heterostructure are solved self-consistently; yet, it poses great difficulty. Thanks to the development of Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev (SYK) model46, the magnetic exchange interaction can be regarded as a random variable in fictitious flavor space. The replica trick used in solving SYK model can lead to a solvable equation set for the entire magnetic heterostructure. The mutual interactions between the itinerant magnets and driven magnetic insulator can be determined self-consistently via numerical calculations. This greatly improves the current theoretical treatments in analyzing the spin pumping effect, particularly, the non-steady non-equilibrium spin dynamics.

Responses