Stabilization of a miniprotein fold by an unpuckered proline surrogate

Introduction

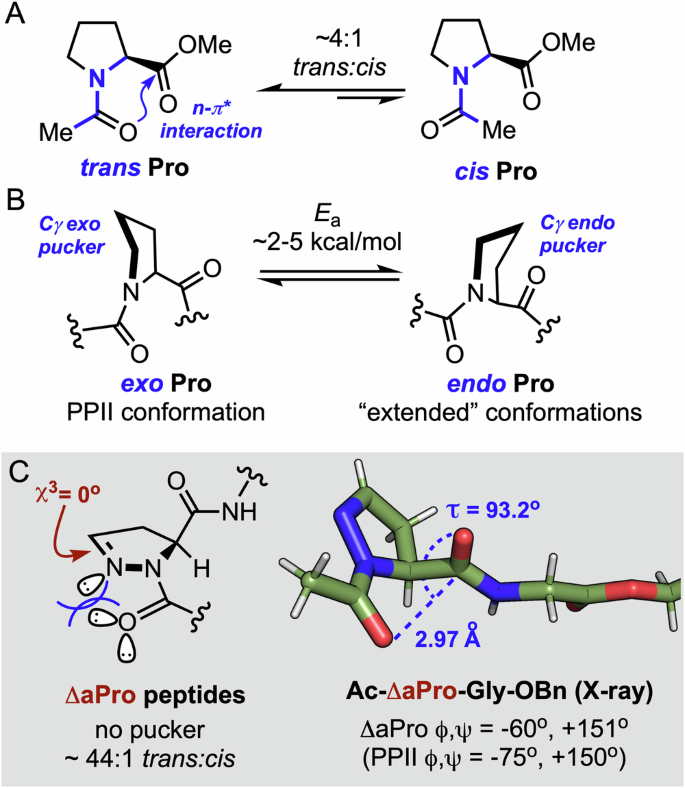

Understanding the intrinsic conformational preferences of non-canonical amino acids is essential for informing the rational design of new proteomimetics1. Surrogates of proteinogenic residues can serve as conformational probes for factors that influence protein folding, and impart host sequences with enhanced stability, catalytic activity, and/or biological function. Proline (Pro) holds a special place among the canonical amino acids due to a backbone ϕ dihedral angle restricted to ~−65° and an increased propensity for prolyl tertiary amides to adopt the cis geometry (Fig. 1A) that is highly disfavored for secondary amides2,3. In addition, the pyrrolidine ring of Pro primarily adopts two distinct puckered envelope conformations, denoted as endo or exo depending on the spatial relationship between Cγ and the α-carboxy substituent (Fig. 1B)4,5. Although the barrier to endo−exo interconversion is relatively low, the puckered conformations of Pro and its substituted analogs correlate with stereoelectronic effects that favor specific PPII or extended conformations6,7,8,9,10,11. These structural characteristics underlie the central role that Pro plays in mediating protein folding and stability.

A N-Terminal amide rotamer and B pyrrolidine ring pucker equilibria in prolyl peptides. C Conformational features of dehydro-δ-azaproline (ΔaPro) and X-ray structure of a ΔaPro dipeptide (phenyl ring omitted for clarity).

Proteins harboring non-canonical proline analogs have offered insights into the structure, dynamics, and function of several biomolecules12. For example, γ-substituted prolines have been employed in mimetics of barstar13, collagen14,15,16, insulin17,18, β2-microglobulin19, thioredoxin20,21, and several other proteins12 due to the influence of the substituent group on ring puckering and trans−cis isomerization. Other surrogates including lower or higher ring homologs17,18,22, Cα/δ-alkylated prolines23,24, α/γ-azaprolines25,26, δ-CF3-pseudoproline27, γ-thiaproline28,29,, γ-silaproline30,31, and acyclic N-alkyl (peptoid) residues32,33,34 have also been used to modulate protein structure and function. Our group recently described the synthesis and structural characterization of dehydro-δ-azaproline (ΔaPro), a novel unsaturated analog of Pro featuring a dehydropyrazine ring (Fig. 1C)35. With a χ3 dihedral angle near 0o, the ΔaPro heterocycle lacks the pucker observed in Pro or its saturated δ-azaproline analog. When incorporated into peptides, ΔaPro forms an N-acylhydrazone backbone linkage with a lower isomerization barrier relative to the tertiary amide formed by Pro but a remarkably high trans rotamer bias due to lone pair repulsion in the cis geometry. These considerations suggest that ΔaPro could serve as a tool to assess the relative importance of backbone torsional propensity and ring pucker for protein folding and stability.

Here, we describe the synthesis and structural analysis of a PPII-α miniprotein featuring ΔaPro substitutions. Our goal was to evaluate ΔaPro as an unnatural surrogate of native residues that adopt proline-like backbone conformations within a tertiary fold. Using a combination of biophysical techniques, we demonstrate that the unpuckered ΔaPro residue favors PPII conformation and maintains or enhances the thermal stability of the avian pancreatic polypeptide (aPP) when incorporated at select positions. An aPP variant featuring three ΔaPro substitutions, including one in the Pro switch region linking the two secondary structures, exhibits the highest thermal stability among the synthesized analogs. Our results establish ΔaPro as a conformational surrogate of Pro and demonstrate that backbone torsional preferences outweigh ring puckering as contributors to enhanced stability in the aPP system.

Results and discussion

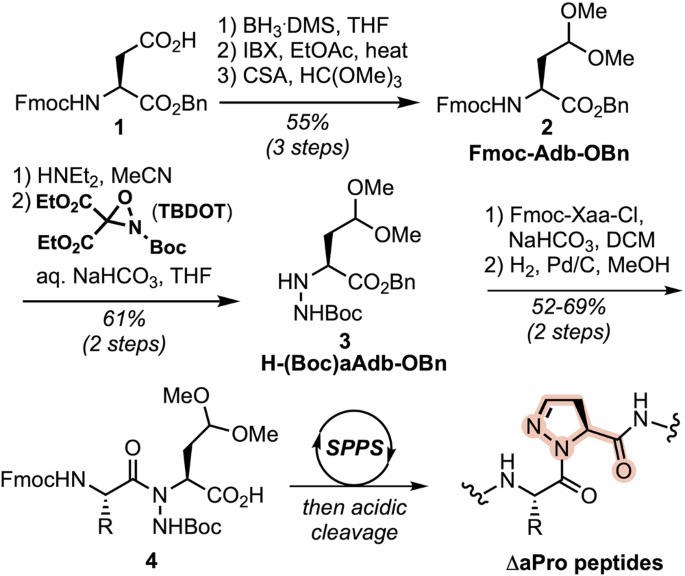

Synthesis of peptides containing ΔaPro

We previously reported the incorporation of ΔaPro into peptides on solid support using an N-aminated homoserine building block35. The dehydropyrazine ring was formed via an on-resin Mitsunobu reaction, followed by peptide cleavage/deprotection and subsequent oxidation of the Cγ-Nδ bond in aqueous peroxide. Here, we developed a more robust synthesis of ΔaPro-containing peptides wherein the heterocycle is formed during cleavage from the resin. Our synthesis began with side chain manipulation of Fmoc-Asp-OBn (1) to generate the aldehyde, which was then protected as a dimethyl acetal to provide 2-amino-4,4-dimethyoxybutyric acid (Adb) derivative 2 in 55% overall yield (Scheme 1). Fmoc deprotection and N-amination of the primary amine with 2-tert-butyl-3,3-diethyl-oxaziridine-2,3,3-tricarboxylate36 afforded compound 3 in 61% yield over 2 steps. The N-aminated Adb derivative was then reacted with a variety of Fmoc-protected amino acid chlorides. Hydrogenolysis of the resulting benzyl esters afforded a series of protected dipeptides (4) suitable for SPPS (see Supporting Information for details). Peptide synthesis was carried out on Rink amide MBHA resin using standard Fmoc-based protocols and HCTU/NMM activation. Cleavage from the resin and global deprotection under acidic conditions unmasks the side chain aldehyde, leading to ΔaPro ring closure. The efficiency of this cyclization was verified by subjecting one of our dipeptide building blocks, Fmoc-Gln(Trt)-(Boc)aAdb-OBn, to the same conditions used for peptide cleavage (see Supporting Information for details).

Synthesis of (N-amino)-2-amino-4,4-dimethoxybutyric acid (aAdb) dipeptide derivatives and incorporation into ΔaPro-containing peptides.

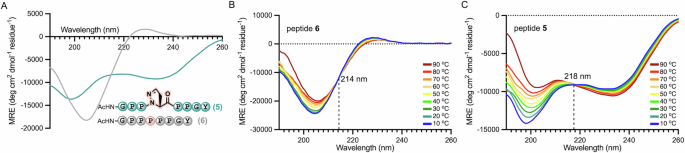

Circular dichroism of a ΔaPro PPII model peptide

We first attempted to measure the PPII propensity of ΔaPro using the octapeptide model system developed by Brown and Zondlo37. This PPII strand consists of a pentaproline core sequence flanked by Gly residues and with Tyr at the C-terminus to aid with quantification by UV. We synthesized peptide 5, featuring a ΔaPro guest residue at the center of the pentaproline tract, and compared its circular dichroism (CD) spectrum to that of parent octapeptide 6. Substitution of Pro5 with ΔaPro resulted in a CD spectrum that lacked the positive band near 228 nm typical of PPII folds and showed two moderate intensity negative bands at 236 nm and 198 nm that do not correspond to common peptide secondary structures (Fig. 2A). Modifications to Pro residues within folded PPII domains have previously been shown to give rise to unusual CD signatures, including loss of the characteristic positive band and a blue-shifted negative band38,39. Replacement of the central tertiary amide in 6 for an N-acylhydrazone moiety would also be expected to alter the chromophoric properties of 5. Whereas peptide 6 exhibited only slightly diminished positive and negative band intensities upon thermally induced transition from PPII to random coil conformation, peptide 5 underwent a more pronounced change in spectral signature with a well-defined isodichroic point at 218 nm (Fig. 2B, C). Although the CD signature of 5 precludes straightforward interpretation, these results suggest that 5 adopts a well-defined structure and undergoes a shift in population between two different conformers as a function of temperature.

A Far UV CD spectra of PPII octapeptides 5 (teal) and 6 (gray) at 25 °C. Variable temperature CD wavescans for (B) peptide 6 and C peptide 5. All samples were analyzed at 150 µM in 5 mM sodium phosphate, 25 mM KF, pH 7.0.

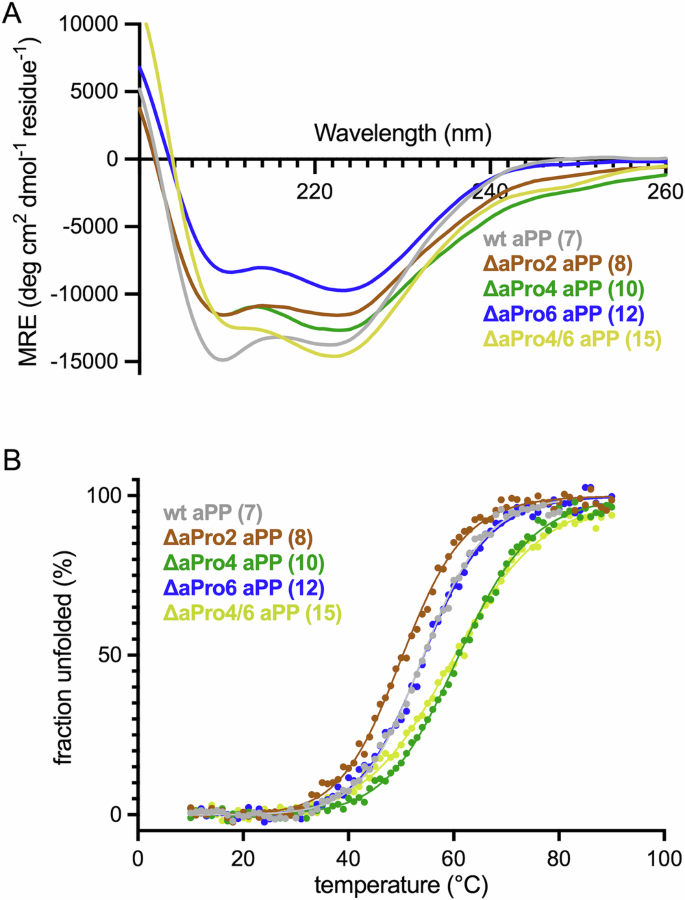

Thermal stability of PPII-substituted aPP analogs

We turned to aPP as a miniprotein model to investigate the impact of ΔaPro substitution in the context of a tertiary fold. aPP is a 36-residue peptide hormone whose structure features a hydrophobic core resulting from tight packing of PPII and α-helical secondary structures40,41,42. aPP also exhibits quaternary structure owing to reversible and pH-dependent dimerization43. The small size and unusual stability of the aPP fold has made it a versatile starting point in the design of thermally stable variants44,45,46, high-affinity protein and DNA ligands46,47,48,49,50,51, and non-canonical proteomimetics52,53. The presence of buried and solvent-exposed PPII residues (2−8), as well as a loop Pro13 residue that demarcates the transition from α-helix to PPII secondary structure, make aPP particularly useful for investigating the conformational impact of unnatural Pro analogs in distinct local environments.

We carried out a PPII helix scan across residues 2−8 in aPP in order to evaluate the effect of ΔaPro incorporation on folding. Table 1 lists PPII helix-substituted analogs synthesized for the current study. Each peptide was purified using RP-HPLC and their identities were confirmed by HRMS.

All peptides were analyzed by far UV CD at 10 °C at a concentration of 30 µM. Wild-type aPP exhibits CD minima near 208 and 222 nm resulting from a combination of α-helical and PPII secondary structures. Substitution of Ser3 (9), Pro5 (11), Tyr7 (13), and Pro8 (14) with ΔaPro led to a significant decrease in the magnitude of the CD signature (Supplementary Fig. 1A), suggesting substantial disruption of the native fold from modification at these sites. In wild-type aPP both Pro5 and Pro8 engage in hydrophobic knob-in-hole interactions with the α-helix that stabilize the tertiary fold. The introduction of the more polar ΔaPro side chain at these positions likely disrupts the close packing of the PPII helix to the α-helix. The observed effect of modification at Tyr7 is consistent with previous studies demonstrating the importance of this residue for dimer stability44. The CD spectra of aPP variants with ΔaPro in place of Pro2 (8), Gln4 (10), or Thr6 (12) maintained native-like tertiary structure, albeit with slightly diminished minimum band intensities relative to wild-type aPP (Fig. 3A). This demonstrates that ΔaPro is well-tolerated at several positions within the PPII helix of aPP.

A CD spectra and B representative plots of fraction folded as a function of temperature determined by CD melts for peptides 7 (gray), 8 (brown), 10 (green), 12 (blue), and 15 (yellow) at 30 μM in 4 mM sodium phosphate, 155 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. For thermal melts, molar ellipticity was monitored at 222 nm and fitted curves were derived from non-linear regression.

We next measured the thermal stability of each well-folded analog by monitoring ellipticity at 222 nm from 10 °C to 90 °C (Fig. 3B). The aPP variants exhibited cooperative unfolding transitions with a range of temperature midpoint (Tm) values (Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Analog 8, harboring ΔaPro at position 2, exhibited a decrease in thermal stability (49.7 °C) relative to wild-type aPP (54.2 °C). As with the ΔaPro5 and ΔaPro8 analogs, this is likely due to disruption of hydrophobic interactions involving Pro2 in wild-type aPP. In contrast, substitution of Gln4 for ΔaPro4 (10) resulted in a significant increase in thermal stability (61.9 °C). Replacement of Thr6 with ΔaPro (12) afforded an analog with similar thermal stability to wild-type aPP. Since analogs 10 and 12 feature replacement of non-Pro residues, we synthesized analogs 16 and 17 to directly compare the effect of ΔaPro versus Pro substitution at these positions. Pro4 aPP (16) exhibited similar thermal stability to ΔaPro4 aPP (10), while Pro6 aPP (17) was less stable than the corresponding ΔaPro6 analog (12). These data demonstrate that ΔaPro is an effective surrogate for both Pro and non-Pro residues at positions 4 and 6 within the PPII helix and is superior to Pro at some sites. Finally, we synthesized a disubstituted analog incorporating ΔaPro at positions 4 and 6 (15). This peptide exhibited thermal stability essentially equivalent to that of ΔaPro4 aPP (60.9 °C).

NMR-derived solution structures of PPII-substituted aPP analogs

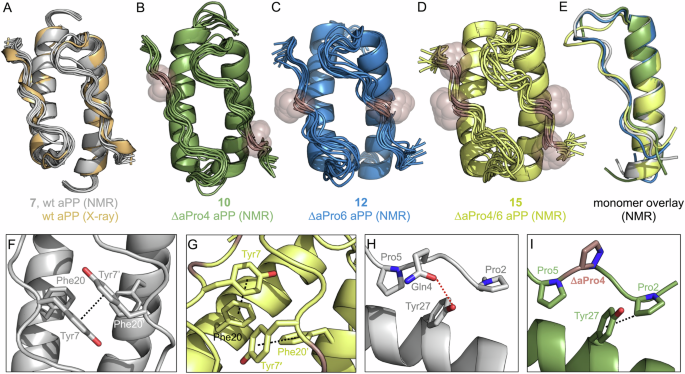

In order to gain insight into how ΔaPro substitutions impact the aPP fold, we used multidimensional NMR spectroscopy to determine high-resolution structures of the parent peptide (7), ΔaPro4 aPP (10), ΔaPro6 aPP (12), and the ΔaPro4/6 aPP double mutant (15). Full proton resonance assignments were carried out on the basis of 1H/1H COSY, TOCSY, and NOESY spectra acquired in 9:1 H2O/D2O with 50 mM d3-AcOH. Hα chemical shift values for residues within the putative PPII and α-helical regions were consistent across the three peptides (Supplementary Fig. 3), indicating a similar fold. We used simulated annealing with NMR-derived restraints to generate high-resolution structures of each peptide as their symmetric homodimers. At NMR concentrations (2 mM) the peptides were assumed to exist as dimers on the basis of sedimentation equilibrium analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 1). A subset of NOE correlations attributable to homodimeric structures and incompatible with intraprotomer contacts were evident in the NOESY spectra. The structural ensembles in Fig. 4A–D are comprised of the 10 lowest energy models for each folded peptide.

A Overlay of the NMR-derived dimeric structural ensemble of 7 (gray) and the reported X-ray structure of wild-type aPP (orange). B–D NMR-derived dimeric structural ensembles for ΔaPro-substituted aPP analogs 10 (green), 12 (blue), and 15 (yellow). ΔaPro residues in each structure are indicated with spheres. (E) Aligned lowest energy (state 1) monomer chains of 7, 10, 12, and 15. F Interchain Tyr7−Tyr7’ π−π interaction observed in the NMR structure (state 1) of wt aPP (7). G A shift in the Tyr7/Tyr7’ χ1 angle leads to intramolecular T-shaped π interactions with Phe20/Phe20’ in the NMR structure (state 1) of 15. H Intramolecular Gln4−Tyr27 H-bond observed in the NMR structure (state 1) of wt aPP (7). I Potential Pro2−Tyr27 CH−π interaction in the NMR structure (state 1) of ΔaPro4 aPP (10).

The calculated structures of parent peptide 7 were in close agreement with the high-resolution X-ray structure previously reported for aPP42 (1.2 Å backbone RMSD for residues 2−32). Similarities between the structures include a series of van der Waals contacts between inward-facing Pro residues in the PPII helix and hydrophobic side chains of the α-helix, as well as interprotomer interactions involving the aromatic side chains of Tyr7 and Phe20. The ΔaPro-substituted analogs each exhibit tertiary folds similar to that of the parent peptide. However, peptide 10, the most thermally stable monosubstituted analog studied here, exhibits reduced conformational heterogeneity at the N-terminus relative to aPP, maintaining canonical PPII backbone torsions through Pro2 (Supplementary Fig. 5). Disubstituted ΔaPro4/6 aPP analog 15 exhibited the greatest disorder across the NMR states, particularly in the loop region defined by residues 9−13 (2.4 Å intra-ensemble backbone RMSD for 15 vs. 0.9 Å for 7). Interestingly, the melting temperature of 15 was equivalent to that of 10, despite deviations from the type I β-turn characteristic of the loop region in several of its calculated structures (Fig. 4E).

In addition to perturbed loop conformation, the structures of 15 feature a significant shift in the orientation of the Tyr7 and Tyr7’ side chains at the dimer interface. In peptides 7, 10, and 12, these residues engage in a face-to-face π–π interaction thought to be important for dimer stability (Fig. 4F)42. The large change in Tyr7 and Tyr7’ χ1 angles observed in 15 (60% g−, 40% g+ for χ1 in the ensemble for 15 vs. 100% t for 7) results in a much greater intermonomer distance between the aromatic rings. Consequently, the Tyr7 side chain moves closer to the Phe20 side chain within the same protomer, potentially introducing a stabilizing intramolecular T-shaped π-π interaction (5.9 Å average distance between the ring centers) (Fig. 4G). The possibility exists that the apparent distortions in packing around Tyr7 in 15 are an artifact of the uncertainty in NMR structure determination of the symmetric dimer; however, other aspects of the biophysical data support the hypothesis that the altered quaternary interactions are genuine. Sedimentation equilibrium analysis showed a nearly fourfold increase in dissociation constant (Kd) for 15 relative to 7, resulting in a modest increase in monomer population at CD concentration (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 1). Stabilization of monomer folding through interactions involving Tyr7 and/or backbone rigidification through ΔaPro substitutions may explain the enhanced melting temperature of 15 despite apparent destabilization of the dimer assembly.

The majority of NMR-derived models for parent peptide 7 show an intramolecular H-bond between the side chains of Gln4 and Tyr27 (Fig. 4H). Additional evidence for the proximity of these residues can be found in the upfield shift of the Gln4 Hα (Supplementary Fig. 3) consistent with shielding by the aromatic side chain. We observed a significant enhancement in thermal stability when Gln4 was substituted for ΔaPro (in 10 and 15) or Pro (in 16). In the case of peptide 10, loss of this potential H-bond was attended by tighter hydrophobic packing between the PPII N-terminus and the α-helix (average distance of 4.5 Å for Pro2 Cβ to the Tyr27 ring center in 10 vs. 5.7 Å in 7) (Fig. 4I). While the proximity of Pro2 and Tyr27 in 10 is consistent with a potential CH−π interaction, the lack of a significant upfield shift of Pro2 side chain resonances argues against it. To test whether simple deletion of the Gln4 side chain was sufficient for stabilization of the aPP fold, we prepared the Gly4 analog (18) and carried out thermal denaturation studies. Peptide 18 exhibited a melting temperature 6.6 °C lower than that of wild-type aPP. These results suggest that backbone torsional preferences favorable to PPII conformation are important for the stabilizing effects of ΔaPro substitution. This is further supported by the enhanced thermal stability of 12 relative to Pro6 analog 17, both of which feature substitution of the solvent-exposed Thr6 residue within the PPII helix.

Synthesis and thermal stability of loop-substituted aPP analogs

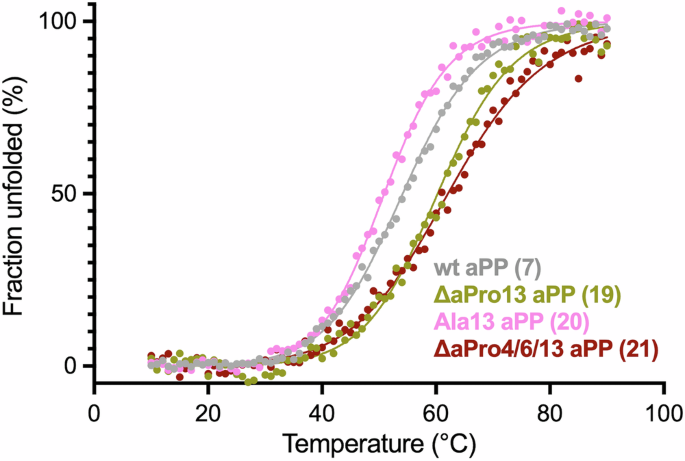

aPP and other PP-fold family members harbor a highly conserved Pro residue in the loop connecting the PPII and α-helices. Given its role in maintaining aPP tertiary structure, we investigated whether substitution of Pro13 for ΔaPro would result in a well-folded analog. The peptides in Table 3 were prepared on solid support following the same protocol as the aPP variants described above. Peptides 19 and 20 feature single residue substitution at position 13 (ΔaPro or Ala), while peptide 21 incorporates stabilizing ΔaPro mutations at positions 4 and 6 of the PPII helix in addition to ΔaPro13 substitution.

The CD spectral signatures of peptides 19−21 obtained at 30 μM exhibited minimum ellipticities near 208 and 222 nm that were consistent with the native fold of aPP (Supplementary Fig. 6). Thermal denaturation studies further revealed that substitution of Pro13 for ΔaPro significantly stabilizes the miniprotein (ΔTm of +7.0 °C for 19 versus 7) (Fig. 5, Table 4, and Supplementary Fig. 7). In contrast, substitution of Pro13 for Ala resulted in destabilization (ΔTm of −4.7 °C for 20 versus 7), confirming the importance of a cyclic residue in the loop region. Peptide 21, featuring ΔaPro substitution at residues, 4, 6, and 13 showed a +7.4 °C enhancement in thermal stability relative to wild-type aPP. The lack of an additive stabilizing effect upon the introduction of ΔaPro residues in both the loop and PPII regions might be explained by destabilization of quaternary structure, as determined by sedimentation equilibrium analysis (Supplementary Table 1). At the concentration employed for thermal denaturation experiments, analogs 19 and 21 were found to be 58% and 73% monomeric, respectively.

Representative plots of fraction folded as a function of temperature for peptides 7 (gray), 19 (olive), 20 (pink), and 21 (dark red) at 30 μM in 4 mM sodium phosphate, 155 mM NaCl, pH 7.4. Molar ellipticity was monitored at 222 nm, and fitted curves were derived from non-linear regression.

Molecular dynamics simulations

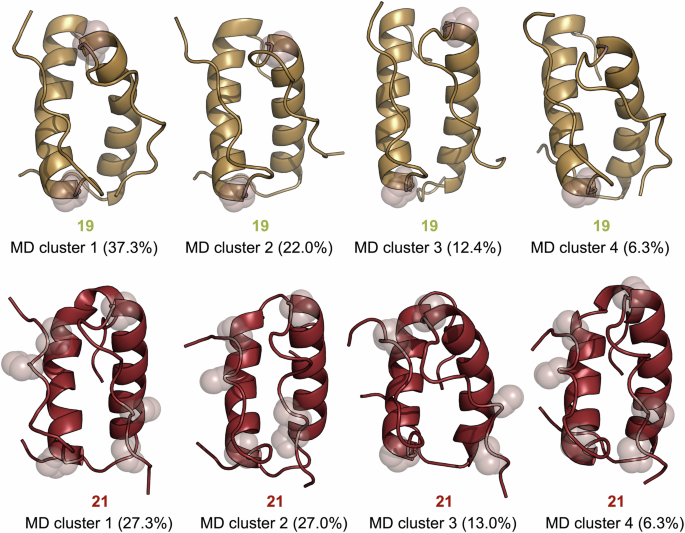

Our efforts to obtain NMR solution structures for aPP analogs substituted at Pro13 were unsuccessful due to a lack of convergence during simulated annealing. This may result from a greater heterogeneity in the system due to a more prevalent monomer/dimer equilibrium. We turned to molecular dynamics (MD) to gain insights into how the ΔaPro residues in each of our variants may be impacting structure. We first ran a 100 ns MD simulation for 7 using GROMOS software, starting from the published X-ray conformation of dimeric wild-type aPP. 50 ns simulations of monosubstituted analog 19 and trisubstituted analog 21 revealed secondary, tertiary, and quaternary structures similar to that of wild-type aPP (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 8). Low Cα atom root-mean-square fluctuations were observed across residues 3−30, with higher fluctuations evident at the termini (Supplementary Fig. 9). Analogs 10 and 15, which exhibit enhanced thermal stability relative to 7, also retained the expected dimeric structure throughout MD simulations (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Representative MD-derived structures of the four most populated conformational clusters (percentage of the population in parentheses) for ΔaPro aPP analogs 19 and 21. ΔaPro residues in each structure are indicated with spheres.

Ramachandran analysis of MD trajectories for substituted variants revealed that the conformation of ΔaPro at positions 4 and 6 in peptides 10, 15, and 21 exhibit significant increases in PPII population relative to the wild-type Gln4 and Thr6 residues (Table 5 and Supplementary Tables 2–6). While the PPII propensity of ΔaPro13 in 19 was similar to that of Pro13 in wild-type aPP, we observed a modest decrease in the case of trisubstituted variant 21. A similar decrease was also observed in ΔaPro4/6 aPP variant 15, suggesting that these PPII helix substitutions impact the backbone geometry of residue 13. This is further supported by NMR analysis showing perturbed loop conformation for disubstituted analog 15 (Fig. 4E). Trisubstituted peptide 21 also exhibited loss of several intermolecular H-bonds involving the sidechain of Gln4 present in 7 that may be important for dimer stability (Supplementary Table 7). Although 21 remained a dimer throughout the simulation, the 50 ns timescale may not be sufficient to capture potential loss of quaternary structure. The lower number of transient interchain polar contacts in 21 is also consistent with its significantly higher dimerization constant (58.2 μM) relative to 7 (1.31 μM).

Taken together, results from MD simulations support the notion that ΔaPro strongly favors PPII conformation, particularly relative to the acyclic Gln and Thr residues within the PPII fold. However, ΔaPro at position 13 exhibits similar or slightly lower PPII propensity than the native Pro. Access to alternative backbone conformations in the aPP loop region may allow for more optimal intramonomer packing of the PPII and α-helices, albeit at the expense of dimer interface interactions. Another likely contributor to the high thermal stability of 19 and 21 is the increased trans amide rotamer propensity of ΔaPro relative to Pro35. Lone pair repulsion between Nδ of ΔaPro13 and the preceding Ala12 carbonyl oxygen presumably destabilizes the cis rotamer unfolded state of aPP. However, this effect and its importance for the stability of loop-substituted ΔaPro variants would not be captured in the MD simulations or NMR structure calculations described above. More detailed insights into the thermodynamic basis for the observed thermal stability differences thus remains a subject of future investigation.

Conclusions

In summary, we investigated the impact of a novel unpuckered proline surrogate on the tertiary and quaternary structure of the aPP miniprotein. As part of this study, we developed a synthetic approach that allows for incorporation of ΔaPro into peptides and proteins using standard solid-phase protocols. A complete PPII residue scan of aPP revealed that ΔaPro substitution is well tolerated at several sites and confers enhanced stability relative to Thr4 in the wild-type protein. We found that Pro → ΔaPro substitution in the loop connecting the PPII and α-helical motifs also enhances thermal stability. Though not synergistic, a significant increase in melting temperature was observed upon incorporation of ΔaPro at three candidate positions within a single aPP variant.

High-resolution NMR structures and MD simulations show that ΔaPro readily adopts PPII conformation and maintains the native aPP tertiary fold. These results suggest that ring puckering may be less important for thermal stability than trans amide propensity and ϕ torsional restriction in the aPP system. However, our findings also suggest the structural impact of ΔaPro substitution should be considered alongside perturbations to non-covalent interactions in the wild-type structure. For example, ΔaPro substitution of PPII residues that define the hydrophobic core or engage in critical π-π interactions were found to significantly destabilize aPP. The increased polarity of the dehydropyrazine ring relative to pyrrolidine may contribute to disruption of native structure at these positions. Sedimentation equilibrium analysis also suggests that secondary and tertiary structure stabilization imparted by ΔaPro significantly outweighs disruption of quaternary structure, particularly in the case of loop-substituted analogs. These considerations highlight the importance of strategic incorporation of conformational surrogates within complex protein folds.

The current study serves to expand the repertoire of Pro surrogates for use in proteomimetic design. Beyond increased thermal stability, the introduction of multiple backbone-modified surrogates such as ΔaPro paves the way toward hybrid proteins with enhanced resistance to proteolysis. The high trans rotamer propensity and low isomerization barrier of the backbone N-acylhydrazone bond also suggest that ΔaPro could be useful in modulating protein conformational dynamics and folding/misfolding pathways. Efforts to employ ΔaPro and related monomers in these and other biologically relevant contexts are currently underway in our laboratory.

Methods

General information for peptide synthesis

Automated solid-phase peptide synthesis was carried out on a CEM Liberty Blue peptide synthesizer and a PurePrep Chorus peptide synthesizer using ProTide Rink amide resin (100-200 mesh, 0.63 mmol/g, 0.1 mmol scale). In addition to protected N-aminated dipeptide building blocks (4), the following derivatives suitable for Fmoc SPPS were used: Fmoc-Gly-OH, Fmoc-Pro-OH, Fmoc-Ser(tBu)-OH, Fmoc-Gln(Trt)-OH, Fmoc-Thr(tBu)-OH, Fmoc-Tyr(tBu)-OH, Fmoc-Asp(tBu), Fmoc-Ala-OH, Fmoc-Val-OH, Fmoc-Glu(tBu)-OH, Fmoc-Leu-OH, Fmoc-Ile-OH, Fmoc-Arg(Pbf)-OH, Fmoc-Phe-OH, Fmoc-Asn(Trt)-OH, Fmoc-His(Trt)-OH. Fmoc deprotection steps were carried out by treating the resin with a solution of 20% (w/v) piperidine/DMF once at room temperature (5 min), then at 75 °C (2 min). After Fmoc deprotection the resin was washed with DMF 4×. Coupling of Fmoc-protected building blocks was achieved using 5 equiv. HCTU (0.25 M in DMF), 10 equiv. NMM (1 M in DMF), and 5 equiv. of Fmoc-protected amino acid or dipeptide building block (0.2 M in DMF) at 50 °C (10 min) then at 75 °C (5 min). Deprotection and coupling steps were repeated until peptide synthesis was complete and then a final Fmoc deprotection was run to remove Fmoc from the N-terminus. The resin was transferred to a suitable vessel, washed with DCM (5 mL × 4) and dried under vacuum. Cleavage from the solid support and global deprotection was effected by incubating the dried resin in 10 mL of TFA:TIPS:H2O (95:2.5:2.5) for 2.5 h. The resin was filtered, and the filtrate was collected in a 50 mL centrifuge tube. The resin was washed with DCM (10 mL), filtered, and concentrated, and crude peptides were precipitated from the concentrated solution by the addition of cold Et2O (45 mL). The mixture was centrifuged and the supernatant decanted. The pellet was washed with Et2O (25 mL × 2) and dried thoroughly under vacuum. All peptides were purified by preparative HPLC with a reverse-phase column (C12 or C18, 250 mm × 21.2 mm, 4 μm, 90 Å) using linear gradients of MeCN in H2O (mobile phases modified with 0.1% formic acid) over 30 min.

Circular dichroism

All aPP analogs (7−21) were prepared by dissolving lyophilized powder in 4 mM sodium phosphate, 155 mM NaCl, pH 7.4, at a concentration of 30 µM. Single-strand PPII peptides 5 and 6 were dissolved in 5 mM Na3PO4, 25 mM KF (pH 7.0) at a concentration of 150 µM. The concentrations were determined by UV absorbance at 280 nm using the Beer–Lambert equation (A = ε × b × C), where A is the absorbance, ε is the molar absorptivity of Tyr at 280 nm (1490 L mol−1 cm−1), b is the pathlength (1 cm), and C is peptide concentration (mol L−1). CD spectra were acquired using a JASCO J-1700 CD spectrometer in a 1 mm path length quartz cell with 2 s digital integration time, 1 nm bandwidth, 0.5 nm datapitch, and a scan speed of 100 nm/min at 20 °C. Mean residue ellipticity at a given wavelength (MRE; deg cm2 dmol−1 residue−1) was calculated based on the equation MRE = θ/(10 × b × M × n), where θ is ellipticity (mdeg), b is the path length (cm), M is the peptide concentration (mol L−1), and n is the total number of residues. Temperature-dependent CD spectra were acquired using the same parameters from 10 to 90 °C in 1 °C increments at a ramp rate of 2 °C per minute. Non-linear regression curves and melting temperatures were calculated according to the method described by Shortle and coworkers54.

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Analytical ultracentrifugation experiments were performed using peptide solutions prepared in a Tris buffer (25 mM Tris base, 50 mM NaCl, pH 8.0) at concentrations of 2−160 µM. Sedimentation equilibrium experiments were performed in a ProteomeLab XL-I AUC (Beckman) at 25 °C. Samples were spun at 15,000 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C prior to AUC analysis. Double sector cells equipped with 1.2 cm charcoal-epon centerpieces (Beckman) were loaded with 345 µL of sample. Samples were spun at 19,000, 27,000, and 42,000 rpm to equilibrium. Absorbance at 230 and 280 nm was measured with a 0.001 cm radial step size and 10 replicates. The peptides’ partial specific volume, buffer density, and viscosity at 25 °C were calculated using SEDNTERP. The data was analyzed globally using the monomer-dimer association model in Sedphat. Data was plotted using GUSSI.

NMR structure calculation

All NMR experiments were conducted on a Bruker Advance II 800 MHz spectrometer. NMR samples consisted of 2 mM peptide, 50 mM AcOH-d3, 0.05 mM sodium trimethylsilylpropanesulfonate (DSS) in H2O:D2O (9:1) at pH 4.1. Spectra were acquired at 27 °C. Two-dimensional homonuclear NOESY (250 ms and 100 ms mixing time) and TOCSY (80 ms mixing time) spectra were collected with 4096 data points in the direct dimension and 512 data points in the indirect dimension. Resonances were assigned manually by standard methods using NMRFAM-SPARKY and POKY software packages55,56. NMR structure calculations were carried out by simulated annealing using the program Ambiguous Restraints for Iterative Assignment (ARIA, version 2.3)57 with Crystallography & NMR System (CNS, version 1.21)58. Geometric restraints for the ΔaPro residue were assembled based on a previously reported crystal structure of a short peptide containing this monomer (CCDC 1970060)35. ARIA run parameters were modified from defaults to improve convergence as previously described59. Spin diffusion correction was employed60, with an estimated correlation time of 5.3 ns calculated based on a crystal structure of the aPP dimer (PDB 1PPT) using the program HYDROPRO61. Hydrogen bond restraints for the α-helical region were prepared based on manual inspection of medium-range i → i + 3 correlations in the NOESY. NOE distance restraints were generated in fully automated fashion by the ARIA software starting from a set of 1H resonances and integrated, unassigned peak lists from the two different mixing time NOESY experiments.

To improve convergence in the determination of the structure of the symmetric homodimer, each calculation proceeded in three stages. In run 1, a subset of the NOESY peaks that were determined as likely arising from the dimer and incompatible with the monomer were manually identified and excluded. The remaining cross-peaks were all specified as intra-chain and used to generate a structure ensemble for the monomer. In run 2, all NOESY peaks were included but manually specified as intra- or inter-molecular and used to calculate an initial structure of the dimeric complex (C2 symmetry, NCS enabled). The starting structure for run 2 consisted of two copies of the monomer output from run 1 separated by ~30 Å. In run 3, all NOESY peaks were included and set as ambiguous with respect to being inter- or intra-molecular. The starting structure for run 3 consisted of the ensemble obtained from run 2, and network anchoring was enabled for iterations 0–39. The set of 10 lowest energy structures resulting from run 3 was taken as the reported NMR structure ensemble of each peptide (Supplementary Tables 7–10). Ensemble coordinates and additional experimental data are deposited in the PDB (9D99, 9D9A, 9D9B, and 9D9C) and BMRB (31194, 31195, 31196, 31197).

Molecular dynamic simulations

MD simulations were carried out using the GROMOS biomolecular simulation software62,63,64 and the GROMOS 54A7 force-field parameter set65 with the force-field parameters for the ΔaPro residue being derived manually from standard GROMOS parameters by analogy reasoning (details given in Supporting Information). All simulations were started from the X-ray structure of the aPP dimer (pdb code 1PPT) with residues 4, 6, and/or 13 changed to ΔaPro whilst retaining the native backbone conformation in the simulations of the mutants. To model pH 7 conditions all the Asp and Glu side chains and the protein C-terminus were unprotonated and His side chain was singly protonated at Nδ1. In each case, the protein conformation was solvated in a rectangular box and minimum image periodic boundary conditions were applied. The minimum solute-box wall distance was set to 1.2 nm giving between 10681 and 10797 simple point charge water molecules66. Four sodium ions were added in each case to achieve overall neutrality of the system.

For each structure, an initial equilibration scheme comprising five 20 ps simulations at temperatures of 60 K, 120 K, 180 K, 240 K and 298 K was used. During the first 80 ps of this equilibration, the solute atoms were harmonically restrained to their positions in the starting structure with force constants of 25000, 2500, 250, and 25 kJ mol−1 nm-2 respectively. Following equilibration each simulation was run at 298 K and at a constant pressure of 1 atm for 100 ns (wt aPP) or 50 ns (ΔaPro-substituted variants), the temperature and pressure being maintained using the weak coupling algorithm67, with relaxation times of τT = 0.1 ps and τp = 0.5 ps and an isothermal compressibility of 4.575 × 10−4 (kJ mol−1 nm−3)−1. Protein and solvent were separately coupled to the heat bath. The SHAKE algorithm68 was used to constrain bond lengths and the geometry of the water molecules, with a relative geometric tolerance of 10−4 allowing for an integration time step of 2 fs. The center of mass motion was removed every 1000 time steps. Non-bonded interactions were calculated using a triple-range cutoff scheme with cutoff radii of 0.8 and 1.4 nm. Interactions within 0.8 nm were evaluated every time step and intermediate range interactions were updated every fifth time step. To account for the influence of the dielectric medium outside the cutoff sphere, a reaction-field force69 with a relative dielectric permittivity ε of 61 was used70.

Analysis of the simulations was performed with the GROMOS++ suite of analysis programs62, using coordinate and energy trajectories written to disk every 5 ps. Conformational clustering was performed using the algorithm of Daura et al.71 and the backbone N, Cα, and C atoms of residues 3 to 34 in both chains. The rmsd cutoff used to determine the structures belonging to a single cluster was 0.15 nm.

Responses