Stiff, lightweight, and programmable architectured pyrolytic carbon lattices via modular assembling

Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) architectured structures, such as lattice structures made of pyrolytic carbon (PyC), hold great potential for revolutionizing engineering applications. By combining the architectural advantages and the inherent excellent properties of PyC, 3D architectured PyC structures exhibit outstanding characteristics, including a superior high strength-to-weight ratio and exceptional energy absorption capabilities1. Lattice structures, inspired by natural cellular materials, exemplify the benefits of architectured designs2,3. They offer low density, lightweight, design flexibility4,5,6, and high fracture toughness and strength relative to their weight7,8,9. These properties make them suitable for a wide range of industries, including aerospace10, marine11, and civil infrastructure12. The advent of additive manufacturing has recently facilitated the production of complex architectured structures, such as auxetic and gyroid designs, more efficiently and quickly13,14. Numerous studies have demonstrated the remarkable mechanical properties of these 3D printed lattice structures8,15. For instance, Zheng et al.8. used micro-stereolithography to fabricate various polymer lattices, including Octet-truss and Open-cell Kelvin foam. Compressive tests revealed a linear scaling relationship between stiffness and density, with specific stiffness remaining high across a broad range of densities.

Recent studies have explored the potential of lattice structures made of PyC for creating super strong, lightweight, and multifunctional materials15,16,17. For example, experimental results from Wang et al.18. investigated shell-based PyC nanolattices with a unit radial cell size of 1.6 μm in diameter, wall thickness ranging from 177 to 333 nm, and relative densities from 12.2% to 56.9%. Their study demonstrated that these nanolattices enable more efficient stress distribution, achieving an ultrahigh specific strength of up to 4.42 GPa·g−1·cm3, surpassing all previous micro/nanolattices at comparable densities. On the multifunctional aspect, a polymer lattice structure was 3D-printed using stereolithography (SLA) and coated with MnO₂ nanoflakes and nanoflowers19. After undergoing pyrolysis, the structure was transformed into a PyC lattice electrode, featuring a cubic unit cell size of 400 × 400 × 400 μm3 and cylindrical struts with a diameter of 160 μm, and relative densities from 25 to 39%, which retained over 92% efficiency even after 5000 cycles. Kudo and Bosi20 employed a two-stage heat treatment process, including pyrolyzing under vacuum pressure and then heating the printed lattice using joule-heating, to produce a PyC lattice structure microlattices with a 200 × 200 × 200 μm3 unit cell size, strut width of 60–70 µm, and relative densities of 30% and 28%. This approach yielded a specific strength of 0.47 GPa·g−1·cm3 and a specific stiffness of 14.39 GPa·g−1·cm3 at a density of 0.55 g·cm⁻³. These values are higher than any equivalent existing micro-architected materials and approach those of the strongest truss nanolattices. Moreover, Zhang et al.21 showed that their designed nano PyC lattices with a cubic unit cell size of 2 × 2 × 2 μm3, circular cross-sections with diameters ranging from 261 to 679 nm, and relative densities from 17 to 72%, reached a specific strength of 0.146 to 1.90 GPa·g−1·cm3, approaching the theoretical limit for the strength of such structures. However, PyC structures typically show brittle behaviors21,22. To overcome this issue, Surjadi et al.1. optimized the pyrolysis temperature for 3D-printed photopolymer lattices to produce partially carbonized lattices with a face-centered cubic unit cell and relative densities ranging from 5 to 30%, resulting in structures that are both strong and ductile. They demonstrated that these partially carbonized PyC lattices could absorb 100 times more energy than fully carbonized PyC lattices while retaining the same compressive strength. This new method allows the structures to absorb energy at high strains, up to 50%, without fracturing.

Despite the excellent properties of PyC lattices demonstrated in various studies, most research has focused on PyC lattices at the sub-millimeter level. However, many practical engineering applications require structures ranging from centimeter to meter sizes. The size of current PyC lattices is restricted by two main factors: the build volume of 3D printers and the tube size of the tube furnace. Moreover, it was found that the strength of PyC lattice is affected by size, with larger PyC lattices exhibiting diminished strength, making large-scale manufacturing challenging23,24,25. For example, Zhang et al. (2019b) showed that the strength of PyC micropillars decreased by 27% as the diameter increased from 4.6 to 12.7 µm25. To address these challenges and scale up PyC lattice structures while retaining their superior properties, we report an innovative approach in this paper: assembling millimeter-sized PyC lattices. Different joint mechanisms were designed and experimentally tested. The individual PyC lattice building blocks were first 3D printed using photocurable resins. Then, using an optimized heating cycle, they were pyrolyzed to a partially carbonized state. These PyC building block lattices were designed to allow for versatile, modular assembly in both in-plane and out-of-plane directions. Unlike previous studies, our experimental results show that increasing the size of the PyC lattices through assembly increases both the specific compressive modulus and strength. Here, to emphasize the novelty, although interlocking mechanisms for material assembly has been reported in the literature26,27,28, these studies primarily focus on polymer or polymer composite materials and lattices. For instance, NASA employed a modular assembly approach to create large-scale, ultralight aeroelastic structures using lattices made of polyetherimide with 20% chopped glass fiber reinforcement26. Furthermore, Zhang et al.29 achieved low-shrinkage pyrolytic nanocomposites containing carbon nanotubes and highlighted the potential for future scale-up using an assembly approach; however, this assembling was not reported in their work. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to utilize interlocking mechanisms for architectured PyC lattices. Additionally, our specific interlocking design for lattice structures has not been reported elsewhere.

To demonstrate the direct application of these joint PyC lattices, they were employed as the core of a sandwich composite structure. For comparison, specimens of a conventional sandwich composite structure were also fabricated using a traditional aramid paper honeycomb core. Quasi-static indentation experiments were performed to evaluate the performance of both types of sandwich composite structures. The results showed that the sandwich composite structure with the PyC lattice core consistently outperforms the conventional sandwich composite structure. The versatility of the assembling approach is also demonstrated through an example of curved structure. The proposed assembling approach for scaling up PyC lattices while retaining and even improving their superior properties offers a unique pathway for applying PyC structures in a range of applications, including space debris protection30 and bio-scaffold applications31.

Results and discussion

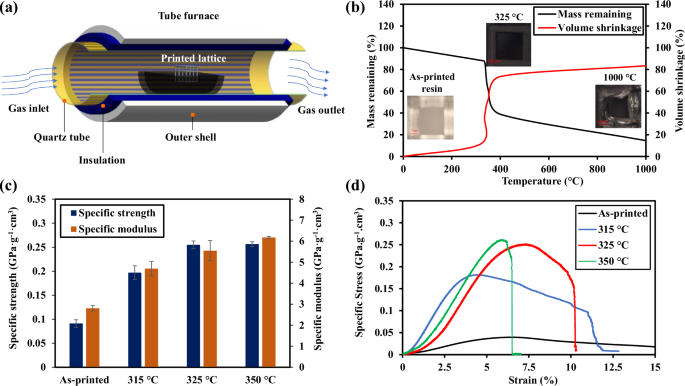

Pyrolysis for high strength and ductility

The pyrolysis process was performed under vacuum pressure and in the presence of Argon gas flow, as shown in Fig. 1a. This process aimed to capitalize on PyC’s excellent mechanical properties. To achieve this, various pyrolysis temperatures, ranging from 315 °C to 1000 °C, were investigated to determine the optimal pyrolytic transformation to achieve simultaneous high strength and ductility. The weight and volume of the PyC lattice decrease as the final pyrolysis temperature increases, as depicted in the Fig. 1b. It can be seen that the temperature range of 300–400 °C represents the most critical phase in which the polymer chains conversion to the pyrolytic carbon is occurring. In this process, only a fraction of the polymer chains are converted to the sp3 and sp2 carbon structures. The combination of sp3 and sp2 carbons with the remaining polymer chains forms hybrid or composite carbon structures that are more ductile and less distorted when compared to pristine sp3 and sp2 carbon structures1. These PyC lattices are referred to as “partially pyrolyzed” PyC lattices. This terminology and our fabrication protocol align with Surjadi et al.1, whose X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy measurements indicated a carbonization degree of 58.6% at 350 °C. The microscopic images in Fig. 1b depict the evolution of the PyC lattice morphology at elevated temperatures, highlighting four struts associated with one side of the unit cell in the lattice structure. As one can see, the struts of the lattice that are carbonized in 1000 °C are severely distorted, while those that are pyrolyzed at 325 °C have shrunk but retained the shape of the struts. It should be mentioned that the fully carbonized struts of lattices are not only distorted but also experienced bursting during the pyrolysis, making them extremely susceptible to cracking. In contrast, the structure carbonized at 325 °C maintained its integrity and shape.

a Schematic of pyrolysis process of the pre-patterned polymer lattice in a tube furnace, b remaining weight and volume shrinkage with respect to the final pyrolysis temperatures and microscopic images of four struts associated with one unit cell of the as-printed lattice and PyC lattices pyrolyzed at 325 °C and 1000 °C, respectively, c specific compressive strength and modulus of the as-printed lattice and PyC lattices pyrolyzed at 315 °C, 325 °C, and 350 °C, respectively, d the specific stress vs. strain for PyC lattices pyrolyzed at 315 °C, 325 °C, and 350 °C, respectively. Error bars in c represent standard deviation.

Figure 1c shows the specific compressive strength and modulus for an as-printed resin lattice and PyC lattice specimens pyrolyzed at different temperatures. Original data from three replicate batches are provided in Supplementary Tables 1, 2. To ensure a meaningful and consistent comparison, in this work, we used the slope of the linear region of the stress-strain curves to calculate the elastic modulus across all data. These lattices were designed such that the unit cell repeats three times in the 3D space. As one can see, first, the pyrolysis process significantly improves the specific strength and modulus of the lattice structure. Specifically, the specific strength increased by 116%, 180%, and 182% for PyC lattices pyrolyzed at 315 °C, 325 °C, and 350 °C, respectively, on average. The specific modulus increased by 68%, 98%, and 120%, respectively, on average. This is related to the fact that by increasing the temperature, more polymer chains are converted to the sp3 and sp2 carbons, thereby leading to a higher degree of carbonization and hence higher strength and modulus. However, as illustrated in Fig. 1d, an increase in the degree of carbonization adversely reduces the failure strain and the ductility. Specifically, the failure strain dropped from 12.1% to 10.3% and 6.7% when the pyrolysis temperature increases from 315 to 325 °C and 350 °C. Note that the vertical line for brittle failure is displayed only at 350 °C, as the lattice shows a higher degree of carbonization at this temperature compared to 315 °C and 325 °C. At these lower temperatures, the hybrid composite lattice demonstrates a more ductile failure mode, augmented by the buckling of the struts and a softening effect from successive layer-by-layer failure across the unit cells, progressing from top to bottom. This identified decreasing trend of the failure strain is in consistent with the findings reported in the literature1, in which it was reported that while overly pyrolyzed lattices achieve approximately 20-30% higher strength and modulus in constrast to the partially pyrolyzed PyC lattices, they exhibit significantly lower ductility, with a failure strain of 10% compared to 50%, and energy absorption is about 70-80% lower. To balance the mechanical strength and ductility of PyC, the lattices pyrolyzed at 325 °C were chosen for the next stages of this study and used as building blocks for assembling larger scale PyC lattices. These lattices exhibit higher specific strength and modulus compared to those carbonized at 315 °C, while also being more ductile than the lattices pyrolyzed at 350 °C.

Assembling PyC lattice building blocks

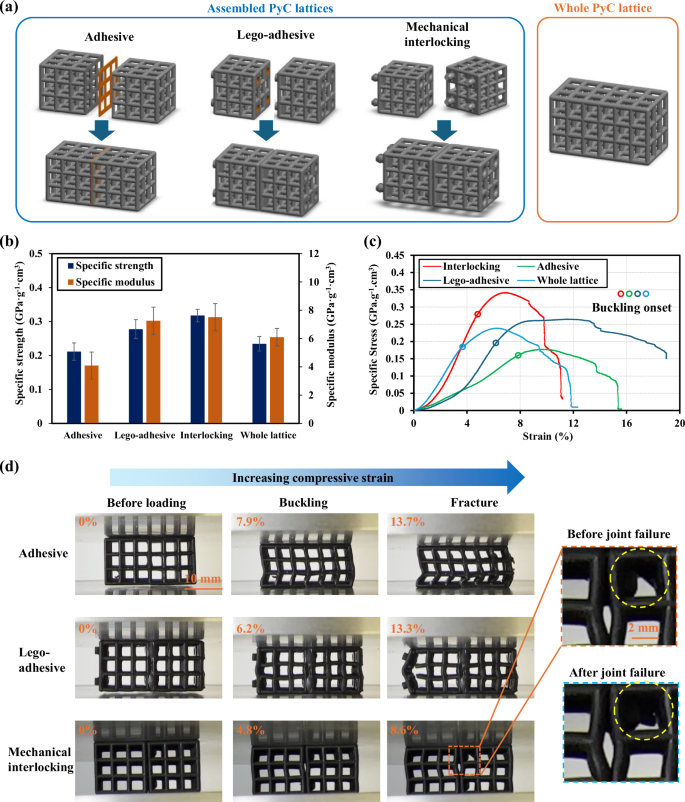

To scale up the PyC structure, we propose using millimeter-sized PyC lattices as building blocks and then assembling them into larger structures. Three different assembly mechanisms were proposed and employed: (1) adhesive, (2) Lego-adhesive, and (3) mechanical self-interlocking. Figure 2a presents schematics of these mechanisms, illustrating how individual PyC lattice building blocks are joined and how relative movement between adjacent lattices is constrained. In the adhesive method, the connecting struts were designed with half the thickness such that the adjacent connecting struts form a complete strut when joined together, utilizing aerospace-grade adhesives. The Lego-adhesive method involves using holes and cylinder connectors to join adjacent PyC lattices; each lattice is designed with holes on one side and matching cylinder connectors on the other, and adhesive is applied to ensure a tight and reliable connection, preserving the integrity of the load-bearing struts. The mechanical self-interlocking method, the simplest, fastest, and most flexible, also uses a hole-connector configuration, with the connector design inspired by expansion bolts. Once the connector is inserted into the hole, the head expands to its initial form, which is now bigger than the diameter of the hole. This expansion geometrically restricts the axial movement of the connection (see Supplementary Fig. 1). This feature enables the lattices to be readily assembled and disassembled using axial force, while nevertheless maintaining sufficient strength to endure significant out-of-plane lateral compressive stresses.

a Schematic of different joint mechanisms: adhesive, Lego-adhesive, and mechanical interlocking (with orange areas indicating where adhesive is applied), b specific strength and modulus of the assembled PyC lattices using different joint mechanisms, c specific stress vs. strain of the assembled PyC lattices using different joint mechanisms, where the hollow circles indicate the onset of buckling, d evolution of compressive deformation in the assembled PyC lattices across three stages: before loading, buckling, and fracture (with percentage numbers indicating the engineering strain and zoomed-in images on the right highlighting joint failure in the PyC lattice assembled using the mechanical interlocking method). Error bars in b represent standard deviation.

Using the above-mentioned three joint mechanisms, we fabricated larger-sized PyC lattice structures by assembling two building block lattices, each designed with the unit cell repeated three times in 3D space. With our optimized pyrolysis cycle (see details in the Methods section), adding holes and connectors to the building block lattices does not yield noticeable non-uniform shrinkage or distortion, despite the geometric asymmetry. The process involves initially heating the 3D-printed polymer lattices to 200 °C, holding for 4 hours, and then gradually increasing to the final pyrolysis temperature. This controlled heating allows volatile compounds to release gradually, preventing rapid gas buildup that could otherwise cause defects, cracks, or voids. The hold at 200 °C also facilitates initial structural stabilization through partial decomposition or cross-linking before full carbonization, ensuring uniform material breakdown. The relative density of a single PyC building block lattice is 23.74% for the adhesive configuration, 27.39% for the Lego adhesive configuration, and 28.14% for the interlocking configuration. Note that the relative densities differ between the Lego adhesive and interlocking configurations due to differences in the connector design. All struts have a diameter of 1.16 mm. The unit cell dimensions are 4.23 × 4.23 × 4.03 mm for the adhesive lattice and 4.23 × 4.23 × 4.23 mm for both the Lego adhesive and interlock lattices.

The assembled PyC lattices were then tested under compressive loading, with specific strength and modulus shown in Fig. 2b. The results for lattices assembled using the different joint methods were compared to each other and to a single, integral lattice, referred to as the “whole lattice,” which is equivalent in size to two assembled PyC building block lattices (see Fig. 2a). This whole lattice was produced by directly pyrolyzing a larger integral polymer lattice. To ensure a fair comparison, we evaluated the specific compressive properties, which were obtained by dividing the compressive properties by the density of each PyC lattice assembly, rather than relying on absolute compressive values. This approach accounts for mass differences at the interface due to adhesive layers and interlocking connectors, thereby minimizing the effect of these variations on the comparison.

The results indicate that the assembled PyC lattices using the mechanical interlocking joining mechanism exhibit the highest specific strength (0.32 ± 0.019 GPa·g−1·cm3) and modulus (7.51 ± 0.963 GPa·g−1·cm3), surpassing even those of an intact whole lattice (0.23 ± 0.021 GPa·g−1·cm3 for specific strength and 6.10 ± 0.623 GPa·g−1·cm3 for specific modulus). In contrast, the lattices assembled using the adhesive method exhibit the lowest specific strength (0.21 ± 0.025 GPa·g−1·cm3) and modulus (4.09 ± 0.955 GPa·g−1·cm3) due to the loss of structural integrity caused by the half thickness load-bearing struts associated with the connecting sides and the increased weight from the adhesive. The higher specific strength and modulus of the PyC lattice assembled using the interlocking mechanisms are also evident in Fig. 2c, which compares the specific stress versus strain for a representative batch of assembled PyC lattices and an intact whole lattice. Additionally, as shown in Fig. 2c, the PyC lattice assembled with the interlocking mechanism exhibits a failure strain of 11%, closely matching the 12% failure strain of the whole lattice.

To understand the fracture mechanisms of the joint lattices, Fig. 2d presents the evolution of deformation at various stages: before loading, buckling, and fracture. The observed deformation evolution along with the stress-strain relation as shown in Fig. 2c can determine the failure modes of the assembled joint lattices. Specifically, for PyC lattices assembled using the adhesive and Lego-adhesive methods, the strong adhesively bonded interfaces result in a global buckling pattern followed by the fracture of struts at the free edges, with a consistent pattern manifesting in both the left and right building block lattices. The global buckling is evident due to the simultaneous lateral deformations and curvature across multiple struts and building blocks. Moreover, our building block lattice is structured in a simple cubic architecture, with primarily vertical struts bearing the load and no oblique struts to facilitate bending. The stress-strain curves in Fig. 2c do not exhibit multiple peaks or load drops, which supports the absence of local buckling. Additionally, the PyC lattice assembled using the Lego-adhesive method shows a higher specific modulus (7.26 ± 0.964 GPa·g−1·cm3) compared to that assembled using only adhesive, as the Lego connectors add stiffness in the through-thickness direction, increasing the compressive modulus. The PyC lattice assembled using the mechanical interlocking method proves to be the most effective, achieving the highest specific strength and modulus. In this method, the interface between adjacent building block lattices is connected solely by mechanical interlocking, which is weaker than the interfaces in the other two methods. This mechanical interlocking mechanism constraints the axial movement and does not involve bonding of adjacent struts like the other two methods. This allows adjacent building block lattices to buckle independently, as shown in Fig. 2d. Specifically, the two adjacent building blocks display mirrored buckling patterns under compression, separating the connecting struts at the interface and leading to the fracture of the paired joint (see zoomed-in images on the right side of Fig. 2d). Compared to the deformation of the assembled PyC lattices using the other two joining methods, the mechanically interlocked PyC lattice assembly shows a unique joint fracture mechanism, further absorbing strain energy and thus improving the specific compressive strength.

Mechanical behaviors of assembled PyC lattices

Next, to investigate how increasing the size of the assembled PyC structure affects the specific strength and modulus, PyC structures were assembled using different numbers of building blocks in three directions and tested under uniaxial compression. The assembly was achieved using the mechanical interlocking method, which exhibits a clear advantage in retaining the ductility while improving the modulus and strength (see Fig. 2b). The size of the assembled PyC structure is denoted by (m, n, k), where m, n, and k represent the number of PyC building blocks in the x, y, and z directions, respectively. Assembled PyC structures with three different sizes, (2,2,1), (3,3,1), and (4,4,2), were designed, fabricated, and tested. The (2,2,1) and (3,3,1) specimens represent 2D specimens and the expansion of the dimension in the in-plane direction, while the (4,4,2) specimen represents a 3D specimen and the expansion of the dimension in the through-thickness direction. Results in Fig. 3a show a comparison of the specific strength and modulus of the assembled PyC structures with different sizes. The comparison indicates that both the specific strength and modulus increase as the size increases. Specifically, increasing the size from (1,1,1) to (2,2,1) results in a 67% increase in specific strength and a 92% increase in specific modulus. Further increasing the size from (2,2,1) to (3,3,1) increases the specific strength by 46% and the specific modulus by 16%. Finally, increasing the size from (3,3,1) to (4,4,2) leads to a 40% increase in specific strength and a 71% increase in specific modulus. This contrasts with the integral, non-assembled PyC lattice, for which it was reported in the literature that the strength reduces as the size increases1,25. The increase in specific strength and modulus with the size of the assembly demonstrates that the approach of scaling up the PyC lattices by assembling small, individual building blocks is promising and more advantageous compared to the traditional approach of directly pyrolyzing a larger-sized integral polymer lattice. It allows for an increase in the compressive strength and modulus of the structures as the size increases, while simultaneously retaining the ductility and the precise microstructure features of such lattice structures.

a The specific strength and modulus of the assembled PyC lattices as the dimension increases from (1,1,1) to (2,2,1), (3,3,1), and (4,4,2), b the specific stress vs. strain for assembled PyC lattices with increasing dimensions, c photo illustrations of two assembled PyC lattices (2,2,1) and (3,3,1) before and after compression, d the deformation and progression of damage of the (3,3,1) assembled PyC lattices during the compression test. Error bars in a represent standard deviation.

Figure 3b provides the specific stress vs. strain of the assembled PyC lattices at varying dimensions. Compared to the stress vs. strain of a single individual PyC building block lattice (1,1,1), it is observed that assembling the lattices generally increases the ductility along with its strength, indicating a significantly enhanced energy absorption capability. Compared to a single PyC building block lattice (1,1,1), the assembled lattices (2,2,1), (3,3,1), and (4,4,2) showed increases in specific energy absorption of 181%, 319%, and 137%, respectively. Specifically, fracture in the assembled lattice occurs at a strain of approximately 20% for the (2,2,1) configuration, 19% for the (3,3,1) configuration, and 10.5% for the (4,4,2) configuration. In contrast, fracture in a single building block lattice (1,1,1) occurs at a strain of 10%. Figure 3c shows the assembled PyC lattices of (3,3,1) and (2,2,1) before and after fracture. These assembled PyC lattices still hold their shape well even after fracture, with struct breakage observed mostly in the middle layer (i.e., within the second unit cell in the through-thickness direction). To gain a better understanding of why increasing the dimension of the assembled PyC lattices increases the specific strength, the evolution of the deformed shape and fracture at increasing strains is provided in Fig. 3d, corresponding to the onset of loading (Stage I), buckling (Stages II and III), and fracture (Stage IV) of the assembled PyC structure. One primary reason for the increased strength of the structure is that each PyC building block lattice under compressive loading exhibits its own buckling pattern. Specifically, the building block on the right side of the assembled PyC structure at Stage III exhibits buckling in the lateral direction (i.e., out-of-paper direction), while the other two building blocks exhibit in-plane buckling with distinct local buckling patterns. It can be concluded that the discontinuity in the buckling mode results in each lattice independently acting as an energy absorption unit, leading to enhanced strength, modulus, and ductility. Another factor contributing to the increased strength as the assembled PyC structure grows in size is the use of paired interlocking joints, which securely hold adjacent lattices together and enhance resistance to both deformation and buckling. These interconnected supports are capable of carrying a portion of the imposed loading on the structure. Thus, it can be concluded that the lightweight paired interconnecting joints significantly impact the fracture of the joint lattices.

In this study, we focused on uniaxial compression loading, where most of the load is taken by the assembled lattices themselves. The interlocking connectors enhance stability and load capacity by introducing additional fracture mechanisms, such as connector shear failure. In off-axis compression, the lattices would similarly take the majority of the load if boundaries are properly constrained, with joints adding stability. However, in flexural or tensile loading, areas not systematically explored in this study, the interlocking joints may act as weak interfaces, potentially leading to fracture at these connections, which merits further investigation.

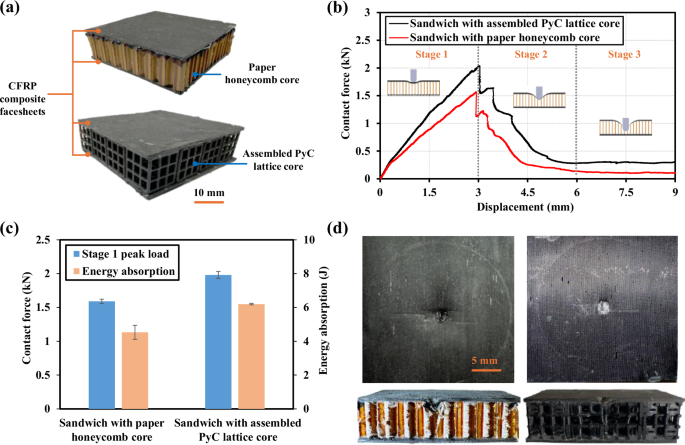

Sandwich composite structures with PyC lattice core

To demonstrate the application of the assembled PyC lattices for large scale structures, nine PyC building block lattices (with unit cells repeatedly three times each in the in-plane directions) were assembled to achieve an innovative core (4,4,1 assembly) for sandwich composite structures with top and bottom carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) matrix composite laminate face sheets. The carbon fiber composite face sheets have a cross-ply layup of [90/0/90/0] using unidirectional dry carbon fiber sheet and epoxy resin as the matrix. Then, using the aerospace graded adhesives, the core layer was bonded to the top and bottom CFRP face sheets. For comparison, a baseline sandwich composite structure with traditional aramid paper honeycomb core with the same dimensions was fabricated. Note that we selected a paper foam core as it represents one of the state-of-the-art solutions for sandwich composite structures32 and serves as a control specimen to highlight the scalability potential of our assembled PyC lattices for practical applications. The aramid paper is a synthetic paper made from aramid fibers. The relative density of the paper core is 20%, while that of the PyC lattice core is 28%. A comparison of the two specimens is shown in Fig. 4a. The two sandwich composite specimens were subjected to concentrated quasi-static indentation test following the ASTM D6264 standard33 with 1/3 scaled-down indenter size to accommodate the small dimension of our specimens. A photo of the test setup is included as Supplementary Fig. 2.

a Photographs of the two sandwich composites: one featuring an aramid paper honeycomb core and the other an assembled PyC lattice core, b load-displacement curves for both sandwich structures, c comparison of the Stage 1 peak load and energy absorption between the two sandwich structures, and d top view and cross-sectional view of the indentation damage in both sandwich structures. Error bars in c represent standard deviation.

The results in Fig. 4b show that the contact force in the sandwich composite specimen with the innovative PyC lattice core is consistently higher than that in the specimen with the traditional paper honeycomb core throughout the entire indentation process. In Stages 2 and 3, the sandwich composite with the assembled PyC lattice core maintains a contact force that is, on average, 50% higher. Figure 4c indicates that the Stage 1 peak force is 25% higher in the specimen with the PyC lattice core, with 37% more energy absorbed. It is worth noting that higher relative density typically correlates with increased energy absorption. However, the energy absorption capability of the PyC lattice in this study does not necessarily reflect its full potential, as it utilizes a basic cubic lattice architecture with primarily vertical struts bearing the load. A more sophisticated architecture could substantially enhance energy absorption with respect to its density. For instance, Surjadi et al.1. adopted a face-centered cubic architecture for partially pyrolyzed carbon lattices, significantly outperforming numerous other nano and microlattices, such as glassy carbon solid nano and microlattices and Al2O3 hollow nanolattices. Furthermore, Fig. 4d compares the indentation damage in the two sandwich composites. The top view shows surface damage, while the cross-sectional view reveals through-thickness damage. The indentation penetrates through the top CFRP composite face sheet and into the core for both sandwich structures. The damage on the surface is more localized in the composite with the PyC lattice core compared to the one with the aramid paper core, indicating higher out-of-plane stiffness from the PyC lattice core. Additionally, more visible creases appear across the indentation site in the sandwich composite with the aramid paper core, caused by the bending of the 90-degree ply of the CFRP face sheet when it contacts the hexagonal sides of the honeycomb paper core34. These results demonstrate the efficacy of the innovative PyC lattice in enhancing indentation resistance and energy absorption in sandwich composites.

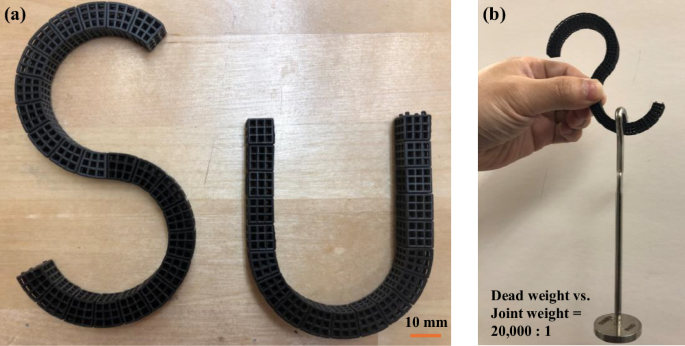

Curved PyC lattice structures

To further demonstrate the versatility of the developed modular assembling approach, PyC building blocks were used to create a centimeter-sized, curved PyC structure in the shape of “SU” (Syracuse University). Figure 5a shows the “S” letter, assembled from 23 PyC building blocks, and the “U” letter, assembled from 19 PyC building blocks. Figure 5b illustrates the load-carrying capability of the joint, with a 50-gram weight suspended in the transverse direction of the “S” PyC letter. Notably, the clamping position was carefully chosen along the midsection of the “S” structure so that its joints will be subjected to transverse loads (forces normal to the joint axis), which they are specifically designed to withstand. Clamping at other locations, such as at the top-left corner, would subject the vertical joints to a potentially disassembly scenario arising from tensile axial loads (forces parallel to the joint axis). This behavior is attributed to the mechanical interlocking joints designed for transverse shear load bearing such as compressive and indentation forces, not tensile axial forces. The total weight of the four connecting joints is 0.0025 g, resulting in a ratio of 20,000:1 between the 50-gram dead weight and the joint weight. This demonstrates a high capability of the assembly to withstand transverse shear loads at the interface. These curved PyC structures are expected to have broad potential applications in bioengineering fields, such as bone scaffolds with cylindrical shapes35. Future work aims to further optimize the interlocking design to enhance its transverse load-bearing capacity, improving its robustness and reliability for applications subjected to more complex loading conditions.

a Letter “SU” assembled using PyC lattice building blocks, b “S” PyC letter carrying a 50-gram dead weight at the interlocking joint in the transverse direction where the ratio of the dead weight to the weight of the four interlocking connectors at the interface is 20,000:1. Scale bar in a is 10 mm.

It is also worth noting that the same modular assembly approach, particularly the interlocking mechanism, can be adapted to other applications requiring various lattice geometries, such as beam, plate, or shell lattices. An example demonstrating the use of the interlocking mechanism to assemble beam lattices is provided in Supplementary Fig. 3.

The proposed modular assembling approach is more cost-effective than directly pyrolyzing large integral structures. With integral structures, localized damage or defects require discarding the entire part, wasting both material and pyrolysis energy. In contrast, with the assembling approach, only the damaged building blocks need reprinting and replacement. This modularity also allows for easy disassembly and recycling of intact blocks, further reducing costs.

Furthermore, the proposed modular assembling approach is well-suited for automation using robotic arms, with programmed picking and assembling steps to achieve high throughput, although manual assembling is used in the current work for demonstration of the idea. Additionally, multiple 3D printers can be used simultaneously to mass-produce building blocks, which can then be pyrolyzed in batches in a large industrial furnace, further reducing time and cost while improving throughput.

Conclusion

In this work, we designed stiff, lightweight, and programmable pyrolytic carbon (PyC) lattice structures by assembling individual PyC building blocks using various joining mechanisms. Before assembly, we identified the optimum temperature to achieve partially pyrolyzed PyC building block lattices with both excellent ductility and strength. Three different joint mechanisms were introduced: adhesive, Lego-adhesive, and mechanical interlocking. Among these, the mechanical interlocking joint mechanism proved to be superior to the other methods, even when compared to a single, non-assembled PyC lattice of equivalent size. Additionally, the mechanical interlocking method was demonstrated to be the easiest, fastest, and most cost-effective joint mechanism.

Our research has shown that increasing the dimension of PyC lattice structures using the assembling approach leads to an increase in both the compressive modulus and strength of the PyC structure, paving the way for their use in larger geometries. The mechanical interlocking assembling mechanism was found to further enhance the compressive modulus and strength and retain the ductility when extending the dimension in the through-thickness direction. This enhancement effect was attributed to the discontinuity in the buckling modes exhibited between neighboring lattices in the assembly. Furthermore, the direct application of the assembled PyC lattice structure was demonstrated through a sandwich composite structure that uses the assembled PyC lattice as an innovative core. This designed sandwich composite structure design was experimentally found to outperform traditional sandwich composite structures with a paper honeycomb core in terms of indentation resistance and energy absorption capability. The flexibility of the assembling approach enables the creation of PyC structures with more complex architectures, such as curved structures and scaffolds for aerospace, energy, and biomedical applications.

Note that while our study demonstrates the potential of using a modular assembly method to achieve large-scale PyC structures, it focuses primarily on the static performance of these assembled structures. Demonstrating the long-term durability and fatigue behavior of different joint mechanisms is important to practical applications and would require further investigations.

Methods

Fabrication of pyrolytic carbon lattices

The polymer lattice structure was designed using computer-aided design software (Solidworks, Dassault Systems) and then printed with a commercial SLA 3D printer (Mars 3 Pro, ELEGOO, USA) using an acrylate-based photo-curable resin (Simple Water-Washable Resin, Siraya Tech, USA). The lattices were created in a uniform configuration with unit cells repeated three times in the 3D space. After printing, the structures were rinsed with methanol and dried. To optimize the pyrolytic transformation for enhanced mechanical properties, the pyrolysis temperature was varied between 315 and 1050 °C. The as-printed polymer lattices were pre-treated in a vacuum tube furnace (GSL-1100X-NT-LD, MTI) on a quartz boat under Argon gas at 200 °C for 4 h at a heating rate of 5 °C/min to remove moisture and ensure partial carbonization. The final temperature, ranging from 315 to 1050 °C, was maintained for an additional 4 h at the same heating rate, followed by cooling to room temperature to complete the annealing process. A slow heating rate was used to ensure uniform temperature distribution throughout the structure during heating.

Fabrication of sandwich composite structure

Unidirectional carbon fabric (12 K, 139 g/m², FiberGlast, USA) and 105/206 epoxy resin (West System, USA) were used to manufacture the face sheets for the sandwich composites. Each face sheet was composed of 4 layers with a [90/0/90/0] layup configuration. The face sheets were hand-laid up and subjected to 0.1 MPa vacuum pressure for 12 h using the vacuum bagging technique to achieve partial curing and remove voids inside the laminate. Afterward, the face sheets underwent a curing process at room temperature for one week. The face sheets were then cut into 50 mm × 50 mm pieces and bonded to the honeycomb and PyC cores using a high-strength epoxy adhesive (EA 9309NA, Loctite, USA).

Mechanical tests

Uniaxial compression tests were performed using an in-house compression platen on an MTS universal testing machine, following a displacement-controlled protocol at a rate of 0.5 mm/min. The entire process was recorded with a camera to monitor the damage progression in the PyC lattices under compressive loading. For quasi-static indentation tests, a custom fixture was developed, scaled to 1/3 of the ASTM D6264 standard fixture, to accommodate the smaller specimen sizes in this study. The fixture featured an open-hole support base with a 41.7 mm diameter and a hemispherical indenter tip with a 4.3 mm diameter. These indentation tests, also conducted on the MTS universal testing machine at a constant displacement rate of 1 mm/min, were terminated before the indenter penetrated the bottom CFRP face sheet.

Responses