Stressors affect human motor timing during spaceflight

Introduction

Crewed lunar or even Martian missions are imminent in the coming decades, and human operational performance during spaceflight requires adequate motor capacity in the face of radical environmental changes. However, sensorimotor performance deteriorates during spaceflight, especially in its initial phase1. Experimental work also revealed impaired motor control in spaceflight, with various motor tasks including manual tracking, hand aiming and pointing, eye-hand coordination, and postural control2. Two categories of contributing factors for motor changes have been proposed3. The first category is the direct effect of microgravity on the sensorimotor system, including reduced spinal excitability4, inappropriate internal representations of gravity5, modified motor strategy6,7, reduced cognitive resources for motor control due to sensorimotor adaptation to weightlessness3, sensory disturbances in modalities like vestibular sense8, proprioception9,10, and vision3,11. The second category concerns the cognitive effects of non-specific stressors in the challenging work environment during spaceflight, including high workload, sleep loss, fatigue, confinement, disturbed circadian rhythms, and social isolation1.

However, the evidence for the negative impact of non-specific stressors, assumed via cognitive functions, on sensorimotor performance remains elusive. There is no substantial evidence that cognitive functions are impaired during spaceflight: despite anecdotal reports about space fog or space dementia12, standard cognitive tests failed to find consistent cognitive or attentional deficits13. The evidence supporting the role of non-specific stressors is primarily from experiments on cognitive-motor dual tasks14,15,16,17,18. For instance, when people track visual targets by hand, a simultaneous cognitive task, e.g., a memory search of memorized items or a fast reaction to visual stimuli, would have a detrimental effect on manual tracking15,17. This dual-task performance decrement is significantly larger during spaceflight than on the ground and sometimes co-occurs with astronauts’ heightened perceived stress and workload17,19. As the impairment in manual tracking is not changed by task difficulty of the cognitive task, some researchers attributed it to affected attention switching caused by non-specific stressors14,17,20,21.

However, even the performance of the single task of manual tracking deteriorates during spaceflight relative to the pre-flight baseline15,18,22. Furthermore, some studies reported that the dual-task deficit disappeared when the motor task or the concurrent cognitive task was easy15,16. These findings suggest that the dual-task deficit might reflect a scarcity of neural resources that are occupied by sensorimotor adaptation to the space environment15. This means that it can be attributed to, at least partially, adaptive changes in sensorimotor systems to microgravity3,15, as opposed to the cognitive effect of non-specific stressors.

Furthermore, impaired proprioception, caused by altered muscle spindle activity in weightlessness23, affects movement control, including manual tracking10. Thus, the dual-task effect, typically quantified by manual tracking performance, might be caused by the direct effect of microgravity on proprioception, as opposed to by non-specific stressors.

To demonstrate the effect of nonspecific stressors, we started off our study by minimizing the direct effect of microgravity on the sensorimotor system. We opted to use a motor timing production task24, without a dual task, to evaluate the central control of movements during prolonged missions in the China Space Station (CSS). This task is minimalistic in motor execution: the participants simply tap their finger on a key in synchronization with a metronome and then continue at the same pace without the metronome. Common microgravity-related motor disturbances, including postural control25, eye-hand coordination26, hand trajectory control27,28,29, and manual tracking15,18, are avoided in our task. Similarly, our task also minimally relies on sensory feedback since people spontaneously tap according to the memorized tempo during the continuation part. Common microgravity-related sensory disturbances, including visual30,31, vestibular8, and force sensations32 are thus avoided. In particular, the influence of microgravity-induced proprioceptive disturbance33 is also minimized since our task has no requirement for trajectory control. More importantly, the synchronization-continuation paradigm enables a model-based analysis to reliably decompose the timing variability into a motor noise component tied to movement execution and a central noise component tied to action planning24,34,35. This decomposition has been shown to reliably delineate the functional role of central versus peripheral neural substrates underlying motor control. For instance, peripheral neuropathies selectively impair the motor noise component, while neuropathies in various brain regions (e.g., cerebellum or frontal cortices) impair central and motor noise components in a lesion-specific way36,37. We thus hypothesize that nonspecific stressors during spaceflight, if at work, would selectively impair the central noise and spare the motor noise.

Two previous studies with limited numbers of participants (n = 2 and 3) used the synchronization-continuation paradigm to probe motor timing during spaceflight38,39. Though a trend of increasing timing variance had been identified, no conclusion could be reached due to inconsistent findings between the two studies and limited sample size. The limited sample size in space research made resolving theoretical controversies difficult. The aforementioned dual-task studies had participants <5, sometimes even a single participant7,14,15,16,17,18,20,22,26,39,40,41, while substantial inter-individual differences in sensorimotor performance are widely recognized. We recruited all twelve taikonauts from CSS in its very first four missions to perform the synchronization-continuation experiment. We also recruited an age- and gender-matched ground control group to address the confounding practice effect inherent in repetitive testing of the same task.

Results

The taikonauts performed the task before (2 sessions), during (2–3 sessions), and after (2 sessions) 3–6 months of spaceflight (Fig. 1A, B and Table 1). Every session included three target periods of 360 ms, 460 ms, and 610 ms, each repeated for six trials. The participants started a trial by tapping on the space key to synchronize with the period-setting metronome for 20 times. They continued tapping with the same tempo without the metronome for another 30 times. The performance in the continuation part reflects the ability of motor timing control and is the main focus of our study. Pooled over sessions, data were organized into three phases corresponding to pre-, in-, and post-spaceflight (Fig. 1C).

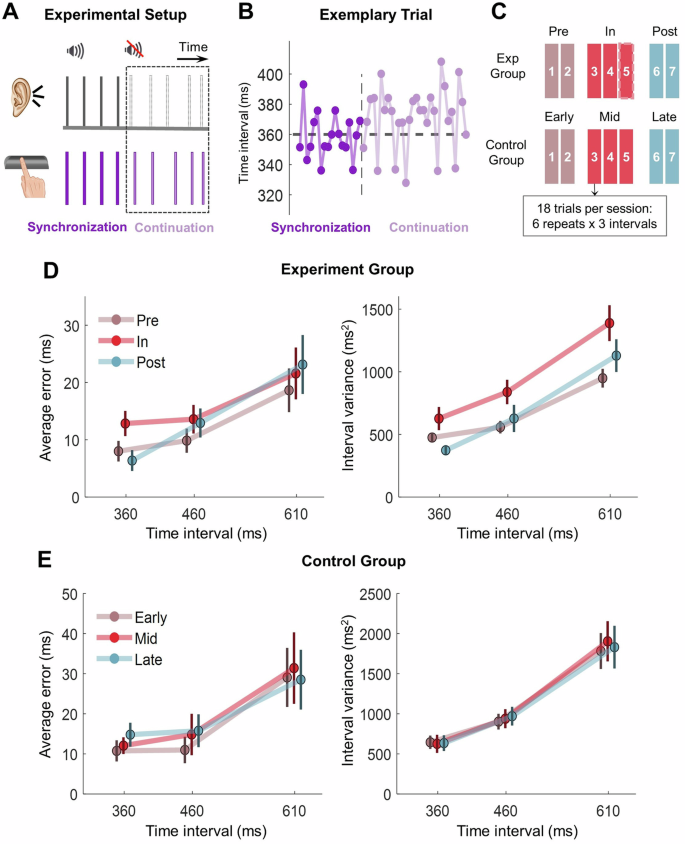

A Procedures in a trial. In the first synchronization part, the participants followed an auditory metronome by tapping their index finger on the space key. They kept tapping at the same pace after the auditory pacing was withdrawn in the continuation part. B Tapping intervals in a typical trial with a target period of 360 ms from an exemplary participant in the experimental group, plotted as a function of the tap number. C Session schedules of the task. For the experimental group, there are 2, 3, and 2 sessions in pre-, in-, and post-flight phases, respectively. The dashed outer box means only a subgroup of participants performed this session (see Methods and Table 1). To match the number of phases between groups, the test sessions of the control groups were also divided into three phases, which included 2, 3 and 2 sessions, respectively. D Average timing error and timing variance of the experimental group. The x-axis is the target period, and circles and error bars indicate mean and standard error rates among individuals. E Same as D for the control group.

Spaceflight increases timing variance but spares the average timing error

We found that the taikonauts accurately produced the required tapping interval with and without the metronome, independent of the testing phase (Supplementary Results 1, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Fig. 1D, left panel). For the critical continuation part, the average timing error was around 10 ~ 20 ms, depending on the target period (Fig. 1D, left panel). Repeated-measures ANOVA showed that the average error increased with target period (F(2,40) = 7.577, p = 0.015) but was not affected by phase (main effect of phase: F(2,40) = 1.304, p = 0.292; interaction: F(4,40) = 0.946, p = 0.412).

However, spaceflight increased the timing variance of tapping intervals during the continuation part (Fig. 1E). The variance increased with the target period (F(2,40) = 74.945, p < 0.001) and, importantly, differed between phases (F(2,40) = 10.164, p = 0.002) without an interaction effect (F(4,40) = 1.686, p = 0.193). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed that variance during the in-flight phase was significantly higher than the pre-flight (p = 0.018) and post-flight phase (p = 0.006). This hike in timing variance was not accompanied by increased sleepiness (Karolinska Sleepiness Scale, KSS; see Supplementary Results 4 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

To examine possible adaptive changes during early flight, we compared the performance of the first and second sessions in the in-flight phase (sessions 3 and 4). We found the same main effect of target period (F(2,20) = 22.068, p < 0.001) but no significant effect of session or interaction (all p > 0.16; Supplementary Results 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Thus, we did not find evidence for an adaptive change in motor timing for the duration examined (20 days to 116 days in space).

Our age- and gender-matched ground control group was tested with the same number of sessions and trials, with a similar spacing between sessions (Fig. 1C, lower panel). Both average timing error and timing variance showed a significant effect of target period (average timing error: F (2.20) = 5.765, p = 0.031; timing variance: F (2,20) = 29.733, p < 0.001), but no main effect of phase or interaction was found (Fig. 1E). Thus, using repetitive testing to explain away the phase effect in the experimental group was not supported.

Though not our study focus, the synchronization part showed that neither average timing error nor timing variance was affected by spaceflight (Supplementary Results 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). The average timing error was as small as <5 ms during synchronization, suggesting that all participants performed well with metronome pacing.

In sum, spaceflight selectively increases the variance of motor timing but spares the average timing error. This increase in motor timing variability was specifically in the continuation phase when the taikonauts were required to spontaneously produce certain timing intervals without the metronome pacing.

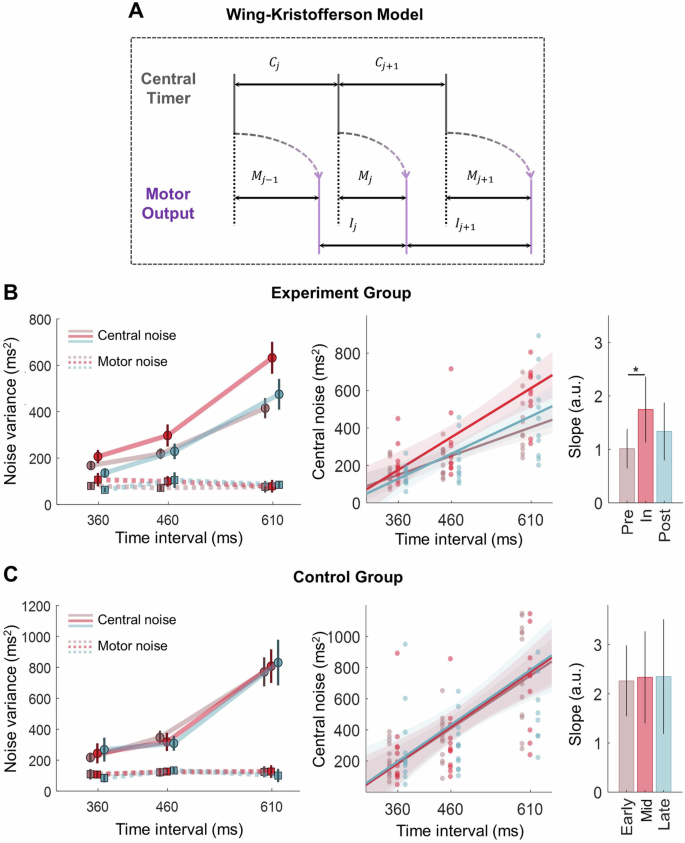

The increase in timing variance was further investigated by using the Wing-Kristofferson model, which decomposed the timing variance into a central noise and a motor noise (Fig. 2A24;). As expected42,43, central noise increased with the target period (F(2,40) = 36.404, p < 0.001; Fig. 2B). Importantly, the main effect of phase was highly significant (F(2,40) = 9.403, p = 0.002). The interaction was only marginally significant (F (4,40) = 3.057, p = 0.051). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons showed that the in-flight phase had significantly higher central noise than the pre- and post-flight phases (p = 0.019 and p = 0.005, respectively). In contrast, motor noise was not modulated by target period or phase (two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, all p > 0.3; Fig. 2B). While the null effect of the target period was expected42,44, the lack of phase effect indicated that spaceflight did not affect the motor execution noise, in line with our hypothesis.

A Illustration of Wing-Kristofferson model24. The tapping time (purple solid line) is jointly determined by the timing signal of the hypothetical central timer (C) and the motor delay (M) inherent in motor execution. The former is subject to central noise while the latter to motor noise. B The decomposed noise variance and slope analysis in the experimental group. Left panel: the estimated central and motor noise variance as a function of target period. Error bars indicate mean and standard error among individuals. Solid and dashed lines represent the central and motor noises, respectively. Middle panel: linear regression analysis with target period as the predictor and central noise as the dependent variable, colors denote different phases. Each dot represents the estimated central noise for an individual in a specific phase and target period. The shading area is the 95% confidence interval of prediction. Right panel: The slope of linear regression. Bars and error bars represent slope and 95% confidence interval at each phase. * denotes p < 0.05 for pairwise comparison (see details in Supplementary Materials). C Same as B for the control group.

Previous studies suggest that the central noise increases linearly with the target period, and the slope is larger when people are less task-engaging for this timing task43. Thus, the linear dependency can be viewed as a proxy of cognitive engagement. We fitted the central noise (({sigma }_{c}^{2})) with a linear model:(,{sigma }_{c}^{2}={kT}+c), where T is the target period (Fig. 2B). Results showed the slope k was significantly larger in the in-flight phase than in the pre-flight phase (Z = −0.208, p = 0.038), while the intercept c did not differ between phases (all p > 0.16).

Notably, the phase effects for central noise were absent in the control group (Fig. 2C). Though their central noise but not the motor noise increased with target period (F(2,22) = 40.096, p < 0.001), both central and motor noise failed to change as a function of phase (all p > 0.5). The slope and intercept obtained from slope analysis did not show any difference across phases either (all p > 0.9, Appendix 3). Thus, the spaceflight selectively increased the central noise and its linear dependency on period among the taikonauts.

Discussion

Our study provides converging evidence to support the significant role of nonspecific stressors on sensorimotor performance during prolonged spaceflight. Using the simple, spontaneous finger-tapping task, we minimized the effect of microgravity on the sensory and motor system and isolated the disturbing effect of nonspecific stressors in the space station. Indeed, the variance in action timing, reflecting the noise in motor execution, remained unchanged by spaceflight. The substantial increase in timing variance is largely driven by central noise, reflecting an inflated noise in action planning. This finding is further corroborated by the increase in linear dependency of central noise on the tapping period, which reflects an increase in cognitive engagement during spaceflight. These substantial effects, initially observed 4 weeks after launch, did not show any sign of improvement and only returned to the pre-launch baseline 4 weeks after landing. In contrast, the ground control group did not show any longitudinal changes, supporting that the inflated central noise is spaceflight-specific. Our findings suggest that during prolonged spaceflight, people’s sensorimotor performance is negatively affected by nonspecific stressors, in addition to the well-established direct effect of microgravity.

Our experimental task minimized the impact of various sensory disturbances in microgravity, including proprioceptive, vestibular, and visual disturbances2,30,33,45. The simple finger tapping does not require fine control of movement kinematics, minimizing the role of proprioceptive control, and it is internally driven by a memorized auditory pacing44, minimizing the role of visual and vestibular control. Similarly, typical spaceflight-related changes in motor execution do not affect our simple tapping task. For example, due to weightlessness, spinal excitability reduces dramatically, which can affect spinal reflexes4 and voluntary movement control46. Furthermore, body-weight unloading leads to an underestimation of body mass, contributing to movement slowing47,48. However, these direct effects of microgravity on motor execution should not impact the tiny movement of a low-mass finger. Indeed, besides an unchanged average timing error, we found that model-derived motor noise remains unchanged during spaceflight, suggesting motor execution of the finger tapping is intact24,34,35. The increase in timing variance is largely driven by a surge in central noise, highlighting the effect of nonspecific stressors on the central control of actions.

The observed inflated central noise is significant since central noise is robust against cognitive declines such as those from aging49,50 and even mild dementia of the Alzheimer type51. Neurological patients with Parkinson’s disease, cerebellar lesions, or stroke show an increase in central noise37,52, but their timing deficits are expected since they have lesions in the key brain regions underlying timing processing and production, including the basal ganglia and the cerebellum53,54,55. Then, why did astronauts, without brain trauma, exhibit a substantial increase in central noise, after prolonged exposure to microgravity? We postulate that non-specific stressors in microgravity affect people’s attention function14,56,57, which in turn deteriorates the unpaced tapping in the continuation phase that demands sustained attention. Our postulation is corroborated by the fact that adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) also selectively increase their central noise in the synchronization-continuation paradigm58. Furthermore, the timing performance from the synchronization-continuation paradigm in healthy participants has been shown dependent on top-down control from the prefrontal cortex to the motor and sensory regions59, suggesting that attention control is critical for this task.

We expect the nonspecific stressors to have a broad impact on sensorimotor control during spaceflight beyond our motor timing task, but their influence should be task-dependent. In fact, motor timing with auditory pacing, as in the synchronization phase of our task, is not affected during spaceflight, hinting that action control with online feedback is intact. This is in line with the previous postulation that performance decrement caused by attentional abnormalities under microgravity is limited to feedforward-controlled actions16,60,61. Nonspecific stressors affect people’s attention and cognitive resources, which are demanded differently in various tasks. Our motor timing task is selectively impaired during the continuation part when sustained attention and working memory are demanded: the participants need to accurately memorize the metronome-specified tempo and sustain their attention without auditory pacing for 10.8 to 18.3 seconds, contingent on individual performance and target period. Recently, Tays and colleagues reported a rare case where the dual-task decrements in spaceflight were absent62, in stark contrast to previous findings14,15,16,18,56. Arguably, the dual tasks they used were relatively easy, with a two-alternative RT task as the motor task and an oddball detection task as the cognitive task. Previous studies, instead, used unstable tracking as the motor task and memory search as the cognitive task15,56. Thus, the absence of the dual-task decrement hints that nonspecific stressors would affect sensorimotor performance only when the tasks are demanding for cognitive resources. This postulation is also in line with previous findings that task difficulty, manipulated by varying cognitive overloading, increases the dual-task decrement15,16. In this light, nonspecific stressors possibly limit available cognitive resources for sensorimotor control, thus impairing motor performance when the task is attention-demanding (as in our finger-tapping task) and difficult15,16.

Our findings on motor timing also have implications for temporal perception during spaceflight. Anecdotal reports show that the perceived time intervals are compressed than actual ones in orbit, a so-called “time compression syndrome”63. A recent observational study returned intriguing findings: compared to the pre-flight, astronauts underestimated the event intervals of hours and overestimated 1 min, but they accurately estimated the intervals in the number of days (e.g., the duration from the last spacewalk)64. These nuanced perceptual changes have been attributed to nonspecific stressors, sensory disturbances (reduced vestibular simulations), and motor changes (slow motions) during the flight64. Our study highlights that fine-grained task design and analysis are needed to tease apart these contributing factors.

Two earlier studies employed the same synchronization-continuation tapping paradigm to investigate motor control under microgravity, though their focus was on motor timing as opposed to the effect of non-specific stressors (Semjen et al. 1998; Semjen et al. 1998). These studies involved only 2–3 participants, and the individual participants differed in inter-tap intervals and motor noise. However, these studies found an increasing tendency for central noise, which inspired us to use the synchronization-continuation paradigm. Our study benefits from a larger sample size as well as some methodological improvements over these two relevant studies: more tapping data from multiple sessions, data detrending to remove possible drift of tapping period, and uneven spacing of tapping period to critically test the linear relationship between period and noise measures. One limitation of our study is that no data was collected early in the flight (e.g., the first week after launch) due to critical onboard duties. However, we expect the effect size of central noise to be even larger than what we reported here since the early flight is a critical adaptive phase with severe challenges in subjective mood and well-being1.

Separating the contribution from the direct effect of microgravity and the effect of nonspecific stressors has important implications for future space missions16. Our study highlights those nonspecific stressors during spaceflight negatively impact sensorimotor performance, likely via attentional changes and cognitive overloading, and thus suggests that pre-flight training on coping with the challenging working environment is necessary for maintaining sensorimotor capacity during manned space missions.

Methods

Space experiment

Participants. Twelve taikonauts from the first four CSS missions were recruited for the experiment, eleven of them (2 females, 9 males, 49.0 ± 6.5 years old) finished the tasks, and one of them quit in the in-flight phase due to time conflict. They were all right-handed and provided a written informed consent form approved by the Ethics Committee of the China Astronaut Research and Training Center and the Institutional Review Board of Peking University. The participants were exposed to microgravity for 92–187 days during the manned flight missions of China’s Shenzhou Program (Mission 12 – 15). Due to operational and mission constraints, the time schedule of the experiments differed across participants, as shown in Table 1. Five participants performed 6 sessions, and the other six participants performed one additional in-flight session. Experiments were performed mostly during the usual working hours, the exact hours for each participant are detailed in Supplementary Table 2.

Task and experimental design. The task was performed with a PC, a pair of noise-canceling earphones, and a wired keyboard. The earphones and keyboard were connected to the tablet via a USB connector. In the in-flight sessions, the participants wore the earphones and “stood” in a neutral posture with both feet constrained by foot straps in front of a foldable tabletop 0.9 meters high from the cabin floor. While performing the task, they used their left hand to hold the edge of the table, leaving their right hand free to press the keyboard. The foot straps and a left hand grip provides sufficient stabilization for possible disturbances from finger taps on the keyboard.The tablet was attached by velcro to the tabletop about 35 cm in front and 30 cm below the participant’s chest level. The keyboard was laid flat attached with velcro on the same tabletop, while the tablet screen was slant-placed to provide visual guidance and feedback to the participants. In each session, participants did the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale (KSS) test65 as measures of fatigue by rating their sleepiness from “very sleepy” (10 point) to “very alert” (1 point) (see more details in Appendix 4). Before the experiment started, participants put their index finger above the space key and wait for the initiation. A customized software implemented on the tablet is used to display instructions, deliver visual and auditory stimuli, and register keypresses.

At the beginning of each trial, a series of 50-ms metronome beeps were played by the tablet with a fixed inter-beep target period. After listening to the beeps 3-5 times via the earphones, the participants tapped the space key with their dominant index finger at the same time as the metronome beep. After 20 successive taps in this synchronization part, the metronome discontinued, and the participants were required to continue tapping at the same pace in the continuation part. The continuation part of each trial terminated after 30 self-paced taps. The average tapping interval error during the continuation part would be calculated by the software and presented to the participants at the end of each trial to encourage them to perform with timing accuracy and precision. Three target periods, i.e., 360, 460, and 610 ms, were repeated for 6 trials in each experimental session. All trials were presented in a random order. We chose 3 target intervals that around human’s preferred inter-tap interval (500 ms; Repp, 2005). The uneven spacing of the target periods to better detect a possible non-linear relationship between noise and period. Each trial lasted ~18–30 s. Subjects were self-paced between trials: the next trial would begin only after they felt ready and pressed the spacebar. We found the inter-trial interval has a range of 14.92 ± 10.74 s. As a result, each session lasted around 11–12 min in total.

Ground-based control experiment

Participants. Twelve participants (2 females, 10 males, 49.9 ± 6.5 years old) were recruited from the residents of Beijing. All of them had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, right-handed, and had no known neuromotor disorders. They were provided with a written informed consent form approved by the Institutional Review Board of Peking University and received monetary compensation for their participation. All sessions of the control experiment were conducted on the campus of Peking University.

Task and experimental design. The aim of the control experiment is to evaluate the longitudinal changes in motor timing performance when the same synchronization-continuation task is performed repetitively. Our control participants performed the same finger-tapping task with the exact copies of devices and software programs as the experimental group for seven sessions under normal gravity. The layout of the table and the tablet was also similarly arranged as the experimental group, except that the participants were seated in front of the table. The time between two successive data collection sessions was 6–9 days.

Data analysis

Pre-processing. The inter-tap intervals (ITI) were computed as the time differences between two adjacent taps. For each trial, ITIs below and over 2.5 times of Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) of the current trial were regarded as outliers and removed. In total, there are 4.34% ± 0.68% (mean ± std between participants) of the taps identified as outliers and removed from the experimental group, 2.79% ± 1.16% of taps were removed from the control group. To eliminate the possible transient effect from synchronization to continuation, we further excluded the first 5 taps of continuation in each trial. In each test phase, the average timing error ({e}_{{ave}}) was calculated as: ({e}_{{ave}}=frac{{sum }_{i}|{I}_{i}-{D|}}{N}), where I is the ITI between taps, D is the target period of the current trial, N is the total number of valid taps (Fig. 1D, E, left panel), and the timing variance was determined as the variance of ITIs (Fig. 1D, E, right panel).

Wing-Kristofferson model. Following the Wing-Kristofferson decomposition model (Fig. 1A), the tapping interval at the j-th tap in a trial can be denoted as: ({I}_{j}={C}_{j}+{M}_{j}-{M}_{j-1}), where I is the ITI between two taps, C corresponds to the interval of the central timer and M is the time delay of the motor system. Both M and C are assumed to follow stationary normal distributions. The model has two additional assumptions: i) M and C are independent of each other, and ii) the time series of M and C are independent within the system. Thus, the variance of I is ({sigma }_{I}^{2}={sigma }_{c}^{2}+{2sigma }_{M}^{2}), and the lag-1 autocorrelation is ({rho }_{1}=-frac{{sigma }_{M}^{2}}{{sigma }_{c}^{2}+2{sigma }_{M}^{2}}). From the above equations, we can estimate the variance of M and C as: ({sigma }_{M}^{2}=-{sigma }_{I}^{2}{rho }_{1}), ({sigma }_{c}^{2}={sigma }_{I}^{2}-2{sigma }_{M}^{2}). As the drift of ITI away from the target period would inflate the variance estimate, we detrended the filtered ITIs in the continuation phase using a linear function. Furthermore, short time series would bias parameter estimation and reduce the reliability of model-based analysis34. Thus, data from multiple test sessions in the pre-flight (Session 1-2), in-flight (Session 3-5) and post-flight (Session 6-7) phases were pooled for the experimental group before the decomposition analysis. Similarly, data from Session 1-2, 3-5 and 6-7 were pooled for the control group (Fig. 1C).

Statistical analysis. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs are conducted on average timing error, timing variance, motor noise variance, and central noise variance with a 3 (phase) x 3 (target period) design. Greenhouse-Geisser corrections were applied when the assumption of sphericity was violated66. Tukey’s HSD tests were used for post hoc pairwise comparisons. For every dependent measure, we conducted Shapiro-Wilk tests for each of the 9 levels (3 periods × 3 phases) to test the normality assumption. In the experimental group, 77.78% of the tests met the normality assumption, 22.22% tests had mild violations (p > 0.01). Given that repeated-measures ANOVA (rm-ANOVA) is typically robust to mild violations of normality, especially with equal sample sizes and non-severe deviations (Wilcox 2014), we reported the results of rm-ANOVA in the main text. However, we also used the Aligned Rank Transform (ART) procedure, a non-parametric method, to re-examine all the effects. The results from the ART analysis replicates all the findings from standard rm-ANOVA, and its detailed results can be found in Supplementary Table 3.

Linear regressions assessed the dependency of the central noise on target period: ({sigma }_{c}^{2}={kD}+c), where D is the target period, ({sigma }_{c}^{2}) was the variance of central noise estimated from the experimental data, and k and c were the regression coefficients denoted as slope and intercept. To test the difference in regression coefficients between test phases, we used the method suggested by ref. 67. The slope k was compared between conditions by using Z-scores: (Z=frac{{b}_{1}-{b}_{2}}{sqrt{{SE}{b}_{1}^{2}+{SE}{b}_{2}^{2}}}), where ({b}_{1}) and ({b}_{2}) are the mean of two groups, ({SE}{b}_{1}^{2}) and ({SE}{b}_{2}^{2}) are the coefficient variances of the corresponding conditions. The Z-scores were then converted to p-values based on a two-tailed hypothesis.

Responses