STING mediates increased self-renewal and lineage skewing in DNMT3A-mutated hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells

Introduction

DNA methylation plays a critical role in embryogenesis and adult tissue homeostasis by influencing gene regulation, chromatin structure and stability, gene imprinting, X chromosome inactivation, and more. In mammalian cells, DNMT3A is a de novo DNA methyltransferase that adds a methyl group to the C5 position of cytosine, producing 5-methylcytosine (5mC) on unmethylated DNA [1]. This enzyme plays a crucial role in normal development, as evidenced by Dnmt3a knockout mice, which die within one month after birth [2], and is particularly significant in hematopoietic differentiation [3]. For example, in clonal hematopoiesis (CH), a condition characterized by the clonal expansion of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the absence of hematologic disease, DNMT3A mutations are the most common genetic event, occurring in up to 40% of all CH cases [4,5,6]. While in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), mutations in DNMT3A occur at frequencies of up to 22% [7].

Dnmt3a deficiency in the mouse hematopoietic system results in increased self-renewal of HSPCs and eventually malignant transformation [3, 8]. Patient data indicate that DNMT3A mutations often serve as the ‘first-hit’ event in hematologic malignancies, requiring additional genetic alterations such as FLT3-ITDs, NPM1 mutations, and others to initiate leukemia [7, 9]. This finding aligns with the phenotypes observed in mouse models where the combined loss of Dnmt3a and expression of FLT3-ITD led to the development of AML, with a median survival time of 5-7 months. In contrast, mice with either a Dnmt3a deletion or FLT3-ITD alone survived for at least one year [10, 11]. As DNMT3A is an epigenetic regulator, mutations DNMT3A lead to the reshaping of the epigenomic landscape in HSPCs and altered gene expression. Studies on the loss of Dnmt3a in the hematopoietic system of mice have shown that hypomethylation of genes related to stemness leads to enhanced self-renewal at the expense of differentiation [8, 9, 12], even when combined with other cooperating genetic mutations [10, 11, 13, 14]. This results in a competitive advantage of Dnmt3a mutated HSCs over normal HSCs and likely increase the chance of acquiring additional oncogenic mutations in the expanded clone [15].

The transformation of DNMT3A mutation-associated CH into leukemia takes time, and the detailed mechanisms are still not fully understood. However, several laboratories have uncovered some of the effectors that are involved in this process. For example, inflammatory signaling during infections can promote CH in Dnmt3a mutants. Treatment with recombinant interferon-gamma (IFNγ) alone has been sufficient to mimic the effects of infection on Dnmt3a mutation-associated CH [16]. This finding aligns with cohort analyses of patients with ulcerative colitis, an autoimmune disease characterized by elevated levels of IFNγ, where there is notably a positive selection of clones harboring DNMT3A mutations [17]. Additionally, epidemiological studies have demonstrated that the development of CH is associated with smoking and conditions related to chronic lung disease [18]. Meanwhile, murine models have shown that cells with DNMT3A mutations gain a selective advantage in the fatty bone marrow (BM) environment. This advantage may be mediated by the release of IL-6 from both BM fluid and BM-derived adipocytes [19]. Consequently, environmental selection pressures are considered to play a significant role in the emergence of CH.

In this study, we demonstrated that loss of Sting significantly inhibits the expansion of HSPCs with Dnmt3a deficiency. Mechanistically, the deletion of Dnmt3a in HSPCs led to the hypomethylation and activation of endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) in the genome. The RNA from these ERVs was reverse transcribed into cDNA, which activated the STING pathway and triggered endogenous inflammatory responses. Both inhibition of STING and blocking reverse transcriptase with small molecules effectively reduced the enhanced repopulating capability of Dnmt3a-deficient HSPCs in vitro. Furthermore, targeting STING in a Dnmt3a-deficient murine model of AML and in a DNMT3A-mutated PDX model inhibited disease progression. Therefore, our findings propose a novel mechanism by which Dnmt3a deficiency induces intrinsic inflammation in the hematopoietic system and disrupts HSPC homeostasis through the activation of the STING pathway. Moreover, this suggests that targeting STING could be a potential strategy to prevent the development of hematopoietic malignancies in patients with DNMT3A mutations.

Results

Despite the role of extrinsic stimulus in promoting the development of hematopoietic diseases associated with DNMT3A mutations, an intriguing question remains: are there any intrinsic factors in DNMT3A mutated cells required for this process? To address this question, we initiated our study by performing a transcriptome analysis to examine the differences in gene expression between Dnmt3af/f, Mx1-Cre (hereafter named Dnmt3a-KO) and wild type (WT) HSPCs (Supplementary Fig. 1A, B).

Activated STING pathway mediates intrinsic inflammatory response in Dnmt3a-deficient HSPCs

Gene ontology (GO) analysis revealed that mitosis-related genes were the most upregulated in Dnmt3a-KO HSCs. In contrast, in the common myeloid progenitor (CMP), granulocyte/monocyte progenitor (GMP), and common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) cells, there was a significant enrichment of pathways related to inflammatory responses in the Dnmt3a-KO cells (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Furthermore, the heatmap illustrating distinctly upregulated inflammatory-related genes in Dnmt3a-KO cells compared to WT cells (Supplementary Fig. 1D), confirmed that the inflammatory responses were mainly contributed by progenitor cell populations. We validated these results through quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) assays to measure the expression levels of inflammatory cytokines in Dnmt3a-KO and WT c-Kit+ cells. Key inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, ISG15, and CXCL10, were significantly elevated in Dnmt3a-KO cells compared to WT cells (Supplementary Fig. 1E). We also measured the secreted levels of cytokines such as CXCL10, S100A9, and IFNβ using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). A significant increase in these cytokines was observed in the peripheral blood (PB) of Dnmt3a-KO mice compared to WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 1F). Together, these data suggest that Dnmt3a deficiency triggers an intrinsic inflammatory response in mouse BM progenitor cells.

Recently, we have demonstrated that STING plays a crucial role in the expansion of clones with mutations in TET2—a dioxygenase that converts 5-methylcytosine to 5-hydroxymethylcytosine—in a murine model of CH [20]. Given the similar phenotypes observed in the murine hematopoietic system with deficiencies in either Dnmt3a or Tet2, such as increased BM inflammatory signals and skewed differentiation [13], we hypothesize that the activated STING pathway also acts as an intrinsic factor inducing the inflammatory responses and mediating the development of hematopoietic disorders associated with Dnmt3a deficiency. We first measured the level of cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate (cGAMP), a secondary messenger that activates STING [21], in both WT and Dnmt3a-KO BM cells. As a comparison, we measured cGAMP levels in Tet2-KO bone marrow (BM) cells, which served as a positive control [20]. The Dnmt3a-KO BM cells exhibited approximately 4 fmol of cGAMP per 10⁷ cells, while Tet2-KO BM cells showed around 3 fmol per 10⁷ cells. In contrast, no signal was detected in the WT BM (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Loss of Dnmt3a increased the self-renewal ability of Lineage–c-Kit+Sca-1+ (LSK) cells and enhanced their repopulating capacity in the colony-forming unit (CFU) assay (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Furthermore, inhibition of STING with the small molecule C-176 [22] effectively reduced the colony-forming capability of Dnmt3a-KO cells at the third replating (Supplementary Fig. 2B). To genetically investigate the role of STING in hematopoietic disorders associated with Dnmt3a deficiency, we utilized Dnmt3af/f, Sting−/−, Mx1-Cre mice (hereafter named Dnmt3a; Sting-DKO) to explore the impact of Sting loss on the hematopoietic phenotype mediated by Dnmt3a deficiency (Fig. 1A). Transcriptome analysis revealed that loss of Sting effectively reduced the expression of inflammatory genes in Dnmt3a-deficient c-Kit+ cells (Supplementary Fig. 2C). Furthermore, the downstream pathways of STING, such as the type-I interferon response and cytokine-related signaling pathways, were also significantly diminished, as evidenced by GO analysis data between Dnmt3a; Sting-DKO and Dnmt3a-KO samples (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the cell-intrinsic inflammatory responses in Dnmt3a-KO HSPCs were dependent on the activation of the STING pathway.

A Schematic of the strategy used to generate Dnmt3a; Sting-DKO mice. The phenotypes of these mice were analyzed 16 weeks after poly(I:C) injection. B Deletion of Sting reduced the repopulating capacity of Dnmt3a-deficient LSK cells in CFU assays. LSK cells from different mice were sorted by FACS, and the number of CFUs was counted 7 days after plating. IFNβ was used at a concentration of 1 U/ml. C Loss of Sting suppressed the increased self-renewal of Dnmt3a-deficient LSK cells in vivo (n = 5). D The proportions of myeloid and lymphoid cells in peripheral blood were measured by FACS (n = 5). E Deletion of Sting specifically reduced the proliferation of Dnmt3a-KO HSPCs. The HSPCs were stained with an antibody against Ki67 and analyzed by FACS (n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m., with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, ****P < 0.0001, and “ns” not significant.

STING is involved in the Dnmt3a deficiency-induced CH

Similar to the treatment with the inhibitor, deletion of Sting significantly inhibited the colony-forming capability of Dnmt3a-deficient cells at the fourth replating in the CFU assay (Fig. 1B). In contrast, IFNβ, a cytokine typically induced by the activated STING pathway, significantly enhanced the repopulating capacity of Dnmt3a; Sting-DKO cells (Fig. 1B). This suggests that the increased repopulating capacity of Dnmt3a-deficient LSK cells requires the Sting-dependent inflammatory response. We then evaluated the impact of deleting Sting on hematopoietic differentiation in Dnmt3a-KO mice. To avoid aging-induced inflammatory responses, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) signaling [23], and the increased risk of acquiring other genetic lesions mediated by Dnmt3a deficiency, we conducted the analysis when the mice were 24 weeks old, with Dnmt3a knockout occurring after 8 weeks. Loss of Dnmt3a led to a 2-fold increase in the population of LSK cells compared to WT or Sting-KO mice, while Dnmt3a; Sting-DKO mice showed a comparable population of LSK cells to that of WT mice (Fig. 1C). The populations of downstream hematopoietic lineage cells showed no differences among the four genotypes (Fig. 1D), suggesting that the effect of Dnmt3a deficiency was limited to HSPCs at this time point. To verify this, we performed Ki67 staining to assess the proliferation index of HSPCs. The proportions of Ki67+ cells in Dnmt3a-KO HSPCs, including LSK cells, long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs), and short-term HSCs (ST-HSCs), were twice as high as those in Dnmt3a; Sting-DKO, WT, and Sting-KO cells (Fig. 1E). This suggests that the increased proliferation of HSPCs due to Dnmt3a deficiency requires STING.

To assess the cell intrinsic effects of deleting STING in promoting Dnmt3a deficiency-mediated CH, we conducted transplantation assays (Fig. 2A). 20 weeks post-transplantation, recipients with Dnmt3a-KO BM cells exhibited a 2-fold increase in spleen weight compared to recipients transplanted with WT, Sting-KO, or Dnmt3a; Sting-DKO BM cells, with the latter three showing comparable spleen weights (Fig. 2B). Additionally, the loss of Dnmt3a significantly increased the proportion of myeloid cells in the peripheral blood during the assay duration, while deletion of Sting in the context of Dnmt3a deficiency alleviated myeloid cell expansion in the recipients with comparable levels to those in WT and Sting-KO recipients (Fig. 2C, D). We next examined the HSPC populations in the BM of the different recipient mice. Consistent with previous work, deletion of Dnmt3a resulted in an expansion of the stem cell pool [3], as evidenced by increased populations of LSK cells, ST-HSCs, and LT-HSCs when compared with WT recipients. However, these expansions were significantly mitigated when combined with the deletion of Sting (Fig. 2E). The populations of LSK cells and LT-HSCs in recipients with Dnmt3a; Sting-DKO BM were comparable to those from WT recipients. Only a slight increase in ST-HSCs was observed in the Dnmt3a; Sting-DKO recipients compared to WT recipients, whereas deletion of Dnmt3a alone resulted in a 3-fold increase in this cell population (Fig. 2E). We also examined the populations of lineage progenitor cells in these mice and found a significant increase in GMP cells in Dnmt3a-KO recipients. Similarly, this effect was reversed by the deletion of Sting (Fig. 2E, bottom panel).

A Diagram of the whole bone marrow transplantation assay. B Loss of Sting alleviated the splenomegaly in recipients of Dnmt3a-deficient donor bone marrow. The weight of spleens in recipient mice was measured 20 weeks after transplantation. Quantitative data are shown on the right (n = 8). C The plot graph shows the frequency of myeloid cells in the peripheral blood of recipient mice over the course of the transplantation assay (n = 11). D Deletion of Sting inhibited the myeloid differentiation bias mediated by Dnmt3a deficiency. The proportions of myeloid and lymphoid cells in peripheral blood were measured by FACS 20 weeks post-transplantation (n = 8). E Deletion of Sting restrained the self-renewal ability of Dnmt3a-deficient HSPCs. The proportions of LSK cells, LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs were measured by FACS. Gating plots are shown on the left, and quantitative data are shown on the right (n = 8). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m., with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005, ****P < 0.0001, and “ns” not significant.

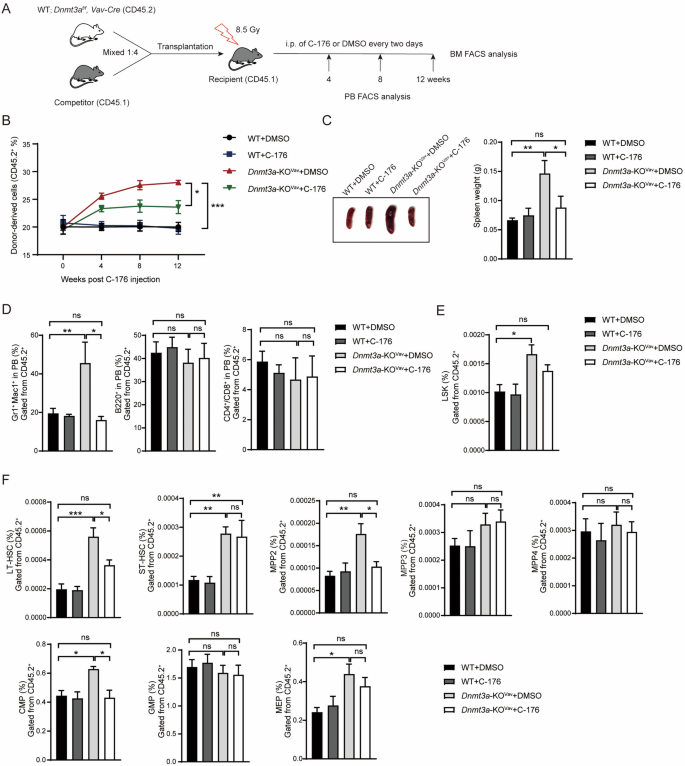

One hallmark of CH is the increased self-renewal activity of HSCs, which leads to an expansion of lineage cells in the hematopoietic system when competing with WT HSCs. To further validate the role of STING in Dnmt3a-associated CH, we conducted a competitive transplantation assay (Fig. 3A). We generated Vav-Cre mediated Dnmt3a conditional knockout mice to avoid the acute inflammatory response associated with Mx1-Cre induction in this assay (hereafter named Dnmt3a-KOVav). To explore the therapeutic potential of targeting STING in vivo, we employed the STING inhibitor C-176. Consistent with data from the whole BM transplantation assay, Dnmt3a-KOVav cells in recipients treated with DMSO displayed a significant competitive advantage in the PB, and recipients had enlarged spleens compared to WT recipients. In contrast, inhibition of STING with C-176 reduced the CD45.2 population to 25% and halved the spleen weight compared to Dnmt3a-KOVav recipients treated with DMSO (Fig. 3B, C).Twelve weeks post-transplantation, the myeloid cell population in the Dnmt3a-KOVav recipients in the DMSO group was 3-fold higher than those in the WT or the Dnmt3a-KOVav recipients treated with C-176, and C-176 injection showed no effects on T/B cell differentiation in either the WT or Dnmt3a-KOVav groups (Fig. 3D). The increased populations of LSK cells and LT-HSCs in Dnmt3a-KOVav cell recipients also returned to levels comparable to WT recipients upon inhibition of STING (Fig. 3E, F). Moreover, the loss of Dnmt3a specifically resulted in the expansion of multipotent progenitor cell 2 (MPP2) and CMP cells, while inhibition of STING with C-176 mitigated this effect. Recipients with Dnmt3a-KOVav cells exhibited similar populations of MPP3, MPP4, and GMP cells compared to WT controls and showed an increase in MEP cells, which was not significantly reduced by the inhibition of STING, potentially due to the time constraints of this assay (Fig. 3F). Taken together, these data suggest that the activation of STING plays a crucial role in mediating the development of Dnmt3a-associated CH. Furthermore, targeting STING is an effective way to prevent a series of hematopoietic disorders induced by Dnmt3a deficiency in vivo.

A Diagram of competitive transplantation assay. B Injection of the STING inhibitor C-176 impaired the competitive advantage of Dnmt3a-deficient donors over the course of the competitive assay (n = 8). C Inhibition of STING alleviated the splenomegaly mediated by Dnmt3a deficiency (n = 5). D The bar graph shows the proportions of myeloid and lymphoid cells in the recipients (n = 5). E C-176 treatment reduced the proportion of Dnmt3a-deficient LSK cells in the recipients (n = 5). F The bar graph shows the frequencies of LT-HSCs, ST-HSCs, CMPs, GMPs, MEPs and MPP2/3/4 across different groups of recipient mice (n = 5). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m., with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005 and “ns” not significant.

Hypomethylation of ERVs in the genome leads to the activation of STING in Dnmt3a-KO HSPCs

We next investigated how the STING pathway was activated in Dnmt3a-KOVav HSPCs. One possible mechanism is DNA damage, which could cause increase micronuclei (MN) formation and the releasement of genomic DNA into the cytoplasm. To test this hypothesis, we assessed the DNA damage level in WT and Dnmt3a-KOVav BM cells. There were no detectable γH2AX signals in either Dnmt3a-deficient c-Kit+ or c-Kit– cells (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Additionally, Dnmt3a-KOVav Lineage–c-Kit+ (LK) cells showed no differences from WT LK cells in the comet assay (Supplementary Fig. 3B), which is commonly used to measure overall DNA damage levels. We also counted the number of MN in both WT and Dnmt3a-KOVav LSK cells and observed no significant changes between the two cell populations (Supplementary Fig. 3C). These findings suggest that loss of Dnmt3a does not trigger an autonomous DNA damage response in HSPCs. Recently, a study reported that mutations in DNMT3A result in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) release and activation of the STING pathway in macrophages [24]. We speculated that this mechanism might also operate in HSPCs. Using the same approach, we evaluated mtDNA release in Dnmt3a-KOVav c-Kit+ cells. However, we observed no increase in mtDNA levels in Dnmt3a-KOVav c-Kit+ cells compared to WT cells (Supplementary Fig. 3D).

The reverse-transcribed cDNA of ERVs acts as another stimulus of the cGAS-STING pathway [25]. To explore this possibility, we first examined the expression of several transposable elements in Dnmt3a-KO and WT HSPC lineages. Specifically, we observed that the expression of ERVs, which belong to the group of long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons [26], was upregulated in Dnmt3a-KO HSPCs (Fig. 4A). Typically, the expression of ERVs is silenced by host surveillance mechanisms, such as DNA methylation [27]. We quantified the level of methylated cytosine in Dnmt3a-KO c-Kit+ cells using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS). Indeed, the total methylated cytosine level, including hydroxy-methyl cytosine levels in the genome of Dnmt3a-KOVav c-Kit+ cells was significantly reduced compared to WT cells (Supplementary Fig. 4A). We then analyzed the whole-genome bisulfite sequencing data of HSCs from previously published data [13, 28], finding that the average methylation level of ERV genic regions was significantly reduced in Dnmt3a-KO HSCs (Fig. 4B).

A Pie charts display the percentages of upregulated repetitive elements in each class (top), and a heatmap shows the relative expression levels of the top 7 upregulated repetitive elements (bottom) across different Dnmt3a knockout HSPC lineages. B Deletion of Dnmt3a leads to hypomethylation of ERVs. The profile of average CpG methylation levels is displayed across regions including ERVs and their 2-kb flanking areas. The methylation levels of various ERV subfamilies are illustrated at the bottom. C The upregulation of ERVs in Dnmt3a-deficient c-Kit+ cells was measured using bulk RNA-seq (left) and the specific transcripts (right, top panel) and cDNA (right, bottom panel) of ERVs in c-Kit+ cells were quantified using q-PCR. A scatter plot illustrates the differentially expressed genes (circles) and transposable elements (triangles) between Dnmt3a-KOVav and WT c-Kit+ cells, with log2(fold change) >1 and P < 0.05 (n = 3). D Dnmt3a deficiency results in the hypomethylation of genic ERV loci in c-Kit+ cells. E FACS analysis showing the populations of specific cell types in the bone marrow of RTi-treated recipient mice (n = 5). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m., with **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005 and “ns” not significant.

To explore the overall expression profiles of ERVs and genes, we analyzed our RNA-seq data performed with c-Kit+ cells from Dnmt3a-KOVav and WT mice. We identified several subsets of ERVs, such ERV1 and ERVK, that were upregulated in Dnmt3a-KOVav c-Kit+ cells and confirmed the upregulation of various ERVs in c-Kit+ cells, both in the mRNA level and in the cDNA level by q-PCR (Fig. 4C). And this upregulation of ERVs‘ transcribes was also detected in the Dnmt3a-KOVav LSK cells (Supplementary Fig. 4B). Additionally, the genic methylation levels of the upregulated ERVs, such as MMVL30, MMLV, and MuSD, were also reduced in Dnmt3a-KOVav c-Kit+ cells (Fig. 4D). To further validate the link between genome hypomethylation, ERV expression, and inflammation induction, we treated WT c-Kit+ cells with decitabine, a hypomethylation agent. As expected, decitabine treatment induced the upregulation of similar subsets of ERVs as observed in Dnmt3a-KOVav cells and significantly induced inflammatory cytokines (Supplementary Fig. 4C). The hypomethylation of the genome and ERV loci in decitabine-treated c-Kit+ cells was confirmed through LC-MS and bisulfite sequencing (Supplementary Fig. 4D). Additionally, as a biomarker of STING pathway activation, the phosphorylation of TBK1 and STING was observed in the decitabine-treated cells (Supplementary Fig. 4E). Collectively, these data suggesting that ERV activation was due to the hypomethylation.

The accumulation of ERV transcripts in the cytoplasm can directly activate the viral RNA-sensing pathway and trigger downstream inflammatory responses [27]. To address this, we silenced the expression of Mavs [29], a key adaptor mediating the RNA innate immunity response, in Dnmt3a-KOVav c-Kit+ cells and conducted a serial CFU assay to test the repopulating capacity of these cells. The knockdown of Mavs showed no inhibitory effects on the repopulating capacity of Dnmt3a-KOVav cells (Supplementary Fig. 4F), suggesting that the viral RNA-sensing pathway is not responsible for the phenotypes associated with Dnmt3a deficiency. However, when we used a reverse transcriptase inhibitor to prevent the synthesis of ERV cDNA in Dnmt3a-KOVav cells, the repopulating capacity of these cells was significantly impaired (Supplementary Fig. 4G). This finding is consistent with the previous reports that reverse-transcribed ERV cDNA acts as an inducer of the STING pathway [25, 30, 31]. We next evaluated the effects of RTi treatment in vivo. Recipient mice transplanted with WT or Dnmt3a-KOVav BM cells were administered RTi by oral gavage every other day for one month. This treatment resulted in a significant increase in the LT-HSC population in Dnmt3a-KOVav recipients compared to WT recipients. However, the ST-HSC population in DMSO-treated Dnmt3a-KOVav recipients was four times higher than that in both WT recipients and RTi-treated Dnmt3a-KOVav recipients (Fig. 4E). For progenitor cells, RTi treatment reduced the expansion of CMP and CLP populations in Dnmt3a-KOVav recipients, bringing them to levels comparable to those observed in WT recipients. Additionally, a slight increase in the proportion of MEPs was noted in RTi-treated Dnmt3a-KOVav recipients compared to the DMSO-treated group (Fig. 4E). Collectively, these results indicate that Dnmt3a deficiency results in the hypomethylation of ERV genic loci, and the reverse-transcribed cDNA of ERVs triggers the activation of the cGAS-STING pathway in Dnmt3a-KO HSPCs, ultimately driving lineage differentiation bias in mice.

Inhibiting STING delays the progression of leukemia associated with DNMT3A mutations

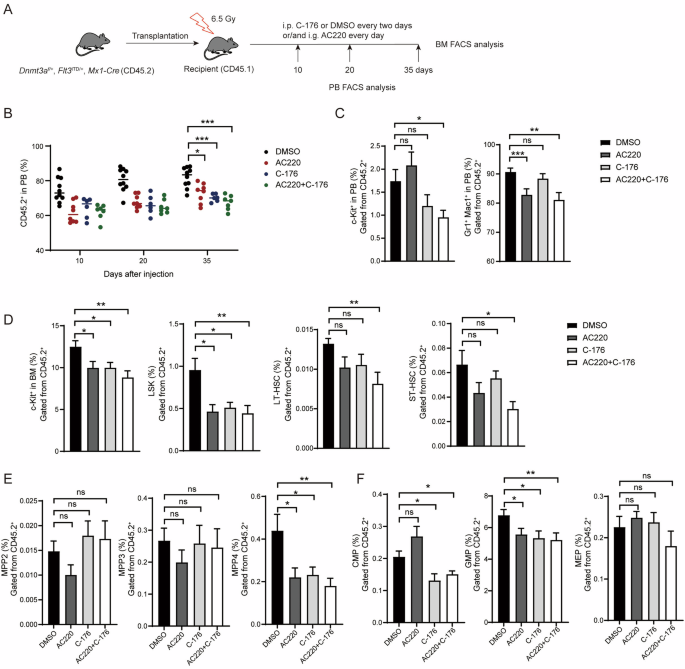

To assess whether STING can be targeted to prevent the evolution of leukemia, we generated a transgenic mouse model, Dnmt3af/+, FLT3ITD/+, Mx1-Cre, to replicate a common mutation combination seen in AML patients. To validate the effects of targeting STING in this model, we used AC220, an FDA-approved drug currently used to treat leukemia with FLT3-ITD rearrangement, as a benchmark for evaluation (Fig. 5A). In the transplantation models, recipients treated with AC220, C-176, or a combination of both exhibited significant reductions in the populations of CD45.2+ cells in the PB during the assay period (Fig. 5B). Inhibition of STING decreased the proportion of c-Kit+ cells in the PB, whereas AC220 alone had no effect on this parameter. Interestingly, the pattern of inhibition was reversed for the proportions of myeloid cells, with AC220 showing significant inhibitory effects, whereas C-176 had no impact on these cells. Moreover, the combination of these two agents demonstrated a synergistic effect, reducing the expansion of both c-Kit+ and myeloid cells in the PB by about 50% and 10%, respectively, compared to DMSO (Fig. 5C). In the BM, C-176 and AC220 showed comparable reductions in the proportions of c-Kit+ cells, LSK cells, and LT-HSCs, and neither had any effect on the population of ST-HSCs. The combination of these two drugs exhibited a synergistic effect on these cell populations, especially on ST-HSCs, showing a nearly 60% decrease compared to DMSO and a 40% decrease compared to either C-176 or AC220 alone (Fig. 5D). Neither drug had an effect on the populations of MPP2 and MPP3, yet they both demonstrated a 50% inhibition efficiency on the proportion of MPP4 (Fig. 5E). For progenitor cells, targeting STING yielded better inhibitory effects compared to AC220; the proportion of CMP cells was reduced by about 30% with STING targeting, but increased when treated with AC220. Both drugs reduced the population of GMP cells, and a cooperative effect was observed when they were used in combination (Fig. 5F). Collectively, these data indicate that the primary effect of targeting STING appears to be on the expansion of HSPCs rather than on the proliferation of leukemia blasts.

A Diagram of comparing the biological activity of C-176 and FLT3 inhibitor AC220. B Injection of either C-176 or AC220 inhibited the myeloid differentiation bias of Dnmt3a-deficient leukemia cells over the course of the transplantation assay (n = 9). C Inhibition of STING restrained the expansion of naïve hematopoietic cells in the peripheral blood of recipient mice (n = 8). D C-176 and AC220 showed a combined effect in inhibiting the expansion of Dnmt3a+/−; Flt3ITD/+ leukemia stem cells (n = 8). E C-176 and AC220 specifically inhibited the expansion of MPP4 cells (n = 8). F C-176 and AC220 treatment reduced the proportions of CMP and GMP cells in Dnmt3a+/−; Flt3ITD/+ mice (n = 8). Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m., with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005 and “ns” not significant.

We further assessed the effects of targeting STING on a patient sample with DNMT3A R882H and FLT3-ITD mutations. Inhibition of STING effectively restricted the proliferation of these leukemia cells in culture, showing a comparable inhibitory effect to AC220 treatment, while both chemicals showing no effects on the proliferation cord blood CD34+ cells (Fig. 6A). We then used this patient sample to establish a patient-derived xenograft (PDX) model in NOD/SCID/γ-chain knockout (NSG) mice, to evaluate the in vivo effects of STING inhibition. Treatment with H-151, a STING inhibitor which targets human STING, led to a threefold reduction in the expansion of human leukemia cells with DNMT3A mutation in the PB during the transplantation assays (Fig. 6B). Six weeks after initiating H-151 treatment, the proportion of leukemia cells in the PB decreased by fourfold compared to the DMSO group, while no significant changes were observed in the proportion of immature myeloid cells between the H-151 and DMSO groups (Fig. 6C). In the spleen and bone marrow, H-151 treatment reduced the proportion of leukemia stem cells threefold compared to the DMSO group, with no effect on the population of blast cells (Fig. 6D, E). These results further underscore that inhibiting STING primarily delays leukemia development by restraining the expansion of stem cells. Furthermore, H-151 treatment significantly extended the survival of mice harboring DNMT3A-mutated leukemia cells. In contrast, no increase in lifespan was observed in mice with DNMT3A wild-type leukemia cells treated with H-151. (Fig. 6F). Collectively, these findings suggest that STING is a viable therapeutic target in DNMT3A-mutated hematopoietic disorders.

A The effects of H-151 and AC220 treatments on patient-derived leukemia cells (left) and cord blood CD34+ cells (right) were evaluated in vitro using the CCK8 assay. B Inhibition of STING restrains the expansion of DNMT3A-mutated leukemia cells in NSG mice (n = 3 biological replicates). The DNMT3A-mutated patient sample harbors DNMT3A R882H and FLT3-ITD mutations, whereas the DNMT3A-WT sample carries CEBPA c.295_300del and TP53 P72R homozygous mutations. C Bar graphs display the proportions of human leukemia cells (hCD45+) and immature myeloid cells (hCD45+hCD34–hCD33+) (n = 3 biological replicates). Targeting STING diminishes the proportions of leukemia stem cells in the spleen (D) and bone marrow (E) of recipient mice. The proportions of human leukemia cells, blast cells (hCD45+hCD34+hCD38+), and leukemia stem cells (hCD45+hCD34+hCD38–) were analyzed via FACS (n = 3 biological replicates). F Survival analysis of recipient mice treated with DMSO or H-151, presented as a Kaplan–Meier curve (n = 3 with DMSO, 6 with H-151). Statistical significance was assessed by t-test (A–E). Data are mean ± s.e.m., *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Discussion

As a major driver mutation in CH and hematopoietic malignancies, DNMT3A mutations contribute to nearly 40% of genetic events in these diseases. Therefore, identifying the factors and pathways involved in the development of hematopoietic disorders associated with DNMT3A mutations is crucial for developing clinical strategies to improve patient outcomes. In this study, we demonstrated that Dnmt3a-deficient HSPCs exhibit autonomously activated STING pathways and chronic inflammation. This inflammatory state promotes the expansion and skewed differentiation of HSPC populations associated with Dnmt3a deficiency. Mechanistically, the STING pathway in Dnmt3a-deficient HSPCs is activated by the induction of ERVs, which become hypomethylated in the genome following Dnmt3a deletion. Both genetic and pharmacological inhibition of STING effectively slowed down the progression of hematopoietic disorders mediated by Dnmt3a deficiency, both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 7). When evaluating the potential of targeting STING to inhibit the proliferation of AML cells, the STING inhibitor exhibited effects comparable to an FDA-approved targeted drug for FLT3-ITD. This was observed in both the Dnmt3a-KO; FLT3-ITD mouse model and a human leukemia sample with the similar mutation background in a PDX model. Furthermore, the combined use of these two agents showed a cooperative effect, suggesting that targeting STING could be a strategy to enhance the clinical management of leukemia.

The mutated DNMT3A in HSCs leads to genome-wide hypomethylation. Beyond impacting gene regulation, this also results in the upregulation of previously silenced ERVs due to the absence of cytosine methylation-associated transcriptional inhibition. The increased ERV RNA can be reverse-transcribed into cDNA, which in turn activates the STING pathway and induces chronic inflammation in DNMT3A-mutated HSCs. This STING-dependent autonomous inflammation leads to increased self-renewal and biased lineage differentiation in DNMT3A-mutated HSCs. Inhibition of STING mitigates these phenotypes and prevents the development of leukemia associated with DNMT3A mutations in mouse models.

Inflammation plays a crucial role in promoting the development of CH and the initiation of hematopoietic malignancies. In a mouse CH model with mutated Dnmt3a, microbial infection-induced IFNγ expression drove the expansion of Dnmt3a mutant CH [16]. Additionally, similar phenotypes were observed in cases of CH involving mutated TET2. Microbial signals can trigger the release of cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. These elevated environmental cytokines result in inflammation-induced toxicity to WT HSCs [32, 33], while Tet2-deficient clones exhibit enhanced resistance to the inflammatory environment, gaining a competitive advantage over WT clones. Despite short-term exposure to infection-induced acute inflammatory responses, the mutated HSCs largely remain in a state of homeostasis throughout the majority of their lifespan. This means that mutated clones are not consistently exposed to environments with high levels of inflammatory factors. Therefore, it raises an intriguing question: What is the driving force that promotes the development of CH in the absence of infections? One of the significant stressors associated with CH is aging [34]. One mechanism driving aging-related progression of CH is thought to be “inflammaging”, a term that describes a baseline increase in the production of pro-inflammatory factors such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-6 over time across various tissues and organs, including the hematopoietic system [35,36,37]. Additionally, metabolism also contributes to the homeostasis of the hematopoietic hierarchy. Increased blood glucose levels have been shown to drive leukemogenesis in mice with TET2 mutations, partly due to the expression of the antiapoptotic, long noncoding RNA Morrbid [38]. Furthermore, cohort analyses have revealed that individuals with unhealthy diets—characterized by high obesity rates, high cholesterol, and low vitamin intake—show a higher prevalence of CH compared to those with a balanced diet [39, 40]. One plausible explanation for these findings is the dietary intake of vitamin C, as various studies have demonstrated that vitamin C is crucial for maintaining HSC homeostasis and balanced lineage differentiation by regulating the stability of the epigenetic landscape [41,42,43,44].

The cGAS-STING pathway plays a crucial role in various physiological and pathological processes, including immune defense, tumorigenesis, DNA damage response, cellular senescence and so on. Recently, a study reported that ERVs can activate the STING pathway to enhance erythropoiesis under conditions such as pregnancy and serial bleeding [45]. This work provides compelling evidence supporting the role of ERV-induced STING activation in unique hematopoietic processes. However, the study did not address why ERVs are upregulated in the hematopoietic cells of pregnant or bleeding mice. Based on our data, Dnmt3a-deficient hematopoietic cells or treatment with hypomethylating agents can induce ERV expression. We hypothesize that when the hematopoietic system is under pressure to rapidly produce cells, the acceleration of proliferation leads to incomplete genomic methylation, which subsequently upregulates ERV expression and activates the STING pathway. This low-grade inflammatory response may create a positive feedback loop that further promotes hematopoiesis in these unique contexts. Further studies are required to gain a deeper understanding of the role of STING in various hematopoietic contexts and to validate the underlying mechanisms.

Mutations in DNMT3A and TET2 account for nearly 70% of all genetic mutation events in CH [4,5,6]. As DNA cytosine-modifying enzymes, mutations in these two proteins exhibit highly similar phenotypes in HSC maintenance and skewed lineage differentiation. Therefore, researchers have spent over a decade identifying the shared mechanisms in hematopoietic disorders mediated by these two mutated enzymes. For example, one work reported that DNMT3A and TET2 both contributed to 5hmC maintenance [13]. According to this study, DNMT3A and TET2 collaborate to suppress the expression of Klf1, a transcription factor specific to the erythropoietic lineage, in HSCs. Sequencing analysis revealed that Klf1 gains 5hmC in DNMT3A-deficient HSCs and loses 5hmC at the transcription start site (TSS) when TET2 is absent. Another cohort study found that individuals with mutations in DNMT3A or TET2 acquired additional mutations at a higher rate, with odds ratios of 1.404 and 1.0937, respectively [46]. This suggests that loss of function mutations in these two genes increase the chance that HSCs acquire additional genetic lesions. Another study reported that deficiencies in DNMT3A or TET2 in the macrophages isolated from human atherosclerotic plaques led to activation of the cGAS-STING pathway, triggered by the release of mtDNA [24]. This finding suggested that the STING pathway might be a commonly affected pathway in hematopoietic cells with mutations of DNMT3A or TET2. Recently, our group identified that CH harboring TET2 mutations have a DNA damage-activated cGAS-STING pathway, which in turn stimulates a chronic inflammatory response and promotes the pathogenesis of CH in a non-infectious context [20]. Including data from our previous research, we demonstrated here that hematopoietic disorders associated with mutations in DNMT3A or TET2 both rely on the activated STING pathway to create a chronic inflammatory environment, which promotes the clonal expansion of mutated HSPCs. Our findings suggest that targeting STING could be a highly effective strategy to prevent or delay the progression to AML of CH-associated with mutations in DNA-modifying enzymes. More broadly, the concept of dampening inflammatory processes in the bone marrow might also be applicable to delay the progression of other preleukemic states like MDS and MPN.

Methods

Mouse models

Dnmt3af/f mice were generated as previously described [2]. The source of Sting-KO, Mx1-Cre and Vav-Cre mice were described in ref. [20]. Dnmt3af/f, Mx1-Cre and Sting-KO mice were crossed to produce Dnmt3af/f Mx1-Cre and Dnmt3af/f Mx1-Cre Sting-KO mice. To induce Dnmt3a conditional knock-out, the Mx1-Cre transgene was induced in 4-week-old mice using poly(I:C) at 250 μg/body administered intraperitoneally every other day for 8 times. All mice were bred on a C57BL/6 genetic background. CD45.1 recipient mice (B6.SJL) were kindly provided by Prof. Xiaolong Liu. Immuno-deficient (M-NSG) mice were obtained from Shanghai Model Organisms Center (NM-NSG-001) and used for establishing AML PDX models.

Bisulfite PCR sequencing

Genomic DNA (500 ng) was treated with EZ DNA methylation kit (D5001, Zymo). Bisulfite-treated DNA was amplified with gene-specific primers using Taq polymerse (T201, EnzyArtisan). PCR primers were listed in the Supplementary Table 1. PCR products were cloned into T vector (C601, Vazyme), transformed into DH5α and sequenced.

RNA-seq library preparation

About 300 hematopoietic cells per group were sorted directly into Smart-seq2 lysis buffer by FACS. Sorted cells were lysed and the reverse-transcribed RNA was amplified to obtain enough cDNA by a modified SMART-Seq2 protocol. cDNA was quantified by Qubit 3 (Q33327, Invitrogen), and 5 ng cDNA was used for cDNA library construction with TruePrep DNA Library Prep Kit V2 for Illumina (TD502, Vazyme).

RNA data processing

Raw data were trimmed by Trim Galore (v0.6.7) with default setting. The clean data were mapped to mm10 reference genome using Hisat2 (v7.5.0) in paired-end mode with default parameters. Gene count matrices were calculated by featureCounts (v2.0.1) with parameters -M -O. DEG analysis was performed by using DESeq2 (v1.34.0) package. Only genes with at least a twofold change and an adjusted P value less than 0.05 were considered to be differentially expressed. GO (Gene ontology) and KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway enrichment analyses were performed by using clusterProfiler (v4.10.0) package. To assess the transcription level of TE, TE transcripts (v.2.2.3) was applied to count TE and gene with the parameter mode multi. Differentially expressed TE analysis was performed by using DESeq2 package. Only TE with at least a 2-fold change and an P value less than 0.05 were considered to be differentially expressed.

WGBS data processing

Raw data were trimmed by Trim Galore (v0.6.7) with default setting. The clean data were mapped to mm10 reference genome using bismark (v0.23.1) in paired-end mode. PCR deduplicates were removed using deduplicate function of bismark. All replicates were merged for further analysis. Then, the methylation levels of CpG sites were quantified using extractor function of bismark. Bigwig files were generated using bedGraphToBigWig (v.4) and visualized in Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV). The annotation files of genes and repetitive elements (RepeatMasker) were downloaded from the UCSC Genome Browser. The methylation levels of different genomic elements were calculated with bedtools (v2.30.0). Metaplots for 5mC and 5hmC levels were generated using deepTools (v3.5.5).

Additional methods including bone marrow transplantation, FACS analysis, LC-MS etc. are presented in Supplementary Data.

Responses