STAT1 mediates the pro-inflammatory role of GBP5 in colitis

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), including Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic and relapsing inflammatory conditions primarily affecting the intestines. Evidence has emerged highlighting the presence of exaggerated responses from both the innate and adaptive immune systems in IBD1,2. However, the precise pathogenesis of IBD is unclear.

In exploring the pathomechanism of IBD, a causal inference analysis of the transcriptome network of patients with IBD identified guanylate binding protein 5 (GBP5) as a highly up-regulated marker gene in IBD and a driver molecule for disease pathogenesis3. GBP5 is required for the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in mononuclear cell line THP-1, suggesting a pro-inflammatory role4. Recently, GBP5 was identified as the top gene with altered expression in response to fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with IBD5. More strikingly, Gbp5 deficiency led to resistance for dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) induced colitis in mice5, corroborating the critical role of GBP5 in IBD pathogenesis5.

GBP5, an interferon-stimulated gene (ISG), is implicated in cell-autonomous immunity against intracellular infections. Several divergent hypothetical mechanisms have been proposed to explain its role in infectious immunity, including the indirect activation of AIM26 or NLRP3 inflammasome7 by GBP5, as well as the direct activation of NLRP3 inflammasome by GBP58.

Surprisingly, in a cell culture model free from intracellular infection, the human mononuclear cell line THP-1, we observed that GBP5 is required for the expression of numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines including IL1β4. The absence of intracellular infection and the extensive influence of GBP5 deficiency on gene expression suggest an inflammasome-independent mechanism for the pro-inflammatory role of GBP54. In pursuit of the precise role of GBP5 in IBD, the current study found that Gbp5 deficiency reduced the severity of intestinal inflammation in a DSS mouse model. We then demonstrated that Gbp5 is required for the proliferation of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs). Furthermore, we found that the GBP5-stimulated expression of cytokines required for ILC proliferation was mediated by STAT1.

Results

Gbp5 deficiency protects mice from DSS-induced colitis

Recently, with a GBP5-deficient THP-1 cell line, we observed that GBP5 is required for the expression of dozens of pro-inflammatory cytokines and related proteins, including IL1β, NLRP3, AIM2, and Caspase 14. To ascertain that this phenotype is not an off-target effect, and to confirm the requirement of GBP5 for the expression of the above affected pro-inflammatory proteins, we re-introduced GBP5 into the GBP5-/- THP-1 cells by transfection with a GBP5 expression plasmid and examined the mRNA expression of GBP5 and the pro-inflammatory proteins, in comparison with the GBP5-/- THP-1 cells transfected with the vector plasmid. Our results showed that the expression of IL1β, IL18, IL6, NMI, IFI35, and NLRP3 were increased when GBP5 expression was restored in GBP5-/- THP-1 cells (Supplementary Fig. 1). Thus, GBP5 likely plays a pivotal role in the expression of pro-inflammatory factors.

A previous study has showed that female mice with Gbp5 deficiency are more resistant to DSS-induced acute colitis than WT controls5. To confirm that result with male mice and further investigate the function of Gbp5 in intact animals, we generated Gbp5 gene knockout (Gbp5-/-) mice (Fig. 1a), with which an acute colitis model was established DSS feeding for 7 days. Male wildtype (WT) and Gbp5-/- mice untreated or treated with DSS were monitored for changes in body weight, disease activity index (DAI), colon length, and colon pathology. Upon DSS treatment, Gbp5-/- mice displayed a trend of higher body weight throughout the 7-day treatment periods, compared to the WT animals (Fig. 1b). Importantly, several measurements consistently demonstrated that Gbp5 ablation reduced the severity of DSS induced colitis with significantly lower DAI score from day 5 (Fig. 1c), longer colon length (Fig. 1d), and less inflammatory cell infiltration in the colon (Fig. 1e). These results reflected a decrease inflammation after Gbp5 ablation.

a Genotyping of the founder mice by PCR. −/−, both copies of the Gbp5 locus deleted; +/−, one copy of the Gbp5 locus deleted; and +/+, wildtype (WT). b, c Body weight and Disease Activity Index (DAI) scores of WT and Gbp5-/- mice, treated with 3% DSS for 7 days or not treated (NT). d, e Colon length and representative hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained images of colon cross-sections from WT and Gbp5-/- mice, untreated or treated with DSS. n = 5 biologically independent animals for each group. Scale bars: 100 μm (10X, left panels); and 20 μm (80X, right panels). Data are mean ± SEM. NS, not significant, Mann-Whitney U test. DSS, dextran sulfate sodium.

Gbp5 required for the expansion of ILCs

To determine the cellular distribution of GBP5 in colitis mice, inflamed colon tissues from WT mice were subjected to immunofluorescence staining for GBP5 and immune cell markers. Confocal microscopy showed that most of the F4/80+ cells expressed GBP5, rather than CD127+ and CD45R/B220+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 2). F4/80+, CD127+, and CD45R/B220+ are canonical markers for mouse macrophages, T/ILCs, and B cells9,10,11. ILCs are a crucial component of the innate immune system and are highly enriched in the intestinal mucosa12. Given the involvement of ILCs in the early stages of intestinal inflammation12,13 and their implication in IBD14,15,16,17,18,19, we examined the effect of Gbp5 deficiency on the expression of ILC-related genes, using our transcriptome dataset generated from WT and GBP5-/- THP-1, with or without stimulation by IFNγ/LPS4. We observed that, when primed with IFNγ/LPS, drivers for ILC1 (Il12b, Il15, and Il18), ILC2 (Il33) and ILC3 (Il12b, Il1b and Il23a) all exhibited decreased mRNA expression in GBP5-/- THP-1 cells compared to WT cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a).

To validate this finding, we examined the gene expression of the ILC drivers in IFNγ/LPS primed bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) isolated from Gbp5-/- and WT mice. Similarly, the driver genes for all groups of ILCs (Il12b, Il33, Il25, and Il23a) exhibited decreased mRNA expression in Gbp5-/- mouse BMDMs compared to the WT BMDMs (Supplementary Fig. 3b).

For evidence of ILC expansion at cellular level, ILC1s (CD45+Lin–RORγt–NKp46+), ILC2s (CD45+Lin–RORγt–KLRG1+), and ILC3s (CD45+Lin–RORγt+) isolated from the colons of mice exposed to DSS for 7 days and untreated mice were quantified by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 2a, b). In WT mice, the cell counts of all ILC groups were increased upon DSS treatment. However, the amplification of all ILC groups in Gbp5–/- mice was significantly suppressed (Fig. 2a). The percent representation of ILC1, ILC2 and ILC3 remained similar in the colon of Gbp5–/- mice compared to those of the WT mice (Fig. 2b). For further insight on the role of Gbp5 in ILC activation, we assessed the mRNA expression levels of ILC related genes in the colon of DSS treated mice. The deletion of Gbp5 caused a decrease in the driver cytokines for ILC1 (Il12a and Il18), ILC2 (Il33 and Il25) and ILC3 (Il12b and Il23a), and consistently in the marker proteins for ILC1 (Ifng, Klrb1c), ILC2 (Il1rl1, Klrg1) and ILC3 (Il17a, Il22) (Fig. 2c). These data indicate that Gbp5 is required for the expansion of all ILC groups in DSS mouse model of colitis.

a Counts of ILC1s, ILC2s and ILC3s in the colon of DSS-treated mice and control mice. Values are based on the total numbers of ILCs and the percent representations of each ILC. b Flow cytometry analysis of ILC1s (NKp46+RORγt–), ILC2s (KLRG1+RORγt–) and ILC3s (RORγt+) in the colons of DSS-treated mice and control mice. CD45+Lin– lymphocytes were gated out for analysis of ILCs. (Lin = CD3ε, CD45R/B220). Numbers denote percentage of cells inside the gate. c The expression levels of driver cytokines for ILCs and ILC markers in the colons of WT and Gbp5-/- mice on day 7 of DSS treatment, according to qRT-PCR analyses, normalized to that of ACTB. n = 3 biologically independent samples for each group. Data are mean ± SEM, Mann-Whitney U test.

The mRNA expression pattern of the GBP5 deficient cell mirrors that under STAT1 activation

Another outstanding observation with the transcriptome dataset of GBP5-/- THP-1 cells4 was decreased expression levels of STAT1 and its downstream effectors such as JAK2, MUC1, IRF7, and STAT2 in GBP5 deficiency (Fig. 3a). We then examined the expression levels of genes repressed by STAT1, including CCND1, MYC, CDC25A, and PPARA. Consistently, the expression levels of these genes were increased in GBP5 deficient cells compared to the WT controls (Fig. 3a). Further support for the functional association between GBP5 and STAT1 was provided by gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), showing reduced expression of JAK-STAT signaling pathway genes in GBP5-/- THP-1 cells (Fig. 3b).

a Plots are the mRNA expression data of STAT1 and STAT1 target genes from RNA sequencing-based transcriptome analysis. Wildtype and GBP5-/- THP-1 cells were treated with IFNγ (25 ng/ml) plus LPS (500 ng/ml) or mock-treated for 16 h. The list of the STAT1 target genes was from TRRUST version 2, with a few others (CCND1, MYC, and CDC25A) added according to the literature. Genes known to be stimulated and repressed by STAT1 are indicated by red and green, respectively. n = 3 biologically independent samples for each group. b Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of the entire transcriptome data of GBP5-/- cells compared to wild-type THP-1 cells. The upper panel is the enrichment score curve for JAK-STAT signaling pathway, showing the decreased expression level of relevant genes in Gbp5 deficient cells. The middle panel shows the distribution of the genes related to JAK-STAT signaling pathway. The genes were ranked according to their differential expression between wild-type and GBP5-/- cells. The lower panel is a graphical representation of the correlations between gene expression levels and the genotypes: WT or GBP5-/-. NES, normalized enrichment scores; FDR, false discovery rate.

Next, we examined the transcription levels of GBP5, STAT1, and STAT1 target genes in colonic mucosa of IBD patients and controls using a public transcriptome dataset (GSE5907120). Our analysis demonstrated higher expression levels of GBP5 and STAT1 in inflamed patient tissues compared to healthy or non-inflamed tissue (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Similarly, most STAT1-driven genes exhibited increased expression levels while genes negatively regulated by STAT1 showed lower expression levels in inflamed tissues (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Spearman’s correlation analyses confirmed a positive correlation between GBP5 expression and STAT1-driven genes (IRF1, PML and ICAM1), and a negative correlation with STAT1 repressed genes (FCGRT, FGFR3 and NR1H4) (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Additional validation with public transcriptome datasets (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b, d) supported these observations. To confirm these findings, a validation cohort including healthy controls, active CD, inactive CD and active UC patients were enrolled (Supplementary Table 1). The GBP5 and STAT1 mRNA levels in colonic mucosa were evaluated by qRT-PCR. Similarly, elevated GBP5 and STAT1 expression were observed in active CD and UC patients (Supplementary Fig. 5c). Spearman’s correlation analyses showed a positive correlation between GBP5 and STAT1 expression (Supplementary Fig. 5d). For evidence at the protein level, immunohistochemical staining was performed on consecutive colonic sections from IBD patients. The results showed similar cellular distributions and high expressions of GBP5 and STAT1 in infiltrating inflammatory cells in the lamina propria, but rarely in epithelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 6). These results lead to the hypothesis that the pro-inflammatory effect of GBP5 is mediated by STAT1.

STAT1 mediates the pro-inflammatory effect of GBP5

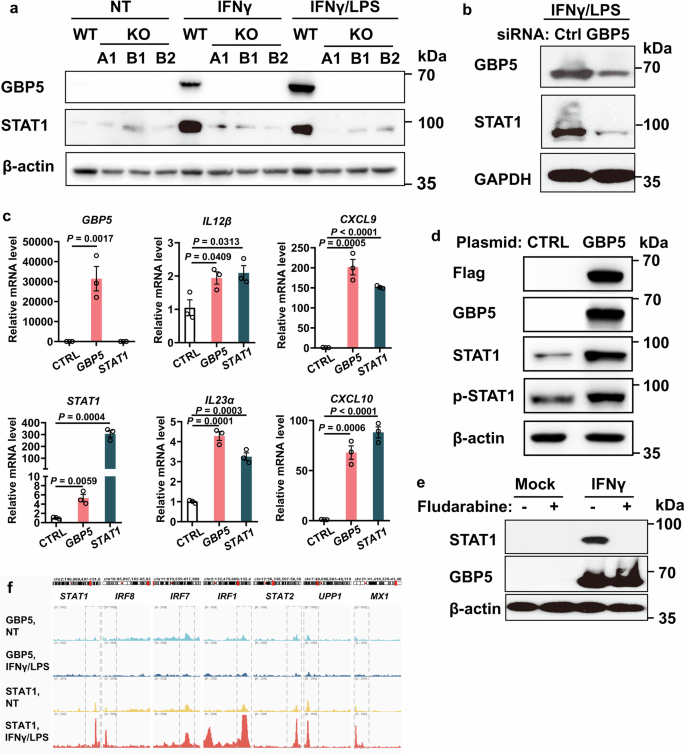

To ascertain a causal relationship between GBP5 and STAT1, we examined the effect of GBP5 deficiency on the expression of STAT1 by Western blot. Three distinct lines of GBP5-/- THP-1 cells displayed diminished STAT1 expression (Fig. 4a). Similarly, GBP5 knockdown by siRNA caused decreased STAT1 expression in Jurkat cells (Fig. 4b). Re-introduction of GBP5 into GBP5-/- THP-1 cells restored the expression of GBP5, STAT1 and STAT1-driven cytokines (Fig. 4c, d). More importantly, over-expression of STAT1 in GBP5-/- THP-1 cells also restored the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL12B and IL23A, the driver cytokines for the expansion of ILC1 and ILC3, respectively (Fig. 4c). Rescue of the inhibitory effect of GBP5 deficiency by STAT1 suggests that STAT1 mediates the pro-inflammatory role of GBP5 (Fig. 4c).

a Expression of GBP5 and STAT1 in the wildtype and GBP5-/- (three different clones A1, B1, and B2) THP-1 cells. THP-1 cells were treated with IFNγ (25 ng/ml), or IFNγ (25 ng/ml) plus LPS (500 ng/ml), or mock treated for 16 h. Cells were then harvested for Western blot analyses with anti-GBP5, anti-STAT1, and anti-β-actin antibodies, respectively. b Expression of GBP5 and STAT1 after siRNA knockdown of GBP5 in Jurkat cells. Jurkat cells were treated with GBP5 siRNA or control RNA for 48 h and subsequently stimulated with IFNγ/LPS for an additional 16 h. Cells were then harvested and subjected to Western blot analyses with anti-GBP5, anti-STAT1, and anti-GAPDH antibodies, respectively. c GBP5-/- THP-1 cells were transfected with either control (CTRL), GBP5 or STAT1 plasmid for 48 h, followed by treatment with IFNγ/LPS for 16 h. The cells were then harvested and subjected to RT-qPCR analysis. n = 3 biologically independent samples for each group. Data are mean ± SEM, Student t-test. d GBP5-/- THP-1 cells were transfected with either control (CTRL) or GBP5 plasmid for 48 h, followed by treatment with IFNγ/LPS for 16 h. Cells were then harvested and analyzed by Western blot with anti-Flag, anti-GBP5, anti-STAT1, anti-p-STAT1 (S727), and anti-β-actin antibodies, respectively. e Persistent expression of GBP5 despite the diminished expression of STAT1. THP-1 cells were treated with fludarabine (10 ng/ml) or mock-treated for 4 h, followed by IFNγ stimulation for 16 h. Cells were then harvested and analyzed by Western blot with anti-STAT1, anti-GBP5, and anti-β-actin antibodies, respectively. f UCSC genome browser tracks showing ChIP-seq of GBP5 (with or without IFNγ/LPS stimulation) and STAT1 (with or without IFNγ/LPS stimulation) bound promoter region of selected STAT1 effector genes in THP-1 cells.

On the other hand, depletion of STAT1 by fludarabine did not affect the IFNγ-induced expression of GBP5 (Fig. 4e). Thus, GBP5 is required for the induced expression of STAT1, while STAT1 is dispensable for the induced expression of GBP5.

To determine whether GBP5 directly drives the expression of pro-inflammatory proteins, CUT&Tag-seq was performed with THP-1 cells treated with IFNγ/LPS or mock-treated for 16 h using antibodies specific to GBP5 or STAT1, followed by sequencing of the bound DNA. As expected, binding of STAT1 (stimulated by IFNγ/LPS) to target genes (STAT1, IRF8, IRF7, IRF1, STAT2, UPP1, MX1) were detected with anti-STAT1. However, no significant binding site of GBP5 (stimulated by IFNγ/LPS or negative control) was detected with anti-GBP5 (Fig. 4f).

These results suggest that GBP5 is required for the induced expression of STAT1, which in turn induces the expression of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines, including those driving the expansion of ILCs.

Interaction between GBP5 and STAT1: in vitro and in vivo evidence

To explore further, we aimed to determine if GBP5 not only induces STAT1 expression but also modulates its activity. To this end, co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) was conducted on THP-1 cells, both untreated and treated with IFNγ/LPS, using anti-GBP5. The precipitated proteins were identified by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Three STAT1 peptides were detected in the precipitation from IFNγ/LPS stimulated cells, whereas they were absent from the control samples (Fig. 5a). Western blots with the co-IP samples confirmed that STAT1 was co-precipitated with GBP5 by anti-GBP5 (Fig. 5b). On the other hand, co-IP was performed with anti-STAT1 antibody. Western blot analysis indicated that GBP5 was precipitated along with STAT1 by the anti-STAT1 antibody (Fig. 5c). For molecular insight into the GBP5-STAT1 interaction, we performed a rigid protein- protein docking simulation using the protein structure information obtained from AlphaFold for GBP5 (AlphaFold_Q96PP8) and STAT1 (AlphaFold_P42224). The simulation revealed a stable interaction between GBP5 and STAT1, characterized by 26 hydrogen bonds and 10 salt bridges at their interface (Fig. 5d; Supplementary Fig. 7; Supplementary Movie 1; Supplementary Table 2).

a Identification of STAT1 in the bound fraction of anti-GBP5 immunoprecipitation by liquid chromatograph followed by tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Wildtype THP-1 cells were treated with IFNγ/LPS or mock treated for 16 h. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-GBP5. The bound fraction of the IFNγ/LPS treated sample was in-gel digested before LC-MS/MS analysis of the peptides. The collision-induced dissociation spectra of three STAT1 peptides are shown. b Western blot analyses of the total lysates (input) and bound fractions from immunoprecipitation with anti-GBP5. Lysates were prepared from wild-type THP-1 cells treated with IFNγ/LPS or mock-treated for 16 h. Blots were probed for GBP5, STAT1, and β-actin as indicated. c Western blot analyses of the total lysates (input) and bound fractions from immunoprecipitation with anti-STAT1, or IgG (control). Lysates were prepared from wild-type THP-1 cells treated with IFNγ/LPS or mock-treated for 16 h. Blots were probed for GBP5, STAT1, and β-actin as indicated. d Dock simulation for GBP5 and STAT1 interaction. The left panel represents the surface diagram of the docking model, where blue and yellow indicate GBP5 and STAT1, respectively. The right panel displays the interface of the docking model, highlighting the amino acid residues involved in the interaction.

To investigate the interaction between GBP5 and STAT1 in vivo, we first examined the cellular and subcellular distributions of these two proteins by confocal microscopy after immunofluorescence staining of the inflamed colon tissues of patients with IBD and mice with colitis. The results showed that GBP5 and STAT1 were expressed in the same cells in inflamed colon tissue both of human and mice, and that the two proteins displayed overlapping subcellular distribution (Supplementary Fig. 8a, Supplementary Fig. 2). Next, proximity ligation assay (PLA) was performed with an anti-GBP5 antibody and an anti-STAT1 antibody, which demonstrated real-time evidence of GBP5-STAT1 interaction in the inflamed colon sections of patients with IBD (Supplementary Fig. 8b). These results revealed GBP5-STAT1 interaction in vitro and in vivo.

Binding of GBP5 to STAT1 promotes the nuclear translocation of STAT1

To investigate whether GBP5 interacts with STAT1 in live cells, subcellular localization of GBP5 and STAT1 in IFNγ/LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells was visualized by confocal microscopy. As expected, GBP5 co-localized with STAT1 in THP-1 cells, both in the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 6a). More importantly, in response to IFNγ/LPS stimuli, STAT1 was translocated to the nucleus in the presence of GBP5, which was also observed in the cells of inflamed colon tissue of IBD patients (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Fig. 9).

a Immunofluorescence staining of THP-1 cells untreated or treated with IFNγ/LPS using antibodies against GBP5 and STAT1. Scale bar: 5 μm. b Subcellular fractionation analysis of GBP5 and STAT1. WT and GBP5-/- THP-1 cells were untreated or treated with IFNγ/LPS for 16 h, harvested to prepare nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, and analyzed by Western blot with antibodies against GBP5, STAT1, and p-STAT1 (S727). GAPDH and Lamin B were used as internal references. The bar plot on the right was the quantification of three independent experiments. n = 3 biologically independent experiments for each group. Data are mean ± SEM, paired student t-test. c GBP5-STAT1 proximity ligation assay with THP-1 cells untreated or treated with IFNγ/LPS. Each red spot represents an interaction. Scale bar: 2 μm. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue).

To quantitate the exte nt of GBP5 translocation and to quantitatively evaluate the effect of GBP5 deficiency on STAT1 translocation, we performed subcellular fractionation separation with WT and GBP5-/- THP-1 cells, untreated or treated with IFNγ/LPS, followed by Western blot analysis. Western blot showed that both GBP5 and STAT1 were localized in the nucleus as well as in the cytoplasm in cells treated with IFNγ/LPS (Fig. 6b). Importantly, the percent nuclear translocation of STAT1 was negligible in GBP5-/- THP-1 cells, compared to that in the WT cells (Fig. 6b).

For direct evidence of GBP5-STAT1 interaction in live THP-1 cells, PLA was performed in IFNγ/LPS stimulated cells with an anti-GBP5 antibody and an anti-STAT1 antibody, which revealed distinct spots dispersed throughout the cell indicating GBP5-STAT1 interactions in both cytosol and nucleus (Fig. 6c). These data suggest that GBP5 promotes STAT1 activity by assisting the translocation of STAT1 from cytoplasm to nucleus.

Discussion

Here, we demonstrate that GBP5 is essential for the induction of ILCs by regulating the cytokines that drive the proliferation of these innate immune cells. Furthermore, we show that the pro-inflammatory role of GBP5 is mediated through enhanced STAT1 activity. Previous studies from Luu et al.5 and our group3,4 establish GBP5 as a driver in the development of IBD. The cellular and molecular mechanisms uncovered in the present study provide compelling evidence for the essential role of GBP5 in the pathogenesis of IBD. Importantly, the cellular and molecular events identified here are suggestive of new targets for the diagnosis and treatment of IBD.

Previous research on GBP5 mainly concern infectious immunity and has demonstrated a role for GBP5 in clearing intracellular pathogens, including Francisella novicida6, Toxoplasma gondii21, influenza A virus22, HIV-1 virus23,24, respiratory syncytial virus25, Zika and measles virus26. The involvement of intracellular pathogens in the pathomechanism of IBD is a topic of ongoing debate27,28, and we cannot exclude the possibility that GBP5 is involved in the cell autonomous immunity in IBD. However, our observations with pathogen-free cell culture and specific-pathogen-free mouse model suggest that the role of GBP5 in driving intestinal inflammation can be independent of intracellular infections.

Significantly, our data have uncovered a regulatory role for GBP5 in innate immunity that is distinct from those established in models of infectious immunity. Previous studies have primarily focused on GBP5′s involvement in clearing intracellular pathogens by activating AIM2 or NLRP3 inflammasomes6,7,8. In contrast, our research using cell culture and animal models of intestinal inflammation has shown that GBP5 is essential for the stimulated expression of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines and related proteins. This indicates a more comprehensive and more potent regulation of inflammatory signaling by GBP5, surpassing the control of inflammasome activation alone. Indeed, our data suggest that GBP5 plays a pro-inflammatory role through the induction of ILCs.

Our data cannot fully exclude the possibility that the decrease in ILCs observed in DSS-treated Gbp5 KO mice was the result of the reduced inflammation. In this context, inflammation may drive the activation/expansion of ILCs, which then play a secondary role in aggravating colonic inflammation through its effector cytokines. However, a more reasonable explanation is that the activation/expansion of ILCs directly mediates the proinflammatory function of Gbp5. In the inflamed mouse colons, GBP5 was most highly expressed in F4/80+ macrophages. Using THP-1 cells, BMDMs isolated from mice and DSS mouse models, we demonstrated that Gbp5 deficiency led to decreased expression of driver cytokines for ILC1, 2, and 3, and accordingly, reduced frequencies of ILC1, 2, and 3 in the intestinal mucosa of DSS mice. As essential components of innate immunity, ILCs play a crucial role in the early immune responses and in orchestrating the subsequent adaptive immune responses in IBD pathogenesis18. Previous studies have reported the activation of ILC114,15 and ILC316,29 in patients with IBD and mouse colitis models. However, the involvement of ILC2 in IBD pathophysiology remains unclear30. Our findings highlight GBP5 as a universal regulatory factor for all groups of ILCs. This positions GBP5 as an ideal marker/target for diagnosing and intervening in IBD, as it governs the early and rapid response reactions in the inflammatory cascade of IBD, regardless of the specific ILC group involved.

In our exploration of the mechanism behind GBP5′s upregulation of driver cytokines for ILCs, we found that GBP5 promotes the activity and expression level of STAT1. Our results demonstrate that GBP5 is required for the expression of STAT1 and its effectors. Significantly, over-expression of exogenous STAT1 was able to rescue the diminished expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines due to GBP5 deficiency. After ruling out the possibility of GBP5 directly driving gene expression as a transcription factor, it became evident that STAT1 mediates the pro-inflammatory effect of GBP5.

It is noteworthy that in GBP5 deficient cells, over-expression of STAT1 restored the expression of IL12B and IL23A, which are cytokines driving the expansion of ILC1 and ILC3, respectively. Thus, STAT1 plays a significant role in mediating the induction of pro-inflammatory ILCs by GBP5. Previous studies have shown that STAT1 directly drives the transcription of IL15 and IL3331, which can stimulate the expansion of ILC1 and ILC2, respectively. However, there is no evidence available for STAT1 directly driving the transcription of other driver cytokines for ILCs. The stimulated expression of other driver cytokines for ILCs, such as IL12 and IL23, is likely indirectly regulated by STAT1. For example, as reported in other models of inflammatory diseases, STAT1 may enhance the activity of STAT332, which subsequently induces the expression of IL23A33.

On the other hand, our data suggest that GBP5 promotes STAT1 activity by facilitating the translocation of STAT1 from cytoplasm to nucleus. Relevant evidence in support of this role includes: enhanced nuclear translocation in the presence of GBP5, cellular and subcellular co-localization of GBP5 and STAT1, binding of GBP5 and STAT1 both in vitro and in vivo, stable interaction between GBP5 and STAT1 in a docking simulation, and positive correlations between the expression levels of GBP5 and STAT1, as well as between GBP5 and STAT1 effector genes, observed in cell culture and animal models, and in the colonic mucosa of patients with IBD. In support of our findings, Zhou et al. reported that GBP5 promotes the expression of several pro-inflammatory genes through enhanced NF-κB signaling pathways in macrophages34. Considering that STAT1 is a transcription factor for itself31, it is reasonable to propose that the activation of STAT1 activity by GBP5 may serve as the underlying mechanism for GBP5-induced expression of STAT1.

GBP5, a well-known ISG, is under the transcriptional regulation of STAT135,36. However, our observations indicate that GBP5 expression can still be induced even in the absence of STAT1, as shown when depleted using fludarabine. This suggests the involvement of alternative transcription factor(s) in driving GBP5 expression. Subsequently, GBP5 may enhance STAT1 activity and expression (as demonstrated in our study), which, in turn, upregulates the expression of GBP535,36, thereby activating a positive feedback loop. Thereafter, elevated STAT1 levels can drive the expression of many pro-inflammatory factors, including those cytokines known to drive the expansion of ILCs31. Subsequently, the amplification of ILCs contributes to the development of intestinal inflammation. The pathological role of STAT1 in IBD has been implicated by the increased expression and activation of STAT1 in the inflamed mucosa of both IBD patients37 and animal models38. One step further, our study suggests that STAT1 mediates the pathological role of GBP5 in intestinal inflammation. Besides STATs, IRFs are another important transcription factor family upon interferon stimulation39. A recent study showed that mice with Gbp5 deficiency exhibited increased IRF4 phosphorylation in their colonic tissue compared to WT controls5. Considering that IRF4 plays a role in the regulation STAT1 activation40, further investigation is needed to clarify the relationships among GBP5, IRF4, and STAT1.

One immediate question to be addressed in the future is the detailed mechanism for GBP5 to stimulate the STAT1 activity. More specifically, how does GBP5 facilitate the translocation of STAT1 from cytosol to nucleus? One possible mechanism is that binding to GBP5 may enhance the stability of STAT1. Another important knowledge gap is whether STAT1 is the only mediator between GBP5 and inflammatory effector cells and molecules. Bridging this knowledge gap will lead to a better understanding of the molecular pathomechanism of IBD.

In summary, we demonstrate that GBP5 promotes intestinal inflammation through the activation of pro-inflammatory ILCs. Furthermore, we show strong evidence that the pro-inflammatory effect is mediated through enhanced STAT1 activity. The fact that GBP5 regulates the early immune response steps in the colitis highlights targeting GBP5/STAT1 signal cascade as an effective strategy for the management of IBD and potentially other autoimmune diseases.

Methods

Mice

Gbp5+/- and wildtype (WT) mice on C57BL/6J background were purchased from the GemPharmatech Co., Ltd (China) and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions. Gbp5+/- mice were intercrossed to obtain biallelic Gbp5-/- mice. Genotypes were determined by PCR analysis of ear clip genomic DNA.

The PCR primers used are as follows:

F1 (Forward): 5′-CTCATTGTGCAAACAGTGGACAGC-3′

R1 (Reverse): 5′-CTTCCTTGCCAGCTTCTTAATGAAGG-3′

F2 (Forward): 5′-CTTTATGCAGTATCAGGGGAAAGGAC-3′

R2 (Reverse): 5′-CCTCCTGGAAGAGTCTTGGTCTTAGAT-3′

Representative results of PCR genotyping are included in Fig. 1a. For all experiments, male mice aged 6 to 8 weeks were used. Mice studies were carried out following the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (Approval No. IACUC-2023022201).

Cell lines

Human cell lines THP-1, Jurkat were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, ExCell Bio, Cat#FSP500) maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2. To knockdown GBP5 in Jurkat cells, a pool of two siRNAs (5′-GCCATAATCTCTTCATTCA-3′ and 5′-GCTCGGCTTTACTTAAGGA-3′) were used. The GBP5 knockout THP-1 cells were from our previous work4. Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) were isolated from WT or Gbp5-/- mice by flushing the femur and tibia with PBS. After removing red blood cells, BMDMs were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin, 1% mycoplasma removing agent, and 10 ng/ml MCSF (PeproTech, Cat#96-315-02-10) at 37 °C. On day 4, nonadherent cells were removed, and fresh BMDM medium was replenished. After 7 days, the culture medium was replaced with mouse IFNγ (NovoProtein, Cat#CM40-50, 20 ng/ml)/ Lipopolysaccharide (LPS, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#L2880, 50 ng/ml)-containing medium for an additional 24 h of incubation.

Human subjects

Surgically resected intestinal tissues and gut mucosal biopsies were collected as previously described4. Tissues were used for: IHC, as described below, or stored at −80 °C, and subsequently used for total RNA isolation. Human surgically resected intestinal tissues and gut mucosal biopsies were collected from the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University. The studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (Approval No. 2020ZSLYEC-320). All participating individuals gave written informed consent prior to sample collection and processing. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

RT-qPCR

Total RNAs were isolated from cultured cell lines, mouse tissues, and endoscopic biopsies using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Cat#15596018CN). For transiently transfected Gbp5-/- THP-1 cells, human IFNγ (NovoProtein, Cat#C014, 25 ng/ml) and LPS (500 ng/ml) were added to the culture medium at 48 h post-transfection, and cultured for an additional 16 h before extraction of total RNA. The cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using Fast Reverse Transcription kits (ESscience, Cat#RT001). RT-qPCR was performed using ABI QuantStudio 7 Flex PCR system in a 10 μL reaction system using ChamQ universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Cat#Q711-02). The mRNA expression levels of the tested genes relative to ACTB were determined using the 2-ΔΔCt or 2-ΔCt method (for analyses of ILC drivers and markers). The sequences of the RT-qPCR primers are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

DSS-induced acute colitis model

WT and Gbp5-/- mice were randomly assigned to two groups. One group received oral administration of 3% (w/v) dextran sodium sulfate (DSS, Meilunbio, Cat#MB553) dissolved in drinking water for 7 days, whereas the other group consumed regular drinking water. During the experimental period, changes in body weight, stool consistency, hematochezia were monitored daily to evaluate the effectiveness of the colitis model. Mice were sacrificed on day 7. Colon tissues of ~1 cm in length were isolated from the distal part of each colon for RT-qPCR analysis and the rest tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The disease activity index (DAI) was determined by summing the scores for weight loss, stool consistency and hematochezia described in a previous study41.

Isolation of ILCs from murine intestinal tissues and flow cytometry assay

Colons from WT and Gbp5-/- mice, whether treated with DSS or untreated, were longitudinally opened, with the contents, mesentery, and residual fat subsequently removed. Epithelial layers were removed by incubation in dissociation buffer (HBSS-/- containing 10 mM HEPES and 5 mM EDTA) at 37 °C for 15 min at 100 rpm on a shaker. Then, colons were cut into fine pieces and digested at 37 °C for 20 min in digestion buffer (HBSS+/+ supplemented with 4% FBS, 0.5 mg/ml DNase I, 0.5 mg/ml collagenase, and 1 mM HEPES). Leukocytes were isolated with 40–80% Percoll gradient (Cytiva, Cat#17089102) and subsequently washed with FACS buffer (DPBS containing 5 mM EDTA and 2% FBS). Then the cells were incubated in fixable viability dye (eBioscience, Cat#65-0863) for 30 min and then blocked with anti-CD16/32 antibody (Biolegend, Cat#101320) for an additional 30 min. Cells were then stained with surface markers (CD45, Lin, NKp46 and KLRG1) for 20 min on ice. For staining of nuclear antigens (RORγt), cells were permeabilized and fixed (eBioscience, Cat#00-5523) after staining the surface markers. We used the following antibodies: CD45-APC (1:1600, Biolegend, Cat#103115), KLRG1-PE (1:1600, Biolegend, Cat#138407), CD3ε-PerCP (1:800, Biolegend, Cat#155615,), CD45R/B220-PerCP (1:1600, Biolegend, Cat#103235), NKp46-APC (1:400, Biolegend, Cat#137607,), RORγt-Alexa FluorTM 488 (1:400, Biolegend, Cat#53-6981-82).

Analysis of transcriptomic data

The transcriptomic data for WT and GBP5-/- THP-1 cells untreated or treated with IFNγ/LPS were generated as previously described4. The two publically available datasets GSE59071 and GSE66407 were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus website (GEO). A list of STAT1 target genes were obtained from TRRUST version 2 (Transcriptional Regulatory Relationships Unraveled Sentence-based Text mining)42.

Immunohistochemistry

Human tissue sections were formalin fixed and paraffin embedded. Slides were heated to 60 °C for 1 h, followed by three 10 min washes in xylene to deparaffinize and single 10 min washes in 100%, 95%, and 75% alcohol to rehydrate. Then, the rest of the protocol was followed by the instructions of immunohistochemistry (IHC) kit (ZSGB-BIO, Cat#PV-6000), with the GBP5 (1:200, CST, Cat#67798S) and STAT1 antibodies (1:200, CST, Cat#14994S). For antigen retrieval, the slides were soaked in 10 mM sodium citrate (pH6.0), and heated to 100 °C for 15 min. Reactive cells were visualized by diaminobenzidine (DAB), and nuclei were stained with hematoxylin. IHC-stained slide images were obtained on an SQS-100 Slide Scanning System.

Immunofluorescence assay

For immunostaining of mouse colonic samples, we cut 5 μm sections of frozen tissue. For in situ immunofluorescence of THP-1 cells, Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 20 ng/ml, Meilunbio, Cat#MB5349) was pretreated for 24 h to make the cells adhered onto glass coverslips. The cells were left untreated or treated with IFNγ (25 ng/ml) plus LPS (500 ng/ml) for 16 h and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 10 min. The human tissue sections were prepared as in the IHC method. All cell samples and sections were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100. We used anti-mouse GBP5 (1:200, Abcam, Cat#ab313390), anti-mouse F4/80 (1:200, Abcam, Cat#ab6640), anti-mouse CD127/IL-7Rα (1:200, CST, Cat#47903), anti-mouse CD45R/B220 (1:200, Biolegend, Cat#103235), anti-human GBP5 (1:200, CST, Cat#67798S) and anti-mouse/human STAT1 (1:200, Proteintech, Cat#66545-1-Ig) as primary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Invitrogen, Cat#A32731), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Invitrogen, Cat#A11012), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Invitrogen, Cat#A11005), DyLight 594 AffiniPure goat anti-rat (EarthOx, Cat#E032440-01) and DyLight 488 AffiniPure goat anti-rat (EarthOx, Cat#E032240-01) as secondary antibodies. Nuclei were stained by DAPI. The images were visualized by Leica TCS-SP8 confocal microscope or a Zeiss LSM 880 confocal microscope (for scanning Z-series images).

Molecular docking analysis

The protein structure information for human GBP5 and human STAT1 was obtained from the AlphaFold protein structure database (https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/). Rigid protein-protein docking simulation was performed between GBP5 and STAT1 by GRAMM-X (http://gramm.compbio.ku.edu/). Protein surface area and interface were analyzed using PDBePISA server (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/pisa/), and visualized with Pymol (Version 2.5).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot

Total protein was extracted by RIPA lysis buffer containing protease inhibitor mixtures and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures (MedChemExpress, Cat#HY-K0010, Cat#HY-K0021, Cat#HY-K0022). For immunoprecipitation (IP), the cells were lysed by IP buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 50 mM EDTA), and the supernatants were collected by centrifugation. Quantification of protein was performed by BCA Protein Assay Kits (ThermoFisher, Cat#23225). Equal protein amounts were subjected to incubation with 2 μg of the corresponding antibodies at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with Protein A/G magnetic beads (MedChemExpress, Cat#HY-K0202) at room temperature (RT) for 4 h. Proteins bound to beads were eluted with elution buffer at 95 °C for 10 min, and subjected to LC-MS/MS after in-gel digestion. Total cell extracts or in vitro pulldown proteins were used for immunoblotting and analyzed with specific primary antibodies and horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Proteintech, Cat#SA00001-1, Cat#SA00001-2). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using the enhanced chemiluminescence reagent and BioRad chemiDoc Imaging System. The following antibodies were used for pulldown: anti-GBP5 (CST, Cat#67798S), anti-STAT1 (CST, Cat#14994S), anti-IgG (Proteintech, Cat#3000-0-AP). The following antibodies were used for Western Blot analysis: anti-GBP5 (1:2000, CST, Cat#67798S), anti-STAT1 (1:2000, CST, Cat#14994S), anti-phopho-STAT1 (1:2000, S727, CST, Cat#8826S), anti-FLAG (1:2500, Proteintech, Cat#66008-4-Ig), anti-Lamin B1 (1:2000, Proteintech, Cat#66095-1-Ig), anti-β-actin (1:5000, Proteintech, Cat#60009-1-Ig), anti-GAPDH (1:5000, Proteintech, Cat#60004-1-Ig).

ChIP-seq assay

The chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed with a CUT&Tag Assay Kit (Vazyme, Cat#TD903). In brief, THP-1 cells were untreated or treated with IFNγ/LPS for 16 h. Then cells were pre-washed and incubated with concanavalin A-coated magnetic beads. The bead-bound cells were incubated with anti-GBP5 (1:500, CST, Cat#67798S), anti-STAT1 (1:500, CST, Cat#14994S)., or normal IgG (1:500, Proteintech, Cat#3000-0-AP) for 2 h at RT. After washing, the secondary antibody was added for incubation at RT for 30 min followed by tagmentation with pG-Tn5 for 1 h at RT. The DNA fragments were then extracted, and a DNA library was constructed using the TruePrep Index Kit V2 (Vazyme, Cat#TD202). All libraries were sequenced by NovaSeq 6000.

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation assay

THP-1 cells were left untreated or treated with IFNγ/LPS for 16 h. Cells were subjected to nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction using the Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (KeyGEN, Cat#KGP150).

Proximity ligation assay (PLA)

Interactions between GBP5 and STAT1 were assessed in cultured cells and cryosections of patient tissue by in situ PLA. Detection of the amplicons was achieved using the Duolink in situ red detection kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#DUO92008) for fluorescence (THP-1 cells) or using the Duolink in situ brightfield detection kit (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat#DUO92012) for chromogenic development (tissue samples).

Statistics and reproducibility

All data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM). To assess differences or correlations, the following tests were used as appropriate: two-tailed unpaired Student t-test, two-tailed paired Student t-test, nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test, and Spearman’s correlation analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0. In the animal experiments, groups consisted of five age- and sex-matched mice that were randomly assigned. Detailed statistical methods and sample size (n) are shown in the figure legends. For all the statistical tests, P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses